Proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) characterizes electoral systems in which divisions in an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body.[1] If n% of the electorate support a particular political party or set of candidates as their favorite, then roughly n% of seats will be won by that party or those candidates.[2] The essence of such systems is that all votes contribute to the result—not just a plurality, or a bare majority. The most prevalent forms of proportional representation all require the use of multiple-member voting districts (also called super-districts), as it is not possible to fill a single seat in a proportional manner. In fact, PR systems that achieve the highest levels of proportionality tend to include districts with large numbers of seats.[3]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

Plurality/majoritarian

|

|

|

Other systems and related theory |

|

|

The most widely used families of PR electoral systems are party-list PR, the single transferable vote (STV), and mixed-member proportional representation (MMP).[4]

With party list PR, political parties define candidate lists and voters vote for a list. The relative vote for each list determines how many candidates from each list are actually elected. Lists can be "closed" or "open"; open lists allow voters to indicate individual candidate preferences and vote for independent candidates. Voting districts can be small (as few as three seats in some districts in Chile or Ireland) or as large as a province or an entire nation.

The single transferable vote uses multiple-member districts, with voters casting only one vote each but ranking individual candidates in order of preference (by providing back-up preferences). During the count, as candidates are elected or eliminated, surplus or discarded votes that would otherwise be wasted are transferred to other candidates according to the preferences, forming consensus groups that elect surviving candidates. STV enables voters to vote across party lines, to choose the most preferred of a party's candidates and vote for independent candidates, knowing that if the candidate is not elected his/her vote will likely not be wasted if the voter marks back-up preferences on the ballot.

Mixed member proportional representation (MMP), also called the additional member system (AMS), is a two-tier mixed electoral system combining local non-proportional plurality/majoritarian elections and a compensatory regional or national party list PR election. Voters typically have two votes, one for their single-member district and one for the party list, the party list vote determining the balance of the parties in the elected body.[3][5]

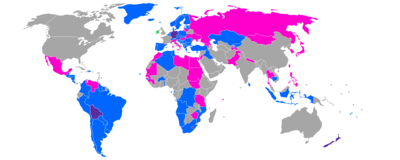

According to the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network,[6] some form of proportional representation is used for national lower house elections in 94 countries. Party list PR, being used in 85 countries, is the most widely used. MMP is used in seven lower houses. STV, despite long being advocated by political scientists,[3]:71 is used in only two: Ireland, since independence in 1922,[7] and Malta, since 1921.[8] STV is also used in the Australian Senate, and can be used for nonpartisan elections such as the city council of Cambridge MA.[9]

As with all electoral systems, both widely accepted and sharply opposing claims are made about the advantages and disadvantages of PR.[10][11]

Advantages and disadvantages

The case for proportional representation was made by John Stuart Mill in his 1861 essay Considerations on Representative Government:

In a representative body actually deliberating, the minority must of course be overruled; and in an equal democracy, the majority of the people, through their representatives, will outvote and prevail over the minority and their representatives. But does it follow that the minority should have no representatives at all? ... Is it necessary that the minority should not even be heard? Nothing but habit and old association can reconcile any reasonable being to the needless injustice. In a really equal democracy, every or any section would be represented, not disproportionately, but proportionately. A majority of the electors would always have a majority of the representatives, but a minority of the electors would always have a minority of the representatives. Man for man, they would be as fully represented as the majority. Unless they are, there is not equal government ... there is a part whose fair and equal share of influence in the representation is withheld from them, contrary to all just government, but, above all, contrary to the principle of democracy, which professes equality as its very root and foundation.[1]

Many academic political theorists agree with Mill,[12] that in a representative democracy the representatives should represent all substantial segments of society, a goal impossible to achieve under First past the post.

Fairness

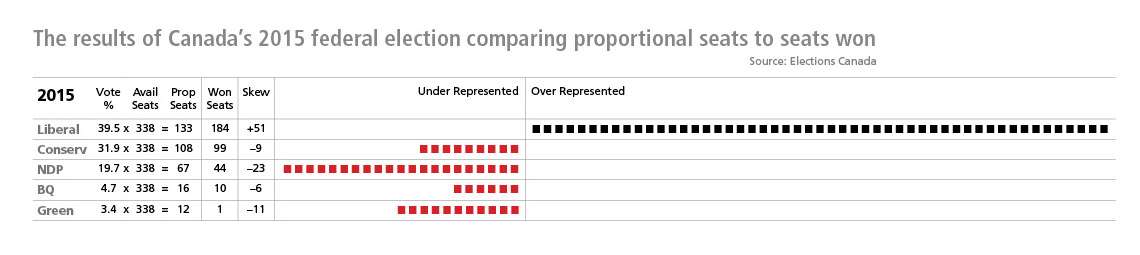

PR tries to resolve the unfairness of majoritarian and plurality voting systems where the largest parties receive an "unfair" "seat bonus" and smaller parties are disadvantaged and are always under-represented and on occasion winning no representation at all (Duverger's law).[13][14]:6–7 An established party in UK elections can win majority control of the House of Commons with as little as 35% of votes (2005 UK general election). In certain Canadian elections, majority governments have been formed by parties with the support of under 40% of votes cast (2011 Canadian election, 2015 Canadian election). If turnout levels in the electorate are less than 60%, such outcomes allow a party to form a majority government by convincing as few as one quarter of the electorate to vote for it. In the 2005 UK election, for example, the Labour Party under Tony Blair won a comfortable parliamentary majority with the votes of only 21.6% of the total electorate.[15]:3 Such misrepresentation has been criticized as "no longer a question of 'fairness' but of elementary rights of citizens".[16]:22 Note intermediate PR systems with a high electoral threshold, or other features that reduce proportionality, are not necessarily much fairer: in the 2002 Turkish general election, using an open list system with a 10% threshold, 46% of votes were wasted.[3]:83

Plurality/majoritarian systems also benefit regional parties that win many seats in the region where they have a strong following but have little support nationally, while other parties with national support that is not concentrated in specific districts, like the Greens, win few or no seats. An example is the Bloc Québécois in Canada that won 52 seats in the 1993 federal election, all in Quebec, on 13.5% of the national vote, while the Progressive Conservatives collapsed to two seats on 16% spread nationally. The Conservative party although strong nationally had had very strong regional support in the West but in this election its supporters in the West turned to the Reform party, which won most of its seats west of Saskatchewan and none east of Manitoba.[14][17] Similarly, in the 2015 UK General Election, the Scottish National Party gained 56 seats, all in Scotland, with a 4.7% share of the national vote while the UK Independence Party, with 12.6%, gained only a single seat.[18]

Election of minor parties

The use of multiple-member districts enables a greater variety of candidates to be elected. The more representatives per district and the lower the percentage of votes required for election, the more minor parties can gain representation. It has been argued that in emerging democracies, inclusion of minorities in the legislature can be essential for social stability and to consolidate the democratic process.[3]:58

Critics, on the other hand, claim this can give extreme parties a foothold in parliament, sometimes cited as a cause for the collapse of the Weimar government. With very low thresholds, very small parties can act as "king-makers",[19] holding larger parties to ransom during coalition discussions. The example of Israel is often quoted,[3]:59 but these problems can be limited, as in the modern German Bundestag, by the introduction of higher threshold limits for a party to gain parliamentary representation (which in turn increases the number of wasted votes).

Another criticism is that the dominant parties in plurality/majoritarian systems, often looked on as "coalitions" or as "broad churches",[20] can fragment under PR as the election of candidates from smaller groups becomes possible. Israel, again, and Brazil and Italy are examples.[3]:59,89 However, research shows, in general, there is only a small increase in the number of parties in parliament (although small parties have larger representation) under PR.[21]

Open list systems and STV, the only prominent PR system which does not require political parties,[22] enable independent candidates to be elected. In Ireland, on average, about six independent candidates have been elected each parliament.[23] This can lead to a situation that forming a Parliamentary majority requires support of one or more of these independent representatives. In some cases these independents have positions that are closely aligned with the governing party and it hardly matters. The Irish Government formed after the 2016 election even include independent representatives in the cabinet of a minority government. In others, the electoral platform is entirely local and addressing this is a price for support.

Coalitions

The election of smaller parties gives rise to one of the principal objections to PR systems, that they almost always result in coalition governments.[3]:59[12]

Supporters of PR see coalitions as an advantage, forcing compromise between parties to form a coalition at the centre of the political spectrum, and so leading to continuity and stability. Opponents counter that with many policies compromise is not possible. Neither can many policies be easily positioned on the left-right spectrum (for example, the environment). So policies are horse-traded during coalition formation, with the consequence that voters have no way of knowing which policies will be pursued by the government they elect; voters have less influence on governments. Also, coalitions do not necessarily form at the centre, and small parties can have excessive influence, supplying a coalition with a majority only on condition that a policy or policies favoured by few voters is/are adopted. Most importantly, the ability of voters to vote a party in disfavour out of power is curtailed.[12]

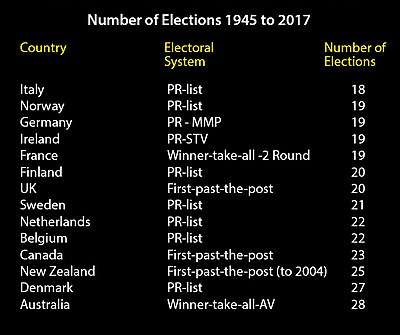

All these disadvantages, the PR opponents contend, are avoided by two-party plurality systems. Coalitions are rare; the two dominant parties necessarily compete at the centre for votes, so that governments are more reliably moderate; the strong opposition necessary for proper scrutiny of government is assured; and governments remain sensitive to public sentiment because they can be, and are, regularly voted out of power.[12] However, this is not necessarily so; a two-party system can result in a "drift to extremes", hollowing out the centre,[24] or, at least, in one party drifting to an extreme.[25] The opponents of PR also contend that coalition governments created under PR are less stable, and elections are more frequent. Italy is an often-cited example with many governments composed of many different coalition partners. However, Italy is unusual in that both its houses can make a government fall, whereas other PR nations have either just one house or have one of their two houses be the core body supporting a government. Italy's mix of FPTP and PR since 1993 also makes for a complicated setup, so Italy is not an appropriate candidate for measuring the stability of PR.

Voter participation

Plurality systems usually result in single-party-majority government because generally fewer parties are elected in large numbers under FPTP compared to PR, and FPTP compresses politics to little more than two-party contests, with relatively few votes in a few of the most finely balanced districts, the "swing seats", able to swing majority control in the house. Incumbents in less evenly divided districts are invulnerable to slight swings of political mood. In the UK, for example, about half the constituencies have always elected the same party since 1945;[26] in the 2012 US House elections 45 districts (10% of all districts) were uncontested by one of the two dominant parties.[27] Voters who know their preferred candidate will not win have little incentive to vote, and even if they do their votes have no effect, it is "wasted", although they would be counted in the popular vote calculation.[3]:10

With PR, there are no "swing seats", most votes contribute to the election of a candidate so parties need to campaign in all districts, not just those where their support is strongest or where they perceive most advantage. This fact in turn encourages parties to be more responsive to voters, producing a more "balanced" ticket by nominating more women and minority candidates.[14] On average about 8% more women are elected.[21]

Since most votes count, there are fewer "wasted votes", so voters, aware that their vote can make a difference, are more likely to make the effort to vote, and less likely to vote tactically. Compared to countries with plurality electoral systems, voter turnout improves and the population is more involved in the political process.[3][14][21] However some experts argue that transitioning from plurality to PR only increases voter turnout in geographical areas associated with safe seats under the plurality system; turnout may decrease in areas formerly associated with swing seats.[28]

Gerrymandering

To ensure approximately equal representation, plurality systems are dependent on the drawing of boundaries of their single-member districts, a process vulnerable to political interference (gerrymandering). To compound the problem, boundaries have to be periodically re-drawn to accommodate population changes. Even apolitically drawn boundaries can unintentionally produce the effect of gerrymandering, reflecting naturally occurring concentrations.[29]:65

PR systems with their multiple-member districts are less prone to this – research suggests five-seat districts or larger are immune to gerrymandering.[29]:66

Equality of size of multiple-member districts is not important (the number of seats can vary) so districts can be aligned with historical territories of varying sizes such as cities, counties, states, or provinces. Later population changes can be accommodated by simply adjusting the number of representatives elected. For example, Professor Mollison in his 2010 plan for STV for the UK divided the country into 143 districts and then allocated a different number of seats to each district (to equal the existing total of 650) depending on the number of voters in each but with wide ranges (his five-seat districts include one with 327,000 voters and another with 382,000 voters). His district boundaries follow historical county and local authority boundaries, yet he achieves more uniform representation than does the Boundary Commission, the body responsible for balancing the UK's first-past-the-post constituency sizes.[26][30]

Mixed member systems are susceptible to gerrymandering for the local seats that remain a part of such systems. Under parallel voting, a semi-proportional system, there is no compensation for the effects that such gerrymandering might have. Under MMP, the use of compensatory list seats makes gerrymandering less of an issue. However, its effectiveness in this regard depends upon the features of the system, including the size of the regional districts, the relative share of list seats in the total, and opportunities for collusion that might exist. A striking example of how the compensatory mechanism can be undermined can be seen in the 2014 Hungarian parliamentary election, where the leading party, Fidesz, combined gerrymandering and decoy lists, which resulted in a two-thirds parliamentary majority from a 45% vote.[31][32] This illustrates how certain implementations of MMP can produce moderately proportional outcomes, similar to parallel voting.

Link between constituent and representative

It is generally accepted that a particular advantage of plurality electoral systems such as first past the post, or majoritarian electoral systems such as the alternative vote, is the geographic link between representatives and their constituents.[3]:36[33]:65[16]:21 A notable disadvantage of PR is that, as its multiple-member districts are made larger, this link is weakened.[3]:82 In party list PR systems without delineated districts, such as the Netherlands and Israel, the geographic link between representatives and their constituents is considered weak, but has shown to play a role for some parties. Yet with relatively small multiple-member districts, in particular with STV, there are counter-arguments: about 90% of voters can consult a representative they voted for, someone whom they might think more sympathetic to their problem. In such cases it is sometimes argued that constituents and representatives have a closer link;[26][29]:212 constituents have a choice of representative so they can consult one with particular expertise in the topic at issue.[29]:212[34] With multiple-member districts, prominent candidates have more opportunity to be elected in their home constituencies, which they know and can represent authentically. There is less likely to be a strong incentive to parachute them into constituencies in which they are strangers and thus less than ideal representatives.[35]:248–250 Mixed-member PR systems incorporate single-member districts to preserve the link between constituents and representatives.[3]:95 However, because up to half the parliamentary seats are list rather than district seats, the districts are necessarily up to twice as large as with a plurality/majoritarian system where all representatives serve single-member districts.[16]:32

An interesting case occurred in the Netherlands, when "out of the blue" a Party for the Elderly gained six seats. The other parties had not paid attention, but this made them aware. With the next election, the Party of the Elderly was gone, because the established parties had started to listen to the elderly. Today, a party for older folks, 50PLUS, has established itself firmly in the Netherlands. This can be seen as an example how geography in itself may not be a good enough reason to establish voting results around it and overturn all other particulars of the voting population. In a sense, voting in districts restricts the voters to a specific geography. Proportional voting follows the exact outcome of all the votes.[36]

Attributes of PR systems

District magnitude

Academics agree that the most important influence on proportionality is an electoral district's magnitude, the number of representatives elected from the district. Proportionality improves as the magnitude increases.[3] Some scholars recommend voting districts of roughly four to eight seats, which are considered small relative to PR systems in general.[37]

At one extreme, the binomial electoral system used in Chile between 1989 and 2013,[38] a nominally proportional open-list system, features two-member districts. As this system can be expected to result in the election of one candidate from each of the two dominant political blocks in most districts, it is not generally considered proportional.[3]:79

At the other extreme, where the district encompasses the entire country (and with a low minimum threshold, highly proportionate representation of political parties can result), parties gain by broadening their appeal by nominating more minority and women candidates.[3]:83

After the introduction of STV in Ireland in 1921 district magnitudes slowly diminished as more and more three-member constituencies were defined, benefiting the dominant Fianna Fáil, until 1979 when an independent boundary commission was established reversing the trend.[39] In 2010, a parliamentary constitutional committee recommended a minimum magnitude of four.[40] Nonetheless, despite relatively low magnitudes Ireland has generally experienced highly proportional results.[3]:73

In the FairVote plan for STV (which FairVote calls choice voting) for the US House of Representatives, three- to five-member super-districts are proposed.[41]

In Professor Mollison's plan for STV in the UK, four- and five-member districts are mostly used, with three and six seat districts used as necessary to fit existing boundaries, and even two and single member districts used where geography dictates.[26]

Electoral threshold

The electoral threshold is the minimum vote required to win a seat. The lower the threshold, the higher the proportion of votes contributing to the election of representatives and the lower the proportion of votes wasted.[3]

All electoral systems have thresholds, either formally defined or as a mathematical consequence of the parameters of the election.[3]:83

A formal threshold usually requires parties to win a certain percentage of the vote in order to be awarded seats from the party lists. In Germany and New Zealand (both MMP), the threshold is 5% of the national vote but the threshold is not applied to parties that win a minimum number of constituency seats (three in Germany, one in New Zealand). Turkey defines a threshold of 10%, the Netherlands 0.67%.[3] Israel has raised its threshold from 1% (before 1992) to 1.5% (up to 2004), 2% (in 2006) and 3.25% in 2014.[42]

In STV elections, winning the quota (ballots/(seats+1)) of first preference votes assures election. However, well regarded candidates who attract good second (and third, etc.) preference support can hope to win election with only half the quota of first preference votes. Thus, in a six-seat district the effective threshold would be 7.14% of first preference votes (100/(6+1)/2).[26] The need to attract second preferences tends to promote consensus and disadvantage extremes.

Party magnitude

Party magnitude is the number of candidates elected from one party in one district. As party magnitude increases a more balanced ticket will be more successful encouraging parties to nominate women and minority candidates for election.[43]

But under STV, nominating too many candidates can be counter-productive, splitting the first-preference votes and allowing the candidates to be eliminated before receiving transferred votes from other parties. An example of this was identified in a ward in the 2007 Scottish local elections where Labour, putting up three candidates, won only one seat while they might have won two had one of their voters' preferred candidates not stood.[26] The same effect may have contributed to the collapse of Fianna Fáil in the 2011 Irish general election.[44]

Potential lack of balance in Presidential systems

In a presidential system, the president is chosen independently from the parliament. As a consequence, it is possible to have a divided government where a parliament and president have opposing views and may want to balance each other influence. However, the proportional system favors government of coalitions of many smaller parties that require compromising and negotiating topics[45]. As a consequence, these coalitions might have difficulties presenting a united front to counter presidential influence, leading to an lack of balance between these two powers. With a proportionally elected House, a President may strong-arm certain political issues

This issue does not happen in Parliamentary system, where the prime-minister is elected indirectly, by the parliament itself. As a consequence a divided government is impossible. Even if the political views change with time and the prime-minister lose its support from parliament, it can be replaced with a motion of no confidence. Effectively, both measures make it impossible to create a divided government.

Others

Other aspects of PR can influence proportionality such as the size of the elected body, the choice of open or closed lists, ballot design, and vote counting methods.

Measuring proportionality

In many contexts, it is desired to evaluate how well do the awarded seat shares approximate proportionality. However, only exact proportionality has a single unambiguous definition. A seat allocation is proportional only if the seat shares are equal to the vote shares. If this condition is not met, the seat allocation is disproportional. Consequently, an index of proportionality will only take two values, one if the allocation is proportional and the other if it is not.

In practice, it may be more interesting to examine the degree to which the number of seats won by each party differs from that of a perfectly proportional outcome. In other words, how disproportional is the seat allocation. Unlike exact proportionality, disproportionality does not have a single unambiguous definition. Any index that takes the value of zero if the seat allocation is proportional and a larger value if it is not measures disproportionality. A number of such indexes has been proposed, including the Loosemore–Hanby index, the Gallagher Index, and the Sainte-Laguë Index.[46] If there are some values of seat shares and vote shares for which two disproportionality indexes disagree, then the indexes measure different concepts of disproportionality. Some disproportionality concepts have been mapped to social welfare functions.[47]

Disproportionality indexes are sometimes used to evaluate existing and proposed electoral systems. For example, the Canadian Parliament's 2016 Special Committee on Electoral Reform recommended that a system be designed to achieve "a Gallagher score of 5 or less". This indicated a much lower degree of disproportionality than observed in the 2015 Canadian election under first-past-the-post voting, where the Gallagher index was 12.[11]

The Loosemore-Hanby index is calculated by subtracting each party's vote share from its seat share, adding up the absolute values (ignoring any negative signs), and dividing by two.[48]:4–6

The Gallagher index is similar, but involves squaring the difference between each party's vote share and seat share, and taking the square root of the sum.

With the Sainte-Laguë index, the discrepancy between a party's vote share and seat share is measured relative to its vote share.

None of these indexes (Loosemore-Hanby, Gallagher, Sainte-Laguë) fully support ranked voting.[49][50]

PR electoral systems

Party list PR

Party list proportional representation is an electoral system in which seats are first allocated to parties based on vote share, and then assigned to party-affiliated candidates on the parties' electoral lists. This system is used in many countries, including Finland (open list), Latvia (open list), Sweden (open list), Israel (national closed list), Brazil (open list), Nepal (closed list) as adopted in 2008 in first CA election, the Netherlands (open list), Russia (closed list), South Africa (closed list), Democratic Republic of the Congo (open list), and Ukraine (open list). For elections to the European Parliament, most member states use open lists; but most large EU countries use closed lists, so that the majority of EP seats are distributed by those.[51] Local lists were used to elect the Italian Senate during the second half of the 20th century.

Closed list PR

In closed list systems, each party lists its candidates according to the party's candidate selection process. This sets the order of candidates on the list and thus, in effect, their probability of being elected. The first candidate on a list, for example, will get the first seat that party wins. Each voter casts a vote for a list of candidates. Voters, therefore, do not have the option to express their preferences at the ballot as to which of a party's candidates are elected into office.[52][53] A party is allocated seats in proportion to the number of votes it receives.[54]

There is an intermediate system in Uruguay, where each party presents several closed lists, each representing a faction. Seats are distributed between parties according to the number of votes, and then between the factions within each party.

Open list PR

In an open list, voters may vote, depending on the model, for one person, or for two, or indicate their order of preference within the list. These votes sometimes rearrange the order of names on the party's list and thus which of its candidates are elected. Nevertheless, the number of candidates elected from the list is determined by the number of votes the list receives.

Local list PR

In a local list system, parties divide their candidates in single member-like constituencies, which are ranked inside each general party list depending by their percentages. This method allows electors to judge every single candidate as in a FPTP system.

Two-tier party list systems

Some party list proportional systems with open lists use a two-tier compensatory system, as in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In Denmark, for example, the country is divided into ten multiple-member voting districts arranged in three regions, electing 135 representatives. In addition, 40 compensatory seats are elected. Voters have one vote which can be cast for an individual candidate or for a party list on the district ballot. To determine district winners, candidates are apportioned their share of their party's district list vote plus their individual votes. The compensatory seats are apportioned to the regions according to the party votes aggregated nationally, and then to the districts where the compensatory representatives are determined. In the 2007 general election, the district magnitudes, including compensatory representatives, varied between 14 and 28. The basic design of the system has remained unchanged since its introduction in 1920.[55][56][57]

Single transferable vote

The single transferable vote (STV), also called choice voting,[58][9] is a ranked system: voters rank candidates in order of preference. Voting districts usually elect three to seven representatives. The count is cyclic, electing or eliminating candidates and transferring votes until all seats are filled. A candidate is elected whose tally reaches a quota, the minimum vote that guarantees election. The candidate's surplus votes (those in excess of the quota) are transferred to other candidates at a fraction of their value proportionate to the surplus, according to the votes' preferences. If no candidates reach the quota, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, those votes being transferred to their next preference at full value, and the count continues. There are many methods for transferring votes. Some early, manual, methods transferred surplus votes according to a randomly selected sample, or transferred only a "batch" of the surplus, other more recent methods transfer all votes at a fraction of their value (the surplus divided by the candidate's tally) but may need the use of a computer. Some methods may not produce exactly the same result when the count is repeated. There are also different ways of treating transfers to already elected or eliminated candidates, and these, too, can require a computer.[59][60]

In effect, the method produces groups of voters of equal size that reflect the diversity of the electorate, each group having a representative the group voted for. Some 90% of voters have a representative to whom they gave their first preference. Voters can choose candidates using any criteria they wish, the proportionality is implicit.[26] Political parties are not necessary; all other prominent PR electoral systems presume that parties reflect voters wishes, which many believe gives power to parties.[59] STV satisfies the electoral system criterion proportionality for solid coalitions – a solid coalition for a set of candidates is the group of voters that rank all those candidates above all others – and is therefore considered a system of proportional representation.[59] However, the small district magnitude used in STV elections has been criticized as impairing proportionality, especially when more parties compete than there are seats available,[12]:50 and STV has, for this reason, sometimes been labelled "quasi proportional".[61]:83 While this may be true when considering districts in isolation, results overall are proportional. In Ireland, with particularly small magnitudes, results are "highly proportional".[3]:73[7] In 1997, the average magnitude was 4.0 but eight parties gained representation, four of them with less than 3% of first preference votes nationally. Six independent candidates also won election.[39] STV has also been described as the most proportional system.[61]:83 The system tends to handicap extreme candidates because, to gain preferences and so improve their chance of election, candidates need to canvass voters beyond their own circle of supporters, and so need to moderate their views.[62][63] Conversely, widely respected candidates can win election with relatively few first preferences by benefitting from strong subordinate preference support.[26]

Australian Senate STV

The term STV in Australia refers to the Senate electoral system, a variant of Hare-Clark characterized by the "above the line" group voting ticket, a party list option. It is used in the Australian upper house, the Senate, most state upper houses, the Tasmanian lower house and the Capital Territory assembly. Due to the number of preferences that are compulsory if a vote for candidates (below-the-line) is to be valid – for the Senate a minimum of 90% of candidates must be scored, in 2013 in New South Wales that meant writing 99 preferences on the ballot[64] – 95% and more of voters use the above-the-line option, making the system, in all but name, a party list system.[65][66][67] Parties determine the order in which candidates are elected and also control transfers to other lists and this has led to anomalies: preference deals between parties, and "micro parties" which rely entirely on these deals. Additionally, independent candidates are unelectable unless they form, or join, a group above-the-line.[68][69] Concerning the development of STV in Australia researchers have observed: "... we see real evidence of the extent to which Australian politicians, particularly at national levels, are prone to fiddle with the electoral system".[61]:86

As a result of a parliamentary commission investigating the 2013 election, from 2016 the system has been considerably reformed (see 2016 Australian federal election), with group voting tickets (GVTs) abolished and voters no longer required to fill all boxes.

Mixed compensatory systems

A mixed compensatory system is an electoral system that is mixed, meaning that it combines a plurality/majority formula with a proportional formula,[70] and that uses the proportional component to compensate for disproportionality caused by the plurality/majority component.[71][72] For example, suppose that a party wins 10 seats based on plurality, but requires 15 seats in total to obtain its proportional share of an elected body. A fully proportional mixed compensatory system would award this party 5 compensatory (PR) seats, raising the party's seat count from 10 to 15. The most prominent mixed compensatory system is mixed member proportional representation (MMP), used in Germany since 1949. In MMP, the seats won by plurality are associated with single-member districts.

Mixed member proportional representation

Mixed member proportional representation (MMP) is a two-tier system that combines a single-district vote, usually first-past-the-post, with a compensatory regional or nationwide party list proportional vote. The system aims to combine the local district representation of FPTP and the proportionality of a national party list system. MMP has the potential to produce proportional or moderately proportional election outcomes, depending on a number of factors such as the ratio of FPTP seats to PR seats, the existence or nonexistence of extra compensatory seats to make up for overhang seats, and electoral thresholds.[73][74][75] It was invented for the German Bundestag after the Second World War and has spread to Lesotho, Bolivia and New Zealand. The system is also used for the Welsh and Scottish assemblies where it is called the additional member system.[5][4]

Voters typically have two votes, one for their district representative and one for the party list. The list vote usually determines how many seats are allocated to each party in parliament. After the district winners have been determined, sufficient candidates from each party list are elected to "top-up" each party to the overall number of parliamentary seats due to it according to the party's overall list vote. Before apportioning list seats, all list votes for parties which failed to reach the threshold are discarded. If eliminated parties lose seats in this manner, then the seat counts for parties that achieved the threshold improve. Also, any direct seats won by independent candidates are subtracted from the parliamentary total used to apportion list seats.[76]

The system has the potential to produce proportional results, but proportionality can be compromised if the ratio of list to district seats is too low, it may then not be possible to completely compensate district seat disproportionality. Another factor can be how overhang seats are handled, district seats that a party wins in excess of the number due to it under the list vote. To achieve proportionality, other parties require "balance seats", increasing the size of parliament by twice the number of overhang seats, but this is not always done. Until recently, Germany increased the size of parliament by the number of overhang seats but did not use the increased size for apportioning list seats. This was changed for the 2013 national election after the constitutional court rejected the previous law, not compensating for overhang seats had resulted in a negative vote weight effect.[77] Lesotho, Scotland and Wales do not increase the size of parliament at all, and, in 2012, a New Zealand parliamentary commission also proposed abandoning compensation for overhang seats, and so fixing the size of parliament. At the same time, it would abolish the single-seat threshold – any such seats would then be overhang seats and would otherwise have increased the size of parliament further – and reduce the electoral threshold from 5% to 4%. Proportionality would not suffer.[3][78]

Dual member proportional representation

Dual member proportional representation (DMP) is a single-vote system that elects two representatives in every district.[79] The first seat in each district is awarded to the candidate who wins a plurality of the votes, similar to first-past-the-post voting. The remaining seats are awarded in a compensatory manner to achieve proportionality across a larger region. DMP employs a formula similar to the "best near-winner" variant of MMP used in the German state of Baden-Württemberg.[80] In Baden-Württemberg, compensatory seats are awarded to candidates who receive high levels of support at the district level compared with other candidates of the same party. DMP differs in that at most one candidate per district is permitted to obtain a compensatory seat. If multiple candidates contesting the same district are slated to receive one of their parties' compensatory seats, the candidate with the highest vote share is elected and the others are eliminated. DMP is similar to STV in that all elected representatives, including those who receive compensatory seats, serve their local districts. Invented in 2013 in the Canadian province of Alberta, DMP received attention on Prince Edward Island where it appeared on a 2016 plebiscite as a potential replacement for FPTP,[81][82] but was eliminated on the third round.[83][84]

Biproportional apportionment

Biproportional apportionment applies a mathematical method (iterative proportional fitting) for the modification of an election result to achieve proportionality. It was proposed for elections by the mathematician Michel Balinski in 1989, and first used by the city of Zurich for its council elections in February 2006, in a modified form called "new Zurich apportionment" (Neue Zürcher Zuteilungsverfahren). Zurich had had to modify its party list PR system after the Swiss Federal Court ruled that its smallest wards, as a result of population changes over many years, unconstitutionally disadvantaged smaller political parties. With biproportional apportionment, the use of open party lists hasn't changed, but the way winning candidates are determined has. The proportion of seats due to each party is calculated according to their overall citywide vote, and then the district winners are adjusted to conform to these proportions. This means that some candidates, who would otherwise have been successful, can be denied seats in favor of initially unsuccessful candidates, in order to improve the relative proportions of their respective parties overall. This peculiarity is accepted by the Zurich electorate because the resulting city council is proportional and all votes, regardless of district magnitude, now have equal weight. The system has since been adopted by other Swiss cities and cantons.[85][86]

Fair majority voting

Balinski has proposed another variant called fair majority voting (FMV) to replace single-winner plurality/majoritarian electoral systems, in particular the system used for the US House of Representatives. FMV introduces proportionality without changing the method of voting, the number of seats, or the – possibly gerrymandered – district boundaries. Seats would be apportioned to parties in a proportional manner at the state level.[86] In a related proposal for the UK parliament, whose elections are contested by many more parties, the authors note that parameters can be tuned to adopt any degree of proportionality deemed acceptable to the electorate. In order to elect smaller parties, a number of constituencies would be awarded to candidates placed fourth or even fifth in the constituency – unlikely to be acceptable to the electorate, the authors concede – but this effect could be substantially reduced by incorporating a third, regional, apportionment tier, or by specifying minimum thresholds.[87]

Other proportional systems

Reweighted range voting

Reweighted range voting (RRV) is a multi-winner voting system similar to STV in that voters can express support for multiple candidates, but different in that candidates are graded instead of ranked.[88][89][90] That is, a voter assigns a score to each candidate. The higher a candidate's scores, the greater the chance they will be among the winners.

Similar to STV, the vote counting procedure occurs in rounds. The first round of RRV is identical to range voting. All ballots are added with equal weight, and the candidate with the highest overall score is elected. In all subsequent rounds, ballots that support candidates who have already been elected are added with a reduced weight. Thus voters who support none of the winners in the early rounds are increasingly likely to elect one of their preferred candidates in a later round. The procedure has been shown to yield proportional outcomes if voters are loyal to distinct groups of candidates (e.g. political parties).[91]

RRV was used for the nominations in the Visual Effects category for recent Academy Award Oscars from 2013 through 2017.[92][93]

Proportional approval voting

Systems can be devised that aim at proportional representation but are based on approval votes on individual candidates (not parties). Such is the idea of Proportional approval voting (PAV).[94] When there are a lot of seats to be filled, as in a legislature, counting ballots under PAV may not be feasible, so sequential variants have been proposed, such as Sequential proportional approval voting (SPAV). This method is similar to reweighted range voting in that several winners are elected using a multi-round counting procedure in which ballots supporting already elected candidates are given reduced weights. Under SPAV, however, a voter can only choose to approve or disapprove of each candidate, as in approval voting. SPAV was used briefly in Sweden during the early 1900s.[95]

Asset voting

In asset voting,[88][96] the voters vote for candidates and then the candidates negotiate amongst each other and reallocate votes amongst themselves. Asset voting was proposed by Lewis Carroll in 1884[97] and has been more recently independently rediscovered and extended by Warren D. Smith and Forest Simmons.[98]

Evaluative Proportional Representation (EPR)

Similar to Majority Judgment voting that elects single winners, Evaluative Proportional Representation (EPR) elects all the members of a legislative body. Both systems remove the qualitative wasting of votes.[99] Each citizen grades the fitness for office of as many of the candidates as they wish as either Excellent (ideal), Very Good, Good, Acceptable, Poor, or Reject (entirely unsuitable). Multiple candidates may be given the same grade by a voter. Using EPR, each citizen elects their representative at-large for a city council. For a large and diverse state legislature, each citizen chooses to vote through any of the districts or official electoral associations in the country. Each voter grades any number of candidates in the whole country. Each elected representative has a different voting power (a different number of weighted votes) in the legislative body. This number is equal to the total number of votes given exclusively to each member from all citizens. Each member's weighted vote results from receiving one of the following from each voter: their highest grade, highest remaining grade, or proxy vote. No citizen's vote is "wasted"[100] Unlike all the other proportional representation systems, each EPR voter, and each self-identifying minority or majority is quantitatively represented with exact proportionality. Also, like Majority Judgment, EPR reduces by almost half both the incentives and possibilities for voters to use Tactical Voting.

.

History

One of the earliest proposals of proportionality in an assembly was by John Adams in his influential pamphlet Thoughts on Government, written in 1776 during the American Revolution:

It should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them. That it may be the interest of this Assembly to do strict justice at all times, it should be an equal representation, or in other words equal interest among the people should have equal interest in it.[101]

Mirabeau, speaking to the Assembly of Provence on January 30, 1789, was also an early proponent of a proportionally representative assembly:[102]

A representative body is to the nation what a chart is for the physical configuration of its soil: in all its parts, and as a whole, the representative body should at all times present a reduced picture of the people, their opinions, aspirations, and wishes, and that presentation should bear the relative proportion to the original precisely.

In February 1793, the Marquis de Condorcet led the drafting of the Girondist constitution which proposed a limited voting scheme with proportional aspects. Before that could be voted on, the Montagnards took over the National Convention and produced their own constitution. On June 24, Saint-Just proposed the single non-transferable vote, which can be proportional, for national elections but the constitution was passed on the same day specifying first-past-the-post voting.[102]

Already in 1787, James Wilson, like Adams a US Founding Father, understood the importance of multiple-member districts: "Bad elections proceed from the smallness of the districts which give an opportunity to bad men to intrigue themselves into office",[103] and again, in 1791, in his Lectures on Law: "It may, I believe, be assumed as a general maxim, of no small importance in democratical governments, that the more extensive the district of election is, the choice will be the more wise and enlightened".[104] The 1790 Constitution of Pennsylvania specified multiple-member districts for the state Senate and required their boundaries to follow county lines.[105]

STV or more precisely, an election method where voters have one transferable vote, was first invented in 1819 by an English schoolmaster, Thomas Wright Hill, who devised a "plan of election" for the committee of the Society for Literary and Scientific Improvement in Birmingham that used not only transfers of surplus votes from winners but also from losers, a refinement that later both Andræ and Hare initially omitted. But the procedure was unsuitable for a public election and wasn't publicised. In 1839, Hill's son, Rowland Hill, recommended the concept for public elections in Adelaide, and a simple process was used in which voters formed as many groups as there were representatives to be elected, each group electing one representative.[102]

The first practical PR election method, a list method, was conceived by Thomas Gilpin, a retired paper-mill owner, in a paper he read to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia in 1844: "On the representation of minorities of electors to act with the majority in elected assemblies". But the paper appears not to have excited any interest.[102]

A practical election using a single transferable vote was devised in Denmark by Carl Andræ, a mathematician, and first used there in 1855, making it the oldest PR system, but the system never really spread. It was re-invented (apparently independently) in the UK in 1857 by Thomas Hare, a London barrister, in his pamphlet The Machinery of Representation and expanded on in his 1859 Treatise on the Election of Representatives. The scheme was enthusiastically taken up by John Stuart Mill, ensuring international interest. The 1865 edition of the book included the transfer of preferences from dropped candidates and the STV method was essentially complete. Mill proposed it to the House of Commons in 1867, but the British parliament rejected it. The name evolved from "Mr.Hare's scheme" to "proportional representation", then "proportional representation with the single transferable vote", and finally, by the end of the 19th century, to "the single transferable vote".

In Australia, the political activist Catherine Helen Spence became an enthusiast of STV and an author on the subject. Through her influence and the efforts of the Tasmanian politician Andrew Inglis Clark, Tasmania became an early pioneer of the system, electing the world's first legislators through STV in 1896, prior to its federation into Australia.[106]

A party list proportional representation system was devised and described in 1878 by Victor D'Hondt in Belgium, which became the first country to adopt list PR in 1900 for its national parliament. D'Hondt's method of seat allocation, the D'Hondt method, is still widely used. Some Swiss cantons (beginning with Ticino in 1890) used the system before Belgium. Victor Considerant, a utopian socialist, devised a similar system in an 1892 book. Many European countries adopted similar systems during or after World War I. List PR was favoured on the Continent because the use of lists in elections, the scrutin de liste, was already widespread. STV was preferred in the English-speaking world because its tradition was the election of individuals.[35]

In the UK, the 1917 Speaker's Conference recommended STV for all multi-seat Westminster constituencies, but it was only applied to university constituencies, lasting from 1918 until 1950 when those constituencies were abolished. In Ireland, STV was used in 1918 in the University of Dublin constituency, and was introduced for devolved elections in 1921.

STV is currently used for two national lower houses of parliament, Ireland, since independence (as the Irish Free State) in 1922,[7] and Malta, since 1921, long before independence in 1966.[107] In Ireland, two attempts have been made by Fianna Fáil governments to abolish STV and replace it with the 'First Past the Post' plurality system. Both attempts were rejected by voters in referendums held in 1959 and again in 1968.. STV is also used for all other elections in Ireland including that of the presidency,

It is also used for the Northern Irish assembly and European and local authorities, Scottish local authorities, some New Zealand and Australian local authorities,[34] the Tasmanian (since 1907) and Australian Capital Territory assemblies, where the method is known as Hare-Clark,[64] and the city council in Cambridge, Massachusetts, (since 1941).[9][108]

PR is used by a majority of the world's 33 most robust democracies with populations of at least two million people; only six use plurality or a majoritarian system (runoff or instant runoff) for elections to the legislative assembly, four use parallel systems, and 23 use PR.[109] PR dominates Europe, including Germany and most of northern and eastern Europe; it is also used for European Parliament elections. France adopted PR at the end of World War II, but discarded it in 1958; it was used for parliament elections in 1986. Switzerland has the most widespread use of proportional representation, which is the system used to elect not only national legislatures and local councils, but also all local executives. PR is less common in the English-speaking world; New Zealand adopted MMP in 1993, but the UK, Canada, India and Australia all use plurality/majoritarian systems for legislative elections.

In Canada, STV was used by the cities of Edmonton and Calgary in Alberta from 1926 to 1955, and by Winnipeg in Manitoba from 1920 to 1953. In both provinces the alternative vote (AV) was used in rural areas. first-past-the-post was re-adopted in Alberta by the dominant party for reasons of political advantage, in Manitoba a principal reason was the underrepresentation of Winnipeg in the provincial legislature.[102]:223–234[110]

STV has some history in the United States. Between 1915 and 1962, twenty-four cities used the system for at least one election. In many cities, minority parties and other groups used STV to break up single-party monopolies on elective office. One of the most famous cases is New York City, where a coalition of Republicans and others imposed STV in 1936 as part of an attack on the Tammany Hall machine.[111] Another famous case is Cincinnati, Ohio, where, in 1924, Democrats and Progressive-wing Republicans imposed a council-manager charter with STV elections to dislodge the Republican machine of Rudolph K. Hynicka. Although Cincinnati's council-manager system survives, Republicans and other disaffected groups replaced STV with plurality-at-large voting in 1957.[112] From 1870 to 1980, Illinois used a semi-proportional cumulative voting system to elect its House of Representatives. Each district across the state elected both Republicans and Democrats year-after-year. Cambridge, Massachusetts (STV) and Peoria, Illinois (cumulative voting) continue to use PR. San Francisco had citywide elections in which people would cast votes for five or six candidates simultaneously, delivering some of the benefits of proportional representation.

Many political scientists argue that PR was adopted by parties on the right as a strategy to survive amid suffrage expansion, democratization and the rise of workers' parties. According to Stein Rokkan in a seminal 1970 study, parties on the right opted to adopt PR as a way to survive as competitive parties in situations when the parties on the right were not united enough to exist under majoritarian systems.[113] This argument was formalized and supported by Carles Boix in a 1999 study.[114] Amel Ahmed notes that prior to the adoption of PR, many electoral systems were based on majority or plurality rule, and that these systems risked eradicating parties on the right in areas were the working class was large in numbers. He therefore argues that parties on the right adopted PR as a way to ensure that they would survive as potent political forces amid suffrage expansion.[115] Other scholars have argued that the choice to adopt PR was also due to a demand by parties on the left to ensure a foothold in politics, as well as to encourage a consensual system that would help the left realize its preferred economic policies.[116]

List of countries using proportional representation

The table below lists the countries that use a PR electoral system to fill a nationwide elected body. Detailed information on electoral systems applying to the first chamber of the legislature is maintained by the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network.[117][118] (See also the complete list of electoral systems by country.)

| Country | Type | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albania | Party list, 4% national threshold or 2.5% in a district |

| 2 | Algeria | Party list |

| 3 | Angola | Party list |

| 4 | Argentina | Party list in the Chamber of Deputies |

| 5 | Armenia | Two-tier party list

[119] Nationwide closed lists and open lists in each of 13 election districts. If needed to ensure a stable majority with at least 54% of the seats, the two best-placed parties participate in a run-off vote to receive a majority bonus. Threshold of 5% for parties and 7% for election blocs. |

| 6 | Aruba | Party list |

| 7 | Australia | For Senate only, single transferable vote |

| 8 | Austria | Party list, 4% threshold |

| 9 | Belgium | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 10 | Bénin | Party list |

| 11 | Bolivia | Mixed-member proportional representation, 3% threshold |

| 12 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Party list |

| 13 | Brazil | Party list |

| 14 | Bulgaria | Party list, 4% threshold |

| 15 | Burkina Faso | Party list |

| 16 | Burundi | Party list, 2% threshold |

| 17 | Cambodia | Party list |

| 18 | Cape Verde | Party list |

| 19 | Chile | Party list |

| 21 | China (People's Republic of) | Party list, with approval voting |

| 20 | Colombia | Party list |

| 21 | Costa Rica | Party list |

| 22 | Croatia | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 23 | Cyprus | Party list |

| 24 | Czech Republic | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 25 | Denmark | Two-tier party list, 2% threshold |

| 26 | Dominican Republic | Party list |

| 27 | East Timor | Party list |

| 28 | El Salvador | Party list |

| 29 | Equatorial Guinea | Party list |

| 30 | Estonia | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 31 | European Union | Each member state chooses its own PR system |

| 32 | Faroe Islands | Party list |

| 33 | Fiji | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 34 | Finland | Party list |

| 35 | Germany | Mixed-member proportional representation, 5% (or 3 district winners) threshold |

| 36 | Greece | Two-tier party list

Nationwide closed lists and open lists in multi-member districts. The winning party used to receive a majority bonus of 50 seats (out of 300), but this system will be abolished two elections after 2016.[120] In 2020 parliament voted to return to the majority bonus two elections thereafter.[121] Threshold of 3%. |

| 37 | Greenland | Party list |

| 38 | Guatemala | Party list |

| 39 | Guinea-Bissau | Party list |

| 40 | Guyana | Party list |

| 41 | Honduras | Party list |

| 41 | Hong Kong | Party list |

| 42 | Iceland | Party list |

| 43 | Indonesia | Party list, 4% threshold |

| 44 | Iraq | Party list |

| 45 | Ireland | Single transferable vote |

| 46 | Israel | Party list, 3.25% threshold |

| 46 | Italy | Mixed, 3% threshold |

| 47 | Kazakhstan | Party list, 7% threshold |

| 48 | Kosovo | Party list |

| 49 | Kyrgyzstan | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 50 | Latvia | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 51 | Lebanon | Party list |

| 52 | Lesotho | Mixed-member proportional representation |

| 53 | Liechtenstein | Party list, 8% threshold |

| 54 | Luxembourg | Party list |

| 55 | Macedonia | Party list |

| 56 | Malta | Single transferable vote |

| 57 | Moldova | Party list, 6% threshold |

| 58 | Montenegro | Party list |

| 59 | Mozambique | Party list |

| 60 | Namibia | Party list |

| 61 | Netherlands | Party list |

| 62 | New Zealand | Mixed-member proportional representation, 5% (or 1 district winner) threshold |

| 63 | Nicaragua | Party list |

| 64 | Northern Ireland | Single transferable vote |

| 65 | Norway | Two-tier party list, 4% national threshold |

| 66 | Paraguay | Party list |

| 67 | Peru | Party list |

| 68 | Poland | Party list, 5% threshold or more |

| 69 | Portugal | Party list |

| 70 | Romania | Party list |

| 71 | Rwanda | Party list |

| 72 | San Marino | Party list

If needed to ensure a stable majority, the two best-placed parties participate in a run-off vote to receive a majority bonus. Threshold of 3.5%. |

| 73 | São Tomé and Príncipe | Party list |

| 74 | Serbia | Party list, 5% threshold or less |

| 75 | Sint Maarten | Party list |

| 76 | Slovakia | Party list, 5% threshold |

| 77 | Slovenia | Party list, 4% threshold |

| 78 | South Africa | Party list |

| 79 | Spain | Party list, 3% threshold in small constituencies |

| 80 | Sri Lanka | Party list |

| 81 | Suriname | Party list |

| 82 | Sweden | Two-tier party list, 4% national threshold or 12% in a district |

| 83 | Switzerland | Party list |

| 84 | Togo | Party list |

| 85 | Tunisia | Party list |

| 86 | Turkey | Party list, 10% threshold |

| 87 | Uruguay | Party list |

See also

- Hare quota

- Sainte-Laguë method

- Interactive representation

- Direct representation

- One man, one vote

References

- Mill, John Stuart (1861). "Chapter VII, Of True and False Democracy; Representation of All, and Representation of the Majority only". Considerations on Representative Government. London: Parker, Son, & Bourn.

- "Proportional Representation (PR)". ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Electoral System Design: the New International IDEA Handbook". International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. 2005. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Amy, Douglas J. "How Proportional Representation Elections Work". FairVote. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Additional Member System". London: Electoral Reform Society. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ACE Project: The Electoral Knowledge Network. "Electoral Systems Comparative Data, Table by Question". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Gallagher, Michael. "Ireland: The Archetypal Single Transferable Vote System" (PDF). Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Hirczy de Miño, Wolfgang, University of Houston; Lane, John, State University of New York at Buffalo (1999). "Malta: STV in a two-party system" (PDF). Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Amy, Douglas J. "A Brief History of Proportional Representation in the United States". FairVote. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ACE Project Electoral Knowledge Network. "The Systems and Their Consequences". Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Canadian House of Commons Special Committee on Electoral Reform (December 2016). "Strengthening Democracy in Canada: Principles, Process and Public Engagement for Electoral Reform".

- Forder, James (2011). The case against voting reform. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-825-8.

- Amy, Douglas. "Proportional Representation Voting Systems". Fairvote.org. Takoma Park. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Norris, Pippa (1997). "Choosing Electoral Systems: Proportional, Majoritarian and Mixed Systems" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Colin Rallings; Michael Thrasher. "The 2005 general election: analysis of the results" (PDF). Electoral Commission, Research, Electoral data. London: Electoral Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Commission On Electoral Reform, Hansard Society for Parliamentary Government (1976). "Report of the Hansard Society Commission on Electoral Reform". Hansard Society. London.

- "1993 Canadian Federal Election Results". University of British Columbia. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "Election 2015 - BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- Ana Nicolaci da Costa; Charlotte Greenfield (September 23, 2017). "New Zealand's ruling party ahead after poll but kingmaker in no rush to decide". Reuters.

- Roberts, Iain (29 June 2010). "People in broad church parties should think twice before attacking coalitions". Liberal Democrat Voice. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "A look at the evidence". Fair Vote Canada. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Amy, Douglas J. "Single Transferable Vote Or Choice Voting". FairVote. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Electoral Reform Society's evidence to the Joint Committee on the Draft Bill for House of Lords Reform". Electoral Reform Society. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Harris, Paul (20 November 2011). "'America is better than this': paralysis at the top leaves voters desperate for change". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Krugman, Paul (19 May 2012). "Going To Extreme". The Conscience of a Liberal, Paul Krugman Blog. The New York Times Co. Retrieved 24 Nov 2014.

- Mollison, Denis. "Fair votes in practice STV for Westminster" (PDF). Heriot Watt University. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Democrats' Edge in House Popular Vote Would Have Increased if All Seats Had Been Contested". FairVote. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- Cox, Gary W.; Fiva, Jon H.; Smith, Daniel M. (2016). "The Contraction Effect: How Proportional Representation Affects Mobilization and Turnout" (PDF). The Journal of Politics. 78 (4): 1249–1263. doi:10.1086/686804. hdl:11250/2429132.

- Amy, Douglas J (2002). Real Choices / New Voices, How Proportional Representation Elections Could Revitalize American Democracy. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231125499.

- Mollison, Denis (2010). "Fair votes in practice: STV for Westminster". Heriot-Watt University. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane (April 13, 2014). "Legal But Not Fair (Hungary)". The Conscience of a Liberal, Paul Krugman Blog. The New York Times Co. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (11 July 2014). "Hungary, Parliamentary Elections, 6 April 2014: Final Report". OSCE.

- "Voting Counts: Electoral Reform for Canada" (PDF). Law Commission of Canada. 2004. p. 22.

- "Single Transferable Vote". London: Electoral Reform Society. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Humphreys, John H (1911). Proportional Representation, A Study in Methods of Election. London: Methuen & Co.Ltd.

- (Dutch) "Evenredige vertegenwoordiging" Check

|url=value (help). www.parlement.com (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-01-28. - Carey, John M.; Hix, Simon (2011). "The Electoral Sweet Spot: Low-Magnitude Proportional Electoral Systems" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 55 (2): 383–397. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00495.x.

- "Electoral reform in Chile: Tie breaker". The Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Laver, Michael (1998). "A new electoral system for Ireland?" (PDF). The Policy Institute, Trinity College, Dublin.

- "Joint Committee on the Constitution" (PDF). Dublin: Houses of the Oireachtas. July 2010.

- "National projections" (PDF). Monopoly Politics 2014 and the Fair Voting Solution. FairVote. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Lubell, Maayan (March 11, 2014). "Israel ups threshold for Knesset seats despite opposition boycott". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- "Party Magnitude and Candidate Selection". ACE Electoral Knowledge Network.

- O'Kelly, Michael. "The fall of Fianna Fáil in the 2011 Irish general election". Significance. Royal Statistical Society, American Statistical Association. Archived from the original on 2014-08-06.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "America Has an Electoral Problem: Here's How We Can Fix It". Crossfire KM. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Karpov, Alexander (2008). "Measurement of disproportionality in proportional representation systems". Mathematical and Computer Modelling. 48 (9–10): 1421–1438. doi:10.1016/j.mcm.2008.05.027.

- Wada, Junichiro (2016). "Apportionment behind the veil of uncertainty". The Japanese Economic Review. 67 (3): 348–360. doi:10.1111/jere.12093.

- Dunleavy, Patrick; Margetts, Helen (2004). "How proportional are the 'British AMS' systems?". Representation. 40 (4): 317–329. doi:10.1080/00344890408523280. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Kestelman, Philip (March 1999). "Quantifying Representativity". Voting Matters (10). Retrieved 10 August 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, I D (May 1997). "Measuring proportionality". Voting Matters (8).

- As counted from the table in http://www.wahlrecht.de/ausland/europa.htm [in German]; "Vorzugsstimme(n)" means "open list".

- "Party List PR". Electoral Reform Society. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Gordon Gibson (2003). Fixing Canadian Democracy. The Fraser Institute. p. 76. ISBN 9780889752016.

- Gallagher, Michael; Mitchell, Paul (2005). The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-925756-0.

- "The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark". Copenhagen: Ministry of the Interior and Health. 2011. Retrieved 1 Sep 2014.

- "The main features of the Norwegian electoral system". Oslo: Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation. 2017-07-06. Retrieved 1 Sep 2014.

- "The Swedish electoral system". Stockholm: Election Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 1 Sep 2014.

- "Fair Voting/Proportional Representation". FairVote. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Tideman, Nicolaus (1995). "The Single Transferable Vote". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 9 (1): 27–38. doi:10.1257/jep.9.1.27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O’Neill, Jeffrey C. (July 2006). "Comments on the STV Rules Proposed by British Columbia". Voting Matters (22). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- David M. Farrell; Ian McAllister (2006). The Australian Electoral System: Origins, Variations, and Consequences. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0868408583.

- "Referendum 2011: A look at the STV system". The New Zealand Herald. Auckland: The New Zealand Herald. 1 Nov 2011. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- "Change the Way We Elect? Round Two of the Debate". The Tyee. Vancouver. 30 Apr 2009. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- "The Hare-Clark System of Proportional Representation". Melbourne: Proportional Representation Society of Australia. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- "Above the line voting". Perth: University of Western Australia. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- "Glossary of Election Terms". Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- Hill, I.D. (November 2000). "How to ruin STV". Voting Matters (12). Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Green, Anthony (20 April 2005). "Above or below the line? Managing preference votes". Australia: On Line Opinion. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- Terry, Chris (5 April 2012). "Serving up a dog's breakfast". London: Electoral Reform Society. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 21 Nov 2014.

- ACE Project Electoral Knowledge Network. "Mixed Systems". Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Massicotte, Louis (2004). In Search of Compensatory Mixed Electoral System for Québec (PDF) (Report).

- Bochsler, Daniel (May 13, 2010). "Chapter 5, How Party Systems Develop in Mixed Electoral Systems". Territory and Electoral Rules in Post-Communist Democracies. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230281424.

- "Electoral Systems and the Delimitation of Constituencies". International Foundation for Electoral Systems. 2 Jul 2009.

- Moser, Robert G. (December 2004). "Mixed electoral systems and electoral system effects: controlled comparison and cross-national analysis". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 575–599. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(03)00056-8.

- Massicotte, Louis (September 1999). "Mixed electoral systems: a conceptual and empirical survey". Electoral Studies. 18 (3): 341–366. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(98)00063-8.

- "MMP Voting System". Wellington: Electoral Commission New Zealand. 2011. Retrieved 10 Aug 2014.

- "Deutschland hat ein neues Wahlrecht" (in German). Zeit Online. 22 February 2013.

- "Report of the Electoral Commission on the Review of the MMP Voting System". Wellington: Electoral Commission New Zealand. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 10 Aug 2014.

- Sean Graham (April 4, 2016). "Dual-Member Mixed Proportional: A New Electoral System for Canada" (PDF).

- Antony Hodgson (Jan 21, 2016). "Why a referendum on electoral reform would be undemocratic". The Tyee.

- PEI Special Committee on Democratic Renewal (April 15, 2016). "Recommendations in Response to the White Paper on Democratic Renewal - A Plebiscite Question" (PDF).

- Kerry Campbell (April 15, 2016). "P.E.I. electoral reform committee proposes ranked ballot". CBC News.

- Elections PEI (November 7, 2016). "Plebiscite Results". Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- Susan Bradley (November 7, 2016). "P.E.I. plebiscite favours mixed member proportional representation". CBC News.

- Pukelsheim, Friedrich (September 2009). "Zurich's New Apportionment" (PDF). German Research. 31 (2): 10–12. doi:10.1002/germ.200990024. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Balinski, Michel (February 2008). "Fair Majority Voting (or How to Eliminate Gerrymandering)". The American Mathematical Monthly. 115 (2): 97–113. doi:10.1080/00029890.2008.11920503. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Akartunali, Kerem; Knight, Philip A. (January 2014). "Network Models and Biproportional Apportionment for Fair Seat Allocations in the UK Elections" (PDF). University of Strathclyde. Retrieved 10 August 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Smith, Warren (18 June 2006). "Comparative survey of multiwinner election methods" (PDF).

- Kok, Jan; Smith, Warren. "Reweighted Range Voting – a Proportional Representation voting method that feels like range voting". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Ryan, Ivan. "Reweighted Range Voting – a Proportional Representation voting method that feels like range voting". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Smith, Warren (6 August 2005). "Reweighted range voting – new multiwinner voting method" (PDF).

- "89th Annual Academy Awards of Merit for Achievements during 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Rule Twenty-Two: Special Rules for the Visual Effects Award". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Brill, Markus; Laslier, Jean-François; Skowron, Piotr (2016). "Multiwinner Approval Rules as Apportionment Methods". arXiv:1611.08691 [cs.GT].

- Aziz, Haris; Serge Gaspers, Joachim Gudmundsson, Simon Mackenzie, Nicholas Mattei, Toby Walsh (2014). "Computational Aspects of Multi-Winner Approval Voting". Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems. pp. 107–115. arXiv:1407.3247v1. ISBN 978-1-4503-3413-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smith, Warren (8 March 2005). ""Asset voting" scheme for multiwinner elections" (PDF).

- Dodgson, Charles (1884). "The Principles of Parliamentary Representation". London: Harrison and Sons. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

The Elector must understand that, in giving his vote to A, he gives it to him as his absolute property, to use for himself, or to transfer to other Candidates, or to leave unused.

- Smith, Warren. "Asset voting – an interesting and very simple multiwinner voting system". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- M. Balinski & R. Laraki (2010). Majority Judgment. MIT. ISBN 978-0-262-01513-4.

- Bosworth, Stephen; Corr, Ander & Leonard, Stevan (July 8, 2019). "Legislatures Elected by Evaluative Proportional Representation (EPR): an Algorithm". Journal of Political Risk. 7 (8). Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Adams, John (1776). "Thoughts on Government". The Adams Papers Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Hoag, Clarence; Hallett, George (1926). Proportional Representation. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Madison, James. "Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, Wednesday, June 6". TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- Wilson, James (1804). "Vol 2, Part II, Ch.1 Of the constitutions of the United States and of Pennsylvania – Of the legislative department, I, of the election of its members". The Works of the Honourable James Wilson. Constitution Society. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- "Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania – 1790, art.I,§ VII, Of districts for electing Senators". Duquesne University. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- Newman, Hare-Clark in Tasmania, p. 7-10

- Hirczy de Miño, Wolfgang (1997). "Malta: Single-Transferable Vote with Some Twists". ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. Retrieved 5 Dec 2014.

- "Adoption of Plan E". Welcome to the City of Cambridge. City of Cambridge, MA. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- "Proportional Representation in Most Robust Democracies". Fair Vote: The Center for Voting And Democracy. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Jansen, Harold John (1998). "The Single Transferable Vote in Alberta and Manitoba" (PDF). Library and Archives Canada. University of Alberta. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- Santucci, Jack (2016-11-10). "Party Splits, Not Progressives". American Politics Research. 45 (3): 494–526. doi:10.1177/1532673x16674774. ISSN 1532-673X.

- Barber, Kathleen (1995). Proportional Representation and Election Reform in Ohio. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0814206607.

- Rokkan, Stein (1970). Citizens, elections, parties: approaches to the comparative study of the processes of development. McKay.

- Boix, Carles (1999). "Setting the Rules of the Game: The Choice of Electoral Systems in Advanced Democracies". The American Political Science Review. 93 (3): 609–624. doi:10.2307/2585577. hdl:10230/307. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 2585577.

- Ahmed, Amel (2012). Democracy and the Politics of Electoral System Choice: Engineering Electoral Dominance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139382137. ISBN 9781139382137.