Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan (/tɜːrkˈmɛnɪstæn/ (![]()

![]()

Turkmenistan Türkmenistan[1] | |

|---|---|

Anthem: Garaşsyz Bitarap Türkmenistanyň Döwlet Gimni ("State Anthem of Independent, Neutral Turkmenistan") | |

.svg.png) Location of Turkmenistan (red) | |

| Capital and largest city | Ashgabat 37°58′N 58°20′E |

| Official languages | Turkmen[4] |

| Inter-ethnic languages | Turkmen, Russian[5] |

| Ethnic groups (2010) | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Turkmenistani[6] Turkmen[7] |

| Government | Unitary presidential secular republic |

| Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow | |

| Raşit Meredow | |

• Chairman of the Mejlis | Gülşat Mämmedowa |

| Legislature | |

| People's Council | |

| Mejlis | |

| Formation | |

| 1875 | |

| 13 May 1925 | |

• Declared state sovereignty | 22 August 1990 |

• Declared independence from the Soviet Union | 27 October 1991 |

• Recognized | 26 December 1991 |

| 18 May 1992 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 491,210 km2 (189,660 sq mi)[8] (52nd) |

• Water (%) | 4.9 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 6,031,187 [9] (113th) |

• Density | 10.5/km2 (27.2/sq mi) (221st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $112.659 billion[10] |

• Per capita | $19,526[10] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $42.764 billion[10] |

• Per capita | $7,411[10] |

| Gini (1998) | 40.8 medium |

| HDI (2018) | high · 108th |

| Currency | Turkmen new manat (TMT) |

| Time zone | UTC+05 (TMT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +993 |

| ISO 3166 code | TM |

| Internet TLD | .tm |

Turkmenistan has been at the crossroads of civilizations for centuries. Merv being the oldest of oasis-cities in Central Asia[12] was once the biggest city in the world[13], in medieval times one of the great cities of the Islamic world and an important stop on the Silk Road, a caravan route used for trade with China until the mid-15th century. Annexed by the Russian Empire in 1881, Turkmenistan later figured prominently in the anti-Bolshevik movement in Central Asia. In 1925, Turkmenistan became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkmen SSR); it became independent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[6]

Turkmenistan possesses the world's fourth largest reserves of natural gas.[14] Most of the country is covered by the Karakum (Black Sand) Desert. From 1993 to 2017, citizens received government-provided electricity, water and natural gas free of charge.[15]

The sovereign state of Turkmenistan was ruled by President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov (also known as Turkmenbashi) until his death in 2006. Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was elected president in 2007 (he had been vice-president and then acting president previously). According to Human Rights Watch, "Turkmenistan remains one of the world’s most repressive countries. The country is virtually closed to independent scrutiny, media and religious freedoms are subject to draconian restrictions, and human rights defenders and other activists face the constant threat of government reprisal."[16] After the suspension of the death penalty, the use of capital punishment was formally abolished in the 2008 constitution.[4][17]

Naming

The name of Turkmenistan (Turkmen: Türkmenistan) can be divided into two components: the ethnonym Türkmen and the Persian suffix -stan meaning "place of" or "country". The name "Turkmen" comes from Turk, plus the Sogdian suffix -men, meaning "almost Turk", in reference to their status outside the Turkic dynastic mythological system.[18] However, some scholars argue the suffix is an intensifier, changing the meaning of Türkmen to "pure Turks" or "the Turkish Turks."[19]

Muslim chroniclers like Ibn Kathir suggested that the etymology of Turkmenistan came from the words Türk and Iman (Arabic: إيمان, "faith, belief") in reference to a massive conversion to Islam of two hundred thousand households in the year 971.[20]

Turkmenistan declared its independence from the Soviet Union after the independence referendum in 1991. As a result, the constitutional law had been adopted in October 27th, the Article 1of this law established the new name of the state - Turkmenistan (Türkmenistan' / Түркменистан).[21]

A common name for the Turkmen SSR was Turkmenia (Russian: Туркмения), used in some reports of the country's independence.[22]

History

Historically inhabited by the Indo-Iranians, the written history of Turkmenistan begins with its annexation by the Achaemenid Empire of Ancient Iran. In the 8th century AD, Turkic-speaking Oghuz tribes moved from Mongolia into present-day Central Asia. Part of a powerful confederation of tribes, these Oghuz formed the ethnic basis of the modern Turkmen population.[23] In the 10th century, the name "Turkmen" was first applied to Oghuz groups that accepted Islam and began to occupy present-day Turkmenistan.[23] There they were under the dominion of the Seljuk Empire, which was composed of Oghuz groups living in present-day Iran and Turkmenistan.[23] Oghuz groups in the service of the empire played an important role in the spreading of Turkic culture when they migrated westward into present-day Azerbaijan and eastern Turkey.[23]

In the 12th century, Turkmen and other tribes overthrew the Seljuk Empire.[23] In the next century, the Mongols took over the more northern lands where the Turkmens had settled, scattering the Turkmens southward and contributing to the formation of new tribal groups.[23] The sixteenth and eighteenth centuries saw a series of splits and confederations among the nomadic Turkmen tribes, who remained staunchly independent and inspired fear in their neighbors.[23] By the 16th century, most of those tribes were under the nominal control of two sedentary Uzbek khanates, Khiva and Bukhoro.[23] Turkmen soldiers were an important element of the Uzbek militaries of this period.[23] In the 19th century, raids and rebellions by the Yomud Turkmen group resulted in that group's dispersal by the Uzbek rulers.[23] In 1855 the Turkmen tribe of Teke led by Gowshut-Khan defeated the invading army of the Khan of Khiva Muhammad Amin Khan[24] and in 1861 the invading Persian army of Nasreddin-Shah[25].

In the 2nd half of the 19th century, northern Turkmens were the main military and political power in the Khanate of Khiva[26][27]. According to Paul R. Spickard, "Prior to the Russian conquest, the Turkmen were known and feared for their involvement in the Central Asian slave trade."[28][29]

._%D0%A3_%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%85_%D0%B2%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%82.jpg)

Russian forces began occupying Turkmen territory late in the 19th century.[23] From their Caspian Sea base at Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashy), the Russians eventually overcame the Uzbek khanates.[23] In 1879, the Russian forces were defeated by the Teke Turkmens during the first attempt to conquer the Akhal area of Turkmenistan[30]. However, in 1881, the last significant resistance in Turkmen territory was crushed at the Battle of Geok Tepe, and shortly thereafter Turkmenistan was annexed, together with adjoining Uzbek territory, into the Russian Empire.[23] In 1916, the Russian Empire's participation in World War I resonated in Turkmenistan, as an anticonscription revolt swept most of Russian Central Asia.[23] Although the Russian Revolution of 1917 had little direct impact, in the 1920s Turkmen forces joined Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Uzbeks in the so-called Basmachi Rebellion against the rule of the newly formed Soviet Union.[23] In 1924, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was formed from the tsarist province of Transcaspia.[23] By the late 1930s, Soviet reorganization of agriculture had destroyed what remained of the nomadic lifestyle in Turkmenistan, and Moscow controlled political life.[23] The Ashgabat earthquake of 1948 killed over 110,000 people,[31] amounting to two-thirds of the city's population.

During the next half-century, Turkmenistan played its designated economic role within the Soviet Union and remained outside the course of major world events.[23] Even the major liberalization movement that shook Russia in the late 1980s had little impact.[23] However, in 1990, the Supreme Soviet of Turkmenistan declared sovereignty as a nationalist response to perceived exploitation by Moscow.[23] Although Turkmenistan was ill-prepared for independence and then-communist leader Saparmurat Niyazov preferred to preserve the Soviet Union, in October 1991, the fragmentation of that entity forced him to call a national referendum that approved independence.[23] On 26 December 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Niyazov continued as Turkmenistan's chief of state, replacing communism with a unique brand of independent nationalism reinforced by a pervasive cult of personality.[23] A 1994 referendum and legislation in 1999 abolished further requirements for the president to stand for re-election (although in 1992 he completely dominated the only presidential election in which he ran, as he was the only candidate and no one else was allowed to run for the office), making him effectively president for life.[23] During his tenure, Niyazov conducted frequent purges of public officials and abolished organizations deemed threatening.[23] Throughout the post-Soviet era, Turkmenistan has taken a neutral position on almost all international issues.[23] Niyazov eschewed membership in regional organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and in the late 1990s he maintained relations with the Taliban and its chief opponent in Afghanistan, the Northern Alliance.[23] He offered limited support to the military campaign against the Taliban following the 11 September 2001 attacks.[23] In 2002 an alleged assassination attempt against Niyazov led to a new wave of security restrictions, dismissals of government officials, and restrictions placed on the media.[23] Niyazov accused exiled former foreign minister Boris Shikhmuradov of having planned the attack.[23]

Between 2002 and 2004, serious tension arose between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan because of bilateral disputes and Niyazov's implication that Uzbekistan had a role in the 2002 assassination attempt.[23] In 2004, a series of bilateral treaties restored friendly relations.[23] In the parliamentary elections of December 2004 and January 2005, only Niyazov's party was represented, and no international monitors participated.[23] In 2005, Niyazov exercised his dictatorial power by closing all hospitals outside Ashgabat and all rural libraries.[23] The year 2006 saw intensification of the trends of arbitrary policy changes, shuffling of top officials, diminishing economic output outside the oil and gas sector, and isolation from regional and world organizations.[23] China was among a very few nations to whom Turkmenistan made significant overtures.[23] The sudden death of Niyazov at the end of 2006 left a complete vacuum of power, as his cult of personality, comparable to the one of eternal president Kim Il-sung of North Korea, had precluded the naming of a successor.[23] Deputy Prime Minister Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who was named interim head of government, won the special presidential election held in early February 2007.[23] He was re-elected in 2012 with 97% of the vote.[32]

Politics

| External video | |

|---|---|

.jpg)

After 69 years as part of the Soviet Union (including 67 years as a union republic), Turkmenistan declared its independence on 27 October 1991.

President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov, a former bureaucrat of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, ruled Turkmenistan from 1985, when he became head of the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR, until his death in 2006. He retained absolute control over the country after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. On 28 December 1999, Niyazov was declared President for Life of Turkmenistan by the Mejlis (parliament), which itself had taken office a week earlier in elections that included only candidates hand-picked by President Niyazov. No opposition candidates were allowed.

Since the December 2006 death of Niyazov, Turkmenistan's leadership has made tentative moves to open up the country. His successor, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, repealed some of Niyazov's most idiosyncratic policies, including banning opera and the circus for being "insufficiently Turkmen". In education, Berdimuhamedow's government increased basic education to ten years from nine years, and higher education was extended from four years to five. It also increased contacts with the West, which is eager for access to the country's natural gas riches.

The politics of Turkmenistan take place in the framework of a presidential republic, with the President both head of state and head of government. Under Niyazov, Turkmenistan had a one-party system; however, in September 2008, the People's Council unanimously passed a resolution adopting a new Constitution. The latter resulted in the abolition of the Council and a significant increase in the size of Parliament in December 2008 and also permits the formation of multiple political parties.

The former Communist Party, now known as the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan, is the dominant party. The second party, the Party of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs was established in August 2012. Political gatherings are illegal unless government sanctioned. In 2013, the first multi-party Parliamentary Elections were held in Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan was a one-party state from 1991 to 2012; however, the 2013 elections were widely seen as mere window dressing.[33] In practice, all parties in parliament operate jointly under the direction of the DPT. There are no true opposition parties in the Turkmen parliament.[34]

Foreign relations

.jpg)

_06.jpg)

Turkmenistan's declaration of "permanent neutrality" was formally recognized by the United Nations in 1995.[35] Former President Saparmurat Niyazov stated that the neutrality would prevent Turkmenistan from participating in multi-national defense organizations, but allows military assistance. Its neutral foreign policy has an important place in the country's constitution. Turkmenistan has diplomatic relations with 139 countries.[36]

List of international organization memberships

- Organization of Islamic Cooperation[37]

Human rights

Turkmenistan has been widely criticised for human rights abuses and has imposed severe restrictions on foreign travel for its citizens.[38] Discrimination against the country's ethnic minorities remains in practice. Universities have been encouraged to reject applicants with non-Turkmen surnames, especially ethnic Russians.[39] It is forbidden to teach the customs and language of the Baloch, an ethnic minority.[40] The same happens to Uzbeks, though the Uzbek language was formerly taught in some national schools.[40]

According to Reporters Without Borders's 2014 World Press Freedom Index, Turkmenistan had the 3rd worst press freedom conditions in the world (178/180 countries), just before North Korea and Eritrea.[41] It is considered to be one of the "10 Most Censored Countries". Each broadcast under Niyazov began with a pledge that the broadcaster's tongue will shrivel if he slanders the country, flag, or president.[42]

Religious minorities are discriminated against for conscientious objection and practicing their religion by imprisonment, preventing foreign travel, confiscating copies of Christian literature or defamation.[43][44][45] Many detainees who have been arrested for exercising their freedom of religion or belief, were tortured and subsequently sentenced to imprisonment, many of them without a court decision.[46][47] Homosexual acts are illegal in Turkmenistan.[48]

Restrictions on free and open communication

Despite the launch of Turkmenistan's first communication satellite—TurkmenSat 1—in April 2015, the Turkmen government banned all satellite dishes in Turkmenistan the same month. The statement issued by the government indicated that all existing satellite dishes would have to be removed or destroyed—despite the communications receiving antennas having been legally installed since 1995—in an effort by the government to fully block access of the population to many "hundreds of independent international media outlets" which are currently accessible in the country only through satellite dishes, including all leading international news channels in different languages. The main target of this campaign is Radio Azatlyk, the Turkmen-language service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. It is the only independent source of information about Turkmenistan and the world in the Turkmen language and is widely listened to in the country."[49]

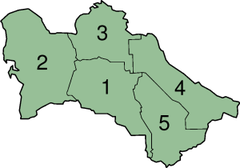

Administrative divisions

Turkmenistan is divided into five provinces or welayatlar (singular welayat) and one capital city district. The provinces are subdivided into districts (etraplar, sing. etrap), which may be either counties or cities. According to the Constitution of Turkmenistan (Article 16 in the 2008 Constitution, Article 47 in the 1992 Constitution), some cities may have the status of welaýat (province) or etrap (district).

| Division | ISO 3166-2 | Capital city | Area[50] | Pop (2005)[50] | Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashgabat City | TM-S | Ashgabat | 470 km2 (180 sq mi) | 871,500 | |

| Ahal Province | TM-A | Anau | 97,160 km2 (37,510 sq mi) | 939,700 | 1 |

| Balkan Province | TM-B | Balkanabat | 139,270 km2 (53,770 sq mi) | 553,500 | 2 |

| Daşoguz Province | TM-D | Daşoguz | 73,430 km2 (28,350 sq mi) | 1,370,400 | 3 |

| Lebap Province | TM-L | Türkmenabat | 93,730 km2 (36,190 sq mi) | 1,334,500 | 4 |

| Mary Province | TM-M | Mary | 87,150 km2 (33,650 sq mi) | 1,480,400 | 5 |

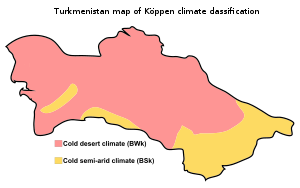

Climate

The Karakum Desert is one of the driest deserts in the world; some places have an average annual precipitation of only 12 mm (0.47 in). The highest temperature recorded in Ashgabat is 48.0 °C (118.4 °F) and Kerki, an extreme inland city located on the banks of the Amu Darya river, recorded 51.7 °C (125.1 °F) in July 1983, although this value is unofficial. 50.1 °C (122 °F) is the highest temperature recorded at Repetek Reserve, recognized as the highest temperature ever recorded in the whole former Soviet Union.

Geography

At 488,100 km2 (188,500 sq mi), Turkmenistan is the world's 52nd-largest country. It is slightly smaller than Spain and somewhat larger than the US state of California. It lies between latitudes 35° and 43° N, and longitudes 52° and 67° E. Over 80% of the country is covered by the Karakum Desert. The center of the country is dominated by the Turan Depression and the Karakum Desert. The Kopet Dag Range, along the southwestern border, reaches 2,912 metres (9,554 feet) at Kuh-e Rizeh (Mount Rizeh).[51]

The Great Balkhan Range in the west of the country (Balkan Province) and the Köýtendag Range on the southeastern border with Uzbekistan (Lebap Province) are the only other significant elevations. The Great Balkhan Range rises to 1,880 metres (6,170 ft) at Mount Arlan[52] and the highest summit in Turkmenistan is Ayrybaba in the Kugitangtau Range – 3,137 metres (10,292 ft).[53] The Kopet Dag mountain range forms most of the border between Turkmenistan and Iran. Rivers include the Amu Darya, the Murghab, and the Tejen.

The climate is mostly arid desert with subtropical temperature ranges and little rainfall. Winters are mild and dry, with most precipitation falling between January and May. The area of the country with the heaviest precipitation is the Kopet Dag Range.

The Turkmen shore along the Caspian Sea is 1,748 kilometres (1,086 mi) long. The Caspian Sea is entirely landlocked, with no natural access to the ocean, although the Volga–Don Canal allows shipping access to and from the Black Sea.

The major cities include Aşgabat, Türkmenbaşy (formerly Krasnovodsk) and Daşoguz.

Environment

Turkmenistan's greenhouse gas emissions per person (17.5 tCO2e) are considerably higher than the OECD average: due to natural gas seepage from oil and gas exploration, and very high energy subsidies.[54]

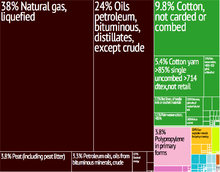

Economy

The country possesses the world's fourth largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources.[55]

Turkmenistan has taken a cautious approach to economic reform, hoping to use gas and cotton sales to sustain its economy. In 2014, the unemployment rate was estimated to be 11%.[6]

Between 1998 and 2002, Turkmenistan suffered from the continued lack of adequate export routes for natural gas and from obligations on extensive short-term external debt. At the same time, however, the value of total exports has risen sharply because of increases in international oil and gas prices. Economic prospects in the near future are discouraging because of widespread internal poverty and the burden of foreign debt.

President Niyazov spent much of the country's revenue on extensively renovating cities, Ashgabat in particular. Corruption watchdogs voiced particular concern over the management of Turkmenistan's currency reserves, most of which are held in off-budget funds such as the Foreign Exchange Reserve Fund in the Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt, according to a report released in April 2006 by London-based non-governmental organization Global Witness.

According to the decree of the Peoples' Council of 14 August 2003,[56] electricity, natural gas, water and salt will be subsidized for citizens up to 2030. Under current regulations, every citizen is entitled to 35 kilowatt hours of electricity and 50 cubic meters of natural gas each month. The state also provides 250 liters (66 gallons) of water per day.[57]

Natural gas and export routes

As of May 2011, the Galkynysh Gas Field has the second-largest volume of gas in the world, after the South Pars field in the Persian Gulf. Reserves at the Galkynysh Gas Field are estimated at around 21.2 trillion cubic metres.[58] The Turkmenistan Natural Gas Company (Türkmengaz), under the auspices of the Ministry of Oil and Gas, controls gas extraction in the country. Gas production is the most dynamic and promising sector of the national economy. In 2010 Ashgabat started a policy of diversifying export routes for its raw materials.[59] China is the largest buyer of gas from Turkmenistan, via a pipeline linking the two countries through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[60] and Ashgabat's main external financial donor.[61] In addition to supplying Russia, China and Iran, Ashgabat took concrete measures to accelerate progress in the construction of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan and India pipeline (TAPI). Turkmenistan has previously estimated the cost of the project at $3.3 billion.

Oil

Most of Turkmenistan's oil is extracted by the Turkmenistan State Company (Concern) Türkmennebit from fields at Koturdepe, Balkanabat, and Cheleken near the Caspian Sea, which have a combined estimated reserve of 700 million tons. The oil extraction industry started with the exploitation of the fields in Cheleken in 1909 (by Branobel) and in Balkanabat in the 1930s. Production leaped ahead with the discovery of the Kumdag field in 1948 and the Koturdepe field in 1959. A big part of the oil produced in Turkmenistan is refined in Turkmenbashy and Seidi refineries. Also, oil is exported by tankers through the Caspian Sea to Europe via canals.[62]

Energy

Turkmenistan is a net exporter of electrical power to Central Asian republics and southern neighbors. The most important generating installations are the Hindukush Hydroelectric Station, which has a rated capacity of 350 megawatts, and the Mary Thermoelectric Power Station, which has a rated capacity of 1,370 megawatts. In 1992, electrical power production totaled 14.9 billion kilowatt-hours.[63]

Agriculture

In Turkmenistan, most of irrigated land is planted with cotton, making the country the world's ninth-largest cotton producer.[64]

During the 2011 season, Turkmenistan produced around 1.1 million tons of raw cotton, mainly from Mary, Balkan, Akhal, Lebap and Dashoguz provinces. In 2012, around 7,000 tractors, 5,000 cotton cultivators, 2,200 sowing machines and other machinery, mainly procured from Belarus and the United States, are being used. The country traditionally exports raw cotton to Russia, Iran, South Korea, United Kingdom, China, Indonesia, Turkey, Ukraine, Singapore and the Baltic states.[65]

Tourism

The tourism industry has been growing rapidly in recent years, especially medical tourism. This is primarily due to the creation of the Awaza tourist zone on the Caspian Sea.[66] Every traveler must obtain a visa before entering Turkmenistan (see Visa policy of Turkmenistan). To obtain a tourist visa, citizens of most countries need visa support from a local travel agency. For tourists visiting Turkmenistan, there are organized tours with a visit to historical sites Daşoguz, Konye-Urgench, Nisa, Merv, Mary, beach tours to Avaza and medical tours and holidays in Mollakara, Ýylysuw and Archman.

Demographics

| Population[67][68] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 1.2 | ||

| 2000 | 4.5 | ||

| 2018 | 5.9 | ||

Most of Turkmenistan's citizens are ethnic Turkmens with sizeable minorities of Uzbeks and Russians. Smaller minorities include Kazakhs, Tatars, Ukrainians, Kurds (native to Kopet Dagh mountains), Armenians, Azeris, Balochs and Pashtuns. The percentage of ethnic Russians in Turkmenistan dropped from 18.6% in 1939 to 9.5% in 1989. In 2012, it was confirmed that the population of Turkmenistan decreased due to some specific factors and is less than the previously estimated 5 million.[69] Citizens of Turkmenistan are known as Turkmenistanis.[6]

The CIA World Factbook gives the ethnic composition of Turkmenistan as 85% Turkmen, 5% Uzbek, 4% Russian and 6% other (2003 estimates).[6] According to data announced in Ashgabat in February 2001, 91% of the population are Turkmen, 3% are Uzbeks and 2% are Russians. Between 1989 and 2001 the number of Turkmen in Turkmenistan doubled (from 2.5 to 4.9 million), while the number of Russians dropped by two-thirds (from 334,000 to slightly over 100,000).[70]

Largest cities

Languages

Turkmen is the official language of Turkmenistan (per the 1992 Constitution), although Russian still is widely spoken in cities as a "language of inter-ethnic communication". Turkmen is spoken by 72% of the population, Russian by 12% (349,000), Uzbek by 9%[6] (317,000), and other languages by 7% (Kazakh (88,000), Tatar (40,400), Ukrainian (37,118), Azerbaijani (33,000), Armenian (32,000), Northern Kurdish (20,000), Lezgian (10,400), Persian (8,000), Belarusian (5,290), Erzya (3,490), Korean (3,490), Bashkir (2,610), Karakalpak (2,540), Ossetic (1,890), Dargwa (1,600), Lak (1,590), Tajik (1,280), Georgian (1,050), Lithuanian (224), Tabasaran (180), Dungan).[71]

Religion

According to the CIA World Factbook, Muslims constitute 93% of the population while 6% of the population are followers of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the remaining 1% religion is reported as non-religious.[6] According to a 2009 Pew Research Center report, 93.1% of Turkmenistan's population is Muslim.[73]

The first migrants were sent as missionaries and often were adopted as patriarchs of particular clans or tribal groups, thereby becoming their "founders." Reformulation of communal identity around such figures accounts for one of the highly localized developments of Islamic practice in Turkmenistan.[74]

In the Soviet era, all religious beliefs were attacked by the communist authorities as superstition and "vestiges of the past." Most religious schooling and religious observance were banned, and the vast majority of mosques were closed. However, since 1990, efforts have been made to regain some of the cultural heritage lost under Soviet rule.

Former president Saparmurat Niyazov ordered that basic Islamic principles be taught in public schools. More religious institutions, including religious schools and mosques, have appeared, many with the support of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Turkey. Religious classes are held in both schools and mosques, with instruction in Arabic language, the Qur'an and the hadith, and history of Islam.[75]

President Niyazov wrote his own religious text, published in separate volumes in 2001 and 2004, entitled the Ruhnama. The Turkmenbashi regime required that the book, which formed the basis of the educational system in Turkmenistan, be given equal status with the Quran (mosques were required to display the two books side by side). The book was heavily promoted as part of the former president's personality cult, and knowledge of the Ruhnama is required even for obtaining a driver's license.[76]

Most Christians in Turkmenistan belong to Eastern Orthodoxy (about 5% of the population).[77] The Russian Orthodox Church is under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Archbishop in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.[78] There are three Russian Orthodox Churches in Ashgabat, two in Turkmenabat, in Mary, Turkmenbashi, Balkanabat, Bayram-Ali and Dushauguze one each.[77] The highest Russian Orthodox priest in Turkmenistan is based in Ashgabat.[79] There is one Russian orthodox monastery, in Ashgabat.[79] Turkmenistan has no Russian Orthodox seminary, however.[79]

There are also small communities of the following denominations: the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Pentecostal Christians, the Protestant Word of Life Church, the Greater Grace World Outreach Church, the New Apostolic Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, Jews, and several unaffiliated, nondenominational evangelical Christian groups. In addition, there are small communities of Baha'is, Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, and Hare Krishnas.[43]

The history of Bahá'í Faith in Turkmenistan is as old as the religion itself, and Bahá'í communities still exist today.[80] The first Bahá'í House of Worship was built in Ashgabat at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was seized by the Soviets in the 1920s and converted to an art gallery. It was heavily damaged in the earthquake of 1948 and later demolished. The site was converted to a public park.[81]

Culture

Heritage

| Image | Name | Location | Notes | Date added | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient Merv | Baýramaly, Mary Region | a major oasis-city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road | 1995 | Cultural[82] |

|

Köneürgenç | Köneürgenç | unexcavated ruins of the 12th-century capital of Khwarazm | 2005 | Cultural[83] |

|

Parthian Fortresses of Nisa | Bagyr, Ahal Province | one of the first capitals of the Parthians | 2007 | Cultural[84] |

Mass media

There are a number of newspapers and monthly magazines published and online news-portal Turkmenportal in Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan currently broadcasts 7 national TV channels through satellite. They are Altyn asyr, Yashlyk, Miras, Turkmenistan (in 7 languages), Türkmen Owazy, Turkmen sporty and Ashgabat. There are no commercial or private TV stations. Articles published by the state-controlled newspapers are heavily censored and written to glorify the state and its leader.

| External video | |

|---|---|

Internet services are the least developed in Central Asia. Access to Internet services are provided by the government's ISP company "Turkmentelekom". As of 31 December 2011, it was estimated that there were 252,741 internet users in Turkmenistan or roughly 5% of total population.[85][6]

Education

.jpg)

Education is universal and mandatory through the secondary level, the total duration of which was earlier reduced from 10 to 9 years; with the new President it has been decreed that from the 2007–2008 school year on, mandatory education will be for 10 years. From 2013 secondary general education in Turkmenistan is a three-stage secondary schools for 12 years according to the following steps: Elementary school (grades 1–3), High School – the first cycle of secondary education with duration of 5 years (4–8 classes), Secondary school – the second cycle of secondary education, shall be made within 4 years (9–12 classes).[86][87]

At the end of the 2019/2020 academic year, nearly 80,000 Turkmen pupils were graduated from high school.[88] As of the 2019/2020 academic year, 12,242 of these students were admitted to institutions of higher education in Turkmenistan. An additional 9,063 were admitted to the country's 42 vocational colleges.[89]

Architecture

The task for modern Turkmen architecture is diverse application of modern aesthetics, the search for an architect's own artistic style and inclusion of the existing historico-cultural environment. Most buildings are faced with white marble. Major projects such as Turkmenistan Tower, Bagt köşgi, Alem Cultural and Entertainment Center have transformed the country's skyline and promotes its contemporary identity.

Sports

Transportation

Automobile transport

Construction of new and modernization of existing roads has an important role in the development of the country. With the increase in traffic flow is adjusted already built roads, as well as the planned construction of new highways. Construction of roads and road transport has always paid great attention. So, in 2004, Baimukhamet Kelov was removed from office by the Minister of road transport and highways Turkmenistan for embezzlement of public funds and deficiencies in the work.[90]

Air transport

Turkmenistan's cities of Turkmenbashi and Ashgabat both have scheduled commercial air service. The largest airport is Ashgabat Airport, with regular international flights. Additionally, scheduled international flights are available to Turkmenbashi. The principal government-managed airline of Turkmenistan is Turkmenistan Airlines. It is also the largest airline operating in Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan Airlines' passenger fleet is composed only of United States Boeing aircraft.[91] Air transport carries more than two thousand passengers daily in the country.[92] International flights annually transport over half a million people into and out of Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan Airlines operates regular flights to Moscow, London, Frankfurt, Birmingham, Bangkok, Delhi, Abu Dhabi, Amritsar, Kiev, Lviv, Beijing, Istanbul, Minsk, Almaty, Tashkent, and St. Petersburg.

Maritime transport

.jpg)

Since 1962, the Turkmenbashi International Seaport operates a ferry to the port of Baku, Azerbaijan. In recent years there has been increased tanker transport of oil. The port of Turkmenbashi, associated rail ferries to the ports of the Caspian Sea (Baku, Aktau). In 2011, it was announced that the port of Turkmenbashi will be completely renovated. The project involves the reconstruction of the terminal disassembly of old and construction of new berths.[93][94]

Railway transport

Rail is one of the main modes of transport in Turkmenistan. Trains have been used in the nation since 1876. Originally, it was part of the Trans-Caspian railway, then the Central Asian Railway, after the collapse of the USSR, the railway network in Turkmenistan owned and operated by state-owned Türkmendemirýollary. The total length of railways is 3181 km. The passenger traffic railways of Turkmenistan are limited by the national borders of the country, except in the areas along which the transit trains are coming from Tajikistan to Uzbekistan and beyond. Locomotive fleet consists of a series of soviet-made locomotives 2TE10L, 2TE10U, 2M62U also have several locomotives made in China. Shunting locomotives include Soviet-made TEM2, TEM2U, CME3. Currently under construction railway Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran and Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Tajikistan.

References

- Hambly, Gavin R.G.; et al. "Turkmenistan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Editor. ""Turkmenistan is the motherland of Neutrality" is the motto of 2020 | Chronicles of Turkmenistan". En.hronikatm.com. Retrieved 26 May 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- 29.12.2019 (29 December 2019). "Turkmen parliament places Year 2020 under national motto "Turkmenistan – Homeland of Neutrality" – tpetroleum". Turkmenpetroleum.com. Retrieved 26 May 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Turkmenistan's Constitution of 2008. constituteproject.org

- "Туркменский парадокс: русского языка де-юре нет, де-факто он необходим". Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting. CABAR. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Turkmenistan". The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Dual Citizenship". Ashgabat: U.S. Embassy in Turkmenistan. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Государственный комитет Туркменистана по статистике : Информация о Туркменистане : О Туркменистане Archived 7 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine : Туркменистан — одна из пяти стран Центральной Азии, вторая среди них по площади (491,21 тысяч км2), расположен в юго-западной части региона в зоне пустынь, севернее хребта Копетдаг Туркмено-Хорасанской горной системы, между Каспийским морем на западе и рекой Амударья на востоке.

- https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Files/1_Indicators%20(Standard)/EXCEL_FILES/1_Population/WPP2019_POP_F01_1_TOTAL_POPULATION_BOTH_SEXES.xlsx

- "Turkmenistan". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "State Historical and Cultural Park "Ancient Merv"". UNESCO-WHC.

- Tharoor, Kanishk (2016). "LOST CITIES #5: HOW THE MAGNIFICENT CITY OF MERV WAS RAZED – AND NEVER RECOVERED". The Guardian.

Once the world’s biggest city, the Silk Road metropolis of Merv in modern Turkmenistan destroyed by Genghis Khan’s son and the Mongols in AD1221 with an estimated 700,000 deaths.

- "BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019" (PDF). p. 30.

- "Turkmen ruler ends free power, gas, water – World News". Hürriyet Daily News.

- "World Report 2014: Turkmenistan". Hrw.org. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Asia-Pacific – Turkmenistan suspends death penalty". BBC News.

- Zuev, Yury (2002). Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology. Almatý: Daik-Press. p. 157.

- US Library of Congress Country Studies. "Turkmenistan."

- Ibn Kathir al-Bidaya wa al-Nihaya. (in Arabic)

- Constitutional Law of Turkmenistan on independence and the fundamentals of the state organisation of Turkmenistan; Ведомости Меджлиса Туркменистана", № 15, page 152 – 27 October 1991. Retrieved from the Database of Legislation of Turkmenistan, OSCE Centre in Ashgabat.

- Independence of Turkmenia Declared After a Referendum; New York Times – 28 October 1991. Retrieved on 16 November 2016.

- "Country Profile: Turkmenistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. February 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Аннанепесов (Annanepesov), М. (M.) (2000). Gundogdyyev, Ovez (ed.). "Серахское сражение 1855 года (Историко-культурное наследие Туркменистана)" [Serakhs Battle of 1855 (Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan)] (in Russian). Istanbul: UNDP.

- Казем-Заде (Kazem-Zade), Фируз (Firuz) (2017). "Борьба за влияние в Персии. Дипломатическое противостояние России и Англии" [Struggle for Influence in Persia. Diplomatic Confrontation between Russia and England] (in Russian). Центрполиграф (Centrpoligraph).

- MacGahan, Januarius (1874). "Campaigning on the Oxus, and the fall of Khiva". New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Глуховской (Glukhovskoy), А. (1873). "О положении дел в Аму Дарьинском бассейне" [On the State of Affairs in the Amu Darya Basin] (in Russian).

- Paul R. Spickard (2005). Race and Nation: Ethnic Systems in the Modern World. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-415-95003-9.

- Scott Cameron Levi (January 2002). The Indian Diaspora in Central Asia and Its Trade: 1550–1900. BRILL. p. 68. ISBN 978-90-04-12320-5.

- Аннанепесов (Annanepesov), М. (M.) (2000). "Ахалтекинские экспедиции (Историко-культурное наследие Туркменистана)" [Akhal-Teke Expeditions (Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan)] (in Russian). UNDP.

- "Comments for the significant earthquake". Significant Earthquake Database. National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Turkmenistan president wins election with 96.9% of vote". theguardian.com. London. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Turkmenistan". 8 September 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Stronski, Paul (22 May 2017). Независимому Туркменистану двадцать пять лет: цена авторитаризма. carnegie.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "A/RES/50/80. Maintenance of international security". un.org.

- "Diplomatic relations". Mfa.gov.tm. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Member States". OIC.

- "Russians 'flee' Turkmenistan". BBC News. 20 June 2003. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Turkmenistan: Russian Students Targeted". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. 21 February 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Alternative report on the Human Rights situation in Turkmenistan for the Universal Periodic Review" (PDF) (Press release). FIDH. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- "Reporters Without Borders". rsf.org. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "10 Most Censored Countries". Cpj.org. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "Turkmenistan: International Religious Freedom Report 2004". www.state.gov/. United States Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 21 May 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Turkmenistan 2015/2016: Freedom of religion". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "One Year of Unjust Imprisonment in Turkmenistan". jw.org.

- Service, Forum 18 News. "Forum 18: TURKMENISTAN: Torture and jail for one 4 year and 14 short-term prisoners of conscience – 21 May 2015". www.forum18.org. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Turkmenistan". Human Rights Watch. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "LGBT relationships are illegal in 74 countries, research finds". The Independent. 17 May 2016.

- Forrester, Chris (22 April 2015). "Satellite dishes banned in Turkmenistan". Advanced Television. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Statistical Yearbook of Turkmenistan 2000–2004, National Institute of State Statistics and Information of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat, 2005.

- Kuh-e Rizeh on Peakbagger.com

- "Mount Arlan". Peakbagger.com. 1 November 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "Ayrybaba". Peakbagger.com. 1 November 2004. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Strategic Infrastructure Planning for Sustainable Development in Turkmenistan". OECD. 24 September 2019.

- "BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019" (PDF).

- Resolution of Khalk Maslahati (Peoples' Council of Turkmenistan) N 35 (14 August 2003)

- "Turkmenistan leader wants to end free power, gas, and water". 6 July 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Solovyov, Dmitry (25 May 2011). "Turkmen gas field to be world's second-largest". Reuters.

- "Turkmenistan. Diversifying export routes". Europarussia.com. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "China plays Pipelineistan'". Atimes.com. 24 December 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Vakulchuk, Roman and Indra Overland (2019) “China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the Lens of Central Asia”, in Fanny M. Cheung and Ying-yi Hong (eds) Regional Connection under the Belt and Road Initiative. The Prospects for Economic and Financial Cooperation. London: Routledge, pp. 115–133.

- "Turkmenistan Oil and Gas". Turkmenistanoil.tripod.com. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Turkmenistan study". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "The ten largest cotton producing countries in 2009". Statista.com. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Turkmenistan to Privilege US Farm Machinery Manufacturers". The Gazette of Central Asia. Satrapia. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Las Vegas on the Caspian?". aljazeera.com.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Moya Flynn (2004). Migrant Resettlement in the Russian Federation: Reconstructing 'homes' and 'homelands'. Anthem Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84331-117-1.

- "Ethnic composition of Turkmenistan in 2001" (37–38). Demoscope Weekly. 14 April 2001. Retrieved 25 November 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ethnologue (19 February 1999). "Ethnologue". Ethnologue. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- MAPPING THE GLOBAL MUSLIM POPULATION. pewforum.org (October 2009)

- "MAPPING THE GLOBAL MUSLIM POPULATION : A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population" (PDF). Pweforum.org. October 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- Mark Juergensmeyer; Wade Clark Roof (18 October 2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. pp. 1312–. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- Larry Clark; Michael Thurman & David Tyson (March 1996). Glenn E. Curtis (ed.). "A Country Study: Turkmenistan". Library of Congress Federal Research Division. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Asia-Pacific | Turkmen drivers face unusual test". BBC News. 2 August 2004. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "Столетие.ru: "Туркменбаши хотел рухнамезировать Православие" / Статьи / Патриархия.ru". Patriarchia.ru. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Turkmenistan". State.gov. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Turkmenistan". State.gov. Archived from the original on 30 November 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Turkmenistan". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- Herrmann, Duane L. (Fall 1994) "Houses As perfect As Is Possible" World Order pp. 17–31

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (26 January 2009). "Ancient Merv State Historical and Cultural Park". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (15 July 2005). "Köneürgenç". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Nisa Fortress". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Retrieved: 5 April 2013". Internetworldstats.com. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Turkmenistan adopts 12-year secondary education". Trend. 2 March 2013.

- "Turkmenistan: golden age". turkmenistan.gov.tm.

- "Состоялись мероприятия по случаю окончания учебного года" (in Russian). Государственное информационное агентство Туркменистана (TDH) - Туркменистан сегодня. 25 May 2020.

- {{url=https://www.mfa.gov.tm/ru/articles/8|title=ОБРАЗОВАНИЕ|language=Russian}}

- "Туркменистан: Ниязов решил добить уволенного министра траспорта". Uadaily.net. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Мы не подведём". Ogoniok.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- V@DIM. "Могучие крылья страны". Turkmenistan.gov.tm. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Порт Туркменбаши будет полностью реконструирован". Portnews.ru. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- V@DIM (16 May 2012). "Определены приоритетные направления развития транспорта и транзита в регионе". Turkmenistan.gov.tm. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

Further reading

- Brummel, Paul (2006). Bradt Travel Guide: Turkmenistan. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-144-9.

- Abazov, Rafis (2005). Historical Dictionary of Turkmenistan. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5362-1.

- Clammer, Paul; Kohn, Michael; Mayhew, Bradley (2014). Lonely Planet Guide: Central Asia. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-953-8.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1992). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-1-56836-022-5.

- Blackwell, Carole (2001). Tradition and Society in Turkmenistan: Gender, Oral Culture and Song. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1354-7.

- Kaplan, Robert (2001). Eastward to Tartary: Travels in the Balkans, the Middle East, and the Caucasus. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-375-70576-2.

- Kropf, John (2006). Unknown Sands: Journeys Around the World's Most Isolated Country. Dusty Spark Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9763565-1-6.

- Nahaylo, Bohdan and Victor Swoboda. Soviet Disunion: A History of the Nationalities problem in the USSR (1990) excerpt

- Rall, Ted (2006). Silk Road to Ruin: Is Central Asia the New Middle East?. NBM Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56163-454-5.

- Rashid, Ahmed. The Resurgence of Central Asia: Islam or Nationalism? (2017)

- Rasizade, Alec (2003). Turkmenbashi and his Turkmenistan. = Contemporary Review (Oxford), October 2003, volume 283, number 1653, pages 197-206.

- Smith, Graham, ed. The Nationalities Question in the Soviet Union (2nd ed. 1995)

- Theroux, Paul (28 May 2007). "The Golden Man: Saparmurat Niyazov's reign of insanity". The New Yorker.

- Vilmer, Jean-Baptiste (2009). Turkménistan (in French). Editions Non Lieu. ISBN 978-2352700685.

External links

- "Turkmenistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Modern Turkmenistan photos

- Turkmenistan at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Turkmenistan at Curlie

- Turkmenistan profile from the BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for Turkmenistan from International Futures

- Government

- Turkmenistan government information portal

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Tourism Committee of Turkmenistan

- Other

.jpg)

.svg.png)