Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (Italian: [alesˈsandro ˈvɔlta]; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist, and pioneer of electricity and power[2][3][4] who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and the discoverer of methane. He invented the Voltaic pile in 1799, and reported the results of his experiments in 1800 in a two-part letter to the President of the Royal Society.[5][6] With this invention Volta proved that electricity could be generated chemically and debunked the prevalent theory that electricity was generated solely by living beings. Volta's invention sparked a great amount of scientific excitement and led others to conduct similar experiments which eventually led to the development of the field of electrochemistry.[6]

Alessandro Volta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 February 1745 |

| Died | 5 March 1827 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics and chemistry |

Volta also drew admiration from Napoleon Bonaparte for his invention, and was invited to the Institute of France to demonstrate his invention to the members of the Institute. Volta enjoyed a certain amount of closeness with the emperor throughout his life and he was conferred numerous honours by him.[1] Volta held the chair of experimental physics at the University of Pavia for nearly 40 years and was widely idolised by his students.[1]

Despite his professional success, Volta tended to be a person inclined towards domestic life and this was more apparent in his later years. At this time he tended to live secluded from public life and more for the sake of his family until his eventual death in 1827 from a series of illnesses which began in 1823.[1] The SI unit of electric potential is named in his honour as the volt.

Early life and works

Volta was born in Como, a town in present-day northern Italy, on 18 February 1745. In 1794, Volta married an aristocratic lady also from Como, Teresa Peregrini, with whom he raised three sons: Zanino, Flaminio, and Luigi. His father, Filippo Volta, was of noble lineage. His mother, Donna Maddalena, came from the family of the Inzaghis.[7]

In 1774, he became a professor of physics at the Royal School in Como. A year later, he improved and popularised the electrophorus, a device that produced static electricity. His promotion of it was so extensive that he is often credited with its invention, even though a machine operating on the same principle was described in 1762 by the Swedish experimenter Johan Wilcke.[2][8] In 1777, he travelled through Switzerland. There he befriended H. B. de Saussure.

In the years between 1776 and 1778, Volta studied the chemistry of gases. He researched and discovered methane after reading a paper by Benjamin Franklin of the United States on "flammable air". In November 1776, he found methane at Lake Maggiore,[9] and by 1778 he managed to isolate methane.[10] He devised experiments such as the ignition of methane by an electric spark in a closed vessel.

Volta also studied what we now call electrical capacitance, developing separate means to study both electrical potential (V) and charge (Q), and discovering that for a given object, they are proportional.[11] This is called Volta's Law of Capacitance, and for this work the unit of electrical potential has been named the volt.[11]

In 1779 he became a professor of experimental physics at the University of Pavia, a chair that he occupied for almost 40 years.[1]

Volta and Galvani

Luigi Galvani, an Italian physicist, discovered something he named, "animal electricity" when two different metals were connected in series with a frog's leg and to one another. Volta realised that the frog's leg served as both a conductor of electricity (what we would now call an electrolyte) and as a detector of electricity. He also understood that the frog's legs were irrelevant to the electric current, which was caused by the two differing metals.[12] He replaced the frog's leg with brine-soaked paper, and detected the flow of electricity by other means familiar to him from his previous studies. In this way he discovered the electrochemical series, and the law that the electromotive force (emf) of a galvanic cell, consisting of a pair of metal electrodes separated by electrolyte, is the difference between their two electrode potentials (thus, two identical electrodes and a common electrolyte give zero net emf). This may be called Volta's Law of the electrochemical series.

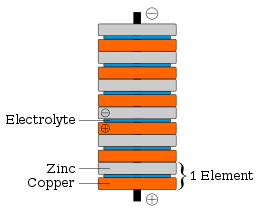

In 1800, as the result of a professional disagreement over the galvanic response advocated by Galvani, Volta invented the voltaic pile, an early electric battery, which produced a steady electric current.[13] Volta had determined that the most effective pair of dissimilar metals to produce electricity was zinc and copper. Initially he experimented with individual cells in series, each cell being a wine goblet filled with brine into which the two dissimilar electrodes were dipped. The voltaic pile replaced the goblets with cardboard soaked in brine.

Early battery

In announcing his discovery of the voltaic pile, Volta paid tribute to the influences of William Nicholson, Tiberius Cavallo, and Abraham Bennet.[14]

The battery made by Volta is credited as one of the first electrochemical cells. It consists of two electrodes: one made of zinc, the other of copper. The electrolyte is either sulfuric acid mixed with water or a form of saltwater brine. The electrolyte exists in the form 2H+ and SO42−. Zinc metal, which is higher in the electrochemical series than both copper and hydrogen, is oxidized to zinc cations (Zn2+) and creates electrons that move to the copper electrode. The positively charged hydrogen ions (protons) capture electrons from the copper electrode, forming bubbles of hydrogen gas, H2. This makes the zinc rod the negative electrode and the copper rod the positive electrode. Thus, there are two terminals, and an electric current will flow if they are connected. The chemical reactions in this voltaic cell are as follows:

- Zinc:

- Zn → Zn2+ + 2e−

- Sulfuric acid:

- 2H+ + 2e− → H2

Copper metal does not react, but rather it functions as an electrode for the electric current. Sulfate anion (SO42-) does not undergo any chemical reaction either, but migrates to the zinc anode to compensate for the charge of the zinc cations formed there. However, this cell also has some disadvantages. It is unsafe to handle, since sulfuric acid, even if diluted, can be hazardous. Also, the power of the cell diminishes over time because the hydrogen gas is not released. Instead, it accumulates on the surface of the copper electrode and forms a barrier between the metal and the electrolyte solution.

Last years and retirement

.jpeg)

In 1809 Volta became associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.[15] In honour of his work, Volta was made a count by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1810.[2]

Volta retired in 1819 to his estate in Camnago, a frazione of Como, Italy, now named "Camnago Volta" in his honour. He died there on 5 March 1827, just after his 82nd birthday.[16] Volta's remains were buried in Camnago Volta.[17]

Legacy

Volta's legacy is celebrated by the Tempio Voltiano memorial located in the public gardens by the lake. There is also a museum which has been built in his honour, which exhibits some of the equipment that Volta used to conduct experiments.[18] Nearby stands the Villa Olmo, which houses the Voltian Foundation, an organization promoting scientific activities. Volta carried out his experimental studies and produced his first inventions near Como.[19]

His image was depicted on the Italian 10,000 lire note (1990–1997) along with a sketch of his voltaic pile.[20]

In late 2017, Nvidia announced a new workstation-focused microarchitecture called Volta, succeeding Pascal and preceding Turing. The first graphics cards featuring Volta were released in December 2017, with two more cards releasing over the course of 2018.

Religious beliefs

Volta was raised as a Catholic and for all of his life continued to maintain his belief.[21] Because he was not ordained a clergyman as his family expected, he was sometimes accused of being irreligious and some people have speculated about his possible unbelief, stressing that "he did not join the Church",[22] or that he virtually "ignored the church's call".[23] Nevertheless, he cast out doubts in a declaration of faith in which he said:

I do not understand how anyone can doubt the sincerity and constancy of my attachment to the religion which I profess, the Roman, Catholic and Apostolic religion in which I was born and brought up, and of which I have always made confession, externally and internally. I have, indeed, and only too often, failed in the performance of those good works which are the mark of a Catholic Christian, and I have been guilty of many sins: but through the special mercy of God I have never, as far as I know, wavered in my faith... In this faith I recognise a pure gift of God, a supernatural grace; but I have not neglected those human means which confirm belief, and overthrow the doubts which at times arise. I studied attentively the grounds and basis of religion, the works of apologists and assailants, the reasons for and against, and I can say that the result of such study is to clothe religion with such a degree of probability, even for the merely natural reason, that every spirit unperverted by sin and passion, every naturally noble spirit must love and accept it. May this confession which has been asked from me and which I willingly give, written and subscribed by my own hand, with authority to show it to whomsoever you will, for I am not ashamed of the Gospel, may it produce some good fruit![24][25]

Publications

- De vi attractiva ignis electrici (1769) (On the attractive force of electric fire)

See also

References

- Munro, John (1902). Pioneers of Electricity; Or, Short Lives of the Great Electricians. London: The Religious Tract Society. pp. 89–102.

- Pancaldi, Giuliano (2003). Volta, Science and Culture in the Age of Enlightenment. Princeton Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12226-7.

- Alberto Gigli Berzolari, "Volta's Teaching in Como and Pavia" - Nuova voltiana

- Hall of Fame, Edison.

- "Milestones:Volta's Electrical Battery Invention, 1799". ieeeghn.org. IEEE Global History Network. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Enterprise and electrolysis". rsc.org. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Life and works". Alessandrovolta.info. Como, Italy: Editoriale srl. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Joh. Carl Wilcke (1762) "Ytterligare rön och försök om contraira electriciteterne vid laddningen och därtil hörande delar" (Additional findings and experiments on the opposing electric charges [that are created] during charging, and parts related thereto) Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar (Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Science Academy), vol. 23, pages 206–229, 245–266.

- Alessandro Volta, Lettere del Signor Don Alessandro Volta … Sull' Aria Inflammabile Nativa delle Paludi [Letters of Signor Don Alessandro Volta … on the flammable native air of the marshes] (Milan, (Italy): Giuseppe Marelli, 1777).

- Methane. BookRags. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Williams, Jeffrey Huw (2014). Defining and Measuring Nature: The Make of All Things. Morgan & Claypool. ISBN 978-1-627-05278-8.

- Price, Derek deSolla (1982). On the Brink of Tomorrow: Frontiers of Science. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society. pp. 16–17.

- Robert Routledge (1881). A popular history of science (2nd ed.). G. Routledge and Sons. p. 553. ISBN 0-415-38381-1.

- Elliott, P. (1999). "Abraham Bennet F.R.S. (1749–1799): a provincial electrician in eighteenth-century England" (PDF). Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 53 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1999.0063.

- "Alessandro G.A.A. Volta (1745–1827)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Volta". Institute of Chemistry - Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- For a photograph of his gravesite, and other Volta locales, see "Volta's localities". Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- Graham-Cumming, John (2009). "Tempio Voltiano, Como, Italy". The Geek Atlas: 128 Places Where Science and Technology Come Alive. O'Reilly Media. p. 95. ISBN 9780596523206.

- "Villa Olmo". centrovolta.it. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009.

- Desmond, Kevin (2016). Innovators in Battery Technology: Profiles of 95 Influential Electrochemists. McFarland. p. 235. ISBN 9781476622781.

- "Gli scienziati cattolici che hanno fatto lItalia (Catholic scientists who made Italy)". Zenit. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- 'Adam-Hart Davis. (2012). Engineers. Penguin. p. 138

- Michael Brian Schiffer (2003), Draw the Lightning Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of Enlightenment. University of California Press. p. 55

- Kneller, Karl Alois, Christianity and the leaders of modern science; a contribution to the history of culture in the nineteenth century (1911), p. 117–118

- Alessandro Volta. 1955. Epistolario, Volume 5. Zanichelli. p. 29

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alessandro Volta. |

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Volta and the "Pile"

- Alessandro Volta Google Doodle

- Alessandro Volta

- Count Alessandro Volta

- Alessandro Volta (1745–1827)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 198.

- Electrical units history.

- References to Volta in European historic newspapers

- Life of Alessandro Volta: Biography; Inventions; Facts