Life Is Beautiful

Life Is Beautiful (Italian: La vita è bella, Italian pronunciation: [la ˈviːta ˈɛ bˈbɛlla]) is a 1997 Italian comedy-drama film directed by and starring Roberto Benigni, who co-wrote the film with Vincenzo Cerami. Benigni plays Guido Orefice, a Jewish Italian bookshop owner, who employs his fertile imagination to shield his son from the horrors of internment in a Nazi concentration camp. The film was partially inspired by the book In the End, I Beat Hitler by Rubino Romeo Salmonì and by Benigni's father, who spent two years in a German labour camp during World War II.

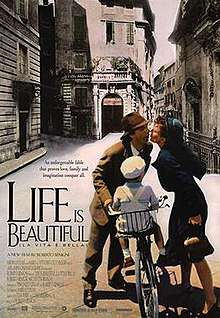

| Life Is Beautiful | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roberto Benigni |

| Produced by | Gianluigi Braschi Elda Ferri |

| Written by | Roberto Benigni Vincenzo Cerami |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Nicola Piovani |

| Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Edited by | Simona Paggi |

Production company | Melampo Cinematografica |

| Distributed by | Cecchi Gori Group (Italy) Miramax Films (USA/International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[1] |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian German English |

| Budget | $20 million[2] |

| Box office | $230.1 million[3] |

The film was a critical and financial success. It grossed over $230 million worldwide, becoming one of the highest-grossing non-English language movies of all time,[4] and received widespread acclaim, despite some criticisms of using the subject matter for comedic purposes. It won the Grand Prix at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, nine David di Donatello Awards (including Best Film), five Nastro d'Argento Awards in Italy, two European Film Awards, and three Academy Awards (including Best Foreign Language Film and Best Actor for Benigni).

Plot

In 1939, in the Kingdom of Italy, Guido Orefice is a young Jewish man who arrives to work in the city (Arezzo, in Tuscany) where his uncle Eliseo operates a restaurant. Guido is comical and sharp, and falls in love with a Gentile girl named Dora. Later, he sees her again in the city where she is a teacher and set to be engaged to a rich, but arrogant, man, a local government official with whom Guido has regular run-ins. Guido sets up many "coincidental" incidents to show his interest in Dora. Finally, Dora sees Guido's affection and promise, and gives in, against her better judgement. He steals her from her engagement party, on a horse, humiliating her fiancé and mother. They are later married and have a son, Giosuè, and run a bookstore.

When World War II breaks out, Guido, his uncle Eliseo, and Giosuè are seized on Giosuè's birthday. They and many other Jews are forced onto a train and taken to a concentration camp. After confronting a guard about her husband and son, and being told there is no mistake, Dora volunteers to get on the train in order to be close to her family. However, as men and women are separated in the camp, Dora and Guido never see each other during the internment. Guido pulls off various stunts, such as using the camp's loudspeaker to send messages—symbolic or literal—to Dora to assure her that he and their son are safe. Eliseo is executed in a gas chamber shortly after their arrival. Giosuè narrowly avoids being gassed himself as he hates to take baths and showers, and did not follow the other children when they had been ordered to enter the gas chambers and were told they were showers.

In the camp, Guido hides their true situation from his son. Guido explains to Giosuè that the camp is a complicated game in which he must perform the tasks Guido gives him. Each of the tasks will earn them points and whoever gets to one thousand points first will win a tank. He tells him that if he cries, complains that he wants his mother, or says that he is hungry, he will lose points, while quiet boys who hide from the camp guards earn extra points. Giosuè is at times reluctant to go along with the game, but Guido convinces him each time to continue. At one point Guido takes advantage of the appearance of visiting German officers and their families to show Giosuè that other children are hiding as part of the game, and he also takes advantage of a German nanny thinking Giosuè is one of her charges in order to feed him as Guido serves the German officers. Guido and Giosuè are almost found out to be prisoners by another server until Guido is found teaching all of the German children how to say "Thank you" in Italian.

Guido maintains this story right until the end when, in the chaos of shutting down the camp as the Allied forces approach, he tells his son to stay in a box until everybody has left, this being the final task in the competition before the promised tank is his. Guido goes to find Dora, but he is caught by a German soldier. An officer makes the decision to execute Guido, who is led off by the soldier. While he is walking to his death, Guido passes by Giosuè one last time and winks, still in character and playing the game. Guido is then shot and left for dead in an alleyway. The next morning, Giosuè emerges from the sweat-box, just as a US Army unit led by a Sherman tank arrives and the camp is liberated. Giosuè is overjoyed about winning the game (unaware that his father is dead), thinking that he won the tank, and an American soldier allows Giosuè to ride on the tank. While travelling to safety, Giosuè soon spots Dora in the procession leaving the camp and reunites with his mother. While the young Giosuè excitedly tells his mother about how he had won a tank, just as his father had promised, the adult Giosuè, in an overheard monologue, reminisces on the sacrifices his father made for him and his story.

Cast

- Roberto Benigni as Guido Orefice

- Nicoletta Braschi as Dora Orefice

- Giorgio Cantarini as Giosuè Orefice

- Giustino Durano as Uncle Eliseo

- Horst Buchholz as Doctor Lessing

- Marisa Paredes as Dora's mother

- Sergio Bustric as Ferruccio

- Amerigo Fontani as Rodolfo

- Lydia Alfonsi as Guicciardini

- Giuliana Lojodice as the Headmistress

- Pietro Desilva as Bartolomeo

- Francesco Guzzo as Vittorino

- Raffaella Lebboroni as Elena

- Claudio Alfonsi as Amico Rodolfo

- Gil Baroni as the Prefect

- Ennio Consalvi as General Graziosi

- Aaron Craig as the tank driver

- Alfiero Falomi as King of Italy

Production

Director Roberto Benigni, who wrote the screenplay with Vincenzo Cerami, was inspired by the story of Rubino Romeo Salmonì and his book In the End, I Beat Hitler, which incorporates elements of irony and black comedy.[5] Salmoni was an Italian Jew who was deported to Auschwitz, survived and was reunited with his parents, but found his brothers were murdered. Benigni stated he wished to commemorate Salmoni as a man who wished to live in the right way.[6] He also based the story on that of his father Luigi Benigni, who was a member of the Italian Army after Italy became a co-belligerent of the Allies in 1943.[7] Luigi Benigni spent two years in a Nazi labour camp, and to avoid scaring his children, told about his experiences humorously, finding this helped him cope.[8] Roberto Benigni explained his philosophy, "to laugh and to cry comes from the same point of the soul, no? I'm a storyteller: the crux of the matter is to reach beauty, poetry, it doesn't matter if that is comedy or tragedy. They're the same if you reach the beauty."[9]

His friends advised against making the film, as he is a comedian and not Jewish, and the Holocaust was not of interest to his established audience.[10] Because he is Gentile, Benigni consulted with the Center for Documentation of Contemporary Judaism, based in Milan, throughout production.[11] Benigni incorporated historical inaccuracies in order to distinguish his story from the true Holocaust, about which he said only documentaries interviewing survivors could provide "the truth".[9]

The film was shot in the centro storico (historic centre) of Arezzo, Tuscany. The scene where Benigni falls off a bicycle and lands on Nicoletta Braschi was shot in front of Badia delle Sante Flora e Lucilla in Arezzo.[12]

Release

In Italy, the film was released in 1997 by Cecchi Gori Distribuzione.[13] The film was screened in the Cannes Film Festival in May 1998, where it was a late addition to the selection of films.[14] In the US, it was released on 23 October 1998,[10] by Miramax Films.[15] In the UK, it was released on 12 February 1999.[9] After the Italian, English subtitled version became a hit in English speaking territories, Miramax reissued Life is Beautiful in an English dubbed version, but it was less successful than the subtitled Italian version.[16]

The film was aired on the Italian television station RAI on 22 October 2001 and was viewed by 16 million people. This made it the most watched Italian film on Italian TV.[17]

Reception

Box office

Life is Beautiful was commercially successful, making $48.7 million in Italy.[18] It was the highest-grossing Italian film in its native country until 2011, when surpassed by Checco Zalone's What a Beautiful Day.[19]

The film was also successful in the rest of the world, grossing $57.6 million in the United States and Canada and $123.8 million in other territories, for a worldwide gross of $230.1 million.[3] It was the highest-grossing foreign language film in the United States until Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000).[20]

Critical response

The film was praised by the Italian press, with Benigni treated as a "national hero."[11] Pope John Paul II, who received a private screening with Benigni, placed it in his top five favourite films.[11] Roger Ebert gave the film three and a half stars, stating, "At Cannes, it offended some left-wing critics with its use of humor in connection with the Holocaust. What may be most offensive to both wings is its sidestepping of politics in favor of simple human ingenuity. The film finds the right notes to negotiate its delicate subject matter."[21] Michael O'Sullivan, writing for The Washington Post, called it "sad, funny and haunting."[22] Janet Maslin wrote in The New York Times that the film took "a colossal amount of gall" but "because Mr. Benigni can be heart-rending without a trace of the maudlin, it works."[15] The Los Angeles Times's Kenneth Turan noted the film had "some furious opposition" at Cannes, but said "what is surprising about this unlikely film is that it succeeds as well as it does. Its sentiment is inescapable, but genuine poignancy and pathos are also present, and an overarching sincerity is visible too."[23] David Rooney of Variety said the film had "mixed results," with "surprising depth and poignancy" in Benigni's performance but "visually rather flat" camera work by Tonino Delli Colli.[13] Owen Glieberman of Entertainment Weekly gave it a B−, calling it "undeniably some sort of feat—the first feel-good Holocaust weepie. It's been a long time coming." However, Glieberman stated the flaw is "As shot, it looks like a game."[24]

In 2002, BBC critic Tom Dawson wrote "the film is presumably intended as a tribute to the powers of imagination, innocence, and love in the most harrowing of circumstances," but "Benigni's sentimental fantasy diminishes the suffering of Holocaust victims."[25] In 2006, Jewish American comedic filmmaker Mel Brooks spoke negatively of the film in Der Spiegel, saying it trivialized the suffering in concentration camps.[26] By contrast, Nobel Laureate Imre Kertész argues that those who take the film to be a comedy, rather than a tragedy, have missed the point of the film. He draws attention to what he terms 'Holocaust conformism' in cinema to rebuff detractors of Life Is Beautiful.[27]

The film holds a "Fresh" 80% approval rating on review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 87 reviews with an average rating of 7.58/10. The site's consensus reads:"Benigni's earnest charm, when not overstepping its bounds into the unnecessarily treacly, offers the possibility of hope in the face of unflinching horror".[28]

Accolades

Life is Beautiful was shown at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, and went on to win the Grand Prix.[29] Upon receiving the award, Benigni kissed the feet of jury president Martin Scorsese.[23]

At the 71st Academy Awards, Benigni won Best Actor for his role, with the film winning two more awards for Best Music, Original Dramatic Score and Best Foreign Language Film.[30] Benigni jumped on top of the seats as he made his way to the stage to accept his first award, and upon accepting his second, said, "This is a terrible mistake because I used up all my English!"[31]

Soundtrack

The original score to the film was composed by Nicola Piovani,[13] with the exception of a classical piece which figures prominently: the "Barcarolle" by Jacques Offenbach. The soundtrack album won the Academy Award for Best Original Dramatic Score[30] and was nominated for a Grammy Award: "Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media", but lost to the score of A Bug's Life.

See also

- List of submissions to the 71st Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Italian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- "La Vita E Bella (Life Is Beautiful) (12A)". Buena Vista International. British Board of Film Classification. 26 November 1998. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Box Office Information for Life is Beautiful". The Wrap. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "Life is Beautiful". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- John, Adriana. "Top 10 Highest Grossing Non-English Movies of All Time". Wonderslist. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- Squires, Nick (11 July 2011). "Life Is Beautiful Nazi death camp survivor dies aged 91". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Paradiso, Stefania (10 July 2011). "E' morto Romeo Salmonì: l'uomo che ispirò Benigni per La vita è bella". Un Mondo di Italiani. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Norden 2007, p. 146.

- Piper 2003, p. 12.

- Logan, Brian (29 January 1999). "Does this man really think the Holocaust was a big joke?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Okwu, Michael (23 October 1998). "'Life Is Beautiful' through Roberto Benigni's eyes". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Stone, Alan A. (1 April 1999). "Escape from Auschwitz". Boston Review. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Warkentin, Elizabeth (30 May 2016). "Life truly is beautiful in Tuscany's underappreciated Arezzo". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Rooney, David (3 January 1998). "Review: 'Life Is Beautiful'". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Piper 2003, p. 11.

- Maslin, Janet (23 October 1998). "Giving a Human (and Humorous) Face to Rearing a Boy Under Fascism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "Benigni's 'Pinocchio' Out With Subtitles". Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Benigni, audience da record oltre 16 milioni di spettatori". La Repubblica. 23 October 2001. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Perren 2012, p. 274.

- "Checco Zalone supera Benigni". tgcom24.mediaset.it. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "Foreign Language". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (30 October 1998). "Life Is Beautiful". Rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- O'Sullivan, Michael (30 October 1998). "'Life's' Surprisingly Graceful Turn'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Turan, Kenneth (23 October 1998). "The Improbable Success of 'Life Is Beautiful'". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Glieberman, Owen (6 November 1998). "Life Is Beautiful". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Dawson, Tom (6 June 2002). "La Vita è Bella (Life is Beautiful) (1998)". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Brooks, Mel (16 March 2006). "SPIEGEL Interview with Mel Brooks: With Comedy, We Can Rob Hitler of his Posthumous Power". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- MacKay, John; Kertész, Imre (1 April 2001). "Who Owns Auschwitz?". The Yale Journal of Criticism. 14 (1): 267–272. doi:10.1353/yale.2001.0010. ISSN 1080-6636.

- "Life is Beautiful". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- "Festival de Cannes: Life is Beautiful". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- Higgins, Bill (24 February 2012). "How 'Life Is Beautiful's' Roberto Benigni Stole the Oscars Show in 1999". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "1999 Winners & Nominees". AACTA.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Lister, David (11 April 1999). "Good night at Baftas for anyone called Elizabeth". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "César du Meilleur film étranger - César". AlloCiné. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Clinton, Paul (26 January 1999). "Broadcast Film critics name 'Saving Private Ryan' best film". CNN. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "La vita è bella - Premi vinti: 9". David di Donatello. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- "European Film Awards Winners 1998". European Film Academy. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- Madigan, Nick (7 March 1999). "SAG tells Benigni 'Life' is beautiful". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

Bibliography

- Bullaro, Grace Russo (2005). Beyond "Life is Beautiful": comedy and tragedy in the cinema of Roberto Benigni. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-904744-83-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norden, Martin F., ed. (2007). The Changing Face of Evil in Film and Television. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. ISBN 9042023244.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perren, Alisa (2012). Indie, Inc.: Miramax and the Transformation of Hollywood in the 1990s. University of Texas Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piper, Kerrie (2003). Life is Beautiful. Pascal Press. ISBN 1741250307.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Life Is Beautiful |