Grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus Vitis.

Grapes can be eaten fresh as table grapes or they can be used for making wine, jam, grape juice, jelly, grape seed extract, raisins, vinegar, and grape seed oil. Grapes are a non-climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 288 kJ (69 kcal) |

18.1 g | |

| Sugars | 15.48 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.9 g |

0.16 g | |

0.72 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 6% 0.069 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 6% 0.07 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 1% 0.188 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 1% 0.05 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 7% 0.086 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 1% 2 μg |

| Choline | 1% 5.6 mg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3.2 mg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.19 mg |

| Vitamin K | 14% 14.6 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 10 mg |

| Iron | 3% 0.36 mg |

| Magnesium | 2% 7 mg |

| Manganese | 3% 0.071 mg |

| Phosphorus | 3% 20 mg |

| Potassium | 4% 191 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 2 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.07 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 81 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

History

The cultivation of the domesticated grape began 6,000–8,000 years ago in the Near East.[1] Yeast, one of the earliest domesticated microorganisms, occurs naturally on the skins of grapes, leading to the discovery of alcoholic drinks such as wine. The earliest archeological evidence for a dominant position of wine-making in human culture dates from 8,000 years ago in Georgia.[2][3][4]

The oldest known winery was found in Armenia, dating to around 4000 BC.[5] By the 9th century AD the city of Shiraz was known to produce some of the finest wines in the Middle East. Thus it has been proposed that Syrah red wine is named after Shiraz, a city in Persia where the grape was used to make Shirazi wine.[6]

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics record the cultivation of purple grapes, and history attests to the ancient Greeks, Phoenicians, and Romans growing purple grapes both for eating and wine production.[7] The growing of grapes would later spread to other regions in Europe, as well as North Africa, and eventually in North America.

In North America, native grapes belonging to various species of the genus Vitis proliferate in the wild across the continent, and were a part of the diet of many Native Americans, but were considered by early European colonists to be unsuitable for wine. In the 19th century, Ephraim Bull of Concord, Massachusetts, cultivated seeds from wild Vitis labrusca vines to create the Concord grape which would become an important agricultural crop in the United States.[8]

Description

Grapes are a type of fruit that grow in clusters of 15 to 300, and can be crimson, black, dark blue, yellow, green, orange, and pink. "White" grapes are actually green in color, and are evolutionarily derived from the purple grape. Mutations in two regulatory genes of white grapes turn off production of anthocyanins, which are responsible for the color of purple grapes.[9] Anthocyanins and other pigment chemicals of the larger family of polyphenols in purple grapes are responsible for the varying shades of purple in red wines.[10][11] Grapes are typically an ellipsoid shape resembling a prolate spheroid.

Nutrition

Raw grapes are 81% water, 18% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and have negligible fat (table). A 100-gram (3 1⁄2-ounce) reference amount of raw grapes supplies 288 kilojoules (69 kilocalories) of food energy and a moderate amount of vitamin K (14% of the Daily Value), with no other micronutrients in significant content.

Grapevines

Most grapes come from cultivars of Vitis vinifera, the European grapevine native to the Mediterranean and Central Asia. Minor amounts of fruit and wine come from American and Asian species such as:

- Vitis amurensis, the most important Asian species

- Vitis labrusca, the North American table and grape juice grapevines (including the Concord cultivar), sometimes used for wine, are native to the Eastern United States and Canada.

- Vitis mustangensis (the mustang grape), found in Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma

- Vitis riparia, a wild vine of North America, is sometimes used for winemaking and for jam. It is native to the entire Eastern United States and north to Quebec.

- Vitis rotundifolia (the muscadine), used for jams and wine, is native to the Southeastern United States from Delaware to the Gulf of Mexico.

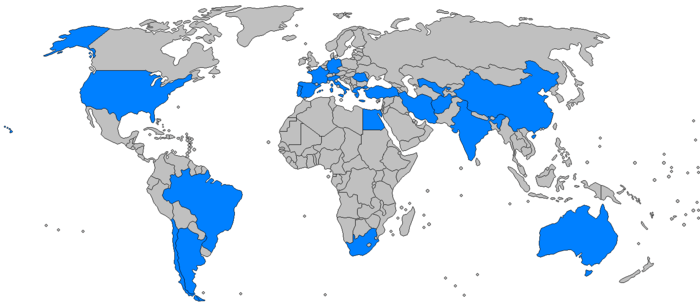

Distribution and production

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 75,866 square kilometers of the world are dedicated to grapes. Approximately 71% of world grape production is used for wine, 27% as fresh fruit, and 2% as dried fruit. A portion of grape production goes to producing grape juice to be reconstituted for fruits canned "with no added sugar" and "100% natural". The area dedicated to vineyards is increasing by about 2% per year.

There are no reliable statistics that break down grape production by variety. It is believed that the most widely planted variety is Sultana, also known as Thompson Seedless, with at least 3,600 km2 (880,000 acres) dedicated to it. The second most common variety is Airén. Other popular varieties include Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon blanc, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Grenache, Tempranillo, Riesling, and Chardonnay.[13]

| Country | Area (km²) |

|---|---|

| 11,750 | |

| 8,640 | |

| 8,270 | |

| 8,120 | |

| 4,150 | |

| 2,860 | |

| 2,480 | |

| 2,160 | |

| 2,080 | |

| 1,840 | |

| 1,642 | |

| 1,459 |

| Rank | Country | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,038,703 | 8,651,831 | 9,174,280 | 9,600,000 F | |

| 2 | 6,629,198 | 6,777,731 | 6,756,449 | 6,661,820 | |

| 3 | 8,242,500 | 7,787,800 | 7,115,500 | 5,819,010 | |

| 4 | 6,101,525 | 5,794,433 | 6,588,904 | 5,338,512 | |

| 5 | 5,535,333 | 6,107,617 | 5,809,315 | 5,238,300 | |

| 6 | 4,264,720 | 4,255,000 | 4,296,351 | 4,275,659 | |

| 7 | 2,600,000 | 2,903,000 | 3,149,380 | 3,200,000 F | |

| 8 | 2,181,567 | 2,616,613 | 2,750,000 | 2,800,000 F | |

| 9 | 2,305,000 | 2,225,000 | 2,240,000 | 2,150,000 F | |

| 10 | 1,748,590 | 1,743,496 | 1,683,927 | 1,839,030 | |

| — | World | 58,521,410 | 58,292,101 | 58,500,118 | 67,067,128 |

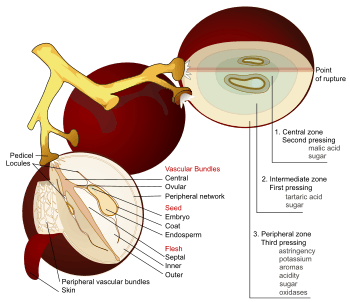

Table and wine grapes

Commercially cultivated grapes can usually be classified as either table or wine grapes, based on their intended method of consumption: eaten raw (table grapes) or used to make wine (wine grapes). While almost all of them belong to the same species, Vitis vinifera, table and wine grapes have significant differences, brought about through selective breeding. Table grape cultivars tend to have large, seedless fruit (see below) with relatively thin skin. Wine grapes are smaller, usually seeded, and have relatively thick skins (a desirable characteristic in winemaking, since much of the aroma in wine comes from the skin). Wine grapes also tend to be very sweet: they are harvested at the time when their juice is approximately 24% sugar by weight. By comparison, commercially produced "100% grape juice", made from table grapes, is usually around 15% sugar by weight.[15]

Seedless grapes

Seedless cultivars now make up the overwhelming majority of table grape plantings. Because grapevines are vegetatively propagated by cuttings, the lack of seeds does not present a problem for reproduction. It is an issue for breeders, who must either use a seeded variety as the female parent or rescue embryos early in development using tissue culture techniques.

There are several sources of the seedlessness trait, and essentially all commercial cultivators get it from one of three sources: Thompson Seedless, Russian Seedless, and Black Monukka, all being cultivars of Vitis vinifera. There are currently more than a dozen varieties of seedless grapes. Several, such as Einset Seedless, Benjamin Gunnels's Prime seedless grapes, Reliance, and Venus, have been specifically cultivated for hardiness and quality in the relatively cold climates of northeastern United States and southern Ontario.[16]

An offset to the improved eating quality of seedlessness is the loss of potential health benefits provided by the enriched phytochemical content of grape seeds (see Health claims, below).[17][18]

Raisins, currants and sultanas

In most of Europe and North America, dried grapes are referred to as "raisins" or the local equivalent. In the UK, three different varieties are recognized, forcing the EU to use the term "dried vine fruit" in official documents.

A raisin is any dried grape. While raisin is a French loanword, the word in French refers to the fresh fruit; grappe (from which the English grape is derived) refers to the bunch (as in une grappe de raisins).

A currant is a dried Zante Black Corinth grape, the name being a corruption of the French raisin de Corinthe (Corinth grape). Currant has also come to refer to the blackcurrant and redcurrant, two berries unrelated to grapes.

A sultana was originally a raisin made from Sultana grapes of Turkish origin (known as Thompson Seedless in the United States), but the word is now applied to raisins made from either white grapes or red grapes that are bleached to resemble the traditional sultana.

Juice

Grape juice is obtained from crushing and blending grapes into a liquid. The juice is often sold in stores or fermented and made into wine, brandy, or vinegar. Grape juice that has been pasteurized, removing any naturally occurring yeast, will not ferment if kept sterile, and thus contains no alcohol. In the wine industry, grape juice that contains 7–23% of pulp, skins, stems and seeds is often referred to as "must". In North America, the most common grape juice is purple and made from Concord grapes, while white grape juice is commonly made from Niagara grapes, both of which are varieties of native American grapes, a different species from European wine grapes. In California, Sultana (known there as Thompson Seedless) grapes are sometimes diverted from the raisin or table market to produce white juice.[19]

Pomace and phytochemicals

Winemaking from red and white grape flesh and skins produces substantial quantities of organic residues, collectively called pomace (also "marc"), which includes crushed skins, seeds, stems, and leaves generally used as compost.[20] Grape pomace – some 10-30% of the total mass of grapes crushed – contains various phytochemicals, such as unfermented sugars, alcohol, polyphenols, tannins, anthocyanins, and numerous other compounds, some of which are harvested and extracted for commercial applications (a process sometimes called "valorization" of the pomace).[20][21]

Skin

Anthocyanins tend to be the main polyphenolics in purple grapes, whereas flavan-3-ols (i.e. catechins) are the more abundant class of polyphenols in white varieties.[22] Total phenolic content is higher in purple varieties due almost entirely to anthocyanin density in purple grape skin compared to absence of anthocyanins in white grape skin.[22] Phenolic content of grape skin varies with cultivar, soil composition, climate, geographic origin, and cultivation practices or exposure to diseases, such as fungal infections.

Muscadine grapes contain a relatively high phenolic content among dark grapes.[23][24] In muscadine skins, ellagic acid, myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, and trans-resveratrol are major phenolics.[25]

The flavonols syringetin, syringetin 3-O-galactoside, laricitrin and laricitrin 3-O-galactoside are also found in purple grape but absent in white grape.[26]

Seeds

Muscadine grape seeds contain about twice the total polyphenol content of skins.[24] Grape seed oil from crushed seeds is used in cosmeceuticals and skincare products. Grape seed oil, including tocopherols (vitamin E) and high contents of phytosterols and polyunsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid, oleic acid, and alpha-linolenic acid.[27][28][29]

Resveratrol

Resveratrol, a stilbene compound, is found in widely varying amounts among grape varieties, primarily in their skins and seeds.[30] Muscadine grapes have about one hundred times higher concentration of stilbenes than pulp. Fresh grape skin contains about 50 to 100 micrograms of resveratrol per gram.[31]

Health claims

French paradox

Comparing diets among Western countries, researchers have discovered that although French people tend to eat higher levels of animal fat, the incidence of heart disease remains low in France. This phenomenon has been termed the French paradox, and is thought to occur from protective benefits of regularly consuming red wine, among other dietary practices. Alcohol consumption in moderation may be cardioprotective by its minor anticoagulant effect and vasodilation.[32]

Although adoption of wine consumption is generally not recommended by health authorities,[33] some research indicates moderate consumption, such as one glass of red wine a day for women and two for men, may confer health benefits.[34][35][36] Alcohol itself may have protective effects on the cardiovascular system.[37]

Use in religion

Christians have traditionally used wine during worship services as a means of remembering the blood of Jesus Christ which was shed for the remission of sins. Christians who oppose the partaking of alcoholic beverages sometimes use grape juice or water as the "cup" or "wine" in the Lord's Supper.[39]

The Catholic Church continues to use wine in the celebration of the Eucharist because it is part of the tradition passed down through the ages starting with Jesus Christ at the Last Supper, where Catholics believe the consecrated bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Jesus Christ, a dogma known as transubstantiation.[40] Wine is used (not grape juice) both due to its strong Scriptural roots, and also to follow the tradition set by the early Christian Church.[41] The Code of Canon Law of the Catholic Church (1983), Canon 924 says that the wine used must be natural, made from grapes of the vine, and not corrupt.[42] In some circumstances, a priest may obtain special permission to use grape juice for the consecration; however, this is extremely rare and typically requires sufficient impetus to warrant such a dispensation, such as personal health of the priest.

Although alcohol is permitted in Judaism, grape juice is sometimes used as an alternative for kiddush on Shabbat and Jewish holidays, and has the same blessing as wine. Many authorities maintain that grape juice must be capable of turning into wine naturally in order to be used for kiddush. Common practice, however, is to use any kosher grape juice for kiddush.

Gallery

- Flower buds

- Flowers

- Immature fruit

- Grapes in Iran

Wine grapes

Wine grapes Vineyard in the Troodos Mountains

Vineyard in the Troodos Mountains seedless grapes

seedless grapes Grapes in the La Union, Philippines

Grapes in the La Union, Philippines

See also

- Annual growth cycle of grapevines

- Drakshasava, a traditional Ayurvedic tonic made from grapes

- Grape syrup

- List of grape dishes

- List of grape varieties

- Propagation of grapevines

- The Fox and the Grapes

Sources

- This, Patrice; Lacombe, Thierry; Thomash, Mark R. (2006). "Historical Origins and Genetic Diversity of Wine Grapes" (PDF). Trends in Genetics. 22 (9): 511–519. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.07.008. PMID 16872714. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-04.

- McGovern, Patrick E. (2003). Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (PDF). Princeton University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-04.

- McGovern, P. E. "Georgia: Homeland of Winemaking and Viticulture". Archived from the original on 2013-05-30.

- Keys, David (2003-12-28) Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. archaeology.ws.

- Owen, James (12 January 2011). "Earliest Known Winery Found in Armenian Cave". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2017-06-03. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Hugh Johnson, "The Story of Wine", New Illustrated Edition, p. 58 & p. 131, Mitchell Beazley 2004, ISBN 1-84000-972-1

- "Grape". Better Health Channel Victoria. October 2015. Archived from the original on 2018-01-09. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Jancis Robinson, Vines, Grapes & Wines (Mitchell Beazley, 1986, ISBN 1-85732-999-6), pp 8, 18, 228.

- Walker, A. R.; Lee, E.; Bogs, J.; McDavid, D. A. J.; Thomas, M. R.; Robinson, S. P. (2007). "White grapes arose through the mutation of two similar and adjacent regulatory genes". The Plant Journal. 49 (5): 772–785. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02997.x. PMID 17316172.

- Waterhouse, A. L. (2002). "Wine phenolics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 957 (1): 21–36. Bibcode:2002NYASA.957...21W. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02903.x. PMID 12074959.

- Brouillard, R.; Chassaing, S.; Fougerousse, A. (2003). "Why are grape/fresh wine anthocyanins so simple and why is it that red wine color lasts so long?". Phytochemistry. 64 (7): 1179–1186. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00518-1. PMID 14599515.

- Top 20 grape producing countries in 2012 Archived 2011-07-13 at the Wayback Machine faostat.fao.org

- "The most widely planted grape in the world". freshplaza.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- "Production of Grape by countries". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- "WineLoversPage – Straight talk in plain English about fine wine". WineLoversPage. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- Reisch BI, Peterson DV, Martens M-H. "Seedless Grapes" Archived 2008-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, in "Table Grape Varieties for Cool Climates", Information Bulletin 234, Cornell University, New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, retrieved December 30, 2008

- Shi, J.; Yu, J.; Pohorly, J. E.; Kakuda, Y. (2003). "Polyphenolics in Grape Seeds—Biochemistry and Functionality". Journal of Medicinal Food. 6 (4): 291–299. doi:10.1089/109662003772519831. PMID 14977436.

- Parry, J.; Su, L.; Moore, J.; Cheng, Z.; Luther, M.; Rao, J. N.; Wang, J. Y.; Yu, L. L. (2006). "Chemical Compositions, Antioxidant Capacities, and Antiproliferative Activities of Selected Fruit Seed Flours". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (11): 3773–3778. doi:10.1021/jf060325k. PMID 16719495.

- "Thompson Seedless Grape Juice". sweetwatercellars.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- Gómez-Brandón, María; Lores, Marta; Insam, Heribert; Domínguez, Jorge (2019-04-02). "Strategies for recycling and valorization of grape marc". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 39 (4): 437–450. doi:10.1080/07388551.2018.1555514. ISSN 0738-8551. PMID 30939940.

- Muhlack, Richard A.; Potumarthi, Ravichandra; Jeffery, David W. (2018). "Sustainable wineries through waste valorisation: A review of grape marc utilisation for value-added products". Waste Management. 72: 99–118. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2017.11.011. ISSN 0956-053X. PMID 29132780.

- Cantos, E.; Espín, J. C.; Tomás-Barberán, F. A. (2002). "Varietal differences among the polyphenol profiles of seven table grape cultivars studied by LC-DAD-MS-MS". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 50 (20): 5691–5696. doi:10.1021/jf0204102. PMID 12236700.

- Ector BJ, Magee JB, Hegwood CP, Coign MJ (1996). "Resveratrol Concentration in Muscadine Berries, Juice, Pomace, Purees, Seeds, and Wines". Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 47 (1): 57–62. Archived from the original on 2006-11-19.

- Xu, Changmou; Yagiz, Yavuz; Zhao, Lu; Simonne, Amarat; Lu, Jiang; Marshall, Maurice R. (2017). "Fruit quality, nutraceutical and antimicrobial properties of 58 muscadine grape varieties (Vitis rotundifolia Michx.) grown in United States". Food Chemistry. 215: 149–156. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.163. ISSN 0308-8146. PMID 27542461.

- Pastrana-Bonilla, E.; Akoh, C. C.; Sellappan, S.; Krewer, G. (2003). "Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of muscadine grapes". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (18): 5497–5503. doi:10.1021/jf030113c. PMID 12926904.

- Mattivi, F.; Guzzon, R.; Vrhovsek, U.; Stefanini, M.; Velasco, R. (2006). "Metabolite Profiling of Grape: Flavonols and Anthocyanins". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (20): 7692–7702. doi:10.1021/jf061538c. PMID 17002441.

- Beveridge, T. H. J.; Girard, B.; Kopp, T.; Drover, J. C. G. (2005). "Yield and Composition of Grape Seed Oils Extracted by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Petroleum Ether: Varietal Effects". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (5): 1799–1804. doi:10.1021/jf040295q. PMID 15740076.

- Crews, C.; Hough, P.; Godward, J.; Brereton, P.; Lees, M.; Guiet, S.; Winkelmann, W. (2006). "Quantitation of the Main Constituents of Some Authentic Grape-Seed Oils of Different Origin". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (17): 6261–6265. doi:10.1021/jf060338y. PMID 16910717.

- Tangolar, S. G. K.; Özoğul, Y. I.; Tangolar, >S.; Torun, A. (2009). "Evaluation of fatty acid profiles and mineral content of grape seed oil of some grape genotypes". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 60 (1): 32–39. doi:10.1080/09637480701581551. PMID 17886077.

- "Resveratrol". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Li, X.; Wu, B.; Wang, L.; Li, S. (2006). "Extractable Amounts of trans-Resveratrol in Seed and Berry Skin in Vitis Evaluated at the Germplasm Level". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (23): 8804–8811. doi:10.1021/jf061722y. PMID 17090126.

- Providência, R. (2006). "Cardiovascular protection from alcoholic drinks: Scientific basis of the French Paradox". Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia. 25 (11): 1043–1058. PMID 17274460.

- Alcohol, wine and cardiovascular disease. American Heart Association

- Alcohol. Harvard School of Public Health

- Mukamal, K. J.; Kennedy, M.; Cushman, M.; Kuller, L. H.; Newman, A. B.; Polak, J.; Criqui, M. H.; Siscovick, D. S. (2007). "Alcohol Consumption and Lower Extremity Arterial Disease among Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study". American Journal of Epidemiology. 167 (1): 34–41. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm274. PMID 17971339.

- De Lange, D. W.; Van De Wiel, A. (2004). "Drink to Prevent: Review on the Cardioprotective Mechanisms of Alcohol and Red Wine Polyphenols". Seminars in Vascular Medicine. 4 (2): 173–186. doi:10.1055/s-2004-835376. PMID 15478039.

- Sato, M.; Maulik, N.; Das, D. K. (2002). "Cardioprotection with alcohol: Role of both alcohol and polyphenolic antioxidants". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 957: 122–135. Bibcode:2002NYASA.957..122S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02911.x. PMID 12074967.

- Raisins/Grapes Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. The Merck Veterinary Manual

- "Why do most Methodist churches serve grape juice instead of wine for Holy Communion?". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1413". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- "The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist". Newadvent.org. 1909-05-01. Archived from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- "Altar wine, Catholic encyclopedia". Newadvent.org. 1907-03-01. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

Further reading

- Creasy, G. L. and L. L. Creasy (2009). Grapes (Crop Production Science in Horticulture). CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-401-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Grapes |