Apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (Malus domestica). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus Malus. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, Malus sieversii, is still found today. Apples have been grown for thousands of years in Asia and Europe and were brought to North America by European colonists. Apples have religious and mythological significance in many cultures, including Norse, Greek and European Christian tradition.

| Apple | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruit of the Honeycrisp cultivar | |

| |

| Flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica |

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica Borkh., 1803 | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Apple trees are large if grown from seed. Generally, apple cultivars are propagated by grafting onto rootstocks, which control the size of the resulting tree. There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples, resulting in a range of desired characteristics. Different cultivars are bred for various tastes and use, including cooking, eating raw and cider production. Trees and fruit are prone to a number of fungal, bacterial and pest problems, which can be controlled by a number of organic and non-organic means. In 2010, the fruit's genome was sequenced as part of research on disease control and selective breeding in apple production.

Worldwide production of apples in 2018 was 86 million tonnes, with China accounting for nearly half of the total.[3]

Etymology

The word "apple", formerly spelled æppel in Old English, is derived from the Proto-Germanic root *ap(a)laz, which could also mean fruit in general. This is ultimately derived from Proto-Indo-European *ab(e)l-, but the precise original meaning and the relationship between both words is uncertain.

As late as the 17th century, the word also functioned as a generic term for all fruit other than berries but including nuts—such as the 14th century Middle English word appel of paradis, meaning a banana.[4] This use is analogous to the French language use of pomme.

Description

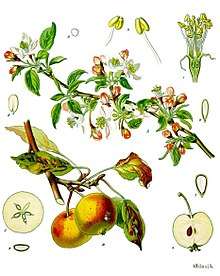

The apple is a deciduous tree, generally standing 2 to 4.5 m (6 to 15 ft) tall in cultivation and up to 9 m (30 ft) in the wild. When cultivated, the size, shape and branch density are determined by rootstock selection and trimming method. The leaves are alternately arranged dark green-colored simple ovals with serrated margins and slightly downy undersides.[5]

Blossoms are produced in spring simultaneously with the budding of the leaves and are produced on spurs and some long shoots. The 3 to 4 cm (1 to 1 1⁄2 in) flowers are white with a pink tinge that gradually fades, five petaled, with an inflorescence consisting of a cyme with 4–6 flowers. The central flower of the inflorescence is called the "king bloom"; it opens first and can develop a larger fruit.[5][6]

The fruit matures in late summer or autumn, and cultivars exist in a wide range of sizes. Commercial growers aim to produce an apple that is 7 to 8.5 cm (2 3⁄4 to 3 1⁄4 in) in diameter, due to market preference. Some consumers, especially those in Japan, prefer a larger apple, while apples below 5.5 cm (2 1⁄4 in) are generally used for making juice and have little fresh market value. The skin of ripe apples is generally red, yellow, green, pink, or russetted, though many bi- or tri-colored cultivars may be found.[7] The skin may also be wholly or partly russeted i.e. rough and brown. The skin is covered in a protective layer of epicuticular wax.[8] The exocarp (flesh) is generally pale yellowish-white,[7] though pink or yellow exocarps also occur.

Wild ancestors

The original wild ancestor of Malus domestica was Malus sieversii, found growing wild in the mountains of Central Asia in southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Xinjiang, China.[5][9] Cultivation of the species, most likely beginning on the forested flanks of the Tian Shan mountains, progressed over a long period of time and permitted secondary introgression of genes from other species into the open-pollinated seeds. Significant exchange with Malus sylvestris, the crabapple, resulted in current populations of apples being more related to crabapples than to the more morphologically similar progenitor Malus sieversii. In strains without recent admixture the contribution of the latter predominates.[10][11][12]

Genome

In 2010, an Italian-led consortium announced they had sequenced the complete genome of the apple in collaboration with horticultural genomicists at Washington State University,[13] using 'Golden Delicious'.[14] It had about 57,000 genes, the highest number of any plant genome studied to date[15] and more genes than the human genome (about 30,000).[16] This new understanding of the apple genome will help scientists identify genes and gene variants that contribute to resistance to disease and drought, and other desirable characteristics. Understanding the genes behind these characteristics will help scientists perform more knowledgeable selective breeding. The genome sequence also provided proof that Malus sieversii was the wild ancestor of the domestic apple—an issue that had been long-debated in the scientific community.[13]

History

Malus sieversii is recognized as a major progenitor species to the cultivated apple, and is morphologically similar. Due to the genetic variability in Central Asia, this region is generally considered the center of origin for apples.[17] The apple is thought to have been domesticated 4000-10000 years ago in the Tian Shan Mountains, and then to have travelled along the Silk Road to Europe, with hybridization and introgression of wild crabapples from Siberia (M. baccata), Caucasus (M. orientalis), and Europe (M. sylvestris). Only the M. sieversii trees growing on the western side of Tian Shan Mountains contributed genetically to the domesticated apple, not the isolated population on the eastern side.[18]

Chinese soft apples, such as M. asiatica and M. prunifolia, have been cultivated as dessert apples for more than 2000 years in China. These are thought to be hybrids between M. baccata and M. sieversii in Kazakhstan.[18]

Among the traits selected for by human growers are size, fruit acidity, color, firmness, and soluble sugar. Unusually for domesticated fruits, the wild M. sieversii origin is only slightly smaller than the modern domesticated apple.[18]

At the Sammardenchia-Cueis site near Udine in Northeastern Italy, seeds from some form of apples have been found in material carbon dated to around 4000 BCE.[19] Genetic analysis has not yet been successfully used to determine whether such ancient apples were wild Malus Sylvestris or Malus Domesticus containing Malus sieversii ancestry.[20] It is generally also hard to distinguish in the archeological record between foraged wild apples and apple plantations.

There is indirect evidence of apple cultivation in the third millennium BCE in the Middle East. There was substantial apple production in the European classical antiquity, and grafting was certainly known then.[20] Grafting is an essential part of modern domesticated apple production, to be able to propagate the best cultivars; it is unclear when apple tree grafting was invented.[20]

Winter apples, picked in late autumn and stored just above freezing, have been an important food in Asia and Europe for millennia.[21] Of the many Old World plants that the Spanish introduced to Chiloé Archipelago in the 16th century, apple trees became particularly well adapted.[22] Apples were introduced to North America by colonists in the 17th century,[5] and the first apple orchard on the North American continent was planted in Boston by Reverend William Blaxton in 1625.[23] The only apples native to North America are crab apples, which were once called "common apples".[24] Apple cultivars brought as seed from Europe were spread along Native American trade routes, as well as being cultivated on colonial farms. An 1845 United States apples nursery catalogue sold 350 of the "best" cultivars, showing the proliferation of new North American cultivars by the early 19th century.[24] In the 20th century, irrigation projects in Eastern Washington began and allowed the development of the multibillion-dollar fruit industry, of which the apple is the leading product.[5]

Until the 20th century, farmers stored apples in frostproof cellars during the winter for their own use or for sale. Improved transportation of fresh apples by train and road replaced the necessity for storage.[25][26] Controlled atmosphere facilities are used to keep apples fresh year-round. Controlled atmosphere facilities use high humidity, low oxygen, and controlled carbon dioxide levels to maintain fruit freshness. They were first used in the United States in the 1960s.[27]

Society and culture

Germanic paganism

In Norse mythology, the goddess Iðunn is portrayed in the Prose Edda (written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson) as providing apples to the gods that give them eternal youthfulness. English scholar H. R. Ellis Davidson links apples to religious practices in Germanic paganism, from which Norse paganism developed. She points out that buckets of apples were found in the Oseberg ship burial site in Norway, that fruit and nuts (Iðunn having been described as being transformed into a nut in Skáldskaparmál) have been found in the early graves of the Germanic peoples in England and elsewhere on the continent of Europe, which may have had a symbolic meaning, and that nuts are still a recognized symbol of fertility in southwest England.[28]

Davidson notes a connection between apples and the Vanir, a tribe of gods associated with fertility in Norse mythology, citing an instance of eleven "golden apples" being given to woo the beautiful Gerðr by Skírnir, who was acting as messenger for the major Vanir god Freyr in stanzas 19 and 20 of Skírnismál. Davidson also notes a further connection between fertility and apples in Norse mythology in chapter 2 of the Völsunga saga when the major goddess Frigg sends King Rerir an apple after he prays to Odin for a child, Frigg's messenger (in the guise of a crow) drops the apple in his lap as he sits atop a mound.[29] Rerir's wife's consumption of the apple results in a six-year pregnancy and the Caesarean section birth of their son—the hero Völsung.[30]

Further, Davidson points out the "strange" phrase "Apples of Hel" used in an 11th-century poem by the skald Thorbiorn Brúnarson. She states this may imply that the apple was thought of by Brúnarson as the food of the dead. Further, Davidson notes that the potentially Germanic goddess Nehalennia is sometimes depicted with apples and that parallels exist in early Irish stories. Davidson asserts that while cultivation of the apple in Northern Europe extends back to at least the time of the Roman Empire and came to Europe from the Near East, the native varieties of apple trees growing in Northern Europe are small and bitter. Davidson concludes that in the figure of Iðunn "we must have a dim reflection of an old symbol: that of the guardian goddess of the life-giving fruit of the other world."[28]

Greek mythology

Apples appear in many religious traditions, often as a mystical or forbidden fruit. One of the problems identifying apples in religion, mythology and folktales is that the word "apple" was used as a generic term for all (foreign) fruit, other than berries, including nuts, as late as the 17th century.[31] For instance, in Greek mythology, the Greek hero Heracles, as a part of his Twelve Labours, was required to travel to the Garden of the Hesperides and pick the golden apples off the Tree of Life growing at its center.[32][33][34]

The Greek goddess of discord, Eris, became disgruntled after she was excluded from the wedding of Peleus and Thetis.[35] In retaliation, she tossed a golden apple inscribed Καλλίστη (Kalliste, sometimes transliterated Kallisti, "For the most beautiful one"), into the wedding party. Three goddesses claimed the apple: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Paris of Troy was appointed to select the recipient. After being bribed by both Hera and Athena, Aphrodite tempted him with the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. He awarded the apple to Aphrodite, thus indirectly causing the Trojan War.[36]

The apple was thus considered, in ancient Greece, sacred to Aphrodite. To throw an apple at someone was to symbolically declare one's love; and similarly, to catch it was to symbolically show one's acceptance of that love. An epigram claiming authorship by Plato states:[37]

I throw the apple at you, and if you are willing to love me, take it and share your girlhood with me; but if your thoughts are what I pray they are not, even then take it, and consider how short-lived is beauty.

— Plato, Epigram VII

Atalanta, also of Greek mythology, raced all her suitors in an attempt to avoid marriage. She outran all but Hippomenes (also known as Melanion, a name possibly derived from melon the Greek word for both "apple" and fruit in general),[33] who defeated her by cunning, not speed. Hippomenes knew that he could not win in a fair race, so he used three golden apples (gifts of Aphrodite, the goddess of love) to distract Atalanta. It took all three apples and all of his speed, but Hippomenes was finally successful, winning the race and Atalanta's hand.[32]

Christian art

_2.jpg)

Though the forbidden fruit of Eden in the Book of Genesis is not identified, popular Christian tradition has held that it was an apple that Eve coaxed Adam to share with her.[38] The origin of the popular identification with a fruit unknown in the Middle East in biblical times is found in confusion between the Latin words mālum (an apple) and mălum (an evil), each of which is normally written malum.[39] The tree of the forbidden fruit is called "the tree of the knowledge of good and evil" in Genesis 2:17, and the Latin for "good and evil" is bonum et malum.[40]

Renaissance painters may also have been influenced by the story of the golden apples in the Garden of Hesperides. As a result, in the story of Adam and Eve, the apple became a symbol for knowledge, immortality, temptation, the fall of man into sin, and sin itself. The larynx in the human throat has been called the "Adam's apple" because of a notion that it was caused by the forbidden fruit remaining in the throat of Adam.[38] The apple as symbol of sexual seduction has been used to imply human sexuality, possibly in an ironic vein.[38]

Proverb

The proverb, "An apple a day keeps the doctor away", addressing the supposed health benefits of the fruit, has been traced to 19th-century Wales, where the original phrase was "Eat an apple on going to bed, and you'll keep the doctor from earning his bread".[41] In the 19th century and early 20th, the phrase evolved to "an apple a day, no doctor to pay" and "an apple a day sends the doctor away"; the phrasing now commonly used was first recorded in 1922.[42] Despite the proverb, there is no evidence that eating an apple daily has any significant health effects.[43]

Cultivars

There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples.[44] Cultivars vary in their yield and the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the same rootstock.[45] Different cultivars are available for temperate and subtropical climates. The UK's National Fruit Collection, which is the responsibility of the Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, includes a collection of over 2,000 cultivars of apple tree in Kent.[46] The University of Reading, which is responsible for developing the UK national collection database, provides access to search the national collection. The University of Reading's work is part of the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources of which there are 38 countries participating in the Malus/Pyrus work group.[47]

The UK's national fruit collection database contains much information on the characteristics and origin of many apples, including alternative names for what is essentially the same "genetic" apple cultivar. Most of these cultivars are bred for eating fresh (dessert apples), though some are cultivated specifically for cooking (cooking apples) or producing cider. Cider apples are typically too tart and astringent to eat fresh, but they give the beverage a rich flavor that dessert apples cannot.[48]

Commercially popular apple cultivars are soft but crisp. Other desirable qualities in modern commercial apple breeding are a colorful skin, absence of russeting, ease of shipping, lengthy storage ability, high yields, disease resistance, common apple shape, and developed flavor.[45] Modern apples are generally sweeter than older cultivars, as popular tastes in apples have varied over time. Most North Americans and Europeans favor sweet, subacid apples, but tart apples have a strong minority following.[49] Extremely sweet apples with barely any acid flavor are popular in Asia,[49] especially the Indian Subcontinent.[48]

Old cultivars are often oddly shaped, russeted, and grow in a variety of textures and colors. Some find them to have better flavor than modern cultivars,[50] but they may have other problems that make them commercially unviable—low yield, disease susceptibility, poor tolerance for storage or transport, or just being the "wrong" size. A few old cultivars are still produced on a large scale, but many have been preserved by home gardeners and farmers that sell directly to local markets. Many unusual and locally important cultivars with their own unique taste and appearance exist; apple conservation campaigns have sprung up around the world to preserve such local cultivars from extinction. In the United Kingdom, old cultivars such as 'Cox's Orange Pippin' and 'Egremont Russet' are still commercially important even though by modern standards they are low yielding and susceptible to disease.[5]

Cultivation

Breeding

Many apples grow readily from seeds. However, more than with most perennial fruits, apples must be propagated asexually to obtain the sweetness and other desirable characteristics of the parent. This is because seedling apples are an example of "extreme heterozygotes", in that rather than inheriting genes from their parents to create a new apple with parental characteristics, they are instead significantly different from their parents, perhaps to compete with the many pests.[51] Triploid cultivars have an additional reproductive barrier in that 3 sets of chromosomes cannot be divided evenly during meiosis, yielding unequal segregation of the chromosomes (aneuploids). Even in the case when a triploid plant can produce a seed (apples are an example), it occurs infrequently, and seedlings rarely survive.[52]

Because apples do not breed true when planted as seeds, although cuttings can take root and breed true, and may live for a century, grafting is usually used. The rootstock used for the bottom of the graft can be selected to produce trees of a large variety of sizes, as well as changing the winter hardiness, insect and disease resistance, and soil preference of the resulting tree. Dwarf rootstocks can be used to produce very small trees (less than 3.0 m or 10 ft high at maturity), which bear fruit many years earlier in their life cycle than full size trees, and are easier to harvest.[53] Dwarf rootstocks for apple trees can be traced as far back as 300 BCE, to the area of Persia and Asia Minor. Alexander the Great sent samples of dwarf apple trees to Aristotle's Lyceum. Dwarf rootstocks became common by the 15th century and later went through several cycles of popularity and decline throughout the world.[54] The majority of the rootstocks used today to control size in apples were developed in England in the early 1900s. The East Malling Research Station conducted extensive research into rootstocks, and today their rootstocks are given an "M" prefix to designate their origin. Rootstocks marked with an "MM" prefix are Malling-series cultivars later crossed with trees of 'Northern Spy' in Merton, England.[55]

Most new apple cultivars originate as seedlings, which either arise by chance or are bred by deliberately crossing cultivars with promising characteristics.[56] The words "seedling", "pippin", and "kernel" in the name of an apple cultivar suggest that it originated as a seedling. Apples can also form bud sports (mutations on a single branch). Some bud sports turn out to be improved strains of the parent cultivar. Some differ sufficiently from the parent tree to be considered new cultivars.[57]

Since the 1930s, the Excelsior Experiment Station at the University of Minnesota has introduced a steady progression of important apples that are widely grown, both commercially and by local orchardists, throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin. Its most important contributions have included 'Haralson' (which is the most widely cultivated apple in Minnesota), 'Wealthy', 'Honeygold', and 'Honeycrisp'.

Apples have been acclimatized in Ecuador at very high altitudes, where they can often, with the needed factors, provide crops twice per year because of constant temperate conditions year-round.[58]

Pollination

Apples are self-incompatible; they must cross-pollinate to develop fruit. During the flowering each season, apple growers often utilize pollinators to carry pollen. Honey bees are most commonly used. Orchard mason bees are also used as supplemental pollinators in commercial orchards. Bumblebee queens are sometimes present in orchards, but not usually in sufficient number to be significant pollinators.[57][59]

There are four to seven pollination groups in apples, depending on climate:

- Group A – Early flowering, 1 to 3 May in England ('Gravenstein', 'Red Astrachan')

- Group B – 4 to 7 May ('Idared', 'McIntosh')

- Group C – Mid-season flowering, 8 to 11 May ('Granny Smith', 'Cox's Orange Pippin')

- Group D – Mid/late season flowering, 12 to 15 May ('Golden Delicious', 'Calville blanc d'hiver')

- Group E – Late flowering, 16 to 18 May ('Braeburn', 'Reinette d'Orléans')

- Group F – 19 to 23 May ('Suntan')

- Group H – 24 to 28 May ('Court-Pendu Gris' – also called Court-Pendu plat)

One cultivar can be pollinated by a compatible cultivar from the same group or close (A with A, or A with B, but not A with C or D).[60]

Cultivars are sometimes classified by the day of peak bloom in the average 30-day blossom period, with pollenizers selected from cultivars within a 6-day overlap period.

Maturation and harvest

Cultivars vary in their yield and the ultimate size of the tree, even when grown on the same rootstock. Some cultivars, if left unpruned, grow very large—letting them bear more fruit, but making harvesting more difficult. Depending on tree density (number of trees planted per unit surface area), mature trees typically bear 40–200 kg (90–440 lb) of apples each year, though productivity can be close to zero in poor years. Apples are harvested using three-point ladders that are designed to fit amongst the branches. Trees grafted on dwarfing rootstocks bear about 10–80 kg (20–180 lb) of fruit per year.[57]

Farms with apple orchards open them to the public so consumers can pick their own apples.[61]

Crops ripen at different times of the year according to the cultivar. Cultivar that yield their crop in the summer include 'Gala', 'Golden Supreme', 'McIntosh', 'Transparent', 'Primate', 'Sweet Bough', and 'Duchess'; fall producers include 'Fuji', 'Jonagold', 'Golden Delicious', 'Red Delicious', 'Chenango', 'Gravenstein', 'Wealthy', 'McIntosh', 'Snow', and 'Blenheim'; winter producers include 'Winesap', 'Granny Smith', 'King', 'Wagener', 'Swayzie', 'Greening', and 'Tolman Sweet'.[24]

Storage

Commercially, apples can be stored for some months in controlled atmosphere chambers to delay ethylene-induced ripening. Apples are commonly stored in chambers with higher concentrations of carbon dioxide and high air filtration. This prevents ethylene concentrations from rising to higher amounts and preventing ripening from occurring too quickly.

For home storage, most cultivars of apple can be held for approximately two weeks when kept at the coolest part of the refrigerator (i.e. below 5 °C). Some can be stored up to a year without significant degradation.[62] Some varieties of apples (e.g. 'Granny Smith' and 'Fuji') have more than three times the storage life of others.[63]

Non-organic apples may be sprayed with 1-methylcyclopropene blocking the apples' ethylene receptors, temporarily preventing them from ripening.[64]

Pests and diseases

Apple trees are susceptible to a number of fungal and bacterial diseases and insect pests. Many commercial orchards pursue a program of chemical sprays to maintain high fruit quality, tree health, and high yields. These prohibit the use of synthetic pesticides, though some older pesticides are allowed. Organic methods include, for instance, introducing its natural predator to reduce the population of a particular pest.

A wide range of pests and diseases can affect the plant. Three of the more common diseases or pests are mildew, aphids, and apple scab.

- Mildew is characterized by light grey powdery patches appearing on the leaves, shoots and flowers, normally in spring. The flowers turn a creamy yellow color and do not develop correctly. This can be treated similarly to Botrytis—eliminating the conditions that caused the disease and burning the infected plants are among recommended actions.[65]

- Aphids are a small insect. Five species of aphids commonly attack apples: apple grain aphid, rosy apple aphid, apple aphid, spirea aphid, and the woolly apple aphid. The aphid species can be identified by color, time of year, and by differences in the cornicles (small paired projections from their rear).[65] Aphids feed on foliage using needle-like mouth parts to suck out plant juices. When present in high numbers, certain species reduce tree growth and vigor.[66]

- Apple scab: Apple scab causes leaves to develop olive-brown spots with a velvety texture that later turn brown and become cork-like in texture. The disease also affects the fruit, which also develops similar brown spots with velvety or cork-like textures. Apple scab is spread through fungus growing in old apple leaves on the ground and spreads during warm spring weather to infect the new year's growth.[67]

Among the most serious disease problems are a bacterial disease called fireblight, and two fungal diseases: Gymnosporangium rust and black spot.[66] Other pests that affect apple trees include Codling moths and apple maggots. Young apple trees are also prone to mammal pests like mice and deer, which feed on the soft bark of the trees, especially in winter.[67] The larvae of the apple clearwing moth (red-belted clearwing) burrow through the bark and into the phloem of apple trees, potentially causing significant damage.[68]

Production

| Apple production – 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (millions of tonnes) |

| 39.2 | |

| 4.7 | |

| 4.0 | |

| 3.6 | |

| 2.5 | |

| 2.4 | |

| 2.3 | |

| World | 86.1 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[3] | |

World production of apples in 2018 was 86 million tonnes, with China producing 46% of the total (table).[3] Secondary producers were the United States and Poland.[3]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 218 kJ (52 kcal) |

13.81 g | |

| Sugars | 10.39 |

| Dietary fiber | 2.4 g |

0.17 g | |

0.26 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 3 μg0% 27 μg29 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 1% 0.017 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.026 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 1% 0.091 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 1% 0.061 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 3% 0.041 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 1% 3 μg |

| Vitamin C | 6% 4.6 mg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.18 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.2 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 6 mg |

| Iron | 1% 0.12 mg |

| Magnesium | 1% 5 mg |

| Manganese | 2% 0.035 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 11 mg |

| Potassium | 2% 107 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1 mg |

| Zinc | 0% 0.04 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 85.56 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

A raw apple is 86% water and 14% carbohydrates, with negligible content of fat and protein (table). A reference serving of a raw apple with skin weighing 100 grams provides 52 calories and a moderate content of dietary fiber.[69] Otherwise, there is low content of all micronutrients (table).

Uses

All parts of the fruit, including the skin, except for the seeds, are suitable for human consumption. The core, from stem to bottom, containing the seeds, is usually not eaten and is discarded.

Apples can be consumed various ways: juice, raw in salads, baked in pies, cooked into sauces and spreads like apple butter, and other baked dishes.[70]

Several techniques are used to preserve apples and apple products. Apples can be canned, dried or frozen.[70] Canned or frozen apples are eventually baked into pies or other cooked dishes. Apple juice or cider is also bottled. Apple juice is often concentrated and frozen.

Popular uses

Apples are often eaten raw. Cultivars bred for raw consumption are termed dessert or table apples.

- In the UK, a toffee apple is a traditional confection made by coating an apple in hot toffee and allowing it to cool. Similar treats in the U.S. are candy apples (coated in a hard shell of crystallized sugar syrup) and caramel apples (coated with cooled caramel).

- Apples are eaten with honey at the Jewish New Year of Rosh Hashanah to symbolize a sweet new year.[61]

Apples are an important ingredient in many desserts, such as apple pie, apple crumble, apple crisp and apple cake. When cooked, some apple cultivars easily form a puree known as apple sauce. Apples are also made into apple butter and apple jelly. They are often baked or stewed and are also (cooked) in some meat dishes. Dried apples can be eaten or reconstituted (soaked in water, alcohol or some other liquid).

Apples are milled or pressed to produce apple juice, which may be drunk unfiltered (called apple cider in North America), or filtered. Filtered juice is often concentrated and frozen, then reconstituted later and consumed. Apple juice can be fermented to make cider (called hard cider in North America), ciderkin, and vinegar. Through distillation, various alcoholic beverages can be produced, such as applejack, Calvados, and apfelwein.[71]

Organic production

Organic apples are commonly produced in the United States.[72] Due to infestations by key insects and diseases, organic production is difficult in Europe.[73] The use of pesticides containing chemicals, such as sulfur, copper, microorganisms, viruses, clay powders, or plant extracts (pyrethrum, neem) has been approved by the EU Organic Standing Committee to improve organic yield and quality.[73] A light coating of kaolin, which forms a physical barrier to some pests, also may help prevent apple sun scalding.[57]

Phytochemicals

Apple skins and seeds contain various phytochemicals, particularly polyphenols which are under preliminary research for their potential health effects.[74]

Non-browning apples

The enzyme, polyphenol oxidase, causes browning in sliced or bruised apples, by catalyzing the oxidation of phenolic compounds to o-quinones, a browning factor.[75] Browning reduces apple taste, color, and food value. Arctic Apples, a non-browning group of apples introduced to the United States market in 2019, have been genetically modified to silence the expression of polyphenol oxidase, thereby delaying a browning effect and improving apple eating quality.[76][77] The US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, and Canadian Food Inspection Agency in 2017, determined that Arctic apples are as safe and nutritious as conventional apples.[78][79]

Other products

Apple seed oil is obtained by pressing apple seeds for manufacturing cosmetics.[80]

Research

Preliminary research is investigating whether apple consumption may affect the risk of some types of cancer.[74][81]

Allergy

One form of apple allergy, often found in northern Europe, is called birch-apple syndrome and is found in people who are also allergic to birch pollen.[82] Allergic reactions are triggered by a protein in apples that is similar to birch pollen, and people affected by this protein can also develop allergies to other fruits, nuts, and vegetables. Reactions, which entail oral allergy syndrome (OAS), generally involve itching and inflammation of the mouth and throat,[82] but in rare cases can also include life-threatening anaphylaxis.[83] This reaction only occurs when raw fruit is consumed—the allergen is neutralized in the cooking process. The variety of apple, maturity and storage conditions can change the amount of allergen present in individual fruits. Long storage times can increase the amount of proteins that cause birch-apple syndrome.[82]

In other areas, such as the Mediterranean, some individuals have adverse reactions to apples because of their similarity to peaches.[82] This form of apple allergy also includes OAS, but often has more severe symptoms, such as vomiting, abdominal pain and urticaria, and can be life-threatening. Individuals with this form of allergy can also develop reactions to other fruits and nuts. Cooking does not break down the protein causing this particular reaction, so affected individuals cannot eat raw or cooked apples. Freshly harvested, over-ripe fruits tend to have the highest levels of the protein that causes this reaction.[82]

Breeding efforts have yet to produce a hypoallergenic fruit suitable for either of the two forms of apple allergy.[82]

Toxicity of seeds

Apple seeds contain small amounts of amygdalin, a sugar and cyanide compound known as a cyanogenic glycoside. Ingesting small amounts of apple seeds causes no ill effects, but consumption of extremely large doses can cause adverse reactions. It may take several hours before the poison takes effect, as cyanogenic glycosides must be hydrolyzed before the cyanide ion is released.[84] The United States National Library of Medicine's Hazardous Substances Data Bank records no cases of amygdalin poisoning from consuming apple seeds.[85]

See also

- Apple chip

- Applecrab, apple–crabapple hybrids for eating

- Cooking apple

- Johnny Appleseed

- List of apple cultivars

- List of apple dishes

- Rootstock

- Welsh apples

References

- Dickson, Elizabeth E. (2014). "Malus pumila". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 9. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Karen L. Wilson (2017), "Report of the Nomenclature Committee for Vascular Plants: 66: (1933). To conserve Malus domestica Borkh. against M. pumila Miller", Taxon, 66 (3): 742–744, doi:10.12705/663.15

- "Apple production in 2018; Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity". FAOSTAT, UN Food & Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division. 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Origin and meaning of "apple" by Online Etymology Dictionary". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Origin, History of cultivation". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- "Apple". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Jules Janick; James N. Cummins; Susan K. Brown; Minou Hemmat (1996). "Chapter 1: Apples" (PDF). In Jules Janick; James N. Moore (eds.). Fruit Breeding, Volume I: Tree and Tropical Fruits. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-471-31014-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2013.

- "Natural Waxes on Fruits". Postharvest.tfrec.wsu.edu. 29 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Lauri, Pierre-éric; Karen Maguylo; Catherine Trottier (2006). "Architecture and size relations: an essay on the apple (Malus x domestica, Rosaceae) tree". American Journal of Botany. 93 (3): 357–368. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.3.357. PMID 21646196.

- Amandine Cornille; et al. (2012). Mauricio, Rodney (ed.). "New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties". PLOS Genetics. 8 (5): e1002703. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002703. PMC 3349737. PMID 22589740.

- Sam Kean (17 May 2012). "ScienceShot: The Secret History of the Domesticated Apple". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016.

- Coart, E.; Van Glabeke, S.; De Loose, M.; Larsen, A.S.; Roldán-Ruiz, I. (2006). "Chloroplast diversity in the genus Malus: new insights into the relationship between the European wild apple (Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill.) and the domesticated apple (Malus domestica Borkh.)". Mol. Ecol. 15 (8): 2171–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2006.02924.x. PMID 16780433.

- Clark Brian (29 August 2010). "Apple Cup Rivals Contribute to Apple Genome Sequencing". Cahnrsnews.wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Velasco, R; Zharkikh, A; Affourtit, J; et al. (October 2010). "The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.)". Nature Genetics. 42 (10): 833–839. doi:10.1038/ng.654. PMID 20802477.

- An Italian-led international research consortium decodes the apple genome Archived 5 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine AlphaGallileo 29 August 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- The Science Behind the Human Genome Project Archived 2 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Human Genome Project Information, US Department of Energy, 26 March 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- Christopher M. Richards & Gayle M. Volk & Ann A. Reilley & Adam D. Henk & Dale R. Lockwood & Patrick A. Reeves & Philip L. Forsline (2009), "Genetic diversity and population structure in Malus sieversii, a wild progenitor species of domesticated apple", Tree Genetics & Genomes, 5 (2): 339–347, doi:10.1007/s11295-008-0190-9CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Duan, Naibin; Bai, Yang; Sun, Honghe; Wang, Nan; Ma, Yumin; Li, Mingjun; Wang, Xin; Jiao, Chen; Legall, Noah; Mao, Linyong; Wan, Sibao; Wang, Kun; He, Tianming; Feng, Shouqian; Zhang, Zongying; Mao, Zhiquan; Shen, Xiang; Chen, Xiaoliu; Jiang, Yuanmao; Wu, Shujing; Yin, Chengmiao; Ge, Shunfeng; Yang, Long; Jiang, Shenghui; Xu, Haifeng; Liu, Jingxuan; Wang, Deyun; Qu, Changzhi; Wang, Yicheng; et al. (2017), "Genome re-sequencing reveals the history of apple and supports a two-stage model for fruit enlargement", Nature Communications, 8 (1): 249, doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00336-7, PMC 5557836, PMID 28811498

- Sue Colledge, James Conolly (16 June 2016). "The Origins and Spread of Domestic Plants in Southwest Asia and Europe". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Angela Schlumbauma, Sabine van Glabeke, Isabel Roldan-Ruiz (2012). "Towards the onset of fruit tree growing north of the Alps: Ancient DNA from waterlogged apple (Malus sp.) seed fragments". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 194: 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.03.004. PMID 21501956.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "An apple a day keeps the doctor away". Vegetarians in Paradise. Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- Torrejón, Fernando; Cisternas, Marco; Araneda, Alberto (2004). "Efectos ambientales de la colonización española desde el río Maullín al archipiélago de Chiloé, sur de Chile" [Environmental effects of the spanish colonization from de Maullín river to the Chiloé archipelago, southern Chile]. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (in Spanish). 77 (4): 661–677. doi:10.4067/s0716-078x2004000400009.

- Smith, Archibald William (1997). A Gardener's Handbook of Plant Names: Their Meanings and Origins. Dover Publications. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-486-29715-6.

- Lawrence, James (1980). The Harrowsmith Reader, Volume II. Camden House Publishing Ltd. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-920656-10-5.

- James M. Van Valen (2010). History of Bergen county, New Jersey. Nabu Press. p. 744. ISBN 978-1-177-72589-7.

- Brox, Jane (2000). Five Thousand Days Like This One: An American Family History. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2107-1.

- "Controlled Atmospheric Storage (CA)". Washington Apple Commission. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965) Gods And Myths of Northern Europe, page 165 to 166. ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965) Gods And Myths of Northern Europe, page 165 to 166. Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1998) Roles of the Northern Goddess, page 146 to 147. Routledge ISBN 0-415-13610-5

- Sauer, Jonathan D. (1993). Historical Geography of Crop Plants: A Select Roster. CRC Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8493-8901-6.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1968). Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-15-683800-9.

- Ruck, Carl; Blaise Daniel Staples (2001). The Apples of Apollo, Pagan and Christian Mysteries of the Eucharist. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-0-89089-924-3.

- Heinrich, Clark (2002). Magic Mushrooms in Religion and Alchemy. Rochester: Park Street Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-0-89281-997-3.

- Hyginus. "92". Fabulae. Theoi Project. Translated by Mary Grant. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Lucian. "The Judgement of Paris". Dialogues of the Gods. Theoi Project. Translated by H. W. & F. G. Fowler. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Edmonds, J.M. (1997). "Epigrams". In Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S. (eds.). Plato: Complete Works. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co. p. 1744. ISBN 9780872203495. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Macrone, Michael; Tom Lulevitch (1998). Brush up your Bible!. Tom Lulevitch. Random House Value. ISBN 978-0-517-20189-3. OCLC 38270894.

- Kissling, Paul J (2004). Genesis. 1. College Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-89900875-2. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Hendel, Ronald (2012). The Book of Genesis: A Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-69114012-4. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "An Apple a Day: Old-Fashioned Proverbs and Why They Still Work", by Caroline Taggart; published 2009 by Michael O'Mara Books

- Pollan, Michael (2001). The Botany of Desire: a Plant's-eye View of the World. Random House. p. 22, cf. p. 9 & 50. ISBN 978-0375501296. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Davis, Matthew A.; Bynum, Julie P. W.; Sirovich, Brenda E. (1 May 2015). "Association between apple consumption and physician visits". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (5): 777–83. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5466. PMC 4420713. PMID 25822137.

- Elzebroek, A.T.G.; Wind, K. (2008). Guide to Cultivated Plants. Wallingford: CAB International. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-84593-356-2.

- "Apple – Malus domestica". Natural England. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- "National Fruit Collection". Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "ECPGR Malus/Pyrus Working Group Members". Ecpgr.cgiar.org. 22 July 2002. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Sue Tarjan (Fall 2006). "Autumn Apple Musings" (PDF). News & Notes of the UCSC Farm & Garden, Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- "World apple situation". Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- Weaver, Sue (June–July 2003). "Crops & Gardening – Apples of Antiquity". Hobby Farms Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- John Lloyd and John Mitchinson (2006). QI: The Complete First Series – QI Factoids (DVD). 2 entertain.

- Ranney, Thomas G. "Polyploidy: From Evolution to Landscape Plant Improvement". Proceedings of the 11th Metropolitan Tree Improvement Alliance (METRIA) Conference. 11th Metropolitan Tree Improvement Alliance (METRIA) Conference held in Gresham, Oregon, August 23–24, 2000. METRIA (NCSU.edu). METRIA. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- William G. Lord; Amy Ouellette (February 2010). "Dwarf Rootstocks for Apple Trees in the Home Garden" (PDF). University of New Hampshire. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Esmaeil Fallahi; W. Michael Colt; Bahar Fallahi; Ik-Jo Chun (January–March 2002). "The Importance of Apple Rootstocks on Tree Growth, Yield, Fruit Quality, Leaf Nutrition, and Photosynthesis with an Emphasis on 'Fuji'" (PDF). Hort Technology. 12 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 February 2014.

- ML Parker (September 1993). "Apple Rootstocks and Tree Spacing". North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Ferree, David Curtis; Ian J. Warrington (1999). Apples: Botany, Production and Uses. CABI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85199-357-7. OCLC 182530169.

- Bob Polomski; Greg Reighard. "Apple". Clemson University. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- Barahona, M. (1992). "Adaptation of Apple Varieties in Ecuador". Acta Hort. 310 (310): 139–142. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1992.310.17.

- Adamson, Nancy Lee. An Assessment of Non-Apis Bees as Fruit and Vegetable Crop Pollinators in Southwest Virginia Archived 20 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Diss. 2011. Web. 15 October 2015.

- S. Sansavini (1 July 1986). "The chilling requirement in apple and its role in regulating Time of flowering in spring in cold-Winter Climate". Symposium on Growth Regulators in Fruit Production (International ed.). Acta Horticulturae. p. 179. ISBN 978-90-6605-182-9.

- "Apples". Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- Yepsen, Roger (1994). Apples. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-03690-9.

- "Refrigerated storage of perishable foods". CSIRO. 26 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2007.

- Karp, David (25 October 2006). "Puff the Magic Preservative: Lasting Crunch, but Less Scent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 August 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Lowther, Granville; William Worthington. The Encyclopedia of Practical Horticulture: A Reference System of Commercial Horticulture, Covering the Practical and Scientific Phases of Horticulture, with Special Reference to Fruits and Vegetables. The Encyclopedia of horticulture corporation.

- Coli, William; et al. "Apple Pest Management Guide". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- Bradley, Fern Marshall; Ellis, Barbara W.; Martin, Deborah L., eds. (2009). The Organic Gardener's Handbook of Natural Pest and Disease Control. Rodale, Inc. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-60529-677-7.

- Erler, Fedai (1 January 2010). "Efficacy of tree trunk coating materials in the control of the apple clearwing, Synanthedon myopaeformis". Journal of Insect Science. 10 (1): 63. doi:10.1673/031.010.6301. PMC 3014806. PMID 20672979.

- "Nutrition Facts, Apples, raw, with skin [Includes USDA commodity food A343]. 100 gram amount". Nutritiondata.com, Conde Nast from USDA version SR-21. 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- "Apple Varietals". Washington Apple Commission. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Lim, T. K. (11 June 2012). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 4, Fruits. ISBN 9789400740532.

- "Organic apples". USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "European Organic Apple Production Demonstrates the Value of Pesticides" (PDF). CropLife Foundation, Washington, DC. December 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- Ribeiro FA, Gomes de Moura CF, Aguiar O Jr, de Oliveira F, Spadari RC, Oliveira NR, Oshima CT, Ribeiro DA (September 2014). "The chemopreventive activity of apple against carcinogenesis: antioxidant activity and cell cycle control". European Journal of Cancer Prevention (Review). 23 (5): 477–80. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000005. PMID 24366437.

- Nicolas, J. J.; Richard-Forget, F. C.; Goupy, P. M.; Amiot, M. J.; Aubert, S. Y. (1 January 1994). "Enzymatic browning reactions in apple and apple products". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 34 (2): 109–157. doi:10.1080/10408399409527653. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 8011143.

- "PPO silencing". Okanagan Specialty Fruits, Inc. 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "United States: GM non-browning Arctic apple expands into foodservice". Fresh Fruit Portal. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "Okanagan Specialty Fruits: Biotechnology Consultation Agency Response Letter BNF 000132". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "Questions and answers: Arctic Apple". Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Government of Canada. 8 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Yu, Xiuzhu; Van De Voort, Frederick R.; Li, Zhixi; Yue, Tianli (2007). "Proximate Composition of the Apple Seed and Characterization of Its Oil". International Journal of Food Engineering. 3 (5). doi:10.2202/1556-3758.1283.

- Fabiani, R; Minelli, L; Rosignoli, P (October 2016). "Apple intake and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Public Health Nutrition. 19 (14): 2603–17. doi:10.1017/S136898001600032X. PMID 27000627.

- "General Information – Apple". Informall. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Landau, Elizabeth, Oral allergy syndrome may explain mysterious reactions Archived 15 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 8 April 2009, CNN Health, accessed 17 October 2011

- Lewis S. Nelson; Richard D. Shih; Michael J. Balick (2007). Handbook of poisonous and injurious plants. Springer. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-387-33817-0. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "Amygdalin". Toxnet, US Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

Further reading

Books

- Browning, F. (1999). Apples: The Story of the Fruit of Temptation. North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-579-3.

- Mabberley, D.J; Juniper, B.E (2009). The Story of the Apple. Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-60469-172-6.

- "Humor and Philosophy Relating to Apples". Reading Eagle. Reading, PA. 2 November 1933. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apples. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_National_Fruit_Collection_(acc._1979-159).jpg)

.jpg)