Judiciary of Italy

In Italy, judges are public officials and, since they exercise one of the sovereign powers of the State, only Italian citizens are eligible for judgeship. In order to become a judge, applicants must obtain a degree of higher education as well as pass written and oral examinations. However, most training and experience is gained through the judicial organization itself. The potential candidates then work their way up from the bottom through promotions.[1] Italy's independent judiciary enjoys special constitutional protection from the executive branch. Once appointed, judges serve for life and cannot be removed without specific disciplinary proceedings conducted in due process before the Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura. The Ministry of Justice handles the administration of courts and judiciary, including paying salaries and constructing new courthouses. The Ministry of Justice and that of the Infrastructures fund and the Ministry of Justice and that of the Interiors administer the prison system. Lastly, the Ministry of Justice receives and processes applications for presidential pardons and proposes legislation dealing with matters of civil or criminal justice.

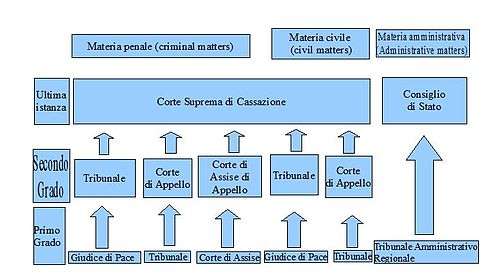

The structure of the Italian judiciary is divided into three tiers:

- Inferior courts of original and general jurisdiction

- Intermediate appellate courts which hear cases on appeal from lower courts

- Courts of last resort which hear appeals from lower appellate courts on the interpretation of law.

Italian Republic

|

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Italy |

| Constitution |

|

| Foreign relations |

|

Related topics |

Glossary of key terms

Note: There exist significant problems with applying non-Italian terminology and concepts related to law and justice to the Italian justice system. For that reason, some of the words used in the rest of the article shall be defined.

- Appello (appeal): for almost all courts in Italy (except very minor cases), it is possible to appeal the ruling, both for disagreement on how the court appreciated the facts or on disagreements with how the court interpreted the law.

- Avvocatura dello Stato: the public organ, composed of lawyers, which represents the State, whenever it is plaintiff or defendant in a lawsuit.[2]

- Cassazione: the Court of Cassazione acts as cassation jurisdictions, which means that it has supreme jurisdiction on quashing the judgments of inferior courts if those courts misapplied law. Generally, cassation is based not on outright violations of law, but on diverging interpretations of law between the courts. Cassation is not based on the facts of the case. Cassation is always open as a final recourse.

- Codice ("law code"): collection of enacted statutory law or regulations relating to a single topic. Modern Italian law codes date back to the 19th century (Pisanelli Code, the first civil code of the Kingdom of Italy and Zanardelli Code, the first penal code), though all codes have since been abolished and substituted.

- Contraddittorio (due process)

- Contravvenzione ("misdemeanor, summary offence"): lowest kind of crimes punishable by fines or at most short jail sentences.

- Delitto (felony): more severe crimes, punishable by fines, prison sentences or life imprisonment.

- Giudice monocratico (solo judge).

- Giudice collegiale (panel of judges): it is important to note that, in this case, Giudice (Judge) refers both to every single person composing the panel and to the panel itself.

- Giurisprudenza (jurisprudence). While Italian judges, in keeping with the civil law tradition, do not create law, and thus there is no case law properly said, the decisions of the higher courts are of great importance and may establish long-lasting doctrine. While there is no stare decisis rule forcing lower courts to decide according to precedent, they tend to do so in practice, because, should they not do that, the higher court might quash their judgements, in keeping with its jurisprudence.

- Inamovibilità (security of tenure): Judges cannot be removed from office, except through specific disciplinary proceedings (conducted by the Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura, an independent tribunal), for infringements on their duties. They may be moved or promoted only with their own will. These protections are meant to ensure that they are independent from the executive power.

- Magistrato (judicial officer): general term encompassing Judges (Giudici) and prosecutors (Pubblici Ministeri); the Magistratura, or judiciary, is a collective term for all judicial officers. Magistrati are government employees, but statutorily kept separate and independent from the other branches of government. Magistrati are expected to maintain a certain degree of distance (as is the case with all government employees); that is, they must refrain from actions and statements that could hinder their impartiality or make it appear that their impartiality is compromised, e.g., refrain from making public political statements.

- Magistratura amministrativa (administrative courts, administrative stream): courts of this order judge most cases against the government.

- Magistratura ordinaria (judicial courts, judicial stream, literally ordinary judiciary): courts of this order judge civil and criminal cases.

- Procura della Repubblica: the Ufficio del Pubblico Ministero attached to the Courts of first instance; it is headed by a Procuratore della Repubblica and composed by many Procuratori Aggiunti, Sostituti Procuratori and Vice Procuratori.

- Procura Generale della Repubblica: the Ufficio del Pubblico Ministero attached to the Corte d'Appello; it is headed by a Procuratore Generale della Repubblica.

- Presidente di Sezione (presiding justice): chief Judge of a division of a court.

- Presidente di Tribunale or Presidente di Corte d'Appello or Primo Presidente della Corte di Cassazione: the Chief Justice of a given Court.

- Pubblicità. All civil, administrative and criminal justice, as well as all financial cases where individuals may be fined, end up with audiences open to the public. There are narrow exceptions to this requirement: cases involving national security secrets, as well as cases of rape and other sexual attacks, may be closed or partially closed to the public, respectively in order to protect the secret or in order not to add to the pain of the victim. Cases with defendants that are minors (or rather, defendants that had not reached the age of majority at the time of the crime) are not open to the public and the names of the defendants are not made public, so that they are not stigmatized for life.

- Pubblico Ministero (public prosecutor): this office can be translated into prosecutor but the functions of a Pubblico Ministero also include the general monitoring of the activity of the court in both criminal and civil cases (say, to see if Judges apply the law in a consistent manner).

- Sentenza (Judgement): it is composed of two parts; the first, the parte motiva contains the written explanation by the Judge of how and why he decided in that particular way; the other, the dispositivo, contains the Judge's orders to the parties.

- Sezione ("division"): subdivisions of a large court of general jurisdiction.

- Sezione specializzata (specialized division): a sezione, which is specialized on a specific area of law.

- Ufficio del Pubblico Ministero, (Office of the Prosecutor): responsible for the prosecution of cases. It requests enquiries to be made; during court hearings, it brings out accusations against the suspect. In addition, it has a role of general monitoring of courts.

- Tribunale: generally refers to a court of record of first instance having original jurisdiction and whose judgments are appealable; it is the only Court that can be either monocratica or collegiale, that it is to say that it can be composed of one or three Judges, according to the case it is dealing with.

Judicial stream

Civil court

Justice of the Peace

The Justice of the Peace is the court of original jurisdiction for less significant civil matters. The court replaced the old Preture (Praetor Courts) and the Giudice Conciliatore (Judge of conciliation) in 1999. This court presides over lawsuits in which claims do not exceed €5,000 in value or €15,000 in certain circumstances.

Tribunale

The Tribunale is the court of general jurisdiction for civil matters. Here, litigants are statutorily required to be represented by an Italian barrister, or avvocato. It can be composed of one Judge or of three Judges, according to the importance of the case.

When acting as Appellate Court for the Justice of the Peace, it is always monocratico (composed of only one Judge).

Divisions and Specialized Divisions

Giudice del Lavoro (Labor Tribunal): hears disputes and suits between employers and employees (apart from cases dealt with in administrative courts, see below). A single judge presides over cases in the Giudice del Lavoro tribunal.

Sezione specializzata agraria (Land Estate Court): the specialized section that hears all agrarian controversies. Cases in this court are heard by three professional Judges and two lay Judges.

Tribunale per i Minorenni (Family Proceedings Court): the specialized section that hears all cases concerning minors, such as adoptions or emancipations; it is presided over by two professional Judges and two lay Judges.

Court of Appeal

The Court has jurisdiction to retry the cases heard by the Tribunale as a Court of first instance and is divided into three or more divisions: labor, civil, and criminal.

Court of Cassation

Criminal courts

Courts of first instance

Appellate courts

References

- Guarnieri, Carlo (1997). "The judiciary in the Italian political crisis". West European Politics.

- In the constitutional review this position should be increasingly assimilated, in the event of litigation of judicial acts, as a mere ex officio defense "in the interest of the law" ( ... ) . Indeed, more and more frequently the Government does not intervene and, in fact, the duel is fought before the Court between the "real" contenders: Buonomo, Giampiero (2007). "Nuovi sviluppi in tema di conflitto tra Stato e Regione su atti giurisdizionali incidenti sull'insindacabilità". Diritto&Giustizia edizione online. – via Questia (subscription required)