Kingdom of Italy (Holy Roman Empire)

The Kingdom of Italy (Latin: Regnum Italiae or Regnum Italicum, Italian: Regno d'Italia, German: Königreich Italien), also called Imperial Italy (German: Reichsitalien), was one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, along with the kingdoms of Germany, Bohemia, and Burgundy. It comprised northern and central Italy, but excluded the Republic of Venice and the Papal States. Its original capital was Pavia until the 11th century.

| Kingdom of Italy Regnum Italiae (in Latin) Regno d'Italia (in Italian) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Holy Roman Empire | |||||||||||

| 855–1801 | |||||||||||

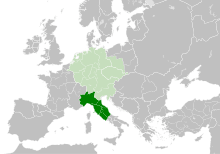

The Kingdom of Italy within the Holy Roman Empire and within Europe in the early 11th century. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Pavia (at least to 1024) | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Non-sovereign elective monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 962–973 | Otto I | ||||||||||

• 1519–1556 | Charles V1 | ||||||||||

• 1792–1801 | Francis II | ||||||||||

| Arch-Chancellor2 | |||||||||||

• 962–965 (first) | Bruno of Lotharingia | ||||||||||

• 1784–1801 (last) | Maximilian Francis of Austria | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages/Early modern period | ||||||||||

• Otto I descent in Italy | 951 | ||||||||||

| 25 December 961 855 | |||||||||||

| 1075–1122 | |||||||||||

| 1158 | |||||||||||

| 1216–1392[1] | |||||||||||

| 1494–1559 | |||||||||||

| 1792 | |||||||||||

| 9 February 1801 | |||||||||||

• Re-birth of the Kingdom of Italy (Napoleonic) | 1805 | ||||||||||

| Political subdivisions | Approx. 15 vassal entities | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Italy | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Early

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Post-Roman Kingdoms

|

||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||

|

Modern

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

In 773, Charlemagne, the King of the Franks, crossed the Alps to invade the Kingdom of the Lombards, which encompassed all of Italy except the Duchy of Rome and some Byzantine possessions in the south. In June 774, the kingdom collapsed and the Franks became masters of northern Italy. The southern areas remained under Lombard control as the Duchy of Benevento is changed into the rather independent Principality of Benevento. Charlemagne adopted the title "King of the Lombards" and in 800 was crowned "Emperor of the Romans" in Rome. Members of the Carolingian dynasty continued to rule Italy until the deposition of Charles the Fat in 887, after which they once briefly regained the throne in 894–896. Until 961, the rule of Italy was continually contested by several aristocratic families from both within and outside the kingdom.

In 961, King Otto I of Germany, already married to Adelaide, widow of a previous king of Italy, invaded the kingdom and had himself crowned in Pavia on 25 December. He continued on to Rome, where he had himself crowned emperor on 7 February 962. The union of the crowns of Italy and Germany with that of the so-called "Empire of the Romans" proved stable. Burgundy was added to this union in 1032, and by the twelfth century the term "Holy Roman Empire" had come into use to describe it. From 961 on, the Emperor of the Romans was usually also King of Italy and Germany, although emperors sometimes appointed their heirs to rule in Italy and occasionally the Italian bishops and noblemen elected a king of their own in opposition to that of Germany. The absenteeism of the Italian monarch led to the rapid disappearance of a central government in the High Middle Ages, but the idea that Italy was a kingdom within the Empire remained and emperors frequently sought to impose their will on the evolving Italian city-states. The resulting wars between Guelphs and Ghibellines, the anti-imperialist and imperialist factions, respectively, were characteristic of Italian politics in the 12th–14th centuries. The Lombard League was the most famous example of this situation; though not a declared separatist movement, it openly challenged the emperor's claim to power.

The century between the Humiliation of Canossa (1077) and the Treaty of Venice of 1177 resulted in the formation of city states independent of the Germanic Emperor. A series of wars in Lombardy from 1423 to 1454 reduced the number of competing states in Italy. The next forty years were relatively peaceful in Italy, but in 1494 the peninsula was invaded by France.

After the Imperial Reform of 1495–1512, the Italian kingdom corresponded to the unencircled territories south of the Alps. Juridically the emperor maintained an interest in them as nominal king and overlord, but the "government" of the kingdom consisted of little more than the plenipotentiaries the emperor appointed to represent him and those governors he appointed to rule his own Italian states.

The Habsburg rule in several parts of Italy continued in various forms but came to an end with the campaigns of the French Revolutionaries in 1792–1797, when a series of sister republics were set up with local support by Napoleon and then united into the Italian Republic under his Presidency. In 1805 the Republic became a new Kingdom of Italy, in personal union with France.

Lombard kingdom

After the Battle of Taginae, in which the Ostrogoth king Totila was killed, the Byzantine general Narses captured Rome and besieged Cumae. Teia, the new Ostrogothic king, gathered the remnants of the Ostrogothic army and marched to relieve the siege, but in October 552 Narses ambushed him at Mons Lactarius (modern Monti Lattari) in Campania, near Mount Vesuvius and Nuceria Alfaterna. The battle lasted two days and Teia was killed in the fighting. Ostrogothic power in Italy was eliminated, but according to Roman historian Procopius of Caesarea, Narses allowed the Ostrogothic population and their Rugian allies to live peacefully in Italy under Roman sovereignty.[3] The absence of any real authority in Italy immediately after the battle led to an invasion by the Franks and Alemanni, but they too were defeated in the battle of the Volturnus and the peninsula was, for a short time, reintegrated into the empire.[4][5]

The Kings of the Lombards (Latin: reges Langobardorum, singular rex Langobardorum) ruled that Germanic people from their invasion of Italy in 567–68 until the Lombardic identity became lost in the ninth and tenth centuries. After 568, the Lombard kings sometimes styled themselves Kings of Italy (Latin: rex totius Italiæ). Upon the Lombard defeat at the 774 Siege of Pavia, the kingdom came under the Frankish domination of Charlemagne. The Iron Crown of Lombardy (Corona Ferrea) was used for the coronation of the Lombard kings, and the kings of Italy thereafter, for centuries.[6]

The primary sources for the Lombard kings before the Frankish conquest are the anonymous 7th-century Origo Gentis Langobardorum and the 8th-century Historia Langobardorum of Paul the Deacon. The earliest kings (the pre-Lethings) listed in the Origo are almost certainly legendary. They purportedly reigned during the Migration Period; the first ruler attested independently of Lombard tradition is Tato.

The actual control of the sovereigns of both the major areas that constitute the kingdom – Langobardia Major in the centre-north (in turn divided into a western, or Neustria, and one eastern, or Austria and Tuskia) and Langobardia Minor in the centre-south, was not constant during the two centuries of life of the kingdom. An initial phase of strong autonomy of the many constituent duchies developed over time with growing regal authority, even if the dukes' desires for autonomy were never fully achieved.

The Lombard kingdom proved to be more stable than its Ostrogothic predecessor, but in 774, on the pretext of defending the Papacy, it was conquered by the Franks under Charlemagne. They kept the Italo-Lombard realm separate from their own, but the kingdom shared in all the partitions, divisions, civil wars, and succession crises of the Carolingian Empire of which it became a part until, by the end of the ninth century, the Italian kingdom was an independent, but highly decentralised, state.

Constituent of the Carolingian Empire

The death of the Emperor Lothair I in 855 led to his realm of Middle Francia being split among his three sons. The eldest, Louis II, inherited the Carolingian lands in Italy, which were now for the first time (save the brief rule of Charlemagne's son Pepin in the first decade of the century), ruled as a distinct unit. The kingdom included all of Italy as far south as Rome and Spoleto, but the rest of Italy to the south was under the rule of the Lombard Principality of Benevento or of the Byzantine Empire.

Following Louis II's death without heirs, there were several decades of confusion. The Imperial crown was initially disputed among the Carolingian rulers of West Francia (France) and East Francia (Germany), with first the western king (Charles the Bald) and then the eastern (Charles the Fat) attaining the prize. Following the deposition of the latter, local nobles – Guy III of Spoleto and Berengar of Friuli – disputed over the crown, and outside intervention did not cease, with Arnulf of Eastern Francia and Louis the Blind of Provence both claiming the Imperial throne for a time. The kingdom was also beset by Arab raiding parties from Sicily and North Africa, and central authority was minimal at best.

In the 10th century, the situation hardly improved, as various Burgundian and local noblemen continued to dispute over the crown. Order was only imposed from outside, when the German king Otto I invaded Italy and seized both the Imperial and Italian thrones for himself in 962.

Imperial Italy

In 951 King Otto I of Germany had married Adelaide of Burgundy, the widow of late King Lothair II of Italy. Otto assumed the Iron Crown of Lombardy at Pavia despite his rival Margrave Berengar of Ivrea. When in 960 Berengar attacked the Papal States, King Otto, summoned by Pope John XII, conquered the Italian kingdom and on 2 February 962 had himself crowned Holy Roman Emperor at Rome. From that time on, the Kings of Italy were always also Kings of Germany, and Italy thus became a constituent kingdom of the Holy Roman Empire, along with the Kingdom of Germany (regnum Teutonicorum) and – from 1032 – Burgundy. The German king (Rex Romanorum) would be crowned by the Archbishop of Milan with the Iron Crown in Pavia as a prelude to the visit to Rome to be crowned Emperor by the Pope.[7][8]

In general, the monarch was an absentee, spending most of his time in Germany and leaving the Kingdom of Italy with little central authority. There was also a lack of powerful landed magnates – the only notable one being the Margraviate of Tuscany, which had wide lands in Tuscany, Lombardy, and the Emilia, but which failed due to lack of heirs after the death of Matilda of Canossa in 1115. This left a power vacuum – increasingly filled by the Papacy and by the bishops, as well as by the increasingly wealthy Italian cities, which gradually came to dominate the surrounding countryside. Upon the death of Emperor Otto III in 1002, one of late Berengar's successors, Margrave Arduin of Ivrea, even succeeded in assuming the Italian crown and in defeating the Imperial forces under Duke Otto I of Carinthia. Not until 1004 could the new German King Henry II of Germany, by the aid of Bishop Leo of Vercelli, move into Italy to have himself crowned rex Italiae. Arduin ranks as the last domestic "King of Italy" before the accession of Victor Emmanuel II in 1861.

Henry's Salian successor Conrad II tried to confirm his dominion against Archbishop Aribert of Milan and other Italian aristocrats (seniores). While besieging Milan in 1037, he issued the Constitutio de feudis in order to secure the support of the vasvassores petty gentry, whose fiefs he declared hereditary. Indeed, Conrad could stable his rule, however, the Imperial supremacy in Italy remained contested.

Staufer

The cities first demonstrated their increasing power during the reign of the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1152–1190), whose attempts to restore imperial authority in the peninsula led to a series of wars with the Lombard League, a league of northern Italian cities, most of the times headed by Milan, and ultimately to a decisive victory for the League at the Battle of Legnano in 1176, that had as its leader the Milanese Guido da Landriano, which forced Frederick to made administrative, political, and judicial concessions to the municipalities, officially ending his attempt to dominate Northern Italy.[9][10]

Frederick's son Henry VI actually managed to extend Hohenstaufen authority in Italy by his conquest of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, which comprised Sicily and all of Southern Italy. Henry's son, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor – the first emperor since the 10th century to actually base himself in Italy – attempted to return to his father's task of restoring imperial authority in the northern Italian Kingdom, which led to fierce opposition not only from a reformed Lombard League, but also from the Popes, who had become increasingly jealous of their temporal realm in central Italy (theoretically a part of the Empire), and concerned about the hegemonic ambitions of the Hohenstaufen emperors.

Frederick II's efforts to bring all of Italy under his control failed as signally as those of his grandfather, and his death in 1250 marked the effective end of the Kingdom of Italy as a genuine political unit. Conflict continued between Ghibellines (Imperial supporters) and Guelfs (Papal supporters) in the Italian cities, but these conflicts bore less and less relation to the origins of the parties in question.

Decline

The Italian campaigns of the Holy Roman Emperors decreased, but the Kingdom did not become wholly meaningless. In 1310 the Luxembourg King Henry VII of Germany with 5,000 men again crossed the Alps, moved into Milan and had himself crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy, sparking a Guelph rebellion under Lord Guido della Torre. Henry restored the rule of Matteo I Visconti and proceeded to Rome, where he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by three cardinals in place of Pope Clement V in 1312. His further plans to restore the Imperial rule and to invade the Kingdom of Naples were aborted by his sudden death the next year.

Successive emperors in the 14th and 15th centuries were bound in the struggle between the rivaling Luxembourg, Habsburg and Wittelsbach dynasties. In the conflict with Frederick the Fair, King Louis IV (reigned until 1347) had himself crowned Emperor in Rome by Antipope Nicholas V in 1328. His successor Charles IV also returned to Rome to be crowned in 1355. None of the Emperors forgot their theoretical claims to dominion as Kings of Italy. Nor did the Italians themselves forget the claims of the Emperors to universal dominion: writers like Dante Alighieri (died 1321) and Marsilius of Padua (c. 1275 – c. 1342) expressed their commitment both to the principle of universal monarchy, and to the actual pretensions of Emperors Henry VII and Louis IV, respectively.

The Imperial claims to dominion in Italy mostly manifested themselves, however, in the granting of titles to the various strongmen who had begun to establish their control over the formerly republican cities. Most notably, the Emperors gave their backing to the Visconti of Milan, and King Wenceslaus created Gian Galeazzo Visconti Duke of Milan in 1395. Other families to receive new titles from the emperors were the Gonzaga of Mantua, and the Este of Ferrara and Modena.

Aftermath

By the beginning of the early modern period, the Kingdom in Italy still formally existed but had de facto splintered into completely independent and self-governing city states. Its territory had been significantly limited – the conquests of the Republic of Venice in the "domini di Terraferma" and those of the Papal States had taken most of northeastern and central Italy outside the jurisdiction of the Empire.

Nevertheless, the Emperor Charles V, owing more to his inheritance of Spain and Naples than to his position as Emperor, was able to establish his dominance in Italy to a greater extent than any Emperor since Frederick II. He drove the French from Milan, prevented an attempt by the Italian princes, with French aid, to reassert their independence in the League of Cognac. His mutinous troops sacked Rome and, coming to terms with the Medici pope Clement VII, conquered Florence where he reinstalled the Medici as Dukes of Florence after a siege. Upon the extinction of the Sforza line in Milan, Charles V claimed the territory as an imperial fief and eventually installed his son Philip as the new Duke, making the Duchy of Milan, now a possession of the Spanish Empire. This was the last usage of "Imperial" power in Italy.[11][12]

Following the reign of Charles V, no Holy Roman Emperor of the Austrian Habsburgs was crowned King of Italy. The Kingdom of Italy continued to legally exist, however, the dukes remained in full control of their duchies, holding supreme autocratic authority, and the claims to feudal overlordship had become practically meaningless.[13][14]

In the early 18th century, under the Treaty of Rastatt, to put an end to the War of the Spanish Succession, the Austrian branch of the Habsburg Monarchy received from Spain the Duchy of Milan, which they held until the Battle of Marengo, in 1800.[15][16]

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Austrians were driven from Italy by Napoleon, who set up republics throughout northern Italy, and by the Treaty of Campo Formio of 1797, Emperor Francis II relinquished any claims over the territories that made up the Kingdom of Italy. The imperial reorganization carried out in 1799–1803 left no room for Imperial claims to Italy – even the Archbishop of Cologne was gone, secularized along with the other ecclesiastical princes.[17]

In 1805, while the Holy Roman Empire was still in existence, Napoleon, by now Emperor Napoleon I, claimed the crown of the new Kingdom of Italy for himself, putting the Iron Crown on his head at Milan on 26 May 1805. The Empire itself was abolished the next year on 6 August 1806.[18][19]

See also

Notes

- Jaques, Tony. Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E.

- Lodovico Antonio Muratori; Giuseppe Oggeri Vincenti (1788). Annali d'Italia. pp. 78–81.

- De Bello Gothico IV 32, pp. 241-245

- the Deacon, Paul. History of the Lombards (The Middle Ages Series). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Deanesly, Margaret. A History of Early Medieval Europe From 476 to 911. Methuen & Co.

- Byfield, Ted. The Christians: Their First Two Thousand Years; The Quest for the City A.D. 740-1100 Pursing the Next World, They Founded This One [Vol. 6]. Christian History Project.

- Tabacco, Giovanni. The Struggle for Power in Medieval Italy: Structures of Political Rule. Cambridge University Press. p. 116.

- Orioli, R. Fra Dolcino. Nascita, vita e morte di un'eresia medievale. Jaca Book. p. 233.

- "La battaglia di Legnano". Ars Bellica. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Grillo, Paolo. Legnano 1176. Una battaglia per la libertà (in Italian). Laterza. pp. 157–160.

- Maltby, William. The Reign of Charles V (European History in Perspective). Palgrave; 2002 edition.

- "Charles V | Biography, Reign, Abdication, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- Wilson, Peter (2017-11-28). Il Sacro Romano Impero (in Italian). Il Saggiatore. ISBN 978-88-6576-606-4.

- Wilson, Peter (2017-11-28). Il Sacro Romano Impero (in Italian). Il Saggiatore. ISBN 978-88-6576-606-4.

- H. Thompson, Richard. Lothar Franz Von Schonborn and the Diplomacy of the Electorate of Mainz: From the Treaty of Ryswick to the Outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession. Springer. pp. 158–160.

- Palmer, R. R. A History of the Modern World. McGraw-Hill Education.

- "Treaty of Campo Formio | France-Austria [1797]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- David G. Chandler (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Internet Archive. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2006-12-01). "Bolstering the Prestige of the Habsburgs: The End of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806". The International History Review. 28 (4): 709–736. doi:10.1080/07075332.2006.9641109. ISSN 0707-5332.

References

- Liutprand, Antapodoseos sive rerum per Europam gestarum libri VI.

- Liutprand, Liber de rebus gestis Ottonis imperatoris.

- Anonymous, Panegyricus Berengarii imperatoris (10th century) [Mon.Germ.Hist., Script., V, p. 196].

- Anonymous, Widonis regis electio [Mon.Germ.Hist., Script., III, p. 554].

- Anonymous, Gesta Berengarii imperatoris [ed. Dumueler, Halle 1871].

.svg.png)