Latin alphabet

The Latin or Roman alphabet is the set of letters originally used by the ancient Romans to write Latin.

| Latin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages |

|

Time period | c. 700 BC – present |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | Numerous Latin alphabets; also more divergent derivations such as Osage |

Sister systems | Cyrillic script Armenian alphabet Georgian script Coptic alphabet Runes |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Latn, 215 |

Unicode alias | Latin |

Unicode range | See Latin characters in Unicode |

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

Hangul 1443 Thaana 18 c. CE (derived from Brahmi numerals) |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Etymology

The term Latin alphabet may refer to either the alphabet used to write Latin (as described in this article) or other alphabets based on the Latin script, which is the basic set of letters common to the various alphabets descended from the classical Latin alphabet, such as the English alphabet. These Latin-script alphabets may discard letters, like the Rotokas alphabet or add new letters, like the Danish and Norwegian alphabets. Letter shapes have evolved over the centuries, including the development in Medieval Latin of lower-case, forms which did not exist in the Classical period alphabet.

Evolution

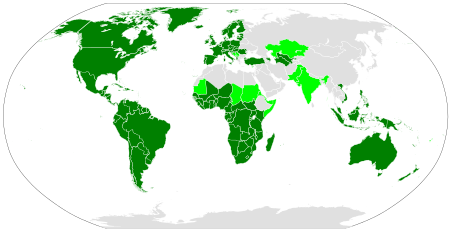

Due to its use in writing Germanic, Romance and other languages first in Europe and then in other parts of the world and due to its use in Romanizing writing of other languages, it has become widespread (see Latin script). It is also used officially in Asian countries such as China (separate from its ideographic writing), Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, and has been adopted by Baltic and some Slavic states.

The Latin alphabet evolved from the visually similar Etruscan alphabet, which evolved from the Cumaean Greek version of the Greek alphabet, which was itself descended from the Phoenician alphabet, which in turn derived from Egyptian hieroglyphics.[1] The Etruscans ruled early Rome; their alphabet evolved in Rome over successive centuries to produce the Latin alphabet.

During the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was used (sometimes with modifications) for writing Romance languages, which are direct descendants of Latin, as well as Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and some Slavic languages. With the age of colonialism and Christian evangelism, the Latin script spread beyond Europe, coming into use for writing indigenous American, Australian, Austronesian, Austroasiatic and African languages. More recently, linguists have also tended to prefer the Latin script or the International Phonetic Alphabet (itself largely based on the Latin script) when transcribing or creating written standards for non-European languages, such as the African reference alphabet.

Diacritics

Although it does not seem that classical Latin used diacritics (accents etc), modern English is the only major modern European language that does not have any for native words.[note 1]

Signs and abbreviations

Although Latin did not use diacritical signs, signs of truncation of words, often placed above the truncated word or at the end of it, were very common. Furthermore, abbreviations or smaller overlapping letters were often used. This was due to the fact that if the text was engraved on the stone, the number of letters to be written was reduced, while if it was written on paper or parchment, it was spared the space, which was very precious. This habit continued even in the Middle Ages. Hundreds of symbols and abbreviations exist, varying from century to century.[4]

History

Old Italic alphabet

| Letters | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌈 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌎 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌑 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 | 𐌘 | 𐌙 | 𐌚 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | A | B | C | D | E | V | Z | H | Θ | I | K | L | M | N | Ξ | O | P | Ś | Q | R | S | T | Y | X | Φ | Ψ | F |

Archaic Latin alphabet

| As Old Italic | 𐌀 | 𐌁 | 𐌂 | 𐌃 | 𐌄 | 𐌅 | 𐌆 | 𐌇 | 𐌉 | 𐌊 | 𐌋 | 𐌌 | 𐌍 | 𐌏 | 𐌐 | 𐌒 | 𐌓 | 𐌔 | 𐌕 | 𐌖 | 𐌗 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Latin | A | B | C | D | E | F | Z | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X |

The letter ⟨C⟩ was the western form of the Greek gamma, but it was used for the sounds /ɡ/ and /k/ alike, possibly under the influence of Etruscan, which might have lacked any voiced plosives. Later, probably during the 3rd century BC, the letter ⟨Z⟩ – unneeded to write Latin properly – was replaced with the new letter ⟨G⟩, a ⟨C⟩ modified with a small horizontal stroke, which took its place in the alphabet. From then on, ⟨G⟩ represented the voiced plosive /ɡ/, while ⟨C⟩ was generally reserved for the voiceless plosive /k/. The letter ⟨K⟩ was used only rarely, in a small number of words such as Kalendae, often interchangeably with ⟨C⟩.

Classical Latin alphabet

After the Roman conquest of Greece in the 1st century BC, Latin adopted the Greek letters ⟨Y⟩ and ⟨Z⟩ (or readopted, in the latter case) to write Greek loanwords, placing them at the end of the alphabet. An attempt by the emperor Claudius to introduce three additional letters did not last. Thus it was during the classical Latin period that the Latin alphabet contained 23 letters:

| Letter | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | V | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin name (majus) | á | bé | cé | dé | é | ef | gé | há | ꟾ | ká | el | em | en | ó | pé | qv́ | er | es | té | v́ | ix | ꟾ graeca | zéta |

| Latin name | ā | bē | cē | dē | ē | ef | gē | hā | ī | kā | el | em | en | ō | pē | qū | er | es | tē | ū | ix | ī Graeca | zēta |

| Latin pronunciation (IPA) | aː | beː | keː | deː | eː | ɛf | ɡeː | haː | iː | kaː | ɛl | ɛm | ɛn | oː | peː | kuː | ɛr | ɛs | teː | uː | iks | iː ˈɡraeka | ˈdzeːta |

The Latin names of some of these letters are disputed; for example, ⟨H⟩ may have been called Latin pronunciation: [ˈaha] or Latin pronunciation: [ˈaka].[5] In general the Romans did not use the traditional (Semitic-derived) names as in Greek: the names of the plosives were formed by adding /eː/ to their sound (except for ⟨K⟩ and ⟨Q⟩, which needed different vowels to be distinguished from ⟨C⟩) and the names of the continuants consisted either of the bare sound, or the sound preceded by /e/.

The letter ⟨Y⟩ when introduced was probably called "hy" /hyː/ as in Greek, the name upsilon not being in use yet, but this was changed to "i Graeca" (Greek i) as Latin speakers had difficulty distinguishing its foreign sound /y/ from /i/. ⟨Z⟩ was given its Greek name, zeta. This scheme has continued to be used by most modern European languages that have adopted the Latin alphabet. For the Latin sounds represented by the various letters see Latin spelling and pronunciation; for the names of the letters in English see English alphabet.

Diacritics were not regularly used, but they did occur sometimes, the most common being the apex used to mark long vowels, which had previously sometimes been written doubled. However, in place of taking an apex, the letter i was written taller: ⟨á é ꟾ ó v́⟩. For example, what is today transcribed Lūciī a fīliī was written ⟨lv́ciꟾ·a·fꟾliꟾ⟩ in the inscription depicted.

The primary mark of punctuation was the interpunct, which was used as a word divider, though it fell out of use after 200 AD.

Old Roman cursive script, also called majuscule cursive and capitalis cursive, was the everyday form of handwriting used for writing letters, by merchants writing business accounts, by schoolchildren learning the Latin alphabet, and even emperors issuing commands. A more formal style of writing was based on Roman square capitals, but cursive was used for quicker, informal writing. It was most commonly used from about the 1st century BC to the 3rd century, but it probably existed earlier than that. It led to Uncial, a majuscule script commonly used from the 3rd to 8th centuries AD by Latin and Greek scribes.

New Roman cursive script, also known as minuscule cursive, was in use from the 3rd century to the 7th century, and uses letter forms that are more recognizable to modern eyes; ⟨a⟩, ⟨b⟩, ⟨d⟩, and ⟨e⟩ had taken a more familiar shape, and the other letters were proportionate to each other. This script evolved into the medieval scripts known as Merovingian and Carolingian minuscule.

Medieval and later developments

| Uppercase Latin alphabet | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase Latin alphabet | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

The use of the letters I and V for both consonants and vowels proved inconvenient as the Latin alphabet was adapted to Germanic and Romance languages. W originated as a doubled V (VV) used to represent the Voiced labial–velar approximant /w/ found in Old English as early as the 7th century. It came into common use in the later 11th century, replacing the letter wynn ⟨Ƿ ƿ⟩, which had been used for the same sound. In the Romance languages, the minuscule form of V was a rounded u; from this was derived a rounded capital U for the vowel in the 16th century, while a new, pointed minuscule v was derived from V for the consonant. In the case of I, a word-final swash form, j, came to be used for the consonant, with the un-swashed form restricted to vowel use. Such conventions were erratic for centuries. J was introduced into English for the consonant in the 17th century (it had been rare as a vowel), but it was not universally considered a distinct letter in the alphabetic order until the 19th century.

With the fragmentation of political power, the style of writing changed and varied greatly throughout the Middle Ages, even after the invention of the printing press. Early deviations from the classical forms were the uncial script, a development of the Old Roman cursive, and various so-called minuscule scripts that developed from New Roman cursive, of which the Carolingian minuscule was the most influential, introducing the lower case forms of the letters, as well as other writing conventions that have since become standard.

The languages that use the Latin script generally use capital letters to begin paragraphs and sentences and proper nouns. The rules for capitalization have changed over time, and different languages have varied in their rules for capitalization. Old English, for example, was rarely written with even proper nouns capitalized, whereas Modern English writers and printers of the 17th and 18th century frequently capitalized most and sometimes all nouns,[6] which is still systematically done in Modern German, e.g. in the preamble and all of the United States Constitution: We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Spread

The Latin alphabet spread, along with Latin, from the Italian Peninsula to the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea with the expansion of the Roman Empire. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet.

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the script was gradually adopted by the peoples of northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets), Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian. The Latin alphabet came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism.

Later, it was adopted by non-Catholic countries. Romanian, most of whose speakers are Orthodox, was the first major language to switch from Cyrillic to Latin script, doing so in the 19th century, although Moldova only did so after the Soviet collapse.

It has also been increasingly adopted by Turkic-speaking countries, beginning with Turkey in the 1920s. After the Soviet collapse, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan all switched from Cyrillic to Latin. The government of Kazakhstan announced in 2015 that the Latin alphabet would replace Cyrillic as the writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.[7]

The spread of the Latin alphabet among previously illiterate peoples has inspired the creation of new writing systems, such as the Avoiuli alphabet in Vanuatu, which replaces the letters of the Latin alphabet with alternative symbols.

See also

- Latin spelling and pronunciation

- Calligraphy

- Euboean alphabet

- Latin script in Unicode

- ISO basic Latin alphabet

- Latin-1

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Palaeography

- Phoenician alphabet

- Pinyin

- Roman letters used in mathematics

- Typography

- Western Latin character sets (computing)

Notes

References

- Michael C. Howard (2012), Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies. p. 23.

- Grafton, Anthony (2006-10-23). "Books: The Nutty Professors, The history of academic charisma". The New Yorker.

- "The New Yorker's odd mark — the diaeresis". 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- Cappelli, Adriano (1990). Dizionario di Abbreviature Latine ed Italiane. Milano: Editore Ulrico Hoepli. ISBN 88-203-1100-3.

- Liberman, Anatoly (7 August 2013). "Alphabet soup, part 2: H and Y". Oxford Etymologist. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Crystal, David (4 August 2003). "The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- Kazakh language to be converted to Latin alphabet – MCS RK. Inform.kz (30 January 2015). Retrieved on 2015-09-28.

Further reading

- Jensen, Hans (1970). Sign Symbol and Script. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. ISBN 0-04-400021-9. Transl. of Jensen, Hans (1958). Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften., as revised by the author

- Rix, Helmut (1993). "La scrittura e la lingua". In Cristofani, Mauro (hrsg.) (ed.). Gli etruschi – Una nuova immagine. Firenze: Giunti. pp. S.199–227.

- Sampson, Geoffrey (1985). Writing systems. London (etc.): Hutchinson.

- Wachter, Rudolf (1987). Altlateinische Inschriften: sprachliche und epigraphische Untersuchungen zu den Dokumenten bis etwa 150 v.Chr. Bern (etc.).: Peter Lang.

- Allen, W. Sidney (1978). "The names of the letters of the Latin alphabet (Appendix C)". Vox Latina – a guide to the pronunciation of classical Latin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22049-1.

- Biktaş, Şamil (2003). Tuğan Tel.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Latin alphabet. |

| Library resources about Latin alphabet |