Rail transport in Italy

The Italian railway system is one of the most important parts of the infrastructure of Italy, with a total length[3] of 24,227 km (15,054 mi) of which active lines are 16,723 km.[2] The network has recently grown with the construction of the new high-speed rail network. Italy is a member of the International Union of Railways (UIC). The UIC Country Code for Italy is 83.

| Italy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Operation | |

| National railway | Ferrovie dello Stato |

| Major operators | Trenitalia (national) Nuovo Trasporto Viaggiatori (national) Trenord (local) Trasporto Passeggeri Emilia Romagna (local) Thello (international) Mercitalia (freight) |

| Statistics | |

| Ridership | 848,757,000 (2017)[1] |

| System length | |

| Total | 16,723 km (10,391 mi)[2] |

| Double track | 7,505 km (4,663 mi)[2] |

| Track gauge | |

| Main | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | |

| 3 kV DC | 11,921 km (7,407 mi) (conventional lines) |

| 25 kV AC | 1,296 km (805 mi) (high-speed lines) |

The network

RFI (Rete Ferroviaria Italiana, Italian Rail Network), a state owned infrastructure manager which administers most of the Italian rail infrastructure. The total length of RFI active lines is 16,723 km (10,391 mi),[2] of which 7,505 km (4,663 mi) are double tracks.[2] Lines are divided into 3 categories:

- fundamental lines (fondamentali), which have high traffic and good infrastructure quality, comprise all the main lines between major cities throughout the country. Fundamental lines are 6,131 km (3,810 mi) long;

- complementary lines (complementari), which have less traffic and are responsible for connecting medium or small regional centers. Most of these lines are single track and some are not electrified;

- node lines (di nodo), which link complementary and fundamental lines near metropolitan areas for a total 936 km (582 mi).[2]

Most of the Italian network is electrified (11,921 km (7,407 mi)). Electric system is 3 kV DC on conventional lines and 25 kV AC on high-speed lines.[4]

The Italian rail network comprises also other minor regional lines controlled by other companies, such as Ferrovie Emilia Romagna and Ferrovie del Sud Est, for a total of about 3,000 km.

History

The first railway in Italy was the Napoli-Portici line, built in 1839 to connect the royal palace of Naples to the seaside. After the creation of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, a project was started to build a network from the Alps to Sicily, in order to connect the country.

The first high-speed train was the Italian ETR 200, which in July 1939 went from Milan to Florence at 165 km/h (103 mph), with a top speed of 203 km/h (126 mph).[5] With this service, the railway was able to compete with the upcoming airplanes. The Second World War stopped these services.

After the Second World War, Italy started to repair the damaged railways, and built nearly 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of new tracks.

Nowadays the rail tracks and infrastructure are managed by Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI),[6] while the train and the passenger section is managed mostly by Trenitalia. Both are Ferrovie dello Stato (FS) subsidiaries, once the only train operator in Italy.

High-speed rail

High-speed trains were developed during the 1960s. E444 locomotives were the first standard locomotives capable of top speed of 200 km/h (120 mph), while an ALe 601 electrical multiple unit (EMU) reached a speed of 240 km/h (150 mph) during a test. Other EMUs, such as the ETR 220, ETR 250 and ETR 300, were also updated for speeds up to 200 km/h (120 mph). The braking systems of cars were updated to match the increased travelling speeds.

On 25 June 1970, work was started on the Rome–Florence Direttissima, the first high-speed line in Italy. It included the 5.375-kilometre-long (3.340 mi) bridge on the Paglia river, then the longest in Europe. Works were completed in the early 1990s.

In 1975, a program for a widespread updating of the rolling stock was launched. However, as it was decided to put more emphasis on local traffic, this caused a shifting of resources from the ongoing high-speed projects, with their subsequent slowing or, in some cases, total abandonment. Therefore, 160 E.656 electric and 35 D.345 locomotives for short-medium range traffic were acquired, together with 80 EMUs of the ALe 801/940 class, 120 ALn 668 diesel railcars. Some 1,000 much-needed passenger and 7,000 freight cars were also ordered.

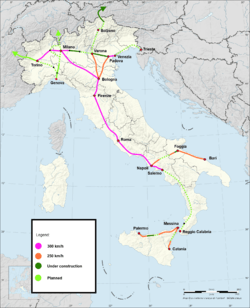

In the 1990s, work started on the Treno Alta Velocità (TAV) project, which involved building a new high-speed network on the routes Milan – (Bologna–Florence–Rome–Naples) – Salerno, Turin – (Milan–Verona–Venice) – Trieste and Milan–Genoa. Most of the planned lines have already been opened, while international links with France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia are underway.

Most of the Rome–Naples line opened in December 2005, the Turin–Milan line partially opened in February 2006 and the Milan–Bologna line opened in December 2008. The remaining sections of the Rome–Naples and the Turin–Milan lines and the Bologna–Florence line were completed in December 2009. All these lines are designed for speeds up to 300 km/h (190 mph).

Other proposed high-speed lines are Salerno-Reggio Calabria, then connected to Sicily using the future Strait of Messina Bridge, and Naples-Bari.

Rail links to adjacent countries

All links have the same gauge.

Stations on the border are:

- Ventimiglia is the border station on the Genoa-Nice main line.

- Modane is the border station on the Turin-Lyon main line (Fréjus Tunnel line).

- Domodossola is the border station of the Milan-Bern/Geneva main line (Simplon Tunnel line).

- Luino is the border station of the Oleggio–Pino railway.

- Chiasso is the border station of the Milan-Zürich main line (Gotthard Tunnel line).

- Tirano is the terminus on the Italian side of the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) Bernina line of the Rhätische Bahn.

- Brenner is the border station of the Verona-Innsbruck main line (Brenner railway).

- San Candido is the border station of the Fortezza-Lienz secondary line.

- Tarvisio Boscoverde is the border station of the Venezia-Wien main line (Austrian Southern Railway line).

- Gorizia Centrale station serves as link to the Slovenian Railways, through the station of Nova Gorica, which can be entered also directly by pedestrians from the Italian side.

- Villa Opicina station (Villa Opicina, Trieste) serves as link to the Slovenian Railways, through the stations of Sežana and Repentabor.

Subsidies

The Italian railways are partially funded by the government, receiving €8.1 billion of rail subsidies in 2009.[7]

Categories and types of trains

These are the major service categories and models of Italian trains.

Italo operates on main High-Speed lines by NTV. Makes a few stops in the most important cities.

Italo operates on main High-Speed lines by NTV. Makes a few stops in the most important cities. Frecciarossa operates on High-Speed lines by Trenitalia. Makes a few stops in major cities.

Frecciarossa operates on High-Speed lines by Trenitalia. Makes a few stops in major cities..jpg) Frecciargento operates on High-Speed lines by Trenitalia. Makes some stops in big cities.

Frecciargento operates on High-Speed lines by Trenitalia. Makes some stops in big cities. Frecciabianca operates on main lines by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities.

Frecciabianca operates on main lines by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities. Intercity operates on main lines by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities.

Intercity operates on main lines by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities. Eurocity, formerly Cisalpino, operates on international main lines within the European Union by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities.

Eurocity, formerly Cisalpino, operates on international main lines within the European Union by Trenitalia. Stops in big cities. RegionaleVeloce operates on regional lines in a region or in adjacent regions by Trenitalia. Stops in the main stations of the local service.

RegionaleVeloce operates on regional lines in a region or in adjacent regions by Trenitalia. Stops in the main stations of the local service. Regionale operates on regional lines by Trenitalia. Stops in every station of the local service.

Regionale operates on regional lines by Trenitalia. Stops in every station of the local service. Regio-Express operates on regional lines by Trenord. Stops in some station of the local service.

Regio-Express operates on regional lines by Trenord. Stops in some station of the local service. Regionale as operates in Trentino-Alto Adige by SAD

Regionale as operates in Trentino-Alto Adige by SAD Regionale as operates in some lines of Veneto by Sistemi Territoriali (ST)

Regionale as operates in some lines of Veneto by Sistemi Territoriali (ST)- Regionale as operates in Friuli-Venezia Giulia by Società Ferrovie Udine-Cividale (FUC)

Regionale as operates in Apulia by Ferrovie del Sud Est (FSE)

Regionale as operates in Apulia by Ferrovie del Sud Est (FSE)

Main stations

Milano Centrale, Milan

Milano Centrale, Milan

See also

References

- "Railway passenger transport statistics - Europa EU" (PDF). ec.europa.eu. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "La rete oggi". RFI Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Total length of tracks: double tracks are counted twice.

- "Il sistema di elettrificazione a 25kV c.a." RFI Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Cornolo Giovanni. Una leggenda che corre: breve storia dell'elettrotreno e dei suoi primati; ETR.200 – ETR.220 – ETR 240. ISBN 88-85068-23-5

- "Ferrovie dello Stato" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- "The age of the train" (PDF).

Bibliography

- Parks, Tim (2013). Italian Ways: On and Off the Rails from Milan to Palermo. London: Harvill Secker. ISBN 9781846557743.

- Fascicolo Linea 82 bis – AV/AC Torino – Milano – Napoli Tratto di linea Milano Rogoredo – Firenze Castello e relative interconnessioni con linea Milano – Bologna – Firenze (Tradizionale) (in Italian). Rete Ferroviaria Italiana. pp. 90–119 and 150–179.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rail transport in Italy. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rail travel in Italy. |

- RFI (Infrastructure manager) Official website (Italian only)

- Lyon Turin Ferroviaire

- Railway Technology.com article on Italian High Speed Rail, including NTV, Accessed 5 February 2008

- Italian HS System