Economy of Bangladesh

The economy of Bangladesh is a developing market economy.[36] It's the 39th largest in the world in nominal terms, and 30th largest by purchasing power parity; it is classified among the Next Eleven emerging market middle income economies and a frontier market. In the first quarter of 2019, Bangladesh's was the world's seventh fastest growing economy with a rate of 7.3% real GDP annual growth.[37] Dhaka and Chittagong are the principal financial centers of the country, being home to the Dhaka Stock Exchange and the Chittagong Stock Exchange. The financial sector of Bangladesh is the second largest in the Indian subcontinent. Bangladesh is one of the world's fastest growing economy.

.jpg) Dhaka, the financial centre of Bangladesh | |

| Currency | Bangladeshi taka (BDT, ৳) |

|---|---|

| 1 July – 30 June | |

Trade organizations | SAFTA, SAARC, BIMSTEC, WTO, AIIB, IMF, Commonwealth of Nations, World Bank, ADB, Developing-8 |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector | |

| 5.5% (2020 est.)[5] | |

Population below poverty line | |

| 32.4 medium (2016, World Bank)[16] | |

Labor force | |

Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

Main industries | |

| External | |

| Exports |

|

Export goods | Textiles, Garments (2nd largest exporter in the world), Leather & Leather Goods, Pharmaceuticals and other Chemical products, Ceramic Products, Bicycles, Jute and Jute Goods, IT, Agricultural Products, Frozen Food (Fish and Seafood) |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports |

|

Import goods | Textiles and Textile Articles, Machinery and Mechanical Appliances, Electrical Equipment, Mineral Products, Vegetable Products, Metal & metal products, Chemicals & Allied Products, Vehicles & Aircraft |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −3.2% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[28] | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

Foreign reserves | |

.jpg)

In the decade since 2004, Bangladesh averaged a GDP growth of 6.5%, that has been largely driven by its exports of ready made garments, remittances and the domestic agricultural sector. The country has pursued export-oriented industrialisation, with its key export sectors include textiles, shipbuilding, fish and seafood, jute and leather goods. It has also developed self-sufficient industries in pharmaceuticals, steel and food processing. Bangladesh's telecommunication industry has witnessed rapid growth over the years, receiving high investment from foreign companies. Bangladesh also has substantial reserves of natural gas and is Asia's seventh largest gas producer. Offshore exploration activities are increasing in its maritime territory in the Bay of Bengal. It also has large deposits of limestone.[38] The government promotes the Digital Bangladesh scheme as part of its efforts to develop the country's growing information technology sector.

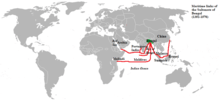

Bangladesh is strategically important for the economies of Northeast India, Nepal and Bhutan, as Bangladeshi seaports provide maritime access for these landlocked regions and countries.[39][40][41] China also views Bangladesh as a potential gateway for its landlocked southwest, including Tibet, Sichuan and Yunnan.

As of 2019, Bangladesh's GDP per capita income is estimated as per IMF data at US$5,028 (PPP) and US$1,906 (nominal).[42] Bangladesh is a member of the D-8 Organization for Economic Cooperation, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The economy faces challenges of infrastructure bottlenecks, insufficient power and gas supplies, bureaucratic corruption, natural calamities and a lack of skilled workers.

Economic history

Ancient Bengal

East Bengal—the eastern segment of Bengal—was a historically prosperous region.[43] The Ganges Delta provided advantages of a mild, almost tropical climate, fertile soil, ample water, and an abundance of fish, wildlife, and fruit.[43] The standard of living is believed to have been higher compared with other parts of South Asia.[43] As early as the thirteenth century, the region was developing as an agrarian economy.[43] Bengal was the junction of trade routes on the Southeastern Silk Road.[43]

Bengal Sultanate

The economy of the Bengal Sultanate inherited earlier aspects of the Delhi Sultanate, including mint towns, a salaried bureaucracy and the jagirdar system of land ownership. The production of silver coins inscribed with the name of the Sultan of Bengal was a mark of Bengali sovereignty.[44] Bengal was more successful in perpetuating purely silver coinage than Delhi and other contemporary Asian and European governments. There were three sources of silver. The first source was the leftover silver reserve of previous kingdoms. The second source was the tribute payments of subordinate kingdoms which were paid in silver bullion. The third source was during military campaigns when Bengali forces sacked neighboring states.[45]

The apparent vibrancy of the Bengal economy in the beginning of the 15th-century is attributed to the end of tribute payments to Delhi, which ceased after Bengali independence and stopped the outflow of wealth. Ma Huan's testimony of a flourishing shipbuilding industry was part of the evidence that Bengal enjoyed significant seaborne trade. The expansion of muslin production, sericulture and the emergence of several other crafts were indicated in Ma Huan's list of items exported from Bengal to China. Bengali shipping co-existed with Chinese shipping until the latter withdrew from the Indian Ocean in the mid-15th-century. The testimony of European travelers such as Ludovico di Varthema, Duarte Barbosa and Tomé Pires attest to the presence of a large number of wealthy Bengali merchants and shipowners in Malacca.[46] Historian Rila Mukherjee wrote that ports in Bengal may have been entrepots, importing goods and re-exporting them to China.[47]

A vigorous riverine shipbuilding tradition existed in Bengal. The shipbuilding tradition is evidenced in the sultanate's naval campaigns in the Ganges delta. The trade between Bengal and the Maldives, based on rice and cowry shells, was probably done on Arab-style baghlah ships. Chinese accounts point to Bengali ships being prominent in Southeast Asian waters. A vessel from Bengal, probably owned by the Sultan of Bengal, could accommodate three tribute missions- from Bengal, Brunei and Sumatra- and was evidently the only vessel capable of such a task. Bengali ships were the largest vessels plying in those decades in Southeast Asian waters.[48]

All large business transactions were done in terms of silver taka. Smaller purchases involved shell currency. One silver coin was worth 10,250 cowry shells. Bengal relied on shiploads of cowry shell imports from the Maldives. Due to the fertile land, there was an abundance of agricultural commodities, including bananas, jackfruits, pomegranate, sugarcane, and honey. Native crops included rice and sesame. Vegetables included ginger, mustard, onions, and garlic among others. There were four types of wines, including coconut, rice, tarry and kajang. Bengali streets were well provided with eating establishments, drinking houses and bathhouses. At least six varieties of fine muslin cloth existed. Silk fabrics were also abundant. Pearls, rugs and ghee were other important products. The finest variety of paper was made in Bengal from the bark of mulberry trees. The high quality of paper was compared with the lightweight white muslin cloth.[49]

Europeans referred to Bengal as "the richest country to trade with".[50] Bengal was the eastern pole of Islamic India. Like the Gujarat Sultanate in the western coast of India, Bengal in the east was open to the sea and accumulated profits from trade. Merchants from around the world traded in the Bay of Bengal.[51] Cotton textile exports were a unique aspect of the Bengali economy. Marco Polo noted Bengal's prominence in the textile trade.[52] In 1569, Venetian explorer Caesar Frederick wrote about how merchants from Pegu in Burma traded in silver and gold with Bengalis.[52] Overland trade routes such as the Grand Trunk Road connected Bengal to northern India, Central Asia and the Middle East.

Mughal Bengal

Under Mughal rule, Bengal operated as a centre of the worldwide muslin, silk and pearl trades.[43] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example.[53] Bengal shipped saltpeter to Europe, sold opium in Indonesia, exported raw silk to Japan and the Netherlands, and produced cotton and silk textiles for export to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[54] Real wages and living standards in 18th-century Bengal were comparable to Britain, which in turn had the highest living standards in Europe.[55]

During the Mughal era, the most important centre of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[56] Bengali agriculturalists rapidly learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal as a major silk-producing region of the world.[57] Bengal accounted for more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks imported by the Dutch from Asia, for example.[53]

Bengal also had a large shipbuilding industry. Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[58] He also assesses ship repairing as very advanced in Bengal.[58] Bengali shipbuilding was advanced compared to European shipbuilding at the time. An important innovation in shipbuilding was the introduction of a flushed deck design in Bengal rice ships, resulting in hulls that were stronger and less prone to leak than the structurally weak hulls of traditional European ships built with a stepped deck design. The British East India Company later duplicated the flushed-deck and hull designs of Bengal rice ships in the 1760s, leading to significant improvements in seaworthiness and navigation for European ships during the Industrial Revolution.[59]

British Bengal

The British East India Company, that took complete control of Bengal in 1793 by abolishing Nizamat (local rule), chose to develop Calcutta, now the capital city of West Bengal, as their commercial and administrative center for the Company-held territories in South Asia.[43] The development of East Bengal was thereafter limited to agriculture.[43] The administrative infrastructure of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries reinforced East Bengal's function as the primary agricultural producer—chiefly of rice, tea, teak, cotton, sugar cane and jute — for processors and traders from around Asia and beyond.[43]

Modern Bangladesh

After its independence from Pakistan, Bangladesh followed a socialist economy by nationalising all industries, proving to be a critical blunder undertaken by the Awami League government. Some of the same factors that had made East Bengal a prosperous region became disadvantages during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[43] As life expectancy increased, the limitations of land and the annual floods increasingly became constraints on economic growth.[43] Traditional agricultural methods became obstacles to the modernisation of agriculture.[43] Geography severely limited the development and maintenance of a modern transportation and communications system.[43]

The partition of British India and the emergence of India and Pakistan in 1947 severely disrupted the economic system. The united government of Pakistan expanded the cultivated area and some irrigation facilities, but the rural population generally became poorer between 1947 and 1971 because improvements did not keep pace with rural population increase.[43] Pakistan's five-year plans opted for a development strategy based on industrialisation, but the major share of the development budget went to West Pakistan, that is, contemporary Pakistan.[43] The lack of natural resources meant that East Pakistan was heavily dependent on imports, creating a balance of payments problem.[43] Without a substantial industrialisation programme or adequate agrarian expansion, the economy of East Pakistan steadily declined.[43] Blame was placed by various observers, but especially those in East Pakistan, on the West Pakistani leaders who not only dominated the government but also most of the fledgling industries in East Pakistan.[43]

Since Bangladesh followed a socialist economy by nationalising all industries after its independence, it underwent a slow growth of producing experienced entrepreneurs, managers, administrators, engineers, and technicians.[60] There were critical shortages of essential food grains and other staples because of wartime disruptions.[60] External markets for jute had been lost because of the instability of supply and the increasing popularity of synthetic substitutes.[60] Foreign exchange resources were minuscule, and the banking and monetary systems were unreliable.[60] Although Bangladesh had a large work force, the vast reserves of under trained and underpaid workers were largely illiterate, unskilled, and underemployed.[60] Commercially exploitable industrial resources, except for natural gas, were lacking.[60] Inflation, especially for essential consumer goods, ran between 300 and 400 percent.[60] The war of independence had crippled the transportation system.[60] Hundreds of road and railroad bridges had been destroyed or damaged, and rolling stock was inadequate and in poor repair.[60] The new country was still recovering from a severe cyclone that hit the area in 1970 and caused 250,000 deaths.[60] India came forward immediately with critically measured economic assistance in the first months after Bangladesh achieved independence from Pakistan.[60] Between December 1971 and January 1972, India committed US$232 million in aid to Bangladesh from the politico-economic aid India received from the US and USSR. Official amount of disbursement yet undisclosed.[60]

After 1975, Bangladeshi leaders began to turn their attention to developing new industrial capacity and rehabilitating its economy.[61] The static economic model adopted by these early leaders, however—including the nationalisation of much of the industrial sector—resulted in inefficiency and economic stagnation.[61] Beginning in late 1975, the government gradually gave greater scope to private sector participation in the economy, a pattern that has continued.[61] Many state-owned enterprises have been privatised, like banking, telecommunication, aviation, media, and jute.[61] Inefficiency in the public sector has been rising however at a gradual pace; external resistance to developing the country's richest natural resources is mounting; and power sectors including infrastructure have all contributed to slowing economic growth.[61]

In the mid-1980s, there were encouraging signs of progress.[61] Economic policies aimed at encouraging private enterprise and investment, privatising public industries, reinstating budgetary discipline, and liberalising the import regime were accelerated.[61] From 1991 to 1993, the government successfully followed an enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but failed to follow through on reforms in large part because of preoccupation with the government's domestic political troubles.[61] In the late 1990s the government's economic policies became more entrenched, and some gains were lost, which was highlighted by a precipitous drop in foreign direct investment in 2000 and 2001.[61] In June 2003 the IMF approved 3-year, $490-million plan as part of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) for Bangladesh that aimed to support the government's economic reform programme up to 2006.[61] Seventy million dollars was made available immediately.[61] In the same vein the World Bank approved $536 million in interest-free loans.[61] The economy saw continuous real GDP growth of at least 5% since 2003. In 2010, Government of India extended a line of credit worth $1 billion to counterbalance China's close relationship with Bangladesh.

Bangladesh historically has run a large trade deficit, financed largely through aid receipts and remittances from workers overseas.[61] Foreign reserves dropped markedly in 2001 but stabilised in the US$3 to US$4 billion range (or about 3 months' import cover).[61] In January 2007, reserves stood at $3.74 billion, and then increased to $5.8 billion by January 2008, in November 2009 it surpassed $10.0 billion, and as of April 2011 it surpassed the US$12 billion according to the Bank of Bangladesh, the central bank.[61] The dependence on foreign aid and imports has also decreased gradually since the early 1990s.[62] According to Bangladesh bank the reserve is $30 billion in August 2016

In last decade, poverty dropped by around one third with significant improvement in human development index, literacy, life expectancy and per capita food consumption. With economy growing close to 6% per year, more than 15 million people have moved out of poverty since 1992.[63]

Macro-economic trend

This is a chart of trend of gross domestic product of Bangladesh at market prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund with figures in millions of Bangladeshi Taka. However, this reflects only the formal sector of the economy.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product (Million Taka) | US Dollar Exchange | Inflation Index (2000=100) | Per Capita Income (as % of USA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 250,300 | 16.10 Taka | 20 | 1.79 |

| 1985 | 597,318 | 31.00 Taka | 36 | 1.19 |

| 1990 | 1,054,234 | 35.79 Taka | 58 | 1.16 |

| 1995 | 1,594,210 | 40.27 Taka | 78 | 1.12 |

| 2000 | 2,453,160 | 52.14 Taka | 100 | 0.97 |

| 2005 | 3,913,334 | 63.92 Taka | 126 | 0.95 |

| 2008 | 5,003,438 | 68.65 Taka | 147 | |

| 2015 | 17,295,665 | 78.15 Taka. | 196 | 2.48 |

| 2019 | 26,604,164 | 84.55 Taka. | 2.91 |

Mean wages were $0.58 per man-hour in 2009.

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2019. Inflation below 5% is in green.[64][65]

| Year | GDP (in bn. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment Rate

(in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

Total Investment

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 41.2 | 500 | n/a | n/a | |||

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1982 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1983 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1984 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1985 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1986 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1987 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1988 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1989 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1990 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1991 | 2.20 % | n/a | |||||

| 1992 | n/a | ||||||

| 1993 | n/a | ||||||

| 1994 | n/a | ||||||

| 1995 | n/a | ||||||

| 1996 | n/a | ||||||

| 1997 | n/a | ||||||

| 1998 | n/a | ||||||

| 1999 | n/a | ||||||

| 2000 | n/a | ||||||

| 2001 | n/a | ||||||

| 2002 | n/a | ||||||

| 2003 | 44.3 % | ||||||

| 2004 | |||||||

| 2005 | |||||||

| 2006 | |||||||

| 2007 | |||||||

| 2008 | |||||||

| 2009 | |||||||

| 2010 | |||||||

| 2011 | |||||||

| 2012 | |||||||

| 2013 | |||||||

| 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | |||||||

| 2016 | |||||||

| 2017 | |||||||

| 2018 | |||||||

| 2019 |

Economic sectors

| Sectoral Shares of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Bangladesh | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) Agriculture | 14.77 | 14.17 | 13.82 | 13.32 |

| Agriculture and forestry | 11.55 | 10.98 | 10.68 | 10.25 |

| Crops & horticulture | 8.15 | 7.69 | 7.48 | 7.12 |

| Animal Farmings | 2.01 | 1.93 | 1.86 | 1.79 |

| Forest and related services | 1.39 | 1.37 | 1.34 | 1.35 |

| Fishing | 3.22 | 3.19 | 3.14 | 3.07 |

| B) Industry | 28.77 | 29.32 | 30.17 | 31.15 |

| Mining and quarrying | 1.73 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 1.82 |

| Natural gas and crude petroleum | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.58 |

| Other mining & coal | 1.08 | 1.18 | 1.2 | 1.24 |

| Manufacturing | 17.91 | 18.28 | 18.99 | 19.89 |

| Large & medium scale | 14.58 | 14.93 | 15.63 | 16.37 |

| Small scale | 3.34 | 3.35 | 3.36 | 3.52 |

| Electricity, gas and water supply | 1.45 | 1.4 | 1.38 | 1.33 |

| Electricity | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.04 |

| Gas | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Water | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Construction | 7.67 | 7.81 | 7.98 | 8.12 |

| C) Service | 56.46 | 56.5 | 56 | 55.53 |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of

motor vehicles, motorcycles and personal and household goods |

13.01 | 13.05 | 13.15 | 13.34 |

| Hotel and restaurants | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| Transport, storage & communication | 10.27 | 10 | 9.61 | 9.34 |

| Land transport | 7.76 | 7.64 | 7.38 | 7.22 |

| Water transport | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| Air transport | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Support transport services, storage | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| Post and Tele communications | 1.32 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 1.1 |

| Financial intermediations | 3.86 | 3.91 | 3.93 | 3.89 |

| Monetary intermediation (banks) | 3.27 | 3.34 | 3.37 | 3.35 |

| Insurance | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Other financial auxiliaries | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Real estate, renting and business activities | 7.51 | 7.73 | 7.82 | 7.87 |

| Public administration and defence | 4.05 | 4.19 | 4.24 | 4.09 |

| Education | 2.82 | 3.04 | 3.03 | 3.02 |

| Health and social works | 2.11 | 2.08 | 2.07 | 2.15 |

| Community, social and personal services | 11.79 | 11.46 | 11.11 | 10.78 |

| Percentage of sectoral shares of GDP of Bangladesh[66] | ||||

Agriculture

Most Bangladeshis earn their living from agriculture.[61] Although rice and jute are the primary crops, maize and vegetables are assuming greater importance.[61] Due to the expansion of irrigation networks, some wheat producers have switched to cultivation of maize which is used mostly as poultry feed.[61] Tea is grown in the northeast.[61] Because of Bangladesh's fertile soil and normally ample water supply, rice can be grown and harvested three times a year in many areas.[61] Due to a number of factors, Bangladesh's labour-intensive agriculture has achieved steady increases in food grain production despite the often unfavourable weather conditions.[61] These include better flood control and irrigation, a generally more efficient use of fertilisers, and the establishment of better distribution and rural credit networks.[61] With 28.8 million metric tons produced in 2005–2006 (July–June), rice is Bangladesh's principal crop.[61] By comparison, wheat output in 2005–2006 was 9 million metric tons.[61] Population pressure continues to place a severe burden on productive capacity, creating a food deficit, especially of wheat.[61] Foreign assistance and commercial imports fill the gap,[61] but seasonal hunger ("monga") remains a problem.[67] Underemployment remains a serious problem, and a growing concern for Bangladesh's agricultural sector will be its ability to absorb additional manpower.[61] Finding alternative sources of employment will continue to be a daunting problem for future governments, particularly with the increasing numbers of landless peasants who already account for about half the rural labour force.[61] Due to farmers' vulnerability to various risks, Bangladesh's poorest face numerous potential limitations on their ability to enhance agriculture production and their livelihoods. These include an actual and perceived risk to investing in new agricultural technologies and activities (despite their potential to increase income), a vulnerability to shocks and stresses and a limited ability to mitigate or cope with these and limited access to market information.[67]

Manufacturing and industry

Many new jobs – mostly for women – have been created by the country's dynamic private ready-made garment industry, which grew at double-digit rates through most of the 1990s.[61] By the late 1990s, about 1.5 million people, mostly women, were employed in the garments sector as well as Leather products specially Footwear (Shoe manufacturing unit). During 2001–2002, export earnings from ready-made garments reached $3,125 million, representing 52% of Bangladesh's total exports. Bangladesh has overtaken India in apparel exports in 2009, its exports stood at 2.66 billion US dollar, ahead of India's 2.27 billion US dollar and in 2014 the export rose to $3.12 billion every month. At the fiscal year 2018, Bangladesh has been able to garner US$36.67 billion export earnings by exporting manufactured goods, of which, 83.49 percent has come from the apparel manufacturing sector.[68]

Eastern Bengal was known for its fine muslin and silk fabric before the British period. The dyes, yarn, and cloth were the envy of much of the premodern world. Bengali muslin, silk, and brocade were worn by the aristocracy of Asia and Europe. The introduction of machine-made textiles from England in the late eighteenth century spelled doom for the costly and time-consuming hand loom process. Cotton growing died out in East Bengal, and the textile industry became dependent on imported yarn. Those who had earned their living in the textile industry were forced to rely more completely on farming. Only the smallest vestiges of a once-thriving cottage industry survived.[69]

Other industries which have shown very strong growth include the pharmaceutical industry,[70] shipbuilding industry,[71] information technology,[72] leather industry,[73] steel industry,[74][75] and light engineering industry.[76][77]

Bangladesh's textile industry, which includes knitwear and ready-made garments (RMG) along with specialised textile products, is the nation's number one export earner, accounting for $21.5 billion in 2013 – 80% of Bangladesh's total exports of $27 billion.[78] Bangladesh is 2nd in world textile exports, behind China, which exported $120.1 billion worth of textiles in 2009. The industry employs nearly 3.5 million workers. Current exports have doubled since 2004. Wages in Bangladesh's textile industry were the lowest in the world as of 2010. The country was considered the most formidable rival to China where wages were rapidly rising and currency was appreciating.[79][80] As of 2012 wages remained low for the 3 million people employed in the industry, but labour unrest was increasing despite vigorous government action to enforce labour peace. Owners of textile firms and their political allies were a powerful political influence in Bangladesh.[81] The urban garment industry has created more than one million formal sector jobs for women, contributing to the high female labour participation in Bangladesh.[82] While it can be argued that women working in the garment industry are subjected to unsafe labour conditions and low wages, Dina M. Siddiqi argues that even though conditions in Bangladesh garment factories "are by no means ideal," they still give women in Bangladesh the opportunity to earn their own wages.[83] As evidence she points to the fear created by the passage of the 1993 Harkins Bill (Child Labor Deterrence Bill), which caused factory owners to dismiss "an estimated 50,000 children, many of whom helped support their families, forcing them into a completely unregulated informal sector, in lower-paying and much less secure occupations such as brick-breaking, domestic service and rickshaw pulling."[83]

Even though the working conditions in garment factories are not ideal, they tend to financially be more reliable than other occupations and, "enhance women’s economic capabilities to spend, save and invest their incomes."[84] Both married and unmarried women send money back to their families as remittances, but these earned wages have more than just economic benefits. Many women in the garment industry are marrying later, have lower fertility rates, and attain higher levels of education, then women employed elsewhere.[84]

After massive labour unrest in 2006[85] the government formed a Minimum Wage Board including business[86] and worker representatives which in 2006 set a minimum wage equivalent to 1,662.50 taka, $24 a month, up from Tk950. In 2010, following widespread labour protests involving 60,000 workers in June 2010,[87][88][89] a controversial proposal was being considered by the Board which would raise the monthly minimum to the equivalent of $50 a month, still far below worker demands of 5,000 taka, $72, for entry level wages, but unacceptably high according to textile manufacturers who are asking for a wage below $30.[80][90] On 28 July 2010 it was announced that the minimum entry level wage would be increased to 3,000 taka, about $43.[91]

The government also seems to believe some change is necessary. On 21 September 2006 then ex-Prime Minister Khaleda Zia called on textile firms to ensure the safety of workers by complying with international labour law at a speech inaugurating the Bangladesh Apparel & Textile Exposition (BATEXPO).

Many Western multinationals use labour in Bangladesh, which is one of the cheapest in the world: 30 euros per month compared to 150 or 200 in China. Four days is enough for the CEO of one of the top five global textile brands to earn what a Bangladeshi garment worker will earn in her lifetime. In April 2013, at least 1,135 textile workers died in the collapse of their factory. Other fatal accidents due to unsanitary factories have affected Bangladesh: in 2005 a factory collapsed and caused the death of 64 people. In 2006, a series of fires killed 85 people and injured 207 others. In 2010, some 30 people died of asphyxiation and burns in two serious fires.[92]

In 2006, tens of thousands of workers mobilized in one of the country's largest strike movements, affecting almost all of the 4,000 factories. The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) uses police forces to crack down. Three workers were killed, hundreds more were wounded by bullets, or imprisoned. In 2010, after a new strike movement, nearly 1,000 people were injured among workers as a result of the repression.[92]

Shipbuilding and ship breaking

Shipbuilding is a growing industry in Bangladesh with great potential.[93][94] Due to the potential of shipbuilding in Bangladesh, the country has been compared to countries like China, Japan and South Korea.[95] Referring to the growing amount of export deals secured by the shipbuilding companies as well as the low cost labour available in the country, experts suggest that Bangladesh could emerge as a major competitor in the global market of small to medium ocean-going vessels.[96]

Bangladesh also has the world's largest ship breaking industry which employs over 200,000 Bangladeshis and accounts for half of all the steel in Bangladesh.[97] Chittagong Ship Breaking Yard is the world's second-largest ship breaking area.

Khulna Shipyard Limited (KSY) with over five decades of reputation has been leading the Bangladesh Shipbuilding industry and had built a wide spectrum of ships for domestic and international clients. KSY built ships for Bangladesh Navy, Bangladesh Army and Bangladesh Coast Guard under the contract of ministry of defence.

Finance

Until the 1980s, the financial sector of Bangladesh was dominated by state-owned banks.[98] With the grand-scale reform made in finance, private commercial banks were established through privatisation. The next finance sector reform programme was launched from 2000 to 2006 with focus on the development of financial institutions and adoption of risk-based regulations and supervision by Bangladesh Bank. As of date, the banking sector consisted of 4 SCBs, 4 government-owned specialized banks dealing in development financing, 39 private commercial banks, and 9 foreign commercial banks.

Tourism

Information and Communication Technology

Bangladesh's information technology sector is growing example of what can be achieved after the current government's relentless effort to create a skilled workforce in ICT sector. The ICT workforce consisted of private sector and freelance skilled ICT workforce. The ICT sector also contributed to Bangladesh's economic growth. The ICT adviser to the prime minister, Sajeeb Wazed Joy is hopeful that Bangladesh will become a major player in the ICT sector in the future.[99] In the last 3 years, Bangladesh has seen a tremendous growth in the ICT sector. Bangladesh is a market of 160 million people with vast consumer spending around mobile phones, telco and internet. Bangladesh has 80 million[100] internet users, an estimated 9% growth in internet use by June 2017 powered by mobile internet. Bangladesh currently has an active 23 million[101] Facebook users. Bangladesh currently has 143.1 million mobile phone customers.[100] Bangladesh has exported $800 million[102] worth of software, games, outsourcing and services to European countries, the United States, Canada, Russia and India by 30 June 2017. The Junior Minister for ICT division of the Ministry of Post, Telecommunications and Information Technology said that Bangladesh aims to raise its export earnings from the information and communications technology (ICT) sector to $5 billion by 2021.[103]

Investment

The stock market capitalisation of the Dhaka Stock Exchange in Bangladesh crossed $10 billion in November 2007 and the $30 billion mark in 2009, and US$50 billion in August 2010.[104] Bangladesh had the best performing stock market in Asia during the recent global recession between 2007 and 2010, due to relatively low correlations with developed country stock markets.[105]

Major investment in real estate by domestic and foreign-resident Bangladeshis has led to a massive building boom in Dhaka and Chittagong.

Recent (2011) trends for investing in Bangladesh as Saudi Arabia trying to secure public and private investment in oil and gas, power and transportation projects, United Arab Emirates (UAE) is keen to invest in growing shipbuilding industry in Bangladesh encouraged by comparative cost advantage, Tata, an India-based leading industrial multinational to invest Taka 1500 crore to set up an automobile industry in Bangladesh, World Bank to invest in rural roads improving quality of live, the Rwandan entrepreneurs are keen to invest in Bangladesh's pharmaceuticals sector considering its potentiality in international market, Samsung sought to lease 500 industrial plots from the export zones authority to set up an electronics hub in Bangladesh with an investment of US$1.25 billion, National Board of Revenue (NBR) is set to withdraw tax rebate facilities on investment in the capital market by individual taxpayers from the fiscal 2011–12.[106] In 2011, Japan Bank for International Cooperation ranked Bangladesh as the 15th best investment destination for foreign investors.[107]

2010–11 market crash

The bullish capital market turned bearish during 2010, with the exchange losing 1,800 points between December 2010 and January 2011.[108] Millions of investors have been rendered bankrupt as a result of the market crash. The crash is believed to be caused artificially to benefit a handful of players at the expense of the big players.[108]

Companies

The list includes ten largest Bangladeshi companies by trading value (millions in BDT) in 2018.[109][110]

| Rank | Company | Trading name at Dhaka Stock Exchange | Headquarters | Industry | Trading Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Square Pharmaceuticals Limited | SQURPHARMA | Dhaka | Pharmaceuticals | 449.8880 |

| 2 | Dragon Sweater and Spinning Limited | DSSL | Dhaka | Apparel | 129.4030 |

| 3 | Ifad Autos Limited | IFADAUTOS | Dhaka | Automotive | 117.5370 |

| 4 | Grameenphone Private Limited | GP | Dhaka | Telecommunications | 106.8660 |

| 5 | Bangladesh Thai Aluminium Ltd | BDTHAI | Dhaka | Manufacturing | 99.7690 |

| 6 | City Bank Limited | CITYBANK | Dhaka | Banking | 78.6010 |

| 7 | Golden Harvest | GHAIL | Dhaka | Agriculture | 76.6710 |

| 8 | IPDC Finance Limited | IPDC | Dhaka | Financial Services | 67.0430 |

| 9 | Olympic industries limited | OLYMPIC | Dhaka | Manufacturing | 60.5570 |

| 10 | Shahjalal Islami Bank Limited | SHAHJABANK | Dhaka | Banking | 53.1710 |

Composition of economic sectors

.jpg)

The Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) has predicted textile exports will rise from US$7.90 billion earned in 2005–06 to US$15 billion by 2011. In part this optimism stems from how well the sector has fared since the end of textile and clothing quotas, under the Multifibre Agreement, in early 2005.

According to a United Nations Development Programme report "Sewing Thoughts: How to Realize Human Development Gains in the Post-Quota World" Bangladesh has been able to offset a decline in European sales by cultivating new markets in the United States.[111]

"[In 2005] we had tremendous growth. The quota-free textile regime has proved to be a big boost for our factories," said BGMEA president S.M. Fazlul Hoque told reporters, after the sector's 24 per cent growth rate was revealed.[112]

The Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA) president Md Fazlul Hoque has also struck an optimistic tone. In an interview with United News Bangladesh he lauded the blistering growth rate, saying "The quality of our products and its competitiveness in terms of prices helped the sector achieve such... tremendous success."

Knitwear posted the strongest growth of all textile products in 2005–06, surging 35.38 per cent to US$2.82 billion. On the downside however, the sector's strong growth came amid sharp falls in prices for textile products on the world market, with growth subsequently dependent upon large increases in volume.

Bangladesh's quest to boost the quantity of textile trade was also helped by US and EU caps on Chinese textiles. The US cap restricts growth in imports of Chinese textiles to 12.5 per cent next year and between 15 and 16 per cent in 2008. The EU deal similarly manages import growth until 2008.

Bangladesh may continue to benefit from these restrictions over the next two years, however a climate of falling global textile prices forces wage rates the centre of the nation's efforts to increase market share.

They offer a range of incentives to potential investors including 10-year tax holidays, duty-free import of capital goods, raw materials and building materials, exemptions on income tax on salaries paid to foreign nationals for three years and dividend tax exemptions for the period of the tax holiday.

All goods produced in the zones are able to be exported duty-free, in addition to which Bangladesh benefits from the Generalised System of Preferences in US, European and Japanese markets and is also endowed with Most Favoured Nation status from the United States.

Furthermore, Bangladesh imposes no ceiling on investment in the EPZs and allows full repatriation of profits.

The formation of labour unions within the EPZs is prohibited as are strikes.[113]

Bangladesh has been a world leader in its efforts to end the use of child labour in garment factories. On 4 July 1995, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, International Labour Organization, and UNICEF signed a memorandum of understanding on the elimination of child labour in the garment sector. Implementation of this pioneering agreement began in fall 1995, and by the end of 1999, child labour in the garment trade virtually had been eliminated.[114] The labour-intensive process of ship breaking for scrap has developed to the point where it now meets most of Bangladesh's domestic steel needs. Other industries include sugar, tea, leather goods, newsprint, pharmaceutical, and fertilizer production.

The Bangladesh government continues to court foreign investment, something it has done fairly successfully in private power generation and gas exploration and production, as well as in other sectors such as cellular telephony, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. In 1989, the same year it signed a bilateral investment treaty with the United States, it established a Board of Investment to simplify approval and start-up procedures for foreign investors, although in practice the board has done little to increase investment. The government created the Bangladesh Export Processing Zone Authority to manage the various export processing zones. The agency currently manages EPZs in Adamjee, Chittagong, Comilla, Dhaka, Ishwardi, Karnaphuli, Mongla, and Uttara. An EPZ has also been proposed for Sylhet.[115] The government has given the private sector permission to build and operate competing EPZs-initial construction on a Korean EPZ started in 1999. In June 1999, the AFL-CIO petitioned the U.S. Government to deny Bangladesh access to U.S. markets under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), citing the country's failure to meet promises made in 1992 to allow freedom of association in EPZs.

International trade

Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on almost all sectors of the economy, inter alia, most notably, it has caused a reduction of exports by 16.93 percent, and imports by 17 percent in the FY2019-20.[116]

.svg.png)

In 2015, the top exports of Bangladesh are Non-Knit Men's Suits ($5.6B), Knit T-shirts ($5.28B), Knit Sweaters ($4.12B), Non-Knit Women's Suits ($3.66B) and Non-Knit Men's Shirts ($2.52B).[117] In 2015, the top imports of Bangladesh are Heavy Pure Woven Cotton ($1.33B), Refined Petroleum ($1.25B), Light Pure Woven Cotton ($1.12B), Raw Cotton ($1.01B) and Wheat ($900M).[117]

In 2015, the top export destinations of Bangladesh are the United States ($6.19B), Germany ($5.17B), the United Kingdom ($3.53B), France ($2.37B) and Spain ($2.29B).[117] In 2015, the top import origins are China ($13.9B), India ($5.51B), Singapore ($2.22B), Hong Kong ($1.47B) and Japan ($1.36B).[117]

Bangladeshi women and the economy

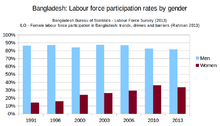

As of 2014, female participation in the labour force is 58% as per World Bank data,[118] and male participation at 82%.

A 2007 World Bank report stated that the areas in which women's work force participation have increased the most are in the fields of agriculture, education and health and social work.[82] Over three-quarters of women in the labour force work in the agricultural sector. On the other hand, the International Labour Organization reports that women's workforce participation has only increased in the professional and administrative areas between 2000 and 2005, demonstrating women's increased participation in sectors that require higher education. Employment and labour force participation data from the World Bank, the UN, and the ILO vary and often under report on women's work due to unpaid labour and informal sector jobs.[119] Though these fields are mostly paid, women experience very different work conditions than men, including wage differences and work benefits. Women's wages are significantly lower than men's wages for the same job with women being paid as much as 60–75 percent less than what men make.[120]

One example of action that is being taken to improve female conditions in the work force is Non-Governmental Organisations. These NGOs encourage women to rely on their own self-savings, rather than external funds provide women with increased decision-making and participation within the family and society.[121] However, some NGOs that address microeconomic issues among individual families fail to deal with broader macroeconomic issues that prevent women's complete autonomy and advancement.[121]

Historical statistics

Bangladesh has made significant strides in its economic sector performance since independence in 1971. Although the economy has improved vastly in the 1990s, Bangladesh still suffers in the area of foreign trade in South Asian region. Despite major impediments to growth like the inefficiency of state-owned enterprises, a rapidly growing labour force that cannot be absorbed by agriculture, inadequate power supplies,[122] and slow implementation of economic reforms, Bangladesh has made some headway improving the climate for foreign investors and liberalising the capital markets; for example, it has negotiated with foreign firms for oil and gas exploration, better countrywide distribution of cooking gas, and the construction of natural gas pipelines and power stations. Progress on other economic reforms has been halting because of opposition from the bureaucracy, public sector unions, and other vested interest groups.

The especially severe floods of 1998 increased the flow of international aid. So far the global financial crisis has not had a major impact on the economy.[123] Foreign aid has seen a gradual decline over the last few decades but economists see this as a good sign for self-reliance.[124] There has been a dramatic growth in exports and remittance inflow which has helped the economy to expand at a steady rate.[125][126]

Bangladesh has been on the list of UN Least Developed Countries (LDC) since 1975. Bangladesh met the requirements to be recognised as a developing country in March, 2018.[127] Bangladesh's Gross National Income (GNI) $1,724 per capita, the Human Assets Index (HAI) 72 and the Economic Vulnerability (EVI) Index 25.2.[127][128]

Gross export and import

| Fiscal Year | Total Export

(in bn. US$) |

Total Import

(in bn. US$) |

Foreign Remittance Earnings

(in bn. US$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–2008 | |||

| 2008–2009 | |||

| 2009–2010 | |||

| 2010–2011 | |||

| 2011–2012 | |||

| 2012–2013 | |||

| 2013–2014 | |||

| 2014–2015 | |||

| 2015-2016 | |||

| 2016-2017 | |||

| 2017-2018 | |||

| 2018-2019 |

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "SOUTH ASIA :: BANGLADESH". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Global Economic Prospects, June 2020". openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 98. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Global Economic Prospects, June 2020". https://www.thedailystar.net/. Bangladesh Government. p. 98. Retrieved 11 August 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - Kabir, FHM Humayan (8 June 2020). "Budget for FY '21: Govt set to target $2,326 per-capita income". The Financial Express. Dhaka.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Bangladesh (Final) 2017-18 (PDF) (Report) (Final ed.). Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). 18 September 2018. p. 5. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Industries helping to achieve record GDP growth". Dhaka Tribune. 5 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Poverty rate lowers to 20.5pc in 2018-19". New Age. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Freeing the poor from poverty and hunger". The Financial Express. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "South Asia Economic Focus, Spring 2020 : The Cursed Blessing of Public Banks". openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 89. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Select by country: Bangladesh". World Poverty Clock.

- Ferreira, Francisco (4 October 2015). "The international poverty line has just been raised to $1.90 a day, but global poverty is basically unchanged. How is that even possible?". Let's Talk Development. The World Bank.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". World Bank. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Labor force, total - Bangladesh". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate)". World Bank. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Report on Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2016-17 (PDF). BBS. January 2018. p. 173. ISBN 978-984-519-110-4. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Report on Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2016-17 (PDF). BBS. January 2018. p. 70. ISBN 978-984-519-110-4. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Rankings: South Asia". Doing Business. The World Bank.

- "Bangladesh ranks 2nd in WTO export growth index". Prothom-Alo. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "Report: Cumulative Region-wise Data". EPB. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Trade deficit falls by 14.76% in FY19". 19 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "Trade Profiles: Bangladesh". WTO. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Bangladesh". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Akter, Doulot (2 July 2018). "NBR misses revised target by 9.0pc, original 17.0pc". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Parliament passes budget for 2020-21 FY". The daily star. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Karim, Naim Ul (7 June 2018). "Roundup: Bangladesh unveils about 55.31 bln USD national budget". xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- "Moody's affirms Bangladesh's Ba3 rating, maintains stable outlook". Moody's. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Fitch – Complete Sovereign Rating History". Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- Harmachi, Abdur Rahim (2 July 2020). "আরেকটি মাইলফলক অতিক্রম করতে যাচ্ছে রিজার্ভ". www.jugantor.com. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Riaz, Ali; Rahman, Mohammad Sajjadur (2016). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Bangladesh. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-317-30876-8.

- "Real GDP Growth: Annual Percent Change". imf.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Largest limestone reserve discovered". The Daily Star. 4 June 2012.

- Rahmatullah, M (20 March 2013). "Regional Transport Connectivity: Its current state". The Daily Star.

- Chowdhury, Kamran Reza (19 May 2013). "Mongla seaport to get railway link in 4 years". Dhaka Tribune.

- "Sub-regional connectivity in South Asia: Prospects and challenges". The Financial Express. 13 July 2013.

- "Bangladesh's per capita income $1,314". The Daily Star. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Lawrence B. Lesser. "Historical Perspective". A Country Study: Bangladesh (James Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1988). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.About the Country Studies / Area Handbooks Program: Country Studies – Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- "Bengal". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018.

- John H Munro (6 October 2015). Money in the Pre-Industrial World: Bullion, Debasements and Coin Substitutes. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-317-32191-0.

- Irfan Habib (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. p. 185. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1.

- Rila Mukherjee (2011). Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism. Primus Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7.

some of them [items exported from Bengal to China] were probably re-exports. The Bengal ports possibly functioned as entrepots in Western routes in the trade with China.

- Tapan Raychaudhuri; Irfan Habib, eds. (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India. Volume I, c.1200-c.1750. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- María Dolores Elizalde; Wang Jianlang (6 November 2017). China's Development from a Global Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 57–70. ISBN 978-1-5275-0417-2.

- J. N. Nanda (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- Claude Markovits, ed. (2004) [First published in 1994 as Histoire de L'Inde Moderne]. A History of Modern India, 1480-1950. Anthem Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

- Sushil Chaudhury (2012). "Trade and Commerce". In Sirajul Islam and Ahmed A. Jamal (ed.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Prakash, Om (2006). "Empire, Mughal". In John J. McCusker (ed.). History of World Trade Since 1450. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 237–240. Retrieved 3 August 2017 – via Gale in Context: World History.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780521566032.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011). Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–45. ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0.

- Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780520205079.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780521566032.

- Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- "Technological Dynamism in a Stagnant Sector: Safety at Sea during the Early Industrial Revolution" (PDF).

- Lawrence B. Lesser. "Economic Reconstruction after Independence". A Country Study: Bangladesh (James Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1988). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.About the Country Studies / Area Handbooks Program: Country Studies – Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- "Background Note: Bangladesh". Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs. March 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2008. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Politics and managing the national economy: How to achieve sustainable economic growth". The Financial Express. Dhaka. 22 May 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "World Bank: Bangladesh Country Overview".

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Economy of Bangladesh". 🔴 bdnewsnet.com. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Rebecca Holmes, John Farrington, Taifur Rahman and Rachel Slater (2008) Extreme poverty in Bangladesh: Protecting and promoting rural livelihoods London: Overseas Development Institute "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hossain, Md. Sajib; Kabir, Rashedul; Latifee, Enamul Hafiz. "Export Competitiveness of Bangladesh Readymade Garments Sector: Challenges and Prospects". International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science. 8 (3): 51. doi:10.20525/ijrbs.v8i3.205.

- Karim, Abdul (2012). "Muslin". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Bangladesh to emerge as 'power house' in drug manufacturing". The Financial Express. Dhaka. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Shipbuilding prospects shine bright". The Daily Star. 3 March 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh IT industry going global". The Daily Star. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Leather industry aims to cross $1b exports". The Daily Star. 18 January 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "The prince of steel". The Daily Star. 19 December 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh can tap potential in electronics, ICT sectors". Daily Sun. 20 April 2013. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Light engineering in limelight". The Daily Star. 8 January 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh looks to diversify". Dhaka Courier. 21 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh Sept exports soar 36 pct on garment sales". Reuters. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- "China textile cos may go bankrupt". The Financial Express. New Delhi. 13 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Bajaj, Vikas (16 July 2010). "Bangladesh, With Low Pay, Moves In on China". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Yardley, Jim (23 August 2012). "Export Powerhouse Feels Pangs of Labor Strife". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- "Whispers to Voices: Gender and Social Transformation in Bangladesh" (PDF). Bangladesh Development Series, Paper No. 22. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. p. 57.

- Siddiqi, Dina (2009). "Do Bangladeshi Factory Workers Need Saving?: Sisterhood in the Post-Sweatshop Era". Feminist Review. Palgrave Macmillan. 91 (1): 154–174. doi:10.1057/fr.2008.55.

- Khosla, Nidhi (2009). "The Ready-made Garments Industry in Bangladesh: A Means to Reducing Gender-based Social Exclusion of Women?". Journal of International Women's Studies. 11 (1): 289–303.

- "One dead after Bangladesh protest". BBC News. 23 May 2006.

- "Bangladesh world's 2nd most pro-free market country". Dhaka Tribune. 1 November 2014.

- "Full blown RMG violence at Ashulia". The Financial Express. Dhaka. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Bangladesh garment workers reject 25 dollar minimum wage, to strike on Oct. 10". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- "All quiet on Ashulia front Case filed against 60,000 unidentified factory workers". The New Nation. Dhaka. 24 June 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- "Bangladesh garment industry edging closer to wage deal?". just-style.com. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Bajaj, Vikas (28 July 2010). "Bangladesh Garment Workers Awarded Higher Pay". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- https://www.bastamag.net/Au-Bangladesh-une-ouvriere-du

- "Shipbuilders seek working capital for 10 years". Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS). 9 May 2013.

- "Mozena sees bright future of shipbuilding industry". The Independent. Dhaka. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- "Bangladesh shipbuilding goes for export growth". BBC News. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "Experts for promoting shipbuilding business", The Bangladesh Today, June 2013

- "Ship breaking in Bangladesh: Hard to break up". The Economist. 27 October 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Aaron Batten, Poullang Doung, Enerelt Enkhbold, Gemma Estrada, Jan Hansen, George Luarsabishvili, Md. Goland Mortaza, and Donghyun Park, 2015. The Financial Systems of Financially Less Developed Asian Economies: Key Features and Reform Priorities. ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 450

- "ICT sector in Bangladesh". theindependentbd. 30 July 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Over half of Bangladesh's 160 million population now use internet: BTRC". benews24. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "BRTC counts 73.73 million internet users". benews24. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "ICT export earnings rise by 25% in FY'17". dhakatribune. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "ICT export fetches $800m in 2017". The Daily Star. 17 November 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Macroeconomic situation" (PDF). Ministry of Finance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh plans mass privatisations to cool stock market". Daily FT. Colombo, Sri Lanka. Agence France-Presse. 14 November 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- "Samsung wants plots in Bangladesh EPZs to set up electronics hub". Priyo. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh 15th best investment destination". The Daily Star. 7 January 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Probe panel finds massive manipulation at Bangla stock market". The Economic Times. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- http://www.dsebd.org/top_20_share.php

- "Pharma firms take to contract manufacturing". The Daily Star. 7 April 2008.

- "Sewing Thoughts: How to Realise Human Development Gains in the Post-Quota World" (PDF). United Nation Development Programme. April 2006.

- "BD eyes $15bn textile exports by 2011". Dawn. Karachi. 3 September 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007.

- "Bangladesh Export Promotion Bureau". Bangladesh Export Promotion Bureau. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- "addressing child labour in the Bangladesh garment industry 199". ILO. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Export promotion Zone in the Sylhet region of Bangladesh demanded". Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS). 29 October 2002. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007.

- Latifee, Enamul Hafiz; Hossian, Md Sajib (10 August 2020). "Corona crisis can be a best opportunity to start own business". The Daily Observer- (Volume 09, No.: 213). Observer Ltd. Globe Printers. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Bangladesh". MIT. 29 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "World Bank". World Bank. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Mahmud, Simeen; Sakiba Tasnee (2011). The Under Reporting of Women's Economic Activity In Bangladesh: An Examination of Official Statistics (Report). BRAC Development Institute.

- Hossain, Mohammad; Clement A. Tisdell (2005). "Closing the Gender Gap in Bangladesh: Inequality in Education, Employment and Earnings" (PDF). International Journal of Social Economics. 32 (5): 439–453. doi:10.1108/03068290510591281.

- Kabeer, Naila; Muhmud Simeen; Jairo Isaza (2012). "NGOs and the Political Empowerment of Poor People in Rural Bangladesh: Cultivating the Habits of Democracy?". World Development. 40 (10): 2044–2062. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.011.

- "Bangladesh Power Demand". Bangladesh Power Development Board. June 2012.

- "South Asia's Power Sector Relatively Unaffected by Global Financial Crisis, Says New Report". Energy Sector Management Assistance Program. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh no longer dependent on foreign aid". Khabar Southasia. 23 February 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh economy growth 'best in decades'". The Express Tribune. Karachi. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh grows – on remittances, exports". Bdnews24.com. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Bangladesh eligible for UN 'developing country' status". bdnews24.com. Dhaka. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Bangladesh secures UN 'developing country' status". The Independent. Dhaka. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

External links

- Bangladesh Economic Development at Curlie

- Bangladesh Economic News

- Bangladesh Budget 2007 – 2008

- Budget in Brief 2016–17

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Bangladesh, 2007

![]()

![]()