The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Italian: Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, lit. '"The good, the ugly, the bad"') is a 1966 Italian epic Spaghetti Western film directed by Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood as "the Good", Lee Van Cleef as "the Bad", and Eli Wallach as "the Ugly".[10] Its screenplay was written by Age & Scarpelli, Luciano Vincenzoni and Leone (with additional screenplay material and dialogue provided by an uncredited Sergio Donati),[11] based on a story by Vincenzoni and Leone. Director of photography Tonino Delli Colli was responsible for the film's sweeping widescreen cinematography, and Ennio Morricone composed the film's score including its main theme. It is an Italian-led production with co-producers in Spain, West Germany and the United States.

| The Good, the Bad and the Ugly | |

|---|---|

Italian theatrical release poster by Renato Casaro[1] | |

| Directed by | Sergio Leone |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Edited by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 177 minutes |

| Country | Italy[2][3][5][6] |

| Language | |

| Budget | $1.2 million[8] |

| Box office | $25.1 million (North America)[9] |

The film is known for Leone's use of long shots and close-up cinematography, as well as his distinctive use of violence, tension, and stylistic gunfights. The plot revolves around three gunslingers competing to find fortune in a buried cache of Confederate gold amid the violent chaos of the American Civil War (specifically the New Mexico Campaign in 1862), while participating in many battles and duels along the way.[12] The film was the third collaboration between Leone and Clint Eastwood, and the second with Lee Van Cleef.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was marketed as the third and final instalment in the Dollars Trilogy, following A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More. The film was a financial success, grossing over $25 million at the box office, and is credited with having catapulted Eastwood into stardom.[13] Due to general disapproval of the Spaghetti Western genre at the time, critical reception of the film following its release was mixed, but it gained critical acclaim in later years.

Plot

In 1862, during the American Civil War, a trio of bounty hunters attempt to kill fugitive Mexican bandit Tuco Ramírez. Tuco shoots the three bounty hunters and escapes on horseback. Elsewhere, a mercenary known as "Angel Eyes" interrogates former Confederate soldier Stevens, whom Angel Eyes is contracted to kill, about Jackson, a fugitive who stole a cache of Confederate gold. Angel Eyes makes Stevens tell him the new name Jackson is using: Bill Carson. Stevens offers Angel Eyes $1,000 to kill Baker, Angel Eyes's employer. Angel Eyes accepts the new commission, but also kills Stevens as he leaves, fulfilling his contract with Baker. He then returns to Baker, collects his fee for killing Stevens, and then shoots Baker, fulfilling his commission from Stevens. Meanwhile, Tuco is rescued from three bounty hunters by a nameless drifter to whom Tuco refers as "Blondie", who delivers him to the local sheriff to collect his $2,000 bounty. As Tuco is about to be hanged, Blondie severs Tuco's noose by shooting it, and sets him free. The two escape on horseback and split the bounty in a lucrative money-making scheme. They repeat the process in another town for more reward money. Blondie grows weary of Tuco's complaints, and abandons him without horse or water in the desert. Tuco manages to walk to a village, and then tracks Blondie to a town occupied by Confederate troops. Tuco holds Blondie at gunpoint, planning to force him to hang himself, but Union forces shell the town, allowing Blondie to escape.

Following an arduous search, Tuco recaptures Blondie and force-marches him across a desert until Blondie collapses from dehydration. As Tuco prepares to shoot him, he sees a runaway carriage. Inside are several dead Confederate soldiers and a near-death Bill Carson, who promises Tuco $200,000 in Confederate gold, buried in a grave in Sad Hill Cemetery. Tuco demands to know the name on the grave, but Carson collapses from thirst before answering. When Tuco returns with water, Carson has died and Blondie, slumped next to him, reveals that Carson recovered and told him the name on the grave before dying. Tuco, who now has strong motivation to keep Blondie alive, gives him water and takes him to a nearby frontier mission, where his brother is the Abbot, to recover.

After Blondie's recovery, the two leave in Confederate uniforms from Carson's carriage, only to be captured by Union soldiers and remanded to the prisoner-of-war camp of Batterville. At roll call, Tuco answers for "Bill Carson", getting the attention of Angel Eyes, now a disguised Union sergeant at the camp. Angel Eyes tortures Tuco, who reveals the name of the cemetery, but confesses that only Blondie knows the name on the grave. Realizing that Blondie will not yield to torture, Angel Eyes offers him an equal share of the gold and a partnership. Blondie agrees and rides out with Angel Eyes and his gang. Tuco is packed on a train to be executed, but escapes.

Blondie, Angel Eyes, and his henchmen arrive in an evacuated town. Tuco, having fled to the same town, takes a bath in a ramshackle hotel and is surprised by Elam, one of the three bounty hunters who tried to kill him. Tuco shoots Elam, causing Blondie to investigate the gunshots. He finds Tuco, and they agree to resume their old partnership. The pair kill Angel Eyes's men, but discover that Angel Eyes himself has escaped.

Tuco and Blondie travel toward Sad Hill, but their way is blocked by Union troops on one side of a strategic bridge, with Confederates on the other. Blondie decides to destroy the bridge to disperse the two armies to allow access to the cemetery. As they wire the bridge with explosives, Tuco suggests they share information, in case one person dies before he can help the other. Tuco reveals the name of the cemetery, while Blondie says "Arch Stanton" is the name on the grave. After the bridge is demolished, the armies disperse, and Tuco steals a horse and rides to Sad Hill to claim the gold for himself. He finds Arch Stanton's grave and begins digging. Blondie arrives and encourages him at gunpoint to continue. A moment later, Angel Eyes surprises them both. Blondie opens Stanton's grave, revealing only a skeleton, no gold. Blondie states that he lied about the name on the grave, and offers to write the real name of the grave on a rock. Placing it face-down in the courtyard of the cemetery, he challenges Tuco and Angel Eyes to a three-way duel.

The trio stare each other down. Everyone draws, and Blondie shoots and kills Angel Eyes, while Tuco discovers that his own gun was unloaded by Blondie the night before. Blondie reveals that the gold is actually in the grave beside Arch Stanton's, marked "Unknown". Tuco is initially elated to find bags of gold, but Blondie holds him at gunpoint and orders him into a hangman's noose beneath a tree. Blondie binds Tuco's hands and forces him to stand balanced precariously atop an unsteady grave marker while he takes half the gold and rides away. As Tuco screams for mercy, Blondie returns into sight. Blondie severs the rope with a rifle shot, dropping Tuco, alive but tied up, onto his share of the gold. Tuco curses loudly while Blondie rides off into the horizon.

Cast

The trio

- Clint Eastwood as "Blondie" (a.k.a. the Man with No Name): The Good, a taciturn, confident bounty hunter who teams up with Tuco, and Angel Eyes temporarily, to find the buried gold. Blondie and Tuco have an ambivalent partnership. Tuco knows the name of the cemetery where the gold is hidden, but Blondie knows the name of the grave where it is buried, forcing them to work together to find the treasure. In spite of this greedy quest, Blondie's pity for the dying soldiers in the chaotic carnage of the War is evident. "I've never seen so many men wasted so badly," he remarks. He also comforts a dying soldier by laying his coat over him and letting him smoke his cigar. Rawhide had ended its run as a series in 1966, and at that point neither A Fistful of Dollars nor For a Few Dollars More had been released in the United States. When Leone offered Clint Eastwood a role in his next movie, it was the only big film offer he had; however, Eastwood still needed to be convinced to do it. Leone and his wife travelled to California to persuade him. Two days later, he agreed to make the film upon being paid $250,000[14] and getting 10% of the profits from the North American markets—a deal with which Leone was not happy.[15] In the original Italian script for the film, he is named "Joe" (his nickname in A Fistful of Dollars), but is referred to as Blondie in the Italian and English dialogue.[11]

- Lee Van Cleef as Angel Eyes: The Bad, a ruthless, confident, borderline-sadistic mercenary who takes a pleasure in killing and always finishes a job he is paid for; usually tracking and assassination. When Blondie and Tuco are captured while posing as Confederate soldiers, Angel Eyes is the Union sergeant who interrogates and has Tuco tortured, eventually learning the name of the cemetery where the gold is buried, but not the name on the tombstone. Angel Eyes forms a fleeting partnership with Blondie, but Tuco and Blondie turn on Angel Eyes when they get their chance. Originally, Leone wanted Enrico Maria Salerno (who had dubbed Eastwood's voice for the Italian versions of the Dollars Trilogy films)[16] or Charles Bronson to play Angel Eyes, but the latter was already committed to playing in The Dirty Dozen (1967). Leone thought about working with Lee Van Cleef again: "I said to myself that Van Cleef had first played a romantic character in For a Few Dollars More. The idea of getting him to play a character who was the opposite of that began to appeal to me."[17] In the original working script, Angel Eyes was named "Banjo", but is referred to as "Sentenza" (meaning "Sentence" or "Judgement") in the Italian version. Eastwood came up with the name Angel Eyes on the set, for his gaunt appearance and expert marksmanship.[11]

- Eli Wallach as Tuco Benedicto Pacífico Juan María Ramírez (known as "The Rat" according to Blondie): The Ugly, a fast-talking, comically oafish yet also cunning, cagey, resilient and resourceful Mexican bandit who is wanted by the authorities for a long list of crimes. Tuco manages to discover the name of the cemetery where the gold is buried, but he does not know the name of the grave. This state of affairs forces Tuco to become reluctant partners with Blondie. The director originally considered Gian Maria Volonté (who portrayed the villains in both the preceding films) for the role of Tuco, but felt that the role required someone with "natural comic talent". In the end, Leone chose Eli Wallach, based on his role in How the West Was Won (1962), in particular, his performance in "The Railroads" scene.[17] In Los Angeles, Leone met Wallach, who was skeptical about playing this type of character again, but after Leone screened the opening credit sequence from For a Few Dollars More, Wallach said: "When do you want me?"[17] The two men got along famously, sharing the same bizarre sense of humor. Leone allowed Wallach to make changes to his character in terms of his outfit and recurring gestures. Both Eastwood and Van Cleef realized that the character of Tuco was close to Leone's heart, and the director and Wallach became good friends. They communicated in French, which Wallach spoke badly and Leone spoke well. Van Cleef observed, "Tuco is the only one of the trio the audience gets to know all about. We meet his brother and find out where he came from and why he became a bandit. But Clint's and Lee's characters remain mysteries."[17] In the theatrical trailer, Angel Eyes is referred to as The Ugly and Tuco, The Bad.[18] This is due to a translation error; the original Italian title translates to "The Good [one], the Ugly [one], the Bad [one]".

Supporting cast

- Aldo Giuffrè as Alcoholic Union Captain Clinton

- Mario Brega as Corporal Wallace

- Luigi Pistilli as Father Pablo Ramírez

- Al Mulock as Elam, one-Armed Bounty Hunter

- Antonio Casas as Stevens

- Antonio Casale as Jackson/Bill Carson

- Antonio Molino Rojo as Captain Harper

- Rada Rassimov as Maria

- Enzo Petito as Storekeeper

- Chelo Alonso as Stevens' Wife

- Claudio Scarchilli as Mexican Peon

- John Bartha as Sheriff

- Livio Lorenzon as Baker

- Sandro Scarchilli as Mexican Peon

- Benito Stefanelli as Member of Angel Eyes' Gang

- Angelo Novi as Monk

- Aldo Sambrell as Member of Angel Eyes' Gang

- Sergio Mendizábal as Blonde Bounty Hunter

- Lorenzo Robledo as Clem

- Richard Alagich as Soldato Unione all'Arresto

- Fortunato Arena as 1st Sombrero Onlooker at Tuco's 1st Hanging

- Román Ariznavarreta as Bounty Hunter

- Silvana Bacci as Messicana con Biondo

- Joseph Bradley as Old Soldier

- Frank Braña as Bounty Hunter #2

- Amerigo Castrighella as 2nd Sombrero Onlooker at Tuco's 1st Hanging

- Saturno Cerra as Bounty Hunter

- Luigi Ciavarro as Member of Angel Eyes' Gang

- William Conroy as Confederate Soldier

- Antonio Contreras as Violinista al Campo

- Axel Darna as Soldato Confederato Morente

- Tony Di Mitri as Deputy

- Alberigo Donadeo as Spettatore Prima Impiccagione

- Attilio Dottesio as 3rd Sombrero Onlooker at Tuco's 1st Hanging

- Luis Fernández de Eribe as Soldier Coat

- Veriano Ginesi as Bald Onlooker at Tuco's 1st Hanging

- Joyce Gordon as Maria (voice)

- Bernie Grant as Clinton – Alcoholic Union Captain (voice)

- Jesús Guzmán as Pardue the Hotel Owner

- Víctor Israel as Sergeant at Confederate Fort

- Nazzareno Natale as Mexican Bounty Hunter

- Ricardo Palacios as Barista a Socorro

- Antonio Palombi as Vecchio Sergente

- Julio Martínez Piernavieja as Corista al Campo[19]

- Jesús Porras as Suonatore Armonica al Campo

- Romano Puppo as Member of Angel Eyes' Gang

- Antoñito Ruiz as Stevens' Youngest Son

- Aysanoa Runachagua as Pistolero Recruited by Tuco in the Cave

- Enrique Santiago as Mexican Bounty Hunter

- José Terrón as Thomas 'Shorty' Larson

- Franco Tocci as Soldato Unione con Sigaro

Development

Pre-production

After the success of For a Few Dollars More, executives at United Artists approached the film's screenwriter, Luciano Vincenzoni, to sign a contract for the rights to the film and for the next one. He, producer Alberto Grimaldi and Sergio Leone had no plans, but with their blessing, Vincenzoni pitched an idea about "a film about three rogues who are looking for some treasure at the time of the American Civil War".[17] The studio agreed, but wanted to know the cost for this next film. At the same time, Grimaldi was trying to broker his own deal, but Vincenzoni's idea was more lucrative. The two men struck an agreement with UA for a million-dollar budget, with the studio advancing $500,000 up front and 50% of the box office takings outside of Italy. The total budget was eventually $1.2 million.[11]

Leone built upon the screenwriter's original concept to "show the absurdity of war ... the Civil War which the characters encounter. In my frame of reference, it is useless, stupid: it does not involve a 'good cause.'"[17] An avid history buff, Leone said, "I had read somewhere that 120,000 people died in Southern camps such as Andersonville. I was not ignorant of the fact that there were camps in the North. You always get to hear about the shameful behavior of the losers, never the winners."[17] The Batterville Camp where Blondie and Tuco are imprisoned was based on steel engravings of Andersonville. Many shots in the film were influenced by archival photographs taken by Mathew Brady. As the film took place during the Civil War, it served as a prequel for the other two films in the trilogy, which took place after the war.[20]

While Leone developed Vincenzoni's idea into a script, the screenwriter recommended the comedy-writing team of Agenore Incrucci and Furio Scarpelli to work on it with Leone and Sergio Donati. According to Leone, "I couldn't use a single thing they'd written. It was the grossest deception of my life."[17] Donati agreed, saying, "There was next to nothing of them in the final script. They only wrote the first part. Just one line."[17] Vincenzoni claims that he wrote the screenplay in 11 days, but he soon left the project after his relationship with Leone soured. The three main characters all contain autobiographical elements of Leone. In an interview he said, "[Sentenza] has no spirit, he's a professional in the most banal sense of the term. Like a robot. This isn't the case with the other two. On the methodical and careful side of my character, I'd be nearer il Biondo (Blondie): but my most profound sympathy always goes towards the Tuco side ... He can be touching with all that tenderness and all that wounded humanity."[17] Film director Alex Cox suggests that the cemetery-buried gold hunted by the protagonists may have been inspired by rumours surrounding the anti-Communist Gladio terrorists, who hid many of their 138 weapons caches in cemeteries.[16]

Eastwood received a percentage-based salary, unlike the first two films where he received a straight fee salary. When Lee Van Cleef was again cast for another Dollars film, he joked "the only reason they brought me back was because they forgot to kill me off in For A Few Dollars More".[20]

The film's working title was I due magnifici straccioni (The Two Magnificent Tramps). It was changed just before shooting began when Vincenzoni thought up Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Ugly, the Bad), which Leone loved. In the United States, United Artists considered using the original Italian translation, River of Dollars, or The Man With No Name, but decided on The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.[18]

Production

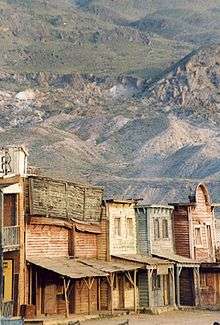

Filming began at the Cinecittà studio in Rome again in mid-May 1966, including the opening scene between Eastwood and Wallach when Blondie captures Tuco for the first time and sends him to jail.[21] The production then moved on to Spain's plateau region near Burgos in the north, which doubled for the southwestern United States, and again shot the western scenes in Almería in the south of Spain.[22] This time, the production required more elaborate sets, including a town under cannon fire, an extensive prison camp and an American Civil War battlefield; and for the climax, several hundred Spanish soldiers were employed to build a cemetery with several thousand gravestones to resemble an ancient Roman circus.[22] For the scene where the bridge was blown up, it had to be filmed twice, as in the first take all three cameras were destroyed by the explosion.[23] Eastwood remembers, "They would care if you were doing a story about Spaniards and about Spain. Then they'd scrutinize you very tough, but the fact that you're doing a western that's supposed to be laid in southwest America or Mexico, they couldn't care less what your story or subject is."[17] Top Italian cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli was brought in to shoot the film and was prompted by Leone to pay more attention to light than in the previous two films; Ennio Morricone composed the score once again. Leone was instrumental in asking Morricone to compose a track for the final Mexican stand-off scene in the cemetery, asking him to compose what felt like "the corpses were laughing from inside their tombs", and asked Delli Colli to create a hypnotic whirling effect interspersed with dramatic extreme close ups, to give the audience the impression of a visual ballet.[22] Filming concluded in July 1966.[14]

Eastwood was not initially pleased with the script and was concerned he might be upstaged by Wallach. "In the first film I was alone," he told Leone. "In the second, we were two. Here we are three. If it goes on this way, in the next one I will be starring with the American cavalry."[24] As Eastwood played hard-to-get in accepting the role (inflating his earnings up to $250,000, another Ferrari[25] and 10% of the profits in the United States when eventually released there), he was again encountering publicist disputes between Ruth Marsh, who urged him to accept the third film of the trilogy, and the William Morris Agency and Irving Leonard, who were unhappy with Marsh's influence on the actor.[24] Eastwood banished Marsh from having any further influence in his career, and he was forced to sack her as his business manager via a letter sent by Frank Wells.[24] For some time after, Eastwood's publicity was handled by Jerry Pam of Gutman and Pam.[21] Throughout filming, Eastwood regularly socialized with actor Franco Nero, who was filming Texas, Adios at the time.[26]

Wallach and Eastwood flew to Madrid together and, between shooting scenes, Eastwood would relax and practice his golf swing.[27] Wallach was almost poisoned during filming when he accidentally drank from a bottle of acid that a film technician had set next to his soda bottle. Wallach mentioned this in his autobiography[28] and complained that while Leone was a brilliant director, he was very lax about ensuring the safety of his actors during dangerous scenes.[17] For instance, in one scene, where he was to be hanged after a pistol was fired, the horse underneath him was supposed to bolt. While the rope around Wallach's neck was severed, the horse was frightened a little too well. It galloped for about a mile with Wallach still mounted and his hands bound behind his back.[17] The third time Wallach's life was threatened was during the scene where he and Mario Brega—who are chained together—jump out of a moving train. The jumping part went as planned, but Wallach's life was endangered when his character attempts to sever the chain binding him to the (now dead) henchman. Tuco places the body on the railroad tracks, waiting for the train to roll over the chain and sever it. Wallach, and presumably the entire film crew, were not aware of the heavy iron steps that jutted one foot out of every box car. If Wallach had stood up from his prone position at the wrong time, one of the jutting steps could have decapitated him.[17]

The bridge in the film was reconstructed twice by sappers of the Spanish army after being rigged for on-camera explosive demolition. The first time, an Italian camera operator signalled that he was ready to shoot, which was misconstrued by an army captain as the similar-sounding Spanish word meaning "start". Nobody was injured in the erroneous mistiming. The army rebuilt the bridge while other shots were filmed. As the bridge was not a prop, but a rather heavy and sturdy structure, powerful explosives were required to destroy it.[17] Leone said that this scene was, in part, inspired by Buster Keaton's silent film The General.[11]

As an international cast was employed, actors performed in their native languages. Eastwood, Van Cleef and Wallach spoke English, and were dubbed into Italian for the debut release in Rome. For the American version, the lead acting voices were used, but supporting cast members were dubbed into English.[29] The result is noticeable in the bad synchronization of voices to lip movements on screen; none of the dialogue is completely in sync because Leone rarely shot his scenes with synchronized sound.[30] Various reasons have been cited for this: Leone often liked to play Morricone's music over a scene and possibly shout things at the actors to get them in the mood. Leone cared more for visuals than dialogue (his English was limited, at best). Given the technical limitations of the time, it would have been difficult to record the sound cleanly in most of the extremely wide shots Leone frequently used. Also, it was standard practice in Italian films at this time to shoot silently and post-dub. Whatever the actual reason, all dialogue in the film was recorded in post-production.[31]

Leone was unable to find an actual cemetery for the Sad Hill shootout scene, so the Spanish pyrotechnics chief hired 250 Spanish soldiers to build one in Carazo near Salas de los Infantes, which they completed in two days (at 41°59′25″N 3°24′29″W).[32]

By the end of filming, Eastwood had finally had enough of Leone's perfectionist directorial traits. Leone, often forcefully, insisted on shooting scenes from many different angles, paying attention to the most minute of details, which often exhausted the actors.[27] Leone, who was obese, was also a source of amusement for his excesses, and Eastwood found a way to deal with the stresses of being directed by him by making jokes about him and nicknamed him "Yosemite Sam" for his bad temperament.[27] After the film was completed, Eastwood never worked with Leone again, later turning down the role of Harmonica in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), for which Leone had personally flown to Los Angeles to give him the script. The role eventually went to Charles Bronson.[33] Years later, Leone exacted his revenge upon Eastwood during the filming of Once Upon a Time in America (1984) when he described Eastwood's abilities as an actor as being like a block of marble or wax and inferior to the acting abilities of Robert De Niro, saying, "Eastwood moves like a sleepwalker between explosions and hails of bullets, and he is always the same—a block of marble. Bobby first of all is an actor, Clint first of all is a star. Bobby suffers, Clint yawns."[34] Eastwood later gave a friend the poncho he wore in the three films, where it was hung in a Mexican restaurant in Carmel, California.[35]

Themes

Like many of his films, director Sergio Leone noted that the film is a satire of the western genre. He has noted the film's theme of emphasis on violence and the deconstruction of Old West romanticism. The emphasis on violence being seen in how the three leads (Blondie, Angel Eyes and Tuco) are introduced with various acts of violence. With Blondie, it is seen in his attempt to free Tuco which results in a gun battle. Angel Eyes is set up in a scene in which he carries out a hit on a former confederate soldier called Stevens. After getting the information he needs from Stevens he is given money to kill Baker (his employer). He then proceeds to kill Stevens and his son. Upon returning to Baker he kills him too (fulfilling his title as ‘The Bad’). Tuco is set up in a scene in which three bounty hunters try to kill him. In the film's opening scene three bounty hunters enter a building in which Tuco is hiding. After the sound of gunfire is heard Tuco escapes through a window. We then get a shot of the three corpses (fulfilling his title as ‘The Ugly’). They are all after gold and will stop at nothing until they get it. Richard T. Jameson writes “Leone narrates the search for a cache of gold by three grotesquely unprincipled men sardonically classified by the movie’s title (Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach, respectively)”.[36]

The film deconstructs Old West Romanticism by portraying the characters as antiheroes. Even the character considered by the film as ‘The Good’ can still be considered as not living up to that title in a moral sense. Critic Drew Marton describes it as a “baroque manipulation” that criticizes the American Ideology of the Western,[37] by replacing the heroic cowboy popularized by John Wayne with morally complex antiheroes.

Negative themes such as cruelty and greed are also given focus and are traits shared by the three leads in the story. Cruelty is shown in the character of Blondie in how he treats Tuco throughout the film. He is seen to sometimes be friendly with him and in other scenes double-cross him and throw him to the side. It is shown in Angel Eyes through his attitudes in the film and his tendency for committing violent acts throughout the film. For example, when he kills Stevens he also kills his son. It is also seen when he is violently torturing Tuco later in the film. It is shown in Tuco with how he shows concern for Blondie when he is heavily dehydrated but in truth, he is only keeping him alive to find the gold. It is also shown in his conversation with his brother which reveals that a life of cruelty is all he knows. Richard Aquila writes “The violent antiheroes of Italian westerns also fit into a folk tradition in southern Italy that honoured mafioso and vigilante who used any means to combat corrupt government of church officials who threatened the peasants of the Mezzogiorno”.[38]

Greed is shown in the film through its main core plotline of the three characters wanting to find the $200,000 that Bill Carson has said is buried in a grave in Sad Hill Cemetery. The main plot concerns their greed as there is a series of double crossings and changing allegiances in order to get the gold. Russ Hunter writes that the film will “stress the formation of homosocial relationships as being functional only in the pursuit of wealth”.[39] This all culminates in the film's final set-piece which takes place in the cemetery. After the death of Angel Eyes, Tuco is strung up with a rope precariously placed around his neck as Blondie leaves with his share of the money.

Many critics have also noticed the film's anti-war theme.[40][41] Taking place in the American Civil War, the film takes the viewpoint of people such as civilians, bandits, and most notably soldiers, and presents their daily hardships during the war. This is seen in how the film has a rugged and rough esthetic. The film has an air of dirtiness that can be attributed to the Civil War and in turn it affects the actions of people, showing how the war deep down has affected the lives of many people.

As Brian Jenkins states “A union cordial enough to function peacefully could not be reconstructed after a massive blood-letting that left the North crippled by depopulation and debt and the south devastated”.[42] Although not fighting in the war, the three gunslingers gradually become entangled in the battles that ensue (similar to The Great War, a film that screenwriters Luciano Vincenzoni and Age & Scarpelli had contributed to).[11] An example of this is how Tuco and Blondie blow up a bridge in order to disperse two sides of the battle. They need to clear a way to the cemetery and succeed in doing so. It is also seen in how Angel Eyes disguises himself as a union sergeant so he can attack and torture Tuco in order to get the information he needs, intertwining himself in the battle in the process.

The film as a Spaghetti Western

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly has been called the definitive Spaghetti western. Spaghetti westerns are westerns produced and directed by Italians, often in collaboration with other European countries, especially Spain and West Germany. The name ‘spaghetti western’ originally was a depreciative term, given by foreign critics to these films because they thought they were inferior to American westerns.[43] Most of the films were made with low budgets, but several still managed to be innovative and artistic, although at the time they did not get much recognition, even in Europe. The genre is unmistakably a Catholic genre, with a visual style strongly influenced by the Catholic iconography of, for instance, the crucifixion or the last supper. The outdoor scenes of many spaghetti westerns, especially those with a relatively higher budget, were shot in Spain, in particular the Tabernas desert of Almería and Colmenar Viejo and Hoyo de Manzanares. In Italy, the region of Lazio was a favourite location.

The genre expanded and became an international sensation with the success of Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars, an adaptation of a Japanese Samurai movie called Yojimbo. But a handful of westerns were made in Italy before Leone redefined the genre, and the Italians were not the first to make westerns in Europe in the sixties. But it was Leone who defined the look and attitude of the genre with his first western and the two that soon were to follow: For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Together these films are called the Dollars Trilogy. Leone's West in the latter wasn't concerned with ideas of the frontier or good vs. evil, but rather interested in how the world is unmistakably more complicated than that, and how the western world is one of kill or be killed. These films featured knifings, beatings, shootouts, or other violent action every five to ten minutes. “The issue of morality belongs to the American western,” explains Italian director Ferdinando Baldi. “The violence in our movies is more gratuitous than in the American films. There was very little morality because often the protagonist was a bad guy.” Eastwood's character is a violent and ruthless killer who murders opponents for fun and profit. Behind his cold and stony stare is a cynical mind powered by a dubious morality. Unlike earlier cowboy heroes, Eastwood's character constantly smokes a small cigar and hardly ever shaves. He wears a flat-topped hat and Mexican poncho instead of more traditional western costuming. He never introduces himself when he meets anyone, and nobody ever asks his name. Furthermore, Spaghetti Westerns redefined the western genre to fit the everchanging times of the 1960s and ’70s. Rather than portraying the traditional mythic West as an exotic and beautiful land of opportunity, hope, and redemption, they depicted a desolate and forsaken West. In these violent and troubled times, Spaghetti Westerns, with their antiheroes, ambiguous morals, brutality, and anti-Establishment themes, resonated with audiences. The films’ gratuitous violence, surrealistic style, gloomy look, and eerie sound captured the era's melancholy. It is this new approach to the genre that defined the revisionist western of the late ’70s and early ’80s; a movement started by this moral ambiguity of the spaghetti westerns, as well as a westerns placement in the context of historical events; both attributes defined and set by The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly.[44]

These films were undeniably stylish. With grandiose wide shots, and close ups that peered into the eyes and souls of the characters, The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, had the defining cinematographic techniques of the spaghetti western. This was Leone’s signature technique, using long drawn shots interspersed with extreme close ups that build tension as well as develop characters. However, Leone’s movies weren’t just influenced by style. As Quentin Tarantino notes, “there was also a realism to them: those shitty Mexican towns, the little shacks — a bit bigger to accommodate the camera — all the plates they put the beans on, the big wooden spoons. The films were so realistic, which had always seemed to be missing in the westerns of the 1930s, 40s and 50s, in the brutality and the different shades of grey and black. Leone found an even darker black and off-white. There is realism in Leone’s presentation of the Civil War in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly that was missing from all the Civil War movies that happened before him. Leone’s film, and the genre that he defined within it, shows a west that is more violent, less talky, more complex, more theatrical, and just overall more iconic through the use of music, appearing operatic as the music is an illustrative ingredient of the narrative”.[45] With a greater sense of operatic violence than their American cousins, the cycle of spaghetti westerns lasted just a few short years, but before "hanging up its spurs" in the late 70s, it completely rewrote the genre.[46]

Cinematography

In its depiction of violence, Leone used his signature long drawn and close-up style of filming, which he did by mixing extreme face shots and sweeping long shots. By doing so, Leone managed to stage epic sequences punctuated by extreme eyes and face shots, or hands slowly reaching for a holstered gun.[40] This builds up the tension and suspense by allowing the viewers to savour the performances and character reactions, creating a feeling of excitement, as well as giving Leone the freedom to film beautiful landscapes.[40] Leone also incorporated music to heighten the tension and pressure before and during the film's many gunfights.[11]

In filming the pivotal gunfights, Leone largely removes dialogue to focus more on the actions of the characters, which was important during the film's iconic Mexican standoff. This style can also be seen in one of the film's protagonists, Blondie (aka The Man with No Name), which is described by critics as more defined by his actions than his words.[37] All three characters can be seen as anti-heroes, killing for their personal gain. Leone also employed stylistic trick shooting, such as Blondie shooting the hat off a person's head and severing a hangman's noose with a well-placed shot, in many of its iconic shootouts.[47]

Releases

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly opened in Italy on 23 December 1966,[48][49] and grossed $6.3 million at that time.[50]

In the United States, A Fistful of Dollars was released 18 January 1967;[51] For a Few Dollars More was released 10 May 1967 (17 months);[52] and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was released 29 December 1967 (12 months).[9] Thus, all three of Leone's Dollars Trilogy films were released in the United States during the same year. The original Italian domestic version was 177 minutes long,[53] but the international version was shown at various lengths. Most prints, specifically those shown in the United States, had a runtime of 161 minutes, 16 minutes shorter than the Italian premiere version, but others, especially British prints, ran as short as 148 minutes.[11][54]

Critical reception

Upon release, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly received criticism for its depiction of violence.[55] Leone explains that "the killings in my films are exaggerated because I wanted to make a tongue-in-cheek satire on run-of-the-mill westerns... The west was made by violent, uncomplicated men, and it is this strength and simplicity that I try to recapture in my pictures."[56] To this day, Leone's effort to reinvigorate the timeworn Western is widely acknowledged.[57]

Critical opinion of the film on initial release was mixed, as many reviewers at that time looked down on "spaghetti westerns". In a negative review in The New York Times, critic Renata Adler said that the film "must be the most expensive, pious and repellent movie in the history of its peculiar genre."[58] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the "temptation is hereby proved irresistible to call The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, now playing citywide, The Bad, The Dull, and the Interminable, only because it is."[59] Roger Ebert, who later included the film in his list of Great Movies,[60] retrospectively noted that in his original review he had "described a four-star movie, but only gave it three stars, perhaps because it was a 'Spaghetti Western' and so could not be art."

Home media

The film was first released on VHS by VidAmerica in 1980, then Magnetic Video in 1981, CBS/Fox Video in 1983 and MGM Home Entertainment in 1990. The latter studio also released the two-cassette version in 1997 as part of the Screen Epics collection in addition to the single VHS version in 1999 as part of the Western Legends lineup.

The 1998 DVD release from MGM contained 14 minutes of scenes that were cut from the film's North American release, including a scene which explains how Angel Eyes came to be waiting for Blondie and Tuco at the Union prison camp.[54]

In 2002, the film was restored with the 14 minutes of scenes cut for US release re-inserted into the film. Clint Eastwood and Eli Wallach were brought back in to dub their characters' lines more than 35 years after the film's original release. Voice actor Simon Prescott substituted for Lee Van Cleef who had died in 1989. Other voice actors filled in for actors who had since died. In 2004, MGM released this version in a two-disc special edition DVD.[61]

Disc 1 contains an audio commentary with writer and critic Richard Schickel. Disc 2 contains two documentaries, "Leone's West" and "The Man Who Lost The Civil War", followed by the featurette "Restoring 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly'"; an animated gallery of missing sequences titled "The Socorro Sequence: A Reconstruction"; an extended Tuco torture scene; a featurette called "Il Maestro"; an audio featurette named "Il Maestro, Part 2"; a French trailer; and a poster gallery.[61]

This DVD was generally well received, though some purists complained about the re-mixed stereo soundtrack with many completely new sound effects (notably, the gunshots were replaced), with no option for the original soundtrack.[62] At least one scene that was re-inserted had been cut by Leone prior to the film's release in Italy, but had been shown once at the Italian premiere. According to Richard Schickel,[61] Leone willingly cut the scene for pacing reasons; thus, restoring it was contrary to the director's wishes.[63] MGM re-released the 2004 DVD edition in their "Sergio Leone Anthology" box set in 2007. Also included were the two other "Dollars" films, and Duck, You Sucker!. On 12 May 2009, the extended version of the film was released on Blu-ray.[30] It contains the same special features as the 2004 special edition DVD, except that it includes an added commentary by film historian Sir Christopher Frayling.[11]

The film was re-released on Blu-ray in 2014 using a new 4K remaster, featuring improved picture quality and detail but a change of color timing, resulting in the film having a more yellow hue than on previous releases.[62] It was re-released on Blu-ray and DVD by Kino Lorber Studio Classics on 15 August 2017, in a new 50th Anniversary release that featured both theatrical and extended cuts, as well as new bonus features, and an attempt to correct the yellow color timing from the earlier disc.[64]

Deleted scenes

The following scenes were originally deleted by distributors from the British and American theatrical versions of the film, but were restored after the release of the 2004 Special Edition DVD.[61]

- During his search for Bill Carson, Angel Eyes stumbles upon an embattled Confederate outpost after a massive artillery bombardment. Once there, after witnessing the wretched conditions of the survivors, he bribes a Confederate soldier (Víctor Israel, dubbed by Tom Wyner[65]) for clues about Bill Carson.

- After being betrayed by Blondie, surviving the desert on his way to civilization and assembling a good revolver from the parts of worn-out guns being sold at a general store, Tuco meets with members of his gang in a distant cave, where he conspires with them to hunt and kill Blondie.

- The sequence with Tuco and Blondie crossing the desert has been extended: Tuco mentally tortures a severely dehydrated Blondie by eating and bathing in front of him.

- Tuco, transporting a dehydrated Blondie, finds a Confederate camp whose occupants tell him that Father Ramirez's monastery is nearby.

- Tuco and Blondie discuss their plans when departing in a wagon from Father Ramirez's monastery.

- A scene where Blondie and Angel Eyes are resting by a creek when a man appears and Blondie shoots him. Angel Eyes asks the rest of his men to come out of hiding. When the five men come out, Blondie counts them (including Angel Eyes), and concludes that six is the perfect number, implying one for each bullet in his gun.

- The sequence with Tuco, Blondie and Captain Clinton has been extended: Clinton asks for their names, which they are reluctant to answer.

The footage below is all featured within supplementary features of the 2004 DVD release

- Additional footage of the sequence where Tuco is tortured by Angel Eyes's henchman was discovered. The original negative of this footage was deemed too badly damaged to be used in the theatrical cut.

- Lost footage of the missing Socorro Sequence where Tuco continues his search for Blondie in a Texican pueblo while Blondie is in a hotel room with a Mexican woman (Silvana Bacci) is reconstructed with photos and unfinished snippets from the French trailer. Also, in the documentary "Reconstructing The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly", what looks to be footage of Tuco lighting cannons before the Ecstasy of Gold sequence appears briefly. None of these scenes or sequences appear in the 2004 re-release, but are featured in the supplementary features.[30]

Music

The score is composed by frequent Leone collaborator Ennio Morricone. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly broke previous conventions on how the two had previously collaborated. Instead of scoring the film in the post-production stage, they decided to work on the themes together before shooting had started, this was so that the music helped inspire the film instead of the film inspiring the music. Leone even played the music on set and coordinated camera movements to match the music.[66] Although the score for the film is regarded as among Ennio Morricone's greatest achievements, he utilized other artists to help give the score the characteristic essence in which resonates throughout. The distinct vocals of Edda Dell'Orso can be heard permeating throughout the composition "The Ecstasy of Gold". The distinct sound of guitarist Bruno Battisti D’Amorio can be heard on the compositions ‘The Sundown’ and ‘Padre Ramirez’. Trumpet players Michele Lacerenza and Francesco Catania can be heard on ‘The Trio’.[67] The only song to feature lyrics is ‘The Story of a Soldier’; the lyrics were written by Tommie Connor.[68] Morricone's distinctive original compositions, containing gunfire, whistling (by John O'Neill), and yodelling permeate the film. The main theme, resembling the howling of a coyote (which blends in with an actual coyote howl in the first shot after the opening credits), is a two-pitch melody that is a frequent motif, and is used for the three main characters. A different instrument was used for each: flute for Blondie, ocarina for Angel Eyes, and human voices for Tuco.[69][70][71][72] The score complements the film's American Civil War setting, containing the mournful ballad, "The Story of a Soldier", which is sung by prisoners as Tuco is being tortured by Angel Eyes.[12] The film's climax, a three-way Mexican standoff, begins with the melody of "The Ecstasy of Gold" and is followed by "The Trio" (which contains a musical allusion to Morricone's previous work on For a Few Dollars More).

"The Ecstasy of Gold" is the title of a song used within The Good, The Bad and the Ugly. Composed by Morricone, it is one of his most established works within the film's score. The song has long been used within popular culture. The song features the vocals of Edda Dell'Orso,[73] an Italian female vocalist. Alongside vocals, the song features musical instruments such as the piano, drums and clarinets.[73] The song is played in the film when the character Tuco is ecstatically searching for gold, hence the song's name, "The Ecstasy of Gold".[74] Within popular culture, the song has been utilized by such artists as Metallica, who have used the song to open up their live shows and have even covered the song. Other bands such as the Ramones have featured the song in their albums and live shows. The song has also been sampled within the genre of Hip Hop, most notably by rappers such as Immortal Technique and Jay-Z. The Ecstasy of Gold has also been used ceremoniously by the Los Angeles Football Club to open home games.[74]

The main theme, also titled "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly", was a hit in 1968 with the soundtrack album on the charts for more than a year,[72] reaching No. 4 on the Billboard pop album chart and No. 10 on the black album chart.[75] The main theme was also a hit for Hugo Montenegro, whose rendition was a No. 2 Billboard pop single in 1968.[76]

In popular culture, the American new wave group Wall of Voodoo performed a medley of Ennio Morricone's movie themes, including the theme for this movie. The only known recording of it is a live performance on The Index Masters. Punk rock band the Ramones played this song as the opening for their live album Loco Live as well as in concerts until their disbandment in 1996. The British heavy metal band Motörhead played the main theme as the overture music on the 1981 "No sleep 'til Hammersmith" tour. American heavy metal band Metallica has run "The Ecstasy of Gold" as prelude music at their concerts since 1985 (except 1996–1998), and in 2007 recorded a version of the instrumental for a compilation tribute to Morricone.[77] XM Satellite Radio's The Opie & Anthony Show also opens every show with "The Ecstasy of Gold". The American punk rock band The Vandals' song "Urban Struggle" begins with the main theme. British electronica act Bomb the Bass used the main theme as one of a number of samples on their 1988 single "Beat Dis", and used sections of dialogue from Tuco's hanging on "Throughout The Entire World", the opening track from their 1991 album Unknown Territory. This dialogue along with some of the mule dialogue from Fistful of Dollars was also sampled by Big Audio Dynamite on their 1986 single Medicine Show. The main theme was also sampled/re-created by British band New Order for the album version of their 1993 single "Ruined in a Day". A song from the band Gorillaz is named "Clint Eastwood", and features references to the actor, along with a repeated sample of the theme song; the iconic yell featured in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly's score is heard at the beginning of the music video.[78]

Legacy

Re-evaluation

Despite the initial negative reception by some critics, the film has since accumulated very positive feedback. It is listed in Time's "100 Greatest Movies of the Last Century" as selected by critics Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel.[57][79] Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 97% of film critics gave the film positive reviews.[80][81][82] It is ranked #78 on the site's "Top 100 Movies of All Time".[83] The Good, the Bad and the Ugly has been described as European cinema's best representation of the Western genre film,[84] and Quentin Tarantino has called it "the best-directed film of all time" and "the greatest achievement in the history of cinema".[85] This was reflected in his votes for the 2002 and 2012 Sight & Sound magazine polls, in which he voted for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly as his choice for the best film ever made.[86] Its main music theme from the soundtrack is regarded by Classic FM as one of the most iconic themes of all time.[87] Variety magazine ranked the film number 49 on their list of the 50 greatest movies.[88] In 2002, Film4 held a poll of the 100 Greatest Movies, on which The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was voted in at number 46.[89] Premiere magazine included the film on their 100 Most Daring Movies Ever Made list.[90] Mr. Showbiz ranked the film #81 on its 100 Best Movies of All Time list.[91]

Empire magazine added The Good, the Bad and the Ugly to their Masterpiece collection in the September 2007 issue, and in their poll of "The 500 Greatest Movies", The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was voted in at number 25. In 2014, The Good the Bad and the Ugly was ranked the 47th greatest film ever made on Empire's list of "The 301 Greatest Movies Of All Time" as voted by the magazine's readers.[92] It was also placed on a similar list of 1000 movies by The New York Times.[93] In 2014, Time Out polled several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors to list their top action films. The Good, The Bad And The Ugly placed 52nd on their list.[94] BBC created an article analysing the ‘lasting legacy’ of the film, commenting about the trio scene to be “one of the most riveting and acclaimed feature films sequences of all time".[95]

In popular culture

The film's title has entered the English language as an idiomatic expression. Typically used when describing something thoroughly, the respective phrases refer to upsides, downsides and the parts that could, or should have been done better, but were not.[96]

Quentin Tarantino paid homage to the film's climactic standoff scene in his 1992 film Reservoir Dogs.[95]

The film was novelized in 1967 by Joe Millard as part of the "Dollars Western" series based on the "Man with No Name". The South Korean western movie The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008) is inspired by the film, with much of its plot and character elements borrowed from Leone's film.[97] In his introduction to the 2003 revised edition of his novel The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger, Stephen King said the film was a primary influence for the Dark Tower series, with Eastwood's character inspiring the creation of King's protagonist, Roland Deschain.[98]

In 1975, Willie Colón with Yomo Toro and Hector Lavoe, released an album titled The Good, the Bad, the Ugly. The album cover featured the three in cowboy attire.[99]

Sequel

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the last film in the Dollars Trilogy, and thus does not have an official sequel. However, screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni stated on numerous occasions that he had written a treatment for a sequel, tentatively titled Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo n. 2 (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly 2). According to Vincenzoni and Eli Wallach, the film would have been set 20 years after the original, and would have followed Tuco pursuing Blondie's grandson for the gold. Clint Eastwood expressed interest in taking part in the film's production, including acting as narrator. Joe Dante and Leone were also approached to direct and produce the film respectively. Eventually, however, the project was vetoed by Leone, as he did not want the original film's title or characters to be reused, nor did he want to be involved in another Western film.[100]

See also

References

- Marchese Ragona, Fabio (2017). "Storie di locandine – Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo". Ciak (in Italian). Vol. 10. p. 44.

- "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- "Film Releases...Print Results". Variety Insight. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Film: Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo". LUMIERE. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Variety Staff (31 December 1965). "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". Variety. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- The film was shot in three languages simultaneously: English, Italian and Spanish. Later two partially dubbed-versions were released: an English version (where Italian and Spanish dialogues were dubbed into English) and Italian version (where English and Spanish dalogues were dubbed into Italian). See Eliot (2009), p. 66

- "Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (1967) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1967)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Variety film review; 27 December 1967, page 6.

- Sir Christopher Frayling, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly audio commentary (Blu-ray version). Retrieved on 26 April 2014.

- Yezbick, Daniel (2002). "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Gale Group. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- McGilligan, Patrick (2015). Clint: The Life and Legend (updated and revised). New York: OR Books. ISBN 978-1-939293-96-1.

- Hughes, p.12

- Sergio Leone, C'era una volta il Cinema. Radio 24. Retrieved on 17 September 2014.

- Cox, 2009

- Frayling, 2000

- Hughes, p.15

- ""¡Sei attenti! ¡Tutti pronti"…". Tu Voz en Pinares (in Spanish). 2 December 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Munn, p. 59

- McGillagan (1999), p.153

- Patrick McGillagan (1999). Clint: the life and legend. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312290320 p.154

- Munn, p. 62

- McGillagan (1999), p.152

- Eliot (2009), p. 81

- Texas, Adios (Franco Nero: Back In The Saddle) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Blue Underground. 1966.

- McGillagan (1999), p.155

- Wallach, Eli (2005). The Good, the Bad and Me: In My Anecdotage, p. 255

- Cumbow (2008) p.121

- Shaffer, R.L. "The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Blu-ray Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2014. 28 May 2009

- Cumbow (2008) p.122

- Daily Mail (6 May 2005). "On the Graveyard Shift".

- McGillagan (1999), p. 158

- McGillagan (1999), p. 159

- Munn, p. 63

- James, Richard T. (March–April 1973). "SOMETHING TO DO WITH DEATH: A Fistful of Sergio Leone". Film Comment. 9 (2): 8–16. JSTOR 43450586.

- Marton, Drew. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly review". Pajiba. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2014. 22 October 2010

- Aquila, Richard (2015). The Sagebush Trail: Western Movies and Twentieth Century America. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0816531547. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Hunter, Russ (2012). "The Ecstasy of Gold: Love, Greed and Homosociality in the Dollars Trilogy". Studies in European Cinema. 9 (1): 77. doi:10.1386/seci.9.1.69_1. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Leigh, Stephen (28 November 2011). "50 Reasons Why The Good, The Bad and The Ugly Might Just Be The Greatest Film of all Time". What Culture. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Smithey, Coley. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly- Classic Film Pick". Colesmithey – Capsules. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2014. 10 February 2013

- Jenkins, Brian (2014). Lord Lyons: A Diplomat in an Age of Nationalism and War. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7735-4409-3. JSTOR j.ctt7zt1j2.11.

- "The Spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone". The Spaghetti Western Database. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Aquila, Richard (2015). The Sagebrush Trail: Western Movies and Twentieth-Century America (PDF). Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0816531547. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Frayling, Christopher. "Shooting Star". The Spectator. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Towlson, Jon. "10 great spaghetti westerns". BFI. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Wilson, Samuel. "On the Big Screen: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY (Il buono, il bruto, il cattivo, 1966)". Mondo 70: A Wild World of Cinema. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2014. 2 August 2014

- "Catalog Of Copyright Entries – Motion Pictures And Filmstrips, 1968". Archive.org. Library Of Congress, Copyright Office. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "The Good, The Bad And The Ugly – Release Info". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- Eliot (2009), p. 88

- "A Fistful of Dollars". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2014. 6 October 2014

- "For A Few Dollars More". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2014. 6 October 2014

- The Good, the Bad & the Ugly (2-Disc Collector's Edition, Reconstructing The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1967.

- The Good, the Bad & the Ugly (Additional Unseen Footage) (DVD). Los Angeles, California: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1967.

- Fritz, Ben (14 June 2004). "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". Variety.

- "Sergio Leone". Newsmakers. Gale. 2004.

- Schickel, Richard (12 February 2005). "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly". All-Time 100 Movies. Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- The New York Times, film review, 25 January 1968.

- Eliot (2009), p. 86–87

- Ebert, Roger (2006). The Great Movies II. Broadway. ISBN 0-7679-1986-6.

- The Good, the Bad & the Ugly (2-Disc Collector's Edition) (DVD). Los Angeles: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1967.

- "The Man with No Name Trilogy Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Cumbow (2008) p.103

- "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Blu-ray". Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- "Good, the Bad and the Ugly, The (live action)". CrystalAcids.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Torikian, Messrob. "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly - Expanded Edition". Soundtrack.net. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Mansell, John. "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly Review". Music from the Movies. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "The Story of A Soldier". sartana.homestead. Archived from the original on 15 April 2001. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Torikian, Messrob. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". SoundtrackNet. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- Mansell, John. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". Music from the Movies. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- McDonald, Steven. "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly : Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- Edwards, Mark (1 April 2007). "The good, the brave and the brilliant". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- Wong, Mark. "Single Review: Ennio Morricone - The Ecstasy of Gold". Rockhaq. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Doyle, Jack. "Ecstasy of Gold History". The Pop History Dig. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly charts and awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- "Hugo Montenegro > Charts & Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- "We All Love Ennio Morricone". Metallica.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- "The return of the Gorillaz". EW.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Time Magazine's All-Time 100 Movies. Time via Internet Archive. Published 12 February 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- Time Magazine (9 February 1968). "Time Magazine Review February 9, 1968". Reviews – Critics. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- Variety Staff (1966). "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". Reviews – Critics. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- Best of RT: Top 100 Movies of All Time. Archived 28 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Sergio Leone". Contemporary Authors Online. Gale. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- Turner, Rob (14 June 2004). "The Good, The Bad, And the Ugly". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009.

- Sight & Sound (2002). "How the directors and critics voted". Top Ten Poll 2002. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- "Ennio Morricone: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly". Classic FM. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Lists: 50 Best Movies of All Time, Again. Variety via Internet Archive. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- FilmFour. "Film Four's 100 Greatest Films of All Time". AMC Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- The 100 Most Daring Movies Ever Made. Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Premiere, published by AMC's FilmSite. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- The 100 Best Movies of All Time. Archived 18 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Mr. Showbiz, published by AMC's FilmSite. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "The 301 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. The New York Times via Internet Archive. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "The 100 best action movies: 60-51". Time Out. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Buckmaster, Luke. "The Lasting Legacy of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly". BBC Culture. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "KNLS Tutorial Idioms". Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- Kim Jee-woon (김지운). "The Good, the Bad, the Weird". HanCinema. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- King, Stephen (2003). The Gunslinger: Revised and Expanded Edition. Toronto: Signet Fiction. xxii. ISBN 0-451-21084-0.

- Howard J. Blumenthal The World Music CD Listener's Guide 1998 p.37

- Giusti, 2007

Bibliography

- Cox, Alex (2009). 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director's Take on the Spaghetti Western. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1-84243-304-1.

- Eliot, Marc (2009). American Rebel: The Life of Clint Eastwood. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-33688-0.

- Frayling, Christopher (2000). Sergio Leone: Something To Do With Death. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-16438-2.

- Giusti, Marco (2007). Dizionario del western all'italiana. Mondadori. ISBN 978-88-04-57277-0.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

- Cumbow, Robertl (2008). The Films of Sergio Leone. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6041-4.

Further reading

- Charles Leinberger, Ennio Morricone's The Good, The Bad And The Ugly: A Film Score Guide. Scarecrow Press, 2004.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (film). |

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly on IMDb

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at AllMovie

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at the TCM Movie Database

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at Metacritic