Isle of Man

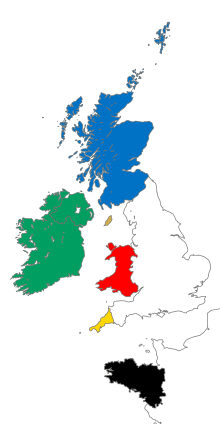

The Isle of Man (Manx: Mannin [ˈmanɪnʲ], also Ellan Vannin [ˈɛlʲan ˈvanɪnʲ]), also known as Mann /mæn/, is a self-governing British Crown dependency situated in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Ireland. The head of state, Queen Elizabeth II, holds the title of Lord of Mann and is represented by a lieutenant governor. The United Kingdom has responsibility for the island's military defence.

Isle of Man Mannin, Ellan Vannin (Manx) | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): "Quocunque Jeceris Stabit" (Latin) (English: "Wherever you throw it, it shall stand") | |

| Anthem: "O Land of Our Birth" "God Save the Queen" | |

Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe (dark grey) | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Norse control | 9th century |

| Scottish control | 2 July 1266 |

| English control | 1399 |

| Revested into British Crown | 10 May 1765 |

| Capital and largest city | Douglas 54°09′N 4°29′W |

| Official languages | English Manx |

| Religion | Largely Christian |

| Demonym(s) | Manx (Manxman (plural: Manxmen), Manxwoman (plural: Manxwomen)) |

| Government | Parliamentary democratic constitutional monarchy |

| Elizabeth II | |

| Sir Richard Gozney | |

| Howard Quayle | |

| Legislature | Tynwald |

| Legislative Council | |

| House of Keys | |

| Area | |

• Total | 572 km2 (221 sq mi) (unranked) |

• Water (%) | 1 |

| Highest elevation | 2,030 ft (620 m) |

| Population | |

• 2016 census | 83,314[1] (202nd) |

• Density | 148/km2 (383.3/sq mi) (78th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $7.43 billion (161st) |

• Per capita | $84,600 (9th) |

| Gini | 0.41[2] low |

| HDI (2010) | 0.849[3] very high · 14th |

| Currency | Pound sterling Manx pound (£) (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

| UTC+01:00 (BST) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Mains electricity | 240 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

| UK postcode | |

| ISO 3166 code | IM |

| Internet TLD | .im |

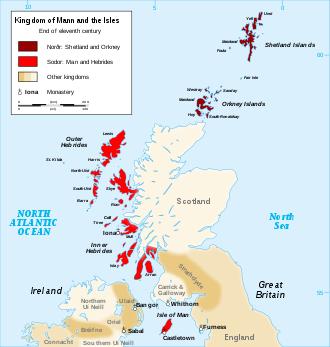

Humans have lived on the island since before 6500 BC. Gaelic cultural influence began in the 5th century AD, and the Manx language, a branch of the Goidelic languages, emerged. In 627 King Edwin of Northumbria conquered the Isle of Man along with most of Mercia. In the 9th century Norsemen established the thalassocratic Kingdom of the Isles, which included the Isle of Man. Magnus III, King of Norway from 1093 to 1103, reigned also as King of Mann and the Isles between 1099 and 1103.[4]

In 1266 the island became part of Scotland under the Treaty of Perth, after being ruled by Norway. After a period of alternating rule by the kings of Scotland and England, the island came under the feudal lordship of the English Crown in 1399. The lordship revested into the British Crown in 1765, but the island never became part of the 18th-century kingdom of Great Britain, nor of its successors, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the present-day United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It has always retained its internal self-government.

In 1881 the Isle of Man parliament, Tynwald, became the first national legislative body in the world to give women the right to vote in a general election, although this excluded married women.[5][6] In 2016, UNESCO awarded the Isle of Man biosphere reserve status.[7]

Insurance and online gambling each generate 17% of the GNP, followed by information and communications technology and banking with 9% each.[8] Internationally, the Isle of Man is known for the Isle of Man TT (Tourist Trophy) motorcycle races[9] and for the Manx cat, a breed of cat with short or no tails.[10] The inhabitants (Manx) are considered a Celtic nation.[11]

Name

The Manx name of the Isle of Man is Ellan Vannin: ellan (Manx pronunciation: [ɛlʲan]) is a Manx word meaning "island"; Mannin (IPA: [manɪnʲ]) appears in the genitive case as Vannin (IPA: [vanɪnʲ]), with initial consonant mutation, hence Ellan Vannin, "Island of Mann". The short form used in English is spelled either Mann or Man. The earliest recorded Manx form of the name is Manu or Mana.[12]

The Old Irish form of the name is Manau or Mano. Old Welsh records named it as Manaw, also reflected in Manaw Gododdin, the name for an ancient district in north Britain along the lower Firth of Forth.[13] The oldest known reference to the island calls it Mona, in Latin (Julius Caesar, 54 BC); in the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder records it as Monapia or Monabia, and Ptolemy (2nd century) as Monœda (Mοναοιδα, Monaoida) or Mοναρινα (Monarina), in Koine Greek. Later Latin references have Mevania or Mænavia (Orosius, 416),[14] and Eubonia or Eumonia by Irish writers. It is found in the Sagas of Icelanders as Mön.[15]

The name is probably cognate with the Welsh name of the island of Anglesey, Ynys Môn,[13] usually derived from a Celtic word for 'mountain' (reflected in Welsh mynydd, Breton menez, and Scottish Gaelic monadh),[16][17] from a Proto-Celtic *moniyos.

The name was at least secondarily associated with that of Manannán mac Lir in Irish mythology (corresponding to Welsh Manawydan fab Llŷr).[18] In the earliest Irish mythological texts, Manannán is a king of the otherworld, but the 9th-century Sanas Cormaic identifies a euhemerised Manannán as "a famous merchant who resided in, and gave name to, the Isle of Man".[19] Later, a Manannán is recorded as the first king of Mann in a Manx poem (dated 1504).[20]

History

The island was cut off from the surrounding islands around 8000 BC as sea levels rose following the end of the ice age. Humans colonised it by travelling by sea some time before 6500 BC.[21] The first occupants were hunter-gatherers and fishermen. Examples of their tools are kept at the Manx Museum.[22]

The Neolithic Period marked the beginning of farming, and the people began to build megalithic monuments, such as Cashtal yn Ard near Maughold, King Orry's Grave at Laxey, Meayll Circle near Cregneash, and Ballaharra Stones at St John's. There were also the local Ronaldsway and Bann cultures.[23]

During the Bronze Age, the size of burial mounds decreased. The people put bodies into stone-lined graves with ornamental containers. The Bronze Age burial mounds survived as long-lasting markers around the countryside.[24]

The ancient Romans knew of the island and called it Insula Manavia.[25] Scholars have not determined whether they conquered the island.

Around the 5th century AD, large-scale migration from Ireland precipitated a process of Gaelicisation, evidenced by Ogham inscriptions, and the Manx language developed. It is a Goidelic language closely related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic.[26]

Vikings arrived at the end of the 8th century. They established Tynwald and introduced many land divisions that still exist. In 1266 King Magnus VI of Norway ceded the islands to Scotland in the Treaty of Perth. But Scotland's rule over Mann did not become firmly established until 1275, when the Manx were defeated in the Battle of Ronaldsway, near Castletown.

In 1290 King Edward I of England sent Walter de Huntercombe to take possession of Mann. It remained in English hands until 1313, when Robert Bruce took it after besieging Castle Rushen for five weeks. In 1314, it was retaken for the English by John Bacach of Argyll. In 1317, it was retaken for the Scots by Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray and Lord of the Isle of Man. It was held by the Scots until 1333. For some years thereafter control passed back and forth between the kingdoms until the English took it for the final time in 1346.[27] The English Crown delegated its rule of the island to a series of lords and magnates. Tynwald passed laws concerning the government of the island in all respects and had control over its finances, but was subject to the approval of the Lord of Mann.

In 1866, the Isle of Man obtained limited home rule, with partly democratic elections to the House of Keys, but the Legislative Council was appointed by the Crown. Since then, democratic government has been gradually extended.

The Isle of Man has designated more than 250 historic sites as registered buildings.

Geography

The Isle of Man is located in the middle of the northern Irish Sea, almost equidistant from England to the east, Northern Ireland to the west, and Scotland (closest) to the north; while Wales to the south is almost the distance of the Republic of Ireland to the southwest. It is 52 kilometres (32 mi) long and, at its widest point, 22 kilometres (14 mi) wide. It has an area of around 572 square kilometres (221 sq mi).[28] Besides the island of Mann itself, the political unit of the Isle of Man includes some nearby small islands: the seasonally inhabited Calf of Man,[29] Chicken Rock on which stands an unmanned lighthouse, St Patrick's Isle and St Michael's Isle. The last two of these are connected to the main island by permanent roads/causeways.

Ranges of hills in the north and south are separated by a central valley. The northern plain, by contrast, is relatively flat, consisting mainly of deposits from glacial advances from western Scotland during colder times. There are more recently deposited shingle beaches at the northernmost point, the Point of Ayre. The island has one mountain higher than 600 metres (2,000 ft), Snaefell, with a height of 620 metres (2,034 ft).[28] According to an old saying, from the summit one can see six kingdoms: those of Mann, Scotland, England, Ireland, Wales, and Heaven.[30][31] Some versions add a seventh kingdom, that of the sea, or Neptune.[32]

Population

At the 2016 census,[1] the Isle of Man was home to 83,314 people, of whom 26,997 resided in the island's capital, Douglas, and 9,128 in the adjoining village of Onchan. The population decreased by 1.4% between the 2011 and 2016 censuses. By country of birth, those born in the Isle of Man were the largest group (49.8%), while those born in the United Kingdom were the next largest group at 40% (33.9% in England, 3% in Scotland, 2% in Northern Ireland and 1.1% in Wales), 1.8% in the Republic of Ireland and 0.75% in the Channel Islands. The remaining 8.5% were born elsewhere in the world, with 5% coming from EU countries (other than Ireland).

Census

The Isle of Man Full Census, last held in 2016,[1] has been a decennial occurrence since 1821, with interim censuses being introduced from 1966. It is separate from, but similar to, the Census in the United Kingdom.

The 2001 census was conducted by the Economic Affairs Division of the Isle of Man Treasury, under the authority of the Census Act 1929.

Government

The United Kingdom is responsible for the island's defence and ultimately for good governance, and for representing the island in international forums, while the island's own parliament and government have competence over all domestic matters.[33]

Socio-political structure

The island's parliament, Tynwald, is claimed to have been in continuous existence since 979 or earlier, purportedly making it the oldest continuously governing body in the world, though evidence supports a much later date.[34] Tynwald is a bicameral or tricameral legislature, comprising the House of Keys (directly elected by universal suffrage with a voting age of 16 years) and the Legislative Council (consisting of indirectly elected and ex-officio members). These two bodies also meet together in joint session as Tynwald Court.

The executive branch of government is the Council of Ministers, which is composed of members of the House of Keys. It is headed by the Chief Minister, currently (2019) Howard Quayle MHK.

Vice-regal functions of the head of state are performed by a lieutenant governor.

External relations and security

In various laws of the United Kingdom, "the United Kingdom" is defined to exclude the Isle of Man. Historically, the UK has taken care of its external and defence affairs, and retains paramount power to legislate for the Island. However, in 2007, the Isle of Man and the UK signed an agreement[35] that established frameworks for the development of the international identity of the Isle of Man. There is no separate Manx citizenship. Citizenship is covered by UK law, and Manx people are classed as British citizens. The Isle of Man holds neither membership nor associate membership of the European Union, and lies outside the European Economic Area (EEA). There is a long history of relations and cultural exchange between the Isle of Man and Ireland. The Isle of Man's historic Manx language (and its modern revived variant) are closely related to both Scottish Gaelic and the Irish language, and in 1947, Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera spearheaded efforts to save the dying Manx language.

Defence

Under British law, the Isle of Man is not part of the United Kingdom. However, the UK takes care of its external and defence affairs.[36] There are no independent military forces on the Isle of Man, although HMS Ramsey is affiliated with the town of the same name.[37] From 1938 to 1955 there was the Manx Regiment of the British Territorial Army, which saw extensive action during the Second World War.[38] In 1779, the Manx Fencible Corps, a fencible regiment of three companies, was raised; it was disbanded in 1783 at the end of the American War of Independence. Later, the Royal Manx Fencibles was raised at the time of the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. The 1st Battalion (of 3 companies) was raised in 1793. A 2nd Battalion (of 10 companies) was raised in 1795,[39] and it saw action during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The regiment was disbanded in 1802.[40] A third body of Manx Fencibles was raised in 1803 to defend the island during the Napoleonic Wars and to assist the Revenue. It was disbanded in 1811.[41] In 2015 a multi-capability recruiting and training unit of the British Army Reserve was established in Douglas.[42]

Manxman status

There is no citizenship of the Isle of Man as such under the British Nationality Acts 1948 and 1981.

The Passport Office, Isle of Man, Douglas, accepts and processes applications for the Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Man, who is formally responsible for issuing Isle of Man–issued British passports, entitled "British Islands – Isle of Man".

British citizens who have 'Manxman status', not being either born, naturalised or registered in the United Kingdom, and without a parent or grandparent who has, or if they have not themselves personally been resident in the United Kingdom for more than five consecutive years, do not have the same rights as other British citizens with regard to employment and establishment in other parts of the EU (other than the UK and Ireland).[43]

Isle of Man-issued British passports can presently be issued to any British citizen resident in the Isle of Man, and also to British citizens who have a qualifying close personal connection to the Isle of Man but are now resident either in the UK or in either one of the two other Crown Dependencies.

European Union

The Isle of Man was never part of the European Union, nor did it have a special status, and thus it did not take part in the 2016 referendum on the UK's EU membership.[44] However, Protocol 3 of the UK's Act of Accession to the Treaty of Rome included the Isle of Man within the EU's customs area, allowing for trade in Manx goods without tariffs throughout the EU.[45] As it is not part of the EU's internal market, there are still limitations on the movement of capital, services and labour.

EU citizens are entitled to travel and reside, but not work, in the island without restriction. British citizens with Manxman status are under the same circumstances and restrictions as any other non-EU European relating country to work in the EU.[46][47]

The political and diplomatic impacts of Brexit on the island are still uncertain. The UK has confirmed that the Crown Dependencies' positions were included in the Brexit negotiations.[48] The Brexit withdrawal agreement explicitly includes the Isle of Man in its territorial scope, but makes no other mention of it.[49] The island's government website states that after the end of the implementation period, the Isle of Man's relationship with the EU will depend on the agreement reached between the UK and the EU on their future relationship.[50]

Commonwealth of Nations

The Isle of Man is not itself a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. By virtue of its relationship with the United Kingdom, it takes part in several Commonwealth institutions, including the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association and the Commonwealth Games. The Government of the Isle of Man has made calls for a more integrated relationship with the Commonwealth,[51] including more direct representation and enhanced participation in Commonwealth organisations and meetings, including Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings.[52] The Chief Minister of the Isle of Man has said: "A closer connection with the Commonwealth itself would be a welcome further development of the island's international relationships."[53]

Politics

Most Manx politicians stand for election as independents rather than as representatives of political parties. Although political parties do exist, their influence is not nearly as strong as in the United Kingdom.

There are three political parties in the Isle of Man:

- The Liberal Vannin Party (established 2006) has two seats in the House of Keys; it promotes greater Manx autonomy and more accountability in government.

- The Manx Labour Party is active, and for much of the 20th century had several MHKs, but currently has no seats in either branch of Tynwald.

- The Isle of Man Green Party was established in 2016, but currently only has representation at local government level.[54]

A number of pressure groups also exist on the island. Mec Vannin advocate the establishment of a sovereign republic.[55] The Positive Action Group campaign for three key elements to be introduced into the governance of the island: open accountable government, rigorous control of public finances, and a fairer society.[56]

Local government

Local government on the Isle of Man is based partly on the island's 17 ancient parishes. There are two types of local authorities:

- a corporation for the Borough of Douglas, and bodies of commissioners for the town districts of Castletown, Peel and Ramsey, and

- the village districts of Kirk Michael, Onchan, Port Erin and Port St Mary, and the 14 "parish districts" (those parishes or parts of parishes which do not fall within the districts previously mentioned). Each of these districts also has its own body of commissioners.

Local authorities are under the supervision of the Isle of Man Government's Department of Local Government and the Environment (DOLGE).

Public services

Education

Public education is under the Department of Education, Sport & Culture. Thirty-two primary schools, five secondary schools and the University College Isle of Man function under the department.[57]

Health

Health and social care on the Isle of Man is the responsibility of the Department of Health and Social Care. Healthcare is free for residents and visitors from the UK.[58]

Emergency services

The Isle of Man Government maintains five emergency services.[59] These are:

- Isle of Man Constabulary (police)

- Isle of Man Coastguard

- Isle of Man Fire and Rescue Service

- Isle of Man Ambulance Service

- Isle of Man Civil Defence Corps

All of these services are controlled directly by the Department of Home Affairs of the Isle of Man Government, and are independent of the United Kingdom. Nonetheless, the Isle of Man Constabulary voluntarily submits to inspection by the British inspectorate of police,[60] and the Isle of Man Coastguard contracts Her Majesty's Coastguard (UK) for air-sea rescue operations.

Crematorium

The island's sole crematorium is in Glencrutchery Road, Douglas and is operated by Douglas Borough Council. Usually staffed by four, in March 2020 an increase of staff to 12 was announced by the council leader, responding to the threat of coronavirus which could require more staff.[61]

Economy

The Isle of Man Department for Enterprise manages the diversified economy in 12 key sectors.[62] The largest sectors by GNP are insurance and eGaming with 17% of GNP each, followed by ICT and banking with 9% each. The 2016 census lists 41,636 total employed.[1] The largest sectors by employment are "medical and health", "financial and business services", construction, retail and public administration.[63] Manufacturing, focused on aerospace and the food and drink industry,[64] employs almost 2000 workers and contributes about 5% of gross domestic product (GDP). The sector provides laser optics, industrial diamonds, electronics, plastics and aerospace precision engineering. Tourism, agriculture, fishing, once the mainstays of the economy, now make very little contributions to the island's GDP.

After 30 years of continued GDP growth, the unemployment rate is just around 1%.

The Isle of Man is a low-tax economy with no capital gains tax, wealth tax, stamp duty, or inheritance tax[65] and a top rate of income tax of 20%.[66] A tax cap is in force: the maximum amount of tax payable by an individual is £200,000 or £400,000 for couples if they choose to have their incomes jointly assessed. Personal income is assessed and taxed on a total worldwide income basis rather than a remittance basis. This means that all income earned throughout the world is assessable for Manx tax rather than only income earned in or brought into the island.

The standard rate of corporation tax for residents and non-residents is 0%. Retail business profits above £500,000 and banking business income are taxed at 10%, and rental (or other) income from land and buildings situated on the Isle of Man is taxed at 20%.[67]

Trade takes place mostly with the United Kingdom. The island is in customs union with the UK, and related revenues are pooled and shared under the Common Purse Agreement. This means that the Isle of Man cannot have the lower excise revenues on alcohol and other goods that are enjoyed in the Channel Islands.

The Manx government promotes island locations for making films by offering financial support. Since 1995, over 100 films have been made on the island.[68] Most recently the island has taken a much wider strategy to attract the general digital media industry in film, television, video and eSports.[69]

The Isle of Man Government Lottery operated from 1986 to 1997. Since 2 December 1999 the island has participated in the United Kingdom National Lottery.[70][71] The island is the only jurisdiction outside the United Kingdom where it is possible to play the UK National Lottery.[72] Since 2010 it has also been possible for projects in the Isle of Man to receive national lottery Good Causes Funding.[73][74] The good causes funding is distributed by the Manx Lottery Trust.[75] Tynwald receives the 12% lottery duty for tickets sold in the island.

Tourist numbers peaked in the first half of the 20th century, prior to the boom in cheap travel to Southern Europe that also saw the decline of tourism in many similar English seaside resorts. The Isle of Man tourism board has recently invested in "Dark Sky Discovery" sites to diversify its tourism industry. It is expected that dark skies will generally be nominated by the public across the UK. However, the Isle of Man tourism board tasked someone from their team to nominate 27 places on the island as a civil task. This cluster of the highest quality "Milky Way" sites[76] is now well promoted within the island. This government push has effectively given the island a headstart in the number of recognised Dark Sky sites. However, this has created a distorted view when compared to the UK where this is not promoted on a national scale. There, Dark Sky sites are expected to be nominated over time by the public across a full range of town, city and countryside locations rather than en masse by government departments.[77]

The Isle of Man is seen to be "accommodating"[78] towards Bitcoin, which is a growing technology on the island.[79]

In 2017 an office of The International Stock Exchange was opened to provide a boost for the island's finance industry.[80]

Communications

The main telephone provider on the Isle of Man is Manx Telecom. The island has two mobile operators: Manx Telecom, previously known as Manx Pronto, and Sure. Cloud9 operated as a third mobile operator on the island for a short time, but has since withdrawn. Broadband internet services are available through four local providers: Wi-Manx, Domicilium, Manx Computer Bureau and Manx Telecom. The island does not have its own ITU country code, but is accessed via the British country code (+44), and the island's telephone numbers are part of the British telephone numbering plan, with local dialling codes 01624 for landlines and 07524, 07624 and 07924 for mobiles. Calls to the island from the UK however, are generally charged differently from those within the UK, and may or may not be included in any "inclusive minutes" packages.[81][82]

In 1996, the Isle of Man Government obtained permission to use the .im national top-level domain (TLD), and has ultimate responsibility for its use. The domain is managed from day to day by Domicilium, an island-based internet service provider.

In December 2007, the Manx Electricity Authority and its telecommunications subsidiary, e-llan Communications, commissioned the laying of a new fibre-optic link that connects the island to a worldwide fibre-optic network.

The Isle of Man has three radio stations: Manx Radio, Energy FM and 3 FM.

There is no insular television service, but local transmitters retransmit British mainland digital broadcasts via the free-to-air digital terrestrial service Freeview. The Isle of Man is served by BBC North West for BBC One and BBC Two television services, and ITV Granada for ITV.

Many television services are available by satellite, such as Sky, and Freesat from the group of satellites at 28.2° East, as well as services from a range of other satellites around Europe such as the Astra satellites at 19.2° east and Hotbird.

The Isle of Man has three newspapers, all weeklies, and all owned by Isle of Man Newspapers, a division of the Edinburgh media company Johnston Press.[83] The Isle of Man Courier (distribution 36,318) is free and distributed to homes on the island. The other two newspapers are Isle of Man Examiner (circulation 13,276) and the Manx Independent (circulation 12,255).[84]

Postal services are the responsibility of Isle of Man Post, which took over from the British General Post Office in 1973.

Transport

There is a comprehensive bus network, operated by the government-owned bus operator Bus Vannin.[85]

The Isle of Man Sea Terminal in Douglas has regular ferries to and from Heysham and to and from Liverpool, with a more restricted timetable operating in winter. There are also limited summer-only services to and from Belfast and Dublin. The Dublin route also operates at Christmas. At the time of the Isle of Man TT a limited number of sailings operate to and from Larne in Northern Ireland. All ferries are operated by the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company.[86]

The only commercial airport on the island is the Isle of Man Airport at Ronaldsway. There are direct scheduled and chartered flights to numerous airports in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[87]

The island has a total of 688 miles (1,107 km)[88] of public roads, all of which are paved. There is no overriding national speed limit; only local speed limits are set, and some roads have no speed limit. Rules about reckless driving and most other driving regulations are enforced in a similar way to the UK.[89] There is a requirement for regular vehicle examinations for some vehicles (similar to the MoT test in the UK).[90]

The island used to have an extensive narrow-gauge railway system, both steam-operated and electric, but the majority of the steam railway tracks were taken out of service many years ago, and the track removed. As of 2019, there is a steam railway between Douglas and Port Erin, an electric railway between Douglas and Ramsey and an electric mountain railway which climbs Snaefell.[91]

One of the oldest operating horse tram services is located on the sea front in the capital, Douglas. It was founded in 1876.[91]

Space commerce

The Isle of Man has become a centre for emerging private space travel companies.[92] A number of the competitors in the Google Lunar X Prize, a $30 million competition for the first privately funded team to send a robot to the Moon, are based on the island. The team summit for the X Prize was held on the island in October 2010.[93] In January 2011 two research space stations owned by Excalibur Almaz arrived on the island and were kept in an aircraft hangar at the airfield at the former RAF Jurby near Jurby.[94]

Electricity supply

The electricity supply on the Isle of Man is run by the Manx Electricity Authority. The Isle of Man is connected to Great Britain's national grid by a 40 MW alternating current link (Isle of Man to England Interconnector). There are also hydroelectric, natural gas and diesel generators. The government has also planned a 700 MW offshore wind farm, roughly half the size of Walney Wind Farm.[79]

Culture

The culture of the Isle of Man is often promoted as being influenced by its Celtic and, to a lesser extent, its Norse origins. Proximity to the UK, popularity as a UK tourist destination in Victorian times, and immigration from Britain has meant that the cultures of Great Britain have been influential at least since Revestment. Revival campaigns have attempted to preserve the surviving vestiges of Manx culture after a long period of Anglicisation, and there has been significantly increased interest in the Manx language, history and musical tradition.

Language

The official language of the Isle of Man is English. Manx has traditionally been spoken but has been stated to be "critically endangered".[95] However it now has a growing number of young speakers.

Manx is a Goidelic Celtic language and is one of a number of insular Celtic languages spoken in the British Isles.[96] Manx has been officially recognised as a legitimate autochthonous regional language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, ratified by the United Kingdom on 27 March 2001 on behalf of the Isle of Man government.[97]

Manx is closely related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic, but is orthographically sui generis.

On the island, the Manx greetings moghrey mie (good morning) and fastyr mie (good afternoon) can often be heard.[98] As in Irish and Scottish Gaelic, the concepts of "evening" and "afternoon" are referred to with one word.[99] Two other Manx expressions often heard are Gura mie eu ("Thank you"; familiar 2nd person singular form Gura mie ayd) and traa dy liooar, meaning "time enough", this represents a stereotypical view of the Manx attitude to life.[100][101]

In the 2011 Isle of Man census, approximately 1,800 residents could read, write, and speak the Manx language.[102]

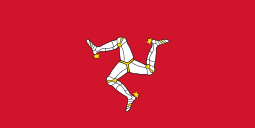

Symbols

For centuries, the island's symbol has been the so-called "three legs of Mann" (Manx: Tree Cassyn Vannin), a triskelion of three legs conjoined at the thigh. The Manx triskelion, which dates back with certainty to the late 13th century, is of uncertain origin. It has been suggested that its origin lies in Sicily, an island which has been associated with the triskelion since ancient times.[103][104]

The symbol appears in the island's official flag and official coat of arms, as well as its currency. The Manx triskelion may be reflected in the island's motto, Latin: Quocunque jeceris stabit, which appears as part of the island's coat of arms. The Latin motto translates into English as "whichever way you throw, it will stand"[105] or "whithersoever you throw it, it will stand".[106] It dates to the late 17th century when it is known to have appeared on the island's coinage.[105] It has also been suggested that the motto originally referred to the poor quality of coinage which was common at the time—as in "however it is tested it will pass".[107]

Religion

The predominant religious tradition of the island is Christianity. Before the Protestant Reformation, the island had a long history as part of the unified Western Church, and in the years following the Reformation, the religious authorities on the island, and later the population of the island, accepted the religious authority of the British monarchy and the Church of England.[109] It has also come under the influence of Irish religious tradition. The island forms a separate diocese called Sodor and Man, which in the distant past comprised the medieval kingdom of Man and the Scottish isles ("Suðreyjar" in Old Norse). It now consists of 16 parishes,[110] and since 1541[111] has formed part of the Province of York.[112] (These modern ecclesiastical parishes do not correspond to the island's ancient parishes mentioned in this article under "Local Government", but more closely reflect the current geographical distribution of population.)

Other Christian churches also operate on the Isle of Man. The second largest denomination is the Methodist Church, whose Isle of Man District is close in numbers to the Anglican diocese. There are eight Catholic parish churches, included in the Catholic Archdiocese of Liverpool,[113] as well as a presence of Eastern Orthodox Christians. Additionally there are five Baptist churches, four Pentecostal churches, the Salvation Army, a ward of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, two congregations of Jehovah's Witnesses, two United Reformed churches, as well as other Christian churches. There is a small Muslim community, with its own mosque in Douglas, and there is also a small Jewish community; see history of the Jews in the Isle of Man.[114]

Myth, legend and folklore

In Manx mythology, the island was ruled by the sea god Manannán, who would draw his misty cloak around the island to protect it from invaders. One of the principal folk theories about the origin of the name Mann is that it is named after Manannán.

In the Manx tradition of folklore, there are many stories of mythical creatures and characters. These include the Buggane, a malevolent spirit which, according to legend, blew the roof off St Trinian's Church in a fit of rage; the Fenodyree; the Glashtyn; and the Moddey Dhoo, a ghostly black dog which wandered the walls and corridors of Peel Castle.

The Isle of Man is also said to be home to fairies, known locally as "the little folk" or "themselves". There is a famous Fairy Bridge, and it is said to be bad luck if one fails to wish the fairies good morning or afternoon when passing over it. It used to be a tradition to leave a coin on the bridge to ensure good luck. Other types of fairies are the Mi'raj and the Arkan Sonney.

An old Irish story tells how Lough Neagh was formed when Ireland's legendary giant Fionn mac Cumhaill (commonly anglicised to Finn McCool) ripped up a portion of the land and tossed it at a Scottish rival. He missed, and the chunk of earth landed in the Irish Sea, thus creating the island.

Peel Castle has been proposed as a possible location of the Arthurian Avalon[115] or as the location of the Grail Castle, site of Lancelot's encounter with the sword bridge of King Maleagant.[116]

One of the most often-repeated myths is that people found guilty of witchcraft were rolled down Slieau Whallian, a hill near St John's, in a barrel. However this is a 19th-century legend which comes from a Scottish legend, which in turn comes from a German legend. It never happened. Separately, a witchcraft museum was opened at the Witches Mill, Castletown in 1951. There has never actually been a witches' coven on that site; the myth was only created with the opening of the museum.[117] However, there has been a strong tradition of herbalism and the use of charms to prevent and cure illness and disease in people and animals.[118][119]

Music

The music of the Isle of Man reflects Celtic, Norse and other influences, including from its neighbours, Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales. A wide range of music is performed on the island, such as rock, blues, jazz and pop.

Its traditional folk music has undergone a revival since the 1970s, starting with a music festival called Yn Chruinnaght in Ramsey.[120] This was part of a general revival of the Manx language and culture after the death of the last native speaker of Manx in 1974.

The Isle of Man was mentioned in the Who song "Happy Jack" as the homeland of the song's titular character, who is always in a state of ecstasy, no matter what happens to him. The song 'The Craic was 90 in the Isle of Man' by Christy Moore describes a lively visit during the Island's tourism heyday. The Island is also the birthplace of Maurice, Robin and Barry Gibb, of the Bee Gees.

Food

In the past, the basic national dish of the island was spuds and herrin, boiled potatoes and herring. This plain dish was supported by the subsistence farmers of the island, who crofted the land and fished the sea for centuries. A more recent claim for the title of national dish could be the ubiquitous chips, cheese and gravy. This dish, which is similar to poutine, is found in most of the island's fast-food outlets, and consists of thick cut chips, covered in shredded Manx Cheddar cheese and topped with a thick gravy.[121] However, as of the Isle of Man Food & Drink Festival 2018, queenies have been crowned the Manx national dish.[122]

Seafood has traditionally accounted for a large proportion of the local diet. Although commercial fishing has declined in recent years, local delicacies include Manx kippers (smoked herring) which are produced by the smokeries in Peel on the west coast of the island, albeit mainly from North Sea herring these days.[123] The smokeries also produce other specialities including smoked salmon and bacon.

Crab, lobster and scallops are commercially fished, and the queen scallop (queenies) is regarded as a particular delicacy, with a light, sweet flavour.[124] Cod, ling and mackerel are often angled for the table, and freshwater trout and salmon can be taken from the local rivers and lakes, supported by the government fish hatchery at Cornaa on the east coast.

Cattle, sheep, pigs and poultry are all commercially farmed; Manx lamb from the hill farms is a popular dish. The Loaghtan, the indigenous breed of Manx sheep, has a rich, dark meat that has found favour with chefs,[125][126] featuring in dishes on the BBC's MasterChef series.

Manx cheese has also found some success, featuring smoked and herb-flavoured varieties, and is stocked by many of the UK's supermarket chains.[127][128][129] Manx cheese took bronze medals in the 2005 British Cheese Awards, and sold 578 tonnes over the year. Manx cheddar has been exported to Canada where it is available in some supermarkets.[130]

Beer is brewed on a commercial scale by Okells Brewery, which was established in 1850 and is the island's largest brewer; and also by Bushy's Brewery and the Hooded Ram Brewery. The Isle of Man's Pure Beer Act of 1874, which resembles the German Reinheitsgebot, is still in effect: under this Act, brewers may only use water, malt, sugar and hops in their brews.[131]

Sport

The Isle of Man is represented as a nation in the Commonwealth Games and the Island Games and hosted the IV Commonwealth Youth Games in 2011. Manx athletes have won three gold medals at the Commonwealth Games, including the one by cyclist Mark Cavendish in 2006 in the Scratch race. The Island Games were first held on the island in 1985, and again in 2001. In 2019, FC Isle of Man was founded and is a North West Counties League team.

.jpg)

Isle of Man teams and individuals participate in many sports both on and off the island including rugby union, football, gymnastics, field hockey, netball, taekwondo, bowling, obstacle course racing and cricket. It being an island, many types of watersports are also popular with residents.

Motorcycle racing

The main international event associated with the island is the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy race, colloquially known as "The TT",[132] which began in 1907. It takes place in late May and early June. The TT is now an international road racing event for motorcycles, which used to be part of the World Championship, and is long considered to be one of the "greatest motorcycle sporting events of the world".[133] Taking place over a two-week period, it has become a festival for motorcycling culture, makes a huge contribution to the island's economy and has become part of Manx identity.[134] For many, the Isle carries the title "road racing capital of the world".[135]

The Manx Grand Prix is a separate motorcycle event for amateurs and private entrants that uses the same 60.70 km (37.72 mi)[136] Snaefell Mountain Course in late August and early September.

Cammag

Prior to the introduction of football in the 19th century, Cammag was the island's traditional sport.[137] It is similar to the Irish hurling and the Scottish game of shinty. Nowadays there is an annual match at St John's.

Cinema

The Isle of Man has two cinemas, both in Douglas. The Broadway Cinema is located in the government-owned and -run Villa Marina and Gaiety Theatre complex. It has a capacity of 154 and also doubles as a conference venue.[138]

The Palace Cinema is located next to the derelict Castle Mona hotel and is operated by the Sefton Group. It has two screens: Screen One holds 293 customers, while Screen Two is smaller with a capacity of just 95. It was extensively refurbished in August 2011.[139]

Fauna

Two domestic animals are specifically connected to the Isle of Man, though they are also found elsewhere.

The Manx cat is a breed of cat noted for its genetic mutation that causes it to have a shortened tail. The length of this tail can range from a few inches, known as a "stumpy", to being completely nonexistent, or "rumpy". Manx cats display a range of colours and usually have somewhat longer hind legs compared to most cats. The cats have been used as a symbol of the Isle of Man on coins and stamps and at one time the Manx government operated a breeding centre to ensure the continuation of the breed.[140]

The Manx Loaghtan sheep is a breed native to the island. It has dark brown wool and four, or sometimes six, horns. The meat is considered to be a delicacy.[141] There are several flocks on the island and others have been started in England and Jersey.

A more recent arrival on the island is the red-necked wallaby, which is now established on the island following an escape from the Wildlife Park.[142] The local police report an increasing number of wallaby-related calls.[143]

There are also many feral goats in Garff, a matter which was raised in Tynwald Court in January 2018.[144]

In March 2016, the Isle of Man became the first entire territory to be adopted into UNESCO's Network of Biosphere Reserves.[145]

Demographics

Age structure

- 0–14 years: 16.27% (male 7,587 /female 6,960)

- 15–24 years: 11.3% (male 5,354 /female 4,750)

- 25–54 years: 38.48% (male 17,191 /female 17,217)

- 55–64 years: 13.34% (male 6,012 /female 5,919)

- 65 years and over: 20.6% (male 8,661 /female 9,756) (2018 est.)[146]

Population density

- 131 people/km2 (339 people/sq mi) (2005 est.)

Sex ratio

| Age range | Ratio |

|---|---|

| At birth | 1.08 |

| 0-14 | 1.09 |

| 15-24 | 1.13 |

| 25-54 | 1.00 |

| 55–64 years | 1.02 |

| 65+ | 0.89 |

| Total population | 1 (2018 est.)[146] |

Infant mortality rate

- Total: 4 deaths/1,000 live births

- Male: 4 deaths/1,000 live births

- Female: 4 deaths/1,000 live births (2018 est.)

- Country comparison to the world: 191[146]

Life expectancy at birth

- total population: 81.4 years

- male: 79.6 years

- female: 83.3 years (2018 est.)

- country comparison to the world: 29

- Total fertility rate: 1.92 children born/woman (2018 est.)[146]

Nationality

- noun: Manxman (men), Manxwoman (women)

- adjective: Manx

Climate

The Isle of Man has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb). Average rainfall is higher than averaged over the territory of the British Isles, because the Isle of Man is far enough from Ireland for the prevailing south-westerly winds to accumulate moisture. Average rainfall is highest at Snaefell, where it is around 1,900 millimetres (75 in) a year. At lower levels it can be around 800 millimetres (31 in) a year. The highest recorded temperature was 28.9 °C (84.0 °F) at Ronaldsway on 12 July 1983.

On 10 May 2019 Chief Minister Howard Quayle stated that the Isle of Man Government recognises that a state of emergency exists due to the threat of anthropogenic climate change.[147]

| Climate data for Isle of Man (Ronaldsway) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 82.6 (3.25) |

57.5 (2.26) |

65.5 (2.58) |

55.7 (2.19) |

50.9 (2.00) |

58.1 (2.29) |

56.2 (2.21) |

65.3 (2.57) |

75.3 (2.96) |

102.5 (4.04) |

103.1 (4.06) |

91.8 (3.61) |

864.4 (34.03) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.0 | 10.6 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 14.1 | 15.2 | 13.9 | 140.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 54.1 | 77.9 | 115.9 | 171.2 | 227.6 | 203.4 | 197.4 | 184.9 | 138.9 | 103.6 | 63.5 | 46.0 | 1,584.6 |

| Source 1: Met Office[148] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Météo Climat[149] | |||||||||||||

References

- "2016 Isle of Man Census Report" (PDF). Gov.im. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Income Inequalities". The Poverty Site. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). HDR.UNDP.org. United Nations Development Programme. p. 143 ff. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- "Magnus 3 Olavsson Berrføtt – Norsk biografisk leksikon". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). 28 September 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Tynwald, the parliament of the Isle of Man: Adult suffrage". Tynwald.org.im. 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- In 1893 New Zealand became the first country to grant all women the vote.

- "UNESCO: Isle of Man biosphere reserve". Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Isle of Man: National Income Report" (PDF). gov.im. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Williams, David (3 October 2017). "Great British drives: Isle of Man". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

The Isle of Man is best known, of course, for its famous race, the annual Tourist Trophy, or 'TT'.

-

Long, Peter (1998). "Isle of Man". The Hidden Places of England. Hidden Places - National Guides (4 ed.). Aldermaston: Travel Publishing Ltd (published 2004). p. 281. ISBN 9781904434122. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

Best known for its motorcycle races, its tailless cats and its kippers [...].

- Minahan, James (31 January 2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313309847 – via Google Books.

- Kinvig, R. H. (1975). The Isle of Man: A Social, Cultural and Political History (3rd ed.). Liverpool University Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-85323-391-8.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 676. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

-

Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). "The Place Names of Roman Britain". Batsford: 410–411. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Moore 1903:84 Sacheverell 1859:119–120 Waldron 1726:1 Kinvig, R. H. (1975). The Isle of Man. A Social, Cultural and Political History (3rd ed.). Liverpool University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-85323-391-8.

- Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch: Record number 1277 (Root / lemma: men-1)

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 679. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Kneale, Victor (2006). "Ellan Vannin (Isle of Man). Britonia". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 676. The Old Irish name Manandán is often interpreted as 'He of [the isle of] Mann'. If the name of Mann reflects the generic word for 'mountain', it is impossible to distinguish this from a generic 'he of the mountain'; but the patronymic mac Lir, interpreted as 'son of the Sea', is taken to reinforce the association with the island. See, e.g.: Wagner, Heinrich. "Origins of Pagan Irish Religion". Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie. v. 38. 1-28.

- Cited after Catholic World 37 (1883) p. 261.

- The Dublin Review. 57. W. Spooner. 1865. p. 83.

- Bradley, Richard (2007). The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-84811-4.

- "Hunter Gatherers". Isle of Man Government Manx National Heritage. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2019.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "First Farmers". Isle of Man Government Manx National Heritage. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2019.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Home - Manx National Heritage". Manx National Heritage. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Esmonde Cleary, A.; Warner, R.; Talbert, R.; Gillies, S.; Elliott, T.; Becker, J. "Manavia Insula". Pleides. Pleiades. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "Celtic Farmers". Isle of Man Government Manx National Heritage. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2019.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Barron, Evan MacLeod (1997). The Scottish War of Independence. Barnes & Noble. p. 411.

- "Geography – Isle of Man Public Services". Gov.im. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Archer, Mike (2010). Bird Observatories of Britain and Ireland (2nd ed.). A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-1040-9.

-

"Snaefell Mountain Railway". Isle of Man Guide. Maxima Systems. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

From the top on a clear day it is said one can see the six kingdoms. The kingdom of Scotland, England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Mann and Heaven.

- "Snaefell Mountain Railway". VisitIsleOfMan.com. Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- "Snaefell Summit". Isle-of-Man.com. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

It is the answer to the often posed question as to where can one see seven kingdoms at the same time? The seven Kingdoms being the four mentioned by Earl James, the Kingdom of Man, of Earth (in some answers that of Neptune) and of Heaven.

- "Isle of Man Government website". Isleofmanfinance.gov.im. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Taking Liberties - Star Items - Chronicle of Mann". BL.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Framework for developing the international identity of the Isle of Man" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- Royal Commission on the Constitution 1969–1973, Volume I, Report (Cmnd 5460) (Report). London. 1973.

- "HMS Ramsey". Royal Navy. 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- "Regimental Museum – History". Isle of Man Guide. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- See "The Forgotten Army: Fencible Regiments of Great Britain 1793-1816". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 15 August 2019. for more detail.

- Scobie, Ian Hamilton Mackay (1914). "An Old Highland Fencible Corps: The history of the Reay Fencible Highland Regiment of Foot, or Mackay's Highlanders, 1794–1802, with an account of its services in Ireland during the rebellion of 1798". Edinburgh: Blackwood: 363. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)|date=December 2017}} - "Regiments stationed on Isle of Man, 1765-1896". Isle-of-man.com. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "British Army opens first reserve unit opens on Isle of Man since 1968". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. October 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Isle of Man Relationship with the European Union" (PDF). www.gov.im.

- EU referendum: Brexit sends IoM on 'unknown journey, BBC News, 24 June 2016

- "Manx government explanation of Protocol 3" (PDF). Gov.im. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Isle of Man Facts & Economic Data". Isle of Man Finance. Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- "Immigration in the Isle of Man" (PDF). Isle of Man Government. October 2006. p. 12. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- "Legislating for the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union" (PDF). Department for Exiting the European Union. 30 March 2017.

- "Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union" (PDF). European Commission. 14 November 2018.

- "Isle of Man Government - EU Exit and the Transition Period". www.gov.im. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "The role and future of the Commonwealth". House of Commons. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Written evidence from the States of Guernsey". Policy Council of Guernsey. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Isle of Man welcomes report on Commonwealth future". Isle of Man Government. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Isle of Man Green Party elects first councillor Andrew Bentley". BBC News. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Mec Vannin". Mecvannin.im. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "PAG - Positive Action Group - Isle of Man - Positive Action Group - Isle of Man - Pag, Credit, Agreement, User, February". Positiveactiongroup.org. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Department of Education and Children Home Page". Isle of Man Government Department of Education and Children. 21 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Healthcare on the Isle of Man". LOcate IM. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Emergency services". Isle of Man Government. 16 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Welcome to the Isle of Man Constabulary". Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on 3 March 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- "More staff trained to operate island's crematorium". BBC News. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Isle of Man: Key sectors". Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "2016 Isle of Man Census Presentation" (PDF). Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Isle of Man Manufacturing Sector". whereyoucan.im (Department for Enterprise). Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Financial Services Sector - Isle of Man. Where You Can". Gov.im. IsleofMan Government. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Isle of Man Government: Rates & Allowances 2017/2018". Gov.im. Isle of Man Government. 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Isle of Man Government: Corporate Tax Rules". Gov.im. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Isle of Man Film". 27 September 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Isle of Man Digital Media Cluster. Strategic Directions for the Isle of Man" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "ontheisleofman.com". Ontheisleofman.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "UK National Lottery Diary". Merseyworld.com. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "National Lottery FAQ:Can I play while overseas?". National-lottery.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "BBC News - Manx charities to benefit from lottery". BBC News. 20 June 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "House of Lords - Constitution - Ninth Report". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "About". MLT.org.im. Manx Lottery Trust. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Dark Sky Discovery Sites". Darkskydiscovery.org.uk. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Stargazing Sites in the Isle of Man - Isle of Man". Visitisleofman.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Global Bitcoin Regulations". Bitcoinregulation.world. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Isle of Man Offshore Wind Farm". 4C Offshore. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Carolyn Gelling to lead new stock exchange company". IOMToday. 9 March 2017.

- "Phone Tariff Residential" (PDF). BT.com. BT Group.

- "Calling abroad from the UK". O2.com. Telefónica Europe.

- "Our Business". Johnston Press. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Isle of Man Newspapers". IOMToday. Isle of Man Newspapers. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- "Isle of Man Government - Bus and Rail". Gov.im. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- "Steam Packet Company". Steam-packet.com. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Isle of Man Government - Isle of Man Airport". Gov.im. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Isle of Man – About the Island". Isleofman.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Driving on the Isle of Man". Isle of Man Guide. Maxima Systems. 2005. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "Vehicle examination". Isle of Man Government. 1 January 1988. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Heritage Railways". Gov.im. Isle of Man Government. 2017. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Goodman, Mike (22 July 2011). "Lift-off for Isle of Man's quest to join space race". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Lunar Entrepreneurs Converge on Isle of Man for Google Lunar X PRIZE Summit". GoogleLunarXPrize.com. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Research space stations arrive on Isle of Man". BBC News. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "UNESCO accepts Manx language is not 'extinct'". Isle of Man Government. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- Carpenter, Rachel N. (2011). "Mind Your P's and Q's: Revisiting the Insular Celtic hypothesis through working towards an original phonetic reconstruction of Insular Celtic" (PDF). Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Kelly, Phil. "Manx today by Phil Kelly". BBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Davies, Alan (2007). An Introduction to Applied Linguistics (2nd The Manx ed.). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3354-8.

- "Manx Culture". VisitIsleOfMan.com. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Arthur William, Moore (1971). The Folk-Lore of the Isle of Man (Reprint ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 274. ISBN 1-60506-183-2.

- "Moscow Manx cheese". IOMToday. 8 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- "Isle of Man Census Report 2011" (PDF). Gov.im. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Fiorentini, Graziella; De Miro, Ernesto; Calderone, Anna; Caccamo Caltabiano, Maria, eds. (2003). Archeologia del Mediterraneo: Studi in onore di Ernesto De Miro. L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 735–736. ISBN 978-88-8265-134-3.|date=December 2017}}

- Wilson, RJA (2000). "On the Trail of the Triskeles: From the McDonald Institute to Archaic Greek Sicily". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 10 (1): 35–61. doi:10.1017/S0959774300000020.

- Kinvig, R.H. (1975). The Isle of Man: A social, cultural and political history. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle. pp. 91–92. ISBN 0-8048-1165-2.

- "Island Facts". Gov.im. Public Services, Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- "The Three Legs of Man". Isle-of-Man.com). Retrieved 15 September 2011.. This webpage cited: Wagner, A. R. (1959–1960). "The Origin of the Arms of Man". Manx Museum. 6.. This webpage also cited: Megaw, B. R. S. (1959–1960). "The Ship Seals of the Kings of Man". Manx Museum. 6.|date=December 2017}}

- Island Facts – Isle of Man Public Services. Gov.im (12 July 1996). Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Moore, A. "Diocesan Histories. Sodor and Mann".

- Gumbley, Ken (1 March 2012). "Diocese of Sodor and Man". Welcome to Kirk Braddan. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Act of Parliament (1541) 33 Hen.8 c.31

- "England-Sodor & Man". Anglican Communion. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2019.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "The Archdiocese of Liverpool". Liverpool Catholic. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Religious Faiths and Organisations". Isle of Man Government. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2003. Retrieved 15 August 2019.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Avalon's Location". Electricscotland.com. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- King Arthur, Norma Lorre Goodrich, Harper and Row, 1989, p. 318

- "Manx witchcraft and sorcery probed by academic - Isle of Man Today". Iomtoday.co.im. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Nisbet, Robert A; Rhys, John (1897). "Folk-Medicine in the Isle of Man – A. W. Moore, M. A.". Yn Lioar Manninagh: The Journal of the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society. Vol 3. Douglas: Brown & Sons. pp. 303–314. OCLC 1110392917.

- Chiverrell, R.; Belchem, J.; Thomas, G.; Duffy, S.; Mytum, H. (2000). A New History of the Isle of Man: The modern period 1830-1999. A New History of the Isle of Man. Liverpool University Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-85323-726-6. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Trad music in the Isle of Man". Ceolas.org. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- isleofman.com. "Attractions :: isleofman.com". Isleofman.com. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "National Dish of the Isle of Man - Locate Isle of Man". www.locate.im. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "American Motorcyclist". American Motorcyclist : The Monthly Journal of the American Motorcyclist Association. American Motorcyclist Association: 22. November 1971. ISSN 0277-9358. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- Evans, Ann (30 May 2009). "Scallops the main ingredient of unique gathering for foodies; SUN, sea, sand and shellfish". Coventry Evening Telegraph. Coventry Newspapers. Retrieved 12 September 2011 – via TheFreeLibrary.com.

- Kallaway, Jane. "Award winning organic lamb". Langley Chase Organic Farm. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Purely Isle of Man" (PDF). Isle of Man Department of Finance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Isle of Man Oak Smoked Mature Cheddar Wins Bronze Medal at The British Cheese Awards 2010". Isle News. 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Bumper Sales for Manx Cheese". IOMToday. 15 October 2003. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Success at World Cheese Awards". IsleOfMan.com. 22 March 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "PC Black Label English Isle of Man Extra Old Cheddar Cheese". Provigo. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- "Purely Isle of Man" (PDF). Gov.im. Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Wright, David. 100 Years of the Isle of Man TT: A Century of Motorcycle Racing. The Crowood Press, 2007

- Disko, Sasha. The Image of the "Tourist Trophy" and British Motorcycling in the Weimar Republic. International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, Nov 2007

- Vaukins, Simon. The Isle of Man TT Races: Politics, Economics and National Identity. International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, Nov 2007

- Faragher, Martin. "Cultural History: Motor-Cycle Road Racing." A New History of the Isle of Man Volume V: The Modern Period 1830–1999. Ed. John Belchem. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000

- "2009 Manx Grand Prix Supplementary Regulations" (PDF). manxgrandprix.org. 2009. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "The Game of Cammag". Celticlife.ca. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- "Broadway Cinema". Gov.im. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- "Cinemas Refurbishment". Iomtoday.co.im. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- Commings, Karen (1999). Manx Cats: Everything about Purchase, Care, Nutrition, Grooming, and Behavior. Barron's Educational. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-0764107535.

- "Farming the Manx Loaghtan sheep". BBC News. 16 November 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Wallabies flourishing in the wild on Isle of Man". The Guardian. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Marshall, Francesca (7 September 2018). "Calls for wallaby warning signs to be implemented on the Isle of Man to tackle growing numbers". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Tynwald Hansard 16 January 2018, Question 9

- Morris, Hugh. "Isle of Man awarded UNESCO status". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- "Europe :: Isle of Man". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "This is a climate change emergency". In the Manx Independent this week. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Ronaldsway 1981–2010 averages". Station, District and Regional Averages 1981–2010. Met Office. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "Météo climat stats Isle of Man records". Météo Climat. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Moore, Arthur William (1903). Manx Names (Revised Cheap ed.). London: Elliot Stock (published 1906) – via Google Books.

- Sacheverell, William (1859). Cumming, Joseph George (ed.). An Account of the Isle of Man. Douglas: The Manx Society – via Google Books.

- Waldron, George (1726). Harrison, William (ed.). A Description of the Isle of Man. Douglas: The Manx Society (published 1865) – via Google Books.

Further reading

- Russel, G. (1988). "Distribution and development of some Manx epiphyte populations". Helgolander Meeresunters. 42 (3–4): 477–492. Bibcode:1988HM.....42..477R. doi:10.1007/BF02365622.

- Goodwin, Sarah (2011). A Brief History of the Isle of Man. Surrey: Loaghtan Books. ISBN 978-1-908060-00-6.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Isle of Man. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isle of Man. |

- Manx Government: A comprehensive site covering many aspects of Manx life from fishing to financial regulation

- "Europe :: Isle of Man". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 25 July 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- Isle of Man News

- Information on the work and duties of Members of the House of Keys

- Images of the Isle of Man at the English Heritage Archive

Countries.png)