Pizza

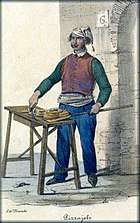

Pizza (Italian: [ˈpittsa], Neapolitan: [ˈpittsə]) is a savory dish of Italian origin consisting of a usually round, flattened base of leavened wheat-based dough topped with tomatoes, cheese, and often various other ingredients (such as anchovies, mushrooms, onions, olives, pineapple, meat, etc.) which is then baked at a high temperature, traditionally in a wood-fired oven.[1] A small pizza is sometimes called a pizzetta. A person who makes pizza is known as a pizzaiolo.

Pizza Margherita, the archetype of Neapolitan pizza | |

| Type | Flatbread |

|---|---|

| Course | Lunch or dinner |

| Place of origin | Italy |

| Region or state | Campania (Naples) |

| Serving temperature | Hot or warm |

| Main ingredients | Dough, sauce (usually tomato sauce), cheese |

| Variations | Calzone, panzerotti, stromboli |

| Part of a series on |

| Pizza |

|---|

.jpg) |

|

Pizza varieties

|

|

Cooking variations

|

|

Pizza tools

|

In Italy, pizza served in formal settings, such as at a restaurant, is presented unsliced, and is eaten with the use of a knife and fork.[2][3] In casual settings, however, it is cut into wedges to be eaten while held in the hand.

The term pizza was first recorded in the 10th century in a Latin manuscript from the Southern Italian town of Gaeta in Lazio, on the border with Campania.[4] Modern pizza was invented in Naples, and the dish and its variants have since become popular in many countries.[5] It has become one of the most popular foods in the world and a common fast food item in Europe and North America, available at pizzerias (restaurants specializing in pizza), restaurants offering Mediterranean cuisine, and via pizza delivery.[5][6] Many companies sell ready-baked frozen pizzas to be reheated in an ordinary home oven.

The Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (lit. True Neapolitan Pizza Association) is a non-profit organization founded in 1984 with headquarters in Naples that aims to promote traditional Neapolitan pizza.[7] In 2009, upon Italy's request, Neapolitan pizza was registered with the European Union as a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed dish,[8][9] and in 2017 the art of its making was included on UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage.[10]

Etymology

The word "pizza" first appeared in a Latin text from the central Italian town of Gaeta, then still part of the Byzantine Empire, in 997 AD; the text states that a tenant of certain property is to give the bishop of Gaeta duodecim pizze ("twelve pizzas") every Christmas Day, and another twelve every Easter Sunday.[4][11]

Suggested etymologies include:

- Byzantine Greek and Late Latin pitta > pizza, cf. Modern Greek pitta bread and the Apulia and Calabrian (then Byzantine Italy) pitta,[12] a round flat bread baked in the oven at high temperature sometimes with toppings. The word pitta can in turn be traced to either Ancient Greek πικτή (pikte), "fermented pastry", which in Latin became "picta", or Ancient Greek πίσσα (pissa, Attic πίττα, pitta), "pitch",[13][14] or πήτεα (pḗtea), "bran" (πητίτης pētítēs, "bran bread").[15]

- The Etymological Dictionary of the Italian Language explains it as coming from dialectal pinza "clamp", as in modern Italian pinze "pliers, pincers, tongs, forceps". Their origin is from Latin pinsere "to pound, stamp".[16]

- The Lombardic word bizzo or pizzo meaning "mouthful" (related to the English words "bit" and "bite"), which was brought to Italy in the middle of the 6th century AD by the invading Lombards.[4][17] The shift b>p could be explained by the High German consonant shift, and it has been noted in this connection that in German the word Imbiss means "snack".

History

Foods similar to pizza have been made since the Neolithic Age.[18] Records of people adding other ingredients to bread to make it more flavorful can be found throughout ancient history. In the 6th century BC, the Persian soldiers of Achaemenid Empire during the rule King Darius I baked flatbreads with cheese and dates on top of their battle shields[19][20] and the ancient Greeks supplemented their bread with oils, herbs, and cheese.[21][22] An early reference to a pizza-like food occurs in the Aeneid, when Celaeno, queen of the Harpies, foretells that the Trojans would not find peace until they are forced by hunger to eat their tables (Book III). In Book VII, Aeneas and his men are served a meal that includes round cakes (like pita bread) topped with cooked vegetables. When they eat the bread, they realize that these are the "tables" prophesied by Celaeno.[23]

In the 16th century, Italian chef Bartolomeo Scappi's recipe collection there are recipes for pizzas made with puff pastry layers that include sugar and other sweet and savority ingredients. A 19th century recipe for pizza alla napoletana is made with almonds, vanilla and short pastry, and is topped with icing sugar.[24]

Modern pizza evolved from similar flatbread dishes in Naples, Italy, in the 18th or early 19th century.[25] Prior to that time, flatbread was often topped with ingredients such as garlic, salt, lard, and cheese. It is uncertain when tomatoes were first added and there are many conflicting claims.[25] Until about 1830, pizza was sold from open-air stands and out of pizza bakeries.

A popular contemporary legend holds that the archetypal pizza, pizza Margherita, was invented in 1889, when the Royal Palace of Capodimonte commissioned the Neapolitan pizzaiolo (pizza maker) Raffaele Esposito to create a pizza in honor of the visiting Queen Margherita. Of the three different pizzas he created, the Queen strongly preferred a pizza swathed in the colors of the Italian flag — red (tomato), green (basil), and white (mozzarella). Supposedly, this kind of pizza was then named after the Queen,[26] although later research cast doubt on this legend.[27] An official letter of recognition from the Queen's "head of service" remains on display in Esposito's shop, now called the Pizzeria Brandi.[28]

Pizza was brought to the United States with Italian immigrants in the late nineteenth century[29] and first appeared in areas where Italian immigrants concentrated. The country's first pizzeria, Lombardi's, opened in 1905.[30] Following World War II, veterans returning from the Italian Campaign, who were introduced to Italy's native cuisine, proved a ready market for pizza in particular.[31]

Preparation

Pizza is sold fresh or frozen, and whole or as portion-size slices or pieces. Methods have been developed to overcome challenges such as preventing the sauce from combining with the dough and producing a crust that can be frozen and reheated without becoming rigid. There are frozen pizzas with raw ingredients and self-rising crusts.

Another form of uncooked pizza is available from take and bake pizzerias. This pizza is assembled in the store, then sold to customers to bake in their own ovens. Some grocery stores sell fresh dough along with sauce and basic ingredients, to complete at home before baking in an oven.

- Pizza preparation

A wrapped, mass-produced frozen pizza to be cooked at home

A wrapped, mass-produced frozen pizza to be cooked at home

Traditional pizza dough being tossed

Traditional pizza dough being tossed_First_Class_Association_prepare_and_put_toppings_on_pizzas_in_the_galley_as_part_of_a_special_dinner_prepared_for_the_crew.jpg) Various toppings being placed on pan pizzas

Various toppings being placed on pan pizzas An uncooked Neapolitan pizza on a metal peel, ready for the oven

An uncooked Neapolitan pizza on a metal peel, ready for the oven

Cooking

In restaurants, pizza can be baked in an oven with stone bricks above the heat source, an electric deck oven, a conveyor belt oven, or, in the case of more expensive restaurants, a wood or coal-fired brick oven. On deck ovens, pizza can be slid into the oven on a long paddle, called a peel, and baked directly on the hot bricks or baked on a screen (a round metal grate, typically aluminum). Prior to use, a peel may be sprinkled with cornmeal to allow pizza to easily slide onto and off of it.[32] When made at home, it can be baked on a pizza stone in a regular oven to reproduce the effect of a brick oven. Cooking directly in a metal oven results in too rapid heat transfer to the crust, burning it.[33] Aficionado home-chefs sometimes use a specialty wood-fired pizza oven, usually installed outdoors. Dome-shaped pizza ovens have been used for centuries,[34] which is one way to achieve true heat distribution in a wood-fired pizza oven. Another option is grilled pizza, in which the crust is baked directly on a barbecue grill. Greek pizza, like Chicago-style pizza, is baked in a pan rather than directly on the bricks of the pizza oven.

When it comes to preparation, the dough and ingredients can be combined on any kind of table. With mass production of pizza, the process can be completely automated. Most restaurants still use standard and purpose-built pizza preparation tables. Pizzerias nowadays can even opt for hi tech pizza preparation tables that combine mass production elements with traditional techniques.[35]

- Pizza cooking

Pizzas baking in a traditional wood-fired brick oven

Pizzas baking in a traditional wood-fired brick oven A pizza baked in a wood-fired oven, being removed with a wooden peel

A pizza baked in a wood-fired oven, being removed with a wooden peel A cooked pizza served at a New York pizzeria

A cooked pizza served at a New York pizzeria

Crust

The bottom of the pizza, called the "crust", may vary widely according to style, thin as in a typical hand-tossed Neapolitan pizza or thick as in a deep-dish Chicago-style. It is traditionally plain, but may also be seasoned with garlic or herbs, or stuffed with cheese. The outer edge of the pizza is sometimes referred to as the cornicione.[36] Pizza dough often contains sugar, both to help its yeast rise and enhance browning of the crust.[37]

Dipping sauce specifically for pizza was invented by American pizza chain Papa John's Pizza in 1984 and has since become popular when eating pizza, especially the crust.[38]

Cheese

Mozzarella is commonly used on pizza, with the highest quality buffalo mozzarella produced in the surroundings of Naples.[39] Eventually, other cheeses were used well as pizza ingredients, particularly Italian cheeses including provolone, pecorino romano, ricotta, and scamorza. Less expensive processed cheeses or cheese analogues have been developed for mass-market pizzas to produce desirable qualities like browning, melting, stretchiness, consistent fat and moisture content, and stable shelf life. This quest to create the ideal and economical pizza cheese has involved many studies and experiments analyzing the impact of vegetable oil, manufacturing and culture processes, denatured whey proteins, and other changes in manufacture. In 1997, it was estimated that annual production of pizza cheese was 1 million tonnes (1,100,000 short tons) in the U.S. and 100,000 tonnes (110,000 short tons) in Europe.[40]

Varieties

Italy

Authentic Neapolitan pizza (pizza napoletana) is made with San Marzano tomatoes, grown on the volcanic plains south of Mount Vesuvius, and mozzarella di bufala Campana, made with milk from water buffalo raised in the marshlands of Campania and Lazio.[41] This mozzarella is protected with its own European protected designation of origin.[41] Other traditional pizzas include pizza alla marinara, which is topped with marinara sauce and is supposedly the most ancient tomato-topped pizza,[42] pizza capricciosa, which is prepared with mozzarella cheese, baked ham, mushroom, artichoke, and tomato,[43] and pizza pugliese, prepared with tomato, mozzarella, and onions.[44]

A popular variant of pizza in Italy is Sicilian pizza (locally called sfincione or sfinciuni),[45][46] a thick-crust or deep-dish pizza originating during the 17th century in Sicily: it is essentially a focaccia that is typically topped with tomato sauce and other ingredients. Until the 1860s, sfincione was the type of pizza usually consumed in Sicily, especially in the Western portion of the island.[47] Other variations of pizzas are also found in other regions of Italy, for example pizza al padellino or pizza al tegamino, a small-sized, thick-crust, deep-dish pizza typically served in Turin, Piedmont.[48][49][50]

United States

13% of the United States population consumes pizza on any given day.[51] Pizza chains such as Domino's Pizza, Pizza Hut, and Papa John's, pizzas from take and bake pizzerias, and chilled or frozen pizzas from supermarkets make pizza readily available nationwide.

The first pizzeria in the U.S. was opened in New York City's Little Italy in 1905.[52] Common toppings for pizza in the United States include anchovies, ground beef, chicken, ham, mushrooms, olives, onions, peppers, pepperoni, pineapple, salami, sausage, spinach, steak, and tomatoes. Distinct regional types developed in the 20th century, including Buffalo,[53] California, Chicago, Detroit, Greek, New Haven, New York, and St. Louis styles.[54] These regional variations include deep-dish, stuffed, pockets, turnovers, rolled, and pizza-on-a-stick, each with seemingly limitless combinations of sauce and toppings.

Another variation is grilled pizza, created by taking a fairly thin, round (more typically, irregularly shaped) sheet of yeasted pizza dough, placing it directly over the fire of a grill, and then turning it over once the bottom has baked and placing a thin layer of toppings on the baked side.[55] Toppings may be sliced thin to ensure that they heat through, and chunkier toppings such as sausage or peppers may be precooked before being placed on the pizza.[56] Garlic, herbs, or other ingredients are sometimes added to the pizza or the crust to maximize the flavor of the dish.[57]

Grilled pizza was offered in the United States at the Al Forno restaurant in Providence, Rhode Island[58] by owners Johanne Killeen and George Germon in 1980. Although it was inspired by a misunderstanding that confused a wood-fired brick oven with a grill, grilled pizza did exist prior to 1980, both in Italy, and in Argentina where it is known as pizza a la parrilla.[59] It has become a popular cookout dish, and there are even some pizza restaurants that specialize in the style. The traditional style of grilled pizza employed at Al Forno restaurant uses a dough coated with olive oil,[58] strained tomato sauce, thin slices of fresh mozzarella, and a garnish made from shaved scallions, and is served uncut.[60] The final product can be likened to flatbread with pizza toppings.[58] Another Providence establishment, Bob & Timmy's Grilled Pizza, was featured in a Providence-themed episode of the Travel Channel's Man v. Food Nation in 2011.[61]

Argentina

Argentina, and more specifically Buenos Aires, received a massive Italian immigration at the turn of the 19th century. Immigrants from Naples and Genoa opened the first pizza bars, though over time Spanish residents came to own the majority of the pizza businesses.

Standard Argentine pizza has a thicker crust, called "media masa" (half dough) than traditional Italian style pizza and includes more cheese. Argentine gastronomy tradition, served pizza with fainá, which is a Genovese chick pea-flour dough placed over the piece of pizza, and moscato wine. The most popular variety of pizza is called "muzzarella" (mozzarella), similar to Neapolitan pizza (bread, tomato sauce and cheese) but made with a thicker "media masa" crust, triple cheese and tomato sauce, usually also with olives. It can be found in nearly every corner of the country; Buenos Aires is considered the city with the most pizza bars by person of the world.[62] Other popular varieties include jam, tomato slices, red pepper and longaniza. Two Argentine-born varieties of pizza with onion, are also very popular: fugazza with cheese and fugazzetta. The former one consists in a regular pizza crust topped with cheese and onions; the later has the cheese between two pizza crusts, with onions on top.[63][64]

Records

The world's largest pizza was prepared in Rome in December 2012, and measured 1,261 square meters (13,570 square feet). The pizza was named "Ottavia" in homage to the first Roman emperor Octavian Augustus, and was made with a gluten-free base.[65] The world's longest pizza was made in Fontana, California in 2017 and measured 1,930.39 meters (6,333 feet 3 1⁄2 inches).[66]

The world's most expensive pizza listed by Guinness World Records is a commercially available thin-crust pizza at Maze restaurant in London, United Kingdom, which costs GB£100. The pizza is wood fire-baked, and is topped with onion puree, white truffle paste, fontina cheese, baby mozzarella, pancetta, cep mushrooms, freshly picked wild mizuna lettuce, and fresh shavings of a rare Italian white truffle.[67]

There are several instances of more expensive pizzas, such as the GB£4,200 "Pizza Royale 007" at Haggis restaurant in Glasgow, Scotland, which is topped with caviar, lobster, and 24-carat gold dust, and the US$1,000 caviar pizza made by Nino's Bellissima pizzeria in New York City, New York.[68] However, these are not officially recognized by Guinness World Records. Additionally, a pizza was made by the restaurateur Domenico Crolla that included toppings such as sunblush-tomato sauce, Scottish smoked salmon, medallions of venison, edible gold, lobster marinated in cognac, and champagne-soaked caviar. The pizza was auctioned for charity in 2007, raising GB£2,150.[69]

In 2017, the world pizza market was $128 billion, and in the US it was $44 billion spread over 76,000 pizzerias.[70] Overall, 13% of the U.S. population aged 2 years and over consumed pizza on any given day.[71] A Technomic study concluded that 83% of consumers eat pizza at least once per month. According to PMQ in 2018 60.47% of respondents reported an increase in sales over the previous year. [72]

Health concerns

Some mass-produced pizzas by fast food chains have been criticized as having an unhealthy balance of ingredients. Pizza can be high in salt, fat, and food energy. The USDA reports an average sodium content of 5,101 mg per 36 cm (14 in) pizza in fast food chains.[73] There are concerns about negative health effects.[74] Food chains have come under criticism at various times for the high salt content of some of their meals.[75]

Frequent pizza eaters in Italy have been found to have a relatively low incidence of cardiovascular disease[76] and digestive tract cancers[77] relative to infrequent pizza eaters, although the nature of the association between pizza and such perceived benefits is unclear. Pizza consumption in Italy might only indicate adherence to traditional Mediterranean dietary patterns, which have been shown to have various health benefits.[77]

Some attribute the apparent health benefits of pizza to the lycopene content in pizza sauce,[78] which research indicates likely plays a role in protecting against cardiovascular disease and various cancers.[79]

National Pizza Month

National Pizza Month is an annual observance that occurs for the month of October in the United States and some areas of Canada.[80][81][82][83] This observance began in October 1984, and was created by Gerry Durnell, the publisher of Pizza Today magazine.[83] During this time, some people observe National Pizza Month by consuming various types of pizzas or pizza slices, or going to various pizzerias.[80]

Similar dishes

- Calzone and stromboli are similar dishes that are often made of pizza dough folded (calzone) or rolled (stromboli) around a filling.

- Panzerotti are similar to calzones, but fried rather than baked.

- "Farinata" or "cecina".[84] A Ligurian (farinata) and Tuscan (cecina) regional dish made from chickpea flour, water, salt, and olive oil. Also called socca in the Provence region of France. Often baked in a brick oven, and typically weighed and sold by the slice.

- The Alsatian Flammekueche[85] (Standard German: Flammkuchen, French: Tarte flambée) is a thin disc of dough covered in crème fraîche, onions, and bacon.

- Garlic fingers is an Atlantic Canadian dish, similar to a pizza in shape and size, and made with similar dough. It is garnished with melted butter, garlic, cheese, and sometimes bacon.

- The Anatolian Lahmajoun (Arabic: laḥm bi'ajīn; Armenian: lahmajoun; also Armenian pizza or Turkish pizza) is a meat-topped dough round. The base is very thin, and the layer of meat often includes chopped vegetables.[86]

- The Levantine Manakish (Arabic: ma'ujnāt) and Sfiha (Arabic: laḥm bi'ajīn; also Arab pizza) are dishes similar to pizza.

- The Macedonian Pastrmajlija is a bread pie made from dough and meat. It is usually oval-shaped with chopped meat on top of it.

- The Provençal Pissaladière is similar to an Italian pizza, with a slightly thicker crust and a topping of cooked onions, anchovies, and olives.

- Pizza bagel is a bagel with toppings similar to that of traditional pizzas.

- Pizza bread is a type of sandwich that is often served open-faced which consists of bread, tomato sauce, cheese,[87] and various toppings. Homemade versions may be prepared.

- Pizza sticks may be prepared with pizza dough and pizza ingredients, in which the dough is shaped into stick forms, sauce and toppings are added, and it is then baked.[88] Bread dough may also be used in their preparation,[89] and some versions are fried.[90]

- Pizza Rolls are a trade-marked commercial product.

- Okonomiyaki, a Japanese dish cooked on a hotplate, is often referred to as "Japanese pizza".[91]

- "Zanzibar pizza" is a street food served in Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania. It uses a dough much thinner than pizza dough, almost like filo dough, filled with minced beef, onions, and an egg, similar to Moroccan bestila.[92]

- Panizza is half a stick of bread (often baguette), topped with the usual pizza ingredients, baked in an oven.

Gallery

Chicago-style pizza — deep dish

Chicago-style pizza — deep dish A halved calzone

A halved calzone A tarte flambée

A tarte flambée A vegetarian pizza

A vegetarian pizza

Garlic fingers, the archetype of Canadian pizza

Garlic fingers, the archetype of Canadian pizza

- Argentine fugazzetta.

See also

- Antica Pizzeria Port'Alba

- List of baked goods – Wikipedia list article

- List of Italian dishes – Wikipedia list article

- List of pizza chains – Wikimedia list article

- List of pizza varieties by country – Wikimedia list article

- Matzah pizza

- Italian cuisine – Cuisine originating from Italy

- Pizza cake

- Pizza cheese

- Pizza in China

- Pizza delivery – Pizzeria service

- Pizza farm – Farm split into sections like a pizza split into slices

- Pizza saver

- Pizza strips

- Pizza theorem – Equality of areas of alternating sectors of a disk with equal angles through any interior point

- Sicilian pizza

References

- "144843". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Naylor, Tony (6 September 2019). "How to eat: Neapolitan-style pizza". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Godoy, Maria (13 January 2014). "Italians To New Yorkers: 'Forkgate' Scandal? Fuhggedaboutit". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Maiden, Martin. "Linguistic Wonders Series: Pizza is a German(ic) Word". yourDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2003-01-15.

- Miller, Hanna (April–May 2006). "American Pie". American Heritage Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Baofu, P. (2013). The Future of Post-Human Culinary Art: Towards a New Theory of Ingredients and Techniques. Cambridge Scholars Publisher. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4438-4484-0. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- "Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN)". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Official Journal of the European Union, Commission regulation (EU) No 97/2010 Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, 5 February 2010

- International Trademark Association, European Union: Pizza napoletana obtains "Traditional Speciality Guaranteed" status Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, 1 April 2010

- "Naples' pizza twirling wins Unesco 'intangible' status". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 2017-12-07. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2017-12-07. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- Salvatore Riciniello (1987) Codice Diplomatico Gaetano, Vol. I, La Poligrafica

- Babiniotis, Georgios (2005). Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας [Dictionary of Modern Greek] (in Greek). Lexicology Centre. p. 1413. ISBN 978-960-86190-1-2.

- "Pizza, at Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- "Pissa, Liddell and Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- "Pizza, at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- 'pizza', Online Etymology Dictionary"

- "Pizza". Garzanti Linguistica. De Agostini Scuola Spa. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- Perry, Charles (1991-06-20). "A Stone-Age Snack : History: Pizza topped with tomatoes, pepperoni and cheese is only 100 years old, if that. But the basic idea of pizza actually goes back thousands of years". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- "Pizza, A Slice of American History" Liz Barrett (2014), p.13

- "The Science of Bakery Products" W. P. Edwards (2007), p.199

- Talati-Padiyar, Dhwani (2014-03-08). Travelled, Tasted, Tried & Tailored: Food Chronicles. ISBN 978-1304961358. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- Buonassisi, Rosario (2000). Pizza: From its Italian Origins to the Modern Table. Firefly. p. 78.

- "Aeneas and Trojans fulfill Anchises' prophecy". Archived from the original on 2017-03-29.

- Ceccarini, Rosella (2011). Pizza and Pizza Chefs in Japan: A Case of Culinary Globalization. London: Brill. p. 21. ISBN 9789004194663.

- Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. London: Reaktion. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-86189-391-8.

- "Pizza Margherita: History and Recipe". Italy Magazine. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "Was margherita pizza really named after Italy's queen?". BBC Food. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- Hales, Dianne (2009-05-12). Sök på Google (in Swedish). ISBN 978-0767932110. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-86189-630-8.

- Nevius, Michelle; Nevius, James (2009). Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. New York: Free Press. pp. 194–95. ISBN 978-1416589976.

- Turim, Gayle. "A Slice of History: Pizza Through the Ages". History.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- Owens, Martin J. (2003). Make Great Pizza at Home. Taste of America Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-9744470-0-1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Chen, Angus (23 July 2018). "Pizza Physics: Why Brick Ovens Bake The Perfect Italian-Style Pie". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- "pizza oven kits". Californo. Archived from the original on 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- "Automated pizza preparation table". rotopizza.club. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Braimbridge, Sophie; Glynn, Joanne (2005). Food of Italy. Murdoch Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-74045-464-3. Archived from the original on 2016-06-14. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- DeAngelis, Dominick A. (December 1, 2011). The Art of Pizza Making: Trade Secrets and Recipes. The Creative Pizza Company. pp. 20–28. ISBN 978-0-9632034-0-3.

- Shrikant, Adit (2017-07-27). "How Dipping Sauce for Pizza Became Oddly Necessary". Eater. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Anderson, Sam (October 11, 2012). "Go Ahead, Milk My Day". The New York Times. NYTimes. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- Fox, Patrick F.; (); et al. (2000). Fundamentals of Cheese Science. Aspen Pub. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-8342-1260-2. Archived from the original on 2016-05-14.

- "Selezione geografica". Europa.eu.int. 2009-02-23. Archived from the original on 2005-02-18. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- "La vera storia della pizza napoletana". Biografieonline.it. 2013-05-20. Archived from the original on 2013-06-29. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Guides, Rough (2011-08-01). Rough Guide Phrasebook: Italian: Italian. Rough Guides. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4053-8646-3. Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Wine Enthusiast, Volume 21, Issues 1-7. Wine Enthusiast. 2007. p. 475.

- "What is Sicilian Pizza?". WiseGeek. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- Giorgio Locatelli (2012-12-26). Made In Sicily. ISBN 978-0-06-213038-9. Retrieved 2013-07-04.

- Gangi, Roberta (2007). "Sfincione". Best of Sicily Magazine. Archived from the original on 2014-04-02.

- "Torino: la riscoperta della pizza al padellino". Agrodolce. 2014-04-03. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- "Pizza al padellino (o tegamino): che cos'è?". Gelapajo.it. Archived from the original on 2015-12-10. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- "Beniamino, il profeta della pizza gourmet". Torino - Repubblica.it. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Rhodes, Donna G.; Adler, Meghan E.; Clemens, John C.; LaComb, Randy P.; Moshfegh, Alanna J. "Consumption of Pizza" (PDF). Food Surveys Research Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Otis, Ginger Adams (2010). New York City 7. Lonely Planet. p. 256. ISBN 978-1741795912. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- Bovino, Arthur (2018-08-13). "Is America's Pizza Capital Buffalo, New York?". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Pizza Garden: Italy, the Home of Pizza". CUIP Chicago Public Schools – University of Chicago Internet Project. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- Byrn, Anne (2007). What Can I Bring? Cookbook. Workman Publishing. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0761159520.

- Chandler, J. (2012). Simply Grilling: 105 Recipes for Quick and Casual Grilling. Thomas Nelson. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4016-0452-3. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Delpha, J.; Oringer, K. (2015). Grilled Pizza the Right Way: The Best Technique for Cooking Incredible Tasting Pizza & Flatbread on Your Barbecue Perfectly Chewy & Crispy Every Time. Page Street Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-62414-106-5.

- "Great Grilled Pizza". Cook's Illustrated. July 1, 2016. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- Spinetto, H. (2007). Pizzerías de valor patrimonial de Buenos Aires (in Spanish). Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico. p. 159. ISBN 978-987-1037-67-4.

- Dixler, Hillary (March 19, 2014). "The Grilled Pizza Margarita at Al Forno in Providence". Eater. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- "Providence Featured on Travel Channel's Man V. Food Nation". City of Providence. August 4, 2011. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- Leire Gómez (17 July 2015). "Buenos Aires: la ciudad de la pizza". Tapas Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Cecilia Acuña (26 June 2017). "La historia de la pizza argentina: ¿de dónde salió la media masa?". La Nación. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Los inventores de la fugazza con queso". Clarín. 12 February 2006. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Largest pizza". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "Longest pizza". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- "Most expensive pizza". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Shaw, Bryan (March 11, 2010). "Top Five Most Expensive Pizzas in The World". Haute Living. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- "Chef cooks £2,000 Valentine pizza". BBC News. 2007-02-14. Archived from the original on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- Hynum, Rick. "Pizza Power 2017 - A State of the Industry Report". PMQ Pizza Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Rhodes, Donna; et al. (February 2014). "Consumption of Pizza" (PDF). Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief No. 11. USDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "The 2019 Pizza Power Report: A State-of-the-Industry Analysis - PMQ Pizza Magazine". Archived from the original on 2019-09-19. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

- "Basic Report 21299". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. 2014-09-28. Archived from the original on 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- "Survey of pizzas". Food Standards Agency. 2004-07-08. Archived from the original on 2005-12-28. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- "Health | Fast food salt levels "shocking"". BBC News. 2007-10-18. Archived from the original on 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- S Gallus, A Tavani, and C La Vecchia. "Pizza and risk of acute myocardial infarction" Archived 2014-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2004, Retrieved on 18 January 2015

- Gallus, Silvano; Bosetti, Cristina; Negri, Eva; Talamini, Renato; Montella, Maurizio; Conti, Ettore; Franceschi, Silvia; La Vecchia, Carlo (2003). "Does pizza protect against cancer?". International Journal of Cancer. 107 (2): 283–284. doi:10.1002/ijc.11382. PMID 12949808.

- Bramley, Peter "Is Lycopene Benefitial to Human Health?" Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Phytochemistry, Volume 54, Issue 3, 1 June 2000, Pages 233–236, Retrieved on 5 October 2014

- Omoni, Adetayo O.; Aluko, Rotimi E. (2005). "The anti-carcinogenic and anti-atherogenic effects of lycopene: A review". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 16 (8): 344–350. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2005.02.002.

- Genovese, Peter (2013-05-13). Pizza City. p. 97. ISBN 9780813558691. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Lund, Joanna M. (2007). Pizza Anytime. p. 4. ISBN 9780399533112. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. Oxford University Press. 2013-01-31. p. 643. ISBN 9780199734962. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- "National Pizza Month". Pizza.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Brick Oven Cecina". Fornobravo.com. Archived from the original on 2006-10-16. Retrieved 2009-04-02.

- Helga Rosemann, Flammkuchen: Ein Streifzug durch das Land der Flammkuchen mit vielen Rezepten und Anregungen (Offenbach: Höma-Verlag, 2009).

- McKernan, Bethan (27 October 2016). "A 'pizza war' has broken out between Turkey and Armenia". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Adler, Karen; Fertig, Judith (2014). Patio Pizzeria. Running Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7624-4966-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- McNair, James (2000). James McNair's New Pizza. Chronicle Books. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8118-2364-7. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Magee, Elaine (2009). The Flax Cookbook. Da Capo Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7867-3062-9. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- Wilbur, Todd (1997). Top Secret Restaurant Recipes. Penguin. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4406-7440-2. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- "hanamiweb.com". Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Samuelsson, Marcus. "The Soul of a New Cuisine: A Discovery of the Foods and Flavors of Africa". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. New York: 2006.

Further reading

- "The Saveur Ultimate Guide to Pizza". Saveur. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Kliman, Todd (September 5, 2012). "Easy as pie: A Guide to Regional Pizza". The Washingtonian. Explanation of eight pizza styles: Maryland, Roman, "Gourmet" Wood-fired, Generic boxed, New York, Neapolitan, Chicago, and New Haven.

- Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-391-8. OCLC 225876066.

- Chudgar, Sonya (March 22, 2012). "An Expert Guide to World-Class Pizza". QSR Magazine. Retrieved October 16, 2012.* Raichlen, Steven (2008). The Barbecue! Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 381–384. ISBN 978-0761149446.

- Delpha, J.; Oringer, K. (2015). Grilled Pizza the Right Way. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-62414-106-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) 208 pages.