Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (Italian: Partito Socialista Italiano, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy,[4] whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, the PSI dominated the Italian left until after World War II, when it was eclipsed in status by the Italian Communist Party. The Socialists came to special prominence in the 1980s, when their leader Bettino Craxi, who had severed the residual ties with the Soviet Union and re-branded the party as "liberal-socialist",[5][6][7] served as Prime Minister (1983–1987). The PSI was disbanded in 1994 as a result of the Tangentopoli scandals.[8]

The party has had a series of legal successors: the Italian Socialists (1994–1998), the Italian Democratic Socialists (1998–2007) and the Italian Socialist Party (since 2007, originally "Socialist Party"). These parties have never reached the popularity of the old PSI. Socialist leading members and voters have joined quite different parties, from the centre-right Forza Italia, The People of Freedom, and the 2013 Forza Italia, to the centre-left Democratic Party.[9]

Prior to World War I, future dictator Benito Mussolini was a member of the PSI.[10]

History

Early years

The Italian Socialist Party was founded in 1892 as the Party of Italian Workers (Partito dei Lavoratori Italiani) by delegates of several workers' associations and parties, notably including the Italian Workers' Party and the Milanese Socialist League.[11] It was part of a wave of new socialist parties at the end of the 19th century and had to endure persecution by the Italian government during its early years. While in Sicily the Fasci Siciliani were spreading, the party was celebrating on September 8, 1893 its second congress in Reggio Emilia and changed its name to Socialist Party of Italian Workers (Partito Socialista dei Lavoratori Italiani). During the third congress on January 13, 1895 in Parma it decided to adopt the name of Italian Socialist Party and Filippo Turati was elected its secretary.

At the start of the 20th century, the PSI chose not to strongly oppose the governments led by five-time Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti. This conciliation with the existing governments and its improving electoral fortunes helped to establish the PSI as a mainstream Italian political party by the 1910s.

Despite the party's improving electoral results, the PSI remained divided into two major branches, the Reformists and the Maximalists. The Reformists, led by Filippo Turati, were strong mostly in the unions and the parliamentary group. The Maximalists, led by Costantino Lazzari, were affiliated with the London Bureau of socialist groups, an international association of left-wing socialist parties.

In 1912, the Maximalists led by Benito Mussolini prevailed at the party convention and this led to the split of the Italian Reformist Socialist Party. In 1914 the party obtained good success in local elections, especially in the industrialized northern Italy, and Mussolini became leader of the City Council of Milan. From 1912 to 1914, Mussolini headed up the Bolshevik wing of the Italian Socialist Party who purged moderate or reformist socialists.[12]

Rise of fascism

World War I tore the party apart. The orthodox socialists were challenged by advocates of national syndicalism, who called for revolutionary war to liberate Italian-speaking territories from authoritarian Austrian control and force the government by threat of violence to create a corporatist state. The national syndicalists intended to support Italian republicans in overthrowing the monarchy if such reforms were not made and if Italy did not enter the war together with the Allied Powers and their struggle against the Central Empires, seen as the final fight for the worldwide triumph of freedom and democracy. The dominant internationalist and pacifist wing of the party remained committed to avoiding what it called a "bourgeois war". The PSI's refusal to support the war led to its national syndicalist faction either leaving or being purged from the party, such as Mussolini who had begun to show sympathy to the national syndicalist cause. A number of the national syndicalists expelled from the PSI later joined Mussolini's Fascist Revolutionary movement in 1914, including the Fasces of Revolutionary Action in 1915 (later Italian Fasces of Combat). In late 1921, during the Third Fascist Congress, Mussolini turned the Fasces of Combat into the National Fascist Party.[13]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the PSI quickly aligned itself in support of the Communist Bolshevik movement in Russia and supported its call for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie. In the 1919 general election, the PSI reached its highest result ever: 32.0% and 156 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. From 1919 to the 1920s, the Socialists and the Fascists emerged as prominent rival movements in Italy's urban centres, often resorting to political violence in their clashes. In 1919, the Socialist Party of Turin formed the Red Army of Turin, which was accompanied by a proposal to organise a national confederation of Red Scouts and Cyclists.[14] The left-wing of the party broke away in 1921 to form the Communist Party of Italy, a division from which the PSI never recovered and which had enormous consequences on Italian politics. In 1922, another split occurred when the reformist wing of the party, headed by Turati and Giacomo Matteotti, was expelled and formed the Unitary Socialist Party (PSU).

In 1924, Matteotti was assassinated by Fascists and shortly afterwards a fascist dictatorship was established in Italy. In 1926, the PSI and all other political parties except the Fascist Party were banned. The party's leadership remained in exile during the Fascist years and in 1930 the PSU was re-integrated into the PSI. The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1930 and 1940.[15]

Post-World War II

In the 1946 general election and the first after World War II, the PSI obtained 20.7% of the vote, narrowly ahead of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) that gained 18.9%. In the 1948 general election, the US secretly convinced the British Labour Party to pressure social democrats to end all coalitions with communists, which fostered a split in PSI [16]—Socialists led by Pietro Nenni chose to take part in the Popular Democratic Front along with the PCI, while social democrat Giuseppe Saragat launched the Italian Workers' Socialist Party. The PSI was weakened by the split and was far less organized than the PCI; therefore, Communist candidates were far more competitive. As a result, the Socialist parliamentary delegation was cut by a half. Nonetheless, the PSI continued its alliance with the PCI until 1956, when Soviet repression in Hungary caused a major split between the two parties.

Starting from 1963, the Socialists participated in the centre-left governments in alliance with Christian Democracy (DC), the Italian Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) and the Italian Republican Party (PRI). These governments acceded to many of the demands of the PSI for social reform and laid the foundations for Italy's modern welfare state.[17] During the 1960s and 1970s, the PSI lost much of its influence despite actively participating in the government. The PCI gradually outnumbered it as the dominant political force in the Italian left. The PSI tried to enlarge its base by joining forces with the PSDI under the name Unified Socialist Party (PSU). However, after a dismaying loss in the 1968 general election in which the PSU gained far fewer seats in total than each of the two parties had obtained separately in 1963, it disbanded. The 1972 general election underlined the PSI's precipitate decline as the party received less than 10% of the vote compared to 14.2% in 1958.

Bettino Craxi

In 1976, Bettino Craxi was elected new secretary of the party. From the beginning, Craxi tried to undermine the PCI which until then had been continuously increasing its votes in elections and to consolidate the PSI as a modern, strongly pro-European reformist social-democratic party, with deep roots in the democratic left-wing. This strategy called for ending most of the party's historical traditions as a working-class trade union based party and attempting to gain new support among white-collar and public sector employees. At the same time, the PSI increased its presence in the big state-owned enterprises and became heavily involved in corruption and illegal party funding which would eventually result in the mani pulite investigations.

Even if the PSI never became a serious electoral challenger either to the PCI or the DC, its pivotal position in the political arena allowed it to claim the post of Prime Minister for Craxi after the 1983 general election. The electoral support for the Christian Democrats was significantly weakened, leaving it with 32.9% of the vote, compared to the 38.3% it gained in 1979. The PSI that had obtained only 11% threatened to leave the parliamentary majority unless Craxi was made Prime Minister. The Christian Democrats accepted this compromise to avoid a new election. Craxi became the first Socialist in the history of the Italian Republic to be appointed Prime Minister.

Unlike many of its predecessors, Craxi's government proved to be durable, lasting three-and-a-half years from 1983 to 1987. During those years, the PSI gained popularity as Craxi successfully boosted the country's GNP and controlled inflation. He demonstrated Italy's independence and nationalism during the clash with the United States during the Sigonella incident. Moreover, Craxi spoke of many reforms, including the transformation of Italian Constitution toward a presidential system. The PSI looked like the driving force behind the bulk of reforms initiated by the Pentapartito, but Craxi lost his post in March 1987 due to a conflict with the other parties of the coalition over the proposed budget for 1987.

In the 1987 general election, the PSI won 14.3% of the vote and this time it was the Christian Democrats' turn to govern. From 1987 to 1992, the PSI participated in four governments, allowing Giulio Andreotti to take power in 1989 and to govern until 1992. The Socialists held a strong balance of power, which made them more powerful than the Christian Democrats, who had to depend on it to form a majority in Parliament. The PSI kept tight control of this advantage.

The alternative which Craxi had wanted so much was taking shape, namely the idea of a "Social Unity" with the other left-wing political parties, including the PCI, proposed by Craxi in 1989 after the fall of Communism. He believed that the collapse of communism in eastern Europe had undermined the PCI and made Social Unity inevitable. In fact, the PSI was in line to become the Italy's second largest party and to become the dominant force of a new left-wing coalition opposed to a Christian Democrat-led one, but this did not actually happen because of the rise of the Northern League and the Tangentopoli scandals.

Decline

In February 1992, Mario Chiesa, a Socialist hospital administrator in Milan, was caught taking a bribe. Craxi denounced Chiesa by calling him an isolated thief, who had nothing to do with the party as a whole. Feeling betrayed, Chiesa confessed his crimes to the police and implicated others, starting a chain reaction of judicial investigations that would ultimately engulf the entire political system. The investigations, named mani pulite ("clean hands") was carried out by three Milanese magistrates among whom Antonio Di Pietro quickly stood out becoming a national hero thanks to his charismatic character and his ability to extract confessions.

The investigations were suspended for four weeks in order for the 1992 Italian general election to take place in an uninfluenced atmosphere and the PSI managed to garner 13.6% of the vote in spite of the corruption scandals. Many in the party thought the scandal had been brought under control, but they failed to realize that investigations would eventually be launched against ministers and party leaders. Furthermore, as early as May 1992 public opinion unconditionally supported the magistrates against a political system that the majority of Italians already distrusted. Craxi himself was under criminal investigation since December 1992. In April 1993, the Parliament denied four times the authorization for magistrates to continue investigation for Craxi. Italian newspapers shouted scandal and Craxi was besieged at his Rome residence by a crowd of young people, who threw coins at him, shouting: "Bettino, do you want these as well?". This scene was to become one of the many symbols of that period.

In 1992–1993, many Socialist regional, provincial and municipal deputies, MPs, mayors and even ministers found themselves overwhelmed with accusations and arrests. At this point, public opinion turned against the Socialists and many regional headquarters of the PSI were besieged by people who wanted an honest party with true socialist values. Between January 1993 and February 1993, Claudio Martelli (former Justice Minister and Deputy Prime Minister) started to contend for party leadership. Martelli stepped forward as a candidate, emphasizing the need to clean the party of corruption and make it electable. Although he had many supporters, Martelli and Craxi were both caught in a scandal dating back to 1982, when the Banco Ambrosiano gave to the two of them around 7 million dollars. Martelli subsequently resigned from the party and from the government. Giuliano Amato, a Socialist, resigned as Prime Minister in April 1993. His government was succeeded by a technocratic government led by Carlo Azeglio Ciampi.

Dissolution

Craxi resigned as party secretary in February 1993. Between 1992 and 1993, most members of the party left politics and three Socialist deputies committed suicide. Craxi was succeeded by two Socialist trade-unionists, first Giorgio Benvenuto and then by Ottaviano Del Turco. In the December 1993 provincial and municipal elections, the PSI was virtually wiped out, receiving around 3% of the vote. In Milan, where the PSI had won 20% in 1990, the PSI received a mere 2% and was shut out of the council. Del Turco tried in vain to regain credibility for the party.

By the 1994 general election, the PSI was in a state of near-collapse. Its remains contested the election as part of the Alliance of Progressives dominated by the post-Communist incarnation of the PCI, the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS). Del Turco had quickly changed the party symbol to reinforce the idea of innovation. However, this did not stop the PSI gaining only 2.2% of the votes compared to 13.6% in 1992. The PSI elected 16 deputies[18] and 14 senators,[19] down from 92 deputies and 49 senators of 1992. Most of them came from the left-wing of the party as Del Turco himself did. Most Socialists joined other political forces, mainly Forza Italia, the new party led by Silvio Berlusconi, the Patto Segni and Democratic Alliance.

The party was disbanded on 13 November 1994 after two years of agony in which almost all of its longtime leaders, especially Bettino Craxi, were involved in Tangentopoli and decided to leave politics. The 100-year-old party closed down, partially thanks to its leaders for their personalization of the PSI.

Diaspora

The Socialists who did not align with the other parties organized themselves in two groups: the Italian Socialists (SI) of Enrico Boselli, Ottaviano Del Turco, Roberto Villetti, Riccardo Nencini, Cesare Marini and Maria Rosaria Manieri, who decided to be autonomous from the PDS; and the Labour Federation (FL) of Valdo Spini, Antonio Ruberti, Giorgio Ruffolo, Giuseppe Pericu, Carlo Carli and Rosario Olivo, who entered in close alliance with it. The SI eventually merged with other Socialist splinter groups to form the Italian Democratic Socialists (SDI) in 1998 while the FL merged with PDS to form the Democrats of the Left (DS) later on that year.

Between 1994 and 1996, many former Socialists joined Forza Italia as did Giulio Tremonti, Franco Frattini, Massimo Baldini and Luigi Cesaro. Gianni De Michelis, Ugo Intini and several politicians close to Bettino Craxi formed the Socialist Party while others like Fabrizio Cicchitto and Enrico Manca launched the Reformist Socialist Party. In the 2000s, two outfits claimed to be the party's successor, namely the Italian Democratic Socialists (SDI) that evolved from the Italian Socialists (SI) and the New Italian Socialist Party (NPSI) founded by Gianni De Michelis, Claudio Martelli and Bobo Craxi in 2001.

However, both the SDI and the NPSI were minor political forces. A number of Socialist members and voters joined the centre-right Forza Italia[20] while others joined the DS and Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy (DL). Many others were not members of any party any more.[21] Some former Socialists are still affiliated to The People of Freedom (PdL) while others are in centre-left Democratic Party (PD) and modern-day Socialist Party (PS).[22] The Socialists who joined Forza Italia include Giulio Tremonti, Franco Frattini, Fabrizio Cicchitto, Renato Brunetta, Amalia Sartori, Francesco Musotto, Margherita Boniver, Francesco Colucci, Raffaele Iannuzzi, Maurizio Sacconi, Luigi Cesaro and Stefania Craxi. Although it may seem unusual for self-identified socialists to be members of a centre-right party, many of those who did so felt that the centre-left was now dominated by former Communists and the best way to fight for mainstream social democracy was through FI/PdL. Valdo Spini, Giorgio Benvenuto, Gianni Pittella and Guglielmo Epifani joined the DS and Enrico Manca, Tiziano Treu, Laura Fincato and Linda Lanzillotta joined DL. Giuliano Amato joined The Olive Tree as an independent.

In 2007, some former Socialists, including the SDI, a portion of the NPSI led by Gianni De Michelis, The Italian Socialists of Bobo Craxi, Socialism is Freedom of Rino Formica and splinters from the DS joined forces and formed the Socialist Party (PS), renamed Italian Socialist Party (PSI) in 2011. Nowadays, the PSI is the only Italian party represented in Parliament which explicitly refers to itself as Socialist, even though many other Socialist associations and organization participate to the political debate both in the centre-right and the centre-left.

Popular support

When the Socialists came out in the late 1890s, they were present only in rural Emilia-Romagna and southern Lombardy, where they won their first seats of the Chamber of Deputies, but they soon enlarged their base in other areas of the country, especially the urban areas around Turin, Milan, Genoa and to some extent Naples, densely populated by industrial workers. In the 1900 general election, the party won 5.0% of the vote and 33 seats, its best result so far. Emilia-Romagna was confirmed as the Socialist heartland (20.2% and 13 seats), but the party did very well also in Piedmont and Lombardy.[23]

By the end of the 1910s, the Socialists had broadened their organization to all the regions of Italy, but they were obviously stronger in the North, where they emerged earlier and where they had their constituency. In the 1919 general election, thanks to the electoral reforms of the previous decade and especially the introduction of proportional representation in place of the old first-past-the-post system, they had their best result ever: 32.0% and 156 seats. The PSI was at the time the representative of both the rural workers of Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and north-western Piedmont and the industrial workers of Turin, Milan, Venice, Bologna and Florence. In 1919,the party won 49.7% in Piedmont (over 60% in Novara), 45.9% in Lombardy (over 60% in Mantua and Pavia), 60.0% in Emilia-Romagna (over 70% around Bologna and Ferrara), 41.7% in Tuscany and 46.5% in Umbria.[23]

In the 1921 general election and after the split of the Communist Party of Italy, the PSI was reduced to 24.5% and was particularly damaged in Piedmont and Tuscany, where the Communists got more than 10% of the vote.[23] During the Italian Resistance, which was fought mostly in Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna and Central Italy, the Communists were able to take roots and organize people much better than the Socialists so that at the end of World War II the balance between the two parties was completely changed. In the 1946 general election, the PSI was narrowly ahead of the Communists (20.7% over 18.7%), but it was no longer the dominant party in Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany.[24]

In the 1948 general election, the Socialists took part to the Popular Democratic Front with the Italian Communist Party (PCI), but they lost almost half of their seats in the Chamber of Deputies due to the better get-out-the-vote machine of the Communists and the split of the social-democratic faction from the party, the Italian Workers' Socialist Party (7.1%, with peaks over 10% in the Socialist strongholds of the North). In 1953, the PSI was reduced to 12.7% of the vote and to its heartlands above the Po River, having gained more votes than the Communists only narrowly in Lombardy and Veneto. The margin between the two parties would have become larger and larger until its peak in 1976, when the PCI won 34.4% of the vote and the PSI stopped at 9.6%. At that time, the Communists had almost five times the vote of the Socialists in the PSI's ancient heartlands of rural Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany and three times in the Northern regions, where the PSI had some local strongholds left such as in north-eastern Piedmont, north-western and southern Lombardy, north-eastern Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia, where it gained steadily 12–20% of the vote.[23][25]

Under the leadership of Bettino Craxi in the 1980s, the PSI had a substantial increase in term of votes. The party strengthened its position in Lombardy, north-eastern Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and broadened its power base to Southern Italy as all the other parties of Pentapartito coalition (Christian Democrats, Republicans, Democratic Socialists and Liberals) were experiencing. In the 1987 general election, the PSI gained good result with 14.3% of the vote, but below expectations after four years of government led by Craxi. Alongside the high shares of vote in north-western Lombardy and the North-East (both around 18–20%), the PSI did fairly well in Campania (14.9%), Apulia (15.3%), Calabria (16.9%) and Sicily (14.9%). In 1992, this trend toward the South was even more evident—while the Socialists, like the Communists and the Christian Democrats, had lost votes to Lega Nord especially in Lombardy, they gained in the South, reaching 19.6% of the vote in Campania, 17.8% in Apulia and 17.2% in Calabria.[23][25] This is why the PSI's main successors, the Italian Socialists, the Italian Democratic Socialists, the New Italian Socialist Party and the modern-day Italian Socialist Party, had always been stronger in those Southern regions.

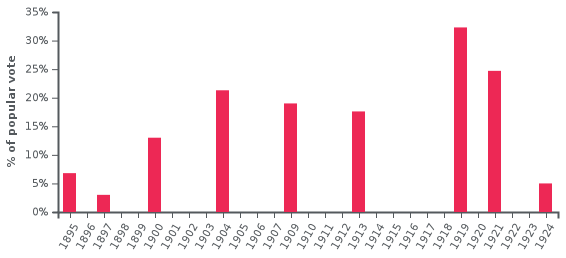

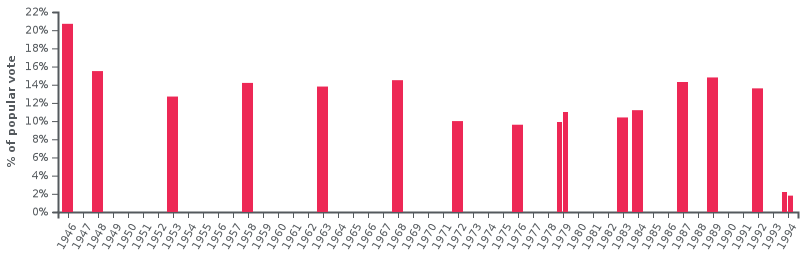

The electoral results of the PSI in general (Chamber of Deputies) and European Parliament elections since 1895 are shown in the chart below.

- Kingdom of Italy

- Italian Republic

Electoral results

Italian Parliament

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895 | 82,523 (4th) | 6.8 | 15 / 508 |

||

| 1897 | 82,536 (5th) | 3.0 | 15 / 508 |

||

| 1900 | 164,946 (3rd) | 13.0 | 33 / 508 |

||

| 1904 | 326,016 (2nd) | 21.3 | 29 / 508 |

||

| 1909 | 347,615 (2nd) | 19.0 | 41 / 508 |

||

| 1913 | 883,409 (2nd) | 17.6 | 52 / 508 |

||

| 1919 | 1,834,792 (1st) | 32.3 | 156 / 508 |

||

| 1921 | 1,631,435 (1st) | 24.7 | 123 / 535 |

||

| 1924 | 360,694 (4th) | 5.0 | 22 / 535 |

||

| 1929 | Banned | – | 0 / 400 |

||

| 1934 | Banned | – | 0 / 400 |

||

| 1946 | 4,758,129 (2nd) | 20.7 | 115 / 556 |

||

| 1948 | 8,136,637 (2nd)[lower-alpha 1] | 31.0 | 53 / 574 |

||

| 1953 | 3,441,014 (3rd) | 12.7 | 75 / 590 |

||

| 1958 | 4,206,726 (3rd) | 14.2 | 84 / 596 |

||

| 1963 | 4,255,836 (3rd) | 13.8 | 83 / 630 |

||

| 1968 | 4,605,832 (3rd)[lower-alpha 2] | 14.5 | 62 / 630 |

||

| 1972 | 3,210,427 (3rd) | 10.0 | 61 / 630 |

||

| 1976 | 3,542,998 (3rd) | 9.6 | 57 / 630 |

||

| 1979 | 3,630,052 (3rd) | 9.9 | 62 / 630 |

||

| 1983 | 4,223,362 (3rd) | 11.4 | 73 / 630 |

||

| 1987 | 5,505,690 (3rd) | 14.3 | 94 / 630 |

||

| 1992 | 5,343,808 (3rd) | 13.6 | 92 / 630 |

||

| 1994 | 849,429 (10th) | 2.2 | 15 / 630 |

||

| Senate of the Republic | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 6,969,122 (2nd)[lower-alpha 1] | 30.8 | 41 / 237 |

||

| 1953 | 2,891,605 (3rd) | 11.9 | 26 / 237 |

||

| 1958 | 3,682,945 (3rd) | 14.1 | 36 / 246 |

||

| 1963 | 3,849,495 (3rd) | 14.0 | 44 / 315 |

||

| 1968 | 4,354,906 (3rd)[lower-alpha 2] | 15.2 | 36 / 315 |

||

| 1972 | 3,225,707 (3rd) | 10.7 | 33 / 315 |

||

| 1976 | 3,208,164 (3rd) | 10.2 | 30 / 315 |

||

| 1979 | 3,252,410 (3rd) | 10.4 | 32 / 315 |

||

| 1983 | 3,539,593 (3rd) | 11.4 | 38 / 315 |

||

| 1987 | 3,535,457 (3rd) | 10.9 | 43 / 315 |

||

| 1992 | 4,523,873 (3rd) | 13.6 | 49 / 315 |

||

| 1994 | 103,490 (11th) | 0.3 | 9 / 315 |

||

- Into the Popular Democratic Front.

- Into the Unified PSI-PSDI.

European Parliament

| European Parliament | |||||

| Election year | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 3,866,946 (3rd) | 11.0 | 9 / 81 |

||

| 1984 | 3,940,445 (3rd) | 11.2 | 9 / 81 |

||

| 1989 | 5,151,929 (3rd) | 14.8 | 12 / 81 |

||

| 1994 | 606,538 (10th) | 1.8 | 2 / 87 |

||

Leadership

- Secretary: Pietro Nenni (1931–1945), Sandro Pertini (1945–1946), Ivan Matteo Lombardo (1946–1947), Lelio Basso (1947–1948), Alberto Jacometti (1948–1949), Pietro Nenni (1949–1963), Francesco De Martino (1963–1968), Mauro Ferri (1968–1969), Francesco De Martino (1969–1970), Giacomo Mancini (1970–1972), Francesco De Martino (1972–1976), Bettino Craxi (1976–1993), Giorgio Benvenuto (1993), Ottaviano Del Turco (1993–1994)

- Party Leader in the Chamber of Deputies: Paolo De Michelis (1946–1947), Pietro Nenni (1947–1964), Mauro Ferri (1964–1968), Flavio Orlandi (1968–1969), Antonio Giolitti (1969–1970), Luigi Bertoldi (1970–1973), Luigi Mariotti (1973–1976), Bettino Craxi (1976), Vincenzo Balzamo (1976–1980), Silvano Labriola (1980–1983), Rino Formica (1983–1986), Lelio Lagorio (1986–1987), Gianni De Michelis (1987–1988), Nicola Capria (1988–1991), Salvatore Andò (1991–1992), Giuseppe La Ganga (1992–1993), Nicola Capria (1993–1994)

Symbols

The PSI was rather unusual among mainstream socialist/social-democratic parties in Europe in using the hammer and sickle as its symbol. However, the symbolism of the party was gradually moderated. In 1978 Craxi decided to change the party logo of the party. He chose a red carnation to represent the new course of the party, in honour of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. The party shrank the size of the old hammer and sickle in the lower part of the symbol. It was eventually eliminated altogether in 1987.

.svg.png) 1919–1921

1919–1921 1921–1943

1921–1943 1944-1947

1944-1947.svg.png) 1947–1966

1947–1966.svg.png) 1987–1991

1987–1991

Further reading

- Gundle, Stephen (1996). The rise and fall of Craxi's Socialist Party. The New Italian Republic: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to Berlusconi. Routledge. pp. 85–98.

References

- Luciano Bardi; Piero Ignazi (1998). "The Italian Party System: The Effective Magnitude of an Earthquake". In Piero Ignazi; Colette Ysmal (eds.). The Organization of Political Parties in Southern Europe. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-275-95612-7.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Frederic Spotts; Theodor Wieser (30 April 1986). Italy: A Difficult Democracy: A Survey of Italian Politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 68, 80. ISBN 978-0-521-31511-1. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- James C. Docherty; Peter Lamb (2006). Jon Woronoff (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Socialism. Scarecrow Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8108-6477-1. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "17 novembre 2003 – "Il PSI di Craxi visto dal PCI di Berliguer" intevento di Umberto Ranieri al Convegno di Italianieuropei "Riformismo socialista e Italia repubblicana. Storia e politica – Il Socialista". ilsocialista.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Il socialismo liberale di Craxi". Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Il primo riformista italiano". ilfoglio.it. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- DeLisa, Antonio (11 October 2012). "Mani Pulite e Tangentopoli". STORIOGRAFIA - HISTORIOGRAPHY - HISTORIOGRAPHIE (in Italian). Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Ancona, Pietro. "IL PARTITO SOCIALISTA ITALIANO VERSO IL DECLINO E LA DIASPORA". www.luccifanti.it. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Anthony James Gregor (1979). Young Mussolini and the Intellectual Origins of Fascism. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520037991.

- "Italian Socialist Party". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, Dennis Mack (1983). Mussolini. New York City, NY. Vintage Books. p. 96

- Delzell, Charles F. (1971). Mediterranean Fascism, 1919-1945. Harper & Row. p. 26. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "The Red Army of Turin" (25 October 1919). Workers' Dreadnought. Vol. VI. No. 31. p. 1122.

- Kowalski, Werner (1985). Geschichte der sozialistis chen arbeiter-internationale: 1923 – 19. Berlin. Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften.

- Pedaliu, E. (2003-10-23). Britain, Italy and the Origins of the Cold War. Springer. ISBN 9780230597402.

- Stille, Alexander (1996). Excellent Cadavers: The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic.

- They were Giuseppe Albertini, Enrico Boselli, Carlo Carli, Ottaviano Del Turco, Fabio Di Capua, Vittorio Emiliani, Mario Gatto, Luigi Giacco, Gino Giugni, Alberto La Volpe, Vincenzo Mattina, Valerio Mignone, Rosario Olivo, Corrado Paoloni, Giuseppe Pericu and Valdo Spini.

- They were Paolo Bagnoli, Orietta Baldelli, Francesco Barra, Luigi Biscardi, Guido De Martino, Gianni Fardin, Carlo Gubbini, Maria Rosaria Manieri, Cesare Marini, Maria Antonia Modolo, Michele Sellitti, Giancarlo Tapparo, Antonino Valletta and Antonio Vozzi.

- "«Temeva di essere ucciso con un caffè in cella»". Archived 6 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Archiviostorico.corriere.it. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- In the XV Legislature (2006–2008), 70 out of 1060 Italian MPs and MEPs came from the Italian Socialist Party: 38 were affiliated to Forza Italia (Roberto Antonione, Valentina Aprea, Simone Baldelli, Massimo Baldini, Paolo Bonaiuti, Margherita Boniver, Anna Bonfrisco, Renato Brunetta, Francesco Brusco, Giulio Camber, Giampiero Cantoni, Luigi Cesaro, Fabrizio Cicchitto, Ombretta Colli, Francesco Colucci, Stefania Craxi, Gaetano Fasolino, Antonio Gentile, Paolo Guzzanti, Raffaele Iannuzzi, Vanni Lenna, Antonio Leone, Chiara Moroni, Francesco Musotto, Emiddio Novi, Gaetano Pecorella, Marcello Pera, Mauro Pili, Sergio Pizzolante, Guido Podestà, Gaetano Quagliariello, Maurizio Sacconi, Jole Santelli, Amalia Sartori, Aldo Scarabosio, Giorgio Stracquadanio, Renzo Tondo and Giulio Tremonti), 9 to the Italian Democratic Socialists (Rapisardo Antinucci, Enrico Boselli, Enrico Buemi, Giovanni Crema, Lello Di Gioia, Pia Elda Locatelli, Giacomo Mancini Jr., Angelo Piazza and Roberto Villetti), 8 to the Democrats of the Left (Giorgio Benvenuto, Antonello Cabras, Carlo Fontana, Beatrice Magnolfi, Gianni Pittella, Valdo Spini, Rosa Villecco and Sergio Zavoli), 5 to Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy (Laura Fincato, Linda Lanzillotta, Maria Leddi, Pierluigi Mantini and Tiziano Treu), 4 to the New Italian Socialist Party (Alessandro Battilocchio, Lucio Barani, Mauro Del Bue and Gianni De Michelis), 2 to the Movement for Autonomy (Pietro Reina and Giuseppe Saro), 1 to Italy of Values (Aurelio Misiti), 1 to the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats (Giuseppe Drago) and 2 non-party members (Giuliano Amato and Giovanni Ricevuto)

- In the XVI Legislature (2008–2013), 65 out of 1060 Italian MPs and MEPs come from the Italian Socialist Party: 44 are affiliated to The People of Freedom (Roberto Antonione, Valentina Aprea, Simone Baldelli, Massimo Baldini, Lucio Barani, Luca Barbareschi, Paolo Bonaiuti, Anna Bonfrisco, Margherita Boniver, Renato Brunetta, Stefano Caldoro, Giulio Camber, Gianpiero Cantoni, Giuliano Cazzola, Luigi Cesaro, Fabrizio Cicchitto, Ombretta Colli, Francesco Colucci, Stefania Craxi, Diana De Feo, Sergio De Gregorio, Franco Frattini, Antonio Gentile, Lella Golfo, Paolo Guzzanti, Giancarlo Lehner, Antonio Leone, Innocenzo Leontini, Chiara Moroni, Fiamma Nirenstein, Gaetano Pecorella, Marcello Pera, Mauro Pili, Sergio Pizzolante, Guido Podestà, Gaetano Quagliariello, Maurizio Sacconi, Jole Santelli, Giuseppe Saro, Amalia Sartori, Umberto Scapagnini, Aldo Scarabosio, Giorgio Straquadanio and Giulio Tremonti), 12 to the Democratic Party (Antonello Cabras, Franca Donaggio, Linda Lanzillotta, Maria Leddi, Pierluigi Mantini, Alberto Maritati, Gianni Pittella, Francesco Tempestini, Tiziano Treu, Umberto Veronesi, Rosa Villecco and Sergio Zavoli), 4 to the Socialist Party (Rapisardo Antonucci, Alessandro Battilocchio, Gianni De Michelis and Pia Elda Locatelli), 2 to the Movement for Autonomy (Elio Vittorio Belcastro and Luciano Sardelli), 2 to Italy of Values (Francesco Barbato and Aurelio Misiti) and 1 to the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats (Giuseppe Drago).

- Corbetta, Piergiorgio Corbetta and Piretti, Maria Serena (2009). Atlante storico-elettorale d'Italia. Zanichelli. Bologna.

- "Dipartimento per gli Affari Interni e Territoriali". Archived 25 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "::: Ministero dell'Interno ::: Archivio Storico delle Elezioni". Elezionistorico.interno.it. Retrieved 24 August 2013.