Economy of India

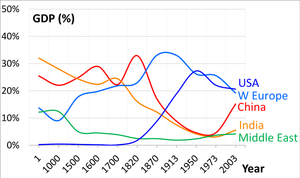

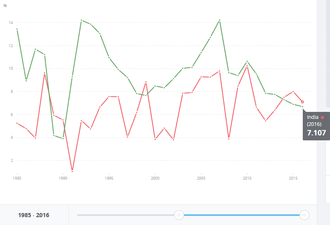

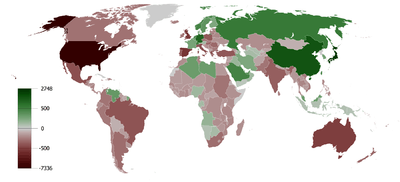

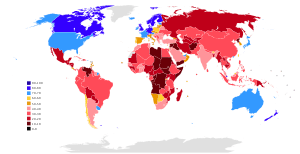

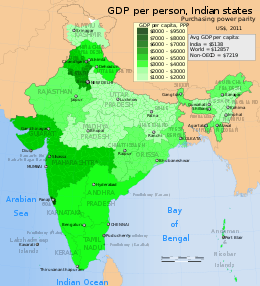

The economy of India is characterised as a developing market economy.[44][45] It is the world's fifth-largest economy by nominal GDP and the third-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP). According to the IMF, on a per capita income basis, India ranked 139th by GDP (nominal) and 118th by GDP (PPP) in 2018.[46] From independence in 1947 until 1991, successive governments promoted protectionist economic policies with extensive state intervention and regulation; the end of the Cold War and an acute balance of payments crisis in 1991 led to the adoption of a broad program of economic liberalisation.[47][48] Since the start of the 21st century, annual average GDP growth has been 6% to 7%,[45] and from 2014 to 2018, India was the world's fastest growing major economy, surpassing China.[49][50] Historically, India was the largest economy in the world for most of the two millennia from the 1st until 19th century.[51][52][53]

| |

| Currency | Indian rupee (INR, ₹) |

|---|---|

| 1 April – 31 March | |

Trade organisations | WTO, WCO, SAFTA, BIMSTEC, WFTU, BRICS, G-20, BIS, AIIB, ADB and others |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

GDP by component |

|

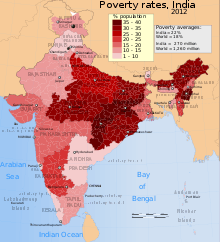

Population below poverty line |

|

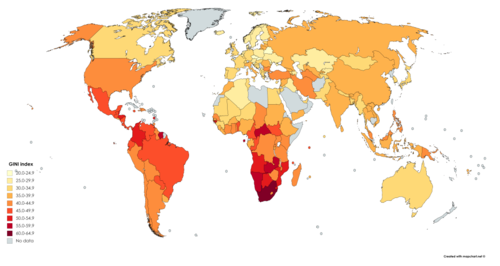

| 33.9 medium (2013)[16] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries |

|

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods |

|

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods |

|

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock |

|

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| |

| −3.4% (of GDP) (2018–19)[36] | |

| Revenues |

|

| Expenses |

|

| Economic aid | |

Foreign reserves | |

The long-term growth perspective of the Indian economy remains positive due to its young population and corresponding low dependency ratio, healthy savings and investment rates, and is increasing integration into the global economy.[9] The economy slowed in 2017, due to shocks of "demonetisation" in 2016 and introduction of Goods and Services Tax in 2017.[9] Nearly 60% of India's GDP is driven by domestic private consumption[54] and continues to remain the world's sixth-largest consumer market.[55] Apart from private consumption, India's GDP is also fueled by government spending, investment, and exports.[56] In 2018, India was the world's tenth-largest importer and the nineteenth-largest exporter.[57] India has been a member of World Trade Organization since 1 January 1995.[58] It ranks 63rd on Ease of doing business index and 68th on Global Competitiveness Report.[59] With 520-million-workers, the Indian labour force is the world's second-largest as of 2019. India has one of the world's highest number of billionaires and extreme income inequality.[60][61] Since India has a vast informal economy, barely 2% of Indians pay income taxes.[62] During the 2008 global financial crisis the economy faced mild slowdown, India undertook stimulus measures (both fiscal and monetary) to boost growth and generate demand; in subsequent years economic growth revived.[63] According to 2017 PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report, India's GDP at purchasing power parity could overtake that of the United States by 2050.[64] According to World Bank, to achieve sustainable economic development India must focus on public sector reform, infrastructure, agricultural and rural development, removal of land and labour regulations, financial inclusion, spur private investment and exports, education and public health.[65]

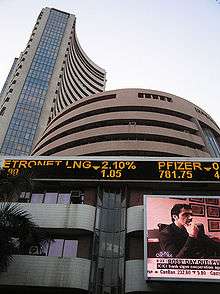

In 2019, India's ten largest trading partners were USA, China, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, Iraq, Singapore, Germany, South Korea and Switzerland.[66] In 2018–19, the foreign direct investment (FDI) in India was $64.4 billion with service sector, computer, and telecom industry remains leading sectors for FDI inflows.[67] India has free trade agreements with several nations, including ASEAN, SAFTA, Mercosur, South Korea, Japan and few others which are in effect or under negotiating stage.[68][69] The service sector makes up 55.6% of GDP and remains the fastest growing sector, while the industrial sector and the agricultural sector employs majority of the labor force.[70] The Bombay Stock Exchange and National Stock Exchange are one of the world's largest stock exchanges by market capitalization.[71] India is the world's sixth-largest manufacturer, representing 3% of global manufacturing output and employs over 57 million people.[72][73] Nearly 66% of India's population is rural whose primary source of livelihood is agriculture,[74] and contributes about 50% of India's GDP.[75] It has the world's fifth-largest foreign-exchange reserves worth ₹38,832.21 billion (US$540 billion).[76][43] India has a high national debt with 68% of GDP, while its fiscal deficit remained at 3.4% of GDP.[35][36] However, as per 2019 CAG report, the actual fiscal deficit is 5.85% of GDP.[77] India's government-owned banks faced mounting bad debt, resulting in low credit growth,[9] simultaneously the NBFC sector has been engulfed in a liquidity crisis.[78] India faces high unemployment, rising income inequality, and major slump in aggregate demand.[79][80] In recent years, independent economists and financial institutions have accused the government of fudging various economic data, especially GDP growth.[81][82]

India ranks second globally in food and agricultural production, while agricultural exports were $38.5 billion.[75][83] The construction and real estate sector is the second largest employer after agriculture, and a vital sector to gauge economic activity.[84] The Indian textiles industry is estimated at $150 billion and contributes 7% of industrial output and 2% of India's GDP while employs over 45 million people directly.[85] The Indian IT industry is a major exporter of IT services with $180 billion in revenue and employs over four million people.[86] India's telecommunication industry is the world's second largest by number of mobile phone, smartphone, and internet users. It is the world's tenth-largest oil producer and the third-largest oil consumer.[87] The Indian automobile industry is the world's fourth largest by production.[88][89] It has $672 billion worth of retail market which contributes over 10% of India's GDP and has one of world's fastest growing e-commerce markets.[90] India has the world's fourth-largest natural resources, with mining sector contributes 11% of the country's industrial GDP and 2.5% of total GDP.[91] It is also the world's second-largest coal producer, the second-largest cement producer, the second-largest steel producer, and the third-largest electricity producer.[92][93]

History

For a continuous duration of nearly 1700 years from the year 1 AD, India was the top most economy constituting 35 to 40% of world GDP.[96] The combination of protectionist, import-substitution, Fabian socialism, and social democratic-inspired policies governed India for sometime after the end of British rule. The economy was then characterised by extensive regulation, protectionism, public ownership of large monopolies, pervasive corruption and slow growth.[47][48][97] Since 1991, continuing economic liberalisation has moved the country towards a market-based economy.[47][48] By 2008, India had established itself as one of the world's faster-growing economies.

Ancient and medieval eras

Indus Valley Civilisation

The citizens of the Indus Valley Civilisation, a permanent settlement that flourished between 2800 BC and 1800 BC, practised agriculture, domesticated animals, used uniform weights and measures, made tools and weapons, and traded with other cities. Evidence of well-planned streets, a drainage system and water supply reveals their knowledge of urban planning, which included the first-known urban sanitation systems and the existence of a form of municipal government.[98]

West Coast

Maritime trade was carried out extensively between South India and Southeast and West Asia from early times until around the fourteenth century AD. Both the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts were the sites of important trading centres from as early as the first century BC, used for import and export as well as transit points between the Mediterranean region and southeast Asia.[99] Over time, traders organised themselves into associations which received state patronage. Historians Tapan Raychaudhuri and Irfan Habib claim this state patronage for overseas trade came to an end by the thirteenth century AD, when it was largely taken over by the local Parsi, Jewish, Syrian Christian and Muslim communities, initially on the Malabar and subsequently on the Coromandel coast.[100]

Silk Route

Other scholars suggest trading from India to West Asia and Eastern Europe was active between the 14th and 18th centuries.[101][102][103] During this period, Indian traders settled in Surakhani, a suburb of greater Baku, Azerbaijan. These traders built a Hindu temple, which suggests commerce was active and prosperous for Indians by the 17th century.[104][105][106][107]

Further north, the Saurashtra and Bengal coasts played an important role in maritime trade, and the Gangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce. Most overland trade was carried out via the Khyber Pass connecting the Punjab region with Afghanistan and onward to the Middle East and Central Asia.[108] Although many kingdoms and rulers issued coins, barter was prevalent. Villages paid a portion of their agricultural produce as revenue to the rulers, while their craftsmen received a part of the crops at harvest time for their services.[109]

Mughal era (1526–1793)

The Indian economy was large and prosperous under the Mughal Empire, up until the 18th century.[110] Sean Harkin estimates China and India may have accounted for 60 to 70 percent of world GDP in the 17th century. The Mughal economy functioned on an elaborate system of coined currency, land revenue and trade. Gold, silver and copper coins were issued by the royal mints which functioned on the basis of free coinage.[111] The political stability and uniform revenue policy resulting from a centralised administration under the Mughals, coupled with a well-developed internal trade network, ensured that India–before the arrival of the British–was to a large extent economically unified, despite having a traditional agrarian economy characterised by a predominance of subsistence agriculture,[112] with 64% of the workforce in the primary sector (including agriculture), but with 36% of the workforce also in the secondary and tertiary sectors,[113] higher than in Europe, where 65–90% of its workforce were in agriculture in 1700 and 65–75% were in agriculture in 1750.[114] Agricultural production increased under Mughal agrarian reforms,[110] with Indian agriculture being advanced compared to Europe at the time, such as the widespread use of the seed drill among Indian peasants before its adoption in European agriculture,[115] and higher per-capita agricultural output and standards of consumption.[116]

The Mughal Empire had a thriving industrial manufacturing economy, with India producing about 25% of the world's industrial output up until 1750,[117] making it the most important manufacturing center in international trade.[118] Manufactured goods and cash crops from the Mughal Empire were sold throughout the world. Key industries included textiles, shipbuilding, and steel, and processed exports included cotton textiles, yarns, thread, silk, jute products, metalware, and foods such as sugar, oils and butter.[110] Cities and towns boomed under the Mughal Empire, which had a relatively high degree of urbanization for its time, with 15% of its population living in urban centres, higher than the percentage of the urban population in contemporary Europe at the time and higher than that of British India in the 19th century.[119]

In early modern Europe, there was significant demand for products from Mughal India, particularly cotton textiles, as well as goods such as spices, peppers, indigo, silks, and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[110] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughal Indian textiles and silks. From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, Mughal India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia, and the Bengal Subah province alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[120] In contrast, there was very little demand for European goods in Mughal India, which was largely self-sufficient.[110] Indian goods, especially those from Bengal, were also exported in large quantities to other Asian markets, such as Indonesia and Japan.[121] At the time, Mughal Bengal was the most important center of cotton textile production.[122]

In the early 18th century, the Mughal Empire declined, as it lost western, central and parts of south and north India to the Maratha Empire, which integrated and continued to administer those regions.[123] The decline of the Mughal Empire led to decreased agricultural productivity, which in turn negatively affected the textile industry.[124] The subcontinent's dominant economic power in the post-Mughal era was the Bengal Subah in the east., which continued to maintain thriving textile industries and relatively high real wages.[125] However, the former was devastated by the Maratha invasions of Bengal[126][127] and then British colonization in the mid-18th century.[125] After the loss at the Third Battle of Panipat, the Maratha Empire disintegrated into several confederate states, and the resulting political instability and armed conflict severely affected economic life in several parts of the country – although this was mitigated by localised prosperity in the new provincial kingdoms.[123] By the late eighteenth century, the British East India Company had entered the Indian political theatre and established its dominance over other European powers. This marked a determinative shift in India's trade, and a less-powerful impact on the rest of the economy.[128]

British era (1793–1947)

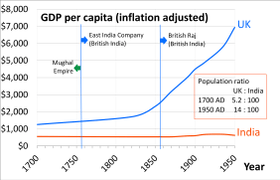

There is no doubt that our grievances against the British Empire had a sound basis. As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India's share of world income collapsed from 22.6% in 1700, almost equal to Europe's share of 23.3% at that time, to as low as 3.8% in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the British East India Company's gradual expansion and consolidation of power brought a major change in taxation and agricultural policies, which tended to promote commercialisation of agriculture with a focus on trade, resulting in decreased production of food crops, mass impoverishment and destitution of farmers, and in the short term, led to numerous famines.[130] The economic policies of the British Raj caused a severe decline in the handicrafts and handloom sectors, due to reduced demand and dipping employment.[131] After the removal of international restrictions by the Charter of 1813, Indian trade expanded substantially with steady growth.[132] The result was a significant transfer of capital from India to England, which, due to the colonial policies of the British, led to a massive drain of revenue rather than any systematic effort at modernisation of the domestic economy.[133]

Under British rule, India's share of the world economy declined from 24.4% in 1700 down to 4.2% in 1950. India's GDP (PPP) per capita was stagnant during the Mughal Empire and began to decline prior to the onset of British rule.[52] India's share of global industrial output declined from 25% in 1750 down to 2% in 1900.[117] At the same time, the United Kingdom's share of the world economy rose from 2.9% in 1700 up to 9% in 1870. The British East India Company, following their conquest of Bengal in 1757, had forced open the large Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, compared to local Indian producers who were heavily taxed, while in Britain protectionist policies such as bans and high tariffs were implemented to restrict Indian textiles from being sold there, whereas raw cotton was imported from India without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles from Indian cotton and sold them back to the Indian market. British economic policies gave them a monopoly over India's large market and cotton resources.[140][141][142] India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[143]

British territorial expansion in India throughout the 19th century created an institutional environment that, on paper, guaranteed property rights among the colonisers, encouraged free trade, and created a single currency with fixed exchange rates, standardised weights and measures and capital markets within the company-held territories. It also established a system of railways and telegraphs, a civil service that aimed to be free from political interference, a common-law and an adversarial legal system.[144] This coincided with major changes in the world economy – industrialisation, and significant growth in production and trade. However, at the end of colonial rule, India inherited an economy that was one of the poorest in the developing world,[145] with industrial development stalled, agriculture unable to feed a rapidly growing population, a largely illiterate and unskilled labour force, and extremely inadequate infrastructure.[146]

The 1872 census revealed that 91.3% of the population of the region constituting present-day India resided in villages.[147] This was a decline from the earlier Mughal era, when 85% of the population resided in villages and 15% in urban centers under Akbar's reign in 1600.[148] Urbanisation generally remained sluggish in British India until the 1920s, due to the lack of industrialisation and absence of adequate transportation. Subsequently, the policy of discriminating protection (where certain important industries were given financial protection by the state), coupled with the Second World War, saw the development and dispersal of industries, encouraging rural–urban migration, and in particular the large port cities of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras grew rapidly. Despite this, only one-sixth of India's population lived in cities by 1951.[149]

The impact of British rule on India's economy is a controversial topic. Leaders of the Indian independence movement and economic historians have blamed colonial rule for the dismal state of India's economy in its aftermath and argued that financial strength required for industrial development in Britain was derived from the wealth taken from India. At the same time, right-wing historians have countered that India's low economic performance was due to various sectors being in a state of growth and decline due to changes brought in by colonialism and a world that was moving towards industrialisation and economic integration.[150]

Several economic historians have argued that real wage decline occurred in the early 19th century, or possibly beginning in the very late 18th century, largely as a result of British imperialism. Economic historian Prasannan Parthasarathi presented earnings data which showed real wages and living standards in 18th century Bengal and Mysore being higher than in Britain, which in turn had the highest living standards in Europe.[138][117] Mysore's average per-capita income was five times higher than subsistence level,[151] i.e. five times higher than $400 (1990 international dollars),[152] or $2,000 per capita. In comparison, the highest national per-capita incomes in 1820 were $1,838 for the Netherlands and $1,706 for Britain.[153] It has also been argued that India went through a period of deindustrialization in the latter half of the 18th century as an indirect outcome of the collapse of the Mughal Empire.[117]

Pre-liberalisation period (1947–1991)

Indian economic policy after independence was influenced by the colonial experience, which was seen as exploitative by Indian leaders exposed to British social democracy and the planned economy of the Soviet Union.[146] Domestic policy tended towards protectionism, with a strong emphasis on import substitution industrialisation, economic interventionism, a large government-run public sector, business regulation, and central planning,[154] while trade and foreign investment policies were relatively liberal.[155] Five-Year Plans of India resembled central planning in the Soviet Union. Steel, mining, machine tools, telecommunications, insurance, and power plants, among other industries, were effectively nationalised in the mid-1950s.[156]

Never talk to me about profit, Jeh, it is a dirty word.

— Nehru, India's Fabian Socialism-inspired first prime minister to industrialist J.R.D. Tata, when Tata suggested state-owned companies should be profitable[159]

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, along with the statistician Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, formulated and oversaw economic policy during the initial years of the country's independence. They expected favourable outcomes from their strategy, involving the rapid development of heavy industry by both public and private sectors, and based on direct and indirect state intervention, rather than the more extreme Soviet-style central command system.[160][161] The policy of concentrating simultaneously on capital- and technology-intensive heavy industry and subsidising manual, low-skill cottage industries was criticised by economist Milton Friedman, who thought it would waste capital and labour, and retard the development of small manufacturers.[162]

I cannot decide how much to borrow, what shares to issue, at what price, what wages and bonus to pay, and what dividend to give. I even need the government's permission for the salary I pay to a senior executive.

Since 1965, the use of high-yielding varieties of seeds, increased fertilisers and improved irrigation facilities collectively contributed to the Green Revolution in India, which improved the condition of agriculture by increasing crop productivity, improving crop patterns and strengthening forward and backward linkages between agriculture and industry.[163] However, it has also been criticised as an unsustainable effort, resulting in the growth of capitalistic farming, ignoring institutional reforms and widening income disparities.[164]

In 1984, Rajiv Gandhi promised economic liberalization, he made V. P. Singh the finance minister, who tried to reduce tax-evasion and tax-receipts rose due to this crackdown although taxes were lowered. This process lost its momentum during later tenure of Mr. Gandhi as his government was marred by scandals.

Post-liberalisation period (since 1991)

The collapse of the Soviet Union, which was India's major trading partner, and the Gulf War, which caused a spike in oil prices, resulted in a major balance-of-payments crisis for India, which found itself facing the prospect of defaulting on its loans.[168] India asked for a $1.8 billion bailout loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in return demanded de-regulation.[169]

In response, the Narasimha Rao government, including Finance Minister Manmohan Singh, initiated economic reforms in 1991. The reforms did away with the Licence Raj, reduced tariffs and interest rates and ended many public monopolies, allowing automatic approval of foreign direct investment in many sectors.[170] Since then, the overall thrust of liberalisation has remained the same, although no government has tried to take on powerful lobbies such as trade unions and farmers, on contentious issues such as reforming labour laws and reducing agricultural subsidies.[171] By the turn of the 21st century, India had progressed towards a free-market economy, with a substantial reduction in state control of the economy and increased financial liberalisation.[172] This has been accompanied by increases in life expectancy, literacy rates, and food security, although urban residents have benefited more than rural residents.[173]

While the credit rating of India was hit by its nuclear weapons tests in 1998, it has since been raised to investment level in 2003 by Standard & Poor's (S&P) and Moody's.[174] India experienced high growth rates, averaging 9% from 2003 to 2007.[175] Growth then moderated in 2008 due to the global financial crisis. In 2003, Goldman Sachs predicted that India's GDP in current prices would overtake France and Italy by 2020, Germany, UK and Russia by 2025 and Japan by 2035, making it the third-largest economy of the world, behind the US and China. India is often seen by most economists as a rising economic superpower which will play a major role in the 21st-century global economy.[176][177]

Starting in 2012, India entered a period of reduced growth, which slowed to 5.6%. Other economic problems also became apparent: a plunging Indian rupee, a persistent high current account deficit and slow industrial growth.

India started recovery in 2013–14 when the GDP growth rate accelerated to 6.4% from the previous year's 5.5%. The acceleration continued through 2014–15 and 2015–16 with growth rates of 7.5% and 8.0% respectively. For the first time since 1990, India grew faster than China which registered 6.9% growth in 2015. However the growth rate subsequently decelerated, to 7.1% and 6.6% in 2016–17 and 2017–18 respectively,[178] partly because of the disruptive effects of 2016 Indian banknote demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax (India).[179]

India is ranked 63rd out of 190 countries in the World Bank's 2020 ease of doing business index, up 14 points from the last year's 100 and up 37 points in just two years.[180] In terms of dealing with construction permits and enforcing contracts, it is ranked among the 10 worst in the world, while it has a relatively favourable ranking when it comes to protecting minority investors or getting credit.[26] The strong efforts taken by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) to boost ease of doing business rankings at the state level is said to impact the overall rankings of India.[181]

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic (2020)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous rating agencies downgraded India's GDP predictions for FY21 to negative figures,[182][183] signalling a recession in India, the most severe since 1979.[184][185] According to a Dun & Bradstreet report, the country is likely to suffer a recession in the third quarter of FY2020 as a result of the over 2-month long nation-wide lockdown imposed to curb the spread of COVID-19.[186]

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2018. Inflation under 5% is in green.[187][188]

| Year | GDP (in bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

Share of world (GDP PPP in %) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 382.0 | 557 | 2.89% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||

| 1991 | 75.3% | |||||

| 1992 | ||||||

| 1993 | ||||||

| 1994 | ||||||

| 1995 | ||||||

| 1996 | ||||||

| 1997 | ||||||

| 1998 | ||||||

| 1999 | ||||||

| 2000 | ||||||

| 2001 | ||||||

| 2002 | ||||||

| 2003 | ||||||

| 2004 | ||||||

| 2005 | ||||||

| 2006 | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| 2008 | ||||||

| 2009 | ||||||

| 2010 | ||||||

| 2011 | ||||||

| 2012 | ||||||

| 2013 | ||||||

| 2014 | ||||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2016 | ||||||

| 2017 | ||||||

| 2018 |

Sectors

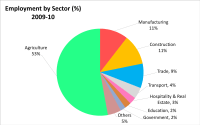

Percent labour employment in India by economic sectors (2010).[189]

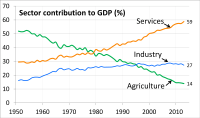

Percent labour employment in India by economic sectors (2010).[189] Contribution to GDP of India by economic sectors of the Indian economy have evolved between 1951 and 2013, as its economy has diversified and developed.

Contribution to GDP of India by economic sectors of the Indian economy have evolved between 1951 and 2013, as its economy has diversified and developed.

Historically, India has classified and tracked its economy and GDP in three sectors: agriculture, industry, and services. Agriculture includes crops, horticulture, milk and animal husbandry, aquaculture, fishing, sericulture, aviculture, forestry, and related activities. Industry includes various manufacturing sub-sectors. India's definition of services sector includes its construction, retail, software, IT, communications, hospitality, infrastructure operations, education, healthcare, banking and insurance, and many other economic activities.[190][191]

Agriculture

Agriculture and allied sectors like forestry, logging and fishing accounted for 17% of the GDP, the sector employed 49% of its total workforce in 2014.[192] Agriculture accounted for 23% of GDP, and employed 59% of the country's total workforce in 2016.[193] As the Indian economy has diversified and grown, agriculture's contribution to GDP has steadily declined from 1951 to 2011, yet it is still the country's largest employment source and a significant piece of its overall socio-economic development.[194] Crop-yield-per-unit-area of all crops has grown since 1950, due to the special emphasis placed on agriculture in the five-year plans and steady improvements in irrigation, technology, application of modern agricultural practices and provision of agricultural credit and subsidies since the Green Revolution in India. However, international comparisons reveal the average yield in India is generally 30% to 50% of the highest average yield in the world.[195] The states of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar, West Bengal, Gujarat and Maharashtra are key contributors to Indian agriculture.

India receives an average annual rainfall of 1,208 millimetres (47.6 in) and a total annual precipitation of 4000 billion cubic metres, with the total utilisable water resources, including surface and groundwater, amounting to 1123 billion cubic metres.[197] 546,820 square kilometres (211,130 sq mi) of the land area, or about 39% of the total cultivated area, is irrigated.[198] India's inland water resources and marine resources provide employment to nearly six million people in the fisheries sector. In 2010, India had the world's sixth-largest fishing industry.[199]

India is the largest producer of milk, jute and pulses, and has the world's second-largest cattle population with 170 million animals in 2011.[201] It is the second-largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, cotton and groundnuts, as well as the second-largest fruit and vegetable producer, accounting for 10.9% and 8.6% of the world fruit and vegetable production, respectively. India is also the second-largest producer and the largest consumer of silk, producing 77,000 tons in 2005.[202] India is the largest exporter of cashew kernels and cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL). Foreign exchange earned by the country through the export of cashew kernels during 2011–12 reached ₹ 43.9 billion based on statistics from the Cashew Export Promotion Council of India (CEPCI). 131,000 tonnes of kernels were exported during 2011–12.[203] There are about 600 cashew processing units in Kollam, Kerala.[200] India's foodgrain production remained stagnant at approximately 252 million tonnes (MT) during both the 2015–16 and 2014–15 crop years (July–June).[204] India exports several agriculture products, such as Basmati rice, wheat, cereals, spices, fresh fruits, dry fruits, buffalo beef meat, cotton, tea, coffee and other cash crops particularly to the Middle East, Southeast and East Asian countries. About 10 percent of its export earnings come from this trade.[205]

At around 1,530,000 square kilometres (590,000 sq mi), India has the second-largest amount of arable land, after the US, with 52% of total land under cultivation. Although the total land area of the country is only slightly more than one-third of China or the US, India's arable land is marginally smaller than that of the US, and marginally larger than that of China. However, agricultural output lags far behind its potential.[206] The low productivity in India is a result of several factors. According to the World Bank, India's large agricultural subsidies are distorting what farmers grow and hampering productivity-enhancing investment. Over-regulation of agriculture has increased costs, price risks and uncertainty, and governmental intervention in labour, land, and credit are hurting the market. Infrastructure such as rural roads, electricity, ports, food storage, retail markets and services remain inadequate.[207] The average size of land holdings is very small, with 70% of holdings being less than one hectare (2.5 acres) in size.[208] Irrigation facilities are inadequate, as revealed by the fact that only 46% of the total cultivable land was irrigated as of 2016,[198] resulting in farmers still being dependent on rainfall, specifically the monsoon season, which is often inconsistent and unevenly distributed across the country.[209] In an effort to bring an additional 20,000,000 hectares (49,000,000 acres) of land under irrigation, various schemes have been attempted, including the Accelerated Irrigation Benefit Programme (AIBP) which was provided ₹800 billion in the union budget.[210] Farming incomes are also hampered by lack of food storage and distribution infrastructure; a third of India's agricultural production is lost from spoilage.[211]

Manufacturing and Industry

Industry accounts for 26% of GDP and employs 22% of the total workforce.[212] According to the World Bank, India's industrial manufacturing GDP output in 2015 was 6th largest in the world on current US dollar basis ($559 billion),[213] and 9th largest on inflation-adjusted constant 2005 US dollar basis ($197.1 billion).[214] The industrial sector underwent significant changes due to the 1991 economic reforms, which removed import restrictions, brought in foreign competition, led to the privatisation of certain government-owned public-sector industries, liberalised the foreign direct investment (FDI) regime,[215] improved infrastructure and led to an expansion in the production of fast-moving consumer goods.[216] Post-liberalisation, the Indian private sector was faced with increasing domestic and foreign competition, including the threat of cheaper Chinese imports. It has since handled the change by squeezing costs, revamping management, and relying on cheap labour and new technology. However, this has also reduced employment generation, even among smaller manufacturers who previously relied on labour-intensive processes.[217]

Defence

.jpeg)

With strength of over 1.3 million active personnel, India has the third-largest military force and the largest volunteer army. The total budget sanctioned for the Indian military for the financial year 2019–20 was ₹3.01 lakh crore (US$42 billion).[218] Defence spending is expected to rise to US$62 billion by 2022.[219]

Electricity sector

Primary energy consumption of India is the third-largest after China and the US with 5.3% global share in the year 2015.[220] Coal and crude oil together account for 85% of the primary energy consumption of India. India's oil reserves meet 25% of the country's domestic oil demand.[221][222] As of April 2015, India's total proven crude oil reserves are 763.476 million metric tons, while gas reserves stood at 1,490 billion cubic metres (53 trillion cubic feet).[223] Oil and natural gas fields are located offshore at Bombay High, Krishna Godavari Basin and the Cauvery Delta, and onshore mainly in the states of Assam, Gujarat and Rajasthan. India is the fourth-largest consumer of oil and net oil imports were nearly ₹8,200 billion (US$110 billion) in 2014–15,[223] which had an adverse effect on the country's current account deficit. The petroleum industry in India mostly consists of public sector companies such as Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL), Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) and Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL). There are some major private Indian companies in the oil sector such as Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) which operates the world's largest oil refining complex.[224]

India became the world's third-largest producer of electricity in 2013 with a 4.8% global share in electricity generation, surpassing Japan and Russia.[225] By the end of calendar year 2015, India had an electricity surplus with many power stations idling for want of demand.[226] The utility electricity sector had an installed capacity of 303 GW as of May 2016 of which thermal power contributed 69.8%, hydroelectricity 15.2%, other sources of renewable energy 13.0%, and nuclear power 2.1%.[227] India meets most of its domestic electricity demand through its 106 billion tonnes of proven coal reserves.[228] India is also rich in certain alternative sources of energy with significant future potential such as solar, wind and biofuels (jatropha, sugarcane). India's dwindling uranium reserves stagnated the growth of nuclear energy in the country for many years.[229] Recent discoveries in the Tummalapalle belt may be among the top 20 natural uranium reserves worldwide,[230][231][232] and an estimated reserve of 846,477 metric tons (933,081 short tons) of thorium[233] – about 25% of world's reserves – are expected to fuel the country's ambitious nuclear energy program in the long-run. The Indo-US nuclear deal has also paved the way for India to import uranium from other countries.[234]

Engineering

.jpg)

Engineering is the largest sub-sector of India's industrial sector, by GDP, and the third-largest by exports.[235] It includes transport equipment, machine tools, capital goods, transformers, switchgear, furnaces, and cast and forged parts for turbines, automobiles, and railways. The industry employs about four million workers. On a value-added basis, India's engineering subsector exported $67 billion worth of engineering goods in the 2013–14 fiscal year, and served part of the domestic demand for engineering goods.[236]

The engineering industry of India includes its growing car, motorcycle and scooters industry, and productivity machinery such as tractors. India manufactured and assembled about 18 million passenger and utility vehicles in 2011, of which 2.3 million were exported.[237] India is the largest producer and the largest market for tractors, accounting for 29% of global tractor production in 2013.[237][238] India is the 12th-largest producer and 7th-largest consumer of machine tools.[237]

The automotive manufacturing industry contributed $79 billion (4% of GDP) and employed 6.76 million people (2% of the workforce) in 2016.[193]

Gems and jewellery

India is one of the largest centres for polishing diamonds and gems and manufacturing jewellery; it is also one of the two largest consumers of gold.[241][242] After crude oil and petroleum products, the export and import of gold, precious metals, precious stones, gems and jewellery accounts for the largest portion of India's global trade. The industry contributes about 7% of India's GDP, employs millions, and is a major source of its foreign-exchange earnings.[243] The gems and jewellery industry created $60 billion in economic output on value-added basis in 2017, and is projected to grow to $110 billion by 2022.[244]

The gems and jewellery industry has been economically active in India for several thousand years.[245] Until the 18th century, India was the only major reliable source of diamonds.[241] Now, South Africa and Australia are the major sources of diamonds and precious metals, but along with Antwerp, New York City, and Ramat Gan, Indian cities such as Surat and Mumbai are the hubs of world's jewellery polishing, cutting, precision finishing, supply and trade. Unlike other centres, the gems and jewellery industry in India is primarily artisan-driven; the sector is manual, highly fragmented, and almost entirely served by family-owned operations.

The particular strength of this sub-sector is in precision cutting, polishing and processing small diamonds (below one carat).[241] India is also a hub for processing of larger diamonds, pearls, and other precious stones. Statistically, 11 out of 12 diamonds set in any jewellery in the world are cut and polished in India.[246] It is also a major hub of gold and other precious-metal-based jewellery. Domestic demand for gold and jewellery products is another driver of India's GDP.[247]

Infrastructure

India's infrastructure and transport sector contributes about 5% of its GDP. India has a road network of over 5,472,144 kilometres (3,400,233 mi) as of 31 March 2015, the second-largest road network in the world only behind the United States. At 1.66 km of roads per square kilometre of land (2.68 miles per square mile), the quantitative density of India's road network is higher than that of Japan (0.91) and the United States (0.67), and far higher than that of China (0.46), Brazil (0.18) or Russia (0.08).[248] Qualitatively, India's roads are a mix of modern highways and narrow, unpaved roads, and are being improved.[249] As of 31 March 2015, 87.05% of Indian roads were paved.[248] India has the lowest kilometre-lane road density per 100,000 people among G-27 countries, leading to traffic congestion. It is upgrading its infrastructure. As of May 2014, India had completed over 22,600 kilometres (14,000 mi) of 4- or 6-lane highways, connecting most of its major manufacturing, commercial and cultural centres.[250] India's road infrastructure carries 60% of freight and 87% of passenger traffic.[251]

Indian Railways is the fourth-largest rail network in the world, with a track length of 114,500 kilometres (71,100 mi) and 7,172 stations. This government-owned-and-operated railway network carried an average of 23 million passengers a day, and over a billion tonnes of freight in 2013.[252] India has a coastline of 7,500 kilometres (4,700 mi) with 13 major ports and 60 operational non-major ports, which together handle 95% of the country's external trade by volume and 70% by value (most of the remainder handled by air).[253] Nhava Sheva, Mumbai is the largest public port, while Mundra is the largest private sea port.[254] The airport infrastructure of India includes 125 airports,[255] of which 66 airports are licensed to handle both passengers and cargo.[256]

Petroleum products and Chemicals

Petroleum products and chemicals are a major contributor to India's industrial GDP, and together they contribute over 34% of its export earnings. India hosts many oil refinery and petrochemical operations, including the world's largest refinery complex in Jamnagar that processes 1.24 million barrels of crude per day.[257] By volume, the Indian chemical industry was the third-largest producer in Asia, and contributed 5% of the country's GDP. India is one of the five-largest producers of agrochemicals, polymers and plastics, dyes and various organic and inorganic chemicals.[258] Despite being a large producer and exporter, India is a net importer of chemicals due to domestic demands.[259]

The chemical industry contributed $163 billion to the economy in FY18 and is expected to reach $300–400 billion by 2025.[260][261] The industry employed 17.33 million people (4% of the workforce) in 2016.[193]

Pharmaceuticals

The Indian pharmaceutical industry has grown in recent years to become a major manufacturer of health care products for the world. India holds a 20% market share in the global supply of generics by volume.[262] The Indian pharmaceutical sector also supplies over 62% of the global demand for various vaccines.[263] India's pharmaceutical exports stood at $17.27 billion in 2017–18 and are expected to reach $20 billion by 2020.[262] The industry grew from $6 billion in 2005 to $36.7 billion in 2016, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17.46%. It is expected to grow at a CAGR of 15.92% to reach $55 billion in 2020. India is expected to become the sixth-largest pharmaceutical market in the world by 2020.[264] It is one of the fastest-growing industrial sub-sectors and a significant contributor to India's export earnings. The state of Gujarat has become a hub for the manufacture and export of pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).[265]

Textile

The textile and apparel market in India was estimated to be $108.5 billion in 2015. It is expected to reach a size of $226 billion by 2023. The industry employees over 35 million people. By value, the textile industry accounts for 7% of India's industrial, 2% of GDP and 15% of the country's export earnings. India exported $39.2 billion worth of textiles in the 2017–18 fiscal year.[266]

India's textile industry has transformed in recent years from a declining sector to a rapidly developing one. After freeing the industry in 2004–2005 from a number of limitations, primarily financial, the government permitted massive investment inflows, both domestic and foreign. From 2004 to 2008, total investment into the textile sector increased by 27 billion dollars. Ludhiana produces 90% of woollens in India and is known as the Manchester of India. Tirupur has gained universal recognition as the leading source of hosiery, knitted garments, casual wear, and sportswear. Expanding textile centres such as Ichalkaranji enjoy one of the highest per-capita incomes in the country.[267] India's cotton farms, fibre and textile industry provides employment to 45 million people in India,[268] including some child labour (1%). The sector is estimated to employ around 400,000 children under the age of 18.[269]

Pulp and paper

The pulp and paper industry in India is one of the major producers of paper in the world and has adopted new manufacturing technology.[270] The paper market in India was estimated to be worth ₹600 billion (US$8.4 billion) in 2017–18 recording a CAGR of 6–7%. Domestic demand for paper almost doubled from around 9 million tonnes in the 2007–08 fiscal to over 17 million tonnes in 2017–18. The per capita consumption of paper in India is around 13–14 kg annually, lower than the global average of 57 kg.[271]

Services

The services sector has the largest share of India's GDP, accounting for 57% in 2012, up from 15% in 1950.[212] It is the seventh-largest services sector by nominal GDP, and third largest when purchasing power is taken into account. The services sector provides employment to 27% of the workforce. Information technology and business process outsourcing are among the fastest-growing sectors, having a cumulative growth rate of revenue 33.6% between fiscal years 1997–98 and 2002–03, and contributing to 25% of the country's total exports in 2007–08.[272]

Aviation

India is the fourth-largest civil aviation market in the world recording an air traffic of 158 million passengers in 2017.[273][274] The market is estimated to have 800 aircraft by 2020, which would account for 4.3% of global volumes,[275] and is expected to record annual passenger traffic of 520 million by 2037.[274] IATA estimated that aviation contributed $30 billion to India's GDP in 2017, and supported 7.5 million jobs – 390,000 directly, 570,000 in the value chain, and 6.2 million through tourism.[274]

Civil aviation in India traces its beginnings to 18 February 1911, when Henri Pequet, a French aviator, carried 6,500 pieces of mail on a Humber biplane from Allahabad to Naini.[276] Later on 15 October 1932, J.R.D. Tata flew a consignment of mail from Karachi to Juhu Airport. His airline later became Air India and was the first Asian airline to cross the Atlantic Ocean as well as first Asian airline to fly jets.[277]

Nationalisation

In March 1953, the Indian Parliament passed the Air Corporations Act to streamline and nationalise the then existing privately owned eight domestic airlines into Indian Airlines for domestic services and the Tata group-owned Air India for international services.[276] The International Airports Authority of India (IAAI) was constituted in 1972 while the National Airports Authority was constituted in 1986. The Bureau of Civil Aviation Security was established in 1987 following the crash of Air India Flight 182.

De-regulation

The government de-regularised the civil aviation sector in 1991 when the government allowed private airlines to operate charter and non-scheduled services under the 'Air Taxi' Scheme until 1994, when the Air Corporation Act was repealed and private airlines could now operate scheduled services. Private airlines including Jet Airways, Air Sahara, Modiluft, Damania Airways and NEPC Airlines commenced domestic operations during this period.[276]

The aviation industry experienced a rapid transformation following deregulation. Several low-cost carriers entered the Indian market in 2004–05. Major new entrants included Air Deccan, Air Sahara, Kingfisher Airlines, SpiceJet, GoAir, Paramount Airways and IndiGo. Kingfisher Airlines became the first Indian air carrier on 15 June 2005 to order Airbus A380 aircraft worth US$3 billion.[278][279] However, Indian aviation would struggle due to an economic slowdown and rising fuel and operation costs. This led to consolidation, buyouts and discontinuations. In 2007, Air Sahara and Air Deccan were acquired by Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines respectively. Paramount Airways ceased operations in 2010 and Kingfisher shut down in 2012. Etihad Airways agreed to acquire a 24% stake in Jet Airways in 2013. AirAsia India, a low-cost carrier operating as a joint venture between Air Asia and Tata Sons launched in 2014. As of 2013–14, only IndiGo and GoAir were generating profits.[280] The average domestic passenger air fare dropped by 70% between 2005 and 2017, after adjusting for inflation.[274]

Banking and financial services

The financial services industry contributed $809 billion (37% of GDP) and employed 14.17 million people (3% of the workforce) in 2016, and the banking sector contributed $407 billion (19% of GDP) and employed 5.5 million people (1% of the workforce) in 2016.[193] The Indian money market is classified into the organised sector, comprising private, public and foreign-owned commercial banks and cooperative banks, together known as 'scheduled banks'; and the unorganised sector, which includes individual or family-owned indigenous bankers or money lenders and non-banking financial companies.[281] The unorganised sector and microcredit are preferred over traditional banks in rural and sub-urban areas, especially for non-productive purposes such as short-term loans for ceremonies.[282]

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi nationalised 14 banks in 1969, followed by six others in 1980, and made it mandatory for banks to provide 40% of their net credit to priority sectors including agriculture, small-scale industry, retail trade and small business, to ensure that the banks fulfilled their social and developmental goals. Since then, the number of bank branches has increased from 8,260 in 1969 to 72,170 in 2007 and the population covered by a branch decreased from 63,800 to 15,000 during the same period. The total bank deposits increased from ₹59.1 billion (US$830 million) in 1970–71 to ₹38,309 billion (US$540 billion) in 2008–09. Despite an increase of rural branches – from 1,860 or 22% of the total in 1969 to 30,590 or 42% in 2007 – only 32,270 of 500,000 villages are served by a scheduled bank.[283][284]

India's gross domestic savings in 2006–07 as a percentage of GDP stood at a high 32.8%.[285] More than half of personal savings are invested in physical assets such as land, houses, cattle, and gold.[286] The government-owned public-sector banks hold over 75% of total assets of the banking industry, with the private and foreign banks holding 18.2% and 6.5% respectively.[287] Since liberalisation, the government has approved significant banking reforms. While some of these relate to nationalised banks – such as reforms encouraging mergers, reducing government interference and increasing profitability and competitiveness – other reforms have opened the banking and insurance sectors to private and foreign companies.[221][288]

Financial technology

According to the report of The National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM), India has a presence of around 400 companies in the fintech space, with an investment of about $420 million in 2015. The NASSCOM report also estimated the fintech software and services market to grow 1.7 times by 2020, making it worth $8 billion.[289] The Indian fintech landscape is segmented as follows – 34% in payment processing, followed by 32% in banking and 12% in the trading, public and private markets.[290]

Information technology

The information technology (IT) industry in India consists of two major components: IT Services and business process outsourcing (BPO). The sector has increased its contribution to India's GDP from 1.2% in 1998 to 7.5% in 2012.[291] According to NASSCOM, the sector aggregated revenues of US$147 billion in 2015, where export revenue stood at US$99 billion and domestic at US$48 billion, growing by over 13%.[291]

The growth in the IT sector is attributed to increased specialisation, and an availability of a large pool of low-cost, highly skilled, fluent English-speaking workers – matched by increased demand from foreign consumers interested in India's service exports, or looking to outsource their operations. The share of the Indian IT industry in the country's GDP increased from 4.8% in 2005–06 to 7% in 2008.[292] In 2009, seven Indian firms were listed among the top 15 technology outsourcing companies in the world.[293]

The business process outsourcing services in the outsourcing industry in India caters mainly to Western operations of multinational corporations. As of 2012, around 2.8 million people work in the outsourcing sector.[294] Annual revenues are around $11 billion,[294] around 1% of GDP. Around 2.5 million people graduate in India every year. Wages are rising by 10–15 percent as a result of skill shortages.[294]

Insurance

India became the tenth-largest insurance market in the world in 2013, rising from 15th in 2011.[295][296] At a total market size of US$66.4 billion in 2013, it remains small compared to world's major economies,[297] and the Indian insurance market accounted for just 2% of the world's insurance business in 2017. India's life and non-life insurance industry collected ₹6.10 lakh crore (US$86 billion) in total gross insurance premiums in 2018. Life insurance accounts for 75.41% of the insurance market and the rest is general insurance.[298] Of the 52 insurance companies in India, 24 are active in life-insurance business.[297]

Specialised insurers Export Credit Guarantee Corporation and Agriculture Insurance Company (AIC) offer credit guarantee and crop insurance. It has introduced several innovative products such as weather insurance and insurance related to specific crops. The premium underwritten by the non-life insurers during 2010–11 was ₹425 billion against ₹346 billion in 2009–10. The growth was satisfactory, particularly given across-the-broad cuts in the tariff rates. The private insurers underwrote premiums of ₹174 billion against ₹140 billion in 2009–10.

The Indian insurance business had been under-developed with low levels of insurance penetration.

Retail

The retail industry, excluding wholesale, contributed $482 billion (22% of GDP) and employed 249.94 million people (57% of the workforce) in 2016. The industry is the second largest employer in India, after agriculture.[193] The Indian retail market is estimated to be US$600 billion and one of the top-five retail markets in the world by economic value. India has one of the fastest-growing retail markets in the world,[299][300] and is projected to reach $1.3 trillion by 2020.[301][302] The e-commerce retail market in India was valued at $32.7 billion in 2018, and is expected to reach $71.9 billion by 2022.[303]

India's retail industry mostly consists of local mom-and-pop stores, owner-manned shops and street vendors. Retail supermarkets are expanding, with a market share of 4% in 2008.[304] In 2012, the government permitted 51% FDI in multi-brand retail and 100% FDI in single-brand retail. However, a lack of back-end warehouse infrastructure and state-level permits and red tape continue to limit growth of organised retail.[305] Compliance with over thirty regulations such as "signboard licences" and "anti-hoarding measures" must be made before a store can open for business. There are taxes for moving goods from state to state, and even within states.[304] According to The Wall Street Journal, the lack of infrastructure and efficient retail networks cause a third of India's agriculture produce to be lost from spoilage.[211]

Tourism

The World Travel & Tourism Council calculated that tourism generated ₹15.24 lakh crore (US$210 billion) or 9.4% of the nation's GDP in 2017 and supported 41.622 million jobs, 8% of its total employment. The sector is predicted to grow at an annual rate of 6.9% to ₹32.05 lakh crore (US$450 billion) by 2028 (9.9% of GDP).[306] Over 10 million foreign tourists arrived in India in 2017 compared to 8.89 million in 2016, recording a growth of 15.6%.[307] India earned $21.07 billion in foreign exchange from tourism receipts in 2015.[308] International tourism to India has seen a steady growth from 2.37 million arrivals in 1997 to 8.03 million arrivals in 2015. The United States is the largest source of international tourists to India, while European Union nations and Japan are other major sources of international tourists.[309][310] Less than 10% of international tourists visit the Taj Mahal, with the majority visiting other cultural, thematic and holiday circuits.[311] Over 12 million Indian citizens take international trips each year for tourism, while domestic tourism within India adds about 740 million Indian travellers.[309]

India has a fast-growing medical tourism sector of its health care economy, offering low-cost health services and long-term care.[312][313] In October 2015, the medical tourism sector was estimated to be worth US$3 billion. It is projected to grow to $7–8 billion by 2020.[314] In 2014, 184,298 foreign patients traveled to India to seek medical treatment.[315]

Media and entertainment industry

An ASSOCHAM-PwC joint study projected that the Indian media and entertainment industry would grow from a size of $30.364 billion in 2017 to $52.683 billion by 2022, recording a CAGR of 11.7%. The study also predicted that television, cinema and over-the-top services would account for nearly half of the overall industry growth during the period.[316]

Healthcare

India's healthcare sector is expected to grow at a CAGR of 29% between 2015 and 2020, to reach US$280 billion, buoyed by rising incomes, greater health awareness, increased precedence of lifestyle diseases, and improved access to health insurance.[264]

The ayurveda industry in India recorded a market size of $4.4 billion in 2018. The Confederation of Indian Industry estimates that the industry will grow at a CAGR 16% until 2025. Nearly 75% of the market comprises over-the-counter personal care and beauty products, while ayurvedic well-being or ayurvedic tourism services accounted for 15% of the market.[317]

Logistics

The logistics industry in India was worth over $160 billion in 2016, and grew at a CAGR of 7.8% in the previous five-year period. The industry employs about 22 million people.[318][319] It is expected to reach of a size of $215 billion by 2020.[320] India was ranked 35th out of 160 countries in the World Bank's 2016 Logistics Performance Index.[321]

Printing

Telecommunications

The telecommunication sector generated ₹2.20 lakh crore (US$31 billion) in revenue in 2014–15, accounting for 1.94% of total GDP.[322] India is the second-largest market in the world by number of telephone users (both fixed and mobile phones) with 1.053 billion subscribers as of 31 August 2016. It has one of the lowest call-tariffs in the world, due to fierce competition among telecom operators. India has the world's third-largest Internet user-base. As of 31 March 2016, there were 342.65 million Internet subscribers in the country.[323]

Industry estimates indicate that there are over 554 million TV consumers in India as of 2012.[324] India is the largest direct-to-home (DTH) television market in the world by number of subscribers. As of May 2016, there were 84.80 million DTH subscribers in the country.[325]

Mining and Construction

Mining

Mining contributed $63 billion (3% of GDP) and employed 20.14 million people (5% of the workforce) in 2016.[193] India's mining industry was the fourth-largest producer of minerals in the world by volume, and eighth-largest producer by value in 2009.[326] In 2013, it mined and processed 89 minerals, of which four were fuel, three were atomic energy minerals, and 80 non-fuel.[327] The government-owned public sector accounted for 68% of mineral production by volume in 2011–12.[328]

Nearly 50% of India's mining industry, by output value, is concentrated in eight states: Odisha, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. Another 25% of the output by value comes from offshore oil and gas resources.[328] India operated about 3,000 mines in 2010, half of which were coal, limestone and iron ore.[329] On output-value basis, India was one of the five largest producers of mica, chromite, coal, lignite, iron ore, bauxite, barite, zinc and manganese; while being one of the ten largest global producers of many other minerals.[326][328] India was the fourth-largest producer of steel in 2013,[330] and the seventh-largest producer of aluminium.[331]

India's mineral resources are vast.[332] However, its mining industry has declined – contributing 2.3% of its GDP in 2010 compared to 3% in 2000, and employed 2.9 million people – a decreasing percentage of its total labour. India is a net importer of many minerals including coal. India's mining sector decline is because of complex permit, regulatory and administrative procedures, inadequate infrastructure, shortage of capital resources, and slow adoption of environmentally sustainable technologies.[328][333]

Iron and steel

In fiscal year 2014–15, India was the third-largest producer of raw steel[334] and the largest producer of sponge iron. The industry produced 91.46 million tons of finished steel and 9.7 million tons of pig iron. Most iron and steel in India is produced from iron ore.[335]

Construction

The construction industry contributed $288 billion (13% of GDP) and employed 60.42 million people (14% of the workforce) in 2016.[193]

Foreign trade and investment

Foreign trade

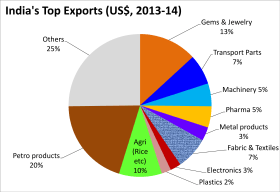

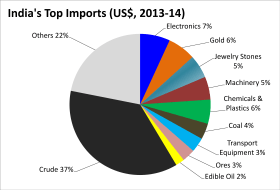

Until the liberalisation of 1991, India was largely and intentionally isolated from world markets, to protect its economy and to achieve self-reliance. Foreign trade was subject to import tariffs, export taxes and quantitative restrictions, while foreign direct investment (FDI) was restricted by upper-limit equity participation, restrictions on technology transfer, export obligations and government approvals; these approvals were needed for nearly 60% of new FDI in the industrial sector. The restrictions ensured that FDI averaged only around $200 million annually between 1985 and 1991; a large percentage of the capital flows consisted of foreign aid, commercial borrowing and deposits of non-resident Indians.[336] India's exports were stagnant for the first 15 years after independence, due to general neglect of trade policy by the government of that period; imports in the same period, with early industrialisation, consisted predominantly of machinery, raw materials and consumer goods.[337] Since liberalisation, the value of India's international trade has increased sharply,[338] with the contribution of total trade in goods and services to the GDP rising from 16% in 1990–91 to 47% in 2009–10.[339][340] Foreign trade accounted for 48.8% of India's GDP in 2015.[17] Globally, India accounts for 1.44% of exports and 2.12% of imports for merchandise trade and 3.34% of exports and 3.31% of imports for commercial services trade.[340] India's major trading partners are the European Union, China, the United States and the United Arab Emirates.[341] In 2006–07, major export commodities included engineering goods, petroleum products, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, gems and jewellery, textiles and garments, agricultural products, iron ore and other minerals. Major import commodities included crude oil and related products, machinery, electronic goods, gold and silver.[342] In November 2010, exports increased 22.3% year-on-year to ₹851 billion (US$12 billion), while imports were up 7.5% at ₹1,251 billion (US$18 billion). The trade deficit for the same month dropped from ₹469 billion (US$6.6 billion) in 2009 to ₹401 billion (US$5.6 billion) in 2010.[343]

India is a founding-member of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the WTO. While participating actively in its general council meetings, India has been crucial in voicing the concerns of the developing world. For instance, India has continued its opposition to the inclusion of labour, environmental issues and other non-tariff barriers to trade in WTO policies.[344]

Balance of payments

Since independence, India's balance of payments on its current account has been negative. Since economic liberalisation in the 1990s, precipitated by a balance-of-payment crisis, India's exports rose consistently, covering 80.3% of its imports in 2002–03, up from 66.2% in 1990–91.[346] However, the global economic slump followed by a general deceleration in world trade saw the exports as a percentage of imports drop to 61.4% in 2008–09.[347] India's growing oil import bill is seen as the main driver behind the large current account deficit,[348] which rose to $118.7 billion, or 11.11% of GDP, in 2008–09.[349] Between January and October 2010, India imported $82.1 billion worth of crude oil.[348] The Indian economy has run a trade deficit every year from 2002 to 2012, with a merchandise trade deficit of US$189 billion in 2011–12.[350] Its trade with China has the largest deficit, about $31 billion in 2013.[351]

India's reliance on external assistance and concessional debt has decreased since liberalisation of the economy, and the debt service ratio decreased from 35.3% in 1990–91 to 4.4% in 2008–09.[352] In India, external commercial borrowings (ECBs), or commercial loans from non-resident lenders, are being permitted by the government for providing an additional source of funds to Indian corporates. The Ministry of Finance monitors and regulates them through ECB policy guidelines issued by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under the Foreign Exchange Management Act of 1999.[353] India's foreign exchange reserves have steadily risen from $5.8 billion in March 1991 to ₹38,832.21 billion (US$540 billion) in July 2020.[76][354] In 2012, the United Kingdom announced an end to all financial aid to India, citing the growth and robustness of Indian economy.[355][356]

India's current account deficit reached an all-time high in 2013.[357] India has historically funded its current account deficit through borrowings by companies in the overseas markets or remittances by non-resident Indians and portfolio inflows. From April 2016 to January 2017, RBI data showed that, for the first time since 1991, India was funding its deficit through foreign direct investment inflows. The Economic Times noted that the development was "a sign of rising confidence among long-term investors in Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ability to strengthen the country's economic foundation for sustained growth".[358]

Foreign direct investment

| Rank | Country | Inflows (million US$) | Inflows (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mauritius | 50,164 | 42.00 |

| 2 | Singapore | 11,275 | 9.00 |

| 3 | US | 8,914 | 7.00 |

| 4 | UK | 6,158 | 5.00 |

| 5 | Netherlands | 4,968 | 4.00 |

As the third-largest economy in the world in PPP terms, India has attracted foreign direct investment (FDI).[360] During the year 2011, FDI inflow into India stood at $36.5 billion, 51.1% higher than the 2010 figure of $24.15 billion. India has strengths in telecommunication, information technology and other significant areas such as auto components, chemicals, apparels, pharmaceuticals, and jewellery. Despite a surge in foreign investments, rigid FDI policies[361] were a significant hindrance. Over time, India has adopted a number of FDI reforms.[360] India has a large pool of skilled managerial and technical expertise. The size of the middle-class population stands at 300 million and represents a growing consumer market.[362]

India liberalised its FDI policy in 2005, allowing up to a 100% FDI stake in ventures. Industrial policy reforms have substantially reduced industrial licensing requirements, removed restrictions on expansion and facilitated easy access to foreign technology and investment. The upward growth curve of the real-estate sector owes some credit to a booming economy and liberalised FDI regime. In March 2005, the government amended the rules to allow 100% FDI in the construction sector, including built-up infrastructure and construction development projects comprising housing, commercial premises, hospitals, educational institutions, recreational facilities, and city- and regional-level infrastructure.[363] Between 2012 and 2014, India extended these reforms to defence, telecom, oil, retail, aviation, and other sectors.[364][365]

From 2000 to 2010, the country attracted $178 billion as FDI.[366] The inordinately high investment from Mauritius is due to routing of international funds through the country given significant tax advantages – double taxation is avoided due to a tax treaty between India and Mauritius, and Mauritius is a capital gains tax haven, effectively creating a zero-taxation FDI channel.[367] FDI accounted for 2.1% of India's GDP in 2015.[17]

As the government has eased 87 foreign investment direct rules across 21 sectors in the last three years, FDI inflows hit $60.1 billion between 2016 and 2017 in India.[368][369]

Outflows

Since 2000, Indian companies have expanded overseas, investing FDI and creating jobs outside India. From 2006 to 2010, FDI by Indian companies outside India amounted to 1.34 per cent of its GDP.[370] Indian companies have deployed FDI and started operations in the United States,[371] Europe and Africa.[372] The Indian company Tata is the United Kingdom's largest manufacturer and private-sector employer.[373][374]

Remittances

In 2015, a total of US$68.91 billion was made in remittances to India from other countries, and a total of US$8.476 billion was made in remittances by foreign workers in India to their home countries. The UAE, the US, and Saudi Arabia were the top sources of remittances to India, while Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal were the top recipients of remittances from India.[375] Remittances to India accounted for 3.32% of the country's GDP in 2015.[17]

Mergers and Acquisitions

Between 1985 and 2018 20,846 deals have been announced in, into (inbound) and out of (outbound) India. This cumulates to a value of US$618 billion. In terms of value, 2010 has been the most active year with deals worth almost 60 bil. USD. Most deals have been conducted in 2007 (1,510).[376]

Here is a list of the top 10 deals with Indian companies participating:

| Acquiror Name | Acquiror Mid Industry | Acquiror Nation | Target Name | Target Mid Industry | Target Nation | Value of Transaction ($mil) |

| Petrol Complex Pte Ltd | Oil & Gas | Singapore | Essar Oil Ltd | Oil & Gas | India | 12,907.25 |

| Vodafone Grp Plc | Wireless | United Kingdom | Hutchison Essar Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | 12,748.00 |

| Vodafone Grp PLC-Vodafone Asts | Wireless | India | Idea Cellular Ltd-Mobile Bus | Wireless | India | 11,627.32 |

| Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | MTN Group Ltd | Wireless | South Africa | 11,387.52 |

| Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | Zain Africa BV | Wireless | Nigeria | 10,700.00 |

| BP PLC | Oil & Gas | United Kingdom | Reliance Industries Ltd-21 Oil | Oil & Gas | India | 9,000.00 |

| MTN Group Ltd | Wireless | South Africa | Bharti Airtel Ltd | Wireless | India | 8,775.09 |

| Shareholders | Other Financials | India | Reliance Inds Ltd-Telecom Bus | Telecommunications Services | India | 8,063.01 |

| Oil & Natural Gas Corp Ltd | Oil & Gas | India | Hindustan Petro Corp Ltd | Petrochemicals | India | 5,784.20 |

| Reliance Commun Ventures Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | Reliance Infocomm Ltd | Telecommunications Services | India | 5,577.18 |

Currency

| Year | INR₹ per US$ (average annual)[377] |

|---|---|

| 1975 | 9.4058 |

| 1980 | 7.8800 |

| 1985 | 12.3640 |

| 1990 | 17.4992 |

| 1995 | 32.4198 |

| 2000 | 44.9401 |

| 2005 | 44.1000 |

| 2010 | 45.7393 |

| 2015 | 64.05 |

| 2016 | 67.09 |

| 2017 | 64.14 |

| 2018 | 69.71 |

The Indian rupee (₹) is the only legal tender in India, and is also accepted as legal tender in neighbouring Nepal and Bhutan, both of which peg their currency to that of the Indian rupee. The rupee is divided into 100 paisas. The highest-denomination banknote is the ₹2,000 note; the lowest-denomination coin in circulation is the 50 paise coin.[378] Since 30 June 2011, all denominations below 50 paise have ceased to be legal currency.[379][380] India's monetary system is managed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country's central bank.[381] Established on 1 April 1935 and nationalised in 1949, the RBI serves as the nation's monetary authority, regulator and supervisor of the monetary system, banker to the government, custodian of foreign exchange reserves, and as an issuer of currency. It is governed by a central board of directors, headed by a governor who is appointed by the Government of India.[382] The benchmark interest rates are set by the Monetary Policy Committee.

The rupee was linked to the British pound from 1927 to 1946, and then to the US dollar until 1975 through a fixed exchange rate. It was devalued in September 1975 and the system of fixed par rate was replaced with a basket of four major international currencies: the British pound, the US dollar, the Japanese yen and the Deutsche Mark.[383] In 1991, after the collapse of its largest trading partner, the Soviet Union, India faced the major foreign exchange crisis and the rupee was devalued by around 19% in two stages on 1 and 2 July. In 1992, a Liberalized Exchange Rate Mechanism (LERMS) was introduced. Under LERMS, exporters had to surrender 40 percent of their foreign exchange earnings to the RBI at the RBI-determined exchange rate; the remaining 60% could be converted at the market-determined exchange rate. In 1994, the rupee was convertible on the current account, with some capital controls.[384]

After the sharp devaluation in 1991 and transition to current account convertibility in 1994, the value of the rupee has been largely determined by market forces. The rupee has been fairly stable during the decade 2000–2010. In October 2018, rupee touched an all-time low 74.90 to the US dollar.[385]

Income and consumption

India's gross national income per capita had experienced high growth rates since 2002. It tripled from ₹19,040 in 2002–03 to ₹53,331 in 2010–11, averaging 13.7% growth each of these eight years, with peak growth of 15.6% in 2010–11.[387] However growth in the inflation-adjusted per-capita income of the nation slowed to 5.6% in 2010–11, down from 6.4% in the previous year. These consumption levels are on an individual basis.[388] The average family income in India was $6,671 per household in 2011.[389]

According to 2011 census data, India has about 330 million houses and 247 million households. The household size in India has dropped in recent years, the 2011 census reporting 50% of households have four or fewer members, with an average 4.8 members per household including surviving grandparents.[390][391] These households produced a GDP of about $1.7 trillion.[392] Consumption patterns note: approximately 67% of households use firewood, crop residue or cow-dung cakes for cooking purposes; 53% do not have sanitation or drainage facilities on premises; 83% have water supply within their premises or 100 metres (330 ft) from their house in urban areas and 500 metres (1,600 ft) from the house in rural areas; 67% of the households have access to electricity; 63% of households have landline or mobile telephone service; 43% have a television; 26% have either a two- or four-wheel motor vehicle. Compared to 2001, these income and consumption trends represent moderate to significant improvements.[390] One report in 2010 claimed that high-income households outnumber low-income households.[393]

_per_capita_in_2016.png)

New World Wealth publishes reports tracking the total wealth of countries, which is measured as the private wealth held by all residents of a country. According to New World Wealth, India's total wealth increased from $3,165 billion in 2007 to $8,230 billion in 2017, a growth rate of 160%. India's total wealth decreased by 1% from $8.23 trillion in 2017 to $8.148 trillion in 2018, making it the sixth wealthiest nation in the world. There are 20,730 multimillionaires (7th largest in the world)[395] and 118 billionaires in India (3rd largest in the world). With 327,100 high net-worth individuals (HNWI), India is home to the 9th highest number of HNWIs in the world. Mumbai is the wealthiest Indian city and the 12th wealthiest in the world, with a total net worth of $941 billion in 2018. Twenty-eight billionaires reside in the city, ranked ninth worldwide.[396] As of December 2016, the next wealthiest cities in India were Delhi ($450 billion), Bangalore ($320 billion), Hyderabad ($310 billion), Kolkata ($290 billion), Chennai ($150 billion) and Gurgaon ($110 billion).[397][398]