The Betrothed (Manzoni novel)

The Betrothed (Italian: I promessi sposi [i proˈmessi ˈspɔːzi]) is an Italian historical novel by Alessandro Manzoni, first published in 1827, in three volumes, and significantly revised and rewritten until the definitive version published between 1840 and 1842. It has been called the most famous and widely read novel in the Italian language.[1]

Frontispiece of 1842 edition | |

| Author | Alessandro Manzoni |

|---|---|

| Original title | I promessi sposi |

| Translator | Charles Swan |

| Country | Lombardy, Austrian Empire |

| Language | Italian |

| Genre | Historical novel |

Publication date | 1827 (first version) 1842 (revised version) (Title pages give wrong dates because of delays in publication) |

Published in English | 1828 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 720 |

Set in northern Italy in 1628, during the oppressive years of direct Spanish rule. It is also noted for the extraordinary description of the plague that struck Milan around 1630.

The novel deals with a variety of themes, from the illusory nature of political power to the inherent injustice of any legal system; from the cowardly, hypocritical nature of one prelate (the parish priest don Abbondio) and the heroic sainthood of other priests (the friar Padre Cristoforo, the cardinal Federico Borromeo), to the unwavering strength of love (the relationship between Renzo and Lucia, and their struggle to finally meet again and be married). The novel is renowned for offering keen insights into the meanderings of the human mind.

I promessi sposi was made into an opera of the same name by Amilcare Ponchielli[2] in 1856 and by Errico Petrella[3] in 1869. There have been many film versions of I promessi sposi, including I promessi sposi (1908),[4] The Betrothed (1941)[5] The Betrothed (1990),[6] and Renzo and Lucia, made for television in 2004.[7]

In May 2015, at a weekly general audience at St. Peter's Square, Pope Francis asked engaged couples to read the novel for edification before marriage.[8]

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

Writing and publication

Manzoni hatched the basis for his novel in 1821 when he read a 1627 Italian edict that specified penalties for any priest who refused to perform a marriage when requested to do so.[9] More material for his story came from Giuseppe Ripamonti's Milanese Chronicles.[1]

The first version, Fermo e Lucia, was written between April 1821 and September 1823.[10] He then heavily revised it, finishing in August 1825; it was published on 15 June 1827, after two years of corrections and proof-checking. Manzoni's chosen title, Gli sposi promessi, was changed for the sake of euphony shortly before its final commitment to printing.

In the early 19th century, there was still controversy as to what form the standard literary language of Italy should take. Manzoni was firmly in favour of the dialect of Florence and, as he himself put it, after "washing his clothes [vocabulary] on the banks of the Arno [the river passing through Florence]", he revised the novel's language for its republication in 1842, cleansing it of many Lombard regionalisms.

Plot summary

Chapters 1–8: Flight from the village

Renzo and Lucia, a couple living in a village in Lombardy, near Lecco, on Lake Como, are planning to wed on 8 November 1628. The parish priest, don Abbondio, is walking home on the eve of the wedding when he is accosted by two "bravi" (thugs) who warn him not to perform the marriage, because the local baron (Don Rodrigo) has forbidden it.

When he presents himself for the wedding ceremony, Renzo is amazed to hear that the marriage is to be postponed (the priest didn't have the courage to tell the truth). An argument ensues and Renzo succeeds in extracting from the priest the name of Don Rodrigo. It turns out that Don Rodrigo has his eye on Lucia and that he had a bet about her with his cousin Count Attilio.

Lucia's mother, Agnese, advises Renzo to ask the advice of "Dr. Azzeccagarbugli" (Dr. Quibbleweaver, in Colquhoun's translation), a lawyer in the town of Lecco. Dr. Azzeccagarbugli is at first sympathetic: thinking Renzo is actually the perpetrator, he shows Renzo a recent edict criminalising the making of threats to procure or prevent marriages, but when he hears the name of Don Rodrigo, he panics and drives Renzo away. Lucia sends a message to "Fra Cristoforo" (Friar Christopher), a respected Capuchin friar at the monastery of Pescarenico, asking him to come as soon as he can.

When Fra Cristoforo comes to Lucia's cottage and hears the story, he immediately goes to Don Rodrigo's mansion, where he finds the baron at a meal with his cousin Count Attilio, along with four guests, including the mayor and Dr. Azzeccagarbugli. When Don Rodrigo is taken aside by the friar, he explodes with anger at his presumption and sends him away, but not before an old servant has a chance to offer his help to Cristoforo.

Meanwhile, Agnese has come up with a plan. In those days, it was possible for two people to marry by declaring themselves married before a priest and in the presence of two amenable witnesses. Renzo runs to his friend Tonio and offers him 25 lire if he agrees to help. When Fra Cristoforo returns with the bad news, they decide to put their plan into action.

The next morning, Lucia and Agnese are visited by beggars, Don Rodrigo's men in disguise. They examine the house in order to plan an assault. Late at night, Agnese distracts Don Abbondio's servant Perpetua while Tonio and his brother Gervaso enter Don Abbondio's study, ostensibly to pay a debt. They are followed indoors secretly by Lucia and Renzo. When they try to carry out their plan, the priest throws the tablecloth in Lucia's face and drops the lamp. They struggle in the darkness.

In the meantime, Don Rodrigo's men invade Lucia's house, but nobody is there. A boy named Menico arrives with a message of warning from Fra Cristoforo and they seize him. When they hear the alarm being raised by the sacristan, who is calling for help on the part of Don Abbondio who raised the alarm of invaders in his home, they assume they have been betrayed and flee in confusion. Menico sees Agnese, Lucia and Renzo in the street and warns them not to return home. They go to the monastery, where Fra Cristoforo gives Renzo a letter of introduction to a certain friar at Milan, and another letter to the two women, to organize a refuge at a convent in the nearby city of Monza.

Chapters 9–10: The Nun of Monza

Lucia is entrusted to the nun Gertrude, a strange and unpredictable noblewoman whose story is told in these chapters.

A child of the most important family of the area, her father decided to send her to the cloisters for no other reason than to simplify his affairs: he wished to keep his properties united for his first-born, heir to the family's title and riches. As she grew up, she sensed that she was being forced by her parents into a life which would comport but little with her personality. However, fear of scandal, as well as manoeuvres and menaces from her father, induced Gertrude to lie to her interviewers in order to enter the convent of Monza, where she was received as la Signora ("the lady", also known as The Nun of Monza). Later, she fell under the spell of a young man of no scruples, Egidio, associated with the worst baron of that time, the Innominato (the "Unnamed"). Egidio and Gertrude became lovers and when another nun discovered their relationship they killed her.

Chapters 11–17: Renzo in Milan

Renzo arrives in famine-stricken Milan and goes to the monastery, but the friar he is seeking is absent and so he wanders further into the city. A bakery in the Corsia de' Servi, El prestin di scansc ("Bakery of the Crutches"), is destroyed by a mob, who then go to the house of the Commissioner of Supply in order to lynch him. He is saved in the nick of time by Ferrer, the Grand Chancellor, who arrives in a coach and announces he is taking the Commissioner to prison. Renzo becomes prominent as he helps Ferrer make his way through the crowd.

After witnessing these scenes, Renzo joins in a lively discussion and reveals views which attract the notice of a police agent in search of a scapegoat. The agent tries to lead Renzo directly to "the best inn" (i.e. prison) but Renzo is tired and stops at one nearby where, after being plied with drink, he reveals his full name and address. The next morning, he is awakened by a notary and two bailiffs, who handcuff him and start to take him away. In the street Renzo announces loudly that he is being punished for his heroism the day before and, with the aid of sympathetic onlookers, he effects his escape. Leaving the city by the same gate through which he entered, he sets off for Bergamo, knowing that his cousin Bortolo lives in a village nearby. Once there, he will be beyond the reach of the authorities of Milan (under Spanish domination), as Bergamo is territory of the Most Serene Republic of Venice.

At an inn in Gorgonzola, he overhears a conversation which makes it clear to him how much trouble he is in and so he walks all night until he reaches the River Adda. After a short sleep in a hut, he crosses the river at dawn in the boat of a fisherman and makes his way to his cousin's house, where he is welcomed as a silk-weaver under the pseudonym of Antonio Rivolta. The same day, orders for Renzo's arrest reach the town of Lecco, to the delight of Don Rodrigo.

Chapters 18–24: Lucia and the Unnamed

News of Renzo's disgrace comes to the convent, but later Lucia is informed that Renzo is safe with his cousin. Their reassurance is short-lived: when they receive no word from Fra Cristoforo for a long time, Agnese travels to Pescarenico, where she learns that he has been ordered by a superior to the town of Rimini. In fact, this has been engineered by Don Rodrigo and Count Attilio, who have leaned on a mutual uncle of the Secret Council, who has leaned on the Father Provincial. Meanwhile, Don Rodrigo has organised a plot to kidnap Lucia from the convent. This involves a great robber baron whose name has not been recorded, and who hence is called l'Innominato, the Unnamed.

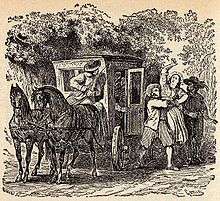

Gertrude, blackmailed by Egidio, a neighbor (acquaintance of l'Innominato and Gertrude's lover), persuades Lucia to run an errand which will take her outside the convent for a short while. In the street Lucia is seized and bundled into a coach. After a nightmarish journey, Lucia arrives at the castle of the Unnamed, where she is locked in a chamber.

The Unnamed is troubled by the sight of her, and spends a horrible night in which memories of his past and the uncertainty of his future almost drive him to suicide. Meanwhile, Lucia spends a similarly restless night, during which she vows to renounce Renzo and maintain perpetual virginity if she is delivered from her predicament. Towards the morning, on looking out of his window, the Unnamed sees throngs of people walking past. They are going to listen to the famous Archbishop of Milan, Cardinal Federigo Borromeo. On impulse, the Unnamed leaves his castle in order to meet this man. This meeting prompts a miraculous conversion which marks the turning-point of the novel. The Unnamed announces to his men that his reign of terror is over. He decides to take Lucia back to her native land under his own protection, and with the help of the archbishop the deed is done.

Chapters 25–27: Fall of Don Rodrigo

The astonishing course of events leads to an atmosphere in which Don Rodrigo can be defied openly and his fortunes take a turn for the worse. Don Abbondio is reprimanded by the archbishop.

Lucia, miserable about her vow to renounce Renzo, still frets about him. He is now the subject of diplomatic conflict between Milan and Bergamo. Her life is not improved when a wealthy busybody, Donna Prassede, insists on taking her into her household and admonishing her for getting mixed up with a good-for-nothing like Renzo.

Chapters 28–30: Famine and war

The government of Milan is unable to keep bread prices down by decree and the city is swamped by beggars. The lazzaretto is filled with the hungry and sick.

Meanwhile, the Thirty Years' War brings more calamities. The last three dukes of the house of Gonzaga die without legitimate heirs sparking a war for control of northern Italy, with France and the Holy Roman Empire backing rival claimants. In September 1629, German armies under Count Rambaldo di Collalto descend on Italy, looting and destroying. Agnese, Don Abbondio and Perpetua take refuge in the well-defended territory of the Unnamed. In their absence, their village is wrecked by the mercenaries.

Chapters 31–33: Plague

These chapters are occupied with an account of the plague of 1630, largely based on Giuseppe Ripamonti's De peste quae fuit anno 1630 (published in 1640). Manzoni's full version of this, Storia della Colonna Infame, was finished in 1829, but was not published until it was included as an appendix to the revised edition of 1842.

The end of August 1630 sees the death in Milan of the original villains of the story. Renzo, troubled by Agnese's letters and recovering from plague, returns to his native village to find that many of the inhabitants are dead and that his house and vineyard have been destroyed. The warrant, and Don Rodrigo, are forgotten. Tonio tells him that Lucia is in Milan.

Chapters 34–38: Conclusion

On his arrival in Milan, Renzo is astonished at the state of the city. His highland clothes invite suspicion that he is an "anointer"; that is, a foreign agent deliberately spreading plague in some way. He learns that Lucia is now languishing at the Lazzaretto of Milan, along with 16,000 other victims of the plague.

But in fact, Lucia is already recuperating. Renzo and Lucia are reunited by Fra Cristoforo, but only after Renzo first visits and forgives the dying Don Rodrigo. The friar absolves her of her vow of celibacy. Renzo walks through a rainstorm to see Agnese at the village of Pasturo. When they all return to their native village, Lucia and Renzo are finally married by Don Abbondio and the couple make a fresh start at a silk-mill at the gates of Bergamo.

Characters

- Lorenzo Tramaglino, or in short form Renzo, is a young silk-weaver of humble origins, engaged to Lucia, whom he loves deeply. Initially rather naïve, he becomes more worldly wise during the story as he is confronted with many difficulties: he is separated from Lucia and then unjustly accused of being a criminal. Renzo is somewhat hot-tempered, but also gentle and honest.

- Lucia Mondella is a kind young woman who loves Renzo; she is pious and devoted, but also very shy and demure. She is forced to flee from her village to escape from Don Rodrigo in one of the most famous scenes of Italian literature, the Addio ai Monti or "Farewell to the mountains".

- Don Abbondio is the priest who refuses to marry Renzo and Lucia because he has been threatened by Don Rodrigo's men; he meets the two protagonists several times during the novel. The cowardly, morally mediocre Don Abbondio provides most of the book's comic relief; however, he is not merely a stock character, as his moral failings are portrayed by Manzoni with a mixture of irony, sadness and pity, as has been noted by Luigi Pirandello in his essay "On Humour" (Saggio sull'Umorismo).

- Fra Cristoforo is a brave and generous friar who helps Renzo and Lucia, acting as a sort of "father figure" to both and as the moral compass of the novel. Fra Cristoforo was the son of a wealthy family, and joined the Capuchin Order after killing a man.

- Don Rodrigo is a cruel and despicable Spanish nobleman and the novel's main villain. As overbearing local baron, he decides to forcibly prevent the marriage of Renzo and Lucia, threatens to kill Don Abbondio if he marries the two and tries to kidnap Lucia. He is a clear reference to the foreign domination and oppression in Lombardy, first dominated by Spain and later by the Austrian Empire.

- L'Innominato (literally: the Unnamed) is probably the novel's most complex character, a powerful and feared criminal of very high family who is torn between his ferocious past and the increasing disgust that he feels for his life. Based on the historical character of Francesco Bernardino Visconti,[11] who was really converted by a visit of Federigo Borromeo.

- Agnese Mondella is Lucia's mother: goodhearted and sagacious but often indiscreet.

- Federico Borromeo (Federigo in the book) is a virtuous and zealous cardinal; an actual historical character, younger cousin of Saint Charles.

- Perpetua is Don Abbondio's loquacious servant.

- La monaca di Monza (The Nun of Monza) is a tragic figure, a bitter, frustrated, sexually deprived and ambiguous woman. She befriends Lucia and becomes genuinely fond of her, but her dark past haunts her. This character is based on an actual woman, Marianna de Leyva.

- Griso is one of Don Rodrigo's henchmen, a silent and treacherous man.

- Dr. Azzeccagarbugli ("Quibbleweaver") is a corrupt lawyer.

- Count Attilio is Don Rodrigo's malevolent cousin.

- Nibbio (Kite - the bird) is the Innominato's right-hand man, who precedes and then happily follows his master's way of redemption.

- Don Ferrante is a phony intellectual and erudite scholar who believes the plague is caused by astrological forces.

- Donna Prassede is Don Ferrante's wife, who is willing to help Lucia but is also an opinionated busybody.

Significance

The novel is commonly described as "the most widely read work in the Italian language."[12] It became a model for subsequent Italian literary fiction.[12] Scholar Sergio Pacifici states that no other Italian literary work, with the exception of the Divine Comedy, "has been the object of more intense scrutiny or more intense scholarship."[12]

Many Italians believe that the novel is not fully appreciated abroad.[12] In Italy the novel is considered a true masterpiece of world literature and a basis for the modern Italian language,[13] and as such is widely studied in Italian secondary schools (usually in the second year, when students are 15). Many expressions, quotes and names from the novel are still commonly used in Italian, such as Perpetua (meaning a priest's house worker) or Questo matrimonio non s'ha da fare ("This marriage is not to be performed", used ironically).

The novel is not only about love and power: the great questions about evil, about innocents suffering, are the underlying theme of the book. The chapters 31-34, about the famine and the plague, are a powerful picture of material and moral devastation. Manzoni does not offer simple answers but leaves those questions open for the reader to meditate on.[14] The main idea, proposed throughout the novel, is that, against the many injustices that they suffer in their life, the poor can only hope, at best, in a small anticipation of the divine justice, which can be expected in its entirety only in the afterlife: therefore life should be lived with faith and endurance, in the expectation of a reward in the afterlife.

The Betrothed has similarities with Walter Scott's historic novel Ivanhoe, although evidently distinct.[15]

English translations

- The Betrothed Lovers (1828, abridged), by the Rev. Charles Swan, published at Pisa.[16]

- Three new translations (1834), one of them printed in New York under the title Lucia, The Betrothed.

- Two new translations (1844, 1845); the 1844 translation was the one most reprinted in the 19th century

- The Betrothed (1924), by Daniel J. Connor

- The Betrothed (1951, with later revisions), by Archibald Colquhoun, ISBN 978-0-375-71234-0[16]

- The Betrothed (1972), by Bruce Penman, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-044274-X

- Promise of Fidelity (2002, abridged), by Omero Sabatini, ISBN 0-7596-5344-5

Reviewing previous translations in 1972, Bruce Penham found that the vast majority of English translations used the first unrevised and inferior 1827 edition of the novel in Italian and often cut material unannounced.[17]

Film adaptations

The novel has been adapted into films on several occasions including:

- The Betrothed (1923)

- The Betrothed (1941)

- The Betrothed (1964)

- I Promessi Sposi, Italian fiction produced by RAI in 1967, directed by Sandro Bolchi, screenplayed with Riccardo Bacchelli.

- I Promessi Sposi, Italian fiction parody produced by RAI in 1990, directed and interpreted by Il Trio (formed by Anna Marchesini, Massimo Lopez and Tullio Solenghi).

See also

References

- Archibald Colquhoun. Manzoni and his Times. J. M. Dent & Sons, London, 1954.

- http://opera.stanford.edu/Ponchielli/ Stanford University (website); List of operas written by Amilcare Ponchielli (accessed 16 August 2012)

- Sebastian Werr: Die Opern von Errico Petrella; Edition Praesens, Vienna, 1999

- De Berti, Raffaele; Bertellini, Giorgio (17 March 2018). "Milano Films: The Exemplary History of a Film Company of the 1910s". Film History. 12 (3): 276–287. JSTOR 3815357.

- "The Spirit and the Flesh". 30 October 1948 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Renzo e Lucia". 13 January 2004 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Manzoni had taken a book to read on holiday to Brusuglio, which contained the edict. It is also printed in Melchiorre Gioia's Economia e Statistica.

- Jean Pierre Barricelli. Alessandro Manzoni. Twayne, Boston, 1976.

- In September 1832, Manzoni wrote in a letter to his friend Cesare Cantù: "L'Innominato è certamente Bernardino Visconti. Per l'æqua potestas quidlibet audendi ho trasportato il suo castello nella Valsassina." ("The Unnamed is certainly Bernardino Visconti. For the equal right to dare to do anything [a reference to Horace's Ars Poetica, v. 10], I transported his castle in the Valsassina"). The letter is number 1613 (page 443) in the 1986 edition by Cesare Arieti & Dante Isella of Manzoni's letters.

- Amelia, William (12 February 2011). "The Great Italian Novel, a Love Story" – via www.wsj.com.

- I Promessi sposi or The Betrothed Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Ezio Raimondi, Il romanzo senza idillio. Saggio sui Promessi Sposi, Einaudi, Torino, 1974

- From Georg Lukàcs, "The Historical Novel" (1969): "In Italy Scott found a successor who, though in a single, isolated work, nevertheless broadened his tendencies with superb originality, in some respect surpassing him. We refer, of course, to Manzoni's I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). Scott himself recognized Manzoni's greatness. When in Milan Manzoni told him that he was his pupil, Scott replied that in that case Manzoni's was his best work. It is, however, very characteristic that while Scott was able to write a profusion of novels about English and Scottish society, Manzoni confined himself to this single masterpiece."

- Matthew Reynolds (2000). The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation. Oxford University Press. p. 490. ISBN 0-19-818359-3.

- Penham, Bruce (1972). "Introduction". The betrothed. New York: Penguin. p. 13. ISBN 014044274X.

External links

- A review of The Betrothed written by Edgar Allan Poe in 1835 and published in the Southern Literary Messenger.

- 1834 English translation of The Betrothed from Project Gutenberg

- 1844 English translation of The Betrothed

- Complete Italian text of I promessi sposi

- The Betrothed Map