Lombard League

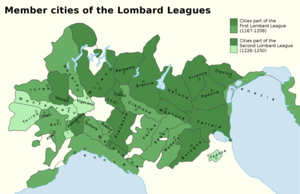

The Lombard League (Lega Lombarda in Italian, Liga Lombarda in Lombard) was a medieval alliance formed in 1167,[1] supported by the Pope, to counter the attempts by the Hohenstaufen Holy Roman Emperors to assert influence over the Kingdom of Italy as a part of the Holy Roman Empire. At its apex, it included most of the cities of Northern Italy, but its membership changed with time. With the death of the third and last Hohenstaufen emperor, Frederick II, in 1250, it became obsolete and was disbanded.

History

The association succeeded the Veronese League, established in 1164 by Verona, Padua, Vicenza, and the Republic of Venice, after Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa had claimed direct Imperial control over Italy at the 1158 Diet of Roncaglia and began to replace the Podestà magistrates by his own commissioners. It was backed by Pope Alexander III (the town of Alessandria was named in his honour), who also wished to see Frederick's power in Italy decline.[2] Formed at Pontida on 1 December 1167, the Lombard League included—beside Verona, Padua, Vicenza and Venice—cities like Crema, Cremona, Mantua, Piacenza, Bergamo, Brescia, Milan, Genoa, Bologna, Modena, Reggio Emilia, Treviso, Vercelli, Lodi, Parma, Ferrara and even some lords, such as the Marquis Malaspina and Ezzelino da Romano.

Though not a declared separatist movement, the League openly challenged the emperor's claim to power (Honor Imperii). Frederick I strived against the cities, especially Milan, which already had been occupied and devastated in 1162. He nevertheless was no longer able to play off the cities against each other. At the Battle of Legnano on 29 May 1176, the emperor's army finally was defeated. The Treaty of Venice, which took place in 1177, established a six-year truce from August, 1178 to 1183, when in the Peace of Constance a compromise was found where after the Italian cities agreed to remain loyal to the Holy Roman Empire but retained local jurisdiction and droit de régale over their territories. Among the League's members, Milan, now favoured by the emperor, began to take a special position, which sparked conflicts mainly with the citizens of Cremona.

- Lombard milites depicted on the Porta Romana relief of 1171

A Bronze replica of the Peace of Constance in Konstanz. Illustrating the comunes of the Lombard League in 1183.

A Bronze replica of the Peace of Constance in Konstanz. Illustrating the comunes of the Lombard League in 1183.

The Lombard League was renewed several times and upon the death of Frederick's son Emperor Henry VI in 1197 once again gained prestige, while Henry's minor son Frederick II, elected King of the Romans, had to fight for the Imperial throne against his Welf rival Otto IV. In 1226 Frederick, sole king since 1218 and emperor since 1220, aimed to convene the Princes in Italy in order to prepare the Sixth Crusade.

The efforts of Emperor Frederick II to gain greater power in Italy were aborted by the cities, which earned the League an Imperial ban. The emperor's measures included the taking of Vicenza and his victory in the 1237 Battle of Cortenuova which established the reputation of the Emperor as a skillful strategist.[2] Nevertheless, he misjudged his strength, rejecting all Milanese peace overtures and insisting on unconditional surrender. It was a moment of grave historic importance, when Frederick's hatred coloured his judgment and blocked all possibilities of a peaceful settlement. Milan and five other cities withstood his attacks, and in October 1238 he had to unsuccessfully raise the siege of Brescia.

- Medieval miniature depicting the Battle of Cortenuova (1237)

Medieval miniature depicting the Battle of Parma (1248)

Medieval miniature depicting the Battle of Parma (1248)- Medieval miniature depicting the Battle of Fossalta (1249)

The Lombard League once again receiving papal support by Pope Gregory IX, who excommunicated Frederick II in 1239,[3] and effectively countered the emperor's efforts. During the 1248 Siege of Parma, the Imperial camp was assaulted and taken, and in the ensuing battle the Imperial side was routed. Frederick II lost the Imperial treasure and with it any hope of maintaining the impetus of his struggle against the rebellious communes and against the pope. The League was dissolved in 1250 when Frederick II died. Under his later successors the Empire exerted much less influence on Italian politics.

The civil government

In addition of being a military alliance, the Lombard League was one of the first examples of confederal system in the world of communes. Indeed, the League had a distinct council of its members, called Universitas, consisting of representatives appointed by individual municipalities, and which voted by majority in various fields (such as the admission of new members, war and peace with the Emperor), powers that grew more and more with the years, so that the university obtained regulatory, tax and judicial power, a system comparable to that of a present-day republic.[4]

In the first period of the League the communes had little to do with confederal affairs, and the members of the Universitas were independent; in the second period the municipalities gained some influence but, as a counterweight, members was more involved in the municipal council policy. In addition, the League abolished the duties with the creation of a customs union.[4]

See also

- Pontida's Oath

- Stadtrecht (Town Rights)

- Städtebund (Town League)

- Guelphs and Ghibellines

- Old Swiss Confederacy

- Lusatian League

- Décapole

- Hanseatic League

- Ariberto da Intimiano

References

- Lombard League, Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 12 February 2013

- The Papacy, J.A. Watt, The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, c.1198-c.1300, ed. David Abulafia, Rosamond McKitterick, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 135.

- Björn K. U. Weiler, Henry III of England and the Staufen Empire, 1216-1272, (Boydell & Brewer, 2006), 86.

- (in Italian) Lega Lombarda, Federiciana

Sources

- Gianluca Raccagni, The Lombard League (1164–1225), Oxford University Press 2010.

- "Lombard League." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 6 Apr 2008 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9048806>.

- G. Fasoli,"La Lega Lombarda --Antecedenti,formazione, struttura," Problema des 12.Jahrhunderts,

- Vortraege und Forchungegen, 12, 1965–67, pp. 143–160.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.