Julian March

The Julian March (Serbo-Croatian, Slovene: Julijska krajina) or Julian Venetia (Italian: Venezia Giulia; Venetian: Venesia Julia; Friulian: Vignesie Julie; German: Julisch Venetien) is an area of southeastern Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy and Slovenia.[1][2] The term was coined in 1863 by the Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, a native of the area, to demonstrate that the Austrian Littoral, Veneto, Friuli and Trentino (then all part of the Austrian Empire) shared a common Italian linguistic identity. Ascoli emphasized the Augustan partition of Roman Italy at the beginning of the Empire, when Venetia et Histria was Regio X (the Tenth Region).[2][3][4]

Julian March | |

|---|---|

Region | |

House on the Italy–Slovenia border in Gorizia with the 1945–1947 inscription "This is Yugoslavia" | |

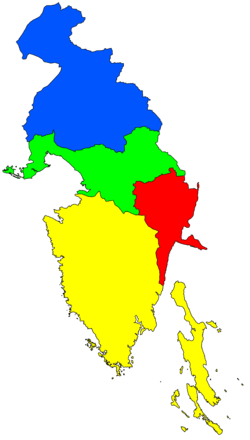

The Julian March within the Kingdom of Italy (1923-1947), with its four provinces: Gorizia (blue), Trieste (green), Carnaro (red), Pola (yellow). |

The term was later endorsed by Italian irredentists, who sought to annex regions in which ethnic Italians made up most (or a substantial portion) of the population: the Austrian Littoral, Trentino, Fiume and Dalmatia. The Triple Entente promised the regions to Italy in the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in exchange for Italy's joining the Allied Powers in World War I. The secret 1915 Treaty of London promised Italy territories largely inhabited by Italians (such as Trentino) in addition to those largely inhabited by Croats or Slovenes; the territories housed 421,444 Italians, and about 327,000 ethnic Slovenes.[5][6]

A contemporary Italian autonomous region, bordering on Slovenia, is named Friuli-Venezia Giulia ("Friuli and Julian Venetia").[7]

Etymology

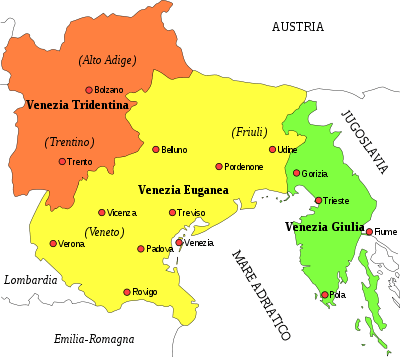

The term "Julian March" is a partial translation of the Italian name "Venezia Giulia" (or "Julian Venetia"), coined by the Italian Jewish historical linguist Graziadio Ascoli, who was born in Gorizia. In an 1863 newspaper article,[4] Ascoli focused on a wide geographical area north and east of Venice which was under Austrian rule; he called it Triveneto ("the three Venetian regions"). Ascoli divided Triveneto into three parts:

- Euganean Venetia (Venezia Euganea or Venezia propria; Venetia in the strict sense), made up of Italy's Veneto region and most of the territory of Friuli (roughly corresponding to the present Italian provinces of Udine and Pordenone)

- Tridentine Venetia (Venezia Tridentina): the present Italian region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

- Julian Venetia (Venezia Giulia): "Gorizia, Trieste and Istria ... including the land between the Venetia in the strict sense of the term, the Julian Alps, and the sea"[4]

According to this definition, Triveneto overlaps the ancient Roman region of Regio X - Venetia et Histria introduced by Emperor Augustus in his administrative reorganization of Italy at the beginning of the first century AD. Ascoli (who was born in Gorizia) coined his terms for linguistic and cultural reasons, saying that the languages spoken in the three areas were substantially similar. His goal was to stress to the ruling Austrian Empire the region's[8] Latin and Venetian roots and the importance of the Italian linguistic element.[4]

The term "Venezia Giulia" did not catch on immediately, and began to be used widely only in the first decade of the 20th century.[4] It was used in official administrative acts by the Italian government in 1922–1923 and after 1946, when it was included in the name of the new region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

History

Early Middle Ages to the Republic of Venice

At the end of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Migration Period, the area had linguistic boundaries between speakers of Latin (and its dialects) and the German- and Slavic-language speakers who were moving into the region. German tribes first arrived in present-day Austria and its surrounding areas between the fourth and sixth centuries. They were followed by the Slavs, who appeared on the borders of the Byzantine Empire around the sixth century and settled in the Eastern Alps between the sixth and eighth centuries. In Byzantine Dalmatia, on the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, several city-states had limited autonomy. The Slavs retained their languages in the interior, and local Romance languages (followed by Venetian and Italian) continued to be spoken on the coast.[9]

Beginning in the early Middle Ages, two main political powers shaped the region: the Republic of Venice and the Habsburg (the dukes and, later, archdukes of Austria). During the 11th century, Venice began building an overseas empire (Stato da Màr) to establish and protect its commercial routes in the Adriatic and southeastern Mediterranean Seas. Coastal areas of Istria and Dalmazia were key parts of these routes[lower-alpha 1] since Pietro II Orseolo, the Doge of Venice, established Venetian rule in the high and middle Adriatic around 1000.[10]. The Venetian presence was concentrated on the coast, replacing Byzantine rule and confirming the political and linguistic separation between coast and interior. The Republic of Venice began expanding toward the Italian interior (Stato da Tera) in 1420,[10], acquiring the Patriarchate of Aquileia (which included a portion of modern Friuli—the present-day provinces of Pordenone and Udine—and part of internal Istria).

The Habsburg held the March of Carniola, roughly corresponding to the central Carniolan region of present-day Slovenia (part of their holdings in Inner Austria), since 1335. During the next two centuries, they gained control of the Istrian cities of Pazin and Rijeka-Fiume, the port of Trieste (with Duino), Gradisca and Gorizia (with its county in Friuli).

Republic of Venice to 1918

The region was relatively stable from the 16th century to the 1797 fall of the Republic of Venice, which was marked by the Treaty of Campo Formio between Austria and France. The Habsburgs gained Venetian lands on the Istrian Peninsula and the Quarnero (Kvarner) islands, expanded their holdings in 1813 with Napoleon's defeats and the dissolution of the French Illyrian provinces. Austria gained most of the republic's territories, including the Adriatic coast, Istria and portions of present-day Croatia (such as the city of Karlstadt).

Habsburg rule abolished political borders which had divided the area for almost 1,000 years. The territories were initially assigned to the new Kingdom of Illyria, which became the Austrian Littoral in 1849. This was established as a crown land (Kronland) of the Austrian Empire, consisting of three regions: the Istrian peninsula, Gorizia and Gradisca, and the city of Trieste.[11]

The Italian-Austrian war of 1866, followed by the passage of what was then known as Veneto (the current Veneto and Friuli regions, except for the province of Gorizia) to Italy, did not directly affect the Littoral; however, a small community of Slavic speakers in northeastern Friuli (an area known as Slavia friulana - Beneška Slovenija) became part of the Kingdom of Italy. Otherwise, the Littoral lasted until the end of the Austrian Empire in 1918.

Kingdom of Italy (1918–1943)

The Kingdom of Italy annexed the region after World War I according to the Treaty of London and later Treaty of Rapallo, including the County of Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste, Istria, the current Italian municipalities of Tarvisio, Pontebba and Malborghetto Valbruna, and partially and fully Slovene portions of the former Austrian Littoral. Exceptions were the island of Krk and the municipality of Kastav, which became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.[12] Rijeka-Fiume became a city-state, the Free State of Fiume, before it was abolished in 1924 and divided between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

The new provinces of Gorizia (which was merged with the Province of Udine between 1924 and 1927), Trieste, Pola and Fiume (after 1924) were created. Italians lived primarily in cities and along the coast, and Slavs inhabited the interior. Fascist persecution, "centralising, oppressive and dedicated to the forcible Italianisation of the minorities",[13] caused the emigration of about 105,000[6] Slovenes and Croats from the Julian March—around 70,000 to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and 30,000 to Argentina. Several thousand Dalmatian Italians moved from Yugoslavia to Italy after 1918, many to Istria and Trieste.

In response to the Fascist Italianization of Slovene areas, the militant anti-Fascist organization TIGR emerged in 1927. TIGR co-ordinated Slovene resistance against Fascist Italy until it was dismantled by the secret police in 1941, and some former members joined the Yugoslav Partisans. The Slovene Partisans emerged that year in the occupied Province of Ljubljana, and spread by 1942 to the other Slovene areas which had been annexed by Kingdom of Italy twenty years earlier.

German occupation and resistance (1943–1945)

After the Italian armistice of September 1943, many local uprisings took place. The town of Gorizia was temporarily liberated by partisans, and a liberated zone in the Upper Soča Valley known as the Kobarid Republic lasted from September to November 1943. The German Army began to occupy the region and encountered severe resistance from Yugoslav partisans, particularly in the lower Vipava Valley and the Alps. Most of the lowlands were occupied by the winter of 1943, but Yugoslav resistance remained active throughout the region and withdrew to the mountains.

In the aftermath of the fall 1943 Italian armistice, the first of what became known as the Foibe massacres occurred (primarily in present-day Croatian Istria). The Germans established the Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral, officially part of the Italian Social Republic but under de facto German administration, that year. Many areas, (especially north and north-east of Gorizia) were controlled by the partisan resistance, which was also active on the Karst Plateau and interior Istria. The Nazis tried to repress the Yugoslav guerrillas with reprisals against the civilian population; entire villages were burned down, and thousands of people were interned in Nazi concentration camps. However, the Yugoslav resistance took over most of the region by the spring of 1945.

Italian resistance in the operational zone was active in Friuli and weaker in the Julian March, where it was confined to intelligence and underground resistance in the larger towns (especially Trieste and Pula). In May 1945, the Yugoslav Army entered Trieste; over the following days, virtually the entire Julian March was occupied by Yugoslav forces. Retaliation against real (and potential) political opponents occurred, primarily to the Italian population.

Contested region (1945–1954)

The Western allies adopted the term "Julian March" as the name for the territories which were contested between Italy and the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1945 and 1947. The Morgan Line was drawn in June 1945, dividing the region into two militarily administered zones. Zone B was under Yugoslav administration and excluded the cities of Pula, Gorizia, Trieste, the Soča Valley and most of the Karst Plateau, which were under joint British-American administration. During this period, many Italians left the Yugoslav-occupied area.

In 1946, U.S. President Harry S. Truman ordered an increase in U.S. troops in their occupation zone (Zone A) and the reinforcement of air forces in northern Italy after Yugoslav forces shot down two U.S. Army transport planes.[14] An agreement on the border was chosen from four proposed solutions[15] at the Paris Peace Conference that year. Yugoslavia acquired the northern part of the region east of Gorizia, most of Istria and the city of Fiume. A Free Territory of Trieste was created, divided into two zones—one under Allied and the other under Yugoslav military administration. Tensions continued, and in 1954 the territory was abolished and divided between Italy (which received the city of Trieste and its surroundings) and Yugoslavia.[16]

Since 1954

In Slovenia the Julian March is known as the Slovene Littoral, encompassing the regions of Goriška and Slovenian Istria and (sometimes) the Slovene-speaking areas of the provinces of Gorizia and Trieste. In Croatia, the traditional name of Istria is used. After the divisions of 1947 and 1954, the term "Julian March" survived in the name of the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region of Italy.

Ethnolinguistic structure

Two major ethnolinguistic clusters were unified in the region. The western portion was inhabited primarily by Italians (Italian, Venetian and Friulian were the three major languages), with a small Istriot-speaking minority. The eastern and northern areas were inhabited by South Slavs (Slovenes and Croats), with small Montenegrin (Peroj) and Serb minorities.

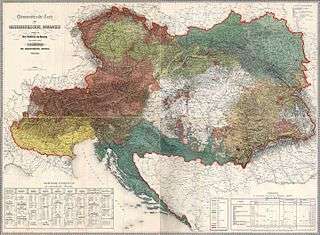

Other ethnic groups included Istro-Romanians in eastern Istria, Carinthian Germans in the Canale Valley and smaller German- and Hungarian-speaking communities in larger urban centres, primarily members of the former Austro-Hungarian elite. This is illustrated by the 1855 ethnographic map of the Austrian Empire compiled by Karl von Czoernig-Czernhausen and issued by the Austrian k. u. k. department of statistics. According to the 1910–1911 Austrian census, the Austrian Littoral (which would be annexed by Italy from 1920 to 1924) had a population of 978,385. Italian was the everyday language (Umgangsprache) of 421,444 people (43.1 percent); 327,230 (33.4 percent) spoke Slovene, and 152,500 (15.6 percent) spoke Croatian.[17] About 30,000 people (3.1 percent) spoke German, 3,000 (0.3 percent) spoke Hungarian, and small clusters of Istro-Romanian and Czech speakers existed. The Friulian, Venetian and Istriot languages were considered Italian; an estimated 60,000 or more "Italian" speakers (about 14 percent) spoke Friulian.[18]

Romance languages

The standard Italian language was common among educated people in Trieste, Gorizia, Istria and Fiume/Rijeka. In Trieste (and to a lesser extent in Istria), Italian was the predominant language in primary education. The Italian-speaking elite dominated the governments of Trieste and Istria under Austro-Hungarian rule, although they were increasingly challenged by Slovene and Croatian political movements. Before 1918, Trieste was the only self-governing Austro-Hungarian unit in which Italian speakers were the majority of the population.

Most of the Romance-speaking population did not speak standard Italian as their native language, but two other closely related Romance languages: Friulian and Venetian.[19] There was no attempt to introduce Venetian into education and administration.

Friulian was spoken in the south-western lowlands of the county of Gorizia and Gradisca (except for the Monfalcone-Grado area, where Venetian was spoken), and in the town of Gorizia. Larger Friulian-speaking centres included Cormons, Cervignano, and Gradisca d'Isonzo. A dialect of Friulian (Tergestine) was spoken in Trieste and Muggia, evolving into a Venetian dialect during the 18th century. According to contemporary estimates, three-quarters of the Italians in the county of Gorizia and Gradisca were native Friulian speakers—one-quarter of the county's population, and seven to eight percent of the population of the Julian March.

Venetian dialects were concentrated in Trieste, Rijeka and Istria, and the Istro-Venetian dialect was the predominant language of the west Istrian coast. In many small west Istrian towns, such as Koper (Capodistria), Piran (Pirano) or Poreč (Parenzo), the Venetian-speaking majority reached 90 percent of the population and 100 percent in Umag (Umago) and Muggia. Venetian was also a strong presence on Istria's Cres-Lošinj archipelago and in the peninsula's eastern and interior towns such as Motovun, Labin, Plomin and, to a lesser extent, Buzet and Pazin. Although Istro-Venetian was strongest in urban areas, clusters of Venetian-speaking peasants also existed. This was especially true for the area around Buje and Grožnjan in north-central Istria, where Venetian spread during the mid-19th century (often in the form of a Venetian-Croat pidgin). In the county of Gorizia and Gradisca, Venetian was spoken in the area around Monfalcone and Ronchi (between the lower Isonzo River and the Karst Plateau) in an area popularly known as Bisiacaria and in the town of Grado. In Trieste the local Venetian dialect (known as Triestine) was widely spoken, although it was the native language of only about half the city's population. In Rijeka-Fiume, a form of Venetian known as Fiumano emerged during the late 18th and early 19th centuries and became the native language of about half the city's population.

In addition to these two large language groups, two smaller Romance communities existed in Istria. In the south-west, on the coastal strip between Pula and Rovinj, the archaic Istriot language was spoken. In some villages of eastern Istria, north of Labin, the Istro-Romanian language was spoken by about 3,000 people.

South Slavic languages

Slovene was spoken in the north-eastern and southern parts of Gorizia and Gradisca (by about 60 percent of the population), in northern Istria and in the Inner Carniolan areas annexed by Italy in 1920 (Postojna, Vipava, Ilirska Bistrica and Idrija). It was also the primary language of one-fourth to one-third of the population of Trieste. Smaller Slovene-speaking communities lived in the Canale Valley (Carinthian Slovenes), in Rijeka and in larger towns outside the Slovene Lands (especially Pula, Monfalcone, Gradisca d'Isonzo and Cormons). Slavia Friulana - Beneška Slovenija, the community living since the eighth century in small towns (such as Resia) in the valleys of the Natisone, Torre and Judrio Rivers in Friuli, has been part of Italy since 1866.

A variety of Slovene dialects were spoken throughout the region. The Slovene linguistic community in the Julian March was divided into as many as 11 dialects (seven larger and four smaller dialects), belonging to three of the seven dialect groups into which Slovene is divided. Most Slovenes were fluent in standard Slovene, with the exception of some northern Istrian villages (where primary education was in Italian and the Slovene national movement penetrated only in the late 19th century) and the Carinthian Slovenes in the Canale Valley, who were Germanised until 1918 and frequently spoke only the local dialect.

Slovene-Italian bilingualism was present only in some north-west Istrian coastal villages and the confined semi-urban areas around Gorizia and Trieste, while the vast majority of Slovene speakers had little (or no) knowledge of Italian; German was the predominant second language of the Slovene rural population.

Croatian was spoken in the central and eastern Istrian peninsula, on the Cres-Lošinj archipelago; it was the second-most-spoken language (after Venetian) in the town of Rijeka. The Kajkavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian was spoken around Buzet in north-central Istria; Čakavian was predominant in all other areas, frequently with strong Kajkavian and Venetian vocabulary influences. Italian-Croatian bilingualism was frequent in western Istria, on the Cres-Lošinj archipelago and in Rijeka, but rare elsewhere.

Linguistic minorities

German was the predominant language in secondary and higher education throughout the region until 1918, and the educated elite were fluent in German. Many Austrian civil servants used German in daily life, especially in larger urban centres. Most of the German speakers would speak Italian, Slovene or Croatian on social and public occasions, depending on their political and ethnic preferences and location. Among the rural population, German was spoken by about 6,000 people in the Canale Valley. In the major urban areas (primarily Trieste and Rijeka), Hungarian, Serbian, Czech and Greek were spoken by smaller communities.

See also

- Austrian Riviera

- Dalmatia

- History of Trieste

- Venetian Slovenia

- Operation Unthinkable

Notes

- Adriatic routes to and from Venice were based on Dalmatian and Istrian harbours, which were more easily accessible for vessels than their Italian counterparts.

References

- The New Europe by Bernard Newman, pp. 307, 309

- Contemporary History on Trial: Europe Since 1989 and the Role of the Expert Historian by Harriet Jones, Kjell Ostberg, Nico Randeraad ISBN 0-7190-7417-7 p. 155

- Bernard Newman, The New Europe, pp. 307, 309

- Marina Cattaruzza, Italy and Its Eastern Border, 1866–2016, Routledge 2016 - ch. I ISBN 978-1138791749

- Lipušček, U. (2012) Sacro egoismo: Slovenci v krempljih tajnega londonskega pakta 1915, Cankarjeva založba, Ljubljana. ISBN 978-961-231-871-0

- Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004) "Clash of civilisations", Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol.12, No.2, p.4

- "The History of "Venetia Julia" Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- In 1863 all of the Triveneto, as defined by Ascoli, was part of the Austrian Empire. After the Italian third war of independence against Austria of 1866, Veneto and part of Friuli (i. e. Venezia Euganea in Ascoli's terms) were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy.

- Jože Pirjevec, Serbi croati sloveni, Il Mulino, 2002, ISBN 978-88-15-08824-6

- F. C. Lane, Venice. A maritime Republic, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973

- Veneto, including western part of modern Friuli, which had also become part of Austrian Empire since 1815, was included in the Kingdom of Lombardo-Veneto

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2007-11-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Problem of Trieste and the Italo-Yugoslav Border by Glenda Sluga, p. 47

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-09. Retrieved 2008-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Italo-Yugoslav Border Issue: Four Solutions And The Urgent Need For Just One

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2008-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jože Pirjevec and Milica Kacin Wohinz (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 2000), p. 303.

- Rolf Wörsdörfer, Krisenherd Adria 1915–1955: Konstruktion und Artikulation des Nationalen im italienisch-jugoslawischen Grenzraum (Paderborn : F. Schöningh, 2004).

- It should be understood that Italian language's division among regional dialects has always been very pronounced. Due to the lack of a central Italian state, a standard Italian language did not actually exist until the second half of the 19th century, nor there was, until then, an agreement among scholars on this language's features. As a result, only 2.5% of Italy's population could speak the Italian standardized language properly when the nation was unified in 1861. See for example the Italian language historic evolution and M. Paul Lewis, ed. (2009). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16th ed.). Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

External links

- The Problem of Trieste and the Italo-Yugoslav Border by Glenda Sluga

- Istituto Giuliano: an Italian association dedicated to the promotion of culture and tradition in the Julian March

- Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli Venezia Giulia: an Italian association dedicated to the study of the history of resistance war in Friuli and Julian March