OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a collaborative project to create a free editable map of the world. The geodata underlying the map is considered the primary output of the project. The creation and growth of OSM has been motivated by restrictions on use or availability of map data across much of the world, and the advent of inexpensive portable satellite navigation devices.[6]

OpenStreetMap's logo featuring a magnifier focused on geographic information. | |

OSM homepage | |

Type of site | Collaborative mapping |

|---|---|

| Available in |

|

| Owner | OpenStreetMap Community. Project support by OpenStreetMap Foundation[2] |

| Created by | Steve Coast (User page in OSM) |

| URL | openstreetmap.org |

| Alexa rank | |

| Commercial | No |

| Registration | Required for contributors, not required for viewing |

| Users | 6,450,058 [4] |

| Launched | 9 August 2004[5] |

| Current status | Active (click to see in detail) |

Content license | ODbL |

Created by Steve Coast in the UK in 2004, it was inspired by the success of Wikipedia and the predominance of proprietary map data in the UK and elsewhere.[7][8] Since then, it has grown to over two million registered users.[9] Users may collect data using manual survey, GPS devices, aerial photography, and other free sources. This crowdsourced data is then made available under the Open Database License. The site is supported by the OpenStreetMap Foundation, a non-profit organisation registered in England and Wales.

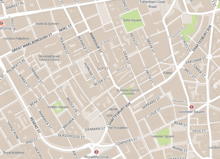

The data from OSM can be used in various ways including production of paper maps and electronic maps (similar to Google Maps, for example), geocoding of address and place names, and route planning.[10] Prominent users include Facebook, Wikimedia Maps, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon Logistics, Uber, Craigslist, Snapchat, OsmAnd, Geocaching, MapQuest Open, JMP statistical software, and Foursquare. Many users of GPS devices use OSM data to replace the built-in map data on their devices.[11] OpenStreetMap data has been favourably compared with proprietary datasources,[12] although in 2009 data quality varied across the world.[13][14]

History

.jpg)

Steve Coast founded the project in 2004, initially focusing on mapping the United Kingdom. In the UK and elsewhere, government-run and tax-funded projects like the Ordnance Survey created massive datasets but failed to freely and widely distribute them. The first contribution, made in the British city of London in 2005,[15] was thought to be a road by the Directions Mag.[16]

In April 2006, the OpenStreetMap Foundation was established to encourage the growth, development and distribution of free geospatial data and provide geospatial data for anybody to use and share. In December 2006, Yahoo! confirmed that OpenStreetMap could use its aerial photography as a backdrop for map production.[17]

In April 2007, Automotive Navigation Data (AND) donated a complete road data set for the Netherlands and trunk road data for India and China to the project[18] and by July 2007, when the first OSM international The State of the Map conference was held, there were 9,000 registered users. Sponsors of the event included Google, Yahoo! and Multimap. In October 2007, OpenStreetMap completed the import of a US Census TIGER road dataset.[19] In December 2007, Oxford University became the first major organisation to use OpenStreetMap data on their main website.[20]

Ways to import and export data have continued to grow – by 2008, the project developed tools to export OpenStreetMap data to power portable GPS units, replacing their existing proprietary and out-of-date maps.[21] In March, two founders announced that they have received venture capital funding of €2.4 million for CloudMade, a commercial company that uses OpenStreetMap data.[22] In November 2010, Bing changed their licence to allow use of their satellite imagery for making maps.[23]

In 2012, the launch of pricing for Google Maps led several prominent websites to switch from their service to OpenStreetMap and other competitors.[24] Chief among these were Foursquare and Craigslist, which adopted OpenStreetMap, and Apple, which ended a contract with Google and launched a self-built mapping platform using TomTom and OpenStreetMap data.[25]

Map production

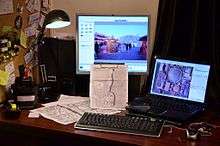

Map data is collected from scratch by volunteers performing systematic ground surveys using tools such as a handheld GPS unit, a notebook, digital camera, or a voice recorder. The data is then entered into the OpenStreetMap database. Mapathon competition events are also held by OpenStreetMap team and by non-profit organisations and local governments to map a particular area.

The availability of aerial photography and other data from commercial and government sources has added important sources of data for manual editing and automated imports. Special processes are in place to handle automated imports and avoid legal and technical problems.[26]

Software for editing maps

Editing of maps can be done using the default web browser editor called iD, an HTML5 application using D3.js and written by Mapbox,[27] which was originally financed by the Knight Foundation.[28] The earlier Flash-based application Potlatch is retained for intermediate-level users. JOSM and Merkaartor are more powerful desktop editing applications that are better suited for advanced users.

Vespucci is the first full-featured editor for Android; it was released in 2009.[29] StreetComplete is an Android app launched in 2016,[30] which allows users without any OpenStreetMap knowledge to answer simple quests for existing data in OpenStreetMap, and thus contribute data.[31] Maps.me is a mobile application (which runs on both Android and iOS) offering offline maps which also includes a limited OSM data editor.[32] Go Map!! is an iOS app that lets users create and edit information in OpenStreetMap. Pushpin is another iOS app that lets users add POI on the go.

Contributors

The project has a geographically diverse user-base, due to emphasis of local knowledge and ground truth in the process of data collection. Many early contributors were cyclists who survey with and for bicyclists, charting cycleroutes and navigable trails.[33] Others are GIS professionals who contribute data with Esri tools.[34] Contributors are predominately men, with only 3–5% being women.[35]

By August 2008, shortly after the second The State of the Map conference was held, there were over 50,000 registered contributors; by March 2009, there were 100,000 and by the end of 2009 the figure was nearly 200,000. In April 2012, OpenStreetMap cleared 600,000 registered contributors.[36] On 6 January 2013, OpenStreetMap reached one million registered users.[37] Around 30% of users have contributed at least one point to the OpenStreetMap database.[38]

Surveys and personal knowledge

Ground surveys are performed by a mapper, on foot, bicycle, or in a car, motorcycle, or boat. Map data are usually collected using a GPS unit, although this is not strictly necessary if an area has already been traced from satellite imagery.

Once the data has been collected, it is entered into the database by uploading it onto the project's website together with appropriate attribute data. As collecting and uploading data may be separated from editing objects, contribution to the project is possible without using a GPS unit.

Some committed contributors adopt the task of mapping whole towns and cities, or organising mapping parties to gather the support of others to complete a map area. A large number of less active users contribute corrections and small additions to the map.

Street-level image data

In addition to several different sets of satellite image backgrounds available to OSM editors, data from several street-level image platforms are available as map data photo overlays: Bing Streetside 360° image tracks, and the open and crowdsourced Mapillary and OpenStreetCam platforms, generally smartphone and other windshield-mounted camera images. Additionally, a Mapillary traffic sign data layer can be enabled; it is the product of user-submitted images.[39]

Government data

Some government agencies have released official data on appropriate licences. This includes the United States, where works of the federal government are placed under public domain.[40]

In the United States, OSM uses Landsat 7 satellite imagery, Prototype Global Shorelines from NOAA, and TIGER from the Census. In the UK, some Ordnance Survey OpenData is imported, while Natural Resources Canada's CanVec vector data and GeoBase provide landcover and streets.

Out-of-copyright maps can be good sources of information about features that do not change frequently. Copyright periods vary, but in the UK Crown copyright expires after 50 years and hence Ordnance Survey maps until the 1960s can legally be used. A complete set of UK 1 inch/mile maps from the late 1940s and early 1950s has been collected, scanned, and is available online as a resource for contributors.

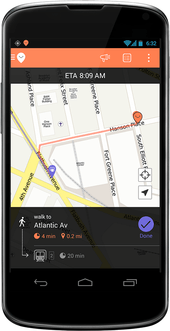

Route planning

In February 2015, OpenStreetMap added route planning functionality to the map on its official website. The routing uses external services, namely OSRM, GraphHopper and MapQuest.[41]

There are other routing providers and applications listed in the official Routing wiki.

Map usage

Software for viewing maps

- Web browser

- Data provided by the OpenStreetMap project can be viewed in a web browser with JavaScript support via Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) on its official website. The basic map views offered are: Standard, Cycle map, Transport map and Humanitarian. Map display and category options are available using OpenStreetBrowser.

- OsmAnd

- OsmAnd is free software for Android and iOS mobile devices that can use offline vector data from OSM. It also supports layering OSM vector data with prerendered raster map tiles from OpenStreetMap and other sources.

- Maps.me

- Maps.me is free software for Android and iOS mobile devices that provides offline maps based on OSM data.

- GNOME Maps

- GNOME Maps is a graphical front-end written in JavaScript and introduced in GNOME 3.10. It provides a mechanism to find the user's location with the help of GeoClue, finds directions via GraphHopper and it can deliver a list as answer to queries.

- Marble

- Marble is a KDE virtual globe application which received support for OpenStreetMap.

- FoxtrotGPS

- FoxtrotGPS is a GTK+-based map viewer, that is especially suited to touch input.[42] It is available in the SHR or Debian repositories.[43]

The web site OpenStreetMap.org provides a slippy map interface based on the Leaflet JavaScript library (and formerly built on OpenLayers), displaying map tiles rendered by the Mapnik rendering engine, and tiles from other sources including OpenCycleMap.org.[44]

Custom maps can also be generated from OSM data through various software including Jawg Maps, Mapnik, Mapbox Studio, Mapzen's Tangrams.

OpenStreetMap maintains lists of online and offline routing engines available, such as the Open Source Routing Machine.[45] OSM data is popular with routing researchers, and is also available to open-source projects and companies to build routing applications (or for any other purpose).

Humanitarian aid

The 2010 Haiti earthquake has established a model for non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to collaborate with international organisations. OpenStreetMap and Crisis Commons volunteers using available satellite imagery to map the roads, buildings and refugee camps of Port-au-Prince in just two days, building "the most complete digital map of Haiti's roads".[47][48][49]

The resulting data and maps have been used by several organisations providing relief aid, such as the World Bank, the European Commission Joint Research Centre, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, UNOSAT and others.[50][51][52][51][53]

NGOs, like the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team and others, have worked with donors like United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to map other parts of Haiti and parts of many other countries, both to create map data for places that were blank, and to engage and build capacity of local people.[54]

After Haiti, the OpenStreetMap community continued mapping to support humanitarian organisations for various crises and disasters. After the Northern Mali conflict (January 2013), Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines (November 2013), and the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa (March 2014), the OpenStreetMap community has shown it can play a significant role in supporting humanitarian organisations.[55][56][57][58]

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team acts as an interface between the OpenStreetMap community and the humanitarian organisations.

Along with post-disaster work, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team has worked to build better risk models and grow the local OpenStreetMap communities in multiple countries including Uganda, Senegal, the Democratic Republic of the Congo in partnership with the Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières, World Bank, and other humanitarian groups.[59][60][61]

Scientific research

OpenStreetMap data was used in scientific studies. For example, road data was used for research of remaining roadless areas.[62]

"State of the Map" annual conference

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to OpenStreetMap. |

Since 2007, the OSM community has held an annual, international conference called State of the Map.

Venues have been:

- 2007: Manchester, UK[63]

- 2008: Limerick, Ireland[64]

- 2009: Amsterdam, Netherlands[65]

- 2010: Girona, Spain[66]

- 2011: Denver, USA[67]

- 2012: Tokyo, Japan[68]

- 2013: Birmingham, UK[69]

- 2014: Buenos Aires, Argentina[70]

- 2015: (no State of the Map was held in 2015)[71]

- 2016: Brussels, Belgium[72]

- 2017: Aizuwakamatsu, Japan[73]

- 2018: Milan, Italy[74]

- 2019: Heidelberg, Germany

- 2020: Online conference (July 4–5).[75] (The event was originally planned to take place in Cape Town, South Africa, has been turned into an online conference due to the COVID-19 pandemic)

There are also various national, regional and continental SotM conferences, such as State of the Map U.S., SotM Baltics and SotM Asia.[76]

Legal aspects

Licensing terms

OpenStreetMap data was originally published under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (CC BY-SA) with the intention of promoting free use and redistribution of the data. In September 2012, the licence was changed to the Open Database Licence (ODbL) published by Open Data Commons (ODC) in order to more specifically define its bearing on data rather than representation.[77][78]

As part of this relicensing process, some of the map data was removed from the public distribution. This included all data contributed by members that did not agree to the new licensing terms, as well as all subsequent edits to those affected objects. It also included any data contributed based on input data that was not compatible with the new terms. Estimates suggested that over 97% of data would be retained globally, however certain regions would be affected more than others, such as in Australia where 24 to 84% of objects would be retained, depending on the type of object.[79] Ultimately, more than 99% of the data was retained, with Australia and Poland being the countries most severely affected by the change.[80]

All data added to the project needs to have a licence compatible with the Open Database Licence. This can include out-of-copyright information, public domain or other licences. Contributors agree to a set of terms which require compatibility with the current licence. This may involve examining licences for government data to establish whether it is compatible.

Software used in the production and presentation of OpenStreetMap data is available from many different projects and each may have its own licensing. The application — what users access to edit maps and view changelogs, is powered by Ruby on Rails. The application also uses PostgreSQL for storage of user data and edit metadata. The default map is rendered by Mapnik, stored in PostGIS, and powered by an Apache module called mod_tile. Certain parts of the software, such as the map editor Potlatch2, have been made available as public domain.[81]

Commercial data contributions

Some OpenStreetMap data is supplied by companies that choose to freely license either actual street data or satellite imagery sources from which OSM contributors can trace roads and features.

Notably, Automotive Navigation Data provided a complete road data set for Netherlands and details of trunk roads in China and India. In December 2006, Yahoo! confirmed that OpenStreetMap was able to make use of their vertical aerial imagery and this photography was available within the editing software as an overlay. Contributors could create their vector based maps as a derived work, released with a free and open licence,[17] until the shutdown of the Yahoo! Maps API on 13 September 2011.[82] In November 2010, Microsoft announced that the OpenStreetMap community could use Bing vertical aerial imagery as a backdrop in its editors.[83] For a period from 2009 to 2011, NearMap Pty Ltd made their high-resolution PhotoMaps (of major Australian cities, plus some rural Australian areas) available for deriving OpenStreetMap data under a CC BY-SA licence.[84]

In June 2018, the Microsoft Bing team announced a major contribution of 125 million U.S. building footprints to the project – four times the number contributed by users and government data imports.[85][86]

Operation

While OpenStreetMap aims to be a central data source, its map rendering and aesthetics are meant to be only one of many options, some which highlight different elements of the map or emphasise design and performance.

Data format

OpenStreetMap uses a topological data structure, with four core elements (also known as data primitives):

- Nodes are points with a geographic position, stored as coordinates (pairs of a latitude and a longitude) according to WGS 84.[87] Outside of their usage in ways, they are used to represent map features without a size, such as points of interest or mountain peaks.

- Ways are ordered lists of nodes, representing a polyline, or possibly a polygon if they form a closed loop. They are used both for representing linear features such as streets and rivers, and areas, like forests, parks, parking areas and lakes.

- Relations are ordered lists of nodes, ways and relations (together called "members"), where each member can optionally have a "role" (a string). Relations are used for representing the relationship of existing nodes and ways. Examples include turn restrictions on roads, routes that span several existing ways (for instance, a long-distance motorway), and areas with holes.

- Tags are key-value pairs (both arbitrary strings). They are used to store metadata about the map objects (such as their type, their name and their physical properties). Tags are not free-standing, but are always attached to an object: to a node, a way or a relation. A recommended ontology of map features (the meaning of tags) is maintained on a wiki. New tagging schemes can always be proposed by a popular vote of a written proposal in OpenStreetMap wiki, however, there is no requirement to follow this process. There are over 89 million different kinds of tags in use as of June 2017.[88]

Data storage

The OSM data primitives are stored and processed in different formats.

The main copy of the OSM data is stored in OSM's main database. The main database is a PostgreSQL database with PostGIS extension, which has one table for each data primitive, with individual objects stored as rows.[89][90] All edits happen in this database, and all other formats are created from it.

For data transfer, several database dumps are created, which are available for download. The complete dump is called planet.osm. These dumps exist in two formats, one using XML and one using the Protocol Buffer Binary Format (PBF).

Popular services

A variety of popular services incorporate some sort of geolocation or map-based component. Notable services using OSM for this include:

- Apple Inc. unexpectedly created an OpenStreetMap-based map for iPhoto for iOS on 7 March 2012, and launched the maps without properly citing the data source – though this was corrected in 1.0.1. OpenStreetMap is one of the many cited sources for Apple's custom maps in iOS 6, though the majority of map data is provided by TomTom.

- Craigslist switched to OpenStreetMap in 2012, rendering their own tiles based on the data.[91]

- Ballardia (games developer) launched World of the Living Dead: Resurrection in October 2013,[92] which has incorporated OpenStreetMap into its game engine, along with census information to create a browser-based game mapping over 14,000 square kilometres of greater Los Angeles and survival strategy gameplay. Its previous incarnation had used Google Maps,[93] which had proven incapable of supporting high volumes of players, so during 2013 they shut down the Google Maps version and ported the game to OSM.[94]

- Facebook uses the map directly in its website/mobile app (depending on the zoom level, the area and the device).

- Flickr uses OpenStreetMap data for various cities around the world, including Baghdad, Beijing, Kabul, Santiago, Sydney and Tokyo.[95][96][97] In 2012, the maps switched to use Nokia data primarily, with OSM being used in areas where the commercial provider lacked performance.[98]

- Foursquare started using OpenStreetMap via Mapbox's rendering and infrastructure of OSM.[99]

- Geotab uses OpenStreetMap data in their Vehicle Tracking Software platform, MyGeotab.[100]

- Hasbro, the toy company behind the real estate-themed board game Monopoly, launched Monopoly City Streets, a massively multiplayer online game (MMORPG) which allowed players to "buy" streets all over the world. The game used map tiles from Google Maps and the Google Maps API to display the game board, but the underlying street data was obtained from OpenStreetMap.[101] The online game was a limited time offering, its servers were shut down in the end of January 2010.[102]

- MapBox

- MapQuest announced a service based on OpenStreetMap in 2010, which eventually became MapQuest Open.[103]

- Mapworks incorporated the OSM Data set for rendering under a vector publication method. This allows basic GIS analysis capabilities to be performed at web clients supporting HTML5.

- Moovit uses maps based on OpenStreetMap in their free mobile application for public transit navigation.[104]

- Niantic switched to OSM based maps from Google Maps on 1 December 2017 for their games Ingress and Pokémon Go.[105][106]

- Nominatim[107][108] (from the Latin, 'by name') is a tool to search OSM data by name and address (geocoding) and then to generate synthetic addresses of OSM points (reverse geocoding).

- OpenGeofiction is a geofiction website that uses the OpenStreetMap software but instead of the Earth, it has the map of a fictional planet.[109] When signing up, users can only edit certain countries specifically marked as available for everyone.[110][111] After at least seven days (pending approval from staff), the user can apply for a country (or sometimes part of a country) to edit.[112] Users are expected to keep their parts of the map realistic (ie, earthlike, set in the present day and no Science fiction or fantasy elements) and not copy anything from OpenStreetMap (as that would be copyright infringement).[113] They also have a wiki but officially, the staff prefers that users concentrate on the map and use the wiki to describe things on the map (and certain things impossible to put on the map like national flags) and for collaboration.[114] The site also has a "user diary" section which is basically a shared blog.[115]

- Snapchat's June 2017 update introduced its Snap Map with data from Mapbox, OpenStreetMap, and DigitalGlobe.[116]

- Strava switched to OpenStreetMap rendered and hosted by Mapbox from Google Maps in July 2015.[117]

- Tableau has integrated OSM for all their mapping needs. It has been integrated in all of their products.

- TCDD Taşımacılık uses OpenStreetMap as a location map on passenger seats on YHTs.

- Tesla Smart Summon feature released widely in US in October 2019 uses OSM data to navigate vehicles in private parking areas autonomously (without a safety driver)[118]

- Webots uses OpenStreetMap data to create virtual environment for autonomous vehicle simulations.[119]

- Wikimedia projects uses OpenStreetMap as a locator map for cities and travel points of interest.

- Wikipedia uses OpenStreetMap data to render custom maps used by the articles. Many languages are included in the WIWOSM project (Wikipedia Where in OSM) which aims to show OSM objects on a slippy map, directly visible on the article page.[120]

See also

- Building information modeling

- Collaborative mapping

- Comparison of web map services

- Counter-mapping

- Neogeography

- Turn-by-turn navigation

- Volunteered geographic information

- Other collaborative mapping projects

- HERE Map Creator

- Google Map Maker

- Wikimapia

- Yandex.Map editor

- Mobile applications

References

- "openstreetmap-website/config/locales at master". Retrieved 30 September 2019 – via GitHub.

- "FAQ". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "openstreetmap.org Competitive Analysis, Marketing Mix and Traffic". Alexa. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "OpenStreetMap Statistics". OpenStreetMap. OpenStreetMap Foundation. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "History of OpenStreetMap". OpenStreetMap wiki. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Anderson, Mark (18 October 2006). "Global Positioning Tech Inspires Do-It-Yourself Mapping Project". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Lardinois, Frederic (9 August 2014). "For the Love of Mapping Data" (Interview). TechCrunch. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Ramm, Frederick; Topf, Jochen; Chilton, Steve (2011). OpenStreetMap: Using and Enhancing the Free Map of the World. UIT Cambridge.

- Neis, Pascal; Zipf, Alexander (2012), "Analyzing the Contributor Activity of a Volunteered Geographic Information Project — the Case of OpenStreetMap", ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 1 (2): 146–165, Bibcode:2012IJGI....1..146N, doi:10.3390/ijgi1020146

- Maier, Gunther (2014). "OpenStreetMap, the Wikipedia Map". Region. 1 (1): R3–R10. doi:10.18335/region.v1i1.70.

- "OSM Maps on Garmin". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- Zielstra, Dennis. "Comparing Shortest Paths Lengths of Free and Proprietary Data for Effective Pedestrian Routing in Street Networks" (PDF). University of Florida, Geomatics Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- Haklay, M. (2010). "How good is volunteered geographical information? A comparative study of OpenStreetMap and Ordnance Survey datasets" (PDF). Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 37 (4): 682–703. doi:10.1068/b35097.

- Coleman, D. (2013). "Potential Contributions and Challenges of VGI for Conventional Topographic Base-Mapping Programs". In Sui, D.; Elwood, S; Goodchild, M. (eds.). Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice. New York, London: Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. pp. 245–264. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4587-2. ISBN 978-94-007-4586-5.

- Coast, Steve. "Changest #1 on OpenStreetMap". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Sinton, Diana (6 April 2016). "OSM: The simple map that became a global movement". The Directions Mag. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Coast, Steve (4 December 2006). "Yahoo! aerial imagery in OSM". OpenGeoData. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Coast, Steve (4 July 2007). "AND donate entire Netherlands to OpenStreetMap". OpenGeoData. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Willis, Nathan (11 October 2007). "OpenStreetMap project imports US government maps". Linux.com. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Batty, Peter (3 December 2007). "Oxford University using OpenStreetMap data". Geothought. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Fairhurst, Richard (13 January 2008). "Cycle map on your GPS". Système D. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "We're funded!". CloudMade. 17 March 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "Bing engages open maps community". 23 November 2010.

- Fossum, Mike (20 March 2012). "Websites Bypassing Google Maps Due to Fees". Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Ingraham, Nathan (11 June 2012). "Apple using TomTom and OpenStreetMap data in iOS 6 Maps app". Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "Import/Guidelines". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

The import guidelines, along with the Automated Edits code of conduct, should be followed when importing data into the OpenStreetMap database as they embody many lessons learned throughout the history of OpenStreetMap. Imports should be planned and executed with more care and sensitive than other edits, because poor imports can have significant impacts on both existing data and local mapping community.

- Saman Bemel Benrud (31 January 2013). "A New Editor for OpenStreetMap: iD". Mapbox.

- Barth, Alex (20 May 2013). "Collaborating to improve OpenStreetMap infrastructure".

- "Welcome to Vespucci". Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Zwick, Tobias (21 February 2018), StreetComplete: Surveyor app for Android, retrieved 21 February 2018

- "StreetComplete – OpenStreetMap Wiki". wiki.openstreetmap.org. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Map editor". maps.me. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Key and More Info". OpenCycleMap. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Vines, Emily. "Esri Releases ArcGIS Editor for OpenStreetMap". Esri. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- "Gender and Experience-Related Motivators for Contributing to OpenStreetMap". https://publik.tuwien.ac.at/files/PubDat_218905.pdf

- "Stats". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- Wood, Harry. "1 million OpenStreetMappers". OpenGeoData. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Neis, Pascal. "The OpenStreetMap Contributors Map aka Who's around me?". Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Fast Traffic Sign Mapping with OpenStreetMap and Mapillary". The Mapillary Blog. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- See Copyright status of work by the U.S. government for more details.

- "Routing on OpenStreetMap.org | OpenStreetMap Blog". Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "FoxtrotGPS homepage".

- "FoxtrotGPS in Debian".

- "OpenCycleMap.org – the OpenStreetMap Cycle Map". opencyclemap.org.

- Filney, Klint (11 November 2013). "Out in the Open: How to Get Google Maps Directions Without Google". Wired. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- "OpenStreetMap Activities for Typhoon Haiyan (2013)". Neis-one.org. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- Forrest, Brady (1 February 2010). "Technology Saves Lives In Haiti". Forbes.com. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "CrisisCommons". CrisisCommons.

- "Digital Help for Haiti". The New York Times. 27 January 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "WikiProject Haiti". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Batty, Peter (14 February 2010). "OpenStreetMap in Haiti – video".

- Turner, Andrew (3 February 2010). "World Bank Haiti Situation Room – featuring OSM".

- European Commission Joint Research Centre (15 January 2010). "Haiti Earthquakes: Infrastructure Port-au-Prince 15/01/2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2012.

- "OSM Marks the SpotHaitians use a crowdsourced map to chart their own country, and its development". medium.com. 26 June 2013.

- "OSM 2012 Mali Crisis wiki page". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- MacKenzie, Debora (12 November 2013). "Social media helps aid efforts after typhoon Haiyan". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Meyer, Robinson (12 November 2013). "How Online Mapmakers Are Helping the Red Cross Save Lives in the Philippines". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Nuviun. "How the Internet is Stopping the Ebola Outbreak, One Street Map at a Time". Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "Preventative Mapping in Uganda with the Red Cross". Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Vyncke, Jorieke. "A week in Lubumbashi (DRC)". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- "Out and about in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: An OSM workshop sponsored by the World Bank". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Ibisch, Pierre & Hoffmann, Monika & Kreft, Stefan & Pe'er, Guy & Kati, Vassiliki & Biber-Freudenberger, Lisa & Dellasala, Dominick & Vale, Mariana & Hobson, Peter & Selva, Nuria. (2016). A global map of roadless areas and their conservation status. Science. 354. 1423–1427. 10.1126/science.aaf7166.Open access at researchgate.net

- "State Of The Map 2007". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2008". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2009". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2010". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2011". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2012". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2013". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "State Of The Map 2014". OpenStreetMap. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- "OpenStreetMap events in 2015". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

The SotM working group, with the support of the OSMF board, has therefore agreed that there will be no OSM Foundation organised conference this year.

- "State Of The Map 2016". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- "State Of The Map 2017". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- "State Of The Map 2018". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "State Of The Map 2020". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "State Of The Map – OpenStreetMap Wiki". wiki.openstreetmap.org. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Fairhurst, Richard (7 January 2008). "The licence: where we are, where we're going". OpenGeoData. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "Licence – OpenStreetMap Foundation". wiki.osmfoundation.org. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- Poole, Simon. "OSM V1 Objects ODbL acceptance statistics". Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Wood, Harry. "Automated redactions complete". Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- "Legal FAQ". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

Several contributors additionally make their code available under different licences

- Mata, Raj (13 June 2011). "Yahoo! Maps APIs Service Closure Announcement – New Maps Offerings Coming Soon!". Yahoo! Developer Network. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Coast, Steve (30 November 2010). "Microsoft Imagery details". OpenGeoData. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- "Community licence". NearMap. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "Microsoft releases more than 100 million Building Footprints in the US as open data". Geospatial World. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- "Microsoft Releases 125 million Building Footprints in the US as Open Data". blogs.bing.com. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- WGS 84 OpenStreetMap Wiki

- Mocnik, Franz-Benjamin; Zipf, Alexander; Raifer, Martin (18 September 2017). "The OpenStreetMap folksonomy and its evolution". Geo-spatial Information Science. 20 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1080/10095020.2017.1368193.

- "OpenStreetMap Wiki: Database". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "Databases and data access APIs". Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Cooper, Daniel (28 August 2012). "Craigslist quietly switching to OpenStreetMap data". Engadget. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- "World of the Living Dead Resurrection Expands Closed Beta". StrategyInformer.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Sometimes you have to kill something to bring it back to life". World of the Living Dead Developer Blog. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Mapping the zombocalypse: from Google to Open Street Maps". World of the Living Dead Developer Blog. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "Around the world and back again". blog-flickr.net. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- "More cities". blog-flickr.net. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- Waters, Tim (16 September 2008). "Japanese progress in osm. Amazing stuff!". thinkwhere. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Ingraham, Nathan. "Flickr is Now Using Nokia Maps". The Verge. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- "Foursquare Blog". Blog.foursquare.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- S, Maria (8 October 2013). "Smarter Fleet Management with Geotab's Posted Road Speed Information". Geotab. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Raphael, JR (8 September 2009). "'Monopoly City Streets' Online Game: Will Buying Park Place Be Any Easier?". PC World. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "Monopoly game launches on Google". BBC Online. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "MapQuest".

- "Moovit online trip planner". Moovit.com. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "Pokemon Go now uses OSM". comicbook.com.

- Groux, Christopher (1 December 2017). "'Pokémon Go' Map Updated To OSM From Google Maps: What Is OpenStreetMap?". International Business Times. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- "OpenStreetMap Nominatim: Search". Nominatim. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Nominatim". OpenStreetMap Wiki. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "OpenGeofiction". OpenGeofiction. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "OGF:About OpenGeofiction - OpenGeofiction Encyclopedia". Wiki.opengeofiction.net. 16 November 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "OGF:Territories - OpenGeofiction Encyclopedia". Wiki.opengeofiction.net. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "OGF:Admin regions - OpenGeofiction Encyclopedia". Wiki.opengeofiction.net. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "OGF:Verisimilitude - OpenGeofiction Encyclopedia". Wiki.opengeofiction.net. 10 March 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "OGF:Overwikification - OpenGeofiction Encyclopedia". Wiki.opengeofiction.net. 10 March 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Users' diaries". OpenGeofiction. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Editor, Geo (22 June 2017). "Snapchat's new Snap Map shows users their friends' locations". Retrieved 28 February 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Anderson, Elle (28 July 2015). "Feedback for Strava's new maps (OpenStreetMap)". Strava.com. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- "OpenStreetMaps and Smart Summon". Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Webots OpenStreetMap Importer". cyberbotics.com.

- "WIWOSM". Retrieved 25 July 2014.

Further reading

- Bennett, Jonathan (2010). OpenStreetMap: Be Your Own Cartographer. Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84719-750-4.

- Ramm, Frederik; Topf, Jochen; Chilton, Steve (2010). OpenStreetMap: Using and Enhancing the Free Map of the World. UIT Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-906860-11-0.