Cockade of Italy

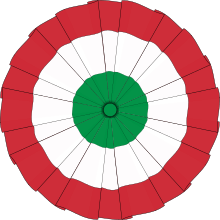

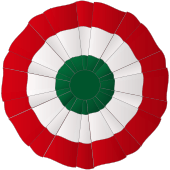

The cockade of Italy (Italian: Coccarda italiana tricolore) is the national ornament of Italy, obtained by folding a green, white and red ribbon into a plissé using the technique called "plissage" (pleating). It is one of the national symbols of Italy and is composed of the three colors of the Italian flag with the green in the center, the white immediately outside and the red on the edge: this convention on the position of colors derives from the cockades used in Bologna in 1794 during an attempt of revolt, which had this chromatic composition.[1] The cockade with the red and green inverted position is instead that of Iran.[2]

The Italian tricolor cockade appeared for the first time in Genoa on 21 August 1789,[3] and with it the colors of the three Italian national colors,[3] anticipating by seven years the first tricolor military banner, which was adopted by the Lombard Legion on 11 October 1796,[4] and of eight years the birth of the flag of Italy, which had its origins on 7 January 1797, when it became for the first time a national flag of an Italian sovereign State, the Cispadane Republic.[5] The hypotheses that consider the birth of the three Italian national colors ascribable to the medieval or Renaissance period, or linked to Freemasonry, are rejected by historians.[6][7]

The green, white and red applied to a tricolor cockade reappeared during the failed uprising of Bologna against the Papal States of 13–14 November 1794 by Luigi Zamboni and Giovanni Battista De Rolandis.[8][9] On 14 June 1848, it replaced the azure cockade on the uniforms of some departments of the Royal Sardinian Army (become Royal Italian Army in 1861), while on 1 January 1948, with the birth of the Italian Republic, it took its place as a national ornament.[10]

The Italian tricolor cockade is one of the symbols of the Italian Air Force and one of its fabric reproductions is sewn onto the meshes of the sports teams holding the Italian Cups which are organized in various national team sports.

History

The birth of the three Italian colors on a cockade

During the French revolution, the red, white and blue tricolor cockade was adopted, among other symbols, which contributed to the affirmation of the three colors on the heraldic symbols of the French nobles, becoming synonymous with change; for some years, all over Europe, those who wore a cockade were therefore viewed with great suspicion. Later the meaning of change assigned to the French tricolor cockade crossed the Alps and arrived in Italy together with the use of the cockade and all the baggage of values of the French revolution, which were perpetrated by the Jacobinism of the origins, including the ideals of social renewal - on the basis of the advocacy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 - and subsequently also political, with the first patriotic ferments directed at national self-determination which subsequently led, on the Italian peninsula, to the Risorgimento.[11][12][13]

The first sporadic demonstrations in favor of the ideals of the French revolution, by the Italian population, took place in August 1789 with the appearance, especially in the Papal States, of cockades of makeshift constituted by simple green leaves of trees, which were pinned on the clothes of the protesters recalling similar protests in France at the dawn of the revolution shortly before the adoption of the blue, white and red tricolor.[14] On 12 July 1789, two days before the storming of the Bastille, the revolutionary journalist Camille Desmoulins, while hailing the Parisian crowd to revolt, asked the protesters what color to adopt as a symbol of the French revolution, proposing the green hope or the blue of the American revolution, symbol of freedom and democracy: the protesters replied "The green! The green! We want green cockades!"[15] Desmoulins then seized a green leaf from the ground and pointed it to the hat as a distinctive sign of the revolutionaries.[15]

The green, in the primitive French cockade, was immediately abandoned in favor of blue and red, or the ancient colors of Paris, because it was also the color of the king's brother, Count of Artois, who became monarch after the First Restoration with the name of Charles X of France.[16] The French tricolor cockade was then completed on 17 July 1789 with the addition of white, the color of the House of Bourbon, in deference to King Louis XVI of France, who was still ruling despite the violent revolts that raged in the country: the French monarchy was in fact abolished later, on 10 August 1792.

Later the Italian population began to use real cockades made of cloth: the green of the leaves of the trees already used previously, were added white and red so as to recall in a more marked way the revolutionary ideals represented by the French tricolor.[17] The first documented trace of the use of Italian national colors is dated 21 August 1789: in the historical archives of the Republic of Genoa it is reported that eyewitnesses had seen some demonstrators pinned on their clothes hanging a red, white and green cockade on their clothes.[3]

The Italian gazettes of the time had in fact created confusion about the facts of French revolution, especially on the replacement of green with blue and red, reporting the news that the French tricolor was green, white and red.[17] The green was then maintained by the Italian Jacobins because it represented nature and therefore - metaphorically - also natural rights, or social equality and freedom.[18]

The tricolor cockade becomes one of the National symbols of Italy

Later the green, white and red cockade always spread to a greater extent, gradually becoming the only ornament used in Italy by the rioters.[14] The patriots began to call it "Italian cockade" making it become one of the symbols of the country.[14] In fact, the error of journalistic headings on the colors of the French tricolor cockade was clarified, and consequently the connotations of uniqueness were assumed, green, white and red were adopted by the Risorgimento patriots as one of the most important symbols of the insurrectional and political struggle, aimed at completing the national unit taking the name of "Italian tricolor".[14] The green, white and red tricolor thus acquired a strong patriotic value, becoming one of the symbols of national awareness, a change that gradually led it to enter the collective imagination of the Italians.[14]

The Italian tricolor cockade, as well as all the similar ornaments made in the same period also in other countries, had as its main characteristic that it could be clearly visible, thus giving way to unequivocally identify the political ideas of the person who wore it, as well as to be, if necessary, better hidden than, for example, a flag.[19]

The use of the Italian tricolor was not limited to the presence of green, white and red in a cockade: the latter, having been born on 21 August 1789, heralded by seven years the first tricolor war flag, which was chosen by the Lombard Legion on 11 October 1796,[4] which is associated with the first official approval of the Italian national colors by the authorities, in this case Napoleon, and eight years the adoption of the flag of Italy, which was born on 7 January 1797, when it first assumed the role of the national banner of a sovereign Italian state, the Cispadane Republic.[5]

The subsequent adoption by the Italian patriots of the green, white and red tricolor was immediate, unambiguous and devoid of political contrasts: in France the opposite happened, since the French tricolor was taken as a symbol first by the Republicans and then by the Bonapartists, that they were in antagonism with the Monarchists and the Catholics, who had the royal white flag with the fleur-de-lis of France as their reference flag.[18]

The cockade of the Bologna revolt

From a historical perspective, given the judicial process and the clamor that followed, were the tricolor cockades made in 1794 by two students of the University of Bologna, Luigi Zamboni from Bologna and Giovanni Battista De Rolandis from Asti, who placed themselves at the head of an insurrectional attempt to free Bologna from papal rule; in addition to the two students there were also two medical doctors, Antonio Succi and Angelo Sassoli, who then betrayed the patriots by referring everything to the papal police, and four other people (Giuseppe Rizzoli, known as Dozza, Camillo Tomesani, twisted neck, Antonio Forni Mago Sabino and Camillo Galli).[20] Luigi Zamboni had previously expressed the desire to create a tricolor flag that would become the flag of a united Italy.[21]

During this revolt attempt, which took place between 13 and 14 November 1794 (or, according to other sources, 13 December 1794),[21] the demonstrators led by De Rolandis and Zamboni flaunted a red and white cockade (which are also the colors of the municipal coat of arms of Bologna) having a green lining.[21] These cockades were made by Zamboni's parents, who made the tradesmen by trade and then paid dearly for this initiative.[21] These cockades had green in the center, white immediately outside and red on the edge.[1]

During the recruitment work, De Rolandis and Zamboni managed to convince thirty people to participate in their attempt at insurrection [27]. The two, to carry out the attempted revolt, purchased some firearms which later proved to be of poor quality.[21] The goal was to spread a leaflet intended to give rise to Bologna and Castel Bolognese, proclaiming that there was no effect whatsoever.[21]

After failing to raise the city, the revolutionaries tried to take refuge in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, but the local police first captured them in Covigliaio and then handed them over to the papal authorities; after the capture of the fugitives, the latter launched an action "Super complocta et seditiosa compositione destributa per civitatem in conventicula armata" (a prosecution for fomenting armed treasonous conspiracy throughout the state) at the Tribunale del Torrone (the Inquisition of Bologna). The trial involved all the participants in the insurrectional attempt, the family of Zamboni and the Succi brothers.[22]

Zamboni was found dead in a cell nicknamed "Inferno" ("Hell"), which he shared with two common criminals, probably killed by them on the orders of the police or perhaps suicide after an unsuccessful attempt to escape,[23] on 18 August 1795 (other hypotheses they actually want it to be a murder whose principals are to be found in some senatorial Bolognese families, in the Savioli family in particular).[24]

De Rolandis was publicly executed, after being subjected to interrogation preceded and followed by ferocious torture,[25] on 26 April 1796.[23] Zamboni's father died of heart almost eighty years after suffering terrible torture, while his mother was first whipped through the streets of Bologna and then sentenced to life imprisonment.[23] The other defendants, where they had minor penalties,[22] were freed shortly thereafter by the French, who in the meantime had invaded Emilia driving out the pontiffs.[23] The bodies of De Rolandis and Zamboni were then solemnly buried in Bologna in the Giardino della Montagnola on the direct order of Napoleon,[26] before being dispersed in 1799 with the arrival of the Austrians.[23]

Of the original cockades of Zamboni and De Rolandis, only one has come down to us.[1] The historic cockade, which is owned by the De Rolandis family, has been exhibited for some time in the National Museum of the Italian Risorgimento in Turin.[1] In 2006, during some renovations, it was transferred to the European Student Museum of the University of Bologna, where it is still preserved.[1]

The tricolor cockade appeared, after the events of Bologna, during Napoleon's entry into Milan, which took place on 15 May 1796.[27] These cockades, having the typical circular shape, possessed red on the outside, green on an intermediate position and white on the center.[28] These ornaments were worn by the rioters even during the religious ceremonies officiated inside the Milan Cathedral as thanks for the arrival of Napoleon, who was seen, at least initially, as a liberator.[27] The tricolor cockades then became one of the official symbols of the Milanese National Guard, which was founded on 20 November 1796, and then spread elsewhere along the Italian peninsula.[18]

Color position

The Italian tricolor cockade, by convention, has the green in the center, the white in an intermediate position and the peripheral red: this custom derives from one of the conceptual characteristics of the cockades, which can be imagined as flags rolled around the flagpole seen from above.[29]

In the case of the Italian tricolor cockade, the green is located in the center because in the flag of Italy this color is the one closest to the flagpole.[29] The tricolor cockades with red and green inverted position are those of Iran[2] and Suriname.[30]

The Hungarian cockade has the same arrangement of colors as the Italian tricolor cockade: having the color position reversed like the Iranian cockade and the Surinamese one is an urban legend.[31]

Other cockades identical to the Italian one, even in the arrangement of the colors, are the national ornaments of Burundi, Mexico, Lebanon, Seychelles, Algeria and Turkmenistan.[30] The national ornament of Bulgaria and Maldives (both of which are, starting from the center, white, green and red) and Madagascar (which is, starting from the center, white, red and green).[30]

Use

Institutions and aeronautics

It is tradition, for the highest offices of the Italian State, excluding the President of the Italian Republic, to have pinned on the jacket, during the military parade of the Festa della Repubblica, which is celebrated every 2 June, a tricolor cockade.[32]

On the Italian planes used during the First World War, with the use of coloring the underside of the lower wing with green, white and red sections for the recognition of the nationality, in 1917, they began to appear on the fuselages and on the wings of the tricolor circular cockades which, in some cases, had the green perimeter and the red central disk, therefore with a position of the colors which was the inverse of that conventionally used then for the Italian tricolor cockade.

The Italian tricolor cockade was used, on the airplanes, in a discontinuous way, until 1927, when it was replaced by a rosette depicting the lictor's fasces, one of the most identifying symbols of fascism.[33] In aeronautics the tricolor cockade with the red towards the outside and the green at the center is back in use, without being changed, in 1943, during the World War II,[34] on the occasion of the constitution of the Italian Co-belligerent Air Force: after the fall of fascism in Italy, there was in fact the immediate disappearance of all the symbols linked to it, including the lictor's fasces.[34]

The tricolor cockade, which was then widely used on all Italian state aircraft, not only military,[35] is still today one of the symbols of the Italian Air Force.[36]

Sport

In Italian sport, following a tradition born in football in the late fifties of the 20th century[37] (and reflecting the praxis of the scudetto, which debuted on the Genoa C.F.C. jerseys in the 1924-1925 season based on an idea by Gabriele D'Annunzio,[38]) the tricolor cockade has become the distinctive symbol of the successes in the national cups, sewn on the jersey of the team holding the trophy: the winning formations in the various Italian Cups can in fact show off the cockade on their uniforms for the entire season following the victory.

The Italian tricolor cockade made its debut in football in the 1958-1959 season on S.S. Lazio shirts.[39] In football, starting from the 1985-1986 season, the cockade used for the teams holding the Coppa Italia underwent a change: the version with the inverted colors began to be used, that is with the green outside and the red in the center. From the 2006-2007 season the original typology was restored, the one used by Zamboni and De Rolandis in 1794 during the revolt attempt in Bologna, with the red outside and the green in the center. In football, the cockade is also a symbol of the victories in the Coppa Italia Serie D, in the Coppa Italia Dilettanti and - with substantial stylistic differences - in the Coppa Italia Serie C.[40]

Italian azure cockade

.tiff.jpg)

The Italian azure cockade was one of the representative ornaments of Italy, obtained by circularly pleating an azure ribbon. Coming from the Savoy blue, the color of the Italian royal family from 1861 to 1946, the azure cockade remained officially in use until 1 January 1948, when the constitution of the Italian Republic came into force, after which it was replaced, in all official offices, from the Italian tricolor cockade.

The azure cockade has its origins at least in the 17th century, as evidenced by some documents, which confirm its presence on military uniforms in use at the time of Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia.[41] Other sources testify to its use even in the 18th century.[42]

The Albertine Statute of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was promulgated on 4 March 1848 and which later became the fundamental law of the Kingdom of Italy, foresaw that the azure cockade was the only national one. In this way the azure, historical color of the Kingdom of Sardinia and even before the Duchy of Savoy, was kept alongside the tricolor cockade, which was born in 1789 and which was instead very common among the population.[43][44]

On 14 June 1848, during the First Italian War of Independence, a circulaire from the Ministry of War decreed the replacement of the azure cockade, which until then had been placed on the hat of the uniform of the Carabinieri, with "the cockade to the three Italian national colors in accordance with the established models".[45] This was not an exception: similarly the tricolor cockade replaced the azure one, for example, on the frieze of the Bersaglieri caps and on the headdresses of the soldiers of the cavalry regiments.[45][46][47] On the hat of the Carabinieri the azure cockade was present since the founding of the weapon, which is dated 1814,[48] while for the cavalry weapon its introduction can be ascribed to 1843,[49]

The azure cockade was instead used during the Sardinian campaign in central Italy in 1860, the siege of Gaeta (also dated 1860), the repression of post-unitary brigandage (1860-1870) and the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), in all cases pinned on the uniforms of the generals and that of the officers of the Royal Italian Army.[50]

The blue cockade was officially in use until 1 January 1948, when the Constitution of the Italian Republic came into force, being replaced, in all official locations, by the Italian tricolor cockade.

Citations

- "La Coccarda alla Biblioteca Museo Risorgimento" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "Renata Polverini: coccarde tricolori alla sua giunta ma i colori sono invertiti – Il Messaggero" (in Italian). Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 662.

- "L'Esercito del primo Tricolore" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "I simboli della Repubblica" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Fiorini, 1897 & pp. 244-247.

- Fiorini, 1897 & pp. 265-266.

- "Mostra Giovan Battista De Rolandis e il Tricolore" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 12.

- "Le origini della bandiera italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 156.

- Fiorini, 1897 & pp. 239-267 and 676-710.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 654–680.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 668.

- "Giovani del terzo millennio, di Giacomo Bolzano" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- "Il verde no, perché è il colore del re. Così la Francia ha scelto la bandiera blu, bianca e rossa ispirandosi all'America" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 666.

- "I valori - Il Tricolore" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "La politica dei colori nell'Italia contemporanea" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Fiorini, 1897 & p. 249.

- Colangeli, 1965 & p. 11.

- Fiorini, 1897 & p. 253.

- Colangeli, 1965 & p. 12.

- Poli, 2000 & p. 423.

- "La sommossa di Bologna" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Cronologia della nascita della Bandiera Nazionale Italiana sulla base dei fatti accaduti in seguito alla sommossa bolognese del 1794" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 10.

- Colangeli, 1965 & p. 13.

- Rivista aeronautica, 1990 & p. 115.

- "Roundels of the World" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- "Festa nazionale con diverse coccarde" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "2 giugno, gli applausi per Mattarella e Conte all'Altare della Patria" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Seconda Guerra Mondiale - Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Prima Guerra Mondiale - Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "San Felice, escursionista di Gaeta ferito mentre scende dal Picco di Circe" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Il contributo dell'Aeronautica Militare" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "Quando scudetto e coccarda sono sulla stessa maglia..." passionemaglie.it. 4 January 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- "150 anni di D'Annunzio, l'ideatore dello scudetto sulle maglie da gioco" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Albo d'oro – Storia della Coppa Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Storia Coppa Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Conosci Torino?" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Le uniformi da Vittorio Amedeo II a Carlo Emanuele III" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Le origini della bandiera italiana".

- "Il Tricolore".

- "La bandiera - Cenni storici e norme per l'esposizione" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Il cappello piumato" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Il contributo della Cavalleria all'Unità d'Italia" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "13 luglio 1814: nasce il corpo dei Carabinieri" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "Regolamenti su uniformi, equipaggiamento e armi" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- "I Savoia e il Massacro del Sud" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 August 2018.

References

- "Una gara non giocata ?". Rivista aeronautica (in Italian). 66. 1990.

- Alegi, Gregory (2001). Italian National Markings. Albatros Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-902207-33-5.

- Colangeli, Oronzo (1965). Simboli e bandiere nella storia del Risorgimento italiano (PDF) (in Italian). Patron. SBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0395583.

- Fiorini, Vittorio (1897). "Le origini del tricolore italiano". Nuova Antologia di scienze lettere e arti (in Italian). LXVII (fourth series): 239–267 and 676–710. SBN IT\ICCU\UBO\3928254.

- Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2.

- Poli, Marco (2000). "Brigida Borghi Zamboni, la madre dell'eroe. Per una rilettura del caso Zamboni-De Rolandis". Strenna storica bolognese (in Italian). anno L: 415–450. ISBN 88-555-2567-0.

- Villa, Claudio (2010). I simboli della Repubblica: la bandiera tricolore, il canto degli italiani, l'emblema (in Italian). Comune di Vanzago. SBN IT\ICCU\LO1\1355389.

- Viola, Orazio (1905). Il tricolore italiano (in Italian). Libreria Editrice Concetto Battiato. ISBN 978-1-161-20869-6.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cockades of Italy. |

.jpg)