Flag of Italy

The flag of Italy (Italian: Bandiera d'Italia, Italian: [banˈdjɛːra diˈtaːlja]), often referred to in Italian as il Tricolore (Italian: [il trikoˈloːre]); is a tricolour featuring three equally sized vertical pales of green, white and red, with the green at the hoist side. Its current form has been in use since 18 June 1946 and was formally adopted on 1 January 1948.[1]

| |

| Name | Tricolore |

|---|---|

| Use | National flag |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 18 June 1946 |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of green, white and red |

Variant flag of Italy | |

| Use | Civil ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 9 November 1948 |

| Design | A defaced Italian tricolour with the naval coat of arms without the golden castle on the top. |

Variant flag of Italy | |

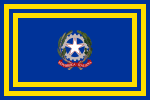

| Use | State ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 24 October 2003 |

| Design | Italian tricolour defaced with the Emblem of Italy. |

Variant flag of Italy | |

| Use | Naval ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 9 November 1947 |

| Design | A defaced Italian tricolour with the naval coat of arms. |

Variant flag of Italy | |

| Use | War flag |

| Proportion | 1:1 |

| Design | The Italian tricolor with a different aspect ratio |

The Tricolour Day, Flag Day dedicated to the Italian flag, is established by law n. 671 of 31 December 1996, which is held every year on 7 January. This celebration commemorates the first official adoption of the tricolour as a national flag by the Cispadane Republic, a Napoleonic sister republic of Revolutionary France, which took place in Reggio Emilia on 7 January 1797. The Italian national colours appeared for the first time in Genoa on a tricolour cockade on 21 August 1789, anticipating by seven years the first green, white and red Italian military war flag, which was adopted by the Lombard Legion on 11 October 1796.

The Cispadane Republic supplanted the Duchy of Milan after Napoleon's victorious army crossed Italy in 1796. The colours chosen by the Cispadane Republic were red and white, which were the colours of the flag of recently conquered Milan, and green, which was the colour of the uniform of the Milanese civic guard. During this time, many small French-proxy republics of Jacobin inspiration supplanted the ancient absolute Italian states and almost all, with variants of colour, used flags characterised by three bands of equal size, clearly inspired by the French model of 1790.[2]

After the date of 7 January 1797 the popular consideration for the Italian flag grew steadily, until it became one of the most important symbols of the Risorgimento, which culminated on 17 March 1861 with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, of which the tricolour rose to national flag. Since its adoption, the tricolour has become one of most recognizable and defining features of united Italian statehood in the following two centuries of history of Italy.

Italian patriots later identified the three colours with the Mediterranean maquis (Green), the snow-capped Alps (White), and the blood spilt during the Risorgimento (Red). A philosophic and Catholic interpretation associates the tricolour with the theological virtues: Hope (Green), Faith (White), and Love (Red).

History

The birth of Italian national colours on a cockade

The Italian tricolor, like other tricolour flags, is inspired by the French one, introduced by the revolution in the autumn of 1790 on French Navy warships[3] and symbol of the renewal perpetrated by the origins of Jacobinism.[4][5][6] Shortly after the French revolutionary events, even in Italy the ideals of social innovation began to spread widely – on the basis of the advocacy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 – and subsequently also political, with the first patriotic ferments addressed to the national self-determination: for this reason the French blue, white and red flag became the first reference of the Italian Jacobins and subsequently a source of inspiration for the creation of an Italian identity flag.[6]

The first documented trace of the use of Italian national colours is dated 21 August 1789: in the historical archives of the Republic of Genoa it is reported that eyewitnesses had seen some demonstrators pinned on their clothes hanging a red, white and green cockade on their clothes.[7] The Italian gazettes of the time had in fact created confusion about the French facts, especially on the replacement of green with blue, reporting the news that the French tricolour was green, white and red.[8] The green was then maintained by the Italian Jacobins because it represented nature and therefore – metaphorically – also natural rights, or social equality and freedom.[9]

The Italian cockade then reappeared several years later on 13–14 November 1794 worn by a group of students of the University of Bologna, led by Luigi Zamboni and Giovanni Battista De Rolandis, who attempted to plot a popular riot to topple the Catholic government of Bologna,[10][11] a city which was part of the Papal States at the time. The law students defined themselves as "patriots" and wore tricolour cockades to signal they were inspired by Jacobin revolutionary ideals, but modified them also to distinguish themselves from the French cockade. The chosen colours were white and red since those are the colours of the flag of Bologna, some scholars contend green was added only for the event to give it a more ideological effect; not all agree that the cockades used by the Bologna plotters actually had three colours, since a myth about that may have been created a year later.[12]

The birth of the flag of Italy

The oldest documented trace that mentions the Italian tricolour flag is linked to Napoleon Bonaparte's first descent into the Italian peninsula. The first territory to be conquered by Napoleon was Piedmont; in the historical archive of the Piedmontese municipality of Cherasco is preserved a document attesting, on 13 May 1796, on the occasion of the Armistice of Cherasco between Napoleon and the Austro-Piedmontese troops, the first mention of the Italian tricolor, referring to municipal banners hoisted on three towers in the historic center.[13] On the document the term «green» was subsequently crossed and replaced by «bleu», that is, by the colour that forms - together with white and red - the French flag.[4] It is on the French flag that the documents, at least until the entrance of the Italian Napoleonic army in Milan in October 1796, refer when they use the term "tricolor".[14]

On 11 October 1796 Napoleon communicated to the Directorate the birth of the Lombard Legion, a military unit constituted by the General Administration of Lombardy,[15][16] a government that was headed by the Transpadane Republic.[17] On this document, with reference to its war flag, which followed the French tricolour and which was proposed to Napoleon by the Milanese patriots,[18] it is reported that this military unit would have had a red, white and green banner (red and white in honor of the flag of Milan, and green from the uniform of the civic guard of Milan).[19][20][21] In a solemn ceremony at the Piazza del Duomo on 16 November 1796, a military flag was presented to the Lombard Legion. The Lombard Legion was therefore the first Italian military department to equip itself, as a banner, with a tricolour flag.[17]

On 19 June 1796, Bologna was occupied by Napoleon's troops.[22] On 18 October 1796,[23] together with the establishment of the Italian Legion (the military banner of this military unit was composed of a red, white and green tricolor, probably inspired by the similar decision of the Lombard Legion[18][19][24]), the wire Napoleonic congregation of magistrates and deputy deputies of Bologna, at the third point of the discussion, decided to create a civic banner red, white and green, this time released from military use.[23] Following the adoption by the Bolognese congregation, the Italian flag became a political symbol of the struggle for the independence of Italy from foreign powers, supported by its use also in the civil sphere.[23] The following adoption of the Italian flag by a state body, the Cispadan Republic, was inspired by this Bolognese banner, linked to a municipal reality and therefore still having a purely local scope, and to the previous military banners of the Lombard Legion and Italian Legion, which took place on 7 January 1797.[5][25]

The first red, white and green national flag of a sovereign Italian state was instead adopted, as mentioned, on 7 January 1797, when the Fourteenth Parliament of the Cispadane Republic, on the proposal of deputy Giuseppe Compagnoni of Lugo, decreed "to make universal the ... standard or flag of three colours, green, white, and red ...":[26]

[...] From the minutes of the XIV Session of the Cispadan Congress: Reggio Emilia, 7 January 1797, 11 am. Patriotic Hall. The participants are 100, deputies of the populations of Bologna, Ferrara, Modena and Reggio Emilia. Giuseppe Compagnoni also motioned that the standard or Cispadan Flag of three colours, Green, White and Red, should be rendered Universal and that these three colours should also be used in the Cispadan Cockade, which should be worn by everyone. It is decreed. [...][27]

— Decree of adoption of the tricolour flag by the Cispadane Republic

This was probably because the Lombard Legion had carried banners of red, white and green, and the same colours were later adopted in the banners of the Italian Legion, which was formed by soldiers coming from Emilia and Romagna. The flag was a horizontal square with red uppermost and, at the heart of the white fess, an emblem composed of a garland of laurel decorated with a trophy of arms and four arrows, representing the four provinces that formed the Republic.

The Cispadane Republic and the Transpadane Republic, which had itself been using a vertical Italian tricolour from 1796, merged into the Cisalpine Republic and adopted the vertical square tricolour without badge in 1798. The flag was maintained until 1802, when it was renamed the Napoleonic Italian Republic, and a new flag was adopted, this time with a red field carrying a green square within a white lozenge.

It was in this period that the green, white and red tricolour predominantly penetrated the collective imagination of the Italians, becoming, to all intents and purposes, an unequivocal symbol of Italianness.[28][29] In less than twenty years, the flag red, white and green, from a simple flag derived from the French one, had acquired its own peculiarity, becoming very famous and known.[28]

In 1799, the independent Republic of Lucca came under French influence and adopted as its flag a horizontal tricolour with green uppermost; this lasted until 1801. In 1805 Napoleon installed his sister, Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, as Princess of Lucca and Piombino. This affair is commemorated in the opening of Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace.[30]

In the same year, after Napoleon had crowned himself first French Emperor, the Italian Republic was transformed into the first Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, or Italico, under his direct rule. The flag of the Kingdom of Italy was that of the Republic in rectangular form, charged with the golden Napoleonic eagle. This remained in use until the abdication of Napoleon in 1814.

Risorgimento and Italian unification

_crowned.svg.png) | |

| Use | State flag, state and naval ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 1861 (Sardinia 1851) |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of green, white, and red, defaced with the arms of Savoy and crown |

.svg.png) Variant flag of the Kingdom of Italy | |

| Use | Civil flag and ensign |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 1861 (Sardinia 1851) |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of green, white, and red, defaced with the arms of Savoy |

.svg.png) Variant flag of the Kingdom of Italy | |

| Use | War flag |

| Proportion | 1:1 |

| Adopted | 1861 (Sardinia 1848)[31] |

| Design | A defaced Italian tricolour |

Between 1820 and 1861, a sequence of events led to the independence and unification of Italy (except for Venetia, Rome, Trento and Trieste, known as Italia irredenta, which were united with the rest of Italy in 1866, 1870, and 1918 respectively); this period of Italian history is known as the Risorgimento, or resurgence. During this period, the tricolore became the symbol which united all the efforts of the Italian people towards freedom and independence.[32] The tricolour waved for the first time in the history of the Risorgimento in the Cittadella of Alessandria during the revolutions of 1820 to then reappear during revolutions of 1830.

The Italian tricolour, defaced with the Savoyan coat of arms, was first adopted as a war flag by the Kingdom of Sardinia–Piedmont army in 1848. In his Proclamation to the Lombard–Venetian people, Charles Albert said "... in order to show more clearly with exterior signs the commitment to Italian unification, We want that Our troops ... have the Savoy shield placed on the Italian tricolour flag."[33] As the arms, blazoned gules a cross argent, mixed with the white of the flag, it was fimbriated azure, blue being the dynastic colour, although this does not conform to the heraldic rule of tincture.[34] The rectangular civil and state variants were adopted in 1851.

In the same year, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany became constitutional and dropped the Austrian flag, with Austria–Lorraine great coat of arms, in favour of the defaced Italian tricolour with simplified arms. It is worthy of note, however, that the arms bear the red-white-red flag of Austria, the opponent of Italian unification. In 1859, the Granducato officially ceased to exist, being joined to the Duchies of Modena and Parma to form the United Provinces of Central Italy, which used the undefaced tricolour until it was annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia the following year.

The flag of the Constitutional Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, a white field charged with the coats of arms of Castile, Leon, Aragon, Two Sicilies, and Granada, was modified by Ferdinand II through the addition of a red and green border. This flag lasted from 3 April 1848 until 19 May 1849. The Provisional Government of Sicily, which lasted from 12 January 1848 to 15 May 1849, adopted the Italian tricolour, defaced with the trinacria, or triskelion.

In the same year, the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia revolted against the Austrian Empire in the Five Days of Milan, forming the Provisional Government of Lombardy on 22 March 1848 and Provisional Government of Venice, the so-called "Republic of San Marco", a day later. The flags that they adopted, marked the link to Italian independence and unification efforts; the former, the Italian tricolour undefaced, and the latter, charged with the winged lion of St. Mark, from the flag of the Most Serene Republic, on a white canton.[35] These lasted until 6 and 24 August 1849 respectively.

In 1849, the new Roman Republic adopted an Italian tricolour, sent from Venice, bearing the legend DIO E POPOLO in red capital letters. This lasted for four months, while the Papal States of the Church was in abeyance.[36]

This spread throughout the Italian peninsula was the demonstration that the tricolour flag had by now assumed a consolidated symbolism valid throughout the national territory.[37] The great enthusiasm of the population towards the tricolour is precisely from these years: in addition to the army of the Kingdom of Sardinia and the troops of volunteers who participated in the second war of independence,[37] the green, white and red flag spread widely available in newly conquered or annexed regions by plebiscite, appearing on house windows, in shop windows and in public places such as hotels, taverns, taverns, etc.[38]

In 1860, the flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was again modified to the defaced Italian tricolour with the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies coat of arms.[39] Adopted on 21 June 1860, this lasted until 17 March 1861, when the Two Sicilies was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy, after its defeat in the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi.

On 15 April 1861, the flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia was declared the flag of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy.[40] This Italian tricolour, with the armorial bearings of the former Royal House of Savoy was the first national flag and lasted in that form for 85 years until the birth of the Italian Republic in 1946.

.jpg)

The tricolore, in this context, had a universal, transversal meaning, shared by both monarchists and republicans, progressives and conservatives and Guelphs as well as by the Ghibellines: it was chosen as the flag of a united Italy also for this reason.[41] After the Unification of Italy the use of the tricolour became increasingly widespread among the population:[42] the flag, and its colours, began to appear on the labels of commercial products, on school notebooks, on the first cars, on the cigar packs, etc.[42] Even among the aristocrats it was successful: the most important families often had a flag bearer installed on the main façade of their mansions where they placed the Italian tricolor.[42] He then began to appear outside public buildings, schools, judicial offices and post offices .[42] The introduction of the tricolour band for mayors and for the jurors of the assize courts is of this period.[42]

Between the two world wars

With the March on Rome (1922) and the establishment of the fascist dictatorship the Italian flag lost its symbolic uniqueness partly obscured by the iconography of the regime.[43][44] When it was used, as inside the symbol of the National Fascist Party, its history was distorted, given that the tricolour was born as a symbol of freedom and civil rights.[45] Despite this supporting role, with the royal decree nº 2072 of 24 September 1923 and subsequently with the law nº2264 of 24 December 1925, the tricolour officially became the national flag of the Kingdom of Italy.[46][47]

In 1926, the Fascist government attempted to have the Italian national flag redesigned by having the fasces, the symbol used by the Fascist movement, included in the flag.[48] However, this attempt by the Fascist government to change the Italian flag to incorporate the fasces was stopped by strong opposition to the proposal by Italian monarchists.[48] Afterwards, the Fascist government raised the national tricolour flag along with a Fascist black flag in public ceremonies.[49][50]

Italian Social Republic

| |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 1943 |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of green, white, and red. |

Variant flag of the Italian Social Republic | |

| Use | War flag |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 1944[51] |

| Design | A defaced Italian tricolour |

The Italian flag came back strongly after the Armistice of Cassibile of 8 September 1943, where it was taken as a symbol by the two sides who faced each other in the Italian Civil War[47][52] in an attempt to recall the Risorgimento and its cultural tradition.[53] In particular, it was used by the partisans as a symbol of the struggle against tyrants and emblem of the dream of a free Italy:[52] even the communist partisan brigades, which had the red flag as the official banner, often waved the Italian flag.[52]

Tricolour flags were also the official banners of the Italian Partisan Republics and of the National Liberation Committee, as well as their antagonists, the Republicans.[54] The national flag of the short-lived Fascist state in northern Italy, the Italian Social Republic (1943–1945), or "Republic of Salò" as it was commonly known, was identical to the flag of the modern Italian Republic, as both republics used the previous flag of the Kingdom of Italy with the coat of arms of Savoy removed.

This flag was somewhat rarely seen, however, while the war flag, charged with a silver/black eagle clutching horizontally placed fascio littorio (literally, bundles of the lictors), was very common in propaganda.[51] Italian fascism derived its name from the fasces, which symbolised imperium, or power and authority, in ancient Rome. Roman legions had carried the aquila, or eagle, as signa militaria.

On 25 April 1945, known as festa della liberazione, the government of Benito Mussolini fell. The Italian Social Republic had existed for slightly more than one year and a half.

Italian Republic

_(5799312802).jpg)

With the birth of the Italian Republic (1946), thanks to the decree of the President of the Council of Ministers No. 1 of 19 June 1946, the Italian flag was modified; compared to the monarchic banner, the Savoy coat of arms was eliminated.[55][56][57] This decision was later confirmed in the session of 24 March 1947 by the Constituent Assembly, which decreed the insertion of article 12 of the Italian Constitution, subsequently ratified by the Italian Parliament, which states :[56][58][59]

[...] The flag of the Republic is the Italian tricolour: green, white, and red, in three vertical bands of equal dimensions. [...][1]

— Article 12 of Constitution of Italy

The Republican tricolour was then officially and solemnly delivered to the Italian military corps on 4 November 1947 on the occasion of National Unity and Armed Forces Day.[60] The universally adopted ratio is 2:3, while the war flag is squared (1:1). Each comune also has a gonfalone bearing its coat of arms.

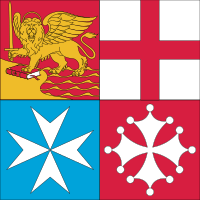

The Italian naval ensign comprises the national flag defaced with the arms of the Marina Militare; the Marina Mercantile (and private citizens at sea) use the civil ensign, differenced by the absence of the mural crown and the lion holding open the gospel, bearing the inscription PAX TIBI MARCE EVANGELISTA MEVS, instead of a sword.[61] The shield is quartered, symbolic of the four great thalassocracies of Italy, the repubbliche marinare of Venice (represented by the lion passant, top left), Genoa (top right), Amalfi (bottom left), and Pisa (represented by their respective crosses); the rostrata crown was proposed by Admiral Cavagnari in 1939 to acknowledge the Navy's origins in ancient Rome.[62]

In 1997, on its bicentenary, 7 January was declared Tricolour Day; it is intended as a celebration, though not a public holiday.[63] On 31 December 1996, with the same law that established the Tricolour Day, a celebration held on 7 January of each year in memory of the adoption of the red, white and green flag by the Cispadane Republic (7 January 1797), came established a national committee of twenty members that would have had the objective of organizing the first solemn commemoration of the birth of the Italian flag, which the following year would have made two hundred years.[64]

Among the events celebrating the bicentenary of the Italian flag, there was the realization of the longest tricolour in history, which also entered the Guinness World Records.[65] Work of the National Association returning from imprisonment, internment and liberation war, it was 1,570 m long, 4,8 m wide and had an area of 7,536 m²: it paraded in Rome, from the Colosseum to the Capitoline Hill.[65]

In 2003, a state ensign was created specifically for non-military vessels engaged in non-commercial government service; this defaces the Italian tricolour with the national coat of arms.[66] Since 1914, the Italian Air Force have also used a roundel of concentric rings in the colours of the tricolour as aircraft marking; substituted, from 1923 to 1943, by encircled fasces. The Frecce Tricolori, officially known as the 313º Gruppo Addestramento Acrobatico, is its aerobatic demonstration team.

The law n. 222 of 23 November 2012, concerning "Rules on the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the field of" Citizenship and Constitution and on the teaching of the Mameli hymn in schools", prescribes the study in schools of the Italian flag and others National symbols of Italy.[67]

Historical evolution of the Flag of Italy

Flag of the Cispadane Republic (1797)

Flag of the Cispadane Republic (1797) Flag of the Cisalpine Republic (1798–1802)

Flag of the Cisalpine Republic (1798–1802).svg.png) Flag of the Italian Republic (1802–1805)

Flag of the Italian Republic (1802–1805) Flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1805–1814)

Flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1805–1814) Flag of the Italian United Provinces (1831)

Flag of the Italian United Provinces (1831).svg.png) Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1848–1849)

Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1848–1849) Flag of the Republic of San Marco (1848–1849)

Flag of the Republic of San Marco (1848–1849).svg.png) Flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1851)

Flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1851)- Flag of the Kingdom of Sicily (1848–1849)

.svg.png) Flag of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (1848–1849)

Flag of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (1848–1849).svg.png) Flag of the Roman Republic (1849)

Flag of the Roman Republic (1849).svg.png) Flag of the Free cities of Menton and Roquebrune (1848–1849)

Flag of the Free cities of Menton and Roquebrune (1848–1849)_crowned.svg.png) Flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1851–1861)

Flag of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1851–1861)_crowned.svg.png) Flag of the United Provinces of Central Italy (1859–1860)

Flag of the United Provinces of Central Italy (1859–1860).svg.png) Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1860–1861)

Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1860–1861)_crowned.svg.png) Flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

Flag of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) Flag of the Italian Social Republic (1943–1945)

Flag of the Italian Social Republic (1943–1945)

War flag of the Italian Social Republic (6 May 1944 to 7 May 1945)[51]

War flag of the Italian Social Republic (6 May 1944 to 7 May 1945)[51] Flag of the National Liberation Committee (1943–1945)

Flag of the National Liberation Committee (1943–1945) Flag of the Trust Territory of Somaliland (1950–1960)

Flag of the Trust Territory of Somaliland (1950–1960)

Description

Colours

As already mentioned, the colours of the Italian flag are indicated in article 12[69] of the Constitution of Italy, published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 298, extraordinary edition, of 27 December 1947 and entered into force on 1 January 1948:

If the flag is exposed horizontally, the green part should be placed near the auction, with the white one in a central position and the red one outside, while if the banner is exposed vertically the green section should be placed above.[70]

Chromatic definition

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

The need to precisely define the colours was born from an event that happened at the Justus Lipsius building, seat of the Council of the European Union, of the European Council and of their Secretariat, when an Italian MEP, in 2002, noticed that the colours of the Italian flag were unrecognizable with red, for example, which had a shade that turned towards orange: for this reason the government, following the report of this MEP, decided to specifically define the colours of the Italian national flag.[71]

The shades of green, white and red were first specified by these official documents:[71][72]

- circulaire of the Undersecretary of State for the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of 18 September 2002;

- circulaire by the State Secretary for the Presidency of the Council of Ministers of 17 January 2003;

New documents then replaced the previous ones:[72]

- circulaire of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers No. EU 3.3.1 / 14545/1 of 2 June 2004;

- decree of the President of the Council of Ministers of 14 April 2006, "General provisions relating to ceremonial and precedence among public offices"

The chromatic tones of the three colours mentioned above, on polyester stamina, are enshrined in paragraph 1 of article n. 31 "Colour definition of the colours of the flag of the Republic", of Section V "Flag of Republic, National Anthem, National Feasts and State Funeral", of Chapter II "General provisions relating to ceremonial", of the annex "Presidency of the Council of Ministers - State Ceremonial Department", to the decree of the President of the Council of ministers of 14 April 2006 "General provisions on ceremonial and precedence between public offices", published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 174 of 28 July 2006.

Description Number RGB CMYK HSV Hex Fern Green 17-6153 TC (0, 140, 69) (100%, 0%, 51%, 45%) (150°, 100%, 55%) #008C45 Bright White 11-0601 TC (244, 245, 240) (0%, 0%, 2%, 4%) (72°, 2%, 96%) #F4F5F0 Flame Scarlet 18-1662 TC (205, 33, 42) (0%, 84%, 80%, 20%) (357°, 84%, 80%) #CD212A

Other official Italian flags

Standards of high institutional offices

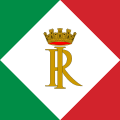

The President of the Italian Republic has an official standard. The current version is based on the square flag of the Napoleonic Italian Republic, on a field of blue, charged with the emblem of Italy in gold.[73][74][75] The square shape with a Savoy blue border symbolize the four Italian armed forces, namely the Italian Air Force, the Carabinieri, the Italian Army and the Italian Navy, of which the President is the commander.[76]

The first version of the standard, adopted in 1965 and used until 1990 was very similar to the current version only without the red, white and green. The emblem was also much larger.[77] This version of the standard was replaced in 1990 by then President Francesco Cossiga. Cossiga's new version of the standard contained the same Royal Blue background but now with a squared Italian national flag in the centre and no emblem.[78] This version was short lived however as only two years later it was replaced by the 1965 standard, only with a smaller emblem.[79] This version lasted until 2000 from where it was replaced by the current version.

After the Republic was proclaimed, the national flag was provisionally adopted as distinguishing flag of the head of state in place of the royal standard.[80] On the initiative of the Ministry of Defence, a project was prepared in 1965 to adopt a distinct flag.[81] Opportunity suggested the most natural solution was the Italian tricolour defaced with the coat of arms; however, under conditions of poor visibility, this could easily be mistaken for the standard of the President of the United States of Mexico, which is also that country's national flag. The standard is kept in the custody of the Commander of the Reggimento Corazzieri of the Arma dei Carabinieri, along with the war flag (assigned to Regiment in 1878).[82]

The Italian Constitution does not make provision for a Vice-President. However, separate insignia for the President of the Senate, in exercise of duties as acting head of state under Article 86, was created in 1986.[83] This has a white square on the blue field, charged with the arms of the Republic in silver. Distinguishing insignia for former Presidents of the Republic was created in 2001;[84] a tricolour in the style of the Presidential standard, it is emblazoned with the Cypher of Honour of the President of the Republic.[85]

The standard of President of the Council of Ministers of Italy, introduced for the first time in 1927 by Benito Mussolini, in its first form a littorio beam appeared in the middle of the drape. The sign was abolished in 1943, while the current one was defined in 2008 by Silvio Berlusconi. It consists of a blue drapery bordered by two gold-colored borders in the center of which stands the emblem of the Republic. The banner should be exposed to every official engagement of the president and on the vehicles that carry it, however it is almost never used. The main colours are blue and gold, which have always been considered colours linked to the command.[86]

Standard of a substitute President of the Republic

Standard of a substitute President of the Republic Standard of a President Emeritus of the Republic

Standard of a President Emeritus of the Republic Standard of the President of the Council of Ministers of Italy

Standard of the President of the Council of Ministers of Italy

Naval insignia

The naval flags carry symbols in the center of the white band to distinguish themselves from the flag of Mexico:[87]

- the military flag bears the emblem of the Navy: a shield, surmounted by a turreted and rostrum crown, which brings together in four parts the arms of four maritime republics: Republic of Venice (where the Lion of Saint Mark carries the sword), Republic of Genoa, Republic of Pisa and Republic of Amalfi;

- he civil flag carries a coat of arms identical to that of the Navy, but without a crown and in which the lion of Saint Mark carries the book;

- the state flag carries the emblem of the Italian Republic.

.svg.png) Jack of the (former) Regia Marina[88]

Jack of the (former) Regia Marina[88] Civil naval flag

Civil naval flag State naval flag

State naval flag Military naval flag

Military naval flag Military bowsprit flag (recto)

Military bowsprit flag (recto)

Protocol

The law, implementing Article 12 of the Constitution and following of Italy's membership of the European Union, lays down the general provisions governing the use and display of the flag of the Italian Republic and the flag of the European Union (in its territory).[89]

There are no international conventions on flying the flag, but protocol adopted by a large number of countries have such similarities as to suggest lines of commonly accepted practice. In general two areas of exposure are identified: national and international events. In both cases it is generally followed practice that national flags displayed in a group should be of equal size and each hoisted on its own flagstaff, of equal height, or on separate ropes if fixed on yardarm. It is always treated with dignity and should never be allowed to touch the ground or water.[90] Vertical hoist is transformationally identical to horizontal hoist (i.e. the flag is rotated 90 degrees).

When displayed alongside other flags, the national flag takes the position of honour; it is raised first and lowered last. Other national flags should be arranged in alphabetical order. Where two (or more than three) flags appear together, the national flag should be placed to the right (left of the observer); in a display of three flags in line, the national flag occupies the central position. The European flag is also flown from government buildings on a daily basis. In the presence of a foreign visitor belonging to a member state, this takes precedence over the Italian flag. As a sign of mourning, flags flown externally shall be lowered to half-mast; two black ribbons may be attached to those otherwise displayed.[91] Traditionally, the flag may be decorated with a golden fringe surrounding the perimeter.

Flag-raising

The flag-raising of the tricolour takes place at the first light of dawn, with the flag which is made to slide quickly and resolutely up to the end of the flagpole.[92] In the military sphere it is announced by trumpet blasts and is performed on the notes of Il Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro, Italian national anthem since 1946.[92]

The flagship, which takes place in the evening, is instead slower and more solemn so as not to make it seem a rapid lowering.[92] The tricolour can be exposed also during the night only if the place where it is flying is conveniently illuminated.[93]

In the presence of other flags, as well as receiving the highest honor position, it must be hoisted first and lowered last.[71]

Meaning of colours

As the similarity suggests, the Italian tricolour derives from the flag of France, which was born during the French revolution from the union of white – the colour of the monarchy – with red and blue – the colours of Paris[94] and which became the symbol of social and political renewal perpetrated by the original Jacobinism.[4][5][6]

As already mentioned, green, in the first Italian tricolour cockades, symbolized natural rights, namely social equality and freedom.[9] After various events it came to 7 January 1797, the date of the adoption of the tricolour flag by the Cispadane Republic, the first Italian sovereign state to make use of it.[5] During the Napoleonic period, the three colours acquired a more idealistic meaning for the population: the green represents hope, the white represents faith and the red represents love.[95][96]

Other less probable conjectures that explain the adoption of the green hypothesize a tribute that Napoleon wanted to give to Corsica, where he was born, or to a possible reference to the verdant Italian landscape.[95] For the adoption of greenery there is also the so-called "Masonic hypothesis": even for Freemasonry, green was the colour of nature, a symbol of human rights, which are naturally inherent in the human being,[23] as much as of the florid Italian landscape; this interpretation, however, is opposed by those who maintain that Freemasonry, as a secret society, did not have such an influence at the time that inspired Italian national colours.[97]

Another hypothesis that attempts to explain the meaning of the three Italian national colours would, without historical bases, be that the green is linked to the colour of the meadows and the Mediterranean maquis, the white to that of the snows of the Alps and the red to the blood spilt in the Wars of Italian Independence and Unification.[98][99]

A more religious interpretation is that the green represents hope, the white represents faith, and the red represents charity (an interpretation of the tricolor noted even in 1320 in the Divine Comedy of Italy’s own Dante Alighieri); this references the three theological virtues.[100]

Tricolour Day

To commemorate the birth of the Italian flag on 31 December 1996, the Tricolour Day was established, which is known in Italian as the Festa del Tricolore.[64] It is celebrated every year on 7 January, with the official celebrations being organized in Reggio nell'Emilia, the city where the first official adoption of the tricolour was declared as a national flag by an Italian sovereign state, the Cispadane Republic, which took place on 7 January 1797.[5]

In Reggio nell'Emilia, the Festa del Tricolore is celebrated in Piazza Prampolini, in front of the town hall, in the presence of one of the highest offices of the Italian Republic (the President of the Italian Republic or the president of one of the chambers), who attends the 'flag-raising on the notes of Il Canto degli Italiani and which renders military honors a reproduction of the flag of the Cispadane Republic.[101]

In Rome, at the Quirinal Palace, the ceremonial foresees instead the change of the Guard of honour in solemn form with the deployment and the parade of the Corazzieri Regiment in gala uniform and the Fanfare of the Carabinieri Cavalry Regiment.[102] This solemn rite is carried out only on three other occasions, during the celebrations of the Unification of Italy (17 March), of the Festa della Repubblica (2 June) and of the National Unity and Armed Forces Day (4 November).[102]

The Flag of Italy in museums

There are many museums that host at least one historic Italian flag. Located throughout the Italian peninsula, they are mainly located in northern Italy.[103]

The most important exhibition space that hosts Italian tricolour flags is found in the architectural complex of the Altare della Patria in Rome.[104] Inside the "Central Museum of the Risorgimento at the Vittoriano", this is its name, there are about seven hundred historical flags belonging to the Italian Army, Italian Navy and Italian Air Force departments, as well as the tricolour flag with which it was wrapped in 1921 coffin of the Unknown Soldier on his journey to the Altar of the Patria.[105] The oldest tricolour preserved in the Central Museum of the Risorgimento dates back to 1860:[105] it is one of the original tricolours that flew on the Lombardo steamship which, together with Piedmont steamship, participated in the expedition of the Thousand.[106] The Vittoriano also houses the Flag Memorial (it. Sacrario delel Bandiere), the museum that collects and preserves disused Italian war flags.[107]

Of particular importance is the Museum of the tricolour of Reggio nell'Emilia, a city that saw the birth of the Italian flag in 1797. Founded in 2004, it is located within the town hall of the Emilian city, adjacent to the Sala del Tricolore: documents are kept and memorabilia whose dating is attributable to a period between the arrival of Napoleon Bonaparte in Reggio (1796) and 1897, the year of the first centenary of the Italian flag.[108]

At the National Museum of the Italian Risorgimento in Turin, the only one of Risorgimento that officially has the title of "national", it is possible to find a rich collection of tricolours, including some dating back to the revolutions of 1848.[109] Among the relics of the Royal Armory of Turin there is a flag of 1855, a relic in the Crimean War, in which the Russian Empire lost to an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain and Kingdom of Sardinia.[110]

National flags similar to the Flag of Italy

The Italian national flag belongs to the family of flags derived from the French tricolor,[111] with all the meanings attached, as mentioned, to the ideals of the French revolution.[6]

Due to the common arrangement of the colours, at first sight, it seems that the only difference between the Italian and the Mexican flag is only the Aztec coat of arms present in the second; in reality the Italian tricolour uses lighter shades of green and red, and has different proportions than the Mexican flag: those of the Italian flag are equal to 2:3, while the proportions of the Mexican flag are 4:7.[112] The similarity between the two flags posed a serious problem in maritime transport, given that originally the Mexican mercantile flag was devoid of arms and therefore was consequently identical to the Italian Republican tricolour of 1946; to obviate the inconvenience, at the request of the International Maritime Organization, both Italy and Mexico adopted naval flags with different crests.[87]

Also due to the Italian layout, the Italian flag is also quite similar to the flag of Ireland, with the exception of orange instead of red (although the shades used for the two colours are very similar[113]) and proportions (2:3 against 1:2).[114]

The Hungarian flag has the same colours as the Italian one, but this does not create confusion between the banners: on the Magyar flag the red, white and green tricolour is arranged horizontally.[113] Other flags with green, white and red in horizontal bands are those of Bulgaria,[113] Iran,[115] Oman[115] and Tajikistan.[115]

Finally, they present other combinations of the three colours, the banners of Madagascar,[115] Suriname,[115] and Burundi.[115]

See also

- Flags of regions of Italy

- List of Italian flags

- National symbols of Italy

- Sala del Tricolore (Reggio Emilia)

- Tricolour Day

Citations

- Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana Art. 12, 22 dicembre 1947, pubblicata nella Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 298 del 27 dicembre 1947 edizione straordinaria (published in the Official Gazette [of the Italian Republic] No. 298 of 27 December 1947 extraordinary edition) "La bandiera della Repubblica è il tricolore italiano: verde, bianco, e rosso, a tre bande verticali di eguali dimensioni"

- "The Italian Flag (Bandiera d'Italia)". lagazzettaitaliana.com. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Le drapeau français – Présidence de la République" (in French). Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Otto mesi prima di Reggio il tricolore era già una realtà" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "I simboli della Repubblica" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 156.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 662.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). "La vera origine del tricolore italiano". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento (in Italian). XII (fasc. III): 666.

- "I valori – Il Tricolore" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Mostra Giovan Battista De Rolandis e il Tricolore". 150.provincia.asti.it. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Villa Claudio, I simboli della Repubblica: la bandiera tricolore, il canto degli italiani, l'emblema, Comune di Vanzago, 2010, SBN IT\ICCU\LO1\1355389, p. 12

- De Rolandis Ito, Origine del tricolore – Da Bologna a Torino capitale d'Italia, Torino, Il Punto – Piemonte in Bancarella, 1996, ISBN 88-86425-30-9, p. 18

- Giovanni Francesco Damilano, Libro familiare di me sacerdote ed avvocato Giovanni Francesco Damilano 1775-1802, Cherasco, Fondo Adriani, Historical Archive of the City of Cherasco, 1803, p. 36.

- Fiorini, 1897 & p. 688.

- Bovio, 1996 & p. 19.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 67.

- "L'Esercito del primo Tricolore" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 10.

- Busico, 2005 & p. 11.

- "Il significato dei tre colori della nostra Bandiera Nazionale". radiomarconi.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- On 11 October 1796 Napoleon wrote to the Directorate, "Les couleurs nationales qu'ils ont adoptées sont le vert, le blanc et le rouge" (the national colours they have adopted are green, white, and red), Corr. Nap. II, No. 1085; see Frasca, Francesco Les Italiens dans l'Armée napoléonienne: Des légions aux Armées de la République italienne et du Royaume d'Italie Etudes napoléoniennes, Tome IV (pp. 374–396) Levallois: Centre d'études napoléoniennes, 1988

- Colangeli, 1965 & p. 14.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 11.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 68.

- "Bologna, 28 ottobre 1796: Nascita della Bandiera Nazionale Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- The tri-coloured standard.Getting to Know Italy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (retrieved 5 October 2008) Archived 23 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- [...] Dal verbale della Sessione XIV del Congresso Cispadano: Reggio Emilia, 7 gennaio 1797, ore 11. Sala Patriottica. Gli intervenuti sono 100, deputati delle popolazioni di Bologna, Ferrara, Modena e Reggio Emilia. Giuseppe Compagnoni fa pure mozione che si renda Universale lo Stendardo o Bandiera Cispadana di tre colori, Verde, Bianco e Rosso e che questi tre colori si usino anche nella Coccarda Cispadana, la quale debba portarsi da tutti. Viene decretato. [...]

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 169.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 15.

- "Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Bonapartes," facsimile of the 1922 English translation by Aylmer and Louise Maude, Project Gutenberg (retrieved 5 October 2008)

- Regio decreto del 25 marzo 1860; see 1860 — La nuova bandiera dei Corpi di Fanteria e Cavalleria Uniformi e Tradizioni, Ministero della Difesa (retrieved 19 January 2013). Note No. 41 of 16 March 1863 (published in the Official Military Journal) is, in effect, an amendment to the 1860 decree with regard to fortresses, towers and military establishments; see 1863 — Bandiere per le fortezze, torri e stabilimenti militari Uniformi e Tradizioni, Ministero della Difesa (retrieved 22 January 2013)

- Ghisi, Enrico Il tricolore italiano (1796–1870) Milano: Anonima per l'Arte della Stampa, 1931; see Gay, H. Nelson in The American Historical Review Vol. 37 No. 4 (pp. 750–751), July 1932

- "Per viemmeglio dimostrare con segni esteriori il sentimento dell'unione italiana vogliamo che le Nostre truppe ... portino lo scudo di Savoia sovrapposto alla bandiera tricolore italiana." See Lawrence, D. H. (ed. Philip Crumpton) Movements in European History (p. 230) Cambridge University Press, 1989 for an overview

- Lo Statuto Albertino Art. 77, dato in Torino addì quattro del mese di marzo l'anno del Signore mille ottocento quarantotto, e del Regno Nostro il decimo ottavo (given in Turin on the fourth of the month of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty-eight, and of Our Reign the eighteenth)

- Lawrence, op. cit. (p. 229)

- Rostenberg, Leona, "Margaret Fuller's Roman Diary," The Journal of Modern History Vol. 12 No. 2 (pp. 209–220), June 1940

- Villa, 2010 & p. 24.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 196–198.

- Scirocco, Alfonso (trans. Allan Cameron) Garibaldi: Citizen of the World (p. 279) Princeton University Press, 2007

- Regio decreto n. 2072 del 24 settembre 1923, convertito nella legge n. 2264 del 24 dicembre 1923

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 207.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 219.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 247.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 257.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 243.

- Busico, 2005 & p. 65.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 31.

- Mack Smith, Denis Italy and its Monarchy (p. 265) Yale University Press, 1989

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 248.

- Gentile, Emilio The sacralization of politics in fascist Italy (p. 119) Harvard University Press, 1996

- Foggia della bandiera nazionale e della bandiera di combattimento delle Forze Armate decreto legislativo del Duce della Repubblica Sociale Italiana e Capo del Governo n. 141 del 28 gennaio 1944, XXII EF (GU 107 del 6 maggio 1944 XXII EF)

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 267.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 337.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 268.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 273.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 33.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 333.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & pp. 337-338.

- Busico, 2005 & p. 71.

- Tarozzi, 1999 & p. 363.

- Decreto legislativo del capo provvisorio dello stato n. 1305 del 9 novembre 1947 (GU 275 del 29 novembre 1947)

- La Bandiera della Marina Militare Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Le nostre tradizioni, Ministero della Difesa (retrieved 5 October 2008)

- Celebrazione nazionale del bicentenario della prima bandiera nazionale Legge n. 671 del 31 dicembre 1996 (GU 1 del 2 gennaio 1997)

- Article 1 of the law n. 671 of 31 December 1996 ("National celebration of the bicentenary of the first national flag")

- Busico, 2005 & p. 235.

- Ratifica ed esecuzione del Memorandum di Intesa tra il Ministero della difesa della Repubblica italiana e il Comando Supremo delle Forze Alleate in Atlantico riguardo alla bandiera dell’unità per ricerche costiere della NATO, con annesso 1, firmato a Roma il 15 maggio 2001 ed a Norfolk il 20 giugno 2001 Legge n. 321 del 24 ottobre 2003 (GU 271 del 21 novembre 2003)

- Article 1 of the law n. 222 of 23 November 2012 ("Rules on the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the field of" Citizenship and Constitution "and on the teaching of the Mameli hymn in schools")

- https://it.wikisource.org/wiki/Verbali_del_Consiglio_dei_Ministri_della_Repubblica_Sociale_Italiana_settembre_1943_-_aprile_1945/24_novembre_1943

- "La Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Il tricolore" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 35.

- Dopo 206 anni codificati i toni del nostro simbolo nazionale at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 September 2019)

- Stendardo del presidente della Repubblica Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica del 9 ottobre 2000 (GU 241 del 14 ottobre 2000)

- Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica del 9 ottobre 2000 gazzette.comune.jesi.an.it

- Foggia ed uso dell'emblema dello Stato Decreto legislativo n. 535 del 5 maggio 1948 (GU 122 del 28 maggio 1948 suppl. ord.)

- "Lo Stendardo presidenziale" (in Italian). Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Smith, Whitney (1980). Flags and arms across the world. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 110. ISBN 9780070590946. OCLC 4957064.

- web, Segretariato generale della Presidenza della Repubblica – Servizio sistemi informatici – reparto. "I Simboli della Repubblica – lo Stendardo" [The Symbols of the Republic – the Standard]. Il Presidente (in Italian). Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Previous Presidential Standard (1965–1990,1992–2000)". flagspot.net. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- Foglio d'ordini del 11 febbraio 1948

- Foglio d'ordini n. 76 del 22 settembre 1965; Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica del 22 marzo 1990 e del 29 giugno 1992

- Lo Stendardo Presidenziale I Corazzieri, Arma dei Carabinieri (retrieved 5 October 2008)

- "Le funzioni del Presidente della Repubblica, in ogni caso che egli non possa adempierle, sono esercitate dal Presidente del Senato" (the functions of the President of the Republic, in all cases in which he cannot carry them out, shall be exercised by the President of the Senate)

- Insegna distintiva degli ex Presidenti della Repubblica Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica del 17 maggio 2001 (GU 117 del 22 maggio 2001)

- Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica n. 19/N del 14 ottobre 1986

- presidenza.governo.it - Bandiera.pdf

- "La bandiera Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Regio decreto del 22 aprile 1879. After 1893, the proportions were altered from 1:1 to 5:6

- Disposizioni generali sull'uso della bandiera della Repubblica italiana e di quella dell'Unione europea Legge n. 22 del 5 febbraio 1998 (GU 37 del 14 febbraio 1998) e Regolamento recante disciplina dell'uso delle bandiere della Repubblica italiana e dell'Unione europea da parte delle amministrazioni dello Stato e degli enti pubblicie Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica n. 121 del 7 aprile 2000 (GU 112 del 16 maggio 2000)

- Znamierowski, Alfred The World Encyclopedia of Flags London: Lorenz Books, 1999

- The Rules of Protocol regarding national holidays and the use of the Italian flag Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Presidency of the Council of Ministers, Department of Protocol (retrieved 5 October 2008)

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 278.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 280.

- Busico, 2005 & p. 9.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 158.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 13.

- Fiorini, 1897 & pp. 239-267 and 676-710.

- "Il significato dei tre colori della nostra Bandiera Nazionale" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- "Perché la bandiera italiana è verde bianca rossa" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Dal discorso di Giosuè Carducci, tenuto il 7 gennaio 1897 a Reggio Emilia per celebrare il 1° centenario della nascita del Tricolore (from the speech by Giosuè Carducci, held on 7 January 1897 in Reggio Emilia to celebrate the 1st centenary of the birth of the Tricolour), Comitato Guglielmo Marconi International (retrieved 5 October 2008)

- "7 gennaio, ecco la festa del Tricolore" (in Italian). Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- "Al via al Quirinale le celebrazioni per il 2 giugno con il Cambio della Guardia d'onore" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 294-295.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 153-155.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 285.

- "Museo centrale del Risorgimento - Complesso del Vittoriano" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- "Il Sacrario delle Bandiere al Vittoriano" (in Italian). Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Busico, 2005 & p. 207.

- Maiorino, 2002 & pp. 288-289.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 289.

- "Origini della bandiera tricolore italiana" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- "Bandiera Messico" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Maiorino, 2002 & p. 151.

- "Bandiera Irlanda" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Villa, 2010 & p. 39.

References

- Bovio, Oreste (1996). Due secoli di tricolore (in Italian). Ufficio storico dello Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito. SBN IT\ICCU\BVE\0116837.

- Busico, Augusta (2005). Il tricolore: il simbolo la storia (in Italian). Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Dipartimento per l'informazione e l'editoria. SBN IT\ICCU\UBO\2771748.

- Colangeli, Oronzo (1965). Simboli e bandiere nella storia del Risorgimento italiano (PDF) (in Italian). Patron. SBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0395583.

- Fiorini, Vittorio (1897). "Le origini del tricolore italiano". Nuova Antologia di scienze lettere e arti (in Italian). LXVII (fourth series): 239–267 and 676–710. SBN IT\ICCU\UBO\3928254.

- Maiorino, Tarquinio; Marchetti Tricamo, Giuseppe; Zagami, Andrea (2002). Il tricolore degli italiani. Storia avventurosa della nostra bandiera (in Italian). Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-88-04-50946-2.

- Tarozzi, Fiorenza; Vecchio, Giorgio (1999). Gli italiani e il tricolore (in Italian). Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-07163-6.

- Villa, Claudio (2010). I simboli della Repubblica: la bandiera tricolore, il canto degli italiani, l'emblema (in Italian). Comune di Vanzago. SBN IT\ICCU\LO1\1355389.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National flag of Italy. |

- Italy at Flags of the World

- (in Italian) La Bandiera degli italiani Presidenza della Repubblica, Palazzo del Quirinale

- (in Italian) Centro Italiano Studi Vessillologici (Italian Centre for the Study of Vexillology)

.jpg)