Swiss franc

The franc (German: Franken, French and Romansh: franc, Italian: franco; sign: Fr. (in German language), fr. (in French, Italian, Romansh languages), or CHF in any other language, or internationally;[1] code: CHF) is the currency and legal tender of Switzerland and Liechtenstein; it is also legal tender in the Italian exclave of Campione d'Italia. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) issues banknotes and the federal mint Swissmint issues coins.

| Swiss franc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schweizer Franken (German) franc suisse (French) franco svizzero (Italian) franc svizzer (Romansh) | |||||

| |||||

| ISO 4217 | |||||

| Code | CHF | ||||

| Number | 756 | ||||

| Exponent | 2 | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1⁄100 | Rappen (German) centime (French) centesimo (Italian) rap (Romansh) | ||||

| Plural | Franken (German) francs (French) franchi (Italian) francs (Romansh) | ||||

| Rappen (German) centime (French) centesimo (Italian) rap (Romansh) | Rappen (German) centimes (French) centesimi (Italian) raps (Romansh) | ||||

| Symbol | German: Fr., Rp.[1][2] French: fr., c.[1][3] Italian: fr., ct.[1][4] Romansh: fr., rp.[1] International (any other language): CHF[1][5] | ||||

| Nickname |

| ||||

| Banknotes | 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 & 1,000 francs | ||||

| Coins | 5, 10 & 20 centimes, 1⁄2, 1, 2 & 5 francs | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Official user(s) | |||||

| Unofficial user(s) | |||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | Swiss National Bank | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Printer | Orell Füssli Arts Graphiques SA (Zürich) | ||||

| Mint | Swissmint | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Valuation | |||||

| Inflation | 0.9% in 2018 | ||||

| Source | Statistik Schweiz | ||||

The smaller denomination, a hundredth of a franc, is a Rappen (Rp.) in German, centime (c.) in French, centesimo (ct.) in Italian, and rap (rp.) in Romansh. The ISO 4217 code of the currency used by banks and financial institutions is CHF.

The official symbols Fr. (German symbol) and fr. (Latin languages) are widely used by businesses and advertisers, also for the English language. According Art. 1 SR/RS 941.101 of the federal law collection the internationally official abbreviation – besides the national languages – however is CHF,[1] also in English; respective guides also request to use the ISO 4217 code.[5][2][3][4] Outdated is the use of SFr. for Swiss Franc and fr.sv..[2][3][4] The Latinate “CH” stands for Confoederatio Helvetica. Given the different languages used in Switzerland, Latin is used for language-neutral inscriptions on its coins.

History

Before the Helvetic Republic

Before 1798, about 75 entities were making coins in Switzerland, including the 25 cantons and half-cantons, 16 cities, and abbeys, resulting in about 860 different coins in circulation, with different values, denominations and monetary systems.[6] The local Swiss currencies included the Basel thaler, Berne thaler, Fribourg gulden, Geneva thaler, Geneva genevoise, Luzern gulden, Neuchâtel gulden, St. Gallen thaler, Schwyz gulden, Solothurn thaler, Valais thaler, and Zürich thaler.

By the end of the 18th century and the 1st half of the 19th century, most of these local Swiss currencies are either mere uncoined accounting units, or local billon coins known only to residents of the issuing canton. Larger payments are done via foreign trade coins like German reichsthalers or French écus which are recognizable within and outside Switzerland. Small change, however, are in local coins which typically cannot be recognized outside the issuing canton. A guide showing the equivalence of large trade coins to local currency is found here:[7]

Bernese Rollbatzen, 15th century

Bernese Rollbatzen, 15th century Zürich Taler (1768)

Zürich Taler (1768)

Helvetic Republic to Regeneration 1798–1847

In 1798, the Helvetic Republic introduced the franc, a currency based on the Berne thaler, subdivided into 10 batzen or 100 centimes. The Swiss franc was equal to 6 3⁄4 grams of pure silver or 1 1⁄2 French francs.[8]

32 Franken gold coin of the Helvetic Republic (1800)

32 Franken gold coin of the Helvetic Republic (1800)

This franc was issued until the end of the Helvetic Republic in 1803, but served as the model for the currencies of several cantons in the Mediation period (1803–1814). These 19 cantonal currencies were the Appenzell frank, Argovia frank, Basel frank, Berne frank, Fribourg frank, Geneva franc, Glarus frank, Graubünden frank, Luzern frank, St. Gallen frank, Schaffhausen frank, Schwyz frank, Solothurn frank, Thurgau frank, Ticino franco, Unterwalden frank, Uri frank, Vaud franc, and Zürich frank.

After 1815, the restored Swiss Confederacy attempted to simplify the system of currencies once again. As of 1820, a total of 8,000 distinct coins were current in Switzerland: those issued by cantons, cities, abbeys, and principalities or lordships, mixed with surviving coins of the Helvetic Republic and the pre-1798 Helvetic Republic. In 1825, the cantons of Berne, Basel, Fribourg, Solothurn, Aargau, and Vaud formed a monetary concordate, issuing standardised coins, the so-called Konkordanzbatzen, still carrying the coat of arms of the issuing canton, but interchangeable and identical in value. The reverse side of the coin displayed a Swiss cross with the letter C in the center.

Franc of the Swiss Confederation, 1850–present

Although 22 cantons and half-cantons issued coins between 1803 and 1850, less than 15% of the money in circulation in Switzerland in 1850 was locally produced, with the rest being foreign, mainly brought back by mercenaries. In addition, some private banks also started issuing the first banknotes, so that in total, at least 8000 different coins and notes were in circulation at that time, making the monetary system extremely complicated.[9][note 4] In practice, only the larger German or French trade coins were recognized for large payments within and outside Switzerland. Local small change or banknotes were typically useful only in the issuing canton and were not accepted elsewhere.

To solve this problem, the new Swiss Federal Constitution of 1848 specified that the federal government would be the only entity allowed to issue money in Switzerland. This was followed two years later by the first Federal Coinage Act, passed by the Federal Assembly on 7 May 1850, which introduced the franc as the monetary unit of Switzerland. The franc was introduced at par with the French franc. It replaced the different currencies of the Swiss cantons, some of which had been using a franc (divided into 10 batzen and 100 centimes) which was worth 1.5 French francs.

In 1865, France, Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland formed the Latin Monetary Union, in which they agreed to value their national currencies to a standard of 4.5 grams of silver or 0.290322 grams of gold. Even after the monetary union faded away in the 1920s and officially ended in 1927, the Swiss franc remained on that standard until 1936, when it suffered its sole devaluation, on 27 September during the Great Depression. The currency was devalued by 30% following the devaluations of the British pound, U.S. dollar and French franc.[10] In 1945, Switzerland joined the Bretton Woods system and pegged the franc to the US dollar at a rate of $1 = CHF 4.30521 (equivalent to CHF 1 = 0.206418 grams of gold). This was changed to $1 = CHF 4.375 (CHF 1 = 0.203125 grams of gold) in 1949.

The Swiss franc has historically been considered a safe-haven currency, with a legal requirement that a minimum of 40% be backed by gold reserves.[11] However, this link to gold, which dated from the 1920s, was terminated on 1 May 2000 following a referendum.[12][13] By March 2005, following a gold-selling program, the Swiss National Bank held 1,290 tonnes of gold in reserves, which equated to 20% of its assets.[14]

In November 2014, the referendum on the "Swiss Gold Initiative" which proposed a restoration of 20% gold backing for the Swiss franc, was voted down.[15]

2011–2014: Big movements and capping

In March 2011, the franc climbed past the US$1.10 mark (CHF 0.91 per U.S. dollar). In June 2011, the franc climbed past US$1.20 (CHF 0.833 per U.S. dollar) as investors sought safety as the Greek sovereign debt crisis continued.[16] Continuation of the same crisis in Europe and the debt crisis in the US propelled the Swiss franc past US$1.30 (CHF 0.769 per U.S. dollar) as of August 2011, prompting the Swiss National Bank to boost the franc's liquidity to try to counter its "massive overvaluation".[17] The Economist argued that its Big Mac Index in July 2011 indicated an overvaluation of 98% over the dollar, and cited Swiss companies releasing profit warnings and threatening to move operations out of the country due to the strength of the franc.[18] Demand for francs and franc-denominated assets was so strong that nominal short-term Swiss interest rates became negative.[19]

On 6 September 2011, shortly after when the exchange rate was 1.095 CHF/€[20] and appeared to be heading for parity with the euro, the SNB set a minimum exchange rate of 1.20 francs to the euro (capping franc's appreciation), saying "the value of the franc is a threat to the economy",[21] and that it was "prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities".[22] In response to this announcement the franc fell against the euro, to 1.22 francs from 1.12 francs[23] and lost 9% against the U.S. dollar within fifteen minutes.[24] The intervention stunned currency traders, since the franc had long been regarded as a safe haven.[25]

The franc fell 8.8% against the euro, 9.5% against the dollar, and at least 8.2% against all 16 of the most active currencies on the day of the announcement. It was the largest plunge of the franc ever against the euro.[26] The SNB had previously set an exchange rate target in 1978 against the Deutsche mark and maintained it, although at the cost of high inflation.[27] Until mid-January 2015, the franc continued to trade below the target level set by the SNB,[28] though the ceiling was broken at least once on 5 April 2012, albeit briefly.[29]

End of capping

On 18 December 2014, the Swiss central bank introduced a negative interest rate on bank deposits to support its CHF ceiling.[30] However, with the euro declining in value over the following weeks, in a move dubbed Francogeddon[31][32][33][34] for its effect on markets, the Swiss National Bank abandoned the ceiling on 15 January 2015, and the franc promptly increased in value compared with the euro by 30%, although this only lasted a few minutes before part of the increase was reversed.[35] The move was not announced in advance and resulted in "turmoil" in stock and currency markets.[36] By the close of trading that day, the franc was up 23% against the euro and 21% against the US dollar.[37] The full daily appreciation of the franc was equivalent to $31,000 per single futures contract: more than the market had moved collectively in the previous thousand days.[38] The key CHF interest rate was also lowered from −0.25% to −0.75%, meaning depositors would be paying an increased fee to keep their funds in a Swiss bank account. This devaluation of the euro against the franc was expected to hurt Switzerland's large export industry. The Swatch Group, for example, saw its shares drop 15% (in Swiss franc terms) with the announcements[35] so that the share price may have increased on that day in terms of other major currencies.

The large and unexpected jump caused major losses for some currency traders. Alpari, a Russian-owned spread betting firm established in the UK, temporarily declared insolvency before announcing its desire to be acquired (and later denied rumours of an acquisition) by FXCM.[39][40] FXCM was bailed out by its parent company.[41] Saxo Bank of Denmark reported losses on 19 January 2015.[42] New Zealand foreign exchange broker Global Brokers NZ announced it "could no longer meet New Zealand regulators' minimum capital requirements" and terminated its business.[43]

Media questioned the ongoing credibility of the Swiss central bank,[44] and indeed central banks in general. Using phrases like "extend-and-pretend" to describe central bank exchange rate control measures, Saxobank chief economist Steen Jakobsen said, "As a group, central banks have lost credibility and when the ECB starts QE this week, the beginning of the end for central banks will be well under way".[45] BT Investment Management's head of income and fixed interest Vimal Gor said, "Central banks are becoming more and more impotent. It also ultimately proves that central banks cannot drive economic growth like they think they can".[45] UBS interest rate strategist Andrew Lilley commented, "central banks can have inconsistent goals from one-day to another".[45]

Coins

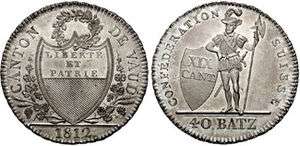

Coins of the Helvetic Republic

Between 1798 and 1803, billon coins were issued in denominations of 1 centime, 1⁄2 batzen, and 1 batzen. Silver coins were issued for 10, 20 and 40 batzen, with the 40-batzen coin also issued with the denomination given as 4 francs. Gold 16- and 32-franc coins were issued in 1800.[46]

Coins of the Swiss Confederation

In 1850, coins were introduced in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 centimes and 1⁄2, 1, 2, and 5 francs, with the 1 and 2 centimes struck in bronze, the 5, 10, and 20 centimes in billon (with 5% to 15% silver content), and the franc denominations in .900 fine silver. Between 1860 and 1863, .800 fine silver was used, before the standard used in France of .835 fineness was adopted for all silver coins except the 5 francs (which remained .900 fineness) in 1875. In 1879, billon was replaced by cupronickel in the 5 and 10 centimes and by nickel in the 20 centimes.[47] Gold coins in denominations of 10, 20, and 100 francs, known as Vreneli, circulated until 1936.[48]

Both world wars only had a small effect on the Swiss coinage, with brass and zinc coins temporarily being issued. In 1931, the size of the 5-franc coin was reduced from 25 grams to 15, with the silver content reduced to .835 fineness. The next year, nickel replaced cupronickel in the 5 and 10 centimes.[49]

In the late 1960s, the prices of internationally traded commodities rose significantly. A silver coin's metal value exceeded its monetary value, and many were being sent abroad for melting, which prompted the federal government to make this practice illegal.[50] The statute was of little effect, and the melting of francs only subsided when the collectible value of the remaining francs again exceeded their material value.

The 1-centime coin was still produced until 2006, albeit in ever decreasing quantities, but its importance declined. Those who could justify the use of 1-centime coins for monetary purposes could obtain them at face value; any other user (such as collectors) had to pay an additional four centimes per coin to cover the production costs, which had exceeded the actual face value of the coin for many years. The coin fell into disuse in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but was only officially fully withdrawn from circulation and declared to be no longer legal tender on 1 January 2007. The long-forgotten 2-centime coin, not minted since 1974, was demonetized on 1 January 1978.[49]

The designs of the coins have changed very little since 1879. Among the notable changes were new designs for the 5-franc coins in 1888, 1922, 1924 (minor), and 1931 (mostly just a size reduction). A new design for the bronze coins was used from 1948. Coins depicting a ring of stars (such as the 1-franc coin seen beside this paragraph) were altered from 22 stars to 23 stars in 1983; since the stars represent the Swiss cantons, the design was updated when in 1979 Jura seceded from the Canton of Bern and became the 23rd canton of the Swiss Confederation.[49]

The 10-centime coins from 1879 onwards (except the years 1918–19 and 1932–39) have had the same composition, size, and design until 2014 and are still legal tender and found in circulation.[49]

All Swiss coins are language-neutral with respect to Switzerland's four national languages, featuring only numerals, the abbreviation "Fr." for franc, and the Latin phrases Helvetia or Confœderatio Helvetica (depending on the denomination) or the inscription Libertas (Roman goddess of liberty) on the small coins. The name of the artist is present on the coins with the standing Helvetia and the herder.[51]

In addition to these general-circulation coins, numerous series of commemorative coins have been issued, as well as silver and gold coins. These coins are no longer legal tender, but can in theory be exchanged at face value at post offices, and at national and cantonal banks,[52] although their metal or collectors' value equals or exceeds their face value.

| Value | Diameter (mm) |

Thickness (mm) |

Weight (g) |

Composition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 centimes | 17.15 | 1.25 | 1.8 | Aluminium bronze | Made in cupronickel or pure nickel until 1980 |

| 10 centimes | 19.15 | 1.45 | 3 | Cupronickel | Made in current minting since 1879 |

| 20 centimes | 21.05 | 1.65 | 4 | Cupronickel | |

| 1⁄2 franc (50 centimes) |

18.20 | 1.25 | 2.2 | Cupronickel | In silver until 1967 |

| 1 franc | 23.20 | 1.55 | 4.4 | Cupronickel | In silver until 1967 |

| 2 francs | 27.40 | 2.15 | 8.8 | Cupronickel | In silver until 1967 |

| 5 francs | 31.45 | 2.35 | 13.2 | Cupronickel | In silver until 1967 and in 1969; 25 g weight until 1930 |

Banknotes

.jpg)

In 1907, the Swiss National Bank took over the issuance of banknotes from the cantons and various banks. It introduced denominations of 50, 100, 500 and 1000 francs.[54] 20-franc notes were introduced in 1911, followed by 5-franc notes in 1913.[55] In 1914, the Federal Treasury issued paper money in denominations of 5, 10 and 20 francs. These notes were issued in three different versions: French, German and Italian.[56] The State Loan Bank also issued 25-franc notes that year. In 1952, the national bank ceased issuing 5-franc notes but introduced 10-franc notes in 1955. In 1996, 200-franc notes were introduced whilst the 500-franc note was discontinued.

Eight series of banknotes have been printed by the Swiss National Bank, six of which have been released for use by the general public. The sixth series from 1976, designed by Ernst and Ursula Hiestand, depicted persons from the world of science. This series was recalled on 1 May 2000 and is no longer legal tender, but notes can still be exchanged for valid ones of the same face value at any National Bank branch or authorized agent, or mailed in by post to the National Bank in exchange for a bank account deposit. The exchange program will end on 30 April 2020, after which sixth-series notes will lose all value.[57] As of 2016, 1.1 billion francs' worth of sixth-series notes had not yet been exchanged, even though they had not been legal tender for 16 years and only 4 more years remained to exchange them. To avoid having to expire such large amounts of money in 2020, the Federal Council (cabinet) and National Bank proposed in April 2017 to remove the time limit on exchanges for the sixth and future recalled series; this proposal is still in the draft bill stage as of early 2018.[58][59]

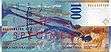

The seventh series was printed in 1984, but kept as a "reserve series", ready to be used if, for example, wide counterfeiting of the current series suddenly happened. When the Swiss National Bank decided to develop new security features and to abandon the concept of a reserve series, the details of the seventh series were released and the printed notes were destroyed.[60] The current, eighth series of banknotes was designed by Jörg Zintzmeyer around the theme of the arts and released starting in 1995. In addition to its new vertical design, this series was different from the previous one on several counts. Probably the most important difference from a practical point of view was that the seldom-used 500-franc note was replaced by a new 200-franc note; this new note has indeed proved more successful than the old 500-franc note.[note 5] The base colours of the new notes were kept similar to the old ones, except that the 20-franc note was changed from blue to red to prevent a frequent confusion with the 100-franc note, and that the 10-franc note was changed from red to yellow. The size of the notes was changed as well, with all notes from the eighth series having the same height (74 mm), while the widths were changed as well, still increasing with the value of the notes. The new series contains many more security features than the previous one;[61] many of them are now visibly displayed and have been widely advertised, in contrast with the previous series for which most of the features were kept secret.

| Image | Value | Dimensions | Main colour | Obverse | Date of issue | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Reverse | ||||||

|

|

10 francs | 126 × 74 mm | Yellow | Le Corbusier | 8 April 1997 | |

|

|

20 francs | 137 × 74 mm | Red | Arthur Honegger | 1 October 1996 | |

|

|

50 francs | 148 × 74 mm | Green | Sophie Taeuber-Arp | 3 October 1995 | |

|

|

100 francs | 159 × 74 mm | Blue | Alberto Giacometti | 1 October 1998 | |

|

|

200 francs | 170 × 74 mm | Brown | Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz | 1 October 1997 | Replaced the 500-franc banknote in the previous series |

|

|

1000 francs | 181 × 74 mm | Purple | Jacob Burckhardt | 1 April 1998 | |

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||

All banknotes are quadrilingual, displaying all information in the four national languages. The banknotes depicting a Germanophone person have German and Romansch on the same side as the picture, whereas banknotes depicting a Francophone or an Italophone person have French and Italian on the same side as the picture. The reverse has the other two languages.

When the fifth series lost its validity at the end of April 2000, the banknotes that had not been exchanged represented a total value of 244.3 million Swiss francs; in accordance with Swiss law, this amount was transferred to the Swiss Fund for Emergency Losses in the Case of Non-insurable Natural Disasters.[63]

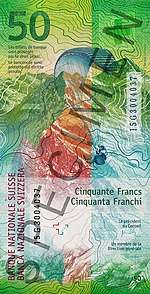

- Ninth (current) series of Swiss banknotes

10 francs, front

10 francs, front 10 francs, back

10 francs, back 20 francs, front

20 francs, front 20 francs, back

20 francs, back 50 francs, front

50 francs, front 50 francs, back

50 francs, back 100 francs, front

100 francs, front 100 francs, back

100 francs, back 200 francs, front

200 francs, front 200 francs, back

200 francs, back 1000 francs, front

1000 francs, front 1000 francs, back

1000 francs, back

In February 2005, a competition was announced for the design of the ninth series, then planned to be released around 2010 on the theme "Switzerland open to the world". The results were announced in November 2005. The National Bank selected the designs of Swiss graphic designer Manuela Pfrunder as the basis of the new series. The first denomination to be issued was the 50-franc note on 12 April 2016. It was followed by the 20-franc note (17 May 2017), the 10-franc note (18 October 2017), the 200-franc note (15 August 2018), the 1000-franc note (5 March 2019) and the 100-franc note (12 September 2019). All banknotes from the eighth series will remain valid until further notice.

Circulation

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code (symbol) | % of daily trades (bought or sold) (April 2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | USD (US$) | 88.3% | |

2 | EUR (€) | 32.3% | |

3 | JPY (¥) | 16.8% | |

4 | GBP (£) | 12.8% | |

5 | AUD (A$) | 6.8% | |

6 | CAD (C$) | 5.0% | |

7 | CHF (CHF) | 5.0% | |

8 | CNY (元) | 4.3% | |

9 | HKD (HK$) | 3.5% | |

10 | NZD (NZ$) | 2.1% | |

11 | SEK (kr) | 2.0% | |

12 | KRW (₩) | 2.0% | |

13 | SGD (S$) | 1.8% | |

14 | NOK (kr) | 1.8% | |

15 | MXN ($) | 1.7% | |

16 | INR (₹) | 1.7% | |

17 | RUB (₽) | 1.1% | |

18 | ZAR (R) | 1.1% | |

19 | TRY (₺) | 1.1% | |

20 | BRL (R$) | 1.1% | |

21 | TWD (NT$) | 0.9% | |

22 | DKK (kr) | 0.6% | |

23 | PLN (zł) | 0.6% | |

24 | THB (฿) | 0.5% | |

25 | IDR (Rp) | 0.4% | |

26 | HUF (Ft) | 0.4% | |

27 | CZK (Kč) | 0.4% | |

28 | ILS (₪) | 0.3% | |

29 | CLP (CLP$) | 0.3% | |

30 | PHP (₱) | 0.3% | |

31 | AED (د.إ) | 0.2% | |

32 | COP (COL$) | 0.2% | |

33 | SAR (﷼) | 0.2% | |

34 | MYR (RM) | 0.1% | |

35 | RON (L) | 0.1% | |

| Other | 2.2% | ||

| Total[note 6] | 200.0% | ||

The Swiss franc is the currency and legal tender of Switzerland and Liechtenstein and also legal tender in the Italian exclave of Campione d'Italia. Although not formally legal tender in the German exclave of Büsingen am Hochrhein (the sole legal currency is the euro), it is in wide daily use there; with many prices quoted in Swiss francs. The Swiss franc is the only version of the franc still issued in Europe.

As of March 2010, the total value of released Swiss coins and banknotes was 49.6640 billion Swiss francs.[65]

| Coins | 10 francs | 20 francs | 50 francs | 100 francs | 200 francs | 500 francs | 1000 francs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,695.4 | 656.7 | 1,416.7 | 1,963.0 | 8,337.4 | 6,828.0 | 129.9 | 27,637.1 | 49,664.0 |

Combinations of up to 100 circulating Swiss coins (not including special or commemorative coins) are legal tender; banknotes are legal tender for any amount.[66]

Current exchange rates

| Current CHF exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From fxtop.com: | AUD CAD EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

See also

- Banking in Switzerland

- Economy of Switzerland

- Hard currency

- Iraqi Swiss dinar, a common name for the old Iraqi currency but not related to Swiss currency.

- Liechtenstein franc

- Gold standard

- List of currencies in Europe

Notes

- Can be pronounced (and written) differently among different regions.

- Swiss franc is the official currency and Euro is widely accepted.

- Swiss franc is widely accepted, although Euro is officially used.

- 150 Years of Swiss coinage.

- The global value of those 200-franc notes in circulation in 2000 (5.1200 billion francs) was larger than the value of the 500-franc notes in 1996 (3.9123 billion), even when these figures are corrected for the global increase in total value of Swiss banknotes in circulation (+9%). Figures from the Monthly Statistical Bulletin of the Swiss National Bank, January 2006, Op cit.

- The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the U.S. Dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the Euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

References

- "Art. 1 Amtliche Bezeichnungen und Abkürzungen/Dénominations officielles et abréviations/Denominazioni ufficiali e abbreviazioni SR/RS 941.101 Münzverordnung/Ordonnance sur la monnaie/Ordinanza sulle monete, 12 April 2000 (MünzV/O sur la monnaie/OMon)" (federal act) (in German, French, and Italian). Berne, Switzerland: Federal Council. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "Schreibweisungen" (PDF) (official site) (in German). Berne, Switzerland: Federal Chancellery. 24 August 2015. pp. 86/87. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- "Instructions de la Chancellerie fédérale sur la présentation des textes officiels en français" (PDF) (official site) (in French). Berne, Switzerland: Federal Chancellery. 27 May 2016. p. 3. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- "Istruzioni della Cancelleria federale per la redazione dei testi ufficiali in italiano" (PDF) (official site) (in Italian). Berne, Switzerland: Federal Chancellery. 27 February 2006. p. 29. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- "Style Guides for English-language translators" (PDF) (official site). Berne, Switzerland: Federal Chancellery. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- LaLiberté.ch Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, (in French) La Liberté, 9 January 2009, La fabuleuse histoire du franc suisse.

- WALCHER, S. (8 August 1840). "Livre de poche du Voyageur en Suisse faisant connâitre toutes les curiosités ... de la Suisse d'un partie de la Savoye et de la Valtelline, etc" – via Google Books.

- "Loi du 25 juin 1798". Bulletin des loix et décrets du Corps législatif de la République helvétique (in French). Henri Emanuel Vincent. 1798.

- Otto Paul Wenger, pp. 49–50.

- Gold.org Archived 18 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Table of currency devaluations in the United States and Europe following the devaluation of the pound in 1931, in Monetary History of Gold: volume 3 — After the Gold Standard (from http://www.gold.org/government_affairs/gold_as_a_monetary_asset/historical_records_back_to_the_17th_century/after_the_gold_standard/)

- Gold.org Archived 22 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Declaration of the Swiss Government, through the Federal Finance and Customs Department, and the National Bank of Switzerland regarding the purchase and sale of gold, in Monetary History of Gold: volume 3 — After the Gold Standard

- "Swiss Narrowly Vote to Drop Gold Standard". The New York Times. Associated Press. 19 April 1999. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Federal Law on Currency and Legal Tender to enter into force on 1 May 2000" (Press release). Efd.admin.ch. 12 April 2000. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "Speech by Philipp M. Hildebrand, Member of the Governing Board, Swiss National Bank" (PDF). Iie.com. 5 May 2005.

- Bosley, Catherine (30 November 2014). "Swiss gold initiative vote". Bloomberg.

- Bennett, Allison; Saraiva, Catarina (25 June 2001). "Swiss Franc Climbs to Record High on Greece Crisis". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Meier, Simone (10 August 2011). "SNB Steps Up Franc Fight to Counter 'Massive Overvaluation". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "Francly wrong". The Economist. Economist.com. 10 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Mijuk, Goran (31 August 2011). "Swiss Short-Term Debt Yields in Negative Territory". The Wall Street Journal. Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- "Swiss Franc(CHF) To Euro(EUR) on 05 Aug 2011 (05/08/2011) Currency Exchange - Foreign Currency Exchange Rates and Currency Converter Calculator". chf.fx-exchange.com.

- "Swiss National Bank acts to weaken strong franc". BBC News. BBC.com. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Wille, Klaus (6 September 2011). "Swiss Pledge Unlimited Currency Purchases". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg News. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "Swiss Central Bank In Move To Weaken Franc". Sky News. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Weisenthal, Joe (6 September 2011). "THEY DID IT: Swiss National Bank Makes Epic Intervention Move, Sending The Swiss Franc Plunging". Business Insider. Businessinsider.com. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Wearden, Graeme (6 September 2011). "Currency traders stunned by SNB intervention". The Guardian. London: theguardian.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Bennett, Allison (6 September 2011). "Franc Plunges Most Ever Versus Euro". Bloomberg.com.

- Thomasson, Emma (6 September 2011). "Swiss draw line in the sand to cap runaway franc". Reuters.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- "Markets Reel after Swiss Franc Shock". primepair.com. 16 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015.

- "Franc Rises vs. Euro, Breaks Ceiling". Topforexnews.com. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "Swiss central bank imposes negative interest rates". Yahoo Finance. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- "'Francogeddon': Swiss central bank stuns market with policy U-turn". Sydney Morning Herald. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "'Francogeddon' as Swiss franc ends euro cap". BBC News. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "'Francogeddon': New Zealand foreign exchange broker shuts after Swiss national bank scraps currency cap". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Swiss queue round the block to change currency as 'Francogeddon' continues". London Evening Standard. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Swiss franc soars as Switzerland abandons euro cap". BBC News. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Inman, Phillip (15 January 2015). "Markets in turmoil as Switzerland removes currency cap". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

Currency and stock markets were thrown into turmoil across Europe

- Wong, Andrea; Evans, Rachel (16 January 2015). "Swiss Franc Roils Markets as SNB Abandons Cap". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Alpari UK denies acquisition by FXCM, talks continuing - LeapRate Exclusive". 18 January 2015.

- "Alpari UK currency broker folds over Swiss franc turmoil". BBC News. 16 January 2015.

- Kilgore, Tomi. "Leucadia to provide FXCM with $300 million loan".

- "Swiss franc fallout takes more casualties". FT.com. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "New Zealand forex broker shuts after Swiss franc move". Agence France-Presse.

- Richard Barley (16 January 2015). "Swiss Tarnish Central Banks". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Bianca Hartge-Hazelman (21 January 2015). "Central banks 'have lost credibility'". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- (de) Jürg Richter et Ruedi Kunzmann, Neuer HMZ-Katalog, tome 2 : Die Münzen der Schweiz und Liechtensteins 15./16 Jahrhundert bis Gegenwart, (ISBN 3-86646-504-1)

- SwissMint.ch Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Mintage figures for Swiss coins as of 1850, status in January 2007.

- SwissMint.ch Frequently Asked Questions (D-27). Last accessed 5 January 2017.

- SwissMint.ch Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Mintage figures for Swiss coins as of 1850, status in January 2007

- SwissMint.ch, 150 Years of Swiss coinage: From silver to cupronickel. Last accessed 2 March 2006. Archived 1 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Visible on the pictures of the Swiss coins

- "Ordonnance sur la monnaie (Order on Currency)" (PDF) (in French). Government of Switzerland. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- SwissMint.ch, Circulation coins: Technical data. Last accessed 30 October 2006. Archived 5 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Cuhaj 2010, pp. 1135–36.

- Cuhaj 2010, p. 1137.

- Cuhaj 2010, pp. 1138.

- "Sixth banknote series, 1976". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Blackstone, Brian (20 October 2017). "Switzerland's Old-Money Problem: One Billion in Expiring Francs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "Questions and answers on banknotes - What does 'the SNB is recalling banknotes from circulation' actually mean?". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "Seventh banknote series, 1984". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- An overview of the security features Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Swiss National Bank. Last accessed 20 September 2012.

- "Eighth banknote series, 1995". Swiss National Bank. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "National Bank remits Sfr 244,3 million to the Fund for Emergency Losses" (PDF) (Press release). Swiss National Bank. 4 May 2000. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2019" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 16 September 2019. p. 10. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Swiss National Bank Monthly Statistical Bulletin" (PDF) (Press release). Bern: Swiss National Bank. February 2010. p. A2: Banknotes and coins in circulation. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Art. 3 of the Swiss law on Monetary Unit and means of payment. Admin.ch (German), Admin.ch (French) and Admin.ch (Italian) versions.

Further reading

- Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2010). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money General Issues (1368-1960) (13th ed.). Krause. ISBN 978-1-4402-1293-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Lescaze, Bernard (1999). Une monnaie pour la Suisse. Hurter. ISBN 2-940031-83-5.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- Rivaz, Michel de (1997). The Swiss Banknote: 1907–1997. Genoud. ISBN 2-88100-080-0.

- Swissmint.ch, 150 Years of Swiss coinage: A brief historical discourse. Last accessed 2 March 2006.

- Swissmint.ch; Prägungen von Schweizer Münzen ab 1850 — Frappes des pièces de monnaie suisses à partir de 1850, 2010.

- Wartenwiler, H. U. (2006). Swiss Coin Catalog 1798–2005. ISBN 3-905712-00-8

- Wenger, Otto Paul (1978). Introduction à la numismatique, Cahier du Crédit Suisse, August 1978. (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Swiss franc. |

- (in German) CashFollow.ch, Swiss Franc Tracker

- (in German) Schweizer-Franken.ch, Information about the Swiss Franc

- (in English) Switzerland Banknotes, Swiss Franc: Banknote Catalog from 1907

- - historical exchange rates of USD/CHF (from the year 1800 to present time).

- - historical chart of USD/CHF (from the year 1800 to present time).

- (in English and German) The Banknotes of Switzerland

.svg.png)