Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico (born Guido di Pietro; c. 1395[2] – February 18, 1455) was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, described by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists as having "a rare and perfect talent".[3] He earned his reputation primarily for with the series of frescoes he made for his own friary, San Marco, in Florence.[4]

Fra Angelico | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Guido di Pietro c. 1395 Rupecanina, Mugello, Republic of Florence |

| Died | February 18, 1455 (age about 59) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, Fresco |

Notable work | Annunciation of Cortona Fiesole Altarpiece San Marco Altarpiece Deposition of Christ Niccoline Chapel |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

| Patron(s) | Cosimo de' Medici Pope Eugene IV Pope Nicholas V |

Blessed John of Fiesole, O.P. | |

|---|---|

| Venerated in | Catholic Church (Dominican Order) |

| Beatified | October 3, 1982, Vatican City, by Pope John Paul II |

| Feast | 18 February |

He was known to contemporaries as Fra Giovanni da Fiesole (Brother John of Fiesole) and Fra Giovanni Angelico (Angelic Brother John). In modern Italian he is called Beato Angelico (Blessed Angelic One);[5] the common English name Fra Angelico means the "Angelic friar".

In 1982, Pope John Paul II proclaimed his beatification[6] in recognition of the holiness of his life, thereby making the title of "Blessed" official. Fiesole is sometimes misinterpreted as being part of his formal name, but it was merely the name of the town where he took his vows as a Dominican friar,[7] and was used by contemporaries to separate him from others who were also known as Fra Giovanni. He is listed in the Roman Martyrology[8] as Beatus Ioannes Faesulanus, cognomento Angelicus—"Blessed Giovanni of Fiesole, surnamed 'the Angelic' ".

Vasari wrote of Fra Angelico that "it is impossible to bestow too much praise on this holy father, who was so humble and modest in all that he did and said and whose pictures were painted with such facility and piety."[3]

Biography

Early life, 1395–1436

Fra Angelico was born Guido di Pietro at Rupecanina[9] in the Tuscan area of Mugello near Fiesole towards the end of the 14th century. Nothing is known of his parents. He was baptized Guido or Guidolino. The earliest recorded document concerning Fra Angelico dates from October 17, 1417 when he joined a religious confraternity or guild at the Carmine Church, still under the name of Guido di Pietro. This record reveals that he was already a painter, a fact that is subsequently confirmed by two records of payment to Guido di Pietro in January and February 1418 for work done in the church of Santo Stefano del Ponte.[10] The first record of Angelico as a friar dates from 1423, when he is first referred to as Fra Giovanni (Friar John), following the custom of those entering one of the older religious orders of taking a new name.[11] He was a member of the local community at Fiesole, not far from Florence, of the Dominican Order; one of the medieval Orders belonging to a category known as mendicant Orders because they generally lived not from the income of estates but from begging or donations. Fra, a contraction of frater (Latin for 'brother'), is a conventional title for a mendicant friar.

According to Vasari, Fra Angelico initially received training as an illuminator, possibly working with his older brother Benedetto who was also a Dominican and an illuminator. The former Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence, now a state museum, holds several manuscripts that are thought to be entirely or partly by his hand.[3] The painter Lorenzo Monaco may have contributed to his art training, and the influence of the Sienese school is discernible in his work. He also trained with master Varricho in Milan[12] He had several important charges in the convents he lived in, but this did not limit his art, which very soon became famous. According to Vasari, the first paintings of this artist were an altarpiece and a painted screen for the Charterhouse (Carthusian monastery) of Florence; none such exist there now.[3]

From 1408 to 1418, Fra Angelico was at the Dominican friary of Cortona, where he painted frescoes, now mostly destroyed, in the Dominican Church and may have been assistant to Gherardo Starnina or a follower of his.[13] Between 1418 and 1436 he was at the convent of Fiesole, where he also executed a number of frescoes for the church and the Altarpiece, which was deteriorated but has since been restored. A predella of the Altarpiece remains intact and is conserved in the National Gallery, London, and is a great example of Fra Angelico's ability. It shows Christ in Glory surrounded by more than 250 figures, including beatified Dominicans. In this period he painted some of his masterpieces including a version of The Madonna of Humility, well preserved and property of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum but on loan to the MNAC of Barcelona, an Annunciation along with a Madonna of the Pomegranate, at the Prado Museum.

San Marco, Florence, 1436–1445

.jpg)

In 1436, Fra Angelico was one of a number of the friars from Fiesole who moved to the newly built convent or friary of San Marco in Florence. This was an important move which put him in the centre of artistic activity of the region and brought about the patronage of Cosimo de' Medici, one of the wealthiest and most powerful members of the city's governing authority (or "Signoria") and founder of the dynasty that would dominate Florentine politics for much of the Renaissance. Cosimo had a cell reserved for himself at the friary in order that he might retreat from the world. It was, according to Vasari, at Cosimo's urging that Fra Angelico set about the task of decorating the convent, including the magnificent fresco of the Chapter House, the often-reproduced Annunciation at the top of the stairs leading to the cells, the Maesta (or Coronation of the Madonna) with Saints (cell 9) and the many other devotional frescoes, of smaller format but remarkable luminous quality, depicting aspects of the Life of Christ that adorn the walls of each cell.[3]

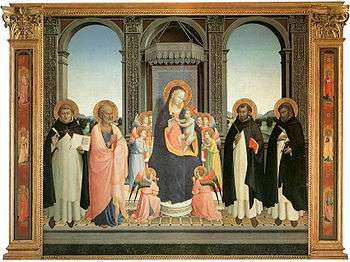

In 1439 Fra Angelico completed one of his most famous works, the San Marco Altarpiece at Florence. The result was unusual for its time. Images of the enthroned Madonna and Child surrounded by saints were common, but they usually depicted a setting that was clearly heaven-like, in which saints and angels hovered about as divine presences rather than people. But in this instance, the saints stand squarely within the space, grouped in a natural way as if they were able to converse about the shared experience of witnessing the Virgin in glory. Paintings such as this, known as Sacred Conversations, were to become the major commissions of Giovanni Bellini, Perugino and Raphael.[14]

The Vatican, 1445–1455

In 1445 Pope Eugene IV summoned him to Rome to paint the frescoes of the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament at St Peter's, later demolished by Pope Paul III. Vasari claims that at this time Fra Angelico was offered the Archbishopric of Florence by Pope Nicholas V, and that he refused it, recommending another friar for the position. The story seems possible and even likely. However, if Vasari's date is correct, then the pope must have been Eugene IV and not Nicholas, who was elected Pope only on 6 March 1447. Moreover, the archbishop in 1446–1459 was the Dominican Antoninus of Florence (Antonio Pierozzi), canonized by Pope Adrian VI in 1523. In 1447 Fra Angelico was in Orvieto with his pupil, Benozzo Gozzoli, executing works for the Cathedral. Among his other pupils were Zanobi Strozzi.[15]

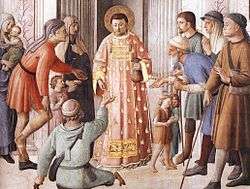

From 1447 to 1449 Fra Angelico was back at the Vatican, designing the frescoes for the Niccoline Chapel for Nicholas V. The scenes from the lives of the two martyred deacons of the Early Christian Church, St. Stephen and St. Lawrence may have been executed wholly or in part by assistants. The small chapel, with its brightly frescoed walls and gold leaf decorations gives the impression of a jewel box. From 1449 until 1452, Fra Angelico returned to his old convent of Fiesole, where he was the Prior.[3][16]

Death and beatification

In 1455, Fra Angelico died while staying at a Dominican convent in Rome, perhaps on an order to work on Pope Nicholas' chapel. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[3][16][17]

When singing my praise, don't liken my talents to those of Apelles.

Say, rather, that, in the name of Christ, I gave all I had to the poor.The deeds that count on Earth are not the ones that count in Heaven.

I, Giovanni, am the flower of Tuscany.

— Translation of epitaph[3]

The English writer and critic William Michael Rossetti wrote of the friar:

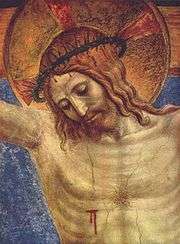

From various accounts of Fra Angelico’s life, it is possible to gain some sense of why he was deserving of canonization. He led the devout and ascetic life of a Dominican friar, and never rose above that rank; he followed the dictates of the order in caring for the poor; he was always good-humored. All of his many paintings were of divine subjects, and it seems that he never altered or retouched them, perhaps from a religious conviction that, because his paintings were divinely inspired, they should retain their original form. He was wont to say that he who illustrates the acts of Christ should be with Christ. It is averred that he never handled a brush without fervent prayer and he wept when he painted a Crucifixion. The Last Judgment and the Annunciation were two of the subjects he most frequently treated.[18][16]

Pope John Paul II beatified Fra Angelico on October 3, 1982, and in 1984 declared him patron of Catholic artists.[6]

Angelico was reported to say "He who does Christ's work must stay with Christ always". This motto earned him the epithet "Blessed Angelico", because of the perfect integrity of his life and the almost divine beauty of the images he painted, to a superlative extent those of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Evaluation

Background

Fra Angelico was working at a time when the style of painting was in a state of change. This process of change had begun a hundred years previous with the works of Giotto and several of his contemporaries, notably Giusto de' Menabuoi, both of whom had created their major works in Padua, although Giotto was trained in Florence by the great Gothic artist, Cimabue, and painted a fresco cycle of St Francis in the Bardi Chapel in the Basilica di Santa Croce. Giotto had many enthusiastic followers, who imitated his style in fresco, some of them, notably the Lorenzetti, achieving great success.[14]

Patronage

The patrons of these artists were most often monastic establishments or wealthy families endowing a church. Because the paintings often had devotional purpose, the clients tended to be conservative. Frequently, it would seem, the wealthier the client, the more conservative the painting. There was a very good reason for this. The paintings that were commissioned made a statement about the patron. Thus the more gold leaf it displayed, the more it spoke to the patron's glory. The other valuable commodities in the paint-box were lapis lazuli and vermilion. Paint made from these colours did not lend itself to a tonal treatment. The azure blue made of powdered lapis lazuli went on flat, the depth and brilliance of colour being, like the gold leaf, a sign of the patron's ability to provide well. For these reasons, altarpieces are often much more conservatively painted than frescoes, which were often of almost life-sized figures and relied upon a stage-set quality rather than lavish display in order to achieve effect.[19]

Contemporaries

Fra Angelico was the contemporary of Gentile da Fabriano. Gentile's altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi, 1423, in the Uffizi is regarded as one of the greatest works of the style known as International Gothic. At the time it was painted, another young artist, known as Masaccio, was working on the frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel at the church of the Carmine. Masaccio had fully grasped the implications of the art of Giotto. Few painters in Florence saw his sturdy, lifelike and emotional figures and were not affected by them. His work partner was an older painter, Masolino, of the same generation as Fra Angelico. Masaccio died at 27, leaving the work unfinished.[14]

Altarpieces

The works of Fra Angelico reveal elements that are both conservatively Gothic and progressively Renaissance. In the altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, are all the elements that a very expensive altarpiece of the 14th century was expected to provide; a precisely tooled gold background, much azure, much vermilion and an obvious display of arsenic green. The workmanship of the gilded haloes and gold-edged robes is exquisite and all very Gothic. What makes this a Renaissance painting, as against Gentile da Fabriano's masterpiece, is the solidity, the three-dimensionality and naturalism of the figures and the realistic way in which their garments hang or drape around them. Even though it is clouds these figures stand upon, and not the earth, they do so with weight.[14]

Frescoes

The series of frescoes that Fra Angelico painted for the Dominican friars at San Marcos realise the advancements made by Masaccio and carry them further. Away from the constraints of wealthy clients and the limitations of panel painting, Fra Angelico was able to express his deep reverence for his God and his knowledge and love of humanity. The meditational frescoes in the cells of the convent have a quieting quality about them. They are humble works in simple colours. There is more mauvish-pink than there is red, and the brilliant and expensive blue is almost totally lacking. In its place is dull green and the black and white of Dominican robes. There is nothing lavish, nothing to distract from the spiritual experiences of the humble people who are depicted within the frescoes. Each one has the effect of bringing an incident of the life of Christ into the presence of the viewer. They are like windows into a parallel world. These frescoes remain a powerful witness to the piety of the man who created them.[14] Vasari relates that Cosimo de' Medici seeing these works, inspired Fra Angelico to create a large Crucifixion scene with many saints for the Chapter House. As with the other frescoes, the wealthy patronage did not influence the Friar's artistic expression with displays of wealth.[3]

Masaccio ventured into perspective with his creation of a realistically painted niche at Santa Maria Novella. Subsequently, Fra Angelico demonstrated an understanding of linear perspective particularly in his Annunciation paintings set inside the sort of arcades that Michelozzo and Brunelleschi created at San’ Marco's and the square in front of it.[14]

Lives of the Saints

When Fra Angelico and his assistants went to the Vatican to decorate the chapel of Pope Nicholas, the artist was again confronted with the need to please the very wealthiest of clients. In consequence, walking into the small chapel is like stepping into a jewel box. The walls are decked with the brilliance of colour and gold that one sees in the most lavish creations of the Gothic painter Simone Martini at the Lower Church of St Francis of Assisi, a hundred years earlier. Yet Fra Angelico has succeeded in creating designs which continue to reveal his own preoccupation with humanity, with humility and with piety. The figures, in their lavish gilded robes, have the sweetness and gentleness for which his works are famous. According to Vasari:

In their bearing and expression, the saints painted by Fra Angelico come nearer to the truth than the figures done by any other artist.[3]

It is probable that much of the actual painting was done by his assistants to his design. Both Benozzo Gozzoli and Gentile da Fabriano were highly accomplished painters. Benozzo took his art further towards the fully developed Renaissance style with his expressive and lifelike portraits in his masterpiece depicting the Journey of the Magi, painted in the Medici's private chapel at their palazzo.[20]

%3B_Fra_Angelico1.jpg)

Artistic legacy

Through Fra Angelico's pupil Benozzo Gozzoli's careful portraiture and technical expertise in the art of fresco we see a link to Domenico Ghirlandaio, who in turn painted extensive schemes for the wealthy patrons of Florence, and through Ghirlandaio to his pupil Michelangelo and the High Renaissance.

Apart from the lineal connection, superficially there may seem little to link the humble priest with his sweetly pretty Madonnas and timeless Crucifixions to the dynamic expressions of Michelangelo's larger-than-life creations. But both these artists received their most important commissions from the wealthiest and most powerful of all patrons, the Vatican.

When Michelangelo took up the Sistine Chapel commission, he was working within a space that had already been extensively decorated by other artists. Around the walls the Life of Christ and Life of Moses were depicted by a range of artists including his teacher Ghirlandaio, Raphael's teacher Perugino and Botticelli. They were works of large scale and exactly the sort of lavish treatment to be expected in a Vatican commission, vying with each other in complexity of design, number of figures, elaboration of detail and skillful use of gold leaf. Above these works stood a row of painted Popes in brilliant brocades and gold tiaras. None of these splendours have any place in the work which Michelangelo created. Michelangelo, when asked by Pope Julius II to ornament the robes of the Apostles in the usual way, responded that they were very poor men.[14]

Within the cells of San’Marco, Fra Angelico had demonstrated that painterly skill and the artist's personal interpretation were sufficient to create memorable works of art, without the expensive trappings of blue and gold. In the use of the unadorned fresco technique, the clear bright pastel colours, the careful arrangement of a few significant figures and the skillful use of expression, motion and gesture, Michelangelo showed himself to be the artistic descendant of Fra Angelico. Frederick Hartt describes Fra Angelico as "prophetic of the mysticism" of painters such as Rembrandt, El Greco and Zurbarán.[14]

Works

Early works, 1408–1436

Rome

- Panel, The Crucifixion (c. 1420-1423), possibly Fra Angelico's only signed work. Now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.[21]

- Annunciation (c. 1430) – Diocesan Museum, Cortona

- Altarpiece - Coronation of the Virgin, with predellas of Miracles of St Dominic, Louvre, Paris

- Virgin and Child between Saints Thomas Aquinas, Barnabas, Dominic and Peter Martyr (1424) - Church of San Domenico, Fiesole

- Predella - Christ in Majesty, National Gallery, London.

Florence, Santa Trinita

- Deposition of Christ, said by Vasari to have been "painted by a saint or an angel". Now in the National Museum of San Marco, Florence.

- Coronation of the Virgin (c. 1432), Uffizi, Florence

- Coronation of the Virgin (c. 1434-1435), Louvre, Paris

Florence, Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Last Judgement, Accademia, Florence

Florence, Santa Maria Novella

- Altarpiece - Coronation of the Virgin, Uffizi.

San Marco, Florence, 1436–1445

- Altarpiece for chancel – Virgin with Saints Cosmas and Damian, attended by Saints Dominic, Peter, Francis, Mark, John Evangelist and Stephen. Cosmas and Damian were patrons of the Medici. The altarpiece was commissioned in 1438 by Cosimo de' Medici. It was removed and disassembled during the renovation of the convent church in the seventeenth century. Two of the nine predella panels remain at the convent; seven are in Washington, Munich, Dublin and Paris. Unexpectedly, in 2006 the last two missing panels, Dominican saints from the side panels, turned up in the estate of a modest collector in Oxfordshire, who had bought them in California in the 1960s.[22]

- Altarpiece ? – Madonna and Child with twelve Angels (life sized); Uffizi.

- Altarpiece – The Annunciation

- San Marco Altarpiece

- Two versions of the Crucifixion with St Dominic; in the Cloister

- Very large Crucifixion with Virgin and 20 saints; in the Chapter House

- The Annunciation; at the top of the Dormitory stairs. This is probably the most reproduced of all Fra Angelico's paintings.

- Virgin enthroned with Four Saints; in the Dormitory passage

Each cell is decorated with a fresco which matches in size and shape the single round-headed window beside it. The frescoes are apparently for contemplative purpose. They have a pale, serene, unearthly beauty. Many of Fra Angelico's finest and most reproduced works are among them. There are, particularly in the inner row of cells, some of less inspiring quality and of more repetitive subject, perhaps completed by assistants.[14] Many pictures include Dominican saints as witnesses of scene each in one of the nine traditional prayer postures depicted in De Modo Orandi. The friar using the cell could place himself in the scene.

- The Adoration of the Magi

- The Transfiguration

- Noli me Tangere

- The three Marys at the tomb.

- The Road to Emmaus, with two Dominicans as the disciples

- There are many versions of the Crucifixion

- The Mocking of Christ

Late works, 1445–1455

Orvieto Cathedral

Three segments of the ceiling in the Cappella Nuova, with the assistance of Benozzo Gozzoli.

- Christ in Glory

- The Virgin Mary

- The Apostles

The Chapel of Pope Nicholas V, at the Vatican, was probably painted with much assistance from Benozzo Gozzoli and Gentile da Fabriano. The entire surface of wall and ceiling is sumptuously painted. There is much gold leaf for borders and decoration, and a great use of brilliant blue made from lapis lazuli.

- The life of St Stephen

- The life of St Lawrence

- The Four Evangelists.

Discovery of lost works

Worldwide press coverage reported in November 2006 that two missing masterpieces by Fra Angelico had turned up, having hung in the spare room of the late Jean Preston, in her terrace house in Oxford, England. Her father had bought them for £100 each in the 1960s then bequeathed them to her when he died.[23] Preston, an expert medievalist, recognised them as being high quality Florentine renaissance, but did not realize that they were works by Fra Angelico until they were identified in 2005 by Michael Liversidge of Bristol University.[24] There was almost no demand at all for medieval art during the 1960s and no dealers showed any interest, so Preston's father bought them almost as an afterthought along with some manuscripts. Coincidentally the manuscripts turned out to be high quality Victorian forgeries by The Spanish Forger. The paintings are two of eight side panels of a large altarpiece painted in 1439 for Fra Angelico's monastery at San Marco, which was later split up by Napoleon's army. While the centre section is still at the monastery, the other six small panels are in German and US museums. These two panels were presumed lost forever. The Italian Government had hoped to purchase them but they were outbid at auction on 20 April 2007 by a private collector for £1.7M.[23] Both panels are now restored and exhibited in the San Marco Museum in Florence.

See also

- Lists of painters

- List of Italian painters

- List of famous Italians

- Early Renaissance painting

- Poor Man's Bible

- Fray Angelico Chavez Franciscan Friar, historian and artist who was named after Fra Angelico due to his interest in painting.

- Western painting

- Fra Angelico catalog raisonné, 1970

Footnotes

- Considered to be a posthumous portrait of Fra Angelico.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists. Penguin Classics, 1965.

- Norwich, John Julius (1990). Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Arts. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 16. ISBN 978-0198691372.

- Andrea del Sarto, Raphael and Michelangelo were all called "Beato" by their contemporaries because their skills were seen as a special gift from God

- Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret (1999). John Paul II's Book of Saints. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 156. ISBN 0-87973-934-7.

- Rossetti 1911, p. 6.

- Roman Martyrology—the official publication which includes all Saints and Blesseds recognised by the Roman Catholic Church

- "Comune di Vicchio (Firenze), La terra natale di Giotto e del Beato Angelico". zoomedia. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Werner Cohn, Il Beato Angelico e Battista di Biagio Sanguigni. Revista d’Arte, V, (1955): 207–221.

- Stefano Orlandi, Beato Angelico; Monographia Storica della Vita e delle Opere con Un’Appendice di Nuovi Documenti Inediti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1964.

- Rossetti 1911, pp. 6-7.

- "Gherardo Starnina". Artists. Getty Center. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-28.Getty Education[]

- Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970) Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-23136-2

- "Strozzi, Zanobi". The National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Rossetti, William Michael (as attributed). "Fra Angelico". orderofpreachersindependent.org. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- The tomb has been given greater visibility since the beatification.

- Rossetti 1911, p. 7.

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy,(1974) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-881329-5

- Paolo Morachiello, Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

- Finocchio, Author: Ross. "Fra Angelico (Guido di Pietro) (ca. 1395–1455) | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- "San Marco Altarpiece". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- Morris, Steven (20 April 2007). "Lost altar masterpieces found in spare bedroom fetch £1.7m". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- Morris, Steven (14 November 2006). "A £1m art find behind the spare room door". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

References

- Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780300057348

- Morachiello, Paolo. Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

- Frederick Hartt. A History of Italian Renaissance Art, Thames & Hudson, 1970. ISBN 0-500-23136-2

- Giorgio Vasari. Lives of the Artists. first published 1568. Penguin Classics, 1965.

- Donald Attwater. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin Reference Books, 1965.

- Luciano Berti. Florence, the city and its Art. Bercocci, 1979.

- Werner Cohn. Il Beato Angelico e Battista di Biagio Sanguigni. Revista d’Arte, V, (1955): 207–221.

- Stefano Orlandi. Beato Angelico; Monographia Storica della Vita e delle Opere con Un’Appendice di Nuovi Documenti Inediti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1964.

Further reading

- Fra Angelico: Heaven of Earth, ed. by Nathaniel Silver, Boston : Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2018

- Gerardo de Simone, Il Beato Angelico a Roma. Rinascita delle arti e Umanesimo cristiano nell'Urbe di Niccolò V e Leon Battista Alberti, Firenze, Olschki, 2017 (Fondazione Carlo Marchi, Studi, vol. 34)

- Cyril Gerbron, Fra Angelico. Liturgie et mémoire (= Études Renaissantes, 18), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2016. ISBN 978-2-503-56769-3;

- Gerardo de Simone, La bottega di un frate pittore: il Beato Angelico tra Fiesole, FIrenze e Roma, in " Revista Diálogos Mediterrânicos" (Curitiba, Brasil), n. 8, 2015, ISSN 2237-6585, pp. 48-85 – http://www.dialogosmediterranicos.com.br/index.php/RevistaDM

- Gerardo de Simone, Fra Angelico : perspectives de recherche, passées et futures, in "Perspective, la revue de l'INHA. Actualités de la recherche en histoire de l’art", 2013 - I, pp. 25-42

- Gerardo de Simone, Velut alter Iottus. Il Beato Angelico e i suoi “profeti trecenteschi”, in “1492. Rivista della Fondazione Piero della Francesca”, 2, 2009 (2010), pp. 41-66

- Gerardo de Simone, L’Angelico di Pisa. Ricerche e ipotesi intorno al Redentore benedicente del Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, in “Polittico”, Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press, 5, 2008, pp. 5-35

- Gerardo de Simone, L’ultimo Angelico. Le “Meditationes” del cardinal Torquemada e il ciclo perduto nel chiostro di S. Maria sopra Minerva, in: “Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte” (Carocci Editore, Roma), 76, 2002, pp. 41-87

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration. University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-14813-0 Discussion of how Fra Angelico challenged Renaissance naturalism and developed a technique to portray "unfigurable" theological ideas.

- Gilbert, Creighton, How Fra Angelico and Signorelli Saw the End of the World, Penn State Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02140-3

- Spike, John T. Angelico, New York, 1997.

- Supino, J. B., Fra Angelico, Alinari Brothers, Florence, undated, from Project Gutenberg

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Fra Angelico. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fra Angelico. |

- Fra Angelico – Painter of the Early Renaissance

- Fra Angelico in the "History of Art"

- Ross Finocchio, Robert Lehman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Fra Angelico Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (October 26, 2005 – January 29, 2006).

- "Soul Eyes" Review of the Fra Angelico show at the Met, by Arthur C. Danto in The Nation, (January 19, 2006).

- Fra Angelico, Catherine Mary Phillimore, (Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1892)

- Frescoes and paintings gallery

- Italian Paintings: Florentine School, a collection catalog containing information about the artist and his works (see pages: 77-82).

- Carl Brandon Strehlke, "Saint Francis of Assisi by Fra Angelico (cat. 14), in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.