Italy

Italy (Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja] (![]()

Italian Republic | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms

| |

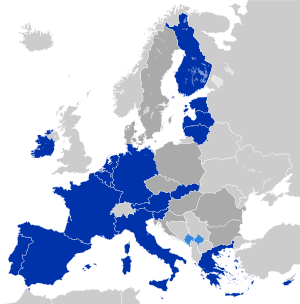

.svg.png)  Location of Italy (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Rome 41°54′N 12°29′E |

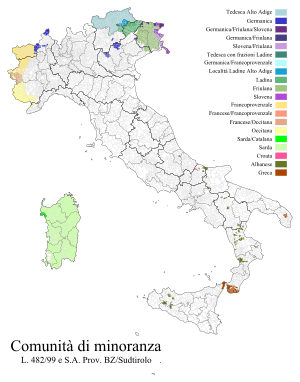

| Official languages | Italiana |

| Native languages | See full list |

| Ethnic groups (2017)[1] |

|

| Religion (2015)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Italian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Sergio Mattarella | |

| Giuseppe Conte | |

| Elisabetta Casellati | |

| Roberto Fico | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate of the Republic | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Formation | |

| 17 March 1861 | |

• Republic | 2 June 1946 |

| 1 January 1948 | |

| 1 January 1958 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 301,340 km2 (116,350 sq mi) (71st) |

• Water (%) | 2.4 |

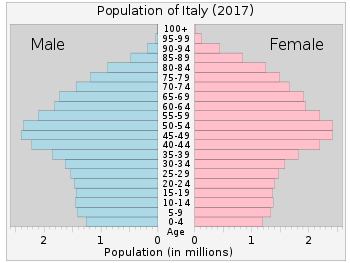

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | |

• 2011 census | |

• Density | 201.3/km2 (521.4/sq mi) (63rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 29th |

| Currency | Euro (€)b (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy yyyy-mm-dd (AD)[8] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +39c |

| ISO 3166 code | IT |

| Internet TLD | .itd |

| |

Due to its central geographic location in Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, Italy has historically been home to myriad peoples and cultures. In addition to the various ancient peoples dispersed throughout what is now modern-day Italy, the most predominant being the Indo-European Italic peoples who gave the peninsula its name, beginning from the classical era, Phoenicians and Carthaginians founded colonies mostly in insular Italy,[19] Greeks established settlements in the so-called Magna Graecia of Southern Italy, while Etruscans and Celts inhabited central and northern Italy respectively. An Italic tribe known as the Latins formed the Roman Kingdom in the 8th century BC, which eventually became a republic with a government of the Senate and the People. The Roman Republic initially conquered and assimilated its neighbours on the Italian peninsula, eventually expanding and conquering parts of Europe, North Africa and Asia. By the first century BC, the Roman Empire emerged as the dominant power in the Mediterranean Basin and became a leading cultural, political and religious centre, inaugurating the Pax Romana, a period of more than 200 years during which Italy's law, technology, economy, art, and literature developed.[20][21] Italy remained the homeland of the Romans and the metropole of the empire, whose legacy can also be observed in the global distribution of culture, governments, Christianity and the Latin script.

During the Early Middle Ages, Italy endured the fall of the Western Roman Empire and barbarian invasions, but by the 11th century numerous rival city-states and maritime republics, mainly in the northern and central regions of Italy, rose to great prosperity through trade, commerce and banking, laying the groundwork for modern capitalism.[22] These mostly independent statelets served as Europe's main trading hubs with Asia and the Near East, often enjoying a greater degree of democracy than the larger feudal monarchies that were consolidating throughout Europe; however, part of central Italy was under the control of the theocratic Papal States, while Southern Italy remained largely feudal until the 19th century, partially as a result of a succession of Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Angevin, Aragonese and other foreign conquests of the region.[23] The Renaissance began in Italy and spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration and art. Italian culture flourished, producing famous scholars, artists and polymaths. During the Middle Ages, Italian explorers discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. Nevertheless, Italy's commercial and political power significantly waned with the opening of trade routes that bypassed the Mediterranean.[24] Centuries of rivalry and infighting between the Italian city-states, such as the Italian Wars of the 15th and 16th centuries, left Italy fragmented and several Italian states were conquered and further divided by multiple European powers over the centuries.

By the mid-19th century, rising Italian nationalism and calls for independence from foreign control led to a period of revolutionary political upheaval. After centuries of foreign domination and political division, Italy was almost entirely unified in 1861, establishing the Kingdom of Italy as a great power.[25] From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Italy rapidly industrialised, mainly in the north, and acquired a colonial empire,[26] while the south remained largely impoverished and excluded from industrialisation, fuelling a large and influential diaspora.[27] Despite being one of the four main allied powers in World War I, Italy entered a period of economic crisis and social turmoil, leading to the rise of the Italian fascist dictatorship in 1922. Participation in World War II on the Axis side ended in military defeat, economic destruction and the Italian Civil War. Following the liberation of Italy the country abolished their monarchy, established a democratic Republic and enjoyed a prolonged economic boom, becoming a highly developed country.[28]

Today, Italy is considered to be one of the world's most culturally and economically advanced countries,[28][29][30] with the world's eighth-largest economy by nominal GDP (third in the European Union), sixth-largest national wealth and third-largest central bank gold reserve. It ranks very highly in life expectancy, quality of life,[31] healthcare,[32] and education. The country plays a prominent role in regional and global economic, military, cultural and diplomatic affairs; it is both a regional power[33][34] and a great power,[35][36] and is ranked the world's eighth most-powerful military. Italy is a founding and leading member of the European Union and a member of numerous international institutions, including the UN, NATO, the OECD, the OSCE, the WTO, the G7, the G20, the Union for the Mediterranean, the Council of Europe, Uniting for Consensus, the Schengen Area and many more. The country has long been a global centre of art, music, literature, philosophy, science and technology, and fashion, and has greatly influenced and contributed to diverse fields including cinema, cuisine, sports, jurisprudence, banking and business.[37] As a reflection of its cultural wealth, Italy is home to the world's largest number of World Heritage Sites (55), and is the fifth-most visited country.

Name

Hypotheses for the etymology of the name "Italia" are numerous.[38] One is that it was borrowed via Greek from the Oscan Víteliú 'land of calves' (cf. Lat vitulus "calf", Umb vitlo "calf").[39] Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus states this account together with the legend that Italy was named after Italus,[40] mentioned also by Aristotle[41] and Thucydides.[42]

According to Antiochus of Syracuse, the term Italy was used by the Greeks to initially refer only to the southern portion of the Bruttium peninsula corresponding to the modern province of Reggio and part of the provinces of Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia in southern Italy. Nevertheless, by his time the larger concept of Oenotria and "Italy" had become synonymous and the name also applied to most of Lucania as well. According to Strabo's Geographica, before the expansion of the Roman Republic, the name was used by Greeks to indicate the land between the strait of Messina and the line connecting the gulf of Salerno and gulf of Taranto, corresponding roughly to the current region of Calabria. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name "Italia" to a larger region[43] In addition to the "Greek Italy" in the south, historians have suggested the existence of an "Etruscan Italy" covering variable areas of central Italy.[44]

The borders of Roman Italy, Italia, are better established. Cato's Origines, the first work of history composed in Latin, described Italy as the entire peninsula south of the Alps.[45] According to Cato and several Roman authors, the Alps formed the "walls of Italy".[46] In 264 BC, Roman Italy extended from the Arno and Rubicon rivers of the centre-north to the entire south. The northern area of Cisalpine Gaul was occupied by Rome in the 220s BC and became considered geographically and de facto part of Italy,[47] but remained politically and de jure separated. It was legally merged into the administrative unit of Italy in 42 BC by the triumvir Octavian as a ratification of Caesar's unpublished acts (Acta Caesaris).[48][49][50][51][52] The islands of Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily and Malta were added to Italy by Diocletian in 292 AD.[53]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Thousands of Paleolithic-era artifacts have been recovered from Monte Poggiolo and dated to around 850,000 years before the present, making them the oldest evidence of first hominins habitation in the peninsula.[55] Excavations throughout Italy revealed a Neanderthal presence dating back to the Palaeolithic period some 200,000 years ago,[56] while modern Humans appeared about 40,000 years ago at Riparo Mochi.[57] Archaeological sites from this period include Addaura cave, Altamura, Ceprano, and Gravina in Puglia.[58]

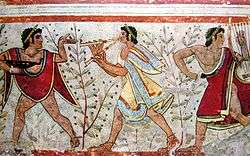

The Ancient peoples of pre-Roman Italy – such as the Umbrians, the Latins (from which the Romans emerged), Volsci, Oscans, Samnites, Sabines, the Celts, the Ligures, the Veneti, the Iapygians and many others – were Indo-European peoples, most of them specifically of the Italic group. The main historic peoples of possible non-Indo-European or pre-Indo-European heritage include the Etruscans of central and northern Italy, the Elymians and the Sicani in Sicily, and the prehistoric Sardinians, who gave birth to the Nuragic civilisation. Other ancient populations being of undetermined language families and of possible non-Indo-European origin include the Rhaetian people and Cammuni, known for their rock carvings in Valcamonica, the largest collections of prehistoric petroglyphs in the world.[59] A well-preserved natural mummy known as Ötzi the Iceman, determined to be 5,000 years old (between 3400 and 3100 BCE, Copper Age), was discovered in the Similaun glacier of South Tyrol in 1991.[60]

The first foreign colonizers were the Phoenicians, who initially established colonies and founded various emporiums on the coasts of Sicily and Sardinia. Some of these soon became small urban centres and were developed parallel to the Greek colonies; among the main centres there were the cities of Motya, Zyz (modern Palermo), Soluntum in Sicily and Nora, Sulci, and Tharros in Sardinia.[61]

Between the 17th and the 11th centuries BC Mycenaean Greeks established contacts with Italy[62][63][64][65] and in the 8th and 7th centuries BC a number of Greek colonies were established all along the coast of Sicily and the southern part of the Italian Peninsula, that became known as Magna Graecia. The Greek colonization placed the Italic peoples in contact with democratic government forms and with elevated artistic and cultural expressions.[66]

Ancient Rome

Rome, a settlement around a ford on the river Tiber in central Italy conventionally founded in 753 BC, was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. In 509 BC, the Romans expelled the last king from their city, favouring a government of the Senate and the People (SPQR) and establishing an oligarchic republic.

The Italian Peninsula, named Italia, was consolidated into a single entity during the Roman expansion and conquest of new lands at the expense of the other Italic tribes, Etruscans, Celts, and Greeks. A permanent association with most of the local tribes and cities was formed, and Rome began the conquest of Western Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East. In the wake of Julius Caesar's rise and death in the first century BC, Rome grew over the course of centuries into a massive empire stretching from Britain to the borders of Persia, and engulfing the whole Mediterranean basin, in which Greek and Roman and many other cultures merged into a unique civilisation. The long and triumphant reign of the first emperor, Augustus, began a golden age of peace and prosperity. Italy remained the metropole of the empire, and as the homeland of the Romans and the territory of the capital, maintained a special status which made it "not a province, but the Domina (ruler) of the provinces".[67] More than two centuries of stability followed, during which Italy was referred to as the rectrix mundi (queen of the world) and omnium terrarum parens (motherland of all lands).[68]

The Roman Empire was among the most powerful economic, cultural, political and military forces in the world of its time, and it was one of the largest empires in world history. At its height under Trajan, it covered 5 million square kilometres.[69][70] The Roman legacy has deeply influenced the Western civilisation, shaping most of the modern world; among the many legacies of Roman dominance are the widespread use of the Romance languages derived from Latin, the numerical system, the modern Western alphabet and calendar, and the emergence of Christianity as a major world religion.[71] The Indo-Roman trade relations, beginning around the 1st century BCE, testifies to extensive Roman trade in far away regions; many reminders of the commercial trade between the Indian subcontinent and Italy have been found, such as the ivory statuette Pompeii Lakshmi from the ruins of Pompeii.

In a slow decline since the third century AD, the Empire split in two in 395 AD. The Western Empire, under the pressure of the barbarian invasions, eventually dissolved in 476 AD when its last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by the Germanic chief Odoacer. The Eastern half of the Empire survived for another thousand years.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy fell under the power of Odoacer's kingdom, and, later, was seized by the Ostrogoths,[72] followed in the 6th century by a brief reconquest under Byzantine Emperor Justinian. The invasion of another Germanic tribe, the Lombards, late in the same century, reduced the Byzantine presence to the rump realm of the Exarchate of Ravenna and started the end of political unity of the peninsula for the next 1,300 years. Invasions of the peninsula caused a chaotic succession of barbarian kingdoms and the so-called "dark ages". The Lombard kingdom was subsequently absorbed into the Frankish Empire by Charlemagne in the late 8th century. The Franks also helped the formation of the Papal States in central Italy. Until the 13th century, Italian politics was dominated by the relations between the Holy Roman Emperors and the Papacy, with most of the Italian city-states siding with the former (Ghibellines) or with the latter (Guelphs) from momentary convenience.[73]

The Germanic Emperor and the Roman Pontiff became the universal powers of medieval Europe. However, the conflict for the investiture controversy (a conflict over two radically different views of whether secular authorities such as kings, counts, or dukes, had any legitimate role in appointments to ecclesiastical offices) and the clash between Guelphs and Ghibellines led to the end of the Imperial-feudal system in the north of Italy where city-states gained independence. It was during this chaotic era that Italian towns saw the rise of a peculiar institution, the medieval commune. Given the power vacuum caused by extreme territorial fragmentation and the struggle between the Empire and the Holy See, local communities sought autonomous ways to maintain law and order.[75] The investiture controversy was finally resolved by the Concordat of Worms. In 1176 a league of city-states, the Lombard League, defeated the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano, thus ensuring effective independence for most of northern and central Italian cities.

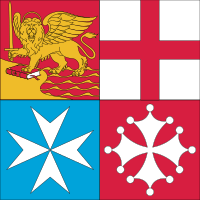

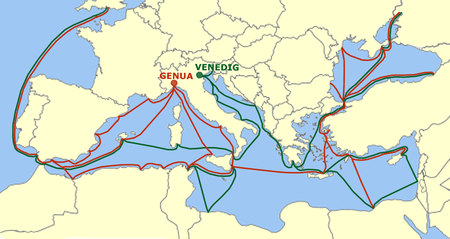

Italian city-states such as Milan, Florence and Venice played a crucial innovative role in financial development, devising the main instruments and practices of banking and the emergence of new forms of social and economic organization.[76] In coastal and southern areas, the maritime republics grew to eventually dominate the Mediterranean and monopolise trade routes to the Orient. They were independent thalassocratic city-states, though most of them originated from territories once belonging to the Byzantine Empire. All these cities during the time of their independence had similar systems of government in which the merchant class had considerable power. Although in practice these were oligarchical, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy, the relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.[77] The four best known maritime republics were Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi; the others were Ancona, Gaeta, Noli, and Ragusa.[78][79][80] Each of the maritime republics had dominion over different overseas lands, including many Mediterranean islands (especially Sardinia and Corsica), lands on the Adriatic, Aegean, and Black Sea (Crimea), and commercial colonies in the Near East and in North Africa. Venice maintained enormous tracts of land in Greece, Cyprus, Istria and Dalmatia until as late as the mid-17th century.[81]

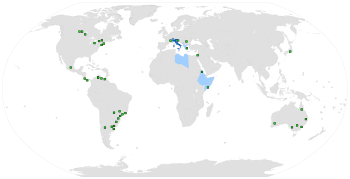

Right: Trade routes and colonies of the Genoese (red) and Venetian (green) empires.

Venice and Genoa were Europe's main gateway to trade with the East, and a producer of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of silk, wool, banks and jewellery. The wealth such business brought to Italy meant that large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned. The republics were heavily involved in the Crusades, providing support and transport, but most especially taking advantage of the political and trading opportunities resulting from these wars.[77] Italy first felt huge economic changes in Europe which led to the commercial revolution: the Republic of Venice was able to defeat the Byzantine Empire and finance the voyages of Marco Polo to Asia; the first universities were formed in Italian cities, and scholars such as Thomas Aquinas obtained international fame; Frederick of Sicily made Italy the political-cultural centre of a reign that temporarily included the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Jerusalem; capitalism and banking families emerged in Florence, where Dante and Giotto were active around 1300.[22]

In the south, Sicily had become an Islamic emirate in the 9th century, thriving until the Italo-Normans conquered it in the late 11th century together with most of the Lombard and Byzantine principalities of southern Italy.[82] Through a complex series of events, southern Italy developed as a unified kingdom, first under the House of Hohenstaufen, then under the Capetian House of Anjou and, from the 15th century, the House of Aragon. In Sardinia, the former Byzantine provinces became independent states known in Italian as Judicates, although some parts of the island fell under Genoese or Pisan rule until the eventual Aragonese annexation in the 15th century. The Black Death pandemic of 1348 left its mark on Italy by killing perhaps one third of the population.[83][84] However, the recovery from the plague led to a resurgence of cities, trade and economy which allowed the bloom of Humanism and Renaissance, that later spread to Europe.

Early Modern

Italy was the birthplace and heart of the Renaissance during the 1400s and 1500s. The Italian Renaissance marked the transition from the medieval period to the modern age as Europe recovered, economically and culturally, from the crises of the Late Middle Ages and entered the Early Modern Period. The Italian polities were now regional states effectively ruled by Princes, de facto monarchs in control of trade and administration, and their courts became major centres of Arts and Sciences. The Italian princedoms represented a first form of modern states as opposed to feudal monarchies and multinational empires. The princedoms were led by political dynasties and merchant families such as the Medici in Florence, the Visconti and Sforza in the Duchy of Milan, the Doria in the Republic of Genoa, the Mocenigo and Barbarigo in the Republic of Venice, the Este in Ferrara, and the Gonzaga in Mantua.[85][86] The Renaissance was therefore a result of the great wealth accumulated by Italian merchant cities combined with the patronage of its dominant families.[85] Italian Renaissance exercised a dominant influence on subsequent European painting and sculpture for centuries afterwards, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giotto, Donatello, and Titian, and architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Donato Bramante.

Following the conclusion of the western schism in favor of Rome at the Council of Constance (1415–1417), the new Pope Martin V returned to the Papal States after a three years-long journey that touched many Italian cities and restored Italy as the sole centre of Western Christianity. During the course of this voyage, the Medici Bank was made the official credit institution of the Papacy and several significant ties were established between the Church and the new political dynasties of the peninsula. The Popes' status as elective monarchs turned the conclaves and consistories of the Renaissance into political battles between the courts of Italy for primacy in the peninsula and access to the immense resources of the Catholic Church. In 1439, Pope Eugenius IV and the Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaiologos signed a reconciliation agreement between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence hosted by Cosimo the old de Medici. In 1453, Italian forces under Giovanni Giustiniani were sent by Pope Nicholas V to defend the Walls of Constantinople but the decisive battle was lost to the more advanced Turkish army equipped with cannons, and Byzantium fell to Sultan Mehmed II.

The fall of Constantinople led to the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy, fueling the rediscovery of Greco-Roman Humanism.[87][88][89] Humanist rulers such as Federico da Montefeltro and Pope Pius II worked to establish ideal cities where man is the measure of all things, and therefore founded Urbino and Pienza respectively. Pico della Mirandola wrote the Oration on the Dignity of Man, considered the manifesto of Renaissance Humanism, in which he stressed the importance of free will in human beings. The humanist historian Leonardo Bruni was the first to divide human history in three periods: Antiquity, Middle Ages and Modernity.[90] The second consequence of the Fall of Constantinople was the beginning of the Age of Discovery.

Italian explorers and navigators from the dominant maritime republics, eager to find an alternative route to the Indies in order to bypass the Ottoman Empire, offered their services to monarchs of Atlantic countries and played a key role in ushering the Age of Discovery and the European colonization of the Americas. The most notable among them were: Christopher Columbus, colonizer in the name of Spain, who is credited with discovering the New World and the opening of the Americas for conquest and settlement by Europeans;[91] John Cabot, sailing for England, who was the first European to set foot in "New Found Land" and explore parts of the North American continent in 1497;[92] Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for Portugal, who first demonstrated in about 1501 that the New World (in particular Brazil) was not Asia as initially conjectured, but a fourth continent previously unknown to people of the Old World (America is named after him);[93][94] and Giovanni da Verrazzano, at the service of France, renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between Florida and New Brunswick in 1524;[95]

Following the fall of Constantinople, the wars in Lombardy came to an end and a defensive alliance known as Italic League was formed between Venice, Naples, Florence, Milan, and the Papacy. Lorenzo the Magnificent de Medici was the greatest Florentine patron of the Renaissance and supporter of the Italic League. He notably avoided the collapse of the League in the aftermath of the Pazzi Conspiracy and during the aborted invasion of Italy by the Turks. However, the military campaign of Charles VIII of France in Italy caused the end of the Italic League and initiated the Italian Wars between the Valois and the Habsburgs. During the High Renaissance of the 1500s, Italy was therefore both the main European battleground and the cultural-economic centre of the continent. Popes such as Julius II (1503–1513) fought for the control of Italy against foreign monarchs, others such as Paul III (1534–1549) preferred to mediate between the European powers in order to secure peace in Italy. In the middle of this conflict, the Medici popes Leo X (1513–1521) and Clement VII (1523–1534) opposed the Protestant reformation and advanced the interests of their family. The end of the wars ultimately left northern Italy indirectly subject to the Austrian Habsburgs and Southern Italy under direct Spanish Habsburg rule.

The Papacy remained independent and launched the Counter-reformation. Key events of the period include: the Council of Trent (1545–1563); the excommunication of Elizabeth I (1570) and the Battle of Lepanto (1571), both occurring during the pontificate of Pius V; the construction of the Gregorian observatory, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, and the Jesuit China mission of Matteo Ricci under Pope Gregory XIII; the French Wars of Religion; the Long Turkish War and the execution of Giordano Bruno in 1600, under Pope Clement VIII; the birth of the Lyncean Academy of the Papal States, of which the main figure was Galileo Galilei (later put on trial); the final phases of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) during the pontificates of Urban VIII and Innocent X; and the formation of the last Holy League by Innocent XI during the Great Turkish War

The Italian economy declined during the 1600s and 1700s, as the peninsula was excluded from the rising Atlantic slave trade. Following the European wars of succession of the 18th century, the south passed to a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons and the North fell under the influence of the Habsburg-Lorraine of Austria. During the Coalition Wars, northern-central Italy was reorganised by Napoleon in a number of Sister Republics of France and later as a Kingdom of Italy in personal union with the French Empire.[96] The southern half of the peninsula was administered by Joachim Murat, Napoleon's brother-in-law, who was crowned as King of Naples. The 1814 Congress of Vienna restored the situation of the late 18th century, but the ideals of the French Revolution could not be eradicated, and soon re-surfaced during the political upheavals that characterised the first part of the 19th century.

Italian unification

.jpg)

.jpg)

The birth of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula. Following the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the political and social Italian unification movement, or Risorgimento, emerged to unite Italy consolidating the different states of the peninsula and liberate it from foreign control. A prominent radical figure was the patriotic journalist Giuseppe Mazzini, member of the secret revolutionary society Carbonari and founder of the influential political movement Young Italy in the early 1830s, who favoured a unitary republic and advocated a broad nationalist movement. His prolific output of propaganda helped the unification movement stay active.

The most famous member of Young Italy was the revolutionary and general Giuseppe Garibaldi, renowned for his extremely loyal followers,[99] who led the Italian republican drive for unification in Southern Italy. However, the Northern Italy monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had ambitions of establishing a united Italian state. In the context of the 1848 liberal revolutions that swept through Europe, an unsuccessful first war of independence was declared on Austria. In 1855, the Kingdom of Sardinia became an ally of Britain and France in the Crimean War, giving Cavour's diplomacy legitimacy in the eyes of the great powers.[100][101] The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in liberating Lombardy.

In 1860–1861, Garibaldi led the drive for unification in Naples and Sicily (the Expedition of the Thousand),[102] while the House of Savoy troops occupied the central territories of the Italian peninsula, except Rome and part of Papal States. Teano was the site of the famous meeting of 26 October 1860 between Giuseppe Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II, last King of Sardinia, in which Garibaldi shook Victor Emanuel's hand and hailed him as King of Italy; thus, Garibaldi sacrificed republican hopes for the sake of Italian unity under a monarchy. Cavour agreed to include Garibaldi's Southern Italy allowing it to join the union with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. This allowed the Sardinian government to declare a united Italian kingdom on 17 March 1861.[103] Victor Emmanuel II then became the first king of a united Italy, and the capital was moved from Turin to Florence.

In 1866, Victor Emmanuel II allied with Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War, waging the Third Italian War of Independence which allowed Italy to annexe Venetia. Finally, in 1870, as France abandoned its garrisons in Rome during the disastrous Franco-Prussian War to keep the large Prussian Army at bay, the Italians rushed to fill the power gap by taking over the Papal States. Italian unification was completed and shortly afterward Italy's capital was moved to Rome. Victor Emmanuel, Garibaldi, Cavour and Mazzini have been referred as Italy's Four Fathers of the Fatherland.[97]

Monarchical period

The new Kingdom of Italy obtained Great Power status. The Constitutional Law of the Kingdom of Sardinia the Albertine Statute of 1848, was extended to the whole Kingdom of Italy in 1861, and provided for basic freedoms of the new State, but electoral laws excluded the non-propertied and uneducated classes from voting. The government of the new kingdom took place in a framework of parliamentary constitutional monarchy dominated by liberal forces. As Northern Italy quickly industrialised, the South and rural areas of the North remained underdeveloped and overpopulated, forcing millions of people to migrate abroad and fuelling a large and influential diaspora. The Italian Socialist Party constantly increased in strength, challenging the traditional liberal and conservative establishment.

Starting from the last two decades of the 19th century, Italy developed into a colonial power by forcing under its rule Eritrea and Somalia in East Africa, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in North Africa (later unified in the colony of Libya) and the Dodecanese islands.[104] From 2 November 1899 to 7 September 1901, Italy also participated as part of the Eight-Nation Alliance forces during the Boxer Rebellion in China; on 7 September 1901, a concession in Tientsin was ceded to the country, and on 7 June 1902, the concession was taken into Italian possession and administered by a consul. In 1913, male universal suffrage was adopted. The pre-war period dominated by Giovanni Giolitti, Prime Minister five times between 1892 and 1921, was characterized by the economic, industrial and political-cultural modernization of Italian society.

Italy, nominally allied with the German Empire and the Empire of Austria-Hungary in the Triple Alliance, in 1915 joined the Allies into World War I with a promise of substantial territorial gains, that included western Inner Carniola, former Austrian Littoral, Dalmatia as well as parts of the Ottoman Empire. The country gave a fundamental contribution to the victory of the conflict as one of the "Big Four" top Allied powers. The war was initially inconclusive, as the Italian army got stuck in a long attrition war in the Alps, making little progress and suffering very heavy losses. However, the reorganization of the army and the conscription of the so-called '99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99, all males born in 1899 who were turning 18) led to more effective Italian victories in major battles, such as on Monte Grappa and in a series of battles on the Piave river. Eventually, in October 1918, the Italians launched a massive offensive, culminating in the victory of Vittorio Veneto. The Italian victory[105][106][107] marked the end of the war on the Italian Front, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was chiefly instrumental in ending the First World War less than two weeks later.

During the war, more than 650,000 Italian soldiers and as many civilians died[108] and the kingdom went to the brink of bankruptcy. Under the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain, Rapallo and Rome, Italy gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council and obtained most of the promised territories, but not Dalmatia (except Zara), allowing nationalists to define the victory as "mutilated". Moreover, Italy annexed the Hungarian harbour of Fiume, that was not part of territories promised at London but had been occupied after the end of the war by Gabriele D'Annunzio.

Fascist regime

The socialist agitations that followed the devastation of the Great War, inspired by the Russian Revolution, led to counter-revolution and repression throughout Italy. The liberal establishment, fearing a Soviet-style revolution, started to endorse the small National Fascist Party, led by Benito Mussolini. In October 1922 the Blackshirts of the National Fascist Party attempted a coup named the "March on Rome" which failed but at the last minute, King Victor Emmanuel III refused to proclaim a state of siege and appointed Mussolini prime minister. Over the next few years, Mussolini banned all political parties and curtailed personal liberties, thus forming a dictatorship. These actions attracted international attention and eventually inspired similar dictatorships such as Nazi Germany and Francoist Spain.

In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia and founded the Italian East Africa, resulting in an international alienation and leading to Italy's withdrawal from the League of Nations; Italy allied with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan and strongly supported Francisco Franco in the Spanish civil war. In 1939, Italy annexed Albania, a de facto protectorate for decades. Italy entered World War II on 10 June 1940. After initially advancing in British Somaliland, Egypt, the Balkans and eastern fronts, the Italians were defeated in East Africa, Soviet Union and North Africa.

The Armistice of Villa Giusti, which ended fighting between Italy and Austria-Hungary at the end of World War I, resulted in Italian annexation of neighbouring parts of Yugoslavia. During the interwar period, the fascist Italian government undertook a campaign of Italianisation in the areas it annexed, which suppressed Slavic language, schools, political parties, and cultural institutions. During World War II, Italian war crimes included extrajudicial killings and ethnic cleansing[109] by deportation of about 25,000 people, mainly Jews, Croats, and Slovenians, to the Italian concentration camps, such as Rab, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari and elsewhere. In Italy and Yugoslavia, unlike in Germany, few war crimes were prosecuted.[110][111][112][113] Yugoslav Partisans perpetrated their own crimes during and after the war, including the foibe killings. Meanwhile, about 250,000 Italians and anti-communist Slavs fled to Italy in the Istrian exodus.

An Allied invasion of Sicily began in July 1943, leading to the collapse of the Fascist regime and the fall of Mussolini on 25 July. Mussolini was deposed and arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III in co-operation with the majority of the members of the Grand Council of Fascism, which passed a motion of no confidence. On 8 September, Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile, ending its war with the Allies. The Germans helped by the Italian fascists shortly succeeded in taking control of northern and central Italy. The country remained a battlefield for the rest of the war, as the Allies were slowly moving up from the south.

In the north, the Germans set up the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a Nazi puppet state with Mussolini installed as leader after he was rescued by German paratroopers. Some Italian troops in the south were organized into the Italian Co-belligerent Army, which fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war, while other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini and his RSI, continued to fight alongside the Germans in the National Republican Army. As result, the country descended into civil war. Also, the post-armistice period saw the rise of a large anti-fascist resistance movement, the Resistenza, which fought a guerilla war against the German and RSI forces. In late April 1945, with total defeat looming, Mussolini attempted to escape north,[114] but was captured and summarily executed near Lake Como by Italian partisans. His body was then taken to Milan, where it was hung upside down at a service station for public viewing and to provide confirmation of his demise.[115] Hostilities ended on 29 April 1945, when the German forces in Italy surrendered. Nearly half a million Italians (including civilians) died in the conflict,[116] and the Italian economy had been all but destroyed; per capita income in 1944 was at its lowest point since the beginning of the 20th century.[117]

Republican Italy

Italy became a republic after a referendum[118] held on 2 June 1946, a day celebrated since as Republic Day. This was also the first time that Italian women were entitled to vote.[119] Victor Emmanuel III's son, Umberto II, was forced to abdicate and exiled. The Republican Constitution was approved on 1 January 1948. Under the Treaty of Peace with Italy of 1947, most of the Julian March was lost to Yugoslavia and, later, the Free Territory of Trieste was divided between the two states. Italy also lost all of its colonial possessions, formally ending the Italian Empire. In 1950, Italian Somaliland was made a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration until 1 July 1960.

Fears of a possible Communist takeover (especially in the United States) proved crucial for the first universal suffrage electoral outcome on 18 April 1948, when the Christian Democrats, under the leadership of Alcide De Gasperi, obtained a landslide victory.[120][121] Consequently, in 1949 Italy became a member of NATO. The Marshall Plan helped to revive the Italian economy which, until the late 1960s, enjoyed a period of sustained economic growth commonly called the "Economic Miracle". In 1957, Italy was a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC), which became the European Union (EU) in 1993.

From the late 1960s until the early 1980s, the country experienced the Years of Lead, a period characterised by economic crisis (especially after the 1973 oil crisis), widespread social conflicts and terrorist massacres carried out by opposing extremist groups, with the alleged involvement of US and Soviet intelligence.[122][123][124] The Years of Lead culminated in the assassination of the Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro in 1978 and the Bologna railway station massacre in 1980, where 85 people died.

In the 1980s, for the first time since 1945, two governments were led by non-Christian-Democrat premiers: one republican (Giovanni Spadolini) and one socialist (Bettino Craxi); the Christian Democrats remained, however, the main government party. During Craxi's government, the economy recovered and Italy became the world's fifth largest industrial nation, after it gained the entry into the Group of Seven in the 1970s. However, as a result of his spending policies, the Italian national debt skyrocketed during the Craxi era, soon passing 100% of the country's GDP.

Italy faced several terror attacks between 1992–93 perpetrated by the Sicilian Mafia as a consequence of several life sentences pronounced during the "Maxi Trial", and of the new anti-mafia measures launched by the government. In 1992, two major dynamite attacks killed the judges Giovanni Falcone (23 May in the Capaci bombing) and Paolo Borsellino (19 July in the Via D'Amelio bombing).[125] One year later (May–July 1993), tourist spots were attacked, such as the Via dei Georgofili in Florence, Via Palestro in Milan, and the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano and Via San Teodoro in Rome, leaving 10 dead and 93 injured and causing severe damage to cultural heritage such as the Uffizi Gallery. The Catholic Church openly condemned the Mafia, and two churches were bombed and an anti-Mafia priest shot dead in Rome.[126][127][128] Also in the early 1990s, Italy faced significant challenges, as voters – disenchanted with political paralysis, massive public debt and the extensive corruption system (known as Tangentopoli) uncovered by the Clean Hands (Mani Pulite) investigation – demanded radical reforms. The scandals involved all major parties, but especially those in the government coalition: the Christian Democrats, who ruled for almost 50 years, underwent a severe crisis and eventually disbanded, splitting up into several factions.[129] The Communists reorganised as a social-democratic force. During the 1990s and the 2000s, centre-right (dominated by media magnate Silvio Berlusconi) and centre-left coalitions (led by university professor Romano Prodi) alternately governed the country.

Amidst the Great Recession, Berlusconi resigned in 2011, and his conservative government was replaced by the technocratic cabinet of Mario Monti.[130] Following the 2013 general election, the Vice-Secretary of the Democratic Party Enrico Letta formed a new government at the head of a right-left Grand coalition. In 2014, challenged by the new Secretary of the PD Matteo Renzi, Letta resigned and was replaced by Renzi. The new government started important constitutional reforms such as the abolition of the Senate and a new electoral law. On 4 December the constitutional reform was rejected in a referendum and Renzi resigned; the Foreign Affairs Minister Paolo Gentiloni was appointed new Prime Minister.[131]

In the European migrant crisis of the 2010s, Italy was the entry point and leading destination for most asylum seekers entering the EU. From 2013 to 2018, the country took in over 700,000 migrants and refugees,[132] mainly from sub-Saharan Africa,[133] which caused great strain on the public purse and a surge in the support for far-right or eurosceptic political parties.[134][135] The 2018 general election was characterized by a strong showing of the Five Star Movement and the League and the university professor Giuseppe Conte became the Prime Minister at the head of a populist coalition between these two parties.[136] However, after only fourteen months the League withdrew its support to Conte, who formed a new unprecedented government coalition between the Five Star Movement and the centre-left.[137][138]

In 2020, Italy was severely hit by a coronavirus pandemic, originating from Wuhan, China.[139] From March to May, Conte's government imposed a national quarantine, as a measure to limit the spread of the pandemic.[140][141] The measures, despite being widely approved by the public opinion,[142] were also described as the largest suppression of constitutional rights in the history of the republic.[143][144] With more than 35,000 confirmed victims, Italy was one of the countries with the highest total number of deaths in the worldwide coronavirus pandemic.[145] The pandemic caused also a severe economic disruption, in which Italy resulted as one of the most affected countries.[146]

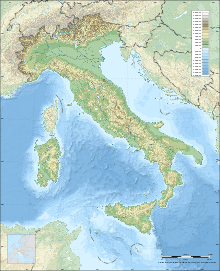

Geography

Italy is located in Southern Europe (it is also considered a part of western Europe)[17] between latitudes 35° and 47° N, and longitudes 6° and 19° E. To the north, Italy borders France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia and is roughly delimited by the Alpine watershed, enclosing the Po Valley and the Venetian Plain. To the south, it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula and the two Mediterranean islands of Sicily and Sardinia (the two biggest islands of the Mediterranean), in addition to many smaller islands. The sovereign states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy,[147][148] while Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland.[149]

The country's total area is 301,230 square kilometres (116,306 sq mi), of which 294,020 km2 (113,522 sq mi) is land and 7,210 km2 (2,784 sq mi) is water.[150] Including the islands, Italy has a coastline and border of 7,600 kilometres (4,722 miles) on the Adriatic, Ionian, Tyrrhenian seas (740 km (460 mi)), and borders shared with France (488 km (303 mi)), Austria (430 km (267 mi)), Slovenia (232 km (144 mi)) and Switzerland (740 km (460 mi)). San Marino (39 km (24 mi)) and Vatican City (3.2 km (2.0 mi)), both enclaves, account for the remainder.[150]

Over 35% of the Italian territory is mountainous.[151] The Apennine Mountains form the peninsula's backbone, and the Alps form most of its northern boundary, where Italy's highest point is located on Mont Blanc (Monte Bianco) (4,810 m or 15,780 ft).[note 1] Other worldwide-known mountains in Italy include the Matterhorn (Monte Cervino), Monte Rosa, Gran Paradiso in the West Alps, and Bernina, Stelvio and Dolomites along the eastern side.

The Po, Italy's longest river (652 kilometres or 405 miles), flows from the Alps on the western border with France and crosses the Padan plain on its way to the Adriatic Sea. The Po Valley is the largest plain in Italy, with 46,000 km2 (18,000 sq mi), and it represents over 70% of the total plain area in the country.[151]

Many elements of the Italian territory are of volcanic origin. Most of the small islands and archipelagos in the south, like Capraia, Ponza, Ischia, Eolie, Ustica and Pantelleria are volcanic islands. There are also active volcanoes: Mount Etna in Sicily (the largest active volcano in Europe), Vulcano, Stromboli, and Vesuvius (the only active volcano on mainland Europe).

The five largest lakes are, in order of diminishing size:[152] Garda (367.94 km2 or 142 sq mi), Maggiore (212.51 km2 or 82 sq mi, whose minor northern part is Switzerland), Como (145.9 km2 or 56 sq mi), Trasimeno (124.29 km2 or 48 sq mi) and Bolsena (113.55 km2 or 44 sq mi).

Although the country includes the Italian peninsula, adjacent islands, and most of the southern Alpine basin, some of Italy's territory extends beyond the Alpine basin and some islands are located outside the Eurasian continental shelf. These territories are the comuni of: Livigno, Sexten, Innichen, Toblach (in part), Chiusaforte, Tarvisio, Graun im Vinschgau (in part), which are all part of the Danube's drainage basin, while the Val di Lei constitutes part of the Rhine's basin and the islands of Lampedusa and Lampione are on the African continental shelf.

Waters

Four different seas surround the Italian Peninsula in the Mediterranean Sea from three sides: the Adriatic Sea in the east,[153] the Ionian Sea in the south,[154] and the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea in the west.[155]

Most of the rivers of Italy drain either into the Adriatic Sea, such as the Po, Piave, Adige, Brenta, Tagliamento, and Reno, or into the Tyrrhenian, like the Arno, Tiber and Volturno. The waters from some border municipalities (Livigno in Lombardy, Innichen and Sexten in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol) drain into the Black Sea through the basin of the Drava, a tributary of the Danube, and the waters from the Lago di Lei in Lombardy drain into the North Sea through the basin of the Rhine.[156]

In the north of the country are a number of subalpine moraine-dammed lakes, the largest of which is Garda (370 km2 or 143 sq mi). Other well-known subalpine lakes are Lake Maggiore (212.5 km2 or 82 sq mi), whose most northerly section is part of Switzerland, Como (146 km2 or 56 sq mi), one of the deepest lakes in Europe, Orta, Lugano, Iseo, and Idro.[157] Other notable lakes in the Italian peninsula are Trasimeno, Bolsena, Bracciano, Vico, Varano and Lesina in Gargano and Omodeo in Sardinia.[158]

Volcanology

The country is situated at the meeting point of the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate, leading to considerable seismic and volcanic activity. There are 14 volcanoes in Italy, four of which are active: Etna, Stromboli, Vulcano and Vesuvius. The last is the only active volcano in mainland Europe and is most famous for the destruction of Pompeii and Herculanum in the eruption in 79 AD. Several islands and hills have been created by volcanic activity, and there is still a large active caldera, the Campi Flegrei north-west of Naples.

The high volcanic and magmatic neogenic activity is subdivided into provinces:

- Magmatic Tuscan (Monti Cimini, Tolfa and Amiata);[159][160]

- Magmatic Latium (Monti Volsini, Vico nel Lazio, Colli Albani, Roccamonfina);[160][161]

- Ultra-alkaline Umbrian Latium District (San Venanzo, Cupaello and Polino);[160][161]

- Volcanic bell (Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, Ischia);[160][161]

- Windy arch and Tyrrhenian basin (Aeolian Islands and Tyrrhenian seamounts);[160][161]

- African-Adriatic Avampa (Channel of Sicily, Graham Island, Etna and Mount Vulture).[160][161]

Italy was the first country to exploit geothermal energy to produce electricity.[162] The high geothermal gradient that forms part of the peninsula makes potentially exploitable also other provinces: research carried out in the 1960s and 1970s identifies potential geothermal fields in Lazio and Tuscany, as well as in most volcanic islands.[162]

Environment

After its quick industrial growth, Italy took a long time to confront its environmental problems. After several improvements, it now ranks 84th in the world for ecological sustainability.[163] National parks cover about 5% of the country.[164] In the last decade, Italy has become one of the world's leading producers of renewable energy, ranking as the world's fourth largest holder of installed solar energy capacity[165][166] and the sixth largest holder of wind power capacity in 2010.[167] Renewable energies now make up about 12% of the total primary and final energy consumption in Italy, with a future target share set at 17% for the year 2020.[168] However, air pollution remains a severe problem, especially in the industrialised north, reaching the tenth highest level worldwide of industrial carbon dioxide emissions in the 1990s.[169] Italy is the twelfth largest carbon dioxide producer.[170][171] Extensive traffic and congestion in the largest metropolitan areas continue to cause severe environmental and health issues, even if smog levels have decreased dramatically since the 1970s and 1980s, and the presence of smog is becoming an increasingly rarer phenomenon and levels of sulphur dioxide are decreasing.[172]

_naar_Colle_Tsa_S%C3%A8tse_in_Cogne_Valley_(Itali%C3%AB)._Zicht_op_de_omringende_alpentoppen_van_Gran_Paradiso_06.jpg)

Many watercourses and coastal stretches have also been contaminated by industrial and agricultural activity, while because of rising water levels, Venice has been regularly flooded throughout recent years. Waste from industrial activity is not always disposed of by legal means and has led to permanent health effects on inhabitants of affected areas, as in the case of the Seveso disaster. The country has also operated several nuclear reactors between 1963 and 1990 but, after the Chernobyl disaster and a referendum on the issue the nuclear programme was terminated, a decision that was overturned by the government in 2008, planning to build up to four nuclear power plants with French technology. This was in turn struck down by a referendum following the Fukushima nuclear accident.[173]

Deforestation, illegal building developments and poor land-management policies have led to significant erosion all over Italy's mountainous regions, leading to major ecological disasters like the 1963 Vajont Dam flood, the 1998 Sarno[174] and 2009 Messina mudslides.

Biodiversity

Italy has the highest level of faunal biodiversity in Europe, with over 57,000 species recorded, representing more than a third of all European fauna.[176] Italy's varied geological structure contributes to its high climate and habitat diversity. The Italian peninsula is in the centre of the Mediterranean Sea, forming a corridor between central Europe and North Africa, and has 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of coastline. Italy also receives species from the Balkans, Eurasia, the Middle East. Italy's varied geological structure, including the Alps and the Apennines, Central Italian woodlands, and Southern Italian Garigue and Maquis shrubland, also contributes to high climate and habitat diversity.

Italian fauna includes 4,777 endemic animal species, which include the Sardinian long-eared bat, Sardinian red deer, spectacled salamander, brown cave salamander, Italian newt, Italian frog, Apennine yellow-bellied toad, Aeolian wall lizard, Sicilian wall lizard, Italian Aesculapian snake, and Sicilian pond turtle. There are 102 mammals species (most notably the Italian wolf, Marsican brown bear, Pyrenean chamois, Alpine ibex, crested porcupine, Mediterranean monk seal, Alpine marmot, Etruscan shrew, and European snow vole), 516 bird species and 56,213 invertebrate species.

The flora of Italy was traditionally estimated to comprise about 5,500 vascular plant species.[177] However, as of 2005, 6,759 species are recorded in the Data bank of Italian vascular flora.[178] Italy is a signatory to the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and the Habitats Directive both affording protection to Italian fauna and flora.

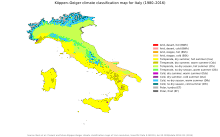

Climate

Because of the great longitudinal extension of the peninsula and the mostly mountainous internal conformation, the climate of Italy is highly diverse. In most of the inland northern and central regions, the climate ranges from humid subtropical to humid continental and oceanic. In particular, the climate of the Po valley geographical region is mostly continental, with harsh winters and hot summers.[180][181]

The coastal areas of Liguria, Tuscany and most of the South generally fit the Mediterranean climate stereotype (Köppen climate classification Csa). Conditions on peninsular coastal areas can be very different from the interior's higher ground and valleys, particularly during the winter months when the higher altitudes tend to be cold, wet, and often snowy. The coastal regions have mild winters and warm and generally dry summers, although lowland valleys can be quite hot in summer. Average winter temperatures vary from 0 °C (32 °F) on the Alps to 12 °C (54 °F) in Sicily, so average summer temperatures range from 20 °C (68 °F) to over 25 °C (77 °F). Winters can vary widely across the country with lingering cold, foggy and snowy periods in the north and milder, sunnier conditions in the south. Summers can be hot and humid across the country, particularly in the south while northern and central areas can experience occasional strong thunderstorms from spring to autumn.[182]

Politics

Italy has been a unitary parliamentary republic since 2 June 1946, when the monarchy was abolished by a constitutional referendum. The President of Italy (Presidente della Repubblica), currently Sergio Mattarella since 2015, is Italy's head of state. The President is elected for a single seven years mandate by the Parliament of Italy and some regional voters in joint session. Italy has a written democratic constitution, resulting from the work of a Constituent Assembly formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the Civil War.[183]

Government

Italy has a parliamentary government based on a mixed proportional and majoritarian voting system. The parliament is perfectly bicameral: the two houses, the Chamber of Deputies that meets in Palazzo Montecitorio, and the Senate of the Republic that meets in Palazzo Madama, have the same powers. The Prime Minister, officially President of the Council of Ministers (Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is Italy's head of government. The Prime Minister and the cabinet are appointed by the President of the Republic of Italy and must pass a vote of confidence in Parliament to come into office. To remain the Prime Minister has to pass also eventual further votes of confidence or no confidence in Parliament.

The prime minister is the President of the Council of Ministers – which holds effective executive power – and he must receive a vote of approval from it to execute most political activities. The office is similar to those in most other parliamentary systems, but the leader of the Italian government is not authorised to request the dissolution of the Parliament of Italy.

Another difference with similar offices is that the overall political responsibility for intelligence is vested in the President of the Council of Ministers. By virtue of that, the Prime Minister has exclusive power to: co-ordinate intelligence policies, determining the financial resources and strengthening national cyber security; apply and protect State secrets; authorise agents to carry out operations, in Italy or abroad, in violation of the law.[184]

A peculiarity of the Italian Parliament is the representation given to Italian citizens permanently living abroad: 12 Deputies and 6 Senators elected in four distinct overseas constituencies. In addition, the Italian Senate is characterised also by a small number of senators for life, appointed by the President "for outstanding patriotic merits in the social, scientific, artistic or literary field". Former Presidents of the Republic are ex officio life senators.

Italy's three major political parties are the Five Star Movement, the Democratic Party and the Lega. During the 2018 general election these three parties won 614 out of 630 seats available in the Chamber of Deputies and 309 out of 315 in the Senate.[185] Berlusconi's Forza Italia which formed a centre-right coalition with Matteo Salvini's Northern League and Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy won most of the seats without getting the majority in parliament. The rest of the seats were taken by Five Star Movement, Matteo Renzi's Democratic Party along with Achammer and Panizza's South Tyrolean People's Party & Trentino Tyrolean Autonomist Party in a centre-left coalition and the independent Free and Equal party.

Law and criminal justice

The Italian judicial system is based on Roman law modified by the Napoleonic code and later statutes. The Supreme Court of Cassation is the highest court in Italy for both criminal and civil appeal cases. The Constitutional Court of Italy (Corte Costituzionale) rules on the conformity of laws with the constitution and is a post–World War II innovation. Since their appearance in the middle of the 19th century, Italian organised crime and criminal organisations have infiltrated the social and economic life of many regions in Southern Italy, the most notorious of which being the Sicilian Mafia, which would later expand into some foreign countries including the United States. Mafia receipts may reach 9%[186][187] of Italy's GDP.[188]

A 2009 report identified 610 comuni which have a strong Mafia presence, where 13 million Italians live and 14.6% of the Italian GDP is produced.[189][190] The Calabrian 'Ndrangheta, nowadays probably the most powerful crime syndicate of Italy, accounts alone for 3% of the country's GDP.[191] However, at 0.013 per 1,000 people, Italy has only the 47th highest murder rate[192] compared to 61 countries and the 43rd highest number of rapes per 1,000 people compared to 64 countries in the world. These are relatively low figures among developed countries.

Law enforcement

The Italian law enforcement system is complex, with multiple police forces.[193] The national policing agencies are the Polizia di Stato (State Police), the Arma dei Carabinieri, the Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard), and the Polizia Penitenziaria (Prison Police),[194] as well as the Guardia Costiera (coast guard police).[193]

The Polizia di Stato are a civil police supervised by the Interior Ministry, while the Carabinieri is a gendarmerie supervised by the Defense Ministry; both share duties in law enforcement and the maintenance of public order.[194] Within the Carabinieri is a unit devoted to combating environmental crime.[193] The Guardia di Finanza is responsible for combating financial crime and white-collar crime,[194] as well as customs.[193] The Polizia Penitenziaria are responsible for guarding the prison system.[194] The Corpo Forestale dello Stato (State Forestry Corps) formerly existed as a separate national park ranger agency,[193][194] but was merged into the Carabinieri in 2016.[195] Although policing in Italy is primarily provided on a national basis,[194] there also exists Polizia Provinciale (provincial police) and Polizia Municipale (municipal police).[193]

Foreign relations

Italy is a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC), now the European Union (EU), and of NATO. Italy was admitted to the United Nations in 1955, and it is a member and a strong supporter of a wide number of international organisations, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade/World Trade Organization (GATT/WTO), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the Central European Initiative. Its recent or upcoming turns in the rotating presidency of international organisations include the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe in 2018, the G7 in 2017 and the EU Council from July to December 2014. Italy is also a recurrent non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, the most recently in 2017.

Italy strongly supports multilateral international politics, endorsing the United Nations and its international security activities. As of 2013, Italy was deploying 5,296 troops abroad, engaged in 33 UN and NATO missions in 25 countries of the world.[196] Italy deployed troops in support of UN peacekeeping missions in Somalia, Mozambique, and East Timor and provides support for NATO and UN operations in Bosnia, Kosovo and Albania. Italy deployed over 2,000 troops in Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) from February 2003.

Italy supported international efforts to reconstruct and stabilise Iraq, but it had withdrawn its military contingent of some 3,200 troops by 2006, maintaining only humanitarian operators and other civilian personnel. In August 2006 Italy deployed about 2,450 troops in Lebanon for the United Nations' peacekeeping mission UNIFIL.[197] Italy is one of the largest financiers of the Palestinian National Authority, contributing €60 million in 2013 alone.[198]

Military

The Italian Army, Navy, Air Force and Carabinieri collectively form the Italian Armed Forces, under the command of the Supreme Defence Council, presided over by the President of Italy. Since 2005, military service is voluntary.[199] In 2010, the Italian military had 293,202 personnel on active duty,[200] of which 114,778 are Carabinieri.[201] Total Italian military spending in 2010 ranked tenth in the world, standing at $35.8 billion, equal to 1.7% of national GDP. As part of NATO's nuclear sharing strategy Italy also hosts 90 United States B61 nuclear bombs, located in the Ghedi and Aviano air bases.[202]

The Italian Army is the national ground defence force, numbering 109,703 in 2008. Its best-known combat vehicles are the Dardo infantry fighting vehicle, the Centauro tank destroyer and the Ariete tank, and among its aircraft the Mangusta attack helicopter, in the last years deployed in EU, NATO and UN missions. It also has at its disposal many Leopard 1 and M113 armoured vehicles.

The Italian Navy in 2008 had 35,200 active personnel with 85 commissioned ships and 123 aircraft.[203] It is a blue-water navy. In modern times the Italian Navy, being a member of the EU and NATO, has taken part in many coalition peacekeeping operations around the world.

The Italian Air Force in 2008 had a strength of 43,882 and operated 585 aircraft, including 219 combat jets and 114 helicopters. A transport capability is guaranteed by a fleet of 27 C-130Js and C-27J Spartan.

An autonomous corps of the military, the Carabinieri are the gendarmerie and military police of Italy, policing the military and civilian population alongside Italy's other police forces. While the different branches of the Carabinieri report to separate ministries for each of their individual functions, the corps reports to the Ministry of Internal Affairs when maintaining public order and security.[204]

Constituent entities

Italy is constituted by 20 regions (regioni)—five of these regions having a special autonomous status that enables them to enact legislation on additional matters, 107 provinces (province) or metropolitan cities (città metropolitane), and 7,960 municipalities (comuni).[205]

| Region | Capital | Area (km2) | Area (sq mi) | Population (January 2019) | Nominal GDP EURO billions (2016)[206] | Nominal GDP EURO per capita(2016) [207] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo | L'Aquila | 10,763 | 4,156 | 1,311,580 | 32 | 24,100 |

| Aosta Valley | Aosta | 3,263 | 1,260 | 125,666 | 4 | 34,900 |

| Apulia | Bari | 19,358 | 7,474 | 4,029,053 | 72 | 17,800 |

| Basilicata | Potenza | 9,995 | 3,859 | 562,869 | 12 | 20,600 |

| Calabria | Catanzaro | 15,080 | 5,822 | 1,947,131 | 33 | 16,800 |

| Campania | Naples | 13,590 | 5,247 | 5,801,692 | 107 | 18,300 |

| Emilia-Romagna | Bologna | 22,446 | 8,666 | 4,459,477 | 154 | 34,600 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | Trieste | 7,858 | 3,034 | 1,215,220 | 37 | 30,300 |

| Lazio | Rome | 17,236 | 6,655 | 5,879,082 | 186 | 31,600 |

| Liguria | Genoa | 5,422 | 2,093 | 1,550,640 | 48 | 30,800 |

| Lombardy | Milan | 23,844 | 9,206 | 10,060,574 | 367 | 36,600 |

| Marche | Ancona | 9,366 | 3,616 | 1,525,271 | 41 | 26,600 |

| Molise | Campobasso | 4,438 | 1,713 | 305,617 | 6 | 20,000 |

| Piedmont | Turin | 25,402 | 9,808 | 4,356,406 | 129 | 29,400 |

| Sardinia | Cagliari | 24,090 | 9,301 | 1,639,591 | 34 | 20,300 |

| Sicily | Palermo | 25,711 | 9,927 | 4,999,891 | 87 | 17,200 |

| Tuscany | Florence | 22,993 | 8,878 | 3,729,641 | 112 | 30,000 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol | Trento | 13,607 | 5,254 | 1,072,276 | 42 | 39,755 |

| Umbria | Perugia | 8,456 | 3,265 | 882,015 | 21 | 24,000 |

| Veneto | Venice | 18,399 | 7,104 | 4,905,854 | 156 | 31,700 |

Economy

Italy has a major advanced[208] capitalist mixed economy, ranking as the third-largest in the Eurozone and the eighth-largest in the world.[209] A founding member of the G7, the Eurozone and the OECD, it is regarded as one of the world's most industrialised nations and a leading country in world trade and exports.[210][211][212] It is a highly developed country, with the world's 8th highest quality of life in 2005[31] and the 26th Human Development Index. The country is well known for its creative and innovative business,[213] a large and competitive agricultural sector[214] (with the world's largest wine production),[215] and for its influential and high-quality automobile, machinery, food, design and fashion industry.[216][217][218]

Italy is the world's sixth largest manufacturing country,[221] characterised by a smaller number of global multinational corporations than other economies of comparable size and many dynamic small and medium-sized enterprises, notoriously clustered in several industrial districts, which are the backbone of the Italian industry. This has produced a manufacturing sector often focused on the export of niche market and luxury products, that if on one side is less capable to compete on the quantity, on the other side is more capable of facing the competition from China and other emerging Asian economies based on lower labour costs, with higher quality products.[222] Italy was the world's 7th largest exporter in 2016. Its closest trade ties are with the other countries of the European Union, with whom it conducts about 59% of its total trade. Its largest EU trade partners, in order of market share, are Germany (12.9%), France (11.4%), and Spain (7.4%).[223]

The automotive industry is a significant part of the Italian manufacturing sector, with over 144,000 firms and almost 485,000 employed people in 2015,[224] and a contribution of 8.5% to Italian GDP.[225] Fiat Chrysler Automobiles or FCA is currently the world's seventh-largest auto maker.[226] The country boasts a wide range of acclaimed products, from very compact city cars to luxury supercars such as Maserati, Lamborghini, and Ferrari, which was rated the world's most powerful brand by Brand Finance.[227]

Italy is part of the European single market which represents more than 500 million consumers. Several domestic commercial policies are determined by agreements among European Union (EU) members and by EU legislation. Italy introduced the common European currency, the Euro in 2002.[228][229] It is a member of the Eurozone which represents around 330 million citizens. Its monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank.

Italy has been hit hard by the Financial crisis of 2007–08, that exacerbated the country's structural problems.[230] Effectively, after a strong GDP growth of 5–6% per year from the 1950s to the early 1970s,[231] and a progressive slowdown in the 1980-90s, the country virtually stagnated in the 2000s.[232][233] The political efforts to revive growth with massive government spending eventually produced a severe rise in public debt, that stood at over 131.8% of GDP in 2017,[234] ranking second in the EU only after the Greek one.[235] For all that, the largest chunk of Italian public debt is owned by national subjects, a major difference between Italy and Greece,[236] and the level of household debt is much lower than the OECD average.[237]

A gaping North–South divide is a major factor of socio-economic weakness.[238] It can be noted by the huge difference in statistical income between the northern and southern regions and municipalities.[239] The richest province, Alto Adige-South Tyrol, earns 152% of the national GDP per capita, while the poorest region, Calabria, 61%.[240] The unemployment rate (11.1%) stands slightly above the Eurozone average,[241] but the disaggregated figure is 6.6% in the North and 19.2% in the South.[242] The youth unemployment rate (31.7% in March 2018) is extremely high compared to EU standards.[243]

Italy has a strong cooperative sector, with the largest share of the population (4.5%) employed by a cooperative in the EU.[244]

Agriculture

According to the last national agricultural census, there were 1.6 million farms in 2010 (−32.4% since 2000) covering 12.7 million hectares (63% of which are located in Southern Italy).[245] The vast majority (99%) are family-operated and small, averaging only 8 hectares in size.[245] Of the total surface area in agricultural use (forestry excluded), grain fields take up 31%, olive tree orchards 8.2%, vineyards 5.4%, citrus orchards 3.8%, sugar beets 1.7%, and horticulture 2.4%. The remainder is primarily dedicated to pastures (25.9%) and feed grains (11.6%).[245]

Italy is the world's largest wine producer,[246] and one of the leading in olive oil, fruits (apples, olives, grapes, oranges, lemons, pears, apricots, hazelnuts, peaches, cherries, plums, strawberries and kiwifruits), and vegetables (especially artichokes and tomatoes). The most famous Italian wines are probably the Tuscan Chianti and the Piedmontese Barolo. Other famous wines are Barbaresco, Barbera d'Asti, Brunello di Montalcino, Frascati, Montepulciano d'Abruzzo, Morellino di Scansano, and the sparkling wines Franciacorta and Prosecco.

Quality goods in which Italy specialises, particularly the already mentioned wines and regional cheeses, are often protected under the quality assurance labels DOC/DOP. This geographical indication certificate, which is attributed by the European Union, is considered important in order to avoid confusion with low-quality mass-produced ersatz products.

Infrastructure

.jpg)

In 2004 the transport sector in Italy generated a turnover of about 119.4 billion euros, employing 935,700 persons in 153,700 enterprises. Regarding the national road network, in 2002 there were 668,721 km (415,524 mi) of serviceable roads in Italy, including 6,487 km (4,031 mi) of motorways, state-owned but privately operated by Atlantia. In 2005, about 34,667,000 passenger cars (590 cars per 1,000 people) and 4,015,000 goods vehicles circulated on the national road network.[248]

The national railway network, state-owned and operated by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (FSI), in 2008 totalled 16,529 km (10,271 mi) of which 11,727 km (7,287 mi) is electrified, and on which 4,802 locomotives and railcars run. The main public operator of high-speed trains is Trenitalia, part of FSI. Higher-speed trains are divided into three categories: Frecciarossa (English: red arrow) trains operate at a maximum speed of 300 km/h on dedicated high-speed tracks; Frecciargento (English: silver arrow) trains operate at a maximum speed of 250 km/h on both high-speed and mainline tracks; and Frecciabianca (English: white arrow) trains operate on high-speed regional lines at a maximum speed of 200 km/h. Italy has 11 rail border crossings over the Alpine mountains with its neighbouring countries.

Italy is one of the countries with the most vehicles per capita, with 690 per 1000 people in 2010.[249] The national inland waterways network comprised 2,400 km (1,491 mi) of navigable rivers and channels for various types of commercial traffic in 2012.[250]

Italy's largest airline is Alitalia,[251] which serves 97 destinations (as of October 2019) and also operates a regional subsidiary under the Alitalia CityLiner brand. The country also has regional airlines (such as Air Dolomiti), low-cost carriers, and Charter and leisure carriers (including Neos, Blue Panorama Airlines and Poste Air Cargo. Major Italian cargo operators are Alitalia Cargo and Cargolux Italia.

Italy is the fifth in Europe by number of passengers by air transport, with about 148 million passengers or about 10% of the European total in 2011.[252] In 2012 there were 130 airports in Italy, including the two hubs of Malpensa International in Milan and Leonardo da Vinci International in Rome. In 2004 there were 43 major seaports, including the seaport of Genoa, the country's largest and second largest in the Mediterranean Sea. In 2005 Italy maintained a civilian air fleet of about 389,000 units and a merchant fleet of 581 ships.[248]

Italy does not invest enough to maintain its drinking water supply. The Galli Law, passed in 1993, aimed at raising the level of investment and to improve service quality by consolidating service providers, making them more efficient and increasing the level of cost recovery through tariff revenues. Despite these reforms, investment levels have declined and remain far from sufficient.[253][254][255]

Energy

Eni, with operations in 79 countries, is one of the seven "Supermajor" oil companies in the world, and one of the world's largest industrial companies.[256]

Moderate natural gas reserves, mainly in the Po Valley and offshore Adriatic Sea, have been discovered in recent years and constitute the country's most important mineral resource. Italy is one of the world's leading producers of pumice, pozzolana, and feldspar.[258] Another notable mineral resource is marble, especially the world-famous white Carrara marble from the Massa and Carrara quarries in Tuscany. Italy needs to import about 80% of its energy requirements.[259][260][261]

In the last decade, Italy has become one of the world's largest producers of renewable energy, ranking as the second largest producer in the European Union and the ninth in the world. Wind power, hydroelectricity, and geothermal power are also important sources of electricity in the country. Renewable sources account for the 27.5% of all electricity produced in Italy, with hydro alone reaching 12.6%, followed by solar at 5.7%, wind at 4.1%, bioenergy at 3.5%, and geothermal at 1.6%.[263] The rest of the national demand is covered by fossil fuels (38.2% natural gas, 13% coal, 8.4% oil) and by imports.[263]

Solar energy production alone accounted for almost 9% of the total electric production in the country in 2014, making Italy the country with the highest contribution from solar energy in the world.[262] The Montalto di Castro Photovoltaic Power Station, completed in 2010, is the largest photovoltaic power station in Italy with 85 MW. Other examples of large PV plants in Italy are San Bellino (70.6 MW), Cellino san Marco (42.7 MW) and Sant’ Alberto (34.6 MW).[264] Italy was also the first country to exploit geothermal energy to produce electricity.[162]

Italy has managed four nuclear reactors until the 1980s. However, nuclear power in Italy has been abandoned following a 1987 referendum (in the wake of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in Soviet Ukraine). The national power company Enel operates several nuclear reactors in Spain, Slovakia and France,[265][266] managing it to access nuclear power and direct involvement in design, construction, and operation of the plants without placing reactors on Italian territory.[266]

Science and technology

Galileo Galilei, recognised as the Father of modern science, physics and observational astronomy;[268]

Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of the long-distance radio transmission;[269] Enrico Fermi, creator of the first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1[270]