Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany /ˈroʊməni/, /ˈrɒ-/), colloquially known as Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants living mostly in Europe, and diaspora populations in the Americas. The Romani as a people originate from the northern Indian subcontinent,[58][59][60] from the Rajasthan, Haryana, and Punjab regions of modern-day India.[59][60]

Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted by the 1971 World Romani Congress | |

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2–20 million[1][2][3][4] | |

| 1,000,000 estimated with Romani ancestry[note 1][5][6] | |

| 800,000[7] | |

| 750,000–1,100,000 (1.87%)[8][9][10][11][12] | |

| 619,007[note 2]-1,850,000 (8.63%)[13][9][14][15] | |

| 500,000–2,750,000 (3.78%)[9][16][17][18] | |

| 350,000–500,000[19][20] | |

| 325,343[note 3]–750,000 (10.33%)[21][22] | |

| 309,632[note 4]–870,000 (8.8%)[23][24] | |

| 300,000[note 5][25][26] | |

| 225,000 (0.36%)[27][9][28] | |

| 205,007[note 6]–825,000 (0.58%)[9] | |

| 147,604[note 7]–600,000 (8.23%)[29][30][9] | |

| 120,000–180,000 (0.3%)[31][9] | |

| 111,000–300,000 (2.7%)[32][33] | |

| 105,000 (0.13%)[9][34] | |

| 105,738[note 8]–490,000 (9.02%)[35][36][37] | |

| 100,000–110,000[38] | |

| 53,879[note 9]–197,000 (9.56%)[9][39] | |

| 50,000–100,000[9][40] | |

| 47,587[note 10]–260,000 (0.57%)[9][41] | |

| 40,000–52,000 (0.49%)[9][42] | |

| 40,000–50,000 (0.57%) | |

| 36,000[note 11] (2%)[9][43] | |

| 32,000–40,000 (0.24%)[9] | |

| 22,435–37,500 (0.84%)[9] | |

| 20,000[44] | |

| 17,049[note 6]–32,500 (0.09%)[9][45] | |

| 16,975[note 6]–35,000 (0.79%)[9][46] | |

| 15,850[47] | |

| 12,778[note 6]–107,100 (3.01%)[9][48] | |

| 10,000-12,000 est. (0.17%)[49] | |

| 8,864[note 6]–58,000 (1.54%)[9][50] | |

| 2,649-8,000[25][51] | |

| 8,301[note 12]–300,000 (4.59%)[9][42][52] | |

| 7,316[note 6]–47,500 (0.5%)[53] | |

| 7,193[note 6]–12,500 (0.56%)[9] | |

| 5,255–80,000[54][55] | |

| 5,251[note 6]–20,000 (3.7%)[56] | |

| Languages | |

| Romani language, Para-Romani varieties, languages of native regions | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity[57] Islam[57] Shaktism tradition of Hinduism[57] Romani mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dom, Lom, Domba; other Indo-Aryans | |

| Part of a series on |

| Romani people |

|---|

|

Diaspora

|

|

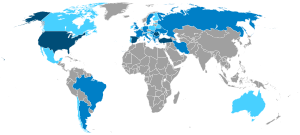

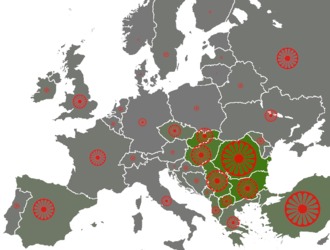

Genetic findings appear to confirm that the Romani "came from a single group that left northwestern India" in about 512 CE.[61] Genetic research published in the European Journal of Human Genetics "revealed that over 70% of males belong to a single lineage that appears unique to the Roma".[62] They are dispersed, but their most concentrated populations are located in Europe, especially Central, Eastern and Southern Europe (including Turkey, Spain and Southern France). The Romani arrived in Mid-West Asia and Europe around 1007.[63] They have been associated with another Indo-Aryan group, the Dom people: the two groups have been said to have separated from each other or, at least, to share a similar history.[64] Specifically, the ancestors of both the Romani and the Dom left North India sometime between the 6th and 11th century.[63]

The Romani are widely known in English by the exonym Gypsies (or Gipsies), which is considered by some Roma people to be pejorative due to its connotations of illegality and irregularity.[65] Beginning in 1888, the Gypsy Lore Society[66] started to publish a journal that was meant to dispel rumors about their lifestyle.[67]

Since the 19th century, some Romani have also migrated to the Americas. There are an estimated one million Roma in the United States;[6] and 800,000 in Brazil, most of whose ancestors emigrated in the 19th century from Eastern Europe. Brazil also includes a notable Romani community descended from people deported by the Portuguese Empire during the Portuguese Inquisition.[68] In migrations since the late 19th century, Romani have also moved to other countries in South America and to Canada.[69]

In February 2016, during the International Roma Conference, the Indian Minister of External Affairs stated that the people of the Roma community were children of India.[70] The conference ended with a recommendation to the government of India to recognize the Roma community spread across 30 countries as a part of the Indian diaspora.[71]

The Romani language is divided into several dialects which together have an estimated number of speakers of more than two million.[72] The total number of Romani people is at least twice as high (several times as high according to high estimates). Many Romani are native speakers of the dominant language in their country of residence or of mixed languages combining the dominant language with a dialect of Romani; those varieties are sometimes called Para-Romani.[73]

Names

Exonyms

Perceived as derogatory, many of these exonyms are falling out of standard usage and being replaced by a version of the name Roma.

- English tzigane (for Hungarian gypsies)

- Manx shingaarey

- Spanish zíngaro, cíngaro or gitanos

- French tzigane

- Old High German zigeuner

- German Zigeuner

- Dutch zigeuner

- Danish sigøjner

- Swedish zigenare, tattare

- Norwegian sigøynere

- Old Church Slavic ациганинъ atsyganin

- Italian zingaro

- Romanian țigan

- Hungarian cigány

- Serbo-Croatian cigan, ciganin

- Albanian cigan

- Polish Cygan

- Czech cikán

- Portuguese cigano, zíngaro

- Turkish çigan, more recently çingene

- Azerbaijani çıqan

- Slovak cigán or cigáň

- Venetian singano

- Russian цыгане tsygane

- Belarusian цыганы cyhany

- Ukrainian and Macedonian цигани tsyhany

- Bulgarian цигани tsigani

- Lithuanian čigonai

- Latvian čigāni

- Georgian ციგანი; from Greek ἀθίγγανος athínganos (corrupted form: τσιγγάνος tsingános), "untouchable".[74][75][76][77] Due to the negative connotations of referring to an ethnic group as "untouchable" words derived from this source are usually considered derogatory and outdated by modern Roma peoples.

- French bohème, bohémien, from the Kingdom of Bohemia, where they were incorrectly believed to have come from,[78][79] carrying writs of protection from King Sigismund of Bohemia.[74]

- French gitan, English gypsy, gipsy /ˈdʒɪpsiː/, Irish giofóg, Spanish/Catalan/Italian/Portuguese gitano, Basque ijito, Turkish çingene, all from Greek Αἰγύπτιος Aigýptios "Egyptian" (corrupted form: Γύφτος Gýftos), and Hungarian fáraónépe from Greek φαραώ pharaó "pharaoh" – referring to their allegedly Egyptian provenance.[74] Usage of "gypsy" and similarly derived words differs between groups as some Roma groups use this word as a self-identifier, especially in the United Kingdom,[80][81][82] while others, especially in the United States, consider this word a racial slur.[65]

- Albanian Jevg (referring to Roma who speak Albanian), evgjit (From the plural form of jevg: jevgjit), gabel (referring to nomadic groups, they predominantly speak Romani), Magjup (commonly used in Korça, Roma of Egyptian origin)

- Arabic (Standard): غَجَر /ɣad͡ʒar/ ḡajar, (dialectal) نَوَر Nawar and زُطّ Zott.

- Finnish mustalainen and Estonian mustlane (from must(a) "black")

- Persian Koli (كولی)

- Hebrew Tzoanim (צוענים). Derives either from the biblical Egyptian city of Zoan, or from the linguistic root צ־ע־נ, meaning "wander".

- Azerbaijani qaraçı (derives from the Azeri word qara – "black" and the suffix -çı denoting the stem-word's function/occupation)

- Kurdish Qaraj (قەرەج)

- Egyptian Arabic ghager (غجر)

Endonyms

Rom means man or husband in the Romani language. It has the variants dom and lom, which may be related to the Sanskrit words dam-pati (lord of the house, husband), dama (to subdue), lom (hair), lomaka (hairy), loman, roman (hairy), romaça (man with beard and long hair).[83] Another possible origin is from Sanskrit डोम doma (member of a low caste of travelling musicians and dancers).

Romani usage

In the Romani language, Rom is a masculine noun, meaning 'man of the Roma ethnic group' or 'man, husband', with the plural Roma. The feminine of Rom in the Romani language is Romni. However, in most cases, in other languages Rom is now used for people of both genders.[84]

Romani is the feminine adjective, while Romano is the masculine adjective. Some Romanies use Rom or Roma as an ethnic name, while others (such as the Sinti, or the Romanichal) do not use this term as a self-ascription for the entire ethnic group.[85]

Sometimes, rom and romani are spelled with a double r, i.e., rrom and rromani. In this case rr is used to represent the phoneme /ʀ/ (also written as ř and rh), which in some Romani dialects has remained different from the one written with a single r. The rr spelling is common in certain institutions (such as the INALCO Institute in Paris), or used in certain countries, e.g., Romania, to distinguish from the endonym/homonym for Romanians (sg. român, pl. români).[86]

English usage

In the English language (according to the Oxford English Dictionary), Rom is a noun (with the plural Roma or Roms) and an adjective, while Romani (Romany) is also a noun (with the plural Romani, the Romani, Romanies, or Romanis) and an adjective. Both Rom and Romani have been in use in English since the 19th century as an alternative for Gypsy.[87] Romani was sometimes spelled Rommany, but more often Romany, while today Romani is the most popular spelling. Occasionally, the double r spelling (e.g., Rroma, Rromani) mentioned above is also encountered in English texts.

The term Roma is increasingly encountered,[88][89] as a generic term for the Romani people.[90][91][92]

Because all Romanis use the word Romani as an adjective, the term became a noun for the entire ethnic group.[93] Today, the term Romani is used by some organizations, including the United Nations and the US Library of Congress.[86] However, the Council of Europe and other organizations consider that Roma is the correct term referring to all related groups, regardless of their country of origin, and recommend that Romani be restricted to the language and culture: Romani language, Romani culture.[84]

The standard assumption is that the demonyms of the Romani people, Lom and Dom share the same origin.[94][95]

Other designations

The English term Gypsy (or Gipsy) originates from the Middle English gypcian, short for Egipcien. The Spanish term Gitano and French Gitan have similar etymologies. They are ultimately derived from the Greek Αιγύπτιοι (Aigyptioi), meaning Egyptian, via Latin. This designation owes its existence to the belief, common in the Middle Ages, that the Romani, or some related group (such as the Middle Eastern Dom people), were itinerant Egyptians.[96][97] This belief appears to derive from verses in the biblical Book of Ezekiel (29: 6 and 12-13) referring to the Egyptians being scattered among the nations by an angry God. According to one narrative, they were exiled from Egypt as punishment for allegedly harbouring the infant Jesus.[98] In his book 'The Zincali: an account of the Gypsies of Spain', George Borrow notes that when they first appeared in Germany it was under the character of Egyptians doing penance for their having refused hospitality to the Virgin and her son. As described in Victor Hugo's novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the medieval French referred to the Romanies as Egyptiens.

This exonym is sometimes written with capital letter, to show that it designates an ethnic group.[99] However, the word is considered derogatory because of its negative and stereotypical associations.[91][100][101][102] The Council of Europe consider that "Gypsy" or equivalent terms, as well as administrative terms such as "Gens du Voyage" (referring in fact to an ethnic group but not acknowledging ethnic identification) are not in line with European recommendations.[84] In North America, the word Gypsy is most commonly used as a reference to Romani ethnicity, though lifestyle and fashion are at times also referenced by using this word.[103]

Another common designation of the Romani people is Cingane (alt. Tsinganoi, Zigar, Zigeuner), which likely derives from Athinganoi, the name of a Christian sect with whom the Romani (or some related group) became associated in the Middle Ages.[97][104][105][106]

Population and subgroups

Romani population

For a variety of reasons, many Romanis choose not to register their ethnic identity in official censuses. There are an estimated 10 million Romani people in Europe (as of 2019),[107] although some high estimates by Romani organizations give numbers as high as 14 million.[108] Significant Romani populations are found in the Balkans, in some Central European states, in Spain, France, Russia and Ukraine. In the European Union there are an estimated 6 million Romanis.[109] Several million more Romanis may live outside Europe, in particular in the Middle East and in the Americas.[110]

Romani subgroups

Like the Roma in general, many different ethnonyms are given to subgroups of Roma. Sometimes a subgroup uses more than one endonym, is commonly known by an exonym or erroneously by the endonym of another subgroup. The only name approaching an all-encompassing self-description is Rom.[111] Even when subgroups don't use the name, they all acknowledge a common origin and a dichotomy between themselves and Gadjo (non-Roma).[111] For instance, while the main group of Roma in German-speaking countries refer to themselves as Sinti, their name for their original language is Romanes.

Subgroups have been described as, in part, a result of the castes and subcastes in India, which the founding population of Rom almost certainly experienced in their South Asian urheimat.[111][112]

.jpg)

Many groups use names apparently derived from the Romani word kalo or calo, meaning "black" or "absorbing all light".[113] This closely resembles words for "black" or "dark" in Indo-Aryan languages (e.g., Sanskrit काल kāla: "black", "of a dark colour").[111] Likewise, the name of the Dom or Domba people of North India – to whom the Roma have genetic,[114] cultural and linguistic links – has come to imply "dark-skinned", in some Indian languages.[115] Hence names such as kale and calé may have originated as an exonym or a euphemism for Roma.

Other endonyms for Romani include, for example:

- Ashkali (or "Balkan Egyptians") – Albanian-speaking Roma communities in the Balkans[116]

- Bashaldé – Hungarian-Slovak Roma diaspora in the US from the late 19th century.[117]

- Calé is the endonym used by both the Spanish Roma (gitanos) and Portuguese Roma ciganos;[118] Caló is "the language spoken by the calé".

- Erlides (also Arlije, Yerlii or Arli) in Greece

- Kaale, in Finland and Sweden.[118][111]

- Kale, Kalá, or Valshanange – Welsh English endonym used by some Roma clans in Wales.[119] (Romanichal also live in Wales.) Romani in Spain are also attributed to the Kale.[12]

- Khorakhanè, Horahane or Xoraxai, also known as "Turkish Roma" or "Muslim Roma" – Greek Roma and Turkish Roma.[111]

- Lalleri, from Austria, Germany, and the western Czech Republic (including the former Sudetenland).

- Lovari, from Hungary,[120] known in Serbia as Machvaya, Machavaya, Machwaya, or Macwaia. [111]

- Lyuli, in Central Asian countries.

- Rom in Italy.

- Roma in Romania, commonly known by majority ethnic Romanians as Țigani, including many subgroups defined by occupation:

- Boyash, also known as Băieși, Lingurari, Ludar, Ludari, or Rudari, who coalesced in the Apuseni Mountains of Transylvania. Băieși is a Romanian word for "miners". Lingurari means "spoon makers",[121] Ludar, Ludari, and Rudari may mean "woodworkers" or "miners".[122] (There is a semantic overlap due to the homophony or merging of lemmas with different meanings from at least two different languages: the Serbian rudar miner, and ruda stick, staff, rod, bar, pole (in Hungarian rúd,[123] and in Romanian rudă).[124])

- Churari,[125] from Romanian Ciurari, "sieve makers", Zlătari "gold smiths"[111]

- Ursari (bear trainers, from Moldovan/Romanian urs "bear"),[111]

- Ungaritza blacksmiths and bladesmiths

- Argintari silversmiths.

- Aurari goldsmiths.

- Florari flower sellers.

- Lăutari singers.

- Kalderash, from Romanian căldărar, lit. bucketmaker, meaning kettlemaker, tinsmith, tinker; also in Moldova and Ukraine.

- Roma or Romové, Czech Republic

- Roma or Rómovia, Slovakia

- Romanichal, in the United Kingdom,[118][111] emigrated also to the United States, Canada and Australia[126]

- Romanisæl, in Norway and Sweden.

- Roms or Manouche (from manush "people" in Romani) in France.[111][127]

- Romungro or Carpathian Romani from eastern Hungary and neighbouring parts of the Carpathians[128]

- Sinti or Zinti, predominantly in Germany,[118][111] and Northern Italy; Sinti do not refer to themselves as Roma, although their language is called Romanes.[111]

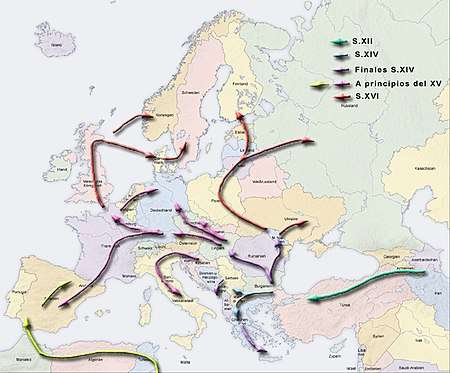

Diaspora

The Roma people have a number of distinct populations, the largest being the Roma and the Iberian Calé or Caló, who reached Anatolia and the Balkans about the early 12th century, from a migration out of northwestern India beginning about 600 years earlier.[129][61] They settled in present-day Turkey, Greece, Serbia, Romania, Moldova, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Hungary and Slovakia, by order of volume, and Spain. From the Balkans, they migrated throughout Europe and, in the nineteenth and later centuries, to the Americas. The Romani population in the United States is estimated at more than one million.[130] Brazil has the second largest Romani population in the Americas, estimated at approximately 800,000 by the 2011 census. The Romani people are mainly called by non-Romani ethnic Brazilians as ciganos. Most of them belong to the ethnic subgroup Calés (Kale), of the Iberian peninsula. Juscelino Kubitschek, Brazilian president during 1956–1961 term, was 50% Czech Romani by his mother's bloodline; and Washington Luís, last president of the First Brazilian Republic (1926–1930 term), had Portuguese Kale ancestry.

There is no official or reliable count of the Romani populations worldwide.[131] Many Romani refuse to register their ethnic identity in official censuses for fear of discrimination.[132] Others are descendants of intermarriage with local populations and no longer identify only as Romani, or not at all.

As of the early 2000s, an estimated 3.8[133] to 9 million Romani people lived in Europe and Asia Minor.[134] although some Romani organizations estimate numbers as high as 14 million.[135] Significant Romani populations are found in the Balkan peninsula, in some Central European states, in Spain, France, Russia, and Ukraine. The total number of Romani living outside Europe are primarily in the Middle East and North Africa and in the Americas, and are estimated in total at more than two million. Some countries do not collect data by ethnicity.

The Romani people identify as distinct ethnicities based in part on territorial, cultural and dialectal differences, and self-designation.[136][137][138][139]

Origin

Genetic findings suggest an Indian origin for Roma.[129][61][140] Because Romani groups did not keep chronicles of their history or have oral accounts of it, most hypotheses about the Romani's migration early history are based on linguistic theory.[141] There is also no known record of a migration from India to Europe from medieval times that can be connected indisputably to Roma.[142]

Shahnameh legend

According to a legend reported in the Persian epic poem, the Shahnameh, from Iran and repeated by several modern authors, the Sasanian king Bahrām V Gōr learned towards the end of his reign (421–39) that the poor could not afford to enjoy music, and he asked the king of India to send him ten thousand luris, lute-playing experts. When the luris arrived, Bahrām gave each one an ox, a donkey, and a donkey-load of wheat so that they could live on agriculture and play music for free for the poor. But the luris ate the oxen and the wheat and came back a year later with their cheeks hollowed with hunger. The king, angered with their having wasted what he had given them, ordered them to pack up their bags and go wandering around the world on their donkeys.[143]

Linguistic evidence

The linguistic evidence has indisputably shown that the roots of the Romani language lie in India: the language has grammatical characteristics of Indian languages and shares with them a large part of the basic lexicon, for example, regarding body parts or daily routines.[144]

More exactly, Romani shares the basic lexicon with Hindi and Punjabi. It shares many phonetic features with Marwari, while its grammar is closest to Bengali.[145]

Romani and Domari share some similarities: agglutination of postpositions of the second Layer (or case marking clitics) to the nominal stem, concord markers for the past tense, the neutralisation of gender marking in the plural, and the use of the oblique case as an accusative.[146] This has prompted much discussion about the relationships between these two languages. Domari was once thought to be a "sister language" of Romani, the two languages having split after the departure from the Indian subcontinent – but later research suggests that the differences between them are significant enough to treat them as two separate languages within the Central zone (Hindustani) group of languages. The Dom and the Rom therefore likely descend from two different migration waves out of India, separated by several centuries.[64][147]

In phonology, Romani language shares several isoglosses with the Central branch of Indo-Aryan languages especially in the realization of some sounds of the Old Indo-Aryan. However, it also preserves several dental clusters. In regards to verb morphology, Romani follows exactly the same pattern of northwestern languages such as Kashmiri and Shina through the adoption of oblique enclitic pronouns as person markers, lending credence to the theory of their Central Indian origin and a subsequent migration to northwestern India. Though the retention of dental clusters suggests a break from central languages during the transition from Old to Middle Indo-Aryan, the overall morphology suggests that the language participated in some of the significant developments leading toward the emergence of New Indo-Aryan languages.[148] Numerals in the Romani, Domari and Lomavren languages, with Sanskrit, Hindi and Persian forms for comparison.[149] Note that Romani 7–9 are borrowed from Greek.

| languages→ | Sanskrit | Hindi | Romani | Domari | Lomavren | Persian |

| ↓ numbers | ||||||

| 1 | éka | ek | ekh, jekh | yika | yak, yek | yak, yek |

| 2 | dvá | do | duj | dī | lui | du, do |

| 3 | trí | tīn | trin | tærən | tərin | se |

| 4 | catvā́raḥ | cār | štar | štar | išdör | čahār |

| 5 | páñca | pā̃c | pandž | pandž | pendž | pandž |

| 6 | ṣáṭ | chah | šov | šaš | šeš | šeš |

| 7 | saptá | sāt | ifta | xaut | haft | haft |

| 8 | aṣṭá | āṭh | oxto | xaišt | hašt | hašt |

| 9 | náva | nau | inja | na | nu | noh |

| 10 | dáśa | das | deš | des | las | dah |

| 20 | viṃśatí | bīs | biš | wīs | vist | bist |

| 100 | śatá | sau | šel | saj | saj | sad |

Genetic evidence

Genetic findings in 2012 suggest the Romani originated in northwestern India and migrated as a group.[129][61][150] According to the study, the ancestors of present scheduled castes and scheduled tribes populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Ḍoma, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma.[151] In December 2012, additional findings appeared to confirm the "Roma came from a single group that left northwestern India about 1,500 years ago".[61] They reached the Balkans about 900 years ago[129] and then spread throughout Europe. The team also found the Roma to display genetic isolation, as well as "differential gene flow in time and space with non-Romani Europeans".[129][61]

Genetic research published in European Journal of Human Genetics "has revealed that over 70% of males belong to a single lineage that appears unique to the Roma".[62]

Genetic evidence supports the medieval migration from India. The Romani have been described as "a conglomerate of genetically isolated founder populations",[152] while a number of common Mendelian disorders among Romanies from all over Europe indicates "a common origin and founder effect".[152][153]

A study from 2001 by Gresham et al. suggests "a limited number of related founders, compatible with a small group of migrants splitting from a distinct caste or tribal group".[154] The same study found that "a single lineage... found across Romani populations, accounts for almost one-third of Romani males".[154] A 2004 study by Morar et al. concluded that the Romani population "was founded approximately 32–40 generations ago, with secondary and tertiary founder events occurring approximately 16–25 generations ago".[155]

Haplogroup H-M82 is a major lineage cluster in the Balkan Romani group, accounting for approximately 60% of the total.[156] Haplogroup H is uncommon in Europe but present in the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka.

A study of 444 people representing three different ethnic groups in North Macedonia found mtDNA haplogroups M5a1 and H7a1a were dominant in Romanies (13.7% and 10.3%, respectively).[157]

Y-DNA composition of Romani in North Macedonia, based on 57 samples:[158]

- Haplogroup H – 59.6%

- Haplogroup E – 29.8%

- Haplogroup I – 5.3%

- Haplogroup R – 3.%, of which the half are R1b and many are R1a

- Haplogroup G – 1.8%

Y-DNA Haplogroup H1a occurs in Romani at frequencies 7–70%. Unlike ethnic Hungarians, among Hungarian and Slovakian Romani subpopulations, Haplogroup E-M78 and I1 usually occur above 10% and sometimes over 20%. While among Slovakian and Tiszavasvari Romani the dominant haplogroup is H1a, among Tokaj Romani is Haplogroup J2a (23%), while among Taktaharkány Romani is Haplogroup I2a (21%).[159] Five, rather consistent founder lineages throughout the subpopulations, were found among Romani – J-M67 and J-M92 (J2), H-M52 (H1a1), and I-P259 (I1?). Haplogroup I-P259 as H is not found at frequencies of over 3 percent among host populations, while haplogroups E and I are absent in South Asia. The lineages E-V13, I-P37 (I2a) and R-M17 (R1a) may represent gene flow from the host populations. Bulgarian, Romanian and Greek Romani are dominated by Haplogroup H-M82 (H1a1), while among Spanish Romani J2 is prevalent.[160] In Serbia among Kosovo[lower-alpha 1] and Belgrade Romani Haplogroup H prevails, while among Vojvodina Romani, H drops to 7 percent and E-V13 rises to a prevailing level.[161]

Among non-Roma Europeans Haplogroup H is extremely rare, peaking at 7 percent among Albanians from Tirana[162] and 11 percent among Bulgarian Turks. It occurs at 5 percent among Hungarians,[159] although the carriers might be of Romani origin.[160] Among non Roma-speaking Europeans at 2 percent among Slovaks,[163] 2 percent among Croats,[164] 1 percent among Macedonians from Skopje, 3 percent among Macedonian Albanians,[165] 1 percent among Serbs from Belgrade,[166] 3 percent among Bulgarians from Sofia,[167] 1 percent among Austrians and Swiss,[168] 3 percent among Romanians from Ploiesti, 1 percent among Turks.[163]

Possible migration route

They may have emerged from the modern Indian state of Rajasthan,[169] migrating to the northwest (the Punjab region, Sindh and Baluchistan of the Indian subcontinent) around 250 BC. Their subsequent westward migration, possibly in waves, is now believed to have occurred beginning in about CE 500.[61] It has also been suggested that emigration from India may have taken place in the context of the raids by Mahmud of Ghazni. As these soldiers were defeated, they were moved west with their families into the Byzantine Empire.[170] The author Ralph Lilley Turner theorised a central Indian origin of Romani followed by a migration to Northwest India as it shares a number of ancient isoglosses with Central Indo-Aryan languages in relation to realization of some sounds of Old Indo-Aryan. This is lent further credence by its sharing exactly the same pattern of northwestern languages such as Kashmiri and Shina through the adoption of oblique enclitic pronouns as person markers. The overall morphology suggests that Romani participated in some of the significant developments leading toward the emergence of New Indo-Aryan languages, thus indicating that the proto-Romani did not leave the Indian subcontinent until late in the second half of the first millennium.[148][171]

History

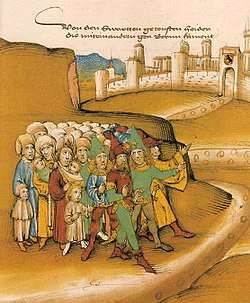

Arrival in Europe

Though according to a 2012 genomic study, the Romani reached the Balkans as early as the 12th century,[172] the first historical records of the Romani reaching south-eastern Europe are from the 14th century: in 1322, after leaving Ireland on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, Irish Franciscan friar Symon Semeonis encountered a migrant group of Romani outside the town of Candia (modern Heraklion), in Crete, calling them "the descendants of Cain"; his account is the earliest surviving description by a Western chronicler of the Romani in Europe.

In 1350, Ludolph of Saxony mentioned a similar people with a unique language whom he called Mandapolos, a word some think derives from the Greek word mantes (meaning prophet or fortune teller).[173]

Around 1360, a fiefdom called the Feudum Acinganorum was established in Corfu, which mainly used Romani serfs and to which the Romani on the island were subservient.[174]

By the 1440s, they were recorded in Germany;[175] and by the 16th century, Scotland and Sweden.[176] Some Romani migrated from Persia through North Africa, reaching the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century. The two currents met in France.[177]

Early modern history

Their early history shows a mixed reception. Although 1385 marks the first recorded transaction for a Romani slave in Wallachia, they were issued safe conduct by Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund in 1417. Romanies were ordered expelled from the Meissen region of Germany in 1416, Lucerne in 1471, Milan in 1493, France in 1504, Catalonia in 1512, Sweden in 1525, England in 1530 (see Egyptians Act 1530), and Denmark in 1536. In 1510, any Romani found in Switzerland were ordered put to death, with similar rules established in England in 1554, and Denmark in 1589, whereas Portugal began deportations of Romanies to its colonies in 1538.[179]

A 1596 English statute gave Romanis special privileges that other wanderers lacked. France passed a similar law in 1683. Catherine the Great of Russia declared the Romanies "crown slaves" (a status superior to serfs), but also kept them out of certain parts of the capital.[180] In 1595, Ștefan Răzvan overcame his birth into slavery, and became the Voivode (Prince) of Moldavia.[179]

Since a royal edict by Charles II in 1695, Spanish Romanis had been restricted to certain towns.[181] An official edict in 1717 restricted them to only 75 towns and districts, so that they would not be concentrated in any one region. In the Great Gypsy Round-up, Romani were arrested and imprisoned by the Spanish Monarchy in 1749.

During the latter part of the 17th century, around the Franco-Dutch War, both France and Holland needed thousands of men to fight. Some recruitment took the form of rounding up vagrants and the poor to work the galleys and provide the armies' labour force. With this background, Romanis were targets of both the French and the Dutch.

After the wars, and into the first decade of the 18th century, Romanis were slaughtered with impunity throughout Holland. Romanis, called ‘heiden’ by the Dutch, wandered throughout the rural areas of Europe and became the societal pariahs of the age. Heidenjachten, translated as "heathen hunt" happened throughout Holland in an attempt to eradicate them.[182]

Although some Romani could be kept as slaves in Wallachia and Moldavia until abolition in 1856, the majority traveled as free nomads with their wagons, as alluded to in the spoked wheel symbol in the Romani flag.[183] Elsewhere in Europe, they were subjected to ethnic cleansing, abduction of their children, and forced labour. In England, Romani were sometimes expelled from small communities or hanged; in France, they were branded, and their heads were shaved; in Moravia and Bohemia, the women were marked by their ears being severed. As a result, large groups of the Romani moved to the East, toward Poland, which was more tolerant, and Russia, where the Romani were treated more fairly as long as they paid the annual taxes.[184]

Modern history

Romani began emigrating to North America in colonial times, with small groups recorded in Virginia and French Louisiana. Larger-scale Roma emigration to the United States began in the 1860s, with Romanichal groups from Great Britain. The most significant number immigrated in the early 20th century, mainly from the Vlax group of Kalderash. Many Romani also settled in South America.

World War II

During World War II, the Nazis embarked on a systematic genocide of the Romani, a process known in Romani as the Porajmos.[185] Romanies were marked for extermination and sentenced to forced labor and imprisonment in concentration camps. They were often killed on sight, especially by the Einsatzgruppen (paramilitary death squads) on the Eastern Front.[186] The total number of victims has been variously estimated at between 220,000 and 1,500,000.[187]

The treatment of the Romani in Nazi puppet states differed markedly. In the Independent State of Croatia, the Ustaša killed almost the entire Roma population of 25,000. The concentration camp system of Jasenovac, run by the Ustaša militia and the Croat political police, were responsible for the deaths of between 15,000 and 20,000 Roma.[188]

Post-1945

In Czechoslovakia, they were labeled a "socially degraded stratum", and Romani women were sterilized as part of a state policy to reduce their population. This policy was implemented with large financial incentives, threats of denying future welfare payments, with misinformation, or after administering drugs.[189][190]

An official inquiry from the Czech Republic, resulting in a report (December 2005), concluded that the Communist authorities had practised an assimilation policy towards Romanis, which "included efforts by social services to control the birth rate in the Romani community. The problem of sexual sterilisation carried out in the Czech Republic, either with improper motivation or illegally, exists," said the Czech Public Defender of Rights, recommending state compensation for women affected between 1973 and 1991.[191] New cases were revealed up until 2004, in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland "all have histories of coercive sterilization of minorities and other groups".[192]

Society and traditional culture

The traditional Romanies place a high value on the extended family. Virginity is essential in unmarried women. Both men and women often marry young; there has been controversy in several countries over the Romani practise of child marriage. Romani law establishes that the man's family must pay a bride price to the bride's parents, but only traditional families still follow it.

Once married, the woman joins the husband's family, where her main job is to tend to her husband's and her children's needs and take care of her in-laws. The power structure in the traditional Romani household has at its top the oldest man or grandfather, and men, in general, have more authority than women. Women gain respect and power as they get older. Young wives begin gaining authority once they have children.

Romani social behavior is strictly regulated by Indian social customs[193] ("marime" or "marhime"), still respected by most Roma (and by most older generations of Sinti). This regulation affects many aspects of life and is applied to actions, people and things: parts of the human body are considered impure: the genital organs (because they produce emissions) and the rest of the lower body. Clothes for the lower body, as well as the clothes of menstruating women, are washed separately. Items used for eating are also washed in a different place. Childbirth is considered impure and must occur outside the dwelling place. The mother is deemed to be impure for forty days after giving birth.

Death is considered impure, and affects the whole family of the dead, who remain impure for a period of time. In contrast to the practice of cremating the dead, Romani dead must be buried.[194] Cremation and burial are both known from the time of the Rigveda, and both are widely practiced in Hinduism today (although the tendency is for Hindus to practice cremation, while some communities in South India tend to bury their dead).[195] Animals that are considered to be having unclean habits are not eaten by the community.[196]

Belonging and exclusion

In Romani philosophy, Romanipen (also romanypen, romanipe, romanype, romanimos, romaimos, romaniya) is the totality of the Romani spirit, Romani culture, Romani Law, being a Romani, a set of Romani strains.

An ethnic Romani is considered a gadjo in the Romani society if he has no Romanipen. Sometimes a non-Romani may be considered a Romani if he has Romanipen. Usually this is an adopted child. It has been hypothesized that it owes more to a framework of culture rather than simply an adherence to historically received rules.[197]

Religion

Most Romani people are Christian,[198] others Muslim; some retained their ancient faith of Hinduism from their original homeland of India, while others have their own religion and political organization.[199]

Beliefs

The ancestors of modern-day Romani people were Hindu, but adopted Christianity or Islam depending on the regions through which they had migrated.[200] Muslim Roma are found in Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Egypt, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Bulgaria, forming a very significant proportion of the Romani people. In neighboring countries such as Serbia and Greece, most Romani inhabitants follow the practice of Orthodoxy. It is likely that the adherence to differing religions prevented families from engaging in intermarriage.[201]

In Spain, most Gitanos are Roman Catholics. Some brotherhoods have organized Gitanos in their Holy Week devotions. They are popularly known as Cofradía de los Gitanos. However, the proportion of followers of Evangelical Christianity among Gitanos is higher than among the rest of Spaniards. Their version of el culto integrates Flamenco music.

Deities and saints

Blessed Ceferino Giménez Malla is recently considered a patron saint of the Romani people in Roman Catholicism.[202] Saint Sarah, or Sara e Kali, has also been venerated as a patron saint in her shrine at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France. Since the turn of the 21st century, Sara e Kali is understood to have been Kali, an Indian deity brought from India by the refugee ancestors of the Roma people; as the Roma became Christianized, she was absorbed in a syncretic way and venerated as a saint.[203]

Saint Sarah is now increasingly being considered as "a Romani Goddess, the Protectress of the Roma" and an "indisputable link with Mother India".[203][204]

Ceremonies and practices

Romanies often adopt the dominant religion of their host country in the event that a ceremony associated with a formal religious institution is necessary, such as a baptism or funeral (their particular belief systems and indigenous religion and worship remain preserved regardless of such adoption processes). The Roma continue to practice "Shaktism", a practice with origins in India, whereby a female consort is required for the worship of a god. Adherence to this practice means that for the Roma who worship the Christian God, prayer is conducted through the Virgin Mary, or her mother, Saint Anne. Shaktism continues over one thousand years after the people's separation from India.[205]

Besides the Roma elders (who serve as spiritual leaders), priests, churches, or bibles do not exist among the Romanies – the only exception is the Pentecostal Roma.[205]

Balkans

For the Roma communities that have resided in the Balkans for numerous centuries, often referred to as "Turkish Gypsies", the following histories apply for religious beliefs:

- Albania – The majority of Albania's Roma people are Muslims.[206]

- Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro – Islam is the dominant religion among the Roma.[207]

- Bulgaria – In northwestern Bulgaria, in addition to Sofia and Kyustendil, Christianity is the dominant faith among Romani people (a major conversion to Eastern Orthodox Christianity among Romani people has occurred). In southeastern Bulgaria, Islam is the dominant religion among Romani people, with a smaller section of the Romani population, declaring themselves as "Turks", continuing to mix ethnicity with Islam.[207]

- Croatia – Following the Second World War, a large number of Muslim Roma relocated to Croatia (the majority moving from Kosovo).[207]

- Greece – The descendants of groups, such as Sepečides or Sevljara, Kalpazaja, Filipidži and others, living in Athens, Thessaloniki, central Greece and Greek Macedonia are mostly Orthodox Christians, with Islamic beliefs held by a minority of the population. Following the Peace Treaty of Lausanne of 1923, many Muslim Roma moved to Turkey in the subsequent population exchange between Turkey and Greece.[207]

- Kosovo – The vast majority of the Roma population in Kosovo is Muslim.[207]

- North Macedonia – The majority of Roma people are followers of Islam.[207]

- Romania – According to the 2002 census, the majority of Romani minority living in Romania are Orthodox Christians, while 6.4% are Pentecostals, 3.8% Roman Catholics, 3% Reformed, 1.1% Greek Catholics, 0.9% Baptists, 0.8% Seventh-Day Adventists.[208] In Dobruja, there is a small community that are Muslim and also speak Turkish.[207]

- Serbia – Most Roma people in Serbia are Orthodox Christian, but there are some Muslim Roma in Southern Serbia, who are mainly refugees from Kosovo.[207]

Other regions

In Ukraine and Russia, the Roma populations are also Muslim as the families of Balkan migrants continue to live in these locations. Their ancestors settled on the Crimean peninsula during the 17th and 18th centuries, but then migrated to Ukraine, southern Russia and the Povolzhie (along the Volga River). Formally, Islam is the religion that these communities align themselves with and the people are recognized for their staunch preservation of the Romani language and identity.[207]

In Poland and Slovakia, their populations are Roman Catholic, many times adopting and following local, cultural Catholicism as a syncretic system of belief that incorporates distinct Roma beliefs and cultural aspects. For example, many Polish Roma delays their Church wedding due to the belief that sacramental marriage is accompanied by divine ratification, creating a virtually indissoluble union until the couple consummate, after which the sacramental marriage is dissoluble only by the death of a spouse. Therefore, for Polish Roma, once married, one can't ever divorce. Another aspect of Polish Roma's Catholicism is a tradition of pilgrimage to the Jasna Góra Monastery.[209]

Most Eastern European Romanies are Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, or Muslim.[210] Those in Western Europe and the United States are mostly Roman Catholic or Protestant – in southern Spain, many Romanies are Pentecostal, but this is a small minority that has emerged in contemporary times.[205] In Egypt, the Romanies are split into Christian and Muslim populations.[211]

Music

Romani music plays an important role in Central and Eastern European countries such as Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Albania, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia and Romania, and the style and performance practices of Romani musicians have influenced European classical composers such as Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms. The lăutari who perform at traditional Romanian weddings are virtually all Romani.

Probably the most internationally prominent contemporary performers in the lăutari tradition are Taraful Haiducilor. Bulgaria's popular "wedding music", too, is almost exclusively performed by Romani musicians such as Ivo Papasov, a virtuoso clarinetist closely associated with this genre and Bulgarian pop-folk singer Azis.

Many famous classical musicians, such as the Hungarian pianist Georges Cziffra, are Romani, as are many prominent performers of manele. Zdob și Zdub, one of the most prominent rock bands in Moldova, although not Romanies themselves, draw heavily on Romani music, as do Spitalul de Urgență in Romania, Shantel in Germany, Goran Bregović in Serbia, Darko Rundek in Croatia, Beirut and Gogol Bordello in the United States.

Another tradition of Romani music is the genre of the Romani brass band, with such notable practitioners as Boban Marković of Serbia, and the brass lăutari groups Fanfare Ciocărlia and Fanfare din Cozmesti of Romania.

Dances such as the flamenco of Spain and Oriental dances of Egypt are said to have originated from the Romani.[212]

The distinctive sound of Romani music has also strongly influenced bolero, jazz, and flamenco (especially cante jondo) in Spain. European-style gypsy jazz ("jazz Manouche" or "Sinti jazz") is still widely practiced among the original creators (the Romanie People); one who acknowledged this artistic debt was guitarist Django Reinhardt. Contemporary artists in this tradition known internationally include Stochelo Rosenberg, Biréli Lagrène, Jimmy Rosenberg, Paulus Schäfer and Tchavolo Schmitt.

The Romanies of Turkey have achieved musical acclaim from national and local audiences. Local performers usually perform for special holidays. Their music is usually performed on instruments such as the darbuka, gırnata and cümbüş.[213]

Contemporary art and culture

Romani contemporary art is art created by Romani people. It emerged at the climax of the process that began in Central and Eastern Europe in the late-1980s, when the interpretation of the cultural practice of minorities was enabled by a paradigm shift, commonly referred to in specialist literature as the Cultural turn. The idea of the "cultural turn" was introduced; and this was also the time when the notion of cultural democracy became crystallized in the debates carried on at various public forums. Civil society gained strength, and civil politics appeared, which is a prerequisite for cultural democracy. This shift of attitude in scholarly circles derived from concerns specific not only to ethnicity, but also to society, gender and class.[214]

Language

Most Romani speak one of several dialects of the Romani language,[215] an Indo-Aryan language, with roots in Sanskrit. They also often speak the languages of the countries they live in. Typically, they also incorporate loanwords and calques into Romani from the languages of those countries and especially words for terms that the Romani language does not have. Most of the Ciganos of Portugal, the Gitanos of Spain, the Romanichal of the UK, and Scandinavian Travellers have lost their knowledge of pure Romani, and respectively speak the mixed languages Caló,[216] Angloromany, and Scandoromani. Most of the speaker communities in these regions consist of later immigrants from eastern or central Europe.[217]

There are no concrete statistics for the number of Romani speakers, both in Europe and globally. However, a conservative estimation has been made at 3.5 million speakers in Europe and a further 500,000 elsewhere,[217] although the actual number may be considerably higher. This makes Romani the second largest minority language in Europe, behind Catalan.[217]

In relation to dialect diversity, Romani works in the same way as most other European languages.[218] Cross-dialect communication is dominated by the following features:

- All Romani speakers are bilingual, and are accustomed to borrowing words or phrases from a second language; this makes it difficult when trying to communicate with Romanis from different countries

- Romani was traditionally a language shared between extended family and a close-knit community. This has resulted in the inability to comprehend dialects from other countries. This is the reason Romani is sometimes considered to be several different languages.

- There is no tradition or literary standard for Romani speakers to use as a guideline for their language use.[218]

Persecutions

Historical persecution

One of the most enduring persecutions against the Romani people was their enslavement. Slavery was widely practiced in medieval Europe, including the territory of present-day Romania from before the founding of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in the 13th–14th century.[219] Legislation decreed that all the Romani living in these states, as well as any others who immigrated there, were classified as slaves.[220] Slavery was gradually abolished during the 1840s and 1850s.[221]

The exact origins of slavery in the Danubian Principalities are not known. There is some debate over whether the Romani people came to Wallachia and Moldavia as free men or were brought as slaves. Historian Nicolae Iorga associated the Roma people's arrival with the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe and considered their slavery as a vestige of that era, in which the Romanians took the Roma as slaves from the Mongols and preserved their status to use their labor. Other historians believe that the Romani were enslaved while captured during the battles with the Tatars. The practice of enslaving war prisoners may also have been adopted from the Mongols.[219]

Some Romani may have been slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars, but most of them migrated from south of the Danube at the end of the 14th century, some time after the foundation of Wallachia. By then, the institution of slavery was already established in Moldavia and possibly in both principalities. After the Roma migrated into the area, slavery became a widespread practice by the majority population. The Tatar slaves, smaller in numbers, were eventually merged into the Roma population.[222]

Some branches of the Romani people reached Western Europe in the 15th century, fleeing as refugees from the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans.[223] Although the Romani were refugees from the conflicts in southeastern Europe, they were often suspected by certain populations in the West of being associated with the Ottoman invasion because their physical appearance seemed Turkish. (The Imperial Diet at Landau and Freiburg in 1496–1498 declared that the Romani were spies of the Turks). In Western Europe, such suspicions and discrimination against a people who were a visible minority resulted in persecution, often violent, with efforts to achieve ethnic cleansing until the modern era. In times of social tension, the Romani suffered as scapegoats; for instance, they were accused of bringing the plague during times of epidemics.[224]

On 30 July 1749, Spain conducted The Great Roundup of Romani (Gitanos) in its territory. The Spanish Crown ordered a nationwide raid that led to the break-up of families as all able-bodied men were interned into forced labor camps in an attempt at ethnic cleansing. The measure was eventually reversed and the Romanis were freed as protests began to arise in different communities, sedentary romanis being highly esteemed and protected in rural Spain.[225][226]

Later in the 19th century, Romani immigration was forbidden on a racial basis in areas outside Europe, mostly in the English-speaking world. Argentina in 1880 prohibited immigration by Roma, as did the United States in 1885.[224]

Forced assimilation

In the Habsburg Monarchy under Maria Theresa (1740–1780), a series of decrees tried to force the Romanies to permanently settle, removed rights to horse and wagon ownership (1754), renamed them as "New Citizens" and forced Romani boys into military service if they had no trade (1761), forced them to register with the local authorities (1767), and prohibited marriage between Romanies (1773). Her successor Josef II prohibited the wearing of traditional Romani clothing and the use of the Romani language, punishable by flogging.[227]

In Spain, attempts to assimilate the Gitanos were under way as early as 1619, when Gitanos were forcibly settled, the use of the Romani language was prohibited, Gitano men and women were sent to separate workhouses and their children sent to orphanages. King Charles III took on a more progressive attitude to Gitano assimilation, proclaiming their equal rights as Spanish citizens and ending official denigration based on their race. While he prohibited the nomadic lifestyle, the use of the Calo language, Romani clothing, their trade in horses and other itinerant trades, he also forbade any form of discrimination against them or barring them from the guilds. The use of the word gitano was also forbidden to further assimilation, substituted for "New Castilian", which was also applied to former Jews and Muslims.[228][229]

Most historians agree that Charles III pragmática failed for three main reasons, ultimately derived from its implementation outside major cities and in marginal areas: The difficulty the Gitano community faced in changing its nomadic lifestyle, the marginal lifestyle in which the community had been driven by society and the serious difficulties of applying the pragmática in the fields of education and work. One author ascribes its failure to the overall rejection by the wider population of the integration of the Gitanos.[227][230]

Other examples of forced assimilation include Norway, where a law was passed in 1896 permitting the state to remove children from their parents and place them in state institutions.[231] This resulted in some 1,500 Romani children being taken from their parents in the 20th century.[232]

Porajmos (Holocaust)

The persecution of the Romanies reached a peak during World War II in the Porajmos genocide perpetrated by Nazi Germany. In 1935, the Nuremberg laws stripped the Romani people living in Nazi Germany of their citizenship, after which they were subjected to violence, imprisonment in concentration camps and later genocide in extermination camps. The policy was extended in areas occupied by the Nazis during the war, and it was also applied by their allies, notably the Independent State of Croatia, Romania, and Hungary.

Because no accurate pre-war census figures exist for the Romanis, it is impossible to accurately assess the actual number of victims. Most estimates for numbers of Romani victims of the Holocaust fall between 200,000 and 500,000, although figures ranging between 90,000 and 1.5 million have been proposed. Lower estimates do not include those killed in all Axis-controlled countries. A detailed study by Sybil Milton, formerly senior historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum gave a figure of at least a minimum of 220,000, possibly closer to 500,000.[233] Ian Hancock, Director of the Program of Romani Studies and the Romani Archives and Documentation Center at the University of Texas at Austin, argues in favour of a higher figure of between 500,000 and 1,500,000.[234]

In Central Europe, the extermination in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was so thorough that the Bohemian Romani language became extinct.

Contemporary issues

In Europe, Romani people are associated with poverty, and are accused of high rates of crime and behaviours that are perceived by the rest of the population as being antisocial or inappropriate.[236] Partly for this reason, discrimination against the Romani people has continued to the present day,[237][238] although efforts are being made to address them.[239] Amnesty International reports continued instances of Antizigan discrimination during the 20th century, particularly in Romania, Serbia,[240] Slovakia,[241] Hungary,[242] Slovenia,[243] and Kosovo.[244] The European Union has recognized that discrimination against Romani must be addressed, and with the national Roma integration strategy they encourage member states to work towards greater Romani inclusion and upholding the rights of the Romani in the European union.[245]

In Eastern Europe, Roma children often attend Roma Special Schools, separate from non-Roma children, which puts them at an educational disadvantage.[248]:83

The Romanis of Kosovo have been severely persecuted by ethnic Albanians since the end of the Kosovo War, and the region's Romani community is, for the most part, annihilated.[249]

Czechoslovakia carried out a policy of sterilization of Romani women, starting in 1973.[250] The dissidents of the Charter 77 denounced it in 1977–78 as a genocide, but the practice continued through the Velvet Revolution of 1989.[251] A 2005 report by the Czech Republic's independent ombudsman, Otakar Motejl, identified dozens of cases of coercive sterilization between 1979 and 2001, and called for criminal investigations and possible prosecution against several health care workers and administrators.[252]

In 2008, following the rape and subsequent murder of an Italian woman in Rome at the hands of a young man from a local Romani encampment,[253] the Italian government declared that Italy's Romani population represented a national security risk and that swift action was required to address the emergenza nomadi (nomad emergency).[254] Specifically, officials in the Italian government accused the Romanies of being responsible for rising crime rates in urban areas.

The 2008 deaths of Cristina and Violetta Djeordsevic, two Roma children who drowned while Italian beach-goers remained unperturbed, brought international attention to the relationship between Italians and the Roma people. Reviewing the situation in 2012, one Belgian magazine observed:

On International Roma Day, which falls on 8 April, the significant proportion of Europe's 12 million Roma who live in deplorable conditions will not have much to celebrate. And poverty is not the only worry for the community. Ethnic tensions are on the rise. In 2008, Roma camps came under attack in Italy, intimidation by racist parliamentarians is the norm in Hungary. Speaking in 1993, Václav Havel prophetically remarked that "the treatment of the Roma is a Litmus test for democracy": and democracy has been found wanting. The consequences of the transition to capitalism have been disastrous for the Roma. Under communism they had jobs, free housing and schooling. Now many are unemployed, many are losing their homes and racism is increasingly rewarded with impunity.[255]

The 2016 Pew Research poll found that Italians, in particular, hold strong anti-Roma views, with 82% of Italians expressing negative opinions about Roma. In Greece 67%, in Hungary 64%, in France 61%, in Spain 49%, in Poland 47%, in the UK 45%, in Sweden 42%, in Germany 40%, and in the Netherlands[256] 37% had an unfavourable view of Roma.[257] The 2019 Pew Research poll found that 83% of Italians, 76% of Slovaks, 72% of Greeks, 68% of Bulgarians, 66% of Czechs, 61% of Lithuanians, 61% of Hungarians, 54% of Ukrainians, 52% of Russians, 51% of Poles, 44% of French, 40% of Spaniards, and 37% of Germans held unfavorable views of Roma.[258]

Reports of anti-Roma incidents are increasing across Europe.[259] Discrimination against Roma remains widespread in Romania,[260] Slovakia,[261] Bulgaria,[262][263], and the Czech Republic.[264] Roma communities across Ukraine have been the target of violent attacks.[265][266]

Forced repatriation

In the summer of 2010, French authorities demolished at least 51 illegal Roma camps and began the process of repatriating their residents to their countries of origin.[267] This followed tensions between the French state and Roma communities, which had been heightened after French police opened fire and killed a traveller who drove through a police checkpoint, hitting an officer, and attempted to hit two more officers at another checkpoint. In retaliation a group of Roma, armed with hatchets and iron bars, attacked the police station of Saint-Aignan, toppled traffic lights and road signs and burned three cars.[268][269] The French government has been accused of perpetrating these actions to pursue its political agenda.[270] EU Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding stated that the European Commission should take legal action against France over the issue, calling the deportations "a disgrace". A leaked file dated 5 August, sent from the Interior Ministry to regional police chiefs, included the instruction: "Three hundred camps or illegal settlements must be cleared within three months, Roma camps are a priority."[271]

Organizations and projects

- World Romani Congress

- European Roma Rights Centre

- Gypsy Lore Society[66]

- International Romani Union

- Decade of Roma Inclusion, multinational project

- International Romani Day 8 April

Artistic representations

Many depictions of Romani people in literature and art present romanticized narratives of mystical powers of fortune telling or irascible or passionate temper paired with an indomitable love of freedom and a habit of criminality. Romani were a popular subject in Venetian painting from the time of Giorgione at the start of the 16th century; the inclusion of such a figure adds an exotic oriental flavour to scenes. A Venetian Renaissance painting by Paris Bordone (ca. 1530, Strasbourg) of the Holy Family in Egypt makes Elizabeth, a Romani fortune-teller; the scene is otherwise located in a distinctly European landscape.[272]

Particularly notable are classics like the story Carmen by Prosper Mérimée and the opera based on it by Georges Bizet, Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Herge's The Castafiore Emerald and Miguel de Cervantes' La Gitanilla. The Romani were also depicted in A Midsummer Night's Dream, As You Like It, Othello and The Tempest, all by William Shakespeare.

The Romani were also heavily romanticized in the Soviet Union, a classic example being the 1975 film Tabor ukhodit v Nebo. A more realistic depiction of contemporary Romani in the Balkans, featuring Romani lay actors speaking in their native dialects, although still playing with established clichés of a Romani penchant for both magic and crime, was presented by Emir Kusturica in his Time of the Gypsies (1988) and Black Cat, White Cat (1998). The films of Tony Gatlif, a French director of Romani ethnicity, like Les Princes (1983), Latcho Drom (1993) and Gadjo Dilo (1997) also portray romani life.

Paris Bordone, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt c. 1530, Elizabeth, at right, is shown as a Romani fortune-teller

Paris Bordone, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt c. 1530, Elizabeth, at right, is shown as a Romani fortune-teller August von Pettenkofen: Gypsy Children (1885), Hermitage Museum

August von Pettenkofen: Gypsy Children (1885), Hermitage Museum- Vincent van Gogh: The Caravans – Gypsy Camp near Arles (1888, oil on canvas)

_(4568143185).jpg)

Esméralda

Esméralda Nicolae Grigorescu Gypsy from Boldu (1897), Art Museum of Iași

Nicolae Grigorescu Gypsy from Boldu (1897), Art Museum of Iași

See also

- Environmental racism in Europe

- Gitanos

- Gypsy Scourge

- King of the Gypsies

- R v Krymowski

- Rajasthani people

- Timeline of Romani history

- Romani society and culture

General

Lists

Notes

- 5,400 per 2000 census.

- This is a census figure. Some 1,236,810 (6.14% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities.

- This is a census figure. Some 736,981 (10% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities. In a report of the census’ authors, the ethnic results of this census are identified as a "gross manipulation".

- This is a census figure. There was an option to declare multiple ethnicities, so this figure includes Romani of multiple backgrounds. According to the 2016 microcensus 99.1% of Hungarian Romani declared Hungarian ethnic identity also.

- Approximate estimate

- This is a census figure.

- This is a census figure. Some 368,136 (5.1% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities.

- This is a census figure. Some 408,777 (7.5% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities.

- This is a census figure. Less than 1% of the population did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities.

- This is a census figure. Less than 1% of the population did not declare any ethnicity.

- This is a census figure including Romani and Ashkali/Black Egyptians.

- This is a census figure. There was an additional 3,368 Balkan Egyptians. 390,938 (14% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. The census is regarded as unreliable by the Council of Europe

- Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 97 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 112 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition.

References

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World" (online) (16th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

Ian Hancock's 1987 estimate for 'all Gypsies in the world' was 6 to 11 million.

- "EU demands action to tackle Roma poverty". BBC News. 5 April 2011.

- "The Roma". Nationalia. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "Rom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

... estimates of the total world Roma population range from two million to five million.

- Smith, J. (2008). The marginalization of shadow minorities (Roma) and its impact on opportunities (Doctoral dissertation, Purdue University).

- Kayla Webley (13 October 2010). "Hounded in Europe, Roma in the U.S. Keep a Low Profile". Time. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

Today, estimates put the number of Roma in the U.S. at about one million.

- "Falta de políticas públicas para ciganos é desafio para o governo" [Lack of public policy for Romani is a challenge for the administration] (in Portuguese). R7. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

The Special Secretariat for the Promotion of Racial Equality estimates the number of "ciganos" (Romanis) in Brazil at 800,000 (2011). The 2010 IBGE Brazilian National Census encountered Romani camps in 291 of Brazil's 5,565 municipalities.

- "Roma integration in Spain". European Commission – European Commission.

- "Roma and Travellers Team. TOOLS AND TEXTS OF REFERENCE. Estimates on Roma population in European countries" (PDF)Council of Europe Roma and Travellers Division

- Estimated by the Society for Threatened Peoples

- "The Situation of Roma in Spain" (PDF). Open Society Institute. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

The Spanish government estimates the number of Gitanos at a maximum of 650,000.

- "Diagnóstico social de la comunidad gitana en España : Un análisis contrastado de la Encuesta del CIS a Hogares de Población Gitana 2007" (PDF). mscbs.gob.es. 2007.

Tabla 1. La comunidad gitana de España en el contexto de la población romaní de la Unión Europea. Población Romaní: 750.000 [...] Por 100 habitantes: 1,87% [...] se podrían llegar a barajar cifras [...] de 1.100.000 personas

- "Roma integration in Romania". European Commission – European Commission.

- 2011 census data, based on table 7 Population by ethnicity, gives a total of 621,573 Roma in Romania. This figure is disputed by other sources, because at the local level, many Roma declare a different ethnicity (mostly Romanian, but also Hungarian in Transylvania and Turkish in Dobruja). Many are not recorded at all, since they do not have ID cards . International sources give higher figures than the official census(UNDP's Regional Bureau for Europe Archived 7 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, World Bank, International Association for Official Statistics Archived 26 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine).

- "Rezultatele finale ale Recensământului din 2011 – Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune" (XLS) (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 5 July 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013. However, various organizations claim that there are 2 million Romanis in Romania. See

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Türkiye'deki Kürtlerin sayısı!" [The number of Kurds in Turkey!] (in Turkish). 6 June 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- "Türkiye'deki Çingene nüfusu tam bilinmiyor. 2, hatta 5 milyon gibi rakamlar dolaşıyor Çingenelerin arasında". Hurriyet (in Turkish). TR. 8 May 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- "Situation of Roma in France at crisis proportions". EurActiv Network. 7 December 2005. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

According to the report, the settled Gypsy population in France is officially estimated at around 500,000, although other estimates say that the actual figure is much closer to 1.2 million.

- Gorce, Bernard (22 July 2010). "Roms, gens du voyage, deux réalités différentes". La Croix. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

[MANUAL TRANS.] The ban prevents statistics on ethnicity to give a precise figure of French Roma, but we often quote the number 350,000. For travellers, the administration counted 160,000 circulation titles in 2006 issued to people aged 16 to 80 years. Among the travellers, some have chosen to buy a family plot where they dock their caravans around a local section (authorized since the Besson Act of 1990).

- Население по местоживеене, възраст и етническа група [Population by place of residence, age and ethnic group]. Bulgarian National Statistical Institute (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2015. Self declared

- "Roma Integration – 2014 Commission Assessment: Questions and Answers" (Press release). Brussels: European Commission. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2016. EU and Council of Europe estimates

- Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- János, Pénzes; Patrik, Tátrai; Zoltán, Pásztor István (2018). "A roma népesség területi megoszlásának változása Magyarországon az elmúlt évtizedekben" [Changes in the Spatial Distribution of the Roma Population in Hungary During the Last Decades] (PDF). Területi Statisztika (in Hungarian). 58 (1): 3–26. doi:10.15196/TS580101 (inactive 21 May 2020).

- Marsh, Hazel. "The Roma Gypsies of Colombia". latinolife.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- http://www.errc.org/roma-rights-journal/emerging-romani-voices-from-latin-america

- "Roma integration in the United Kingdom". European Commission – European Commission.

- "RME", Ethnologue

- Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији: Национална припадност [Census of population, households and apartments in 2011 in the Republic of Serbia: Ethnicity] (PDF) (in Serbian). State Statistical Service of the Republic of Serbia. 29 November 2012. p. 8. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "Serbia: Country Profile 2011–2012" (PDF). European Roma Rights Centre. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "Giornata Internazionale dei rom e sinti: presentato il Rapporto Annuale 2014 (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- "Premier Tsipras Hosts Roma Delegation for International Romani Day". greekreporter –place =. Nick Kampouris.

- "Greece NGO". Greek Helsinki Monitor. LV: Minelres.

- "Roma in Deutschland", Regionale Dynamik, Berlin-Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung

- "Roma integration in Slovakia". European Commission – European Commission.

- "Population and Housing Census. Resident population by nationality" (PDF). SK: Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2007.

- "Po deviatich rokoch spočítali Rómov, na Slovensku ich žije viac ako 400-tisíc". SME (in Slovak). SK: SITA. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Gypsy". Archived from the original on 15 May 2017.

- "The 2002-census reported 53,879 Roma and 3,843 'Egyptians'". Republic of Macedonia, State Statistical Office. Archived from the original on 21 June 2004. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "Sametingen. Information about minorities in Sweden", Minoritet (in Swedish), IMCMS

- Всеукраїнський перепис населення '2001: Розподіл населення за національністю та рідною мовою [Ukrainian Census, 2001: Distribution of population by nationality and mother tongue] (in Ukrainian). UA: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- Roma /Gypsies: A European Minority, Minority Rights Group International

- Kenrick, Donald (5 July 2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8108-6440-5.

- Hazel Marsh. "The Roma Gypsies of Latin America". www.latinolife.co.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "Poland – Gypsies". Country studies. US. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "POPULATION BY ETHNICITY – DETAILED CLASSIFICATION, 2011 CENSUS". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Emilio Godoy (12 October 2010). "Gypsies, or How to Be Invisible in Mexico". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- 2004 census

- "Suomen romanit - Finitiko romaseele" (PDF). Government of Finland. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1991 census

- https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/grupos-etnicos/presentacion-grupos-etnicos-poblacion-gitana-rrom-2019.pdf

- "Albanian census 2011". instat.gov.al. Archived from the original (XLS) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Republic of Belarus, 2009 Census: Population by Ethnicity and Native Language" (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Roma in Canada fact sheet" (PDF). home.cogeco.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007.

- Statistics Canada. "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). 12 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Gall, Timothy L, ed. (1998), Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life, 4. Europe, Cleveland, OH: Eastword, pp. 316, 318,

'Religion: An underlay of Hinduism with an overlay of either Christianity or Islam (host country religion)'; Roma religious beliefs are rooted in Hinduism. Roma believe in a universal balance, called kuntari... Despite a 1,000-year separation from India, Roma still practice 'shaktism', the worship of a god through his female consort...

- Hancock 2002, p. xx: 'While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Romani groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European'

- K. Meira Goldberg; Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum; Michelle Heffner Hayes (2015). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7864-9470-5. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India". New York Times.

- Kalaydjieva, Luba; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A; Angelicheva, Dora; de Knijff, Peter; Rosser, Zoe H; Hurles, Matthew; Underhill, Peter; Tournev, Ivailo; Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin (2011), "Patterns of inter- and intra-group genetic diversity in the Vlax Roma as revealed by Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA lineages" (PDF), European Journal of Human Genetics, 9 (2): 97–104, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200597, PMID 11313742, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2014

- Kenrick, Donald (5 July 2007). Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies (Romanies) (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. xxxvii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6440-5.

The Gypsies, or Romanies, are an ethnic group that arrived in Europe around the 14th century. Scholars argue about when and how they left India, but it is generally accepted that they did emigrate from northern India some time between the 6th and 11th centuries, then crossed the Middle East and came into Europe.

- "What is Domari?". University of Manchester. Romani Linguistics and Romani Language Projects. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- Randall, Kay. "What's in a Name? Professor take on roles of Romani activist and spokesperson to improve plight of their ethnic group". Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "The Gypsy Lore Society" (Journal).

- "60 Vintage Photos From Forgotten Moments In History: A young Romani couple from the 1890s". History Daily. 3 April 2019.

- Corrêa Teixeira, Rodrigo. "A história dos ciganos no Brasil" (PDF). Dhnet.org.br. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Sutherland 1986.