Basilicata

Basilicata (UK: /bəˌsɪlɪˈkɑːtə/,[4] US: /-ˌzɪl-/,[5] Italian: [baziliˈkaːta]), also known by its ancient name Lucania (/luːˈkeɪniə/, also US: /luːˈkɑːnjə/,[6][7] Italian: [luˈkaːnja]), is an administrative region in Southern Italy, bordering on Campania to the west, Apulia (Puglia) to the north and east, and Calabria to the south. It has two coastlines: a 30-km stretch on the Tyrrhenian Sea between Campania and Calabria, and a longer coastline along the Gulf of Taranto between Calabria and Apulia. The region can be thought of as the "instep" of Italy, with Calabria functioning as the "toe" and Apulia the "heel".

Basilicata Lucania | |

|---|---|

Region of Italy | |

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Country | Italy |

| Capital | Potenza |

| Government | |

| • President | Vito Bardi (FI) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,995 km2 (3,859 sq mi) |

| Population (3 October 2012) | |

| • Total | 575,902 |

| • Density | 58/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | English: Lucanian Italian: Lucano (man) Italian: Lucana (woman) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IT-77 |

| GDP (nominal) | €12.0 billion (2017)[1] |

| GDP per capita | €21,100 (2017)[2] |

| HDI (2017) | 0.851[3] very high · 17th of 21 |

| NUTS Region | ITF |

| Website | www.regione.basilicata.it |

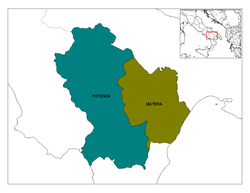

The region covers about 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi). In 2010 the population was slightly under 600,000. The regional capital is Potenza. The region is divided into two provinces: Potenza and Matera.[8][9]

Basilicata is an emerging tourist destination, thanks in particular to the city of Matera, whose historical quarter I Sassi was designated in 1993 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[10] In 2019 it was designated as the European Capital of Culture for that year. The New York Times ranked Basilicata third in its list of "52 Places to Go in 2018", describing it as "Italy’s best-kept secret".[11]

Etymology

The name probably derives from "basilikos" (Greek: βασιλικός), which refers to the basileus, the Byzantine emperor, who ruled the region for 200 years, from 536/552 to 571/590 and from 879 to 1059. Others argue that the name may refer to the Basilica of Acerenza, which held judicial power in the Middle Ages.

During the Greek and Roman Ages, Basilicata was known as Lucania. This was possibly derived from "leukos" (Greek: λευκός), meaning "white", from "lykos" (Greek: λύκος), meaning "wolf", or from Latin word "lucus", meaning "sacred wood".

Geography

Basilicata covers an extensive part of the southern Apennine Mountains, between the Ofanto river in the north and the Pollino massif in the south. It is bordered on the east by a large part of the Bradano river depression, which is traversed by numerous streams and declines to the southeastern coastal plains on the Ionian Sea. The region also has a short coastline to the southwest on the Tyrrhenian Sea side of the peninsula.

Basilicata is the most mountainous region in the south of Italy, with 47% of its area of 9,992 km2 (3,858 sq mi) covered by mountains. Of the remaining area, 45% is hilly, and 8% is made up of plains. Notable mountains and ranges include the Pollino massif, the Dolomiti lucane, Monte Vulture, Monte Alpi, Monte Carmine, Monti Li Foj and Toppa Pizzuta.

Geological features of the region include the volcanic formations of Monte Vulture, and the seismic faults in the Melfi and Potenza areas in the north, and around Pollino in the south. Much of the region was devastated in the 1857 Basilicata earthquake. More recently, the 1980 Irpinia earthquake destroyed many towns in the northwest of the region.

The mountainous terrain combined with weak rock and soil types makes landslides prevalent. The lithological structure of the substratum and its chaotic tectonic deformation predispose the slope to landslides, and this problem is compounded by the lack of forested land. In common with many another Mediterranean region, Basilicata was once rich in forests, but they were largely felled and made barren during the time of Roman rule.

The variable climate is influenced by three coastlines (Adriatic, Ionian and Tyrrhenian) and the complexity of the region's physical features. In general, the climate is continental in the mountains and Mediterranean along the coasts.

History

Prehistory

The first traces of human presence in Basilicata date to the late Paleolithic, with findings of Homo erectus. Late Cenozoic fossils, found at Venosa and other locations, include elephants, rhinoceros and species now extinct such as a saber-toothed cat of the genus Machairodus. Examples of rock art from the Mesolithic have been discovered near Filiano. From the fifth millennium, people stopped living in caves and built settlements of huts up to the rivers leading to the interior (Tolve, Tricarico, Aliano, Melfi, Metaponto). In this period, anatomically modern humans lived by cultivating cereals and animal husbandry (Bovinae and Caprinae). Chalcolithic sites include the grottoes of Latronico and the funerary findings of the Cervaro grotto near Lagonegro.

The first known stable market center of the Apennine culture on the sea, consisting of huts on the promontory of Capo la Timpa, near to Maratea, dates to the Bronze Age.

The first indigenous Iron Age communities lived in large villages in plateaus located at the borders of the plains and the rivers, in places fitting their breeding and agricultural activities. Such settlements include that of Anglona, located between the fertile valleys of Agri and Sinni, of Siris and, on the coast of the Ionian Sea, of Incoronata-San Teodoro. The first presence of Greek colonists, coming from the Greek islands and Anatolia, date from the late eighth century BC.

There are virtually no traces of survival of the 11th–8th century BC archaeological sites of the settlements (aside from a necropolis at Castelluccio on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea): this was perhaps caused by the increasing presence of Greek colonies, which changed the balance of the trades.

Ancient history

In ancient historical times the region was originally known as Lucania, named for the Lucani, an Oscan-speaking population from central Italy. Their name might be derived from Greek leukos meaning "white", lykos ("gray wolf"), or Latin lucus ("sacred grove"). Or more probably Lucania, as much as the Lucius forename (praenomen) derives from the Latin word Lux (gen. lucis), meaning "light" (<PIE *leuk- "brightness", Latin verb lucere "to shine"), and is a cognate of name Lucas. Another etymology proposed is a derivation from Etruscan Lauchum (or Lauchme) meaning "king", which however was transferred into Latin as Lucumo.[12]

Starting from the late eighth century BC, the Greeks established a settlement first at Siris, founded by fugitives from Colophon. Then with the foundation of Metaponto from Achaean colonists, they started the conquest of the whole Ionian coast. There were also indigenous Oenotrian foundations on the coast, which exploited the nearby presence of Greek settlements, such as Velia and Pyxous, for their maritime trades.

The first contacts between the Lucanians and the Romans date from the latter half of the fourth century BC. After the conquest of Taranto in 272, Roman rule was extended to the whole region: the Appian Way reached Brindisi and the colonies of Potentia (modern Potenza) and Grumentum were founded.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Basilicata fell to Germanic rule, which ended in the mid-6th century when the Byzantines reconquered it from the Ostrogoths between 536 and 552 during the apocalyptic Byzantine-Gothic war under the leadership of Byzantine generals Belisarius and Narses. The region, deeply Christianized since as early as the 5th century, became part of the Lombard Duchy of Benevento founded by the invading Lombards between 571 and 590. In the following centuries, Saracen raids led part of the population to move from the plain and coastal settlements to more protected centers located on hills. The towns of Tricarico and Tursi were under Muslim rule for a short period: later the "Saracen" population would be expelled.[13] The region was conquered once more for Byzantium from the Saracens and the Lombards in the late 9th century, with the campaigns of Nikephoros Phokas the Elder and his successors, and became part of the theme of Longobardia. In 968 the theme of Lucania was established, with the capital at Tursikon (Tursi). In 1059, Basilicata, together with the rest of much of southern Italy, was conquered by the Italo-Normans. Later, it was inherited by the Hohenstaufen, who were ousted in the 13th century by the Capetian House of Anjou.

Modern and contemporary ages

In 1485, Basilicata was the seat of plotters against King Ferdinand I of Naples, the so-called "Conspiracy of the Barons", which included the Sanseverino of Tricarico, the Caracciolo of Melfi, the Gesualdo of Caggiano, the Orsini Del Balzo of Altamura and Venosa and other anti-Aragonese families. Later, Charles V stripped most of the barons of their lands, replacing them with the Carafa, Revertera, Pignatelli and Colonna among others. After the formation of the Neapolitan Republic (1647), Basilicata also rebelled, but the revolt was suppressed. In 1663 a new province was created in Basilicata with its capital in Matera.

The region became part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1735. Basilicata autonomously declared its annexation to the Kingdom of Italy on August 18, 1860 with the Potenza insurrection. It was during this period that the State confiscated and sold off vast tracts of Basilicata's territory formerly owned by the Catholic Church. As the new owners were a handful of wealthy aristocratic families, the average citizen did not see any immediate economic and social improvements after unification, and poverty continued unabated. This gave rise to the phenomenon of Brigandage in Southern Italy after 1861, whereby the Church encouraged the local people to rise up against the nobility and the new Italian state. This strong opposition movement continued for many years. Carmine Crocco from Rionero in Vulture was the most important chief in the region and the most impressive leader in southern Italy.[14]

It was only really after World War II that things slowly began to improve thanks to land reform. In 1952, the inhabitants of the Sassi di Matera were rehoused by the State, but many of Basilicata's population had emigrated or were in the process of emigrating, which led to a demographic crisis from which it is still recovering.

In 1993, UNESCO declared the Sassi di Matera a World Heritage Site. Meanwhile, Fiat Automobiles established a huge factory in Melfi, leading to jobs and an upsurge in the economy. In the same year the Pollino National Park was established.

Economy

Cultivation consists mainly of sowables (especially wheat), which represent 46% of the total land. Potatoes and maize are produced in the mountain areas. Olives and vine production is relatively small with about 31,000 hectares (77,000 acres) under cultivation.[15] The terrain is mountainous and hilly with poor transportation routes that hinders harvesting. Most oils are sold unbranded and only 3% is exported. The main olive cultivars are Ogliarola del Vulture, Ogliarola del Bradano, Majatica di Ferrandina and Farasana with only Ogliarola del Vulture having the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).[16] Other varieties are the Arnasca, Ascolana, Augellina, Cellina, Frantoio, Leccino, Majatica, Nostrale, Ogliarola (Ogliarola Barese), Palmarola or Fasolina, Rapolese di Lavello, and Sargano (Sargano di Fermo and Sargano di San Benedetto).[17]

A quality wine called "Aglianico del Vulture" is produced around Rionero and received the d.o.c. classification in 1971. There are several wines such as Vino Spumante Rosso d.o.c., Aglianico di Matera from Matera produced from a mixture of the Montepulciano and other grapes, Lambrusco del Basento made from Lambrusco Maestri grapes, and Malvasia del Vulture from Malvasia grapes.[18] According to the latest Census of Agriculture, there are large herds of cattle (77,711 head in 2000).[19]

Among industrial activities, the manufacturing sector contributes to the gross value added of the secondary sector with 64% of the total, while the building sector contributes 24%. Within the services sector, the main activities in terms of gross value added are business activities, distributive trade, education and public administration. In the last few years, new productive sectors have developed: manufacturing, automotive, and especially oil extraction. In 2009, Eni employed 230 people in this area (of whom over 50% were from Basilicata), and about 1,800 were employed in activities directly generated by Eni's operations, distributed in 80 companies of which over 50% were from Basilicata.[20] The region produced about 100,000 bbl/d (16,000 m3/d), meeting 11 percent of Italy's domestic oil demand.[21]

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 12.6 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 0.7% of Italy's economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 22,200 euros or 74% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 95% of the EU average.[22]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 509,000 | — |

| 1871 | 524,000 | +2.9% |

| 1881 | 539,000 | +2.9% |

| 1901 | 492,000 | −8.7% |

| 1911 | 486,000 | −1.2% |

| 1921 | 492,000 | +1.2% |

| 1931 | 514,000 | +4.5% |

| 1936 | 543,000 | +5.6% |

| 1951 | 628,000 | +15.7% |

| 1961 | 644,000 | +2.5% |

| 1971 | 603,000 | −6.4% |

| 1981 | 610,000 | +1.2% |

| 1991 | 611,000 | +0.2% |

| 2001 | 598,000 | −2.1% |

| 2010 (estimate) | 587,000 | −1.8% |

| 2017 | 570,365 | −2.8% |

| Source: ISTAT, 2001 | ||

Although Basilicata has never had a large population, there have nevertheless been quite considerable fluctuations in the demographic pattern of the region. In 1881, there were 539,258 inhabitants but by 1911 the population had decreased by 11% to 485,911, mainly as a result of emigration overseas. There was a slow increase in the population until World War II, after which there was a resurgence of emigration to other countries in Europe, which continued until 1971 and the start of another period of steady increase until 1993 (611,000 inhabitants). However, in recent years the population has decreased as a result of a new wave of migration, both towards northern Italy and to other countries in Europe, and a reduction in the birth rate.[23]

The population density is very low compared to that of Italy as a whole: 59.1 inhabitants per km² compared to 200.4 nationwide in 2010. There is not a great difference between the population densities of the provinces of Matera and Potenza.[23]

Government and politics

Administrative divisions

Basilicata is divided into two provinces:

| Province | Area (km2) | Population | Density (inh./km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Matera | 3,447 | 203,837 | 59.1 |

| Province of Potenza | 6,545 | 387,107 | 59.1 |

Notable people

Notable people linked to Basilicata include:

- Pythagoras (c. 570–495 BC): Greek philosopher

- Ocellus Lucanus (fl. 5th century BC): Greek philosopher

- Hippasus of Metapontum (fl. 5th century BC): Greek philosopher

- Zeuxis (fl. 5th century BC): painter

- Marcus Claudius Marcellus (c. 268–208 BC), Roman consul and general

- Horace (65 BC–8 BC): Roman poet

- Ilario of Matera (c. 980–1045): Christian monk and saint

- Robert Guiscard (c. 1015–1085): Norman mercenary

- Gerard of Potenza (d. 1119): bishop and saint

- Obadiah the Proselyte (fl. 12th century): Byzantine Jew composer

- Frederick II (1194–1250): Holy Roman Emperor

- Manfred (1232–1266): King of Sicily

- Roger of Lauria (c. 1245–1305): admiral

- Joanna I (1328–1382): Queen of Naples

- Altobello Persio (1507–1593): sculptor

- Isabella di Morra (c. 1520–1545/1546): poet

- Carlo Gesualdo (1566–1613): composer and murderer

- Tommaso Stigliani (1573–1651): writer and poet

- Egidio Romualdo Duni (1708–1775): composer

- Gerard Majella (1726–1755), friar and Catholic Saint

- Francesco Mario Pagano (1748–1799): jurist and philosopher

- Joseph Forlenze (1757–1833): Italian French surgeon

- Giustino de Jacobis (1800–1860): bishop and Catholic saint

- Ferdinando Petruccelli della Gattina (1815–1890): journalist and patriot

- Giambattista Pentasuglia (1821–1880): patriot and politician

- Carmine Crocco (1830–1905): brigand

- Michele Torraca (1840–1906): journalist and politician

- Domenico Ridola (1841–1932): physician, politician and archaeologist

- Giuseppe Gattini (1843–1917): politician and historian

- Giovanni Passannante (1849–1910): anarchist

- Emanuele Gianturco (1857–1907): jurist and politician, Minister of Education and Minister of Justice of the Kingdom of Italy

- Francesco Saverio Nitti (1868–1953): economist and politician, Prime Minister of Italy

- Leonardo De Lorenzo (1875–1962): flautist and music educator

- Joseph Stella (1877–1946): Italian American painter

- Robert G. Vignola (1882–1953): Italian American actor and film director

- Johnny Torrio (1882–1957): Italian American mobster

- Carlo Alianello (1901–1981): writer and screenplay writer

- Carlo Levi (1902–1975): writer, painter and anti-fascist

- Young Corbett III (1905–1993): Italian American boxer

- Leonardo Sinisgalli (1908–1981): poet and art critic

- Anthony J. Celebrezze (1910–1998): Italian American politician

- Albino Pierro (1916–1995): poet, was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature

- Emilio Colombo (1920–2013): politician, Prime Minister of Italy and President of the European Parliament

- Rocco Scotellaro (1923–1953): poet, writer and politician

- Donato_Scutari (1925–2012) politician, anti-fascist

- Rocco Petrone (1926–2006): Italian American engineer, director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center, and director of the Apollo program.

- Lina Wertmüller (1928): film director and screenwriter

- Vittorio Camardese (1929–2010): guitarist and physicians

- Anne Bancroft (1931–2005): American actress

- Ron Galella (1931): American photographer, known as a paparazzo

- Cosimo Damiano Fonseca (1932): religious and historian, first rector of the University of Basilicata

- Mariele Ventre (1939–1995): musician and singer, the founder and director of Italian children's choir Piccolo Coro dell'Antoniano

- Antonio Mario Tamburro (1939–2009): chemist, rector of the University of Basilicata

- Francis Ford Coppola (1939): American film director and screenwriter

- Ruggero Deodato (1939): film director and screenwriter

- Danny DeVito (1944): American actor

- Samuel Alito (b. April 1, 1950) Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Mother from San Chirico Nuovo, Potenza

- Wally Buono (b. 1950 AD): Canadian Football Head Coach and retired player

- Mango (1954–2014): singer-songwriter

- Rocco Papaleo (1958): actor, film director and singer

- Gianni Pittella (1958): politician and President of the European Parliament

- Bill de Blasio (1961): American politician, Mayor of New York City

- Gerardo Martino (1962): Argentine football manager

- Michele Miglionico (1965): Italian fashion designer

- Billie Joe Armstrong (1972): American musician, leader of the rock band Green Day

- Fabian Cancellara (1981): Swiss professional road bicycle racer

- Domenico Pozzovivo (1982): professional road bicycle racer

- Arisa (1982): singer and actress

- Rocco Sabato (1982): professional footballer

- Simone Zaza (1991): professional footballer

References

- "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 31% to 626% of the EU average in 2017" (Press release). ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- "Basilicata". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Basilicata". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Basilicata". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Lucania". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Basilicata nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it.

- "lucano in Vocabolario – Treccani". www.treccani.it.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Sassi and the Park of the Rupestrian Churches of Matera". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "52 Places to Go in 2018". The New York Times. 2018-01-10. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Bonfante G., Bonfante L, The Etruscan Language: An Introduction, 1983, p. 59.

- Archivio storico per le province napoletane. Società napoletana di storia patria. 1876.

- Eric Hobsbawm, Bandits, Penguin, 1985, p. 25.

- FAO.org: Olive production: Olive Production: Extension, Consumption, and Exportation (pp.14)- Retrieved 2018-07-03

- Olive oil Times: Basilicata- Retrieved 2018-07-03

- Italian olives- Retrieved 2018=07-03

- Wines of Basilicata- Retrieved 2018-07-03

- "Eurostat". Circa.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Archived 11 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Oil Exploration in Basilicata, Italy". Fossilfreeeib.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- "Eurostat". Circa.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Basilicata. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basilicata. |