Democratic Party (Italy)

The Democratic Party (Italian: Partito Democratico, PD) is a social-democratic[2][3][4] political party in Italy. The party's secretary is Nicola Zingaretti, who was elected in March 2019,[10] while its president is Valentina Cuppi.[11]

The PD was founded on 14 October 2007 upon the merger of various centre-left parties which had been part of The Olive Tree list and The Union coalition in the 2006 general election. They notably included the social-democratic Democrats of the Left (DS), successors of the Italian Communist Party and the Democratic Party of the Left which was folded with several social-democratic parties (Labour Federation and Social Christians, among others) in 1998; and the largely Catholic-inspired Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy (DL), merger of the Italian People's Party (heir of the Christian Democracy party's left-wing), The Democrats and Italian Renewal in 2002.[12] Thus, the party's main ideological trends are social democracy and the Italian Christian leftist tradition.[13][14][15] The PD has been also influenced by social liberalism which was already present in some of the founding components of the DS and DL and more generally by a Third Way progressivism.

The PD was the second-largest party in Italy in the 2018 general election. Between 2013 and 2018, the Italian government was led by three successive Democratic Prime Ministers, namely Enrico Letta (2013–2014), Matteo Renzi (2014–2016) and Paolo Gentiloni (2016–2018). Since September 2019 the party has been part of the Conte II Cabinet, in a coalition with the Five Star Movement. The party also heads six regional governments.

Prominent Democrats include Walter Veltroni (secretary, 2007–2009), Dario Franceschini (secretary, 2009), Maurizio Martina (secretary, 2018), David Sassoli, Piero Fassino, Marco Minniti, Graziano Delrio, Pier Carlo Padoan, Federica Mogherini, Debora Serracchiani, Lorenzo Guerini, Matteo Orfini, Luigi Zanda, Stefano Bonaccini, Sergio Chiamparino, Vincenzo De Luca, Michele Emiliano, Giuseppe Sala, Leoluca Orlando, Virginio Merola and Dario Nardella. Former members include Giorgio Napolitano (President of Italy, 2006–2015), Sergio Mattarella (President of Italy, 2015–present), Romano Prodi, Giuliano Amato, Massimo D'Alema, Pier Luigi Bersani (secretary, 2009–2013), Guglielmo Epifani (secretary, 2013), Francesco Rutelli, Pietro Grasso, Carlo Calenda and Matteo Renzi (secretary, 2013–2018).

History

Background: The Olive Tree

Following Tangentopoli scandals, the end of the so-called First Republic and the transformation of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) into the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS) in the early 1990s, a process aimed at uniting left-wing and centre-left forces into a single political entity was started.

In 1995, Romano Prodi, a former minister of Industry on behalf of the left-wing faction of Christian Democracy (DC), entered politics and founded The Olive Tree (L'Ulivo), a centre-left coalition including the PDS, the Italian People's Party (PPI), the Federation of the Greens (FdV), Italian Renewal (RI), the Italian Socialists (SI) and Democratic Union (UD). The coalition in alliance with the Communist Refoundation Party (PRC) won the 1996 general election and Prodi became Prime Minister.

In February 1998, the PDS merged with minor social-democratic parties (Labour Federation and Social Christians, among others) to become the Democrats of the Left (DS), while in March 2002 the PPI, RI and The Democrats (Prodi's own party, launched in 1999) became Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy (DL). In the summer of 2003, Prodi suggested that centre-left forces should participate in the 2004 European Parliament election with a common list. Whereas the Union of Democrats for Europe (UDEUR) and the far-left parties refused, four parties accepted, namely the DS, DL, the Italian Democratic Socialists (SDI) and the European Republicans Movement (MRE). These launched a joint list named United in the Olive Tree which ran in the election and garnered 31.1% of the vote. The project was later abandoned in 2005 by the SDI.

In the 2006 general election, the list obtained 31.3% of the vote for the Chamber of Deputies.

Road to the Democratic Party

The project of a Democratic Party was often mentioned by Prodi as the natural evolution of The Olive Tree and was bluntly envisioned by Michele Salvati, a former centrist deputy of the DS, in an appeal in Il Foglio newspaper in April 2013.[16] The term Partito Democratico was used for the first time in a formal context by the DL and DS members of the Regional Council of Veneto, who chose to form a joint group named The Olive Tree – Venetian Democratic Party (L'Ulivo – Partito Democratico Veneto) in March 2007.[17]

The 2006 election result, anticipated by the 2005 primary election in which over four million voters endorsed Prodi as candidate for Prime Minister, gave a push to the project of a unified centre-left party. Eight parties agreed to merge into the PD:

- Democrats of the Left (DS, social-democratic, leader: Piero Fassino)

- Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy (DL, centrist, leader: Francesco Rutelli).

- Southern Democratic Party (PDM, centrist, leader: Agazio Loiero);

- Sardinia Project (PS, social-democratic, leader: Renato Soru);

- European Republicans Movement (MRE, social-liberal, leader: Luciana Sbarbati);

- Democratic Republicans (RD, social-liberal, leader: Giuseppe Ossorio);

- Middle Italy (IdM, centrist, leader: Marco Follini);

- Reformist Alliance (AR, social-democratic, leader: Ottaviano Del Turco).

While the DL agreed to the merger with virtually no resistance, the DS experienced a more heated final congress. On 19 April 2007, approximately 75% of party members voted in support of the merger of the DS into the PD. The left-wing opposition, led by Fabio Mussi, obtained just 15% of the support within the party. A third motion, presented by Gavino Angius and supportive of the PD only within the Party of European Socialists (PES), obtained 10% of the vote. Both Mussi and Angius refused to join the PD and, following the congress, founded a new party called Democratic Left (SD).

On 22 May 2007, the organising committee of the nascent party was formed. It consisted of 45 members, mainly politicians from the two aforementioned major parties and the leaders of the other six minor parties. Also leading external figures such as Giuliano Amato, Marcello De Cecco, Gad Lerner, Carlo Petrini and Tullia Zevi were included.[18] On 18 June, the committee decided the rules for the open election of the 2,400 members of the party's constituent assembly; each voter could choose between a number of lists, each of them associated with a candidate for secretary.

Foundation and leadership election

All candidates interested in running for the PD leadership had to be associated with one of the founding parties and present at least 2,000 valid signatures by 30 July 2007. A total of ten candidates officially registered their candidacy: Walter Veltroni, Rosy Bindi, Enrico Letta, Furio Colombo, Marco Pannella, Antonio Di Pietro, Mario Adinolfi, Pier Giorgio Gawronski, Jacopo Schettini, Lucio Cangini and Amerigo Rutigliano. Of these, Pannella and Di Pietro were rejected because of their involvement in external parties (the Radicals and Italy of Values respectively) whereas Cangini and Rutigliano did not manage to present the necessary 2,000 valid signatures for the 9pm deadline and Colombo's candidacy was instead made into hiatus in order to give him 48 additional hours to integrate the required documentation. Colombo later decided to retire his candidacy citing his impossibility to fit with all the requirements.[19] All rejected candidates had the chance against the decision in 48 hours' time,[20] with Pannella and Rutigliano being the only two candidates to appeal against it.[21] Both were rejected on 3 August.[22]

On 14 October 2007, Veltroni was elected leader with about 75% of the national votes in an open primary attended by over three million voters.[23] Veltroni was proclaimed secretary during a party's constituent assembly held in Milan on 28 October 2007.[24]

On 21 November, the new logo was unveiled. It depicts an olive branch and the acronym PD in colours reminiscent of the Italian tricolour flag (green, white and red). In the words of Ermete Realacci, green represents the ecologist and social-liberal cultures, white the Catholic solidarity and red the socialist and social-democratic traditions.[25] The green-white-red idea was coined by Schettini during his campaign.

Leadership of Walter Veltroni

After the premature fall of the Prodi II Cabinet in January 2008, the PD decided to form a less diverse coalition. The party invited the Radicals and the Socialist Party (PS) to join its lists, but only the Radicals accepted and formed an alliance with Italy of Values (IdV) which was set to join the PD after the election. The PD included many notable candidates and new faces in its lists and Walter Veltroni, who tried to present the PD as the party of the renewal in contrast both with Silvio Berlusconi and the previous centre-left government, ran an intense and modern campaign which led him to visit all provinces of Italy, but that was not enough.

In the 2008 general election on 13–14 April 2008, the PD–IdV coalition won 37.5% of the vote and was defeated by the centre-right coalition, composed of The People of Freedom (PdL), the Lega Nord and the Movement for Autonomy (46.8%). The PD was able to absorb some votes from the parties of the far-left as also IdV did, but lost voters to the Union of the Centre (UdC), ending up with 33.2% of the vote, 217 deputies and 119 senators. After the election Veltroni, who was gratified by the result, formed a shadow cabinet. IdV, excited by its 4.4% which made it the fourth largest party in Parliament, refused to join both the Democratic groups and the shadow cabinet.

The early months after the election were a difficult time for the PD and Veltroni, whose leadership was weakened by the growing influence of internal factions because of the popularity of Berlusconi and the dramatic rise of IdV in opinion polls.[26] IdV became a strong competitor of the PD and the relations between the two parties became tense. In the 2008 Abruzzo regional election, the PD was forced to support IdV candidate Carlo Costantini.[27] In October, Veltroni, who distanced from Di Pietro many times, declared that "on some issues he [Di Pietro] is distant from the democratic language of the centre-left".[28]

Leadership of Dario Franceschini

After a crushing defeat in the February 2009 Sardinian regional election, Walter Veltroni resigned as party secretary. His deputy Dario Franceschini took over as interim party secretary to guide the party toward the selection of a new stable leader.[29][30][30] Franceschini was elected by the party's national assembly with 1,047 votes out of 1,258. His only opponent Arturo Parisi won a mere 92 votes.[29][30] Franceschini was the first former Christian Democrat to lead the party.

The 2009 European Parliament election was an important test for the PD. Prior to the election, the PD considered offering hospitality to the Socialist Party (PS) and the Greens in its lists, and proposed a similar pact to Democratic Left (SD).[31] However, the Socialists, the Greens and Democratic Left decided instead to contest the election together as a new alliance called Left and Freedom which failed to achieve the 4% threshold required to return any MEPs, but damaged the PD, which gained 26.1% of the vote, returning 21 MEPs.

Leadership of Pier Luigi Bersani

The national convention and a subsequent open primary were called for October,[32][33] with Franceschini, Pier Luigi Bersani and Ignazio Marino were running for the leadership,[34][35] while a fourth candidate, Rutigliano, was excluded because of lack of signatures.[36] In local conventions, a 56.4% of party members voted and Bersani was by far the most voted candidate with 55.1% of the vote, largely ahead of Franceschini (37.0%) and Marino (7.9%).[37] Three million people participated in the open primary on 25 October 2009; Bersani was elected new secretary of the party with about 53% of the vote, ahead of Franceschini with 34% and Marino with 13%. On 7 November, during the first meeting of the new national assembly, Bersani was declared secretary, Rosy Bindi was elected party president (with Marina Sereni and Ivan Scalfarotto vice-presidents), Enrico Letta deputy secretary and Antonio Misiani treasurer.[38][39]

In reaction to the election of Bersani, perceived by some moderates as an old-style social democrat, Francesco Rutelli (a long-time critic of the party's course) and other centrists and liberals within the PD left in order to form a new centrist party, named Alliance for Italy (ApI).[40] Following March 2009, and especially after Bersani's victory, many deputies,[41] senators,[42] one MEP and several regional/local councillors[43] left the party to join the UdC, ApI and other minor parties. They included many Rutelliani and most Teodems.

In March 2010, a big round of regional elections, involving eleven regions, took place. The PD lost four regions to the centre-right (Piedmont, Lazio, Campania and Calabria), and maintained its hold on six (Liguria, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Marche, Umbria and Basilicata), plus Apulia, a traditionally conservative region where due to divisions within the centre-right Nichi Vendola of SEL was re-elected with the PD's support.

In September 2011, Bersani was invited by Antonio Di Pietro's IdV to take part to its annual late summer convention in Vasto, Abruzzo. Bersani, who had been accused by Di Pietro of avoiding him in order to court the centre-right UdC,[44] proposed the formation of a New Olive Tree coalition comprising the PD, IdV and SEL.[45] The three party leaders agreed in what was soon dubbed the pact of Vasto.[46][47] However, after the resignation of Silvio Berlusconi as Prime Minister in November 2011 the PD gave external support to Mario Monti's technocratic government, along with the PdL and the UdC,[48][49] effectively broking with IdV and SEL.

Road to the 2013 general election

A year after the pact of Vasto, the relations between the PD and IdV had become tense. IdV and its leader, Antonio Di Pietro, were thus excluded from the coalition talks led by Bersani. To these talks were instead invited SEL led by Nichi Vendola and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) led by Riccardo Nencini. The talks resulted on 13 October 2012 in the Pact of Democrats and Progressives (later known as Italy. Common Good) and produced the rules for the upcoming centre-left primary election, during which the PD–SEL–PSI joint candidate for Prime Minister in the 2013 general election would be selected.[50][51]

In the primary, the strongest challenge to Bersani was posed by a fellow Democrat, the 37-year-old mayor of Florence Matteo Renzi, a liberal moderniser, who had officially launched his leadership bid on 13 September 2012 in Verona, Veneto.[52] Bersani launched his own bid on 14 October in his hometown Bettola, north-western Emilia.[53][54][55] Other candidates included Nichi Vendola (SEL),[56] Bruno Tabacci (ApI) and Laura Puppato (PD).[57]

In the 2012 regional election, Rosario Crocetta (member of the PD) was elected President with 30.5% of the vote thanks to the support of the UdC, but the coalition failed to secure an outright majority in the Regional Assembly.[58][59] For the first time in 50 years, a man of the left had the chance to govern Sicily.

On 25 November, Bersani came ahead in the first round of the primary election with 44.9% of the vote, Renzi came second with 35.5%, followed by Vendola (15.6%), Puppato (2.6%) and Tabacci (1.4%). Bersani did better in the South while Renzi prevailed in Tuscany, Umbria and Marche.[60] In the subsequent run-off, on 2 December, Bersani trounced Renzi 60.9% to 39.1% by winning in each and every single region but Tuscany, where Renzi won 54.9% of the vote. The PD secretary did particularly well in Lazio (67.8%), Campania (69.4%), Apulia (71.4%), Basilicata (71.7%), Calabria (74.4%), Sicily (66.5%) and Sardinia (73.5%).[61]

2013 general election

In the election, the PD and its coalition fared much worse than expected and according to pollsters predictions. The PD won just 25.4% of the vote for the Chamber of Deputies (–8.0% from 2008) and the centre-left coalition narrowly won the majority in the house over the centre-right coalition (29.5% to 29.3%). Even worse, in the Senate the PD and its allies failed to get an outright majority due to the rise of the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the centre-right's victory in key regions such as Lombardy, Veneto, Campania, Apulia, Calabria and Sicily (the centre-right was awarded of the majority premium in those regions, leaving the centre-left with just a handful of elects there). Consequently, the PD-led coalition was unable to govern alone because it lacked a majority in the Senate which has equal power to the Chamber. As a result, Bersani, who refused any agreement with the PdL and was rejected by the M5S, failed to form a government.

After an agreement with the centre-right parties, Bersani put forward Franco Marini as his party's candidate for President to succeed to Giorgio Napolitano on 17 April. However, Renzi, several Democratic delegates and SEL did not support Marini.[62] On 18 April, Marini received just 521 votes in the first ballot, short of the 672 needed,[63] as more than 200 centre-left delegates rebelled. On 19 April, the PD and SEL selected Romano Prodi to be their candidate in the fourth ballot.[64] Despite his candidacy had received unanimous support among the two parties' delegates, Prodi obtained only 395 votes in the fourth ballot[63] as more than 100 centre-left electors did not vote for him.[65] After the vote, Prodi pulled out of the race and Bersani resigned as party secretary.[66] Bindi, the party's president, also resigned. The day after Napolitano accepted to stand again for election and was re-elected President with the support of most parliamentary parties.

On 28 April, Enrico Letta, the party's deputy secretary and former Christian Democrat, was sworn in as Prime Minister of Italy at the head of a government based around a grand coalition including the PdL, Civic Choice (SC) and the UdC. Letta was the first Democrat to become Prime Minister.

Leadership of Guglielmo Epifani

After Bersani's resignation from party secretary on 20 April 2013, the PD remained without a leader for two weeks. On 11 May 2013, Guglielmo Epifani was elected secretary at the national assembly of the party with 85.8% of vote. Epifani, secretary-general of the Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGIL), Italy's largest trade union, from 2002 to 2010, was the first former Socialist to lead the party. Epifani's mission was to lead the party toward a national convention in October.[67]

A few weeks after Epifani's election as secretary, the PD had a success in the 2013 local elections, winning in 69 comuni (including Rome and all the other 14 provincial capitals up for election) while the PdL won 22 and the M5S 1.[68]

The decision, on 9 November, that the PD would organise the next congress of the Party of European Socialists (PES) in Rome in early 2014, sparked protests among some of the party's Christian democrats, who opposed PES membership.[69]

Epifani was little more than a secretary pro tempore and in fact frequently repeated that he was not going to run for a full term as secretary in the leadership race that would take place in late 2013, saying that his candidacy would be a betrayal of his mandate.[70][71][72][73]

Leadership of Matteo Renzi

Four individuals filed their bid for becoming secretary, namely Matteo Renzi, Pippo Civati, Gianni Cuperlo and Gianni Pittella.[74] The leadership race started with voting by party members in local conventions (7–17 November). Renzi came first with 45.3%, followed by Cuperlo (39.4%), Civati (9.4%) and Pittella (5.8%).[75] The first three were admitted to the open primary.

On 8 December, Renzi, who won in all regions but was stronger in the Centre-North, trounced his opponents with 67.6% of the vote. Cuperlo, whose support was higher in the South, came second with 18.2% while Civati, whose message did well with northern urban and progressive voters, came third with 14.2%.[76] On 15 December, Renzi, whose executive included many young people and a majority of women,[77] was proclaimed secretary by the party's national assembly while Cuperlo was elected president as proposed by Renzi.[78]

On 20 January 2014, Cuperlo criticized the electoral reform proposed by Renzi in agreement with Berlusconi, but the proposal was overwhelmingly approved by the party's national board.[79] The day after the vote, Cuperlo resigned from president.[80] He was later replaced by Matteo Orfini, who hailed from the party's left-wing, but since then became more and more supportive of Renzi.

After frequent calls by Renzi for a new phase, the national board decided to put an end to Letta's government on 13 February and form a new one led by Renzi as the latter had proposed.[81][82] Subsequently, Renzi was sworn in as Prime Minister on 22 February at the head of an identical coalition.[83] On 28 February, the PD officially joined the PES as a full member,[84] ending a decade-long debate.

Premiership of Matteo Renzi

In the 2014 European Parliament election, the party obtained 40.8% of the vote and 31 seats. The party's score was virtually 15 percentage points up from five years before and the best result for an Italian party in a nationwide election since the 1958 general election, when Christian Democracy won 42.4%. The PD was also the largest national party within the Parliament in its 8th term.[85] Following his party's success, Renzi was able to secure the post of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy within the European Commission for Federica Mogherini, his minister of Foreign Affairs.[86]

In January 2015, Sergio Mattarella, a veteran left-wing Christian Democrat and founding member of the PD, whose candidacy had been proposed by Renzi and unanimously endorsed by the party's delegates, was elected President of Italy during a presidential election triggered by President Giorgio Napolitano's resignation.

During Renzi's first year as Prime Minister, several MPs defected from other parties to join the PD. They comprised splinters from SEL (most of whom led by Gennaro Migliore, see Freedom and Rights), SC (notably including Stefania Giannini, Pietro Ichino and Andrea Romano) and the M5S. Consequently, the party increased its parliamentary numbers to 311 deputies and 114 senators by April 2015.[87][88] Otherwise, Sergio Cofferati,[89] Giuseppe Civati[90] and Stefano Fassina[91] left. They were the first and most notable splinters among the ranks of the party's internal left, but several others followed either Civati (who launched Possible) or Fassina (who launched Future to the Left and Italian Left) in the following months.[92] By May 2016, the PD's parliamentary numbers had gone down to 303 deputies and 114 senators.[87][88]

In the 2015 regional elections, Democratic Presidents were elected (or re-elected) in five regions out of seven, namely Enrico Rossi in Tuscany, Luca Ceriscioli in Marche, Catiuscia Marini in Umbria, Vincenzo De Luca in Campania and Michele Emiliano in Apulia. As a result, 16 regions out of 20, including all those of central and southern Italy, were governed by the centre-left while the opposition Lega Nord led Veneto and Lombardy and propped up a centre-right government in Liguria.

Road to the 2018 general election

After a huge defeat in the 2016 constitutional referendum (59.9% no, 40.1% yes), Renzi resigned as Prime Minister in December 2016 and was replaced by fellow Democrat Paolo Gentiloni, whose government's composition and coalition were very similar to those of the Renzi Cabinet. In February 2017, Renzi resigned also as PD secretary in order to run in the 2017 leadership election.[93][94][95][96][97] Renzi, Andrea Orlando (one of the leaders of the Remake Italy faction; the other leader Matteo Orfini was the party's president and supported Renzi) and Michele Emiliano were the three contenders for the party's leadership.[98]

Subsequently, a substantial group of leftists (24 deputies, 14 senators and 3 MEPs), led by Enrico Rossi (Democratic Socialists) and Roberto Speranza (Reformist Area), backed by Massimo D'Alema, Pier Luigi Bersani and Guglielmo Epifani, left the PD and formed Article 1 – Democratic and Progressive Movement (MDP), along with splinters from the Italian Left (SI) led by Arturo Scotto.[99][100][101][102][103] Most of the splinters as well as Scotto were former Democrats of the Left. In December 2017, the MDP, SI and Possible would launch Free and Equal (LeU) under the leadership of the President of the Senate Pietro Grasso[104][105] (another PD splinter).[106][107][108]

In local conventions, Renzi came first (66.7%), Orlando second (25.3%) and Emiliano third (8.0%). In the open primary on 30 April, Renzi won 69.2% of the vote as opposed to Orlando's 20.0% and Emiliano's 10.9%.[109][110] On 7 May, Renzi was sworn in as secretary again, with Maurizio Martina as deputy and Orfini was confirmed president.

In the 2017 Sicilian regional election Crocetta did not stand and the PD-led coalition was defeated.

In the run-up of the 2018 general election, the PD tried to form a broad centre-left coalition, but only minor parties showed interest. As a result, the alliance comprised Together (a list notably including the Italian Socialist Party and the Federation of the Greens), the Popular Civic List (notably including Popular Alternative, Italy of Values, the Centrists for Europe and Solidary Democracy) and More Europe (including the Italian Radicals, Forza Europa and the Democratic Centre).

2018 general election

In the election, the PD obtained its worst result ever: 18.7% of the vote, well behind the M5S (32.7%) and narrowly ahead of the Lega (17.4%). Following his party's defeat, Renzi resigned from secretary[111] and his deputy Martina started functioning as acting secretary.

After two months of negotiations and the refusal of the PD to join forces with the M5S,[112] the latter and the Lega formed a government under Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, a M5S-proposed independent. Thus, the party returned to opposition after virtually seven years and experienced some internal turmoil as its internal factions started to re-position themselves in the new context. Both Gentiloni and Franceschini distanced from Renzi[113] while Carlo Calenda, a former minister in Renzi's and Gentiloni's governments who had joined the party soon after the election,[114] proposed to merge the PD into a larger republican front.[115][116] However, according to several observers Renzi's grip over the party was still strong and he was still the PD's leader behind the scenes.[117][118]

Leadership of Maurizio Martina

In July, Maurizio Martina was elected secretary by the party's national assembly and a new leadership election was scheduled for the first semester of 2019.[119] On 17 November 2018, Martina resigned and the national assembly was dissolved, starting the electoral proceedings.[120]

During Martina's tenure, especially after a rally in Rome in September,[121] the party started to prepare for the leadership election.

In January 2019, Calenda launched the "We Are Europeans" manifesto advocating for a pro-European joint list at the upcoming European Parliament election.[122] Among those who signed there were several Democratic regional presidents and mayors as well as Giuseppe Sala and Giuliano Pisapia, two independents who are the current mayor of Milan and his predecessor, respectively.[123] Calenda aimed at uniting the PD, More Europe and the Greens–Italy in Common.[124][125]

Leadership of Nicola Zingaretti

Three major candidates, Martina, Nicola Zingaretti and Roberto Giachetti, plus a handful of minor ones, formally filed papers in order to run for secretary. Prior to that, Marco Minniti, minister of the Interior in the Gentiloni Cabinet, had also launched his bid,[126][127] before renouncing in December[128][129] and supporting Zingaretti.[130] Zingaretti won the first round by receiving 47.4% of the vote among party members in local conventions. He, along with Martina and Giachetti, qualified for the primary election, to be held on 3 March. In the event, Zingaretti was elected secretary, exceeding expectations and winning 66.0% of the vote while Martina and Giachetti won 22.0% and 12.0%, respectively.[131][132]

Zingaretti was officially appointed by the national assembly, on 17 March.[133] On the same day, former Prime Minister Gentiloni was elected as the party's new president.[134] A month later, Zingaretti appointed Andrea Orlando and Paola De Micheli as deputy secretaries.[135]

In the run-up to the 2019 European Parliament election Zingaretti presented a special logo including a large reference to "We Are Europeans" and the symbol of the PES.[7] Additionally, the party forged an alliance with Article One.[136] In the election, the PD garnered 22.7% of the vote, finishing second after the League.[137] Calenda was the most voted candidate of the party.[138]

On 3 July 2019 David Sassoli, a member of the PD, was elected President of the European Parliament.[139]

Coalition with the Five Star Movement

In August 2019 tensions grew within Conte's government coalition, leading to the issuing of a motion of no-confidence on Prime Minister Conte by the League.[140] After Conte's resignation, the national board of the PD officially opened to the possibility of forming a new cabinet in a coalition with the M5S,[141] based on pro-Europeanism, green economy, sustainable development, fight against economic inequality and a new immigration policy.[142] The party also accepted that Conte may continue at the head of a new government,[143] and on 29 August President Mattarella formally invested Conte to do so.[144] Disappointed by the party's decision to form a government with the M5S, Calenda decided to leave and establish We Are Europeans as an independent party.[145]

The Conte II Cabinet took office on 5 September, with Franceschini as Minister of Culture and head of the PD's delegation.[146] Gentiloni was contextually picked by the government as the Italian member of the von der Leyen Commission[147] and would serve as European Commissioner for the Economy.[148]

On 18 September, Renzi, who had been one of the earliest supporters of a M5S–PD pact in August,[149] left the PD and established a new centrist party named Italia Viva (IV).[150] 24 deputies and 13 senators (including Renzi) left.[151] However, not all supporters of Renzi followed him in the split: while the Always Forward and Back to the Future factions mostly followed him, most members of Reformist Base remained in the party.[152] Other MPs and one MEP joined IV afterwards.

From 15 to 17 November, the party held a three-days convention in Bologna, named Tutta un'altra storia ("A whole different story"), with the aim of presenting party's proposals for the 2020s decade.[153] The convention was characterized by a strong leftward move, stressing a strong distance from liberal and centrist policies promoted under Renzi's leadership.[154][155] Some newspapers, like La Stampa, compared Zingaretti's new policies to Jeremy Corbyn's.[156] On 17 November the party's national assembly approved the new party's statute, featuring the separation between the roles of party secretary and candidate for Prime Minister.[157]

Starting from November 2019, the grassroots Sardines movement began in the region of Emilia-Romagna, aimed at contrasting the rise of right-wing populism and the League in the region. The movement endorsed the PD's candidate Stefano Bonaccini in the upcoming Emilia-Romagna regional election.[158] In the next months the movement grew to a national level. On 26 January Bonaccini was re-elected wuth 51.4% of the vote. On the same day, in the Calabrian regional election, the centre-left candidate supported by the PD lost to the centre-right candidate Jole Santelli, who won with 55.3% of the vote.[159]

On 22 February 2020 the national assembly of the PD unanimously elected its new president, Valentina Cuppi, mayor of Marzabotto.[11]

Ideology

The PD is a big tent centre-left party, influenced by the ideas of social democracy and Christian left. The common roots of the founding components of the party reside in the Italian resistance movement, the writing of Italian Constitution and the Historic Compromise, all three events which saw the Italian Communist Party and Christian Democracy (the two major forerunners of the Democrats of the Left and Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy, respectively) cooperate. The United States Democratic Party and American liberalism are also important sources of inspiration.[160][161][162][163] In a 2008 interview to El País, Veltroni, who can be considered the main founding father of the party, clearly stated that the PD should be considered a reformist party and could not be linked to the traditional values of the left-wing.[164]

There is also a debate on whether the PD is actually a social-democratic party and to what extent. For instance, Alfred Pfaller observed that the PD "has adopted a pronounced centrist-pragmatic position, trying to appeal to a broad spectrum of middle-class and working-class voters, but shying away from a determined pursuit of redistributive goals".[165] For his part, Gianfranco Pasquino observed that "for almost all the leaders, militants and members of the PD, social democracy has never been part of their past nor should represent their political goal", but he also concluded that "its overall identity and perception are by no means those of an European-style social-democratic party".[3]

The party stresses national and social cohesion, progressivism, a moderate social liberalism, green issues, progressive taxation and pro-Europeanism. In this respect, the party's precursors strongly supported the need of balancing budgets in order to comply to Maastricht criteria. Under Veltroni and more recently Renzi, the party took a strong stance in favour of constitutional reform and of a new electoral law on the road toward a two-party system.

While traditionally supporting the social integration of immigrants, the PD has adopted a more critical approach on the issue since 2017.[166] Inspired by Renzi, re-elected secretary in April; and Marco Minniti, interior minister since December 2016, the party promoted stricter policies regarding immigration and public security.[167][168] These policies resulted in broad criticism from the left-wing Democrats and Progressives (partners in government) as well as left-leaning intellectuals like Roberto Saviano and Gad Lerner.[169] In August, Lerner, who was among the founding members of the PD, left the party altogether due to its new immigration policies.[170]

Ideological trends

The PD is a plural party, including several distinct ideological trends:[171]

- Social democracy. The bulk of the party, including many former Democrats of the Left, is social-democratic and emphasizes labour and social issues. There are traditional social democrats (Nicola Zingaretti and his Great Square faction, Andrea Orlando and his Democracy Europe Society faction, Maurizio Martina and his Side by Side faction, Gianni Cuperlo and LeftDem, as well as many other people and factions; prior to the February 2017 split, it also included Massimo D'Alema, Pier Luigi Bersani, Enrico Rossi and Roberto Speranza), and Third Way types (Walter Veltroni, Piero Fassino and Debora Serracchiani, among others). While the former are supportive of democratic socialism, the latter are strongly influenced by American liberalism and New Labour ideas.

- Christian left. The party includes many Christian-inspired members, most of whom come from the left-wing of the late Christian Democracy (having later joined Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy). Democratic Catholics have been affiliated to several factions, including Luca Lotti's Reformist Base, Dario Franceschini's AreaDem (which includes also some leading Third-Way social democrats as the aforementioned Fassino and Serracchiani), Enrico Letta's 360 Association (also Lettiani, mainly Christian democrats and centrists), Giuseppe Fioroni's Populars, Rosy Bindi's Democrats Really and the Social Christians (who adhere to Christian socialism).

- Social liberalism. It is endorsed by former members of the Italian Republican Party, the Italian Liberal Party and the Radical Party, and notably the Liberal PD faction.

- Green politics. It is endorsed mainly by former members of the Federation of the Greens and other greens, who have jointly formed the Democratic Ecologists.

It is not an easy task to include the trend represented by Matteo Renzi, whose supporters have been known as Big Bangers, Now!, or more frequently Renziani, in any of the categories above. The nature of Renzi's progressivism is a matter of debate and has been linked both to liberalism and populism.[172][172][173][174][175][176] According to Maria Teresa Meli of Corriere della Sera, Renzi "pursues a precise model, borrowed from the Labour Party and Bill Clinton's Democratic Party", comprising "a strange mix (for Italy) of liberal policies in the economic sphere and populism. This means that, on one side, he will attack the privileges of trade unions, especially of the CGIL, which defends only the already protected, while, on the other, he will sharply attack the vested powers, bankers, Confindustria and a certain type of capitalism [...]".[177] After Renzi led some of his followers out of the party and launched the alternative Italia Viva party, a good chunk of Renziani (especially those affiliated to Reformist Base and Liberal PD) remained in the PD. Other leading former Renziani notably include Lorenzo Guerini, Graziano Delrio (party leader in the Chamber) and Andrea Marcucci (party leader in the Senate).

International affiliation

International affiliation was quite a controversial issue for the PD in its early days and it was settled only in 2014.

.jpg)

The debate on which European political party to join saw the former Democrats of the Left generally in favour of the Party of European Socialists (PES) and most former members of Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy in favour of the European Democratic Party (EDP), a component of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) Group. After the party's formation in 2007, the new party's MEPs continued to sit with the PES and ALDE groups to which their former parties had been elected during the 2004 European Parliament election. Following the 2009 European Parliament election, the party's 21 MEPs chose to unite for the new term within the European parliamentary group of the PES, which was renamed the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D).[178]

On 15 December 2012, PD leader Pier Luigi Bersani attended in Rome the founding convention of the Progressive Alliance (PA), a nascent political international for parties dissatisfied with the continued admittance and inclusion of authoritarian movements into the Socialist International (SI).[179][180] On 22 May 2013, the PD was a founding member of the PA at the international's official inauguration in Leipzig, Germany on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the formation of the General German Workers' Association, the oldest of the two parties which merged in 1875 in order to form the Social Democratic Party of Germany.[181]

Matteo Renzi, a centrist who led the party in 2013–2018, wanted the party to join both the SI and the PES.[182][183][184] On 20 February 2014, the PD leadership applied for full membership of the PES.[185][186] In Renzi's view, the party would count more as a member of a major European party and within the PES it would join forces with alike parties such as the British Labour Party. On 28 February, the PD was welcomed as a full member into the PES.[84]

Factions

The PD includes several internal factions, most of which trace the previous allegiances of party members. Factions form different alliances depending on the issues and some party members have multiple factional allegiances.

2007 leadership election

After the election, which saw the victory of Walter Veltroni, the party's internal composition was as follows:

- Majority led by Walter Veltroni (75.8%)

- Three national lists supported the candidacy of Veltroni. The bulk of the former Democrats of the Left (Veltroniani, Dalemiani, Fassiniani), the Rutelliani of Francesco Rutelli (including the Teodems), The Populars of Franco Marini, Liberal PD, the Social Christians and smaller groups (Middle Italy, European Republicans Movement, Reformist Alliance and the Reformists for Europe) formed a joint-list named Democrats with Veltroni (43.7%). The Democratic Ecologists of Ermete Realacci, together with Giovanna Melandri and Cesare Damiano, formed Environment, Innovation and Labour (8.1%). The Democrats, Laicists, Socialists, Say Left and the Labourites – Liberal Socialists presented a list named To the Left (7.7%). Local lists in support of Veltroni got 16.4%.

- Minorities led by Rosy Bindi (12.9%) and Enrico Letta (11.0%)

- The Olivists, whose members were staunch supporters of Romano Prodi, divided in two camps. The largest one, including Arturo Parisi, endorsed Rosy Bindi while a smaller one, including Paolo De Castro, endorsed Enrico Letta. Bindi benefited also from the support of Agazio Loiero's Southern Democratic Party while Letta was endorsed by Lorenzo Dellai's Daisy Civic List, Renato Soru's Sardinia Project and Gianni Pittella's group of social democrats.

2009 leadership election

After the election, which saw the victory of Pier Luigi Bersani, the party's internal composition was as follows:

- Majority led by Pier Luigi Bersani (53.2%)

- Bersaniani and Dalemiani: the social-democratic groups around Bersani and Massimo D'Alema (who wants the PD to be a traditional centre-left party in the European social-democratic tradition). D'Alema organized his faction as Reformists and Democrats, welcoming also some Lettiani and some Populars.

- Lettiani: the centrist group around Enrico Letta, known also as 360 Association. Its members were keen supporters of an alliance with the Union of the Centre.

- To the Left: the social-democratic and democratic-socialist internal left led by Livia Turco.

- Democrats Really: the group around Rosy Bindi and composed mainly of the left-wing members of the late Italian People's Party.

- Social Christians: a Christian social-democratic group that was a founding component of the Democrats of the Left.

- Democracy and Socialism: a social-democratic group of splinters from the Socialist Party led by Gavino Angius.

- AreaDem, minority led by Dario Franceschini (34.3%).

- Veltroniani: followers of Walter Veltroni and social democrats coming from the Democrats of the Left who support the so-called "majoritarian vocation" of the party, the selection of party candidates and leaders through primaries and a two-party system.

- Populars/Fourth Phase: heirs of the Christian left tradition of the Italian People's Party and of the left wing of the late Christian Democracy.

- Rutelliani: centrists and liberals gathered around Francesco Rutelli, known also as Free Democrats; most of them left after Bersani's victory to form the Alliance for Italy while a minority (Paolo Gentiloni and Ermete Realacci, among others) chose to stay.

- Simply Democrats: a list promoted by a diverse group of leading Democrats (Debora Serracchiani, Rita Borsellino, Sergio Cofferati, David Sassoli and Francesca Barracciu) who were committed to renewal in party leadership and cleanliness of party elects.

- Liberal PD: the liberal (mostly social-liberal) faction of the PD led by Valerio Zanone. Its members have been close to Veltroni and Rutelli.

- Democratic Ecologists: the green faction of the PD led by Ermete Realacci. Its members have been close to Veltroni and Rutelli.

- Teodem: a tiny Christian-democratic group representing the right-wing of the party on social issues, albeit being progressive on economic ones. Most Teodems, including their leader Paola Binetti, left the PD in 2009–2010 in order to join the UdC or the ApI while others, led by Luigi Bobba, chose to stay.

- Minority led by Ignazio Marino (12.5%)

- Un-affiliated social liberals, social democrats and supporters of a broad alliance including Italy of Values, the Radicals and the parties to the left of the PD. After the election, most of them joined Marino in an association named Change Italy.

- Democrats in Network: a social-democratic faction of former Veltroniani led by Goffredo Bettini.

- Non-aligned factions

- Olivists: followers of Romano Prodi who want the party to be stuck in the tradition of The Olive Tree. The group was led by Arturo Parisi and includes both Christian left exponents and social democrats. Most Olivists supported Bersani while Parisi endorsed Franceschini.

2010–2013 developments

In the summer of 2010, Dario Franceschini, leader of AreaDem (the largest minority faction) and Piero Fassino re-approached with Pier Luigi Bersani and joined the party majority.[187] As a response, Walter Veltroni formed Democratic Movement to defend the "original spirit" of the PD.[187] In doing this he was supported by 75 deputies: 33 Veltroniani, 35 Populars close to Giuseppe Fioroni and 7 former Rutelliani led by Paolo Gentiloni.[188][189][190] Some pundits hinted that the Bersani-Franceschini pact was envisioned in order both to marginalise Veltroni and to reduce the influence of Massimo D'Alema, the party bigwig behind Bersani, whose 2009 bid was supported primarily by Dalemiani. Veltroni and D'Alema had been long-time rivals within the centre-left.[191]

As of September the party's majority was composed of those who supported Bersani since the beginning (divided in five main factions: Bersaniani, Dalemiani, Lettiani, Bindiani and the party's left-wing) and AreaDem of Franceschini and Fassino. There were also two minority coalitions, namely Veltroni's Democratic Movement (Veltroniani, Fioroni's Populars, ex-Rutelliani, Democratic Ecologists and a majority of Liberal PD members) and Change Italy of Ignazio Marino.[192]

According to Corriere della Sera in November 2011, the party was divided mainly in three ideological camps battling for its soul:

- a socialist left: the Young Turks (mostly supporters of Bersani such as Stefano Fassina and Matteo Orfini);

- a social-democratic centre: it includes Bersani's core supporters (Bersaniani, Dalemiani and Bindiani); and

- a "new right": Matteo Renzi's faction, proposing an overtly liberal political line.[193][194]

Since November 2011, similar differences surfaced in the party over Monti Cabinet. While the party's right-wing, especially Liberal PD, was enthusiastic in its support, Fassina and other leftists, especially those linked to trade unions, were critical.[195][196][197][198] In February 2012, Fassina published a book in which he described his view as "neo-labourite humanism" and explained it in connection with Catholic social teaching, saying that his "neo-labourism" was designed to attract Catholic voters.[199] Once again, his opposition to economic liberalism was strongly criticized by the party's right-wing as well as by Stefano Ceccanti, a leading Catholic in the party and supporter of Tony Blair's New Labour, who said that a leftist platform à la Fassina would never win back the Catholic vote in places like Veneto.[200]

According to YouTrend, a website, 35% of the Democratic deputies and senators elected in the 2013 general election were Bersaniani, 23% members of AreaDem (or Democratic Movement), 13% Renziani, 6% Lettiani, 4.5% Dalemiani, 4.5% Young Turks/Remake Italy, 2% Bindiani and 1.5% Civatiani.[201]

As the party performed below expectations, more Democrats started to look at Renzi, who had been defeated by Bersani in the 2012 primary election to select the centre-left's candidate for Prime Minister.[202] In early September, two leading centrists, namely Franceschini and Fioroni (leaders of Democratic Area and The Populars), endorsed Renzi.[203] Two former leaders of the Democrats of the Left, Veltroni and Fassino,[204] also decided to support Renzi while a third, D'Alema, endorsed Gianni Cuperlo.[205]

In October, four candidates filed their bid to become secretary, namey Renzi, Cuperlo, Pippo Civati and Gianni Pittella.[74]

2013 leadership election

After the election, which saw the victory of Matteo Renzi, the party's internal composition was as follows:

- Majority led by Matteo Renzi (67.6%)

- Minority led by Gianni Cuperlo (18.2%):

- Minority led by Pippo Civati (14.2%):

- Civatiani, Laura Puppato[216] and Felice Casson[216]

2014–2016 alignments

After 2013 leadership election, the party's main factions[217][218][219] were the following:

- Renziani: the group around Matteo Renzi, PD leader and Prime Minister as well as a liberal, Third Way-oriented and modernising faction. Renziani supported a two-party system and the so-called "majoritarian vocation" of the PD through the formation of a "party of the nation".[220] Prominent members of the faction were Luca Lotti, Maria Elena Boschi, Graziano Delrio, Lorenzo Guerini, Paolo Gentiloni and Stefano Bonaccini. The faction had a Christian-democratic section called Democratic Space which was led by Delrio and Guerini. Another group of Christian democrats, namely The Populars of Giuseppe Fioroni, were also affiliated. According to news sources as of December 2016, full-fledged Renziani counted 50 MPs, The Populars 30 and other Renziani 25, for a total of 105.

- AreaDem: a mainly Christian leftist faction, with roots in Christian Democracy's left-wing and the Italian People's Party. Led by Dario Franceschini, it notably included Luigi Zanda and Ettore Rosato as well as prominent social democrats like Piero Fassino and Debora Serracchiani, for a total of 90 MPs.

- Left is Change: social-democratic faction led by Maurizio Martina. Most of its members were affiliated with Reformist Area (see below), but splintered in order to support Renzi. The faction which included Cesare Damiano, Vannino Chiti and Anna Finocchiaro, among others, counted 70 MPs.

- Remake Italy: a social-democratic faction loyal to Renzi. Led by Matteo Orfini (the party's president) and Andrea Orlando, it counted 60 MPs.

- Reformist Area/Left: inspired by traditional social democracy and democratic socialism, it was the main left-wing of the party. It was formed by the majority of Bersaniani, loyalists of former secretary Pier Luigi Bersani. The faction's leader was Roberto Speranza. The Reformists often opposed Renzi's policies.[221] Other than Speranza and Bersani, the faction notably included Guglielmo Epifani and Rosy Bindi (whose sub-faction was named Democrats Really) and counted 60 MPs.

- LeftDem: led by Gianni Cuperlo, it was another minority social-democratic faction, including 15 MPs.

2017 leadership election

After the election which saw the victory of Matteo Renzi, the party's internal composition was as follows:

- Majority led by Matteo Renzi (69.2%)

- Renziani; AreaDem;[222] The Populars;[223] a majority of Left is Change (e.g. leader Maurizio Martina,[224] who would serve as deputy secretary if Renzi were to win);[225][226] a minority of Remake Italy (e.g. Matteo Orfini); Liberal PD; and several former Lettiani (e.g. Paola De Micheli)[227]

- Minority led by Andrea Orlando (20.0%)

- A majority of Remake Italy (e.g. Roberto Gualtieri); a minority of Left is Change (e.g. Cesare Damiano and Anna Finocchiaro);[224][228] LeftDem;[229] NetworkDem;[230] several former leading Veltroniani (e.g. Nicola Zingaretti),[231] Lettiani (e.g. Alessia Mosca), Bindiani (e.g. Margherita Miotto) and Olivists (e.g. Sandra Zampa)[232]

- Minority led by Michele Emiliano (10.9%)

- Democratic Front, formed by several PD members in the South, especially Apulia (of which Emiliano is President); some former Lettiani (e.g. Francesco Boccia)[233]

2019 leadership election

After the election which saw the victory of Nicola Zingaretti, the party's internal composition was as follows:[234]

- Majority led by Nicola Zingaretti[235] (66.0%)

- Great Square, Paolo Gentiloni,[236] AreaDem (Dario Franceschini's Franceschiniani and Piero Fassino, among others),[237] Democracy Europe Society,[238] Dem Labourites (Damiano's faction), Socialists and Democrats, LeftDem, NetworkDem and Democratic Front (Michele Emiliano)

- Minority led by Maurizio Martina[235] (22.0%)

- Future! European Democrats (Martina's faction), Harambee (Matteo Richetti), Left Wing (Matteo Orfini) and some Renziani (e.g. Graziano Delrio)

- Minority led by Roberto Giachetti[235] (12.0%)

- Some Renziani (e.g. Maria Elena Boschi), The Populars (Giuseppe Fioroni), Liberal PD, Social Christians and Democratic Ecologists

After the leadership election, supporters of Martina divided in two camps: the liberal and centrist wing close to Renzi (including Lorenzo Guerini and Luca Lotti) formed Reformist Base, while social-democrats (including Martina, Tommaso Nannicini and Debora Serracchiani), as well as some leading centirsts (Delrio and Richetti) formed Side by Side. Additionally, hard-core Renziani, led by Giachetti, formed Always Forward. Others, led by Ettore Rosato, formed Back to the Future.[239]

Full list

Popular support

As previously the Italian Communist Party (PCI), the PD has its strongholds in Central Italy and big cities.

The party governs six regions out of twenty and the cities of Milan, Bologna, Florence and Bari. It also takes part to the government of several other cities, including Padua and Palermo.

In the 2008 and 2013 general elections, the PD obtained its best results in Tuscany (46.8% and 37.5%), Emilia-Romagna (45.7% and 37.0%), Umbria (44.4% and 32.1%), Marche (41.4% and 27.7%), Liguria (37.6% and 27.7%) and Lazio (36.8% and 25.7%). Democrats are generally stronger in the North than the South, with the sole exception of Basilicata (38.6% in 2008 and 25.7% in 2013),[240] where the party has drawn most of its personnel from Christian Democracy (DC).[241]

The 2014 European Parliament election gave a thumping 40.8% of the vote to the party which was the first Italian party to get more than 40% of the vote in a nationwide election since DC won 42.4% of the vote in the 1958 general election. In 2014, the PD did better in Tuscany (56.6%), Emilia-Romagna (52.5%) and Umbria (49.2%), but made significant gains in Lombardy (40.3%, +19.0% from 2009), Veneto (37.5%, +17.2%) and the South.

The 2018 general election was a major defeat for the party as it was reduced to 18.7% (Tuscany 29.6%).

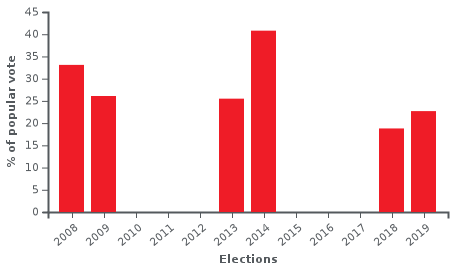

The electoral results of the PD in general (Chamber of Deputies) and European Parliament elections since 2008 are shown in the chart below.

The electoral results of the PD in the 10 most populated regions of Italy are shown in the table below and in the chart electoral results in Italy are shown.

| 2008 general | 2009 European | 2010 regional | 2013 general | 2014 European | 2015 regional | 2018 general | 2019 European | 2020 regional | |

| Piedmont | 32.4 | 24.7 | 23.2 | 25.1 | 40.8 | 41.0[lower-alpha 1] (2014) | 20.5 | 23.9 | - |

| Lombardy | 28.1 | 21.3 | 22.9 | 25.6 | 40.3 | 32.4[lower-alpha 2] (2013) | 21.1 | 23.1 | 22.3[lower-alpha 3] (2018) |

| Veneto | 26.5 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 21.3 | 37.5 | 20.5[lower-alpha 4] | 16.7 | 18.9 | - |

| Emilia-Romagna | 45.7 | 38.6 | 40.6 | 37.0 | 52.5 | 44.5 (2014) | 26.4 | 31.2 | 34.7 |

| Tuscany | 46.8 | 38.7 | 42.2 | 37.5 | 56.6 | 46.3 | 29.6 | 33.3 | - |

| Lazio | 36.8 | 28.1 | 26.3 | 25.7 | 39.2 | 34.2[lower-alpha 5] (2013) | 18.7 | 23.8 | 25.5[lower-alpha 6] (2018) |

| Campania | 29.2 | 23.4 | 21.4 | 21.9 | 36.1 | 29.2[lower-alpha 7] | 13.2 | 19.1 | - |

| Apulia | 30.1 | 21.7 | 20.8 | 18.5 | 33.6 | 32.1[lower-alpha 8] | 13.7 | 16.6 | - |

| Calabria | 32.6 | 25.4 | 22.8[lower-alpha 9] | 22.4 | 35.8 | 36.2[lower-alpha 10] (2014) | 14.3 | 18.3 | - |

| Sicily | 25.4 | 21.9 | 18.8 (2008) | 18.6 | 34.9 | 21.2[lower-alpha 11] (2017) | 11.5 | 16.6 | - |

- Combined result of the PD (36.2%) and Sergio Chiamparino's personal list (4.8%).

- Combined result of the PD (25.3%) and Umberto Ambrosoli's personal list (7.0%).

- Combined result of the PD (19.2%) and Giorgio Gori's personal list (3.0%).

- Combined result of the PD (16.7%) and Alessandra Moretti's personal list (3.8%).

- Combined result of the PD (29.7%) and Nicola Zingaretti's personal list (4.5%).

- Combined result of the PD (21.2%) and Nicola Zingaretti's personal list (4.3%).

- Combined result of the PD (19.5%), Vincenzo De Luca's personal list (4.9%) and Free Campania (4.8%).

- Combined result of the PD (18.8%) and Michele Emiliano's personal lists (9.2%+4.1%).

- Combined result of the PD (15.8%) and Agazio Loiero's personal list (7.0%).

- Combined result of the PD (23.7%) and Mario Oliverio's personal list (12.5%).

- Combined result of the PD (13.0%), the PD-sponsored Pact of Democrats for Reforms and Fabrizio Micari's personal list (2.2%).

Electoral results

Italian Parliament

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 12,434,260 (2nd) | 33.1 | 217 / 630 |

||

| 2013 | 8,934,009 (1st) | 25.5 | 297 / 630 |

||

| 2018 | 6,161,896 (2nd) | 18.8 | 112 / 630 |

||

| Senate of the Republic | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 11,052,577 (2nd) | 33.1 | 118 / 315 |

||

| 2013 | 8,400,255 (1st) | 27.4 | 112 / 315 |

||

| 2018 | 5,783,360 (2nd) | 19.1 | 54 / 315 |

||

European Parliament

| European Parliament | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 8,008,203 (2nd) | 26.1 | 21 / 72 |

||

| 2014 | 11,203,231 (1st) | 40.8 | 31 / 73 |

||

| 2019 | 6,089,853 (2nd) | 22.7 | 19 / 76 |

||

Regional Councils

| Region | Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aosta Valley | 2018 | 3,436 (9th) | 5.4 | 0 / 35 |

|

| Piedmont | 2019 | 430,902 (2nd) | 22.4 | 10 / 51 |

|

| Lombardy | 2018 | 1,008,496 (2nd) | 19.2 | 16 / 80 |

|

| South Tyrol | 2018 | 10,806 (7th) | 3.8 | 1 / 35 |

|

| Trentino | 2018 | 35,530 (2nd) | 13.9 | 5 / 35 |

|

| Veneto | 2015 | 308,438 (3rd) | 16.7 | 9 / 51 |

|

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 2018 | 76,423 (2nd) | 18.1 | 10 / 49 |

|

| Emilia-Romagna | 2020 | 749,976 (1st) | 34.7 | 23 / 50 |

|

| Liguria | 2015 | 138,190 (1st) | 25.6 | 8 / 31 |

|

| Tuscany | 2015 | 614,869 (1st) | 46.3 | 25 / 41 |

|

| Marche | 2015 | 186,357 (1st) | 35.8 | 16 / 31 |

|

| Umbria | 2019 | 93,296 (2nd) | 22.3 | 5 / 21 |

|

| Lazio | 2018 | 539,131 (2nd) | 21.2 | 18 / 51 |

|

| Abruzzo | 2019 | 66,796 (3rd) | 11.1 | 4 / 31 |

|

| Molise | 2018 | 13,122 (3rd) | 9.0 | 2 / 21 |

|

| Campania | 2015 | 443,722 (1st) | 19.5 | 16 / 51 |

|

| Apulia | 2015 | 316,876 (1st) | 19.8 | 14 / 51 |

|

| Basilicata | 2019 | 22,423 (5th) | 7.7 | 3 / 21 |

|

| Calabria | 2020 | 118,249 (1st) | 15.2 | 6 / 31 |

|

| Sicily | 2017 | 250,633 (3rd) | 13.0 | 12 / 70 |

|

| Sardinia | 2019 | 96,235 (1st) | 13.5 | 8 / 60 |

Leadership

- Secretary: Walter Veltroni (2007–2009), Dario Franceschini (2009), Pier Luigi Bersani (2009–2013), Guglielmo Epifani (2013), Matteo Renzi (2013–2018), Maurizio Martina (2018), Nicola Zingaretti (2019–present)

- Deputy Secretary: Dario Franceschini (2007–2009), Enrico Letta (2009–2013), Lorenzo Guerini (2014–2017), Debora Serracchiani (2014–2017), Maurizio Martina (2017–2018), Andrea Orlando (2019–present), Paola De Micheli (2019)

- Coordinator of the Secretariat: Goffredo Bettini (2007–2009), Maurizio Migliavacca (2009–2013), Luca Lotti (2013–2014), Lorenzo Guerini (2014–2018), Matteo Mauri (2018), Andrea Martella (2019–present)

- Organizational Secretary: Giuseppe Fioroni (2007–2009), Maurizio Migliavacca (2009), Nico Stumpo (2009–2013), Davide Zoggia (2013–2013), Luca Lotti (2013–2014), Lorenzo Guerini (2014–2017), Andrea Rossi (2017–2018), Gianni Dal Moro (2018–2019), Stefano Vaccari (2019–present)

- Spokesperson: Andrea Orlando (2008–2013), Lorenzo Guerini (2013–2014), Alessia Rotta (2014–2017), Matteo Richetti (2017–2018), Marianna Madia (2018)

- Treasurer: Mauro Agostini (2007–2009), Antonio Misiani (2009–2013), Francesco Bonifazi (2013–2019), Luigi Zanda (2019–2020)

- President: Romano Prodi (2007–2008), Anna Finocchiaro (acting,[242] 2008–2009), Rosy Bindi (2009–2013), Gianni Cuperlo (2013–2014), Matteo Orfini (2014–2019), Paolo Gentiloni (2019), Valentina Cuppi (2020–present)

- Vice President: Marina Sereni (2009–2013), Ivan Scalfarotto (2009–2013), Matteo Ricci (2013–2017), Sandra Zampa (2013–2017), Domenico De Santis (2017–2019), Barbara Pollastrini (2017–2019), Anna Ascani (2019–present), Debora Serracchiani (2019–present)

- Party Leader in the Chamber of Deputies: Antonello Soro (2007–2009), Dario Franceschini (2009–2013), Roberto Speranza (2013–2015), Ettore Rosato (2015–2018), Graziano Delrio (2018–present)

- Party Leader in the Senate: Anna Finocchiaro (2007–2013), Luigi Zanda (2013–2018), Andrea Marcucci (2018–present)

- Party Leader in the European Parliament: David Sassoli (2009–2014), Patrizia Toia (2014–2019), Roberto Gualtieri (2019), Brando Benifei (2009–present)

References

- "Convenzione nazionale 2019". 3 February 2019.

- Richard Collin; Pamela L. Martin (2012). An Introduction to World Politics: Conflict and Consensus on a Small Planet. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4422-1803-1. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Gianfranco Pasquino (2016). "Italy". In Jean-Michel de Waele; Fabien Escalona; Mathieu Vieira (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Social Democracy in the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-137-29380-0.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Italy". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- Fotia, Mauro (2011). Il consociativismo infinito: dal centro-sinistra al Partito democratico. Edizioni Dedalo. Bari. p. 232. ISBN 9788822063182.

- "Salvati: "La maggioranza liberale di sinistra ha rigenerato il partito democratico"". LaStampa.it. May 2017.

- "Simbolo di unità. Nicola Zingaretti svela il logo Pd-SiamoEuropei". Huffington Post (in Italian). 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Britannica Educational Publishing (2013). Italy. Britanncia Educational Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-61530-989-4.

- "Il Pd come la Dc? Le coincidenze e le differenze" (in Italian). Europa. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

il Pd [...] continua a sostenere la tesi che la sua area di riferimento è la sinistra e il centro sinistra e non un “centro che guarda a sinistra” di degasperiana memoria.

- "Primarie Pd, vince Zingaretti. Il comitato del neosegretario: "Siamo oltre il 67%. affluenza a 1milione e 800mila, meglio del 2017"". La Repubblica. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Pd, l'Assemblea nazionale elegge Valentina Cuppi presidente". la Repubblica (in Italian). 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Hans Slomp (2011). Europe, a Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-313-39181-1. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Vespa, Bruno (2010). Il Cuore e la Spada: Storia politica e romantica dell'Italia unita, 1861-2011. Mondadori. p. 650. ISBN 9788852017285.

- Augusto, Giuliano (8 December 2013), "De profundis per il Pd", Rinascita, archived from the original on 1 March 2014

- Gioli, Sergio (19 November 2013), "Ultimo treno a sinistra", Quotidiano.net

- "Appello" (PDF). Partito Democratico. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Franchetto" (PDF). Antonio di Pietro. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Pd, è nato il comitato dei 45. Prodi: "Nessuna egemonia Ds o Dl"". La Repubblica (in Italian). 22 May 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- "Pd: colombo ritira candidatura" (in Italian). La Repubblica. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- "PD: BOCCIATE CANDIDATURE DI PIETRO E PANNELLA". ANSA (in Italian). 31 July 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- "Pd: collegio garanti decidera' domani su pannella". ANSA (in Italian). 2 August 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- "L'Unione Sarda". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- "Italy's Veltroni elected new centre-left party's leader: projections". AFP. 14 October 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- "Rome Mayor Walter Veltroni pronounced leader of Italy's new Democratic Party". International Herald Tribune. 27 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "Tricolore e ramoscello di ulivo. Ecco il nuovo simbolo del Pd". La Repubblica (in Italian). 21 November 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- "List of present electoral political polls" (in Italian). President of the Council of Ministers of Italy - Department for Media and Publishing. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "ABRUZZO/ELEZIONI: IL CENTROSINISTRA PUNTA TUTTO SU COSTANTINI (IDV)". ASCA (in Italian). 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Veltroni: con Di Pietro alleanza finita". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 19 October 2008.

- "Italy's Left gets new leader". France 24. 22 February 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "Italian opposition elects leader". BBC News. 21 February 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- "EUROPEE: VICINO ACCORDO PD-VERDI-SOCIALISTI. SD E PRC IN DIFFICOLTA'". ASCA (in Italian). 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- "Regolamento per l'elezione del Segretario e dell'Assemblea Nazionale". Partito Democratico.

- "Pd, l'11 ottobre il congresso, il 25 le primarie | Sky TG24". tg24.sky.it.

- https://www.partitodemocratico.it/archivio/regolamento-per-lelezione-del-segretario-e-dellassemblea-nazionale

- https://tg24.sky.it/politica/2009/06/26/Pd_l11_ottobre_il_congresso_il_25_le_primarie.html

- http://www.repubblica.it/ultimora/24ore/PD-RESTANO-TRE-IN-CORSA-ESCLUSO-RUTIGLIANO/news-dettaglio/3699474

- "I dati definitivi dei congressi di circolo". Partito Democratico. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- "La squadra di Bersani Letta sarà numero due Scalfarotto vicepresidente". Corriere della Sera. 24 December 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- "Bersani segretario: siamo l' alternativa Sulle riforme confronto in Parlamento". Corriere Della Sera. 24 December 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- "Alleanza per l'Italia prima convention a Parma". Parma la Repubblica. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- "Deputati e Organi Parlamentari - Composizione gruppi Parlamentari". Camera. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Variazioni nella composizione dei gruppi del Senato nella XVI Legislatura". Archived from the original on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- "Nord, gli ex Popolari escono dal Pd Malumore cattolico anche in Calabria". Corriere della Sera. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "E Di Pietro attacca il "caro Pier Luigi" "Eviti me e Vendola per rincorrere Casini"". Corriere Della Sera. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Bersani: nuovo Ulivo con Di Pietro e Vendola". Corriere della Sera. 17 September 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "La "foto di Vasto" agita il Pd". Corriere Della Sera. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Sponda moderata o unione a sinistra Quali alleanze per il Partito democratico". Corriere Della Sera. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Via libera definitivo a Monti "Clima nuovo, ce la faremo"". Corriere della Sera. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Camera, fiducia ampia Il Pdl: esecutivo di tregua, l' Ici si può riesaminare". Corriere Della Sera. 19 November 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Via all'alleanza Pd-Vendola E su Monti nasce un caso". Corriere della Sera. 14 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Il centrosinistra "ignora" il premier". Corriere della Sera. 13 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Renzi: si fa una nuova Italia E cerca i voti dei delusi pdl". Corriere della Sera. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Tortelli e officina, Bersani: ecco chi sono". Corriere della Sera. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Commozione e ricordi Bettola, dove il segretario è ancora "il Gigi"". Corriere della Sera. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Il Pd sceglie i miti del passato per costruire una nuova identità". Corriere della Sera. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Vendola fa litigare Bersani e Casini". Corriere della Sera. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ""Riscrivi l'Italia": parte la campagna per le primarie". Partito Democratico. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "La Sicilia a Crocetta Balzo dei Cinque Stelle". Corriere Della Sera. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Sicilia - Elezioni Regionali 28 ottobre 2012". La Repubblica. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Italy's Bersani proposes ex-Senate speaker as president". IB Times. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Parlamento in seduta comune". Camera. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Prodi to be centre left's new Italian president candidate". ANSA. 16 April 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Prodi fails in bid to unite PD". ANSA. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Paola Pica. "Pd in pezzi, Bersani furioso si dimette: «Non posso accettare il grave gesto contro Prodi". Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Pd, Epifani eletto segretario. Letta: è una buona notizia per governo". Reuters. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Ministero Dell'Interno - Notizie Archived 29 June 2013 at Archive.today. Interno.gov.it (15 April 2013). Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- Redazione Il Fatto Quotidiano (1 January 1970). "Pd, Epifani: "Organizziamo congresso Pse". Fioroni: "Allora torna la Margherita" - Il Fatto Quotidiano". Ilfattoquotidiano.it. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Epifani non si candiderà al Congresso. "Le accuse di Grillo a Rodotà sono volgari e inammissibili" - International Business Times". It.ibtimes.com. 31 May 2013. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Redazione Il Fatto Quotidiano (15 July 2013). "Pd, Epifani si tira fuori: "Non mi candiderò a guida del partito, sarebbe tradimento" - Il Fatto Quotidiano". Ilfattoquotidiano.it. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Internazionale » Partito democratico » Epifani: sondaggi favorevoli per me, ma non mi candiderò". Internazionale.it. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Economia e Finanza - Corriere della Sera". Ilmondo.it. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Primarie Pd, candidati depositano le firme. Si allunga lista dei lettiani pro Renzi". Repubblica.it. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Risultati definitivi del voto degli iscritti | Partito Democratico". Partitodemocratico.it. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "It works!". Primariepd2013.it. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Heading off the populists". The Economist. 14 December 2013.

- MonrifNet (15 December 2013). "Pd, Renzi segretario: "Con Letta patto di 15 mesi. Grillo, o ci stai o sei un buffone" / SCHEDA - Quotidiano Net". Qn.quotidiano.net. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Andrea Carugati. "Intervista a Cuperlo: "No alle liste bloccate" - Politica - l'Unità - notizie online lavoro, recensioni, cinema, musica". Unita.it. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Pd, Cuperlo si dimette da presidente. Renzi replica: "Le critiche si accettano"". Repubblica.it. 21 January 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Davies, Lizzy (13 February 2014), "Italian PM Enrico Letta to resign", The Guardian

- "Renzi liquida Letta: "Via dalla palude" Venerdì il premier al Quirinale per le dimissioni", Corriere.it, 13 February 2014

- Rubino, Monica (22 February 2014), "Il governo Renzi ha giurato al Colle, è in carica. Gelo con Letta alla consegna della campanella", Repubblica.it

- "Italian Partito Democratico Officially Welcomed into the PES Family". Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "UPDATE 2-Renzi's triumph in EU vote gives mandate for Italian reform". Reuters. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Italy's Mogherini and Poland's Tusk get top EU jobs". BBC News. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Camera.it - XVII Legislatura - Deputati e Organi- Composizione gruppi Parlamentari". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "senato.it - Senato della Repubblica senato.it - Variazioni nei Gruppi parlamentari". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Cofferati lascia il Partito Democratico "Inaccettabile il silenzio del partito" - Corriere.it". Corriere della Sera. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Civati lascia. Il Pd: non ci preoccupa Ora anche Fassina pensa all?addio". corriere.it. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Fassina dice addio al Pd: "Non ci sono le condizioni per continuare"". Repubblica.it. 23 June 2015.

- "Il novembre caldo degli anti Renzi". L'Huffington Post. 31 October 2015.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times.

- "Italy's Renzi Quits as Party Leader, Triggers Re-Election Fight". 19 February 2017 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- "Renzi si dimette e sfida la minoranza. "Così il segretario sceglie la via della scissione"". Il Sole 24 Ore.

- "Pd: fra congresso e scissione cosa succede adesso. Renzi punta alle primarie il 9 aprile". La Stampa. 20 February 2017.

- "Assemblea Pd, Renzi non media con la minoranza: "No ai ricatti". " Emiliano, Rossi e Speranza: "Ha scelto la scissione" - Il Fatto Quotidiano". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 19 February 2017.

- "Pd, arrivata candidatura di Renzi: è corsa a tre con Emiliano e Andrea Orlando". Repubblica.it. 6 March 2017.

- Stefanoni, Franco (25 February 2017). "Ecco il nome degli ex Pd: Articolo 1 Movimento dei democratici e progressisti".

- ""Democratici e progressisti" il nuovo nome degli ex Pd. Speranza: lavoro è nostra priorità". Il Sole 24 ORE.

- Binelli, Raffaello. "Nasce il Movimento democratici e progressisti". ilGiornale.it.

- "Camera.it - XVII Legislatura - Deputati e Organi- Composizione gruppi Parlamentari". www.camera.it.

- "senato.it - Senato della Repubblica senato.it - Variazioni nei Gruppi parlamentari". www.senato.it.

- "Liberi e uguali, Grasso: 'Ecco la nuova sinistra' - Politica". ANSA.it. 3 December 2017.

- "Sinistra, Grasso lancia 'Liberi e uguali': "Pd mi ha offerto incarichi ma i calcoli non fanno per me"". Repubblica.it. 3 December 2017.

- "Pietro Grasso lascia il gruppo del Pd: 'Fiducia una violenza' - Politica". ANSA.it. 26 October 2017.

- "Senato, il presidente Pietro Grasso lascia gruppo Pd. Zanda: "Dissenso su linea del partito"". Repubblica.it. 26 October 2017.

- "Grasso, il ragazzo di sinistra, lascia il Pd. "La misura è colma". Pesano le fiducie sul Rosatellum. Mdp lo aspetta come leader". L’Huffington Post. 26 October 2017.

- "Primarie: Renzi 70,01%; Orlando 19,50%; Emiliano 10,49%; votanti 1.848.658 - Partito Democratico". 1 May 2017.

- "I risultati delle primarie del PD, spezzettati - Il Post". 1 May 2017.

- Meli, Maria Teresa (3 July 2018). "Renzi, ecco la lettera di dimissioni: "Sono già fuori"". Corriere della Sera.

- "Direzione Pd approva all'unanimità la relazione di Martina: "No a governi con centrodestra e M5S. Basta odi feroci tra noi"". Repubblica.it. 3 May 2018.

- "Pd, Franceschini: "Abbiamo il dovere di tenere aperto il dialogo con il M5s. Li abbiamo spinti nelle braccia di Salvini"". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 9 July 2018.

- Curridori, Francesco. "Carlo Calenda lancia la sfida: "Mi iscrivo al Pd"". ilGiornale.it.

- "Carlo Calenda (Pd): 'Bisogna andare oltre il Pd serve un movimento più ampio'" – via www.la7.it.

- "Pd, Calenda lancia il manifesto del Fronte Repubblicano: "Cinque idee per ricostruire"". Repubblica.it. 27 June 2018.

- "Pd, il pallino resta in mano a Renzi - ItaliaOggi.it".

- "Assemblea Pd, Renzi non molla il partito: "Non vado via. Ci rivedremo al congresso e perderete di nuovo"". Il Fatto Quotidiano. 7 July 2018.

- "Pd, Martina nuovo segretario. Renzi contestato. Zingaretti: "Non ascolta, è un limite enorme"". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 6 July 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Quotidiano.Net (18 November 2018). "Pd, Martina si dimette da segretario: "Ora Unità". Renzi non c'è". Quotidiano.Net (in Italian). Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Vecchio, Concetto (30 September 2018). "Pd, 70mila alla manifestazione a Roma. I militanti: "Vogliamo unità". Martina: "A noi piacciono le piazze non i balconi"". Repubblica.it (in Italian). Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Calenda lancia Manifesto "Siamo Europei", Zingaretti e Martina: "Candidati primarie aprano insieme la campagna per maggio"". L’Huffington Post (in Italian). 18 January 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "L'Italia e l'Europa sono più forti di chi le vuole deboli!". Siamo Europei (in Italian). Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Cosa sta facendo Carlo Calenda?". Il Post (in Italian). 4 February 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.