Theatre of ancient Rome

The architectural form of theatre in Rome has been linked to later, more well-known examples from the 1st century B.C.E. to the 3rd Century C.E.[1] The Theatre of ancient Rome referred to as a period of time in which theatrical practice and performance took place in Rome has been linked back even further to the 4th century B.C.E., following the state’s transition from monarchy to republic. [1] Theatre during this era is generally separated into genres of tragedy and comedy, which are represented by a particular style of architecture and stage play, and conveyed to an audience purely as a form of entertainment and control. [2] When it came to the audience, Romans favored entertainment and performance over tragedy and drama, displaying a more modern form of theatre that is still used in contemporary times. [2] 'Spectacle' became an essential part of an everyday Romans expectations when it came to Theatre. [1] Some works by Plautus, Terence, and Seneca the Younger that survive to this day, highlight the different aspects of Roman society and culture at the time, including advancements in Roman literature and theatre.[1]Theatre during this period of time would come to represent an important aspect of Roman society during the republican and imperial periods of Rome. [1]

Origins of Roman theatre

Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E as a monarchy under Etruscan rule, and remained as such throughout the first two and a half centuries of its existence. Following the expulsion of Rome's last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, or "Tarquin the Proud," circa 509 B.C.E., Rome became a Republic, and was henceforth led by a group of magistrates elected by the Roman people. It is believed that Roman theatre was born during the first two centuries of the Roman Republic, following the spread of Roman rule into a large area of the Italian Peninsula, circa 364 B.C.E.

Following the devastation of widespread plague in 364 B.C.E, Roman citizens began including theatrical games as a supplement to the Lectisternium ceremonies already being performed, in a stronger effort to pacify the gods. In the years following the establishment of these practices, actors began adapting these dances and games into performances by acting out texts set to music and simultaneous movement.

As the era of the Roman Republic progressed, citizens began including professionally performed drama in the eclectic offerings of the ludi (celebrations of public holidays) held throughout each year—the largest of these festivals being the Ludi Romani, held each September in honor of the Roman god Jupiter.[3] It was as a part of the Ludi Romani in 240 B.C.E. that author and playwright Livius Adronicus became the first to produce translations of Greek plays to be performed on the Roman stage.[4][5][6]

Prior to 240 B.C.E, Roman contact with northern and southern Italian cultures began to influence Roman concepts of entertainment. [7]The early Roman stage was dominated by: Phylakes(a form of tragic parody that arose in Italy during the Roman Republic from 500 to 250 B.C.E), Atellan farces (or a type of comedy that depicted the supposed backwards thinking of the southeastern Oscan town of Atella; a form of ethnic humor that arose around 300 B.C.E), and Fescennine verses (originating in southern Etruria).[7] Furthermore, Phylakes scholars have discovered vases depicting productions of Old Comedy (e.g. Aristophanes, a Greek play), leading many to ascertain that such Comedic plays were presented at one point to an Italian, if not "Latin-Speaking" audience as early as the 4th century.[7] This is supported by the fact that Latin was an essential component to Roman Theatre.[7] From 240 B.C.E to 100 B.C.E, Roman theatre had been introduced to a period of literary drama, within which classical and post-classical Greek plays had been adapted to Roman theatre.[7] From 100 B.C.E till 476 C.E, Roman entertainment began to be captured by circus-like performances, spectacles, and miming while remaining allured by theatrical performance.[7]

The early drama that emerged was very similar to the drama in Greece. Rome had engaged in a number of wars, some of which had taken place in areas of Italy, in which Greek culture had been a great influence.[8] Examples of this include the First Punic War (264-241 B.C.E) in Sicily.[8] Through this came relations between Greece and Rome, starting with the emergence of a Hellenistic world, one in which Hellenistic culture was more widely spread and through political developments via Roman conquests of Mediterranean colonies.[8] Acculturation had become specific to Greco-Roman relations, with Rome mainly adopting aspects of Greek culture, their achievements, and developing those aspects into Roman literature, art, and science.[8] Rome had become one of the first developing European cultures to shape their own culture after another.[8] With the end of the Third Macedonian War (168 B.C.E), Rome had gained greater access to a wealth of Greek art and literature, and an influx of Greek migrants, particularly Stoic philosophers such as Crates of Mallus (168 B.C.E) and even Athenian philosophers (155 B.C.E).This allowed the Romans to develop an interest in a new form of expression, philosophy.[8] The development that occurred was first initiated by playwrights that were Greeks or half-Greeks living in Rome.[8] While Greek literary tradition in drama influenced the Romans, the Romans chose to not fully adopt these traditions, and instead the dominant local language of Latin was used.[8] These Roman plays that were beginning to be performed were heavily influenced by the Etruscan traditions, particularly regarding the importance of music and performance.[8]

Genres of ancient Roman theatre

The first important works of Roman literature were the tragedies and comedies written by Livius Andronicus beginning in 240 BC. Five years later, Gnaeus Naevius, a younger contemporary of Andronicus, also began to write drama, composing in both genres as well. No plays from either writer have survived. By the beginning of the 2nd century BC, drama had become firmly established in Rome and a guild of writers (collegium poetarum) had been formed.[9]

Roman tragedy

No early Roman tragedy survives, though it was highly regarded in its day; historians know of three early tragedians—Ennius, Pacuvius and Lucius Accius. One important aspect of tragedy that differed from other genres was the implementation of choruses that were included in the action on the stage during the performances of many tragedies.[10]

From the time of the empire, however, the work of two tragedians survives—one is an unknown author, while the other is the Stoic philosopher Seneca. Nine of Seneca's tragedies survive, all of which are fabulae crepidatae (A fabula crepidata or fabula cothurnata is a Latin tragedy with Greek subjects)

Seneca appears as a character in the tragedy Octavia, the only extant example of fabula praetexta (tragedies based on Roman subjects, first created by Naevius), and as a result, the play was mistakenly attributed as having been authored by Seneca himself. However, though historians have since confirmed that the play was not one of Seneca's works, the true author remains unknown.[9]

Senecan Tragedy put forth a declamatory style, or a style of tragedy that emphasized rhetoric structures.[11] It was a style characterized through paradox, discontinuity, antithesis, and the adoption of declamatory structures and techniques that involved a aspects of compression, elaboration, epigram, and of course, hyperbole, as most of his plays seemed to emphasize such exaggerations in order to make points more persuasive.[11] Seneca wrote tragedies that reflected the soul, through which rhetoric would be used within that process of creating a tragic character and reveal something about the state of one's mind.[11] One of the most notable ways that Seneca developed a tragedy, was through the use of an aside, or a common theatre device found within Hellenistic drama, which at the time was foreign to the world of Attic tragedy.[11] Seneca explored the interior of the psychology of the mind through 'self-representational soliloquies or monologues,' which focused on one's inner thoughts, the central causes of their emotional conflicts, their self-deception, as well as other varieties of psychological turmoil that served to dramatize emotion in a way that became central to Roman tragedy, distinguishing itself from the prior used forms of Greek tragedy.[11] Those that witnessed Seneca's use of Rhetoric; pupils, readers, and audience, were noted to have been taught Seneca's use of verbal strategy, psychic mobility, and public role-play, which for many, substantially altered the mental states of many individual's.[11]

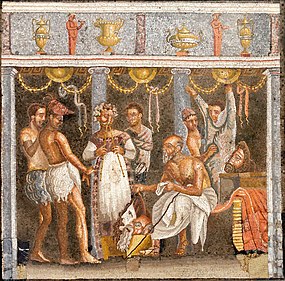

Roman comedy

All Roman comedies that have survived can be categorized as fabula palliata (comedies based on Greek subjects) and were written by two dramatists: Titus Maccius Plautus (Plautus) and Publius Terentius Afer (Terence). No fabula togata (Roman comedy in a Roman setting) has survived.

In adapting Greek plays to be performed for Roman audiences, the Roman comic dramatists made several changes to the structure of the productions. Most notable is the removal of the previously prominent role of the chorus as a means of separating the action into distinct episodes. Additionally, musical accompaniment was added as a simultaneous supplement to the plays' dialogue. The action of all scenes typically took place in the streets outside the dwelling of the main characters, and plot complications were often a result of eavesdropping by a minor character.

Plautus wrote between 205 and 184 B.C. and twenty of his comedies survive to present day, of which his farces are best known. He was admired for the wit of his dialogue and for his varied use of poetic meters. As a result of the growing popularity of Plautus' plays, as well as this new form of written comedy, scenic plays became a more prominent component in Roman festivals of the time, claiming their place in events which had previously only featured races, athletic competitions, and gladiatorial battles.

All six of the comedies that Terence composed between 166 and 160 BC have survived. The complexity of his plots, in which he routinely combined several Greek originals into one production, brought about heavy criticism, including claims that in doing so, he was ruining the original Greek plays, as well as rumors that he had received assistance from high ranking men in composing his material. In fact, these rumors prompted Terence to use the prologues in several of his plays as an opportunity to plead with audiences, asking that they lend an objective eye and ear to his material, and not be swayed by what they may have heard about his practices. This was a stark difference from the written prologues of other known playwrights of the period, who routinely utilized their prologues as a way of prefacing the plot of the play being performed.[12][9]

Stock characters in Roman comedy

The following are examples of stock characters in Roman comedy:

- The adulescens is an unmarried man, usually in late teens or twenties; his action typically surrounds the pursuit of the love of a prostitute or slave girl, who is later revealed to be a free-born woman, and therefore eligible for marriage. The adulescens character is typically accompanied by a clever slave character, who attempts to solve the adulescens’ problems or shield him from conflict.[13]

- The senex is primarily concerned with his relationship with his son, the adulescens. Although he often opposes his son's choice of love interest, he sometimes helps him to achieve his desires. He is sometimes in love with the same woman as his son, a woman who is much too young for the senex. He never gets the girl and is often dragged off by his irate wife.[13]

- The leno is the character of the pimp or 'slave dealer.' Although the activities of the character are portrayed as highly immoral and vile, the leno always acts legally and is always paid in full for his services.[13]

- The miles gloriosus is an arrogant, braggart soldier character, deriving from Greek Old Comedy. The character’s title is taken from a play of the same name written by Plautus. The miles gloriosus character is typically gullible, cowardly, and boastful.[14]

- The parasitus (parasite) is often portrayed as a selfish liar. He is typically associated with the miles gloriosus character, and hangs upon his every word. The parasitus is primarily concerned with his own appetite, or from where he will obtain his next free meal.[13]

- The matrona is the character of the wife and mother, and is usually displayed as an annoyance to her husband, constantly getting in the way of his freedom to pursue other women. After catching her husband with another woman, she typically ends the affair and forgives him. She loves her children, but is often temperamental towards her husband.[13]

- The virgo (young maiden) is an unmarried young woman, and is the love interest of the adulescens, She is often spoken of, but remains offstage. A typical plot point in the last act of the play reveals her to be of freeborn descent, and therefore eligible for marriage.[13]

Roman theatre in performance

Stage and physical space

Beginning with the first presentation of theatre in Rome in 240 B.C., plays were often presented during public festivals. Since these plays were less popular than the several other types of events (gladiatorial matches, circus events, etc.) held within the same space, theatrical events were performed using temporary wooden structures, which had to be displaced and dismantled for days at a time, whenever other spectacle events were scheduled to take place. The slow process of creating a permanent performance space was due to the staunch objection of high-ranking officials: it was the opinion of the members of the senate that citizens were spending too much time at theatrical events, and that condoning this behavior would lead to corruption of the Roman public. As a result, no permanent stone structure was constructed for the purpose of theatrical performance until 55 B.C.E.Sometimes theatre building projects could last generations before being completed, and would take a combination of private benefactors, public subscription, and proceeds from the summae honorariae or payments for office positions made by magistrates.[15] To demonstrate their benefactions, statues or inscriptions (sometimes in sums of money) were erected or inscribed for all to see in front of the tribunalia, in the proscaenium or scaenae frons, parts of the building meant to be in the public eye.[15] Building theatres required both a massive undertaking and a significant amount of time, often lasting generations.[15]

Roman theatres, particularly ones constructed in western-Roman, were mainly modeled off of Greek ones.[15] They were often arranged in a semicircle around an orchestra, but both the stage and scene building were joined together with the auditorium and were elevated to the same height, creating an enclosure very similar in structure and appearance to that of a modern theatre.[15] This was furthered by odea or smaller theatres having roofs or larger theatres having vela, allowing for the audience to have some shade.[15]

During the time of these temporary structures, theatrical performances featured a very minimalist atmosphere. This included space for spectators to stand or sit to watch the play, known as a cavea, and a stage, or scaena. The setting for each play was depicted using an elaborate backdrop (scaenae frons), and the actors performed on the stage, in the playing space in front of the scaenae frons, called the proscaenium. These structures were erected in several different places, including temples, arenas, and at times, plays were held in Rome’s central square (the forum).[12][4]

Societal divisions within the theatre were made apparent in how the auditorium was divided, typically by broad corridors or praecinctiones, into one of three zones, the ima, media, and summa cavea.[16] These zones served to section off certain groups within the population.[16] Of these three divisions, the summa cavea or 'the gallery' was where men (without togas or pullati (poor)), women, and sometimes slaves (by admission) were seated.[16] The seating arrangements of the theatre highlight the gender disparities in Roman society, as women were seated among the slaves.[16] Sur notes that it wasn’t until Augustus that segregation in the theatre was enforced, to which women had to either sit at or near the back.[16]

Theatres were paid for by certain benefactors and were seen as targets for benefaction, mainly out of the need to maintain civil order and as a consequence of the citizens desire for theatrical performance.[16] Theatres were constructed almost always through the interests of those who held the highest ranks and positions in the Roman Republic.[16] In order to maintain segregation of power, those of high rank were often seated near the front or in the public eye (tribunalia).[16] Individuals who made benefactions to the construction of theatres would often do so for propaganda reasons.[16] Whether it be at the hand of an imperial benefactor or a wealthy individual, the high cost of building a theatre usually required more than a single individual’s donations.[16]

In 55 B.C., the first permanent theatre was constructed. Built by Pompey the Great, the main purpose of this structure was actually not for the performance of drama, but rather, to allow current and future rulers a venue with which they could assemble the public and demonstrate their pomp and authority over the masses. With seating for 20,000 audience members, the grandiose structure held a 300-foot-wide stage, and boasted a three-story scaenae frons flanked with elaborate statues. The Theatre of Pompey remained in use through the early 6th century, but was dismantled for it stone in the Middle Ages. Virtually nothing of the vast structure is visible above ground today.[12][3]

Actors

The first actors that appeared in Roman performances were originally from Etruria. This tradition of foreign actors would continue in Roman dramatic performances. Beginning with early performances, actors were denied the same political and civic rights that were afforded to ordinary Roman citizens because of the low social status of actors. In addition, actors were exempt from military service, which further inhibited their rights in Roman society because it was impossible for an individual to hold a political career without having some form of military experience. While actors did not possess many rights, slaves did have the opportunity to win their freedom if they were able to prove themselves as successful actors.[17]

The open-air declaiming, gesturing, singing, and dancing of Roman stage acting required stamina and agility.[18]

The spread of dramatic performance throughout Rome occurred with the growth of acting companies that are believed to have eventually begun to travel throughout all of Italy. These acting troupes were usually composed of four to six trained actors. Usually, two to three of the actors in the troupe would have speaking roles in a performance, while the other actors in the troupe would be present on stage as attendants to the speaking actors. For the most part, actors specialized in one genre of drama and did not alternate between other genres of drama.[19]

The most famous actor to develop a career in the late Roman Republic was Quintus Roscius Gallus (125BCE- 62BCE). He was primarily known for his performances in the genre of comedy and became renowned for his performances among the elite circles of Roman society.[20] Through these connections he became intimate with Lucius Licinius Crassus, the great orator and member of the Senate, and Lucius Cornelius Sulla.[21] In addition to the acting career Gallus would build, he also would take his acting abilities and use them to teach amateur actors the craft of becoming successful in the art. He would further distinguish himself through his financial success as an actor and a teacher of acting in a field that was not highly respected. Ultimately, he chose to conclude his career as an actor without being paid for his performances because he wanted to offer his performances as a service to the Roman people.[22]

Though the possibility exists that women may have performed non-speaking roles in Roman theatrical performances, the overwhelming majority of historical evidence dictates that male actors portrayed all speaking roles. The public opinion of actors was very low, placing them within the same social status as criminals and prostitutes, and acting as a profession was considered illegitimate and repulsive. Many Roman actors were slaves, and it was not unusual for a performer to be beaten by his master as punishment for an unsatisfactory performance. These actions and opinions differ greatly from those demonstrated during the time of ancient Greek theatre, a time when actors were regarded as respected professionals, and were granted citizenship in Athens.[13][4]

Notable Roman playwrights

- Livius Andronicus, a Greek slave taken to Rome in 240 BC; wrote plays based on Greek subjects and existing plays. Rome's first playwright

- Plautus, 3rd century BC comedic playwright and author of Miles Gloriosus, Pseudolus, and Menaechmi

- Terence, wrote between 170 and 160 BC

- Titinius, writing in the second century BC

- Gaius Maecenas Melissus, 1st century playwright of a "comedy of manners"

- Seneca, 1st century dramatist most famous for Roman adaptations of ancient Greek plays (e.g. Medea and Phaedra)

- Ennius, contemporary of Plautus who wrote both comedy and tragedy

- Lucius Accius, tragic poet and literary scholar

- Pacuvius, Ennius's nephew and tragic playwright

See also

References

- Phillips, Laura Klar (2006). "The architecture of the Roman theater: Origins, canonization, and dissemination". ProQUEST. pp. 13–50. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Hammer, Dean (2010). "ROMAN SPECTACLE ENTERTAINMENTS AND THE TECHNOLOGY OF REALITY". ProQUEST. pp. 63–68. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Zarrilli, Phillip B.; McConachie, Bruce; Williams, Gary Jay; Fisher Sorgenfrei, Carol (2006). Theatre Histories: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 102, 106. ISBN 978-0-415-22728-5.

- Moore, Timothy J. (2012). Roman Theatre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521138185.

- Banham, Martin (1995). The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521434379.

- Beacham, Richard C. (1991). The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674779143.

- Phillips, Laura Klar (2006). "The architecture of the Roman theater: Origins, canonization, and dissemination". ProQUEST. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- Gesine, Manuwald (2011). Roman Republican Theatre. EBSCOhost: Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. 2011. p. 385. ISBN 9780521110167.

- Brockett, Oscar; Hildy, Franklin J. (2003). History of the Theatre. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 9780205358786.

- Gesine Manuwald, Roman Republican Theatre, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 74.

- Boyle, A. J. (1997). Tragic Seneca : An Essay in the Theatrical Tradition. Ebscohost. pp. 15–32. ISBN 1134802315. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- Bieber, Margarete (1961). The History of Greek & Roman Theater. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 151–171.

- Thorburn, John E. (2005). The Facts on File Companion to Classical Drama. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816074983.

- Hochman, Stanley (1984). McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of World Drama. VNR AG. p. 243. ISBN 9780070791695.

- Sear, Frank. "Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study". Academia: 1–83.

- Sear, Frank. "Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study". Academia: 1–83.

- Gesine Manuwald, Roman Republican Theatre, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 22-24).

- Gesine Manuwald, Roman Republican Theatre, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 73.

- Gesine Manuwald, Roman Republican Theatre, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 85.

- William J. Slater, Roman Theater and Society, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 36.

- William J. Slater, Roman Theater and Society, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 37.

- William J. Slater, Roman Theater and Society, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 41.

External links

- The Ancient Theatre Archive, Greek and Roman theatre architecture - Dr. Thomas G. Hines, Department of Theatre, Whitman College

- Cliff, U.The Roman Theatre, Clio History Journal, 2009.

- Roman Theater, Roman Colosseum, 2008.

- Classical Drama and Theatre, Mark Damen, Utah State University

- What the Roman Play Was Like, A Short History of the Drama, Martha Fletcher Bellinger

- Rhyme, Women, and Song: Getting in Tune with Plautus, Anne H. Groton, Olaf College