Il Canto degli Italiani

"Il Canto degli Italiani" (Italian pronunciation: [il ˈkanto deʎʎ itaˈljaːni];[1] "The Song of Italians") is a canto written by Goffredo Mameli and set to music by Michele Novaro in 1847[2], and is the current national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as the Inno di Mameli ([ˈinno di maˈmɛːli], "Mameli's Hymn"), after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d'Italia ([fraˈtɛlli diˈtaːlja], "Brothers of Italy"), from its opening line. The piece, a 4/4 in B-flat major, consists of six strophes and a refrain that is sung at the end of each strophe. The sixth group of verses, which is almost never performed, recalls the text of the first strophe.

| English: The Song of the Italians | |

|---|---|

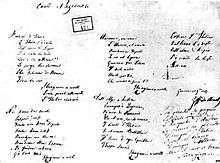

Holographic copy of 1847 of the Il Canto degli Italiani | |

National anthem of | |

| Also known as | Inno di Mameli (English: Mameli's Hymn) Fratelli d'Italia (English: Brothers of Italy) |

| Lyrics | Goffredo Mameli, 1847 |

| Music | Michele Novaro, 1847 |

| Adopted | 12 October 1946 (de facto) 4 December 2017 (de jure) |

| Preceded by | "La leggenda del Piave" |

| Audio sample | |

"Il Canto degli Italiani" (instrumental)

| |

The song was very popular during the unification of Italy and in the following decades, although after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (1861) the Marcia Reale (Royal March), the official hymn of the House of Savoy composed in 1831 by order of King Charles Albert of Sardinia, was chosen as the anthem of the Kingdom of Italy. The Il Canto degli Italiani was in fact considered too little conservative with respect to the political situation of the time: Fratelli d'Italia, of clear republican and Jacobin connotation, it was difficult to reconcile with the outcome of the unification of Italy, which was a monarchy.

After the Second World War, Italy became a republic, and the Il Canto degli Italiani was chosen, on 12 October 1946, as a provisional national anthem, a role that it later preserved while remaining the de facto anthem of the Italian Republic. Over the decades various parliamentary initiatives have taken place to make it the official national anthem, up to the law n ° 181 of 4 December 2017, which gave the Il Canto degli Italiani the status of a national anthem de jure.

History

Origins

The text of the Il Canto degli Italiani was written by the Genoese Goffredo Mameli, then a young student and a fervent patriot, in a historical context characterized by that widespread patriotism that already heralded the revolutions of 1848 and the First Italian War of Independence (1848-1849).[3]

On the precise date of the drafting of the text, the sources differ: according to some scholars, the hymn was written by Mameli on 10 September 1847[4], while according to others the date of birth of the composition was two days before, 8 September.[5]

After having discarded the idea of adapting it to existing music[6], 10 November 1847[7] Goffredo Mameli sent the text of the hymn to Turin to set it to music by the Genoese composer Michele Novaro, who was in the house at that time of the patriot Lorenzo Valerio[4][6][8].

Novaro was immediately conquered and, on 24 November 1847, he decided to set it to music[4]. Thus Anton Giulio Barrili, patriot and poet, remembered in April 1875, during a commemoration of Mameli, the words of Novaro on the birth of the music of the Il Canto degli Italiani[3]:

I placed myself at the harpsichord, with the verses of Goffredo on the lectern, and I strummed, murdered the poor instrument with convulsive fingers, always with eyes at the hymn, putting down melodic phrases, one above the other, but a thousand miles from the idea that they could adapt to those words. I stood up disgruntled with myself; I stayed a little longer in the Valerio house, but always with those verses before the eyes of the mind. I saw that there was no remedy, I took leave and ran home. There, without even taking off my hat, I threw myself at the piano. The motif strummed in the Valerio house came back to me: I wrote it on a sheet of paper, the first that came to my hands: in my agitation I turned the lamp over the harpsichord and, consequently, also on the poor sheet; this was the origin of the Fratelli d'Italia

— Michele Novaro

Mameli, who was Republican, Jacobin[9][10] and supporter of the motto born from the French Revolution liberté, égalité, fraternité[11], to write the text of the Il Canto degli Italiani was inspired by the French national anthem, La Marseillaise[12]. For example, "Stringiamci a coorte" recalls the verse of the La Marseillaise, "Formez vos bataillon" ("Form your battalions")[10].

In origin was, in the first version of the Canto degli Italiani, another verse that was dedicated to Italian women.[13] The verse, eliminated by Mameli himself before the official debut of the hymn, read[13][14]: "Tessete o fanciulle / bandiere e coccarde / fan l'alme gagliarde / l'invito d'amor.(Italian pronunciation: [tesˈseːte o fanˈtʃulle], [banˈdjɛːr(e) e kkokˈkarde], [fan ˈlalme ɡaʎˈʎarde], [liɱˈviːto daˈmor]]. English: Weave maidens / flags and cockades[N 1] / [they] make souls gallant the invitation of love)."

In the original version of the hymn, the first verse of the first verse read "Hurray Italy", Mameli then changed it to "Fratelli d'Italia" almost certainly at the suggestion of Michele Novaro himself[15]. The latter, when he received the manuscript, also added a rebellious "Yes!" At the end of the refrain sung after the last strophe[16][17].

Debut

10 December 1847 was an historical day for Italy[13]: the demonstration, organized in front of santuario della Nostra Signora di Loreto of the Genoese district of Oregina, was officially dedicated to the 101st anniversary of the popular rebellion of the Genoese quarter of Portoria during the War of the Austrian Succession which led to the expulsion of the Austrians from the city; in fact it was an excuse to protest against foreign occupations in Italy and induce Charles Albert of Sardinia to embrace the Italian cause of liberty and of unity.

On this occasion the flag of Italy was shown and Mameli's hymn was publicly sung for the first time. It was played by the Filarmonica Sestrese, then municipal band of Sestri Ponente, in front of a part of those 30 000 patriots - coming from all over Italy - who had come to Genoa for the event[6]. On 18 December 1847 the newspaper L'Italia of Pisa published this news from Turin:

[...] For many evenings numerous youths have come together in the Accademia filodrammatici to sing a hymn of Mameli, set to music by the maestro Novaro. Poetry ... is full of fire, music fully corresponds to it ... [...]

— Newspaper L'Italia, 18 December 1847, [18]

There was perhaps a previous public execution, of which the original documentation was lost, by the Filarmonica Voltrese founded by Nicola Mameli, brother of Goffredo[19], on 9 November 1847 in Genoa[20]. In this first public performance the first version of the Il Canto degli Italiani was sung, later modified in the definitive version[20]. Being its notoriously Mazzinian author, the piece was forbidden by the Savoy police until March 1848: its execution was also forbidden by the Austrian police, which also pursued its singing interpretation - considered a political crime - until the end of the First World War[21].

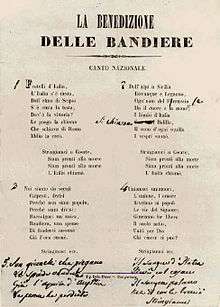

There are two autograph manuscripts up to the 21st century; the first, the original one linked to the first draft, with hand annotations by Mameli himself, is located at the Mazzinian Institute of Genoa[22], while the second, sent by Mameli on 10 November 1847 to Novaro, is kept at the Museo del Risorgimento in Turin[7]. The autograph manuscript that Novaro sent to the publisher Francesco Lucca is instead located in the Ricordi Historical Archive.[23] The sheet that is found at Istituto Mazziniano, subsequent to the two manuscripts, lacks the last strophe ("Son giunchi che piegano...") for fear of censorship. These leaflets were to be distributed at the 10 December demonstration, in Genoa.[24] The hymn was also printed on leaflets in Genoa, by the printing office Casamara.

The following decades

When the Il Canto degli Italiani debuted, there were only a few months left to the revolutions of 1848. Shortly before the promulgation of the Statuto Albertino, the constitution that Charles Albert of Sardinia conceded to the Kingdom of Sardinia in Italy on 4 March 1848, a coercive law had been abrogated that prohibited gatherings of more than ten people[6]. From this moment on, the Il Canto degli Italiani experienced a growing success thanks to its catchiness, which facilitated its diffusion among the population[6]. After 10 December the hymn spread all over the Italian peninsula, brought by the same patriots that participated in the Genoa demonstration[6]. In the 1848, Mameli's hymn was very popular among the Italian people and it was commonly sung during demonstrations, protests and revolts as a symbol of the Italian Unification in most parts of Italy[25].

When the Il Canto degli Italiani became popular, the Savoy authorities censored the fifth strophe[3], extremely harsh with the Austrians; however after the declaration of war to Austrian Empire and the beginning of the First Italian War of Independence (1848-1849)[26], the soldiers and the Savoy military bands performed it so frequently that King Charles Albert was forced to withdraw all censorship.[27] The anthem was in fact widespread, especially among the ranks of the Republican volunteers[28].

In the Five Days of Milan, the rebels sang the Il Canto degli Italiani during clashes against the Austrian Empire[29] and was sung frequently during the celebrations for the promulgation, by Charles Albert of Sardinia, of the Statuto Albertino (also in 1848).[30] Even the brief experience of the Roman Republic (1849) had, among the hymns most sung by the volunteers[31], the Il Canto degli Italiani[32], with Giuseppe Garibaldi who used to hum and whistle it during the defense of Rome and the flight to Venice[4]. In the 1860, the corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi used to sing the hymn in the battles against the Bourbons in Sicily and Southern Italy during the Expedition of the Thousand.[33] Giuseppe Verdi, in his Inno delle nazioni ("Hymn of the nations"), composed for the London International Exhibition of 1862, chose Il Canto degli Italiani to represent Italy, putting it beside God Save the Queen and La Marseillaise.

From the unification of Italy to the First World War

After the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (1861) the Marcia Reale ("Royal March")[34], composed in 1831, was chosen as the national anthem of unified Italy: the decision was taken because the Il Canto degli Italiani, which had too little conservative contents and was characterized by a strong republican imprint and Jacobin[9][10], did not combine with the epilogue of the unification of Italy, of monarchical origin[26]. The references to the republican creed of Mameli - which was in fact Mazzinian - were, however, more historical than political[10]; on the other hand, the Il Canto degli Italiani was disliked also by the socialist and anarchist circles, which considered it instead the opposite, that is too little revolutionary[35].

The song was one of the most common songs during the Third Italian War of Independence (1866)[26], and even the Capture of Rome on 20 September 1870, the last part of the Italian unification, was accompanied by choirs that sang it together with Bella Gigogin and the Marcia Reale[34][36]; on this occasion, the Il Canto degli Italiani was often performed also by the fanfare of the Bersaglieri.[37]

Even after the end of the Italian unification the Il Canto degli Italiani, which was taught in schools, remained very popular among Italians[38], but it was joined by other musical pieces that were connected to the political and social situation of the time as, for example, the Inno dei lavoratori ("Hymn of the workers") or Goodbye to Lugano[39], which partly obscured the popularity of the hymns used during Italian unification (including the Il Canto degli Italiani), since they had a meaning more related to everyday problems.[40]

Fratelli d'Italia, thanks to references to patriotism and armed struggle[40], returned to success during the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), where he joined A Tripoli[41], and in the trenches of the First World War (1915-1918)[40]: the Italian irredentism that characterized it indeed found a symbol in the Il Canto degli Italiani, although in the years following the last war context cited he would have been preferred, in the patriotic ambit, musical pieces of greater military style such as La Leggenda del Piave, the Canzone del Grappa or La campana di San Giusto[35]. Shortly after Italy entered the war in the First World War, on 25 July 1915, Arturo Toscanini performed the Il Canto degli Italiani during an interventionist demonstration[42][43].

During fascism

After the march on Rome (1922) the purely fascist chants such as Giovinezza (or Inno Trionfale del Partito Nazionale Fascista) took on great importance[44], which were widely disseminated and publicized, as well as taught in schools, although they were not official hymns[45]. In this context the non-fascist melodies were discouraged, and the Il Canto degli Italiani was not an exception[40]. In 1932 the secretary of the National Fascist Party Achille Starace decided to prohibit the musical pieces that did not sing to Benito Mussolini and, more generally, those not directly linked to fascism[46].

Thus the tracks judged to be subversive, ie those of anarchist or socialist type, such as the hymn of the workers or The Internationale, and the official hymns of foreign nations not sympathizing with fascism, such as La Marseillaise[47], were banned. After the signing of the Lateran Treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See (1929), anti-clerical passages were also banned[47]. The chants used during the Italian unification were however tolerated[35][47]: the Il Canto degli Italiani, which was forbidden in official ceremonies, was granted a certain condescension only on particular occasions[47].

In the spirit of this directive, for example, songs such as the Nazi hymn Horst-Wessel-Lied and the Francoist song Cara al Sol were encouraged, as they are official musical pieces from regimes akin to that led by Benito Mussolini[47]. Otherwise, some songs were resized, such as La leggenda del Piave, sung almost exclusively during the National Unity and Armed Forces Day every 4 November[48].

During the Second World War, fascist pieces composed by regime musicians were released, also via radio: there were very few songs spontaneously born among the population[49]. In the years of the second war were common songs like A primavera viene il bello, Battaglioni M, Vincere! and Camerata Richard, while, among the spontaneously born songs, the most famous was On the Sul ponte di Perati[50].

After the armistice of 8 September 1943, the Italian government provisionally adopted as a national anthem, replacing the Marcia Reale, La leggenda del Piave[35][51][52]: the Italian monarchy had in fact been questioned for having allowed the establishment of the fascist dictatorship[35]; recalling the Italian victory in the First World War, it could infuse courage and hope to the troops of the Royal Italian Army who fought the Italian Social Republic of Benito Mussolini and the Nazi Germany[53].

In this context, Fratelli d'Italia, along with other songs used during Italian unification and partisan songs, resounded in Southern Italy freed by the Allies and in the areas controlled by the partisans north of the war front[54]. The Il Canto degli Italiani, in particular, had a good success in anti-fascist circles[48], where it joined the partisan songs Fischia il vento and Bella ciao[35][54]. Some scholars believe that the success of the piece in anti-fascist circles was then decisive for its choice as a provisional anthem of the Italian Republic[42].

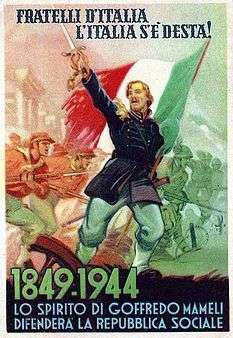

Often the Il Canto degli Italiani is wrongly referred to as the national anthem of the Italian Social Republic of Benito Mussolini. However, the lack of an official national anthem of the Republic of Mussolini is documented: in fact, the Il Canto degli Italiani or Giovinezza[55] was performed in the ceremonies. The Il Canto degli Italiani and - more generally - the themes referring to unification of Italy were used by the Republic of Mussolini, with a change of course compared to the past, for propaganda purposes only.[56]

So Mameli's hymn was, curiously, sung by both the Italian partisans and the people who supported the Italian Social Republic (fascists).[57]

From provisional to official anthem

In 1945, at the end of the war, Arturo Toscanini directed the execution of the Inno delle nazioni in London, composed by Giuseppe Verdi in 1862 and including the Il Canto degli Italiani[3][58]; however, as a provisional national anthem, even after the birth of the Italian Republic, La leggenda del Piave[59] was temporarily confirmed.

For the choice of the national anthem a debate was opened which identified, among the possible options: the Va, pensiero from Giuseppe Verdi's Nabucco, the drafting of a completely new musical piece, the Il Canto degli Italiani, the Inno di Garibaldi and the confirmation of the La Leggenda del Piave[59][60]. The political class of the time then approved the proposal of the War Minister Cipriano Facchinetti, who foresaw the adoption of the Il Canto degli Italiani as a provisional anthem of the State[60].

The La Leggenda del Piave then had the function of national anthem of the Italian Republic until the Council of Ministers of 12 October 1946, when Cipriano Facchinetti (of republican political belief), officially announced that during the oath of the Armed Forces of 4 November, as provisional anthem, the Il Canto degli Italiani would have been adopted[61][62]. The press release stated that[63]:

[...] On the proposal of the Minister of War it was established that the oath of the Armed Forces to the Republic and to its Chief would be carried out on November 4th p.v. and that, temporarily, the anthem of Mameli is adopted as the national anthem [...]

— Cipriano Facchinetti

Facchinetti also declared that a draft decree would be proposed which would confirm the Il Canto degli Italiani provisional national anthem of the newly formed Republic, an intention which, however, was not followed up[62].[64]

Facchinetti proposed to formalize the Il Canto degli Italiani in the Constitution of Italy, in preparation at that time, but without success[60]. The Constitution, which came into force in 1948, sanctioned, in article 12, the use of the flag of Italy as a national flag, but did not establish what the national anthem would be, nor even the national symbol of Italy, which was later adopted by legislative decree dated 5 May 1948.[65]

.jpg)

A draft constitutional law prepared in the immediate post-war period whose final objective was the insertion, in article 12, of the paragraph "The Anthem of the Republic is the Il Canto degli Italiani" was not followed, as well as the hypothesis of a decree presidential election that issued a specific regulation[66]

The Il Canto degli Italiani then had a great success among Italian emigrants[67]: scores of Fratelli d'Italia can be found, together with the flag of Italy, in many shops of the various Little Italy scattered in the Anglosphere. The Il Canto degli Italiani is often played on more or less official occasions in North and South America[67]: in particular, it was the "soundtrack" of the fundraisers destined to the Italian population leaving devastated by the conflict, which were organized in the second post-war period in the Americas[68].

It was the President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, in charge from 1999 to 2006, to activate a work of valorisation and re-launch of the Il Canto degli Italiani as one of the national symbol of Italy[69][70]. With reference to the Il Canto degli Italiani, Ciampi declared that[70]:

[...] It is a hymn that, when you listen to it, makes you vibrate inside; it is a song of freedom of a people that, united, rises again after centuries of divisions, of humiliations [...]

— Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

In August 2016 a bill was submitted to the Constitutional Affairs Committee of the Chamber of Deputies to make the Canto degli Italiani an official hymn of the Italian Republic.[71] In July 2017 the committee approved this bill.[72] On 15 December 2017, the publication in the Gazzetta Ufficiale of the law nº 181 of 4 December 2017, which came into force on 30 December 2017.[73]

Lyrics

This is the complete text of the original poem written by Goffredo Mameli. However, the Italian anthem, as commonly performed in official occasions, is composed of the first strophe sung twice, and the chorus, then ends with a loud "Sì!" ("Yes!").

The first strophe presents the personification of Italy who is ready to go to war to become free, and shall be victorious as Rome was in ancient times, "wearing" the helmet of Scipio Africanus who defeated Hannibal at the final battle of the Second Punic War at Zama; there is also a reference to the ancient Roman custom of slaves who used to cut their hair short as a sign of servitude, hence the Goddess of Victory must cut her hair in order to be slave of Rome (to make Italy victorious).[74]

In the second strophe the author complains that Italy has been a divided nation for a long time, and calls for unity; in this strophe Goffredo Mameli uses three words taken from the Italian poetic and archaic language: calpesti (modern Italian: calpestati), speme (modern speranza), raccolgaci (modern ci raccolga).

The third strophe is an invocation to God to protect the loving union of the Italians struggling to unify their nation once and for all. The fourth strophe recalls popular heroic figures and moments of the Italian fight for independence such as the battle of Legnano, the defence of Florence led by Ferruccio during the Italian Wars, the riot started in Genoa by Balilla, and the Sicilian Vespers. The last strophe of the poem refers to the part played by Habsburg Austria and Czarist Russia in the partitions of Poland, linking its quest for independence to the Italian one.[3]

Italian lyrics |

Phonetic transcription (IPA) |

English translation |

Fratelli d'Italia, |

[fraˈtɛlli diˈtaːlja |] [lˈitaːlja ˌsɛ dˈdesta |] [delˈlelmo di ʃˈʃiːpjo] [ˌsɛ tˈtʃinta la ˈtɛsta ǁ] [doˈvɛ lla vitˈtɔːrja |] [le ˈpɔrɡa la ˈkjɔːma |] [ke ˈskjaːva di ˈroːma] [idˈdiːo la kreˈɔ ǁ] |

|

Stringiamci a coorte, |

[strinˈdʒantʃ a kkoˈorte |] [ˌsjam ˈprontj alla ˈmɔrte ǁ] [ˌsjam ˈprontj alla ˈmɔrte |] [liˈtaːlja kjaˈmɔ ǁ] [strinˈdʒamtʃ a kkoˈorte |] [ˌsjam ˈprontj alla ˈmɔrte ǁ] [ˌsjam ˈprontj alla ˈmɔrte |] [liˈtaːlja kjaˌmɔ ǁ ˈsi ǁ] |

|

Noi fummo da secoli[N 14] |

[ˌnoi ˈfummo da (s)ˈsɛːkoli] [kalˈpesti | deˈriːzi |] [perˈke nnon ˌsjam ˈpɔːpolo |] [perˈke sˌsjam diˈviːzi ǁ] [rakˈkɔlɡatʃ uˈnuːnika] [banˈdjɛːra (|) una ˈspɛːme |] [di ˈfondertʃ inˈsjɛːme] [ˌdʒa lˈloːra swoˈnɔ ǁ] |

|

Uniamoci, amiamoci, |

[uˈnjaːmotʃ(i |) aˈmjaːmotʃi |] [luˈnjoːn(e) e llaˈmoːre] [riˈveːlano ai ˈpɔːpoli] [le ˈviːe del siɲˈɲoːre ǁ] [dʒuˈrjaːmo far ˈliːbero] [il ˈswɔːlo naˈtiːo |] [uˈniːti | per ˈdiːo |] [ˌki vˈvintʃer tʃi ˈpwɔ ǁ] |

|

Dall'Alpi a Sicilia |

[dalˈlalpj a ssiˈtʃiːlja] [doˈvuŋkw(e) ˌɛ lleɲˈɲaːno |] [oɲˈɲwɔm di ferˈruttʃo] [ˌa il ˈkɔːre | ˌa lla ˈmaːno |] [i ˈbimbi diˈtaːlja] [si ˈkjaːmam baˈlilla |] [il ˈswɔn ˌdoɲɲi ˈskwilla] [i ˈvɛspri swoˈnɔ ǁ] |

|

Son giunchi che piegano |

[ˌson ˈdʒuŋki ke pˈpjɛːɡano] [le ˈspaːde venˈduːte |] [ˌdʒa lˈlaːkwila ˈdaustrja] [le ˈpenne ˌa pperˈduːte ǁ] [il ˈsaŋɡwe diˈtaːlja |] [il ˈsaŋɡwe poˈlakko |] [beˈve | kol koˈzakko |] [ma il ˈkɔr le bruˈtʃɔ ǁ] |

The mercenary swords |

Music

.jpg)

Novaro's musical composition is written in a typical marching time (4/4)[75] in the key of B-flat major[76]. It has a catchy character and an easy melodic line that simplifies memory and execution.[75]

On the other hand, on the harmonic and rhythmic level, the composition presents a greater complexity, which is particularly evident from bar 31, with the important final modulation in the near tone of E-flat major, and with the agogic variation from the initial Allegro martial[77] to a more lively Allegro mosso, which results in an accelerando[75]. This second characteristic is well recognizable especially in the most accredited engravings of the autograph score.[78]

From a musical point of view, the piece is divided into three parts: the introduction, the strophes and the refrain.

The introduction consists of twelve bars, characterized by a dactyl rhythm that alternates one eighth note sixteenth note. The first eight bars present a bipartite harmonic succession between B flat major and G minor, alternating with the respective dominant chords (F major and D major seventh. This section is only instrumental. The last four bars, introducing the actual song, return to B flat.

The strophes therefore attack in B♭ and are characterized by the repetition of the same melodic unit, replicated in various degrees and at different pitch. Each melodic unit corresponds to a fragment of the Mamelian hexasyllable, whose emphatic rhythm enthused Novaro, who set it to music according to the classical scheme of dividing the verse into two parts ("Fratelli / d'Italia / Italia / s'è desta").[79]

However, there is also an unusual choice, since the usual leap of a correct interval does not correspond to the anacrusic rhythm: on the contrary, the verses «Fratelli / d'Italia» and «dell'elmo / di Scipio» carry each one, at the beginning, two identical notes (F o D depending on the case). This partly weakens the accentuation of the syllable in beat to the advantage of the upbeat one, and produces audibly a syncopated effect, contrasting the natural short-long succession of the paroxytone verse.[79]

On the strong tempo of the basic melodic unit we perform an unequal group of pointed eighth note and sixteenth note.

Some musical re-readings of the Il Canto degli Italiani intended to give greater prominence to the melodic aspect of the song, and have therefore softened this rhythmic scan bringing it closer to that of two notes of the same duration (eighth note)[77].

At bar 31, again with an unusual choice[80], the key changes to E flat major until the end of the melody[81], yielding only to the relative minor in the performance of the tercet "Stringiamci a coorte /siam pronti alla morte / L'Italia chiamò"[80], while time becomes an Allegro mosso. Also the refrain is characterized by a melodic unit replicated several times; dynamically, in the last five bars it grows in intensity, passing from pianissimo to forte and to fortissimo with the indication crescendo e accelerando sino alla fine ("growing and accelerating to the end").[82]

Recordings

The copyrights have already lapsed as the work is in the public domain the two authors having been dead for more than 70 years. Novaro never asked for compensation for printing music, ascribing his work to the patriotic cause; to Giuseppe Magrini, who made the first print of the Il Canto degli Italiani, asked only for a certain number of printed copies for personal use. In 1859, Novaro, at Tito Ricordi's request to reprint the text of the song with his publishing house, ordered that the money be directly paid in favor of a subscription for Giuseppe Garibaldi[83].

The score of the Il Canto degli Italiani is instead owned by the publisher Sonzogno[84], which therefore has the possibility of making the official prints of the piece[22].

The oldest known sound document of the Il Canto degli Italiani (disc at 78 rpm for gramophone, 17 cm in diameter) is dated 1901 and was recorded by the Municipal Band of Milan under the direction of Pio Nevi.[85]

One of the first recordings of Fratelli d'Italia was that of 9 June 1915, which was performed by the Neapolitan opera and music singer Giuseppe Godono.[86] The label for which the song was recorded was the Phonotype of Naples.[87]

Another ancient etching received is that of the Gramophone Band, recorded in London for His Master's Voice on 23 January 1918.[88]

During the events

Over the years a public ceremonial has been established for its execution, which is still in force[89]. According to the label, during his execution, the soldiers must present their weapons, while the officers must stand at attention[89]. Civilians, if they wish, can also put themselves to attention.[90]

According to the ceremonial, on the occasion of official events, only the first two strophes should be performed without the introduction[63][89]. If the event is institutional, and a foreign hymn must also be performed, this is played first as an act of courtesy[89].

In 1970 the obligation, however, remained almost always unfulfilled, to execute the Ode to Joy of Ludwig van Beethoven, that is the official anthem of Europe, whenever the Il Canto degli Italiani is played[89].

Notes

- It alludes to the flag of Italy and to the cockade of Italy, both symbols of the battle for the unification of Italy.

- The Italians belong to a single people and are therefore "brothers"

- "Italy has woken up", that is, it is ready to fight.

- Scipio Africanus, winner of Battle of Zama, is brought as an example for the ability of the Roman Republic to recover from the defeat and fight valiantly and victoriously against the enemy.

- Scipione's helmet, which Italy has now worn, is a symbol of the impending struggle against the Austrian Empire oppressor

- The goddess Victoria. For a long time the goddess Vittoria was closely linked to ancient Rome, but now she is ready to dedicate herself to the new Italy for the series of wars that are necessary to drive the foreigner out of the national soil and to unify the country.

- Le porga la chioma can also be more literally translated as "Let her tender her hair to Rome" or "Tender her hair". Here the poet refers to the use, in ancient Rome, of cutting hair to slaves to distinguish them from free women who instead wore long hair. So the Victory must turn the hair to Italy to be cut off and become "slave" of it.

- The sense is that ancient Rome made, with its conquests, the goddess Victoria "its slave".

- Ancient Rome was great by God's design.

- The phrase can also be translated more literally as "Let us tighten in a cohort". The cohort (in Latin cohors, cohortis) was a combat unit of the Roman army, tenth part of a Roman legion. This very strong military reference, reinforced by the appeal to the glory and military power of ancient Rome, once again calls all men to arms against the oppressor.

- Siam pronti alla morte may be understood both as an indicative ("We are ready to die") and as an imperative ("Let us be ready to die").

- It alludes to the call to arms of the Italian people with the aim of driving out the foreign ruler from national soil and unifying Italy, still divided into pre-unification states.

- Although the final exclamation, "Yes!", is not included in the original text, it is always used in all official occasions.

- A different tense may be found: Noi siamo da secoli, "We have been for centuries".

- Mameli underlines the fact that Italy, understood as an Italian peninsula, was not united. At the time, in fact, (1847) it was still divided into seven states. For this reason, Italy had for centuries been often treated as a land of conquest.

- The hope that Italy, still divided in the pre-unification states, will finally gather under a single flag, merging into one nation.

- The third verse, which is dedicated to the political thought of Giuseppe Mazzini, founder of Young Italy and Young Europe, incites the search for national unity through the help of divine providence and thanks to the participation of the entire Italian people finally united in an intent common.

- In the Battle of Legnano of 29 May 1176 the Lombard League defeated Frederick Barbarossa, here the event rises to symbolize the fight against foreign oppression. Legnano, thanks to the historic battle, is the only city, besides Rome, to be mentioned in the Italian national anthem.

- Francesco Ferruccio, symbol of the siege of Florence (2 August 1530), with which the troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, wanted to bring down the Republic of Florence to restore the Medici lordship. In this circumstance, the dying Ferruccio was cowardly finished with a stab by Fabrizio Maramaldo, a captain of fortune in the service of Carlo V. "Vile, you kill a dead man", were the famous words of infamy that the hero addressed to his killer.

- Nickname of Giovan Battista Perasso who on 5 December 1746 began, with the throwing of a stone, to an officer, to the Genoese revolt that ended with the chase of the Archduchy of Austria, who had occupied the city for several months.

- The Sicilian Vespers, the Easter Monday uprising of 1282 against the French extended to all of Sicily after having begun in Palermo, unleashed by the sound of all the bells of the city.

- Mercenaries, whose use is anachronistically attributed to Austrian Empire, not valiant as the patriotic heroes, but weak as rushes.

- Austrian Empire is in decline.

- Poland, too, had been invaded by Austrian Empire, which had been dismembered with the help of Russian Empire and Kingdom of Prussia. The fate of Poland is singularly linked to that of Italy. Also Poland's anthem (Dabrowski's Mazurca) was written in Italy and originally titled ″Song of the Polish Legions in Italy″.

- With the Russian Empire.

- A wish and an omen: the blood of oppressed peoples, who will rise up against Austrian Empire, will mark the end.

Citations

- (in Italian) DOP entry .

- "Italy – Il Canto degli Italiani/Fratelli d'Italia". NationalAnthems.me. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "L'Inno nazionale". Quirinale.it. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Caddeo, 1915 & p. 37.

- Associazione Nazionale Volontari di Guerra "Canti della Patria" in Il Decennale - X anniversario della Vittoria, Anno VII dell'era fascista, Vallecchi Editore, Firenze, 1928, p. 236

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 18.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 17.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 126.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 50.

- Ridolfi, 2003 & p. 149.

- Bassi, 2011 & p. 143.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 119.

- "Mameli, l'inno e il tricolore" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- Stramacci, 1991 & p. 57.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 121.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 20-21.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 127.

- Lincei, 2002 & p. 235.

- "Accadde Oggi: 10 dicembre" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 120.

- Caddeo, 1915 & pp. 37-38.

- Bassi, 2011 & p. 50.

- "La decisione di De Gasperi "Fratelli d'Italia è inno nazionale"" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Inno di Mameli – Il canto degli Italiani: testo, analisi e storia". labandadeisei.it. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 42.

- Ridolfi, 2003 & p. 147.

- "Come nacque l'inno di Mameli?" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 15.

- "IL CANTO DEGLI ITALIANI: il significato". Radiomarconi.com. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Concessione e promulgazione dello Statuto Albertino" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Caddeo, 1915 & p. 38.

- "L'inno della Repubblica Romana" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Il canto degli italiani – 150 anni di". Progettocentocin.altervista.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Bassi, 2011 & p. 46.

- Ridolfi, 2003 & p. 148.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 52.

- "La breccia di Porta Pia". 150anni-lanostrastoria.it. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 55.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 56-57.

- "Puntata di "Il tempo e la storia" su Il Canto degli Italiani" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 58.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 114.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 59-60.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 111.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 63.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 131.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 64.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 65.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 68.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 68-69.

- "E il ministro lodò il campano Giovanni Gaeta" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- "La Leggenda del Piave inno d'Italia dal 1943 al 1946" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 70.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 69.

- ""I canti di Salò" di Giacomo De Marzi". Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Fratelli d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "I canti di Salò". Archiviostorico.info. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Bassi, 2011 & p. 146.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 112.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 72.

- Bassi, 2011 & p. 47.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 110.

- "Inno nazionale" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "L'inno di Mameli: Un po' di storia" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "I simboli della Repubblica – L'emblema" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Lincei, 2002 & p. 34.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 125.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 126.

- Ridolfi, 2002 & p. 153.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 12.

- "L'inno di Mameli è ancora provvisorio. Proposta di legge per renderlo ufficiale" (in Italian).

- "Saranno ufficiali tutte e sei le strofe dell'Inno di Mameli e non solo le prime due" (in Italian). ANSA.it. 24 July 2017.

- "LEGGE 4 dicembre 2017, n. 181 – Gazzetta Ufficiale" (in Italian). 15 December 2017.

- "Il testo dell'Inno di Mameli. Materiali didattici di Scuola d'Italiano Roma a cura di Roberto Tartaglione" (in Italian). Scudit.net. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Vulpone, 2002 & p. 40.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 20.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 129.

- "Varie registrazioni del Canto degli Italiani" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 March 2015. See in particular the version of the Ensemble Coro di Torino directed by Maurizio Benedetti.

- Jacoviello, 2012 & pp. 117-119.

- NOVARO, Michele entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia italiana

- Calabrese, 2011 & pp. 129-130.

- Calabrese, 2011 & p. 130.

- Calabrese, 2011 & pp. 127-128.

- "Siae e Inno di Mameli" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Su RAI International la collezione di Domenico Pantaleone" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Inno alla vittoria" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "L'INNO DI MAMELI: DOCUMENTI E PROTAGONISTI" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ""Il Canto degli Italiani" di Goffredo Mameli e Michele Novaro" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 73.

- "Proposta di legge n. 4331 della XVI legislatura" (in Italian). Retrieved 15 October 2015.

References

- Bassi, Adriano (2011). Fratelli d'Italia: I grandi personaggi del Risorgimento, la musica e l'unità (in Italian). Paoline. ISBN 978-88-315-3994-4.

- Caddeo, Rinaldo (1915). Inni di Guerra e Canti patriottici del Popolo Italiano (in Italian). Casa Editrice Risorgimento. ISBN 1-178-22330-2.

- Calabrese, Michele (2011). "Il Canto degli Italiani: genesi e peripezie di un inno". Quaderni del Bobbio (in Italian). 3.

- Jacoviello, Stefano (2012). Passioni collettive. Cultura, politica e società (in Italian). Nuova Cultura. ISBN 978-88-6134-862-2.

- Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2.

- Ridolfi, Pierluigi (2002). Canti e poesie per un'Italia unita dal 1821 al 1861 (in Italian). Associazione Amici dell'Accademia dei Lincei.

- Ridolfi, Maurizio (2003). Almanacco della Repubblica: storia d'Italia attraverso le tradizioni, le istituzioni e le simbologie repubblicane (in Italian). Bruno Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-424-9499-7.

- Stramacci, Mauro (1991). Goffredo Mameli (in Italian). Edizioni Mediterranee. ISBN 88-272-0932-8.

- Vulpone, Pasquale (2002). Il Canto degli Italiani. Inno d'Italia (in Italian). Pellegrini. ISBN 88-8101-140-9.

External links

| Italian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Page on the official site of the Quirinale, residence of the Head of State

(in Italian with several recorded performances – click on ascolta l'Inno and choose a file to listen) - Free sheet music of Il Canto degli Italiani from Cantorion.org

- Streaming audio, lyrics and information about the Italian national anthem

- Listen to the Italian national anthem

- Fratelli d'Italia: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) (Version for chorus and piano by Claudio Dall'Albero on a musical proposal of Luciano Berio)