Cimabue

Cimabue (US: /ˌtʃiːməˈbuːeɪ, -mɑːˈ-/,[1][2] Italian: [tʃimaˈbuːe], Ecclesiastical Latin: [tʃiˈmabu.e]; c. 1240 – 1302),[3] also known as Cenni di Pepo[4] or Cenni di Pepi,[5] was an Italian painter and designer of mosaics from Florence.

Although heavily influenced by Byzantine models, Cimabue is generally regarded as one of the first great Italian painters to break from the Italo-Byzantine style.[6] While medieval art then was scenes and forms that appeared relatively flat and highly stylized, Cimabue's figures were depicted with more advanced lifelike proportions and shading than other artists of his time. According to Italian painter and historian Giorgio Vasari, Cimabue was the teacher of Giotto,[3] the first great artist of the Italian Proto-Renaissance. However, many scholars today tend to discount Vasari's claim by citing earlier sources that suggest otherwise.[7]

Life

%2C_tavola_di_san_francesco%2C_museo_della_porziuncola.jpg)

Little is known about Cimabue's early life. One source that recounts his career is Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, but its accuracy is uncertain.

He was born in Florence and died in Pisa. Hayden Maginnis speculates that he could have trained in Florence under masters who were culturally connected to Byzantine art.

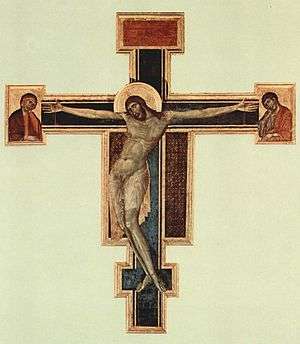

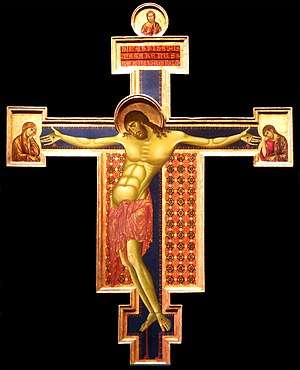

Italian art historian Pietro Toesca attributed the Crucifixion in the church of San Domenico in Arezzo to Cimabue, dating around 1270, making it the earliest known attributed work that departs from the Byzantine style.[8] Cimabue's Christ is bent, and the clothes have the golden striations that were introduced by Coppo di Marcovaldo.

Around 1272, Cimabue is documented as being present in Rome,[9] and a little later he made another Crucifix for the Florentine church of Santa Croce.[10] Now restored, having been damaged by the 1966 Arno River flood, the work was larger and more advanced than the one in Arezzo, with traces of naturalism perhaps inspired by the works of Nicola Pisano.

According to Vasari, Cimabue, while travelling from Florence to Vespignano, came upon the 10-year-old Giotto (c. 1277) drawing his sheep with a rough rock upon a smooth stone. He asked if Giotto would like to come and stay with him, which the child accepted with his father's permission.[11] Vasari elaborates that during Giotto's apprenticeship, he allegedly painted a fly on the nose of a portrait Cimabue was working on; the teacher attempted to sweep the fly away several times before he understood his pupil's prank.[11] Many scholars now discount Vasari's claim that he took Giotto as his pupil, citing earlier sources that suggest otherwise.[7]

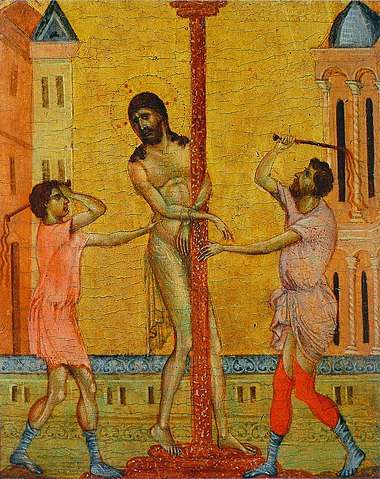

Around 1280, Cimabue painted the Maestà, originally displayed in the church of San Francesco at Pisa, but now at the Louvre.[12] This work established a style that was followed subsequently by numerous artists, including Duccio di Buoninsegna in his Rucellai Madonna (in the past, wrongly attributed to Cimabue) as well as Giotto. Other works from the period, which were said to have heavily influenced Giotto, include a Flagellation (Frick Collection), mosaics for the Baptistery of Florence (now largely restored), the Maestà at the Santa Maria dei Servi in Bologna and the Madonna in the Pinacoteca of Castelfiorentino. A workshop painting, perhaps assignable to a slightly later period, is the Maestà with Saints Francis and Dominic currently housed in the Uffizi.

During the pontificate of Pope Nicholas IV, the first Franciscan pope,[13] Cimabue worked in Assisi.[14] At Assisi, in the transept of the Lower Basilica of San Francesco, he created a fresco named Madonna with Child Enthroned, Four Angels and St Francis. The left portion of this fresco is lost, but it may have shown St Anthony of Padua (the authorship of the painting has been recently disputed for technical and stylistic reasons). Cimabue was subsequently commissioned to decorate the apse and the transept of the Upper Basilica of Assisi, in the same period of time that Roman artists were decorating the nave. The cycle he created there comprises scenes from the Gospels, the lives of the Virgin Mary, St Peter and St Paul. The paintings are now in poor condition because of oxidation of the brighter colours that were used by the artist.

The Maestà of Santa Trinita, dated to c. 1290–1300, which was originally painted for the church of Santa Trinita in Florence, is now in the Uffizi Gallery. The softer expression of the characters suggests that it was influenced by Giotto, who was by then already active as a painter.[15]

Cimabue spent the last period of his life, 1301 to 1302, in Pisa. There, he was commissioned to finish a mosaic of Christ Enthroned, originally begun by Maestro Francesco, in the apse of the city's cathedral. Cimabue was to create the part of the mosaic depicting St John the Evangelist, which remains the sole surviving work documented as being by the artist.[16] Cimabue died around 1302.[17]

Character

According to Vasari, quoting a contemporary of Cimabue, "Cimabue of Florence was a painter who lived during the author's own time, a nobler man than anyone knew but he was as a result so haughty and proud that if someone pointed out to him any mistake or defect in his work, or if he had noted any himself... he would immediately destroy the work, no matter how precious it might be." [18]

The nickname Cimabue translates as "bull-head" but also possibly as "one who crushes the views of others", from the Latin word cimare, meaning "top", "shear", and "blunt". The conclusion for the second meaning is drawn from similar commentaries on Dante, who was also known "for being contemptuous of criticism".[19]

Legacy

History has long regarded Cimabue as the last of an era that was overshadowed by the Italian Renaissance. As early as 1543, Vasari wrote of Cimabue, "Cimabue was, in one sense, the principal cause of the renewal of painting," with the qualification that, "Giotto truly eclipsed Cimabue's fame just as a great light eclipses a much smaller one."[18]

In Canto XI of his Purgatorio, Dante laments Cimabue's quick loss of public interest in the face of Giotto's revolution in art:[20]

O vanity of human powers,

how briefly lasts the crowning green of glory,

unless an age of darkness follows!

In painting Cimabue thought he held the field

but now it's Giotto has the cry,

so that the other's fame is dimmed.

Market

On 27 October 2019, Christ Mocked, discovered the previous month in northern France, in the kitchen of an elderly French woman, sold for €24m (£20m; $26.6m) at auction, setting a new record. The sale price was four times the estimate. Acteon Auction House said the sum, paid by an anonymous buyer from northern France, was a new world record for a medieval painting sold at auction.[21]

Gallery

Virgin Enthroned with Angels, c. 1280, Louvre, Paris

Virgin Enthroned with Angels, c. 1280, Louvre, Paris

The Last Supper

The Last Supper Madonna di Castelfiorentino, 1280s

Madonna di Castelfiorentino, 1280s- Maestà, Santa Maria dei Servi

_-_WGA04921.jpg) Madonna Enthroned with the Child, St Francis and four Angels (detail)

Madonna Enthroned with the Child, St Francis and four Angels (detail) Flagellation

Flagellation Maestà of Santa Trinita, (detail) Prophet

Maestà of Santa Trinita, (detail) Prophet_-_WGA04929.jpg) Detail of the Santa Croce Crucifix showing Apostle John

Detail of the Santa Croce Crucifix showing Apostle John Detail of mosaic Christ enthroned with the Virgin and St John showing St. John the Evangelist

Detail of mosaic Christ enthroned with the Virgin and St John showing St. John the Evangelist

Christ Mocked, sold at auction for €24m in 2019

Christ Mocked, sold at auction for €24m in 2019

References

Citations

- "Cimabue". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Cimabue". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Giorgio Vasari. Lives of the Artists. Translated with an introduction and notes by J.C. and P Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press (Oxford World’s Classics), 1991, pp. 7–14. ISBN 978-0-19-953719-8.

- Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms. BCA. p. 38.

- J. A. Crowe; G. B. Calvalcaselle (1975). A History of Painting in Italy; Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. 1. AMS Press. p. 202.

- Fred Kleiner (2008). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History. 2. Cengage Learning EMEA. p. 502.

- Hayden B.J. Maginnis (2004). "In Search of an Artist". In Anne Derbes; Mark Sandona (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Giotto. Cambridge. pp. 12–13.

- Paoletti, John T.; Radke, Gary M. (2005). Art in Renaissance Italy. Laurence King Publishing. p. 51.

- Van Vechten Brown, Alice; Rankin, William (1914). A Short History of Italian Painting. J.M. Dent & Sons, ltd. p. 41.

- Brink, Joel (October 1978). "Carpentry and Symmetry in Cimabue's Santa Croce Crucifix". The Burlington Magazine. Volume 120 (No. 907).

- Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. pp. 82, 85. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- Maxwell, Virginia; Leviton, Alex; Pettersen, Leif (2010). Tuscany & Umbria. Lonely Planet. p. 364.

- Havely, Nick (2004). Dante and the Franciscans: Poverty and the Papacy in the 'Commedia'. Cambridge University Press. p. 39.

- Brooke, Rosalind B. (2006). The Image of St. Francis: Responses to Sainthood in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 352.

- Paoletti, John T.; Radke, Gary M. (2005). Art in Renaissance Italy. Laurence King Publishing. p. 85.

- White, John (26 May 1993). Art and architecture in Italy 1250-1400 (3rd Revised ed.). Yale University Press. p. 175. ISBN 9707250208.

- Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 223–224.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1991). Lives of the Artists, 1550. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-19-281754-X.

- Gibbs, Robert. "Cimabue". www.oxfordartonline.com. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Purgatio XI, cited in the Cenni di Petro Cimabue article in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Masterpiece found in French kitchen fetches €24m". 27 October 2019 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

Sources

- Adams, Laurie Schneider (2001). Italian Renaissance Art. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 420. ISBN 0-8133-3690-2.

- Rossetti, William Michael (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1987). Lives of the Artists. Translated by George Bull. Penguin Classics. ISBN 9780140445008.

- Vaughn, William (2000). Encyclopedia of Artists. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-521572-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cimabue. |

- Cimabue. Pictures and Biography

- Cimabue Santa Trinita Madonna (1280–1290). A video discussion about the painting from smarthistory.khanacademy.org