Economy of Argentina

Argentina is a developing country. It is the second-largest in South America behind Brazil.[28]

.jpg) | |

| Currency | Argentine peso (ARS) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organizations | WTO, Mercosur, Prosur, Unasur (suspended), G-20 |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

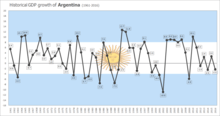

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line |

|

Labor force | |

Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | AR$46,405 monthly (August 2019)[20] |

Main industries |

|

| External | |

| Exports | |

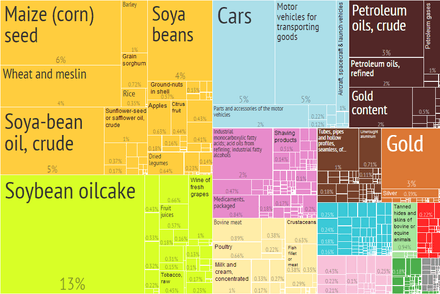

Export goods | Soybeans and derivatives, petroleum and gas, vehicles, corn, wheat |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | Machinery, motor vehicles, petroleum and natural gas, organic chemicals, plastics |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −6% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[19] | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

| |

Foreign reserves |

|

Argentina benefits from rich natural resources, a highly literate population, an export-oriented agricultural sector, and a diversified industrial base. Argentina's economic performance has historically been very uneven, with high economic growth alternating with severe recessions, particularly since the late twentieth century, since when income maldistribution and poverty have increased. Early in the twentieth century Argentina had one of the ten highest per capita GDP levels in the world, on par with Canada and Australia and surpassing both France and Italy.[29]

Argentina's currency declined by about 50% in 2018 to more than 38 Argentine pesos per U.S. Dollar and as of in that year is under a stand-by program from the International Monetary Fund.[30] In 2019, it fell further by 25%.[31]

Argentina is considered an emerging market by the FTSE Global Equity Index (2018),[32] and is one of the G-20 major economies.

History

Prior to the 1880s, Argentina was a relatively isolated backwater, dependent on the salted meat, wool, leather, and hide industries for both the greater part of its foreign exchange and the generation of domestic income and profits. The Argentine economy began to experience swift growth after 1880 through the export of livestock and grain commodities,[33] as well as through British and French investment, marking the beginning of a fifty-year era of significant economic expansion and mass European immigration.[34]

During its most vigorous period, from 1880 to 1905, this expansion resulted in a 7.5-fold growth in GDP, averaging about 8% annually.[35] One important measure of development, GDP per capita, rose from 35% of the United States average to about 80% during that period.[35] Growth then slowed considerably, such that by 1941 Argentina's real per capita GDP was roughly half that of the U.S.[29] Even so, from 1890 to 1950 the country's per capita income was similar to that of Western Europe;[29] although income in Argentina remained considerably less evenly distributed.[33] According to a study by Baten and Pelger and Twrdek (2009), where the authors compare anthropometric values, i.e. height with real wages, Argentina’s GDP did increase for the decades after 1870 and before 1910 however, the heights have been left unaffected. This in turn suggests that the increase in welfare of the population did not take place during income expansion of the given period.[36]

The Great Depression caused Argentine GDP to fall by a fourth between 1929 and 1932. Having recovered its lost ground by the late 1930s partly through import substitution, the economy continued to grow modestly during World War II (in contrast to the recession caused by the previous world war).[37] The war led to a reduced availability of imports and higher prices for Argentine exports that combined to create a US$1.6 billion cumulative surplus,[37] a third of which was blocked as inconvertible deposits in the Bank of England by the Roca–Runciman Treaty.[34] Benefiting from innovative self-financing and government loans alike, value added in manufacturing nevertheless surpassed that of agriculture for the first time in 1943, employed over 1 million by 1947,[38] and allowed the need for imported consumer goods to decline from 40% of the total to 10% by 1950.[34]

The populist administration of Juan Perón nationalized the Central Bank, railways, and other strategic industries and services from 1945 to 1955. The subsequent enactment of developmentalism after 1958, though partial, was followed by a promising fifteen years. Inflation first became a chronic problem during this period[37] (it averaged 26% annually from 1944 to 1974);[39] but though it did not become fully "developed," from 1932 to 1974 Argentina's economy grew almost fivefold (or 3.8% in annual terms) while its population only doubled.[39] While unremarkable, this expansion was well-distributed and so resulted in several noteworthy changes in Argentine society – most notably the development of the largest proportional middle class (40% of the population by the 1960s) in Latin America[39] as well as the region's highest-paid, most unionized working class.[40]

The economy, however, declined during the military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983, and for some time afterwards.[41] The dictatorship's chief economist, José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, advanced a corrupt, anti-labor policy of financial liberalization that increased the debt burden and interrupted industrial development and upward social mobility.[42][43] Over 400,000 companies of all sizes went bankrupt by 1982,[37] and neoliberal economic policies prevailing from 1983 through 2001 failed to reverse the situation.[44][45]

Record foreign debt interest payments, tax evasion, and capital flight resulted in a balance of payments crisis that plagued Argentina with severe stagflation from 1975 to 1990, including a bout of hyperinflation in 1989 and 1990. Attempting to remedy this situation, economist Domingo Cavallo pegged the peso to the U.S. dollar in 1991 and limited the growth in the money supply. His team then embarked on a path of trade liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. Inflation dropped to single digits and GDP grew by one third in four years.[46]

External economic shocks, as well as a dependency on volatile short-term capital and debt to maintain the overvalued fixed exchange rate, diluted benefits, causing erratic economic growth from 1995 and the eventual collapse in 2001.[44] That year and the next, the economy suffered its sharpest decline since 1930; by 2002, Argentina had defaulted on its debt, its GDP had declined by nearly 20% in four years, unemployment reached 25%, and the peso had depreciated 70% after being devalued and floated.[46]

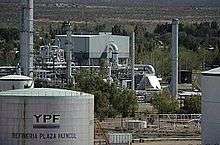

Argentina's socio-economic situation has since been steadily improving. Expansionary policies and commodity exports triggered a rebound in GDP from 2003 onward. This trend has been largely maintained, creating over five million jobs and encouraging domestic consumption and fixed investment. Social programs were strengthened,[47] and a number of important firms privatized during the 1990s were renationalized beginning in 2003. These include the postal service, AySA (the water utility serving Buenos Aires), Pension funds (transferred to ANSES), Aerolíneas Argentinas, the energy firm YPF,[48] and the railways.[49]

The economy nearly doubled from 2002 to 2011, growing an average of 7.1% annually and around 9% for five consecutive years between 2003 and 2007.[46] Real wages rose by around 72% from their low point in 2003 to 2013.[50] The global recession did affect the economy in 2009, with growth slowing to nearly zero;[46] but high economic growth then resumed, and GDP expanded by around 9% in both 2010 and 2011.[46] Foreign exchange controls, austerity measures, persistent inflation, and downturns in Brazil, Europe, and other important trade partners, contributed to slower growth beginning in 2012, however.[51] Growth averaged just 1.3% from 2012 to 2014,[52] and rose to 2.4% in 2015.[6]

The Argentine government bond market is based on GDP-linked bonds, and investors, both foreign and domestic, netted record yields amid renewed growth.[53] Argentine debt restructuring offers in 2005 and 2010 resumed payments on the majority of its almost US$100 billion in defaulted bonds and other debt from 2001.[54]

Holdouts controlling 7% of the bonds, including some small investors, hedge funds, and vulture funds[55][56][57][58] led by Paul Singer's Cayman Islands-based NML Capital Limited, rejected the 2005 and 2010 offers to exchange their defaulted bonds. Singer, who demanded US$832 million for Argentine bonds purchased for US$49 million in the secondary market in 2008,[59] attempted to seize Argentine government assets abroad[60] and sued to stop payments from Argentina to the 93% who had accepted the earlier swaps despite the steep discount.[61] Bondholders who instead accepted the 2005 offer of 30 cents on the dollar, had by 2012 received returns of about 90% according to estimates by Morgan Stanley.[62] Argentina settled with virtually all holdouts in February 2016 at a cost of US$9.3 billion; NML received US$2.4 billion, a 392% return on the original value of the bonds.[63]

While the Argentine Government considers debt left over from illegitimate governments unconstitutional odious debt,[64] it has continued servicing this debt despite the annual cost of around US$14 billion[65] and despite being nearly locked out of international credit markets with annual bond issues since 2002 averaging less than US$2 billion (which precludes most debt roll over).[66]

Argentina has nevertheless continued to hold successful bond issues,[67][68] as the country's stock market, consumer confidence, and overall economy continue to grow.[69][70] The country's successful, US$16.5 billion bond sale in April 2016 was the largest in emerging market history.[71]

In May 2018, Argentina's government asked the International Monetary Fund for its intervention,[72] with an emergency loan for a $30 billion bailout,[73] as reported by Bloomberg.[74]

In May 2018 the official estimated inflation had peaked up to 25 percent a year, and on 4 May[74] Argentina's central bank raised interest rates on pesos to 40 percent from 27.25 percent,[75][73] which is the highest in the world,[76] since the national currency had lost 18% of its value since the beginning of the year.[74]

In 2019 the inflation were considered the highest since 28 years according to indec,[77] ascending to 53,8%.

To cause of the quarantine in 2020, in April, 143,000 SMEs will not be able to pay salaries and fixed expenses for the month, even with government assistance, so they will have to borrow or increase their own capital contribution, and approximately 35,000 companies consider closing their business.[78] even so the president remains firm in his decision to maintain the state of total quarantine. Despite cuts in the payment chain, some project 180 total days, and calculate 5% of companies that fell in May.[79]

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2018. Inflation below 5% is in green.[80]

| Year | GDP (in Bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita 2011 constant price (in US$ PPP) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in Percent) |

Unemployment (in Percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 176.6 | 6,318 | 14,709 | n/a | 3.0% | n/a | |

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1982 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1983 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1984 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1985 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1986 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1987 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1988 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1989 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1990 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1991 | n/a | n/a | |||||

| 1992 | n/a | 25.7% | |||||

| 1993 | n/a | ||||||

| 1994 | n/a | ||||||

| 1995 | n/a | ||||||

| 1996 | n/a | ||||||

| 1997 | n/a | ||||||

| 1998 | |||||||

| 1999 | |||||||

| 2000 | |||||||

| 2001 | |||||||

| 2002 | |||||||

| 2003 | |||||||

| 2004 | |||||||

| 2005 | |||||||

| 2006 | |||||||

| 2007 | |||||||

| 2008 | |||||||

| 2009 | |||||||

| 2010 | |||||||

| 2011 | |||||||

| 2012 | |||||||

| 2013 | |||||||

| 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | |||||||

| 2016 | |||||||

| 2017 | |||||||

| 2018 |

Sectors

Agriculture

Argentina is one of the world's major agricultural producers, ranking among the top producers in most of the following, exporters of beef, citrus fruit, grapes, honey, maize, sorghum, soybeans, squash, sunflower seeds, wheat, and yerba mate.[82] Agriculture accounted for 9% of GDP in 2010, and around one fifth of all exports (not including processed food and feed, which are another third). Commercial harvests reached 103 million tons in 2010, of which over 54 million were oilseeds (mainly soy and sunflower), and over 46 million were cereals (mainly maize, wheat, and sorghum).[83]

Soy and its byproducts, mainly animal feed and vegetable oils, are major export commodities with one fourth of the total; cereals added another 10%. Cattle-raising is also a major industry, though mostly for domestic consumption; beef, leather and dairy were 5% of total exports.[84] Sheep-raising and wool are important in Patagonia, though these activities have declined by half since 1990. Biodiesel, however, has become one of the fastest growing agro-industrial activities, with over US$2 billion in exports in 2011.[84]

Fruits and vegetables made up 4% of exports: apples and pears in the Río Negro valley; rice, oranges and other citrus in the northwest and Mesopotamia; grapes and strawberries in Cuyo (the west), and berries in the far south. Cotton and tobacco are major crops in the Gran Chaco, sugarcane and chile peppers in the northwest, and olives and garlic in the west. Yerba mate tea (Misiones), tomatoes (Salta) and peaches (Mendoza) are grown for domestic consumption. Organic farming is growing in Argentina, and the nearly 3 million hectares (7.5 million acres) of organic cultivation is second only to Australia.[85] Argentina is the world's fifth-largest wine producer, and fine wine production has taken major leaps in quality. A growing export, total viticulture potential is far from having been met. Mendoza is the largest wine region, followed by San Juan.[86]

Government policy towards the lucrative agrarian sector is a subject of, at times, contentious debate in Argentina. A grain embargo by farmers protesting an increase in export taxes for their products began in March 2008,[87] and, following a series of failed negotiations, strikes and lockouts largely subsided only with the 16 July, defeat of the export tax-hike in the Senate.[88]

Argentine fisheries bring in about a million tons of catch annually,[46] and are centered on Argentine hake, which makes up 50% of the catch; pollock, squid, and centolla crab are also widely harvested. Forestry has long history in every Argentine region, apart from the pampas, accounting for almost 14 million m³ of roundwood harvests.[89] Eucalyptus, pine, and elm (for cellulose) are also grown, mainly for domestic furniture, as well as paper products (1.5 million tons). Fisheries and logging each account for 2% of exports.[46]

Natural resources

Mining and other extractive activities, such as gas and petroleum, are growing industries, increasing from 2% of GDP in 1980 to around 4% today.[46] The northwest and San Juan Province are the main regions of activity. Coal is mined in Santa Cruz Province. Metals and minerals mined include borate, copper, lead, magnesium, sulfur, tungsten, uranium, zinc, silver, titanium, and gold, whose production was boosted after 1997 by the Bajo de Alumbrera mine in Catamarca Province and Barrick Gold investments a decade later in San Juan. Metal ore exports soared from US$200 million in 1996 to US$1.2 billion in 2004,[92] and to over US$3 billion in 2010.[84]

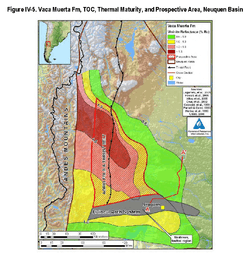

Around 35 million m³ each of petroleum and petroleum fuels are produced, as well as 50 billion m³ of natural gas, making the nation self-sufficient in these staples, and generating around 10% of exports.[46] The most important oil fields lie in Patagonia and Cuyo. A network of pipelines (next to Mexico's, the second-longest in Latin America) send raw product to Bahía Blanca, center of the petrochemical industry, and to the La Plata-Greater Buenos Aires-Rosario industrial belt.

Argentina has significant renewable energy resources. The country will be potentially among the main winners in the global transition to renewable energy; it is ranked no. 10 out of 156 countries in the index of geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition (GeGaLo Index).[93]

Industry

Manufacturing is the largest single sector in the nation's economy (15% of GDP), and is well-integrated into Argentine agriculture, with half the nation's industrial exports being agricultural in nature.[84] Based on food processing and textiles during its early development in the first half of the 20th century, industrial production has become highly diversified in Argentina.[94] Leading sectors by production value are: Food processing and beverages; motor vehicles and auto parts; refinery products, and biodiesel; chemicals and pharmaceuticals; steel and aluminium; and industrial and farm machinery; electronics and home appliances. These latter include over three million big ticket items, as well as an array of electronics, kitchen appliances and cellular phones, among others.[46]

Argentina's auto industry produced 791,000 motor vehicles in 2013, and exported 433,000 (mainly to Brazil, which in turn exported a somewhat larger number to Argentina); Argentina's domestic new auto market reached a record 964,000 in 2013.[95] Beverages are another significant sector, and Argentina has long been among the top five wine producing countries in the world; beer overtook wine production in 2000, and today leads by nearly two billion liters a year to one.[46] Other manufactured goods include: glass and cement; plastics and tires; lumber products; textiles; tobacco products; recording and print media; furniture; apparel and leather.[46]

Most manufacturing is organized in the 314 industrial parks operating nationwide as of 2012, a fourfold increase over the past decade.[96] Nearly half the industries are based in the Greater Buenos Aires area, although Córdoba, Rosario, and Ushuaia are also significant industrial centers; the latter city became the nation's leading center of electronics production during the 1980s.[97] The production of computers, laptops, and servers grew by 160% in 2011, to nearly 3.4 million units, and covered two-thirds of local demand.[98] Argentina has also become an important manufacturer of cell phones, providing about 80% of all devices sold in the country.[99] Farm machinery, another important rubric historically dominated by imports, was similarly replaced by domestic production, which covered 60% of demand by 2013.[100] Production of cell phones, computers, and similar products is actually an "assembly" industry, with the majority of the higher technology components being imported, and the designs of products originating from foreign countries. High labour costs for Argentina assembly work tend to limit product sales penetration to Latin America, where regional trade treaties exist.

Construction permits nationwide covered over 15 million m² (160 million ft²) in 2013. The construction sector accounts for over 5% of GDP, and two-thirds of construction is for residential buildings.[101]

Argentine electric output totaled over 133 billion Kwh in 2013.[46] This was generated in large part through well developed natural gas and hydroelectric resources. Nuclear energy is also of high importance,[102] and the country is one of the largest producers and exporters, alongside Canada and Russia of cobalt-60, a radioactive isotope widely used in cancer therapy.

Services

The service sector is the largest contributor to total GDP, accounting for over 60%. Argentina enjoys a diversified service sector, which includes well-developed social, corporate, financial, insurance, real estate, transport, communication services, and tourism.

The telecommunications sector has been growing at a fast pace, and the economy benefits from widespread access to communications services. These include: 77% of the population with access to mobile phones,[103] 95% of whom use smartphones;[104] Internet (over 32 million users, or 75% of the population);[105] and broadband services (accounting for nearly all 14 million accounts).[106] Regular telephone services, with 9.5 million lines,[107] and mail services are also robust. Total telecom revenues reached more than $17.8 billion in 2013,[108] and while only one in three retail stores in Argentina accepted online purchases in 2013 E-commerce reached US$4.5 billion in sales.[109]

Trade in services remained in deficit, however, with US$15 billion in service exports in 2013 and US$19 billion in imports.[23] Business Process Outsourcing became the leading Argentine service export, and reached US$3 billion.[110] Advertising revenues from contracts abroad were estimated at over US$1.2 billion.[111]

Tourism is an increasingly important sector and provided 4% of direct economic output (over US$17 billion) in 2012; around 70% of tourism sector activity by value is domestic.[112]

Banking

.jpg)

Argentine banking, whose deposits exceeded US$120 billion in December 2012,[113] developed around public sector banks, but is now dominated by the private sector. The private sector banks account for most of the 80 active institutions (over 4,000 branches) and holds nearly 60% of deposits and loans, and as many foreign-owned banks as local ones operate in the country.[114] The largest bank in Argentina by far, however, has long been the public Banco de la Nación Argentina. Not to be confused with the Central Bank, this institution now accounts for 30% of total deposits and a fifth of its loan portfolio.[114]

During the 1990s, Argentina's financial system was consolidated and strengthened. Deposits grew from less than US$15 billion in 1991 to over US$80 billion in 2000, while outstanding credit (70% of it to the private sector) tripled to nearly US$100 billion.[115]

The banks largely lent US dollars and took deposits in Argentine pesos, and when the peso lost most of its value in early 2002, many borrowers again found themselves hard pressed to keep up. Delinquencies tripled to about 37%.[115] Over a fifth of deposits had been withdrawn by December 2001, when Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo imposed a near freeze on cash withdrawals. The lifting of the restriction a year later was bittersweet, being greeted calmly, if with some umbrage, at not having these funds freed at their full U.S. dollar value.[116] Some fared worse, as owners of the now-defunct Velox Bank defrauded their clients of up to US$800 million.[117]

Credit in Argentina is still relatively tight. Lending has been increasing 40% a year since 2004, and delinquencies are down to less than 2%.[113] Still, credit outstanding to the private sector is, in real terms, slightly below its 1998 peak,[115] and as a percent of GDP (around 18%)[113] quite low by international standards. The prime rate, which had hovered around 10% in the 1990s, hit 67% in 2002. Although it returned to normal levels quickly, inflation, and more recently, global instability, have been affecting it again. The prime rate was over 20% for much of 2009, and around 17% since the first half of 2010.[113]

Partly a function of this and past instability, Argentines have historically held more deposits overseas than domestically. The estimated US$173 billion in overseas accounts and investment exceeded the domestic monetary base (M3) by nearly US$10 billion in 2012.[23]

Tourism

According to World Economic Forum's 2017 Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report, tourism generated over US$22 billion, or 3.9% of GDP, and the industry employed more than 671,000 people, or approximately 3.7% of the total workforce.[118] Tourism from abroad contributed US$5.3 billion, having become the third largest source of foreign exchange in 2004. Around 5.7 million foreign visitors arrived in 2017, reflecting a doubling in visitors since 2002 despite a relative appreciation of the peso.[112]

Argentines, who have long been active travelers within their own country,[119] accounted for over 80%, and international tourism has also seen healthy growth (nearly doubling since 2001).[112] Stagnant for over two decades, domestic travel increased strongly in the last few years,[120] and visitors are flocking to a country seen as affordable, exceptionally diverse, and safe.[121]

Foreign tourism, both to and from Argentina, is increasing as well. INDEC recorded 5.2 million foreign tourist arrivals and 6.7 million departures in 2013; of these, 32% arrived from Brazil, 19% from Europe, 10% from the United States and Canada, 10% from Chile, 24% from the rest of the Western Hemisphere, and 5% from the rest of the world. Around 48% of visitors arrived by commercial flight, 40% by motor travel (mainly from neighboring Brazil), and 12% by sea.[122] Cruise liner arrivals are the fastest growing type of foreign tourism to Argentina; a total of 160 liners carrying 510,000 passengers arrived at the Port of Buenos Aires in 2013, an eightfold increase in a just a decade.[123]

GDP by value added

| Supply sector (% of GDP in current prices)[46] | 1993–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009[N 1] | 2010–2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | 5.4 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 |

| Mining | 2.0 | 5.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 |

| Manufacturing | 18.5 | 23.2 | 19.8 | 16.8 |

| Public utilities | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Construction | 5.5 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 5.6 |

| Commerce and tourism | 17.3 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 14.4 |

| Transport and communications | 8.3 | 8.7 | 7.3 | 6.7 |

| Financial services | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 |

| Real estate and business services | 16.5 | 11.7 | 13.7 | 12.9 |

| Public administration and defense | 6.3 | 5.4 | 5.6 | 7.4 |

| Health and education | 8.4 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 11.9 |

| Personal and other services | 5.4 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 6.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

- New methodology; not strictly comparable to earlier data

Energy

Electricity generation in Argentina totaled 133.3 billion Kwh in 2013.[46] The electricity sector in Argentina constitutes the third largest power market in Latin America. It mainly still relies on centralised generation by natural gas power generation (51%), hydroelectricity (28%), and oil-fired generation (12%).[124] Reserves of shale gas and tight oil in the Vaca Muerta oil field and elsewhere are estimated to be the world's third-largest.[90]

Despite the country's large untapped wind and solar potential new renewable energy technologies and distributed energy generation are barely exploited. Wind energy is the fastest growing among new renewable sources. Fifteen wind farms have been developed since 1994 in Argentina, the only country in the region to produce wind turbines. The 55 MW of installed capacity in these in 2010 will increase by 895 MW upon the completion of new wind farms begun that year.[125] Solar power is being promoted with the goal of expanding installed solar capacity from 6 MW to 300, and total renewable energy capacity from 625 MW to 3,000 MW.[126]

Argentina is in the process of commissioning large centralised energy generation and transmission projects. An important number of these projects are being financed by the government through trust funds, while independent private initiative is limited as it has not fully recovered yet from the effects of the Argentine economic crisis.

The first of the three nuclear reactors was inaugurated in 1974, and in 2015 nuclear power generated 5% of the country's energy output.[124]

The electricity sector was unbundled in generation, transmission and distribution by the reforms carried out in the early 1990s. Generation occurs in a competitive and mostly liberalized market, in which 75% of the generation capacity is owned by private utilities. In contrast, the transmission and distribution sectors are highly regulated and much less competitive than generation.

Infrastructure

.jpg)

Argentina's transport infrastructure is relatively advanced, and at a higher standard than the rest of Latin America.[127] There are over 230,000 km (144,000 mi) of roads (not including private rural roads) of which 72,000 km (45,000 mi) are paved,[128] and 2,800 kilometres (1,700 mi) are expressways, many of which are privatized tollways.[129] Having tripled in length in the last decade, multilane expressways now connect several major cities with more under construction.[129][130] Expressways are, however, currently inadequate to deal with local traffic,[130] as over 12 million motor vehicles were registered nationally as of 2012 (the highest, proportionately, in the region).[131]

The railway network has a total length of 37,856 kilometres (23,523 mi), though at the network's peak this figure was 47,000 km (29,204 mi).[85][132] After decades of declining service and inadequate maintenance, most intercity passenger services shut down in 1992 following the privatization of the country's railways and the breaking up of the state rail company, while thousands of kilometers fell into disuse. Outside Greater Buenos Aires most rail lines still in operation are freight related, carrying around 23 million tons a year.[46][133] The metropolitan rail lines in and around Buenos Aires remained in great demand owing in part to their easy access to the Buenos Aires Underground, and the commuter rail network with its 833 kilometres (518 mi) length carries around 1.4 million passengers daily.[134]

In April 2015, by overwhelming majority the Argentine Senate passed a law which re-created Ferrocarriles Argentinos as Nuevos Ferrocarriles Argentinos, effectively re-nationalising the country's railways.[135][136][137] In the years leading up to this move, the country's railways had seen significant investment from the state, purchasing new rolling stock, re-opening lines closed under privatization and re-nationalising companies such as the Belgrano Cargas freight operator.[138][139][140][141] Some of these re-opened services include the General Roca Railway service to Mar del Plata, the Tren a las Nubes tourist train and the General Mitre Railway service from Buenos Aires to Córdoba.[142][143][144] while brand new services include the Posadas-Encarnación International Train.[145]

Inaugurated in 1913, the Buenos Aires Underground was the first underground rail system built in Latin America, the Spanish speaking world and the Southern Hemisphere.[146] No longer the most extensive in South America, its 60 kilometres (37 mi) of track carry a million passengers daily.[147]

Argentina has around 11,000 km (6,835 mi) of navigable waterways, and these carry more cargo than do the country's freight railways.[148] This includes an extensive network of canals, though Argentina is blessed with ample natural waterways as well, the most significant among these being the Río de la Plata, Paraná, Uruguay, Río Negro, and Paraguay rivers. The Port of Buenos Aires, inaugurated in 1925, is the nation's largest; it handled 11 million tons of freight and transported 1.8 million passengers in 2013.[123]

Aerolíneas Argentinas is the country's main airline, providing both extensive domestic and international service. Austral Líneas Aéreas is Aerolíneas Argentinas' subsidiary, with a route system that covers almost all of the country. LADE is a military-run commercial airline that flies extensive domestic services. The nation's 33 airports handled air travel totalling 25.8 million passengers in 2013, of which domestic flights carried over 14.5 million; the nation's two busiest airports, Jorge Newbery and Ministro Pistarini International Airports, boarded around 9 million flights each.[149]

Foreign trade

Argentine exports are fairly well diversified. However, although agricultural raw materials are over 20% of the total exports, agricultural goods still account for over 50% of exports when processed foods are included. Soy products alone (soybeans, vegetable oil) account for almost one fourth of the total. Cereals, mostly maize and wheat, which were Argentina's leading export during much of the twentieth century, make up less than one tenth now.[150]

Industrial goods today account for over a third of Argentine exports. Motor vehicles and auto parts are the leading industrial export, and over 12% of the total merchandise exports. Chemicals, steel, aluminum, machinery, and plastics account for most of the remaining industrial exports. Trade in manufactures has historically been in deficit for Argentina, however, and despite the nation's overall trade surplus, its manufacturing trade deficit exceeded US$30 billion in 2011.[151] Accordingly, the system of non-automatic import licensing was extended in 2011,[152] and regulations were enacted for the auto sector establishing a model by which a company's future imports would be determined by their exports (though not necessarily in the same rubric).[153]

A net energy importer until 1987, Argentina's fuel exports began increasing rapidly in the early 1990s and today account for about an eighth of the total; refined fuels make up about half of that. Exports of crude petroleum and natural gas have recently been around US$3 billion a year.[150] Rapidly growing domestic energy demand and a gradual decline in oil production, resulted in a US$3 billion energy trade deficit in 2011 (the first in 17 years)[154] and a US$6 billion energy deficit in 2013.[155]

Argentine imports have historically been dominated by the need for industrial and technological supplies, machinery, and parts, which have averaged US$50 billion since 2011 (two-thirds of total imports). Consumer goods including motor vehicles make up most of the rest.[150] Trade in services has historically in deficit for Argentina, and in 2013 this deficit widened to over US$4 billion with a record US$19 billion in service imports.[23] The nation's chronic current account deficit was reversed during the 2002 crisis, and an average current account surplus of US$7 billion was logged between 2002 and 2009; this surplus later narrowed considerably, and has been slightly negative since 2011.[156]

Foreign investment

Foreign direct investment in Argentina is divided nearly evenly between manufacturing (36%), natural resources (34%), and services (30%). The chemical and plastics sector (10%) and the automotive sector (6%) lead foreign investment in local manufacturing; oil and gas (22%) and mining (5%), in natural resources; telecommunications (6%), finance (5%), and retail trade (4%), in services.[157] Spain was the leading source of foreign direct investment in Argentina, accounting for US$22 billion (28%) in 2009; the U.S. was the second leading source, with $13 billion (17%);[157] and China grew to become the third-largest source of FDI by 2011.[158] Investments from the Netherlands, Brazil, Chile, and Canada have also been significant; in 2012, foreign nationals held a total of around US$112 billion in direct investment.[23]

Several bilateral agreements play an important role in promoting U.S. private investment. Argentina has an Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) agreement and an active program with the U.S. Export-Import Bank. Under the 1994 U.S.–Argentina Bilateral Investment Treaty, U.S. investors enjoy national treatment in all sectors except shipbuilding, fishing, nuclear-power generation, and uranium production. The treaty allows for international arbitration of investment disputes.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Argentina, which averaged US$5.7 billion from 1992 to 1998 and reached in US$24 billion in 1999 (reflecting the purchase of 98% of YPF stock by Repsol), fell during the crisis to US$1.6 billion in 2003.[159] FDI then accelerated, reaching US$8 billion in 2008.[160] The global crisis cut this figure to US$4 billion in 2009; but inflows recovered to US$6.2 billion in 2010.[161] and US$8.7 billion in 2011, with FDI in the first half of 2012 up by a further 42%.[162]

FDI volume remained below the regional average as a percent of GDP even as it recovered, however; Kirchner Administration policies and difficulty in enforcing contractual obligations had been blamed for this modest performance.[163] The nature of foreign investment in Argentina nevertheless shifted significantly after 2000, and whereas over half of FDI during the 1990s consisted in privatizations and mergers and acquisitions, foreign investment in Argentina became the most technologically oriented in the region – with 51% of FDI in the form of medium and high-tech investment (compared to 36% in Brazil and 3% in Chile).[164]

Issues

The economy recovered strongly from the 2001–02 crisis, and was the 21st largest in purchasing power parity terms in 2011; its per capita income on a purchasing power basis was the highest in Latin America.[52] A lobby representing US creditors who refused to accept Argentina's debt-swap programmes has campaigned to have the country expelled from the G20.[165] These holdouts include numerous vulture funds which had rejected the 2005 offer, and had instead resorted to the courts in a bid for higher returns on their defaulted bonds. These disputes had led to a number of liens against central bank accounts in New York and, indirectly, to reduced Argentine access to international credit markets.[166]

The government under President Mauricio Macri announced to be seeking a new loan from the International Monetary Fund in order to avoid another economic crash similar to the one in 2001.[167] The May 2018 announcement comes at a time of high inflation and falling interest rates.[167] The loan would reportedly be worth $30 billion.[168]

Following 25 years of boom and bust stagnation, Argentina's economy doubled in size from 2002 to 2013,[52] and officially, income poverty declined from 54% in 2002 to 5% by 2013;[169] an alternative measurement conducted by CONICET found that income poverty declined instead to 15.4%.[170] Poverty measured by living conditions improved more slowly, however, decreasing from 17.7% in the 2001 Census to 12.5% in the 2010 Census.[171] Argentina's unemployment rate similarly declined from 25% in 2002 to an average of around 7% since 2011 largely because of both growing global demand for Argentine commodities and strong growth in domestic activity.[172]

Given its ongoing dispute with holdout bondholders, the government has become wary of sending assets to foreign countries (such as the presidential plane, or artworks sent to foreign exhibitions) in case they might be impounded by courts at the behest of holdouts.[173]

The government has been accused of manipulating economic statistics.[174]

Reliability of official CPI estimates

Official CPI inflation figures released monthly by INDEC have been a subject of political controversy since 2007 through 2015.[172][175][176] Official inflation data are disregarded by leading union leaders, even in the people sector, when negotiating pay rises.[177] Some private-sector estimates put inflation for 2010 at around 25%, much higher than the official 10.9% rate for 2010.[177] Inflation estimates from Argentina's provinces are also higher than the government's figures.[177] The government backed up the validity of its data, but has called in the International Monetary Fund to help it design a new nationwide index to replace the current one.[177]

The official government CPI is calculated based on 520 products, however the controversy arises from these products not being specified, and thus how many of those products are subject to price caps and subsidies.[178] Economic analysts have been prosecuted for publishing estimates that disagree with official statistics.[179] The government enforces a fine of up to 500,000 pesos for providing what it calls "fraudulent inflation figures".[177] Beginning in 2015, the government again began to call for competitive bids from the private sector to provide a weekly independent inflation index.[180]

Inflation

High inflation has been a weakness of the Argentine economy for decades.[181] Inflation has been unofficially estimated to be running at around 25% annually since 2008, despite official statistics indicating less than half that figure;[182][183] these would be the highest levels since the 2002 devaluation.[181] A committee was established in 2010 in the Argentine Chamber of Deputies by opposition Deputies Patricia Bullrich, Ricardo Gil Lavedra, and others to publish an alternative index based on private estimates.[51] Food price increases, particularly that of beef, began to outstrip wage increases in 2010, leading Argentines to decrease beef consumption per capita from 69 kg (152 lb) to 57 kg (125 lb) annually and to increase consumption of other meats.[181][184]

Consumer inflation expectations of 28 to 30% led the national mint to buy banknotes of its highest denomination (100 pesos) from Brazil at the end of 2010 to keep up with demand. The central bank pumped at least 1 billion pesos into the economy in this way during 2011.[185]

As of June 2015, the government said that inflation was at 15.3%;[186] approximately half that of some independent estimates.[187] Inflation remained at around 18.6% in 2015 according to an International Monetary Fund estimate;[188] but following a sharp devaluation enacted by the Mauricio Macri administration on 17 December, inflation reignited during the first half of 2016 – reaching 42% according to the Finance Ministry.[189]

Supermarkets in Argentina have adopted electronic price tags, allowing prices to be updated quicker.[190]

In the second quarter of 2019, reports suggested that the economy of the country is sinking, inflation is rising and the currency is depreciating. Despite the country receiving one of the largest IMF financial support programmes ever given to any nation, Argentina's poverty rose to 32% from 26% the previous year.[191][192] In August 2019, as an attempt to stabilise the economy, the government decided to impose restrictions on foreign currency purchases.[193]

Income distribution

In relation to other Latin American countries, Argentina has a moderate to low level of income inequality. Its Gini coefficient is of about 0.427 (2014).[194] The social gap is worst in the suburbs of the capital, where beneficiaries of the economic rebound live in gated communities, and many of the poor live in slums known as villas miserias.[195]

In the mid-1970s, the most affluent 10% of Argentina's population had an income 12 times that of the poorest 10%. That figure had grown to 18 times by the mid-1990s, and by 2002, the peak of the crisis, the income of the richest segment of the population was 43 times that of the poorest.[195] These heightened levels of inequality had improved to 26 times by 2006,[196] and to 16 times at the end of 2010.[197] Economic recovery after 2002 was thus accompanied by significant improvement in income distribution: in 2002, the richest 10% absorbed 40% of all income, compared to 1.1% for the poorest 10%;[198] by 2010, the former received 29% of income, and the latter, 1.8%.[197]

Argentina has an inequality-adjusted human development index of 0.707, compared to 0.578 and 0.710 for neighboring Brazil and Chile, respectively.[199] The 2010 Census found that poverty by living conditions still affect 1 in 8 inhabitants, however;[171] and while the official, household survey income poverty rate (based on U$S 100 per person per month, net) was 4.7% in 2013,[169] the National Research Council estimated income poverty in 2010 at 22.6%,[170] with private consulting firms estimating that in 2011 around 21% fell below the income poverty line.[200] The World Bank estimated that, in 2013, 3.6% subsisted on less than US$3.10 per person per day.[201]

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population, total". World Bank. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Global Economic Prospects, June 2020". openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 86. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Indec" (PDF) (in Spanish). Indec. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "Índice de precios al consumidor" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. 15 January 2019. p. 3.

- "Índice de precios al consumidor" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. 11 January 2018. p. 3.

- "Un informe de la UCA marca que la pobreza en Argentina trepó al 33%" (in Spanish). Universidad Católica Argentina. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) – Argentina". World Bank. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $5.50 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) – Argentina". World Bank. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". World Bank. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Labor force, total – Argentina". World Bank. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) – Argentina". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Empleo e Ingresos". MECON.

- https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/mercado_trabajo_eph_4trim19EDC756AEAE.pdf

- "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Tablero de la Economía Real – Ministerio de Producción". tableromer.produccion.gob.ar.

- "Ease of Doing Business in Argentina". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/i_argent_02_207C5EA3BCD1.pdf

- "Economic and financial data for Argentina". MECON. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "La deuda argentina ya se acerca al 97,7% del PBI del país y es la más alta de la región" (in Spanish). Infobae. 10 February 2019.

- "Finanzas Públicas". Ministerio de Economía.

- "Gasto Público por finalidad, función". INDEC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "S&P raises Argentina local currency ratings 'B-/B' with a stable outlook". FTSE Global Markets. 4 February 2016.

- Devereux, Charlie (18 September 2015). "Argentina's Economy Expanded 2.3% in Second Quarter". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "New Maddison Project Database". The Maddison-Project. 2013.

- Olivera Doll, Ignacio (16 January 2019). "The Four Weapons Argentina Has to Avoid a New Storm in 2019". Bloomberg. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Argentine Peso Claws Back after Three Days of Grim Losses". Reuters.

- "FTSE Country Classification – March 2018 Interim Update" (PDF). FTSE.

- Johnson, Lyman. Distribution of Wealth in 19th century Buenos Aires Province. Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1994.

- Rock, David (1987). Argentina: 1516–1987. University of California Press.

- "Ingreso per cápita relativo 1875–2006". Jorge Ávila. 25 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Baten, Joerg; Pelger, Ines; Twrdek, Linda (December 2009). "The anthropometric history of Argentina, Brazil and Peru during the 19th and early 20th century". Economics & Human Biology. 7 (3): 319–333. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2009.04.003. PMID 19451040.

- Lewis, Paul (1990). The Crisis of Argentine Capitalism. University of North Carolina Press.

- Demographic Yearbook 1956 (PDF). UN. p. 362.

- The Statistical Abstract of Latin America. University of California, Los Angeles.

- Nelson, Daniel, ed. (2003). St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide. St. James Press.

- "Argentina – Economic development". Nationsencyclopedia.com.

- Keith B. Griffin (1989). Alternative strategies for economic development. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Centre. St. Martin's Press. p. 59.

- "El derrumbe de salarios y la plata dulce". Clarín. 24 March 2006. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Blustein, Paul; Tulchin, Joseph (June 2002). "A Social Contract Abrogated: Argentina's Economic Crisis" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson Center.

- Monserrat Llairó; María de (May 2006). "La crisis del estado benefactor y la imposición neoliberal en la Argentina de Alfonsín y Menem". Aldea Mundo.

- "Nivel de actividad". Economy Ministry.

- Tirenni, Jorge (May 2013). "La política social argentina ante los desafíos de un Estado inclusivo (2003–2013)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "Reestatizaciones: un camino que empezó Kirchner en 2003". Clarín.

- "Senate passes railway nationalisation into law". Buenos Aires Herald. 15 April 2015.

- "El poder adquisitivo creció 72% desde 2003". Tiempo Argentino. 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014.

- "Argentina says inflation accelerated as economy cooled". Reuters. 15 January 2013.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "El PBI subió 8,5% en 2010 y asegura pago récord de u$s 2.200 millones a inversores". El Cronista Comercial. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011.

- Richard Wray (16 April 2010). "Argentina to repay 2001 debt as Greece struggles to avoid default". The Guardian.

- "Vulture funds: Why the UK voted 'no' to action at the UN – dissected". Jubilee Debt Campaign. 14 November 2014.

- "UN urged to swoop on vulture funds". The Guardian. 2 September 2014.

- "'Vulture' hedge funds set to target unprotected government debt". Financial Times. 26 November 2014.

- "The end of vulture funds?". Al Jazeera. 22 March 2014.

- "Argentina's debt battle: why the vulture funds are circling". Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. 3 July 2014.

- "The real story behind the Argentine vessel in Ghana and how hedge funds tried to seize the presidential plane". Forbes.

- "Argentina's 'vulture fund' crisis threatens profound consequences for international financial system". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 25 June 2014.

- Drew Benson. "Billionaire Hedge Funds Snub 90% Returns". Bloomberg News.

- "How Argentina settled a billion-dollar debt dispute with hedge funds". The New York Times. 25 April 2016.

- Michalowski, Dr Sabine (2007). Unconstitutional Regimes and the Validity of Sovereign Debt: A Legal Perspective. Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 90. ISBN 978-0754647935.

- "Debt service on external debt, total (TDS, current US$)". World Bank.

- J.F.Hornbeck (6 February 2013). "Argentina's Defaulted Sovereign Debt: Dealing with the "Holdouts"" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 14.

- "Gov't defies 'vultures' with dollar bond issue". Buenos Aires Herald. 22 April 2015.

- "Buenos Aires Province exchanges bonds, eases refinancing pressure". Reuters. 10 June 2015.

- "Is Argentina's economy pulling a tango turnaround?". CNN. 7 May 2015.

- "World Bank forecasts Argentina will regain access to capital markets in 2017". MercoPress. 12 June 2015.

- "Argentina's triumphant return to international capital markets". Forbes. 30 April 2016.

- "Argentina seeks IMF help, opposition says bad move". Al Jazeera. 11 May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Is the next global financial crisis brewing?". 13 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

In 2017, inflows to 25 of these countries totaled $1.2 trillion

- "Les raisons qui poussent l'Argentine à appeler le FMI au secours". Le Monde (in French). 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Qué tiene que ver Estados Unidos en la crisis del peso en Argentina y qué lecciones puede sacar América Latina" (in Spanish). New York. 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "L'Argentine fait face à de nouvelles turbulences financières". Le Monde (in French). 5 May 2018. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "En 2019 la inflación saltó a 53,8% y fue la más alta de los últimos 28 años". clarin.com.

- "Coronavirus. Hay 35.000 pymes que están considerando cerrar su negocio". lanacion.com.ar. 8 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus: empresarios advierten que si sigue la cuarentena las empresas requerirán más salvataje del Gobierno". El Cronista.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. 3 March 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Wine pg 300–301 Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4

- FAO

- Récords en cosechas y exportación de granos Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- "Argentine Foreign Trade (2015)" (PDF). INDEC. 18 February 2016.

- The Statesman's Yearbook. Macmillan Publishers. 2009.

- "La Franco Argentine VINS ARGENTINS". francoargentine.com.

- "Store shelves grow bare as Argentine farmers continue strike". CNN.

- "Crisis política: sorpresivo voto del vice Cobos contra las retenciones móviles kirchneristas". Clarín. 16 July 2008.

- "ESS Website ESS : Statistics home". fao.org.

- Fontevecchia, Agustino (14 September 2012). "Big Oil Close To Argentina's YPF: Chevron And Others Don't Fear Nationalization". Forbes.

- "Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States" (PDF). U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). June 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "Investing in Argentina: Mining" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2006. Economy Ministry of Argentina (in Spanish)

- Overland, Indra; Bazilian, Morgan; Ilimbek Uulu, Talgat; Vakulchuk, Roman; Westphal, Kirsten (2019). "The GeGaLo index: Geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition". Energy Strategy Reviews. 26: 100406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406

- "Evolución de la industria nacional argentina". Gestiopolis.

- "Informe Industria, diciembre 2013". ADEFA. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- "Ministra argentina: pasamos de 80 a 314 parques industriales". América Economía.

- "Fernandez_pichetto_2014-12-03". 3 December 2014.

- "Creció un 161% la producción de computadoras en 2011". Tiempo Argentino. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

- "Latin America's – telecoms, mobile and broadband overview shared in new research report". Whatech. 3 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- "El 60% de la maquinaria agrícola vendida es de producción nacional". Argentina en Noticias. 7 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Permisos de edificación otorgados y superficie cubierta autorizada por tipo de construcción". INDEC. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- CNEA: Themes in Nuclear Energy and Physics Archived 2 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "El uso de dispositivos móviles crece en la Argentina y entusiasma a los anunciantes". iProfesional. 11 April 2011.

- "El 95% de los usuarios móviles de Internet entra a redes sociales". Cronista. 17 February 2015.

- "Argentina Internet Usage Stats and Market Reports". Internet World Stats.

- "Accesos a Internet" (PDF) (Press release). INDEC. March 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015.

- "Argentina". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Argentina – Key Statistics, Telecom Market and Regulatory Overviews". BuddeComm.

- "Menos de la mitad de los comercios minoristas venden a través de Internet". BAE. 15 October 2014.

- "Exportación de servicios: ¿puede la Argentina ganar el Mundial?". Clarín.

- "El boom de la publicidad argentina". Ad Latina. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum.

- "Informe sobre Bancos" (PDF). BCRA.

- "Ranking del Sistema Financiero". ABA.

- "Memoria Anual 2011". ABA. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014.

- "Sin corralito, bajó el dólar y los depósitos subieron $50 millones". Clarín. 3 December 2002.

- "Estafa del Grupo Velox: 800 millones de dólares que no aparecieron más". Tiempo Argentino. 8 August 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- "The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- National Geographic Magazine. November 1939.

- "Gran número de turistas eligieron la ciudad de Mar del Plata". Hostnews.com.ar. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- Luongo, Michael. Frommer's Argentina. Wiley Publishing, 2007.

- "Evolución del Turismo Internacional" (PDF). INDEC. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2015.

- "Informe Estadístico – Año 2013" (PDF). Puerto de Buenos Aires.

- "Electricity/Heat in Argentina in 2009". IEA.

- "Potencial de energía eólica en Argentina". Asociación Argentina de Energía Eólica.

- "Argentina Heads for Solar Surge With Incentives". Bloomberg.

- Infrastructure. Argentina. National Economies Encyclopedia

- "Anuario 2007: Complementary data" (PDF). ADEFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2011.

- "Rutas: pavimentan 4.200 km y triplican red de autopistas". Secretaría de Comunicación. 3 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- "Advierten que faltan rutas para sostener el boom de los autos". La Nación.

- "Anuario 2012: Parque Automotor" (PDF). ADEFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2014.

- Ford, A. G. (1958). "Capital Exports and Growth for Argentina, 1880–1914". The Economic Journal. 68 (271): 589–593. doi:10.2307/2227581. JSTOR 2227581.

- ¿HACIA DÓNDE VA EL TREN? ESTADO Y FERROCARRIL DESPUÉS DE LAS PRIVATIZACIONES Archived 22 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine – University of Buenos Aires, 17 April 2009.

- Detalles del proyecto para conectar todos los ferrocarriles urbanos debajo del Obelisco – Buenos Aires Ciudad, 12 May 2015.

- Otro salto en la recuperación de soberanía – Pagina/12, 16 April 2015.

- Es ley la creación de Ferrocarriles Argentinos – EnElSubte, 15 April 2015.

- Ferrocarriles Argentinos: Randazzo agradeció a la oposición parlamentaria por acompañar en su recuperación Archived 16 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Sala de Prensa de la Republica Argentina, 15 April 2015.

- Boletín Oficial de Argentina N° 32.644 Archived 29 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Harán una inversión de US$ 2400 millones en el Belgrano Cargas – La Nacion, 6 December 2013.

- Sánchez, Nora (26 November 2014). "Los nuevos trenes del Mitre: asombro en los pasajeros y viajes más cómodos" [They premiered the Chinese train formations to Tigre] (in Spanish).

- "Buenos Aires commuter routes renationalised", Railway Gazette, 3 March 2015.

- "Los nuevos trenes a Mar del Plata funcionarán desde este viernes" on Telam, 19 December 2014.

- El Tren a las Nubes volvió a funcionar – InfoBAE, 5 April 2015,

- Salió de Retiro el primer tren 0km con pasajeros a Rosario – InfoBAE, 1 April 2015.

- "Empezó a circular el tren que une Posadas y Encarnación", Territorio Digital, January 2015.

- "Buenos Aires Transport Subway". Kwintessential.co.uk.

- Aumentó un 12% la cantidad de usuarios que usan el subte a diario – La Nacion, 7 May 2015.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Book of the Year (various issues): statistical appendix.

- "Más de 25 millones de pasajeros aéreos transportados en Argentina". HostelTur. 17 January 2014.

- INDEC: foreign trade

- "El 75% del rojo comercial de la industria, en cinco rubros". Clarín.

- "Licencias no Automáticas". Tiempo Argentino. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011.

- "Automotrices deberán exportar un dólar por cada dólar que importen". Tiempo Argentino. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- "Cristina presentó un proyecto para la expropiación de las acciones de YPF". Info News. 16 April 2012.

- "Repsol Deal to Open Argentine Energy Investment, Capitanich Says". Bloomberg. 23 April 2014.

- "Sector externo". Economy Ministry. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- "Argentina. Inversiones Extranjeras". Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012.

- "China-Argentina ties booming". CCTV. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- "Evolución de la Inversión Extranjera Directa en Argentina" (PDF). UNMdP. 2008.

- "Argentina, destino elegido por la inversión extranjera". Secretaría de Medios de Comunicación. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "La inversión extranjera directa en la Argentina subió 54% en 2010". Infobae.

- "Argentina recibió mayor inversión extranjera". aen. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Clarín (18 June 2008)". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- "Inversión extranjera en la Argentina: mitos y realidades". aen. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Argentina still tackling debt burden". BBC News.

- "Embargaron fondos del Central en EE.UU. y el Gobierno volvió a denunciar maniobras desestabilizadoras". clarin.com.

- Goñi, Uki (8 May 2018). "Argentina seeks IMF loan to rescue peso from downward slide". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Argentines shocked by IMF loan request". Financial Times. 9 May 2018.

- "Incidencia de la pobreza y la indigencia en 31 aglomerados urbanos Segundo semestre de 2017" (PDF) (in Spanish). Indec. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "La pobreza en la Argentina II". El Economista. 16 May 2014.

- "Porcentaje de la población con necesidades básicas insatisfechas". Secretaría de Ambiente.

- Argentina's 4Q Unemployment Rate Falls To 7.4% The Wall Street Journal

- "Caught Napping". The Economist. 21 October 2012.

- "The price of cooking the books". The Economist. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Forero, Juan. "Doctored Data Cast Doubt on Argentina: Economists Dispute Inflation Numbers". The Washington Post, 16 August 2009.

- Argentina's economy: Happy-go-lucky Cristina The Economist

- Argentina threatens inflation analysts with fine Financial Times

- "Argentine inflation data questioned even after reforms". Reuters. 7 May 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Argentine economists facing inflation fraud charge". Gulf News. Associated Press. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Argentina Quietly Hires Private Firm to Measure Inflation". PanAm Post. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Inflation, an Old Scourge, Plagues Argentina Again The New York Times

- "Inflación Verdadera". The Billion Prices Project @ MIT.

- Latin America sees uncertain 2011 BBC News

- "La mesa de los Argentinos". 7 Días. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011.

- Argentina can’t print enough pesos Financial Times

- "Índice de Precios al Consumidor Nacional urbano: base oct 2013-sep 2014=100" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Argentina Government Reports Inflation at Half of What Opposition Says". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Argentina to 'moderate' inflation at 18.6% – IMF". Buenos Aires Herald. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Argentina 2016 inflation seen at 40 percent to 42 percent: finance minister". Reuters. 24 June 2016.

- "Argentinean Supermarkets Get Hip to Inflation with Digital Price Tags". Pan Am Post. 10 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Argentina economy falling despite huge IMF support". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "The world's worst-performing currency could slip into 'crisis' mode later this year". CNBC. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "Argentina imposes currency controls". 2 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Evolución de la distribución del ingreso (EPH) Cuarto trimestre de 2017" (PDF) (in Spanish). INDEC. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Rohter, Larry (25 December 2006). "Despite recovery, inequality grows in Argentina". The New York Times.

- "La distribución del ingreso es peor". La Nación.

- "El 10% más rico acapara el 28.7% de ingresos". La Voz del Interior.

- "Income share held by highest 10%". The World Bank.

- "Table 3: Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index". 2018 Human Development Report. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Para el INDEC, solamente hay un 6,5% de pobreza". Clarín.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $3.10 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population)". World Bank. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

Notes

Further reading

- Bulmer-Thomas, Victor. The Economic History of Latin America since Independence (New York: Cambridge University Press). 2003.

- Argentina: Life After Default Article looking at how Argentina has, for the most part, recovered from its crisis in 2002

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Economy of Argentina. |

- Argentine Economy Ministry (in Spanish)

- Argentine Central Bank (in Spanish)

- Argentina's Economic Recovery: Policy Choices and Implications from the Center for Economic and Policy Research

- Comprehensive current and historical economic data

- Argentina Trade Statistics

- Argentina Export, Import, Trade Balance

- Tariffs applied by Argentina as provided by ITC's ITC Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements

- Private Inflation data from The Billion Prices Project at Massachusetts Institute of technology (in Spanish)