Ligures

The Ligures (singular Ligus or Ligur; English: Ligurians; Greek: Λίγυες) were an ancient population that gave the name to Liguria, a region of north-western Italy.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

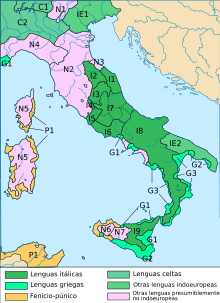

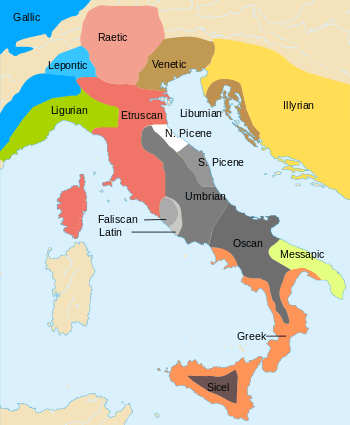

In pre-Roman times, the Ligurians occupied present-day Italian regions of Liguria, Piedmont south of the Po river and north-western Tuscany, and the French region of PACA. However, it is generally believed that around 2000 BC, the Ligurians occupied a much larger area, including much of north-western Italy up to all of northern Tuscany north of the Arno river, southern France and presumably part of modern Catalonia, in the north-east of Iberian Peninsula.[2][3][4]

Little is known of the Old Ligurian language, the lack of inscriptions does not allow a certain linguistic classification: Pre-Indo-European[5] or an Indo-European language of the Celtic language family.[6] The problem is closely related to the lack of inscriptions, and to the equally mysterious origin of the ancient Ligurian people. The linguistic hypotheses are mainly based on toponyms and names of persons.

Because of the strong Celtic influences on their language and culture, they were known in antiquity as Celto-Ligurians (in Greek Κελτολίγυες Keltolígues).[7] and it is generally believed, after a certain point, that Old Ligurian became an Indo-European language with particularly strong Celtic affinities, as well as similarities to Italic languages. Only some proper names have survived, such as the inflectional suffix -asca or -asco "village".[8]

Name

The name Liguria and Ligures predates Latin and is of obscure origin, however the Latin adjectives Ligusticum (as in Mare Ligusticum) and Liguscus[9] reveal the original -sc- in the root ligusc-, which shortened to -s- and turned into -r- in the Latin name Liguria according to rhotacism. The formant -sc- (-sk-) is present in the names Etruscan, Basque, Gascony and is believed by some researchers to relate to maritime people or sailors.[10][11]

Compare Ancient Greek: λίγυς, romanized: Lígus, lit. 'a Ligurian, a person from Liguria' whence Ligustikḗ λιγυστική transl. the name of the place Liguria.[12]

The term Ligurian seems to be related to Loire river. The name of the French river in fact derives from the Latin "Liger", the latter probably from the Gallic *liga, meaning mud or silt.[13] Liga derives from the root proto-Indo-European *legʰ-, meaning "lie", as in the Welsh word Lleyg.[14]

According to Plutarch, the Ligurians called themselves Ambrones, which could indicate a relationship with the Ambrones of northern Europe.[15] Plutarch however refers to a single episode (the battle of Aquae Sextiae of 102 BC), when the Ligurian auxiliares of the Romans against the Cimbrians and the Teutons screamed "Ambrones!" as a battle cry, obtaining in response the same battle cry from the opposing front; but on the episode there are opposite interpretations.

It is not known how the Ligurians called themselves in their language and if they had a term to define themselves. "Ligurians" is a term that derives from the name by which the Greeks called this ethnic group (Ligues) when they began exploring the western Mediterranean. Later, in late times, they too began to use this term to differentiate themselves from other ethnic groups.

One opinion, it is that originally the Ligurians did not have a term to define their entire ethnicity, but only had names by which they defined themselves as members of a particular tribe. Only when they had to deal with united and organized peoples (Greeks, Etruscans, Romans) and had to federate to defend themselves would they have felt the need to recognize themselves ethnically through a single term.

Controversy and geographical area of ancient Liguria

The geography of Strabo, from book 2, chapter 5, section 28 :

The Alps are inhabited by numerous nations, but all Keltic with the exception of the Ligurians, and these, though of a different race, closely resemble them in their manner of life. They inhabit that portion of the Alps which is next the Apennines, and also a part of the Apennines themselves. This latter mountain ridge traverses the whole length of Italy from north to south, and terminates at the Strait of Sicily.[16].

This zone corresponds to the current region of Liguria in Italy as well as to the former county of Nice which could be compared today to the Alpes Maritimes.

History

Proto-history of northern Italy

The Polada Culture (a location near Brescia, Lombardy, Italy) was a cultural horizon extended in the Po valley from eastern Lombardy and Veneto to Emilia and Romagna, formed in the first half of 2nd millennium BC perhaps for the arrival of new people from the transalpine regions of Switzerland and Southern Germany.[17] Its influences are also found in the cultures of the Early Bronze Age of Liguria, Corsica, Sardinia (Bonnanaro culture) and southern France. There are some commonalities with the previous Bell Beaker Culture including the usage of the bow and a certain mastery in metallurgy.[18] Apart from that, the Polada culture does not correspond to the Beaker culture nor to the previous Remedello culture.

The Bronze tools and weapons show similarities with those of the Unetice Culture and other groups in north of Alps. According to Bernard Sergent, the origins of the Ligurian language, in his opinion related to the distant with Celtic and Italic languages families, would be sought in the Polada Culture and that of the Rhone (early Bronze Age), southern emanations of the Unetice Culture.

It is said that the ligurians inhabited the Po valley around the 2,000 B.C., they not only appear in the legends of the Po valley, but would have left traces (linguistic and craft) found in the archaeological also in the area near the northern Adriatic coast.[19] The Ligurians are credited with forming the first villages in the Po Valley of the facies of the pile dwellings and of the dammed settlements[20], a society that followed the Polada culture, and is well suited in middle and late Bronze Age.

The ancient name of Po river (Padus in Latin) derived from the Ligurian name of the river: [21] Bod-encus or Bod-incus. This word appears in the place name Bodincomagus, a Ligurian town on the right bank of the Po downstream near today's Turin.[22]

According to a legend, of the late Bronze Age are the foundations of Brescia and Barra (Bergamo) by Cydno, the forefather of Ligurians.[23]This myth seems to have a grain of truth, because recent archaeological excavations have unearthed remains of a settlement dating back to 1,200 B.C. that scholars presume to have been built and inhabited by Ligures peoples.[24][25] Others scholars attribute the founding of Bergamo and Brescia to the Etruscans.[26][27]

With the facies of the pile dwellings and of the dammed settlements, the continuity of the previous Polada culture of the ancient Bronze Age seems to be unbroken. The villages, as in the previous phase, are on stilts and are concentrated in the area of the Lake of Garda. In the plains appear instead villages with levees and ditches.

The settlements were usually made up of stilt houses; the economy was characterized by agricultural and pastoral activities, hunting and fishing were also practiced as well as the metallurgy of copper and bronze (axes, daggers, pins etc.). Pottery was coarse and blackish.[28]

The bronze metallurgy (weapons, work tools, etc.) was well developed among these populations. As for the burial customs both cremation and inhumation were praticted

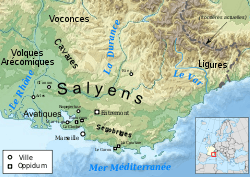

The foundation of Massalia

Between the 10th and 4th century BC, the Ligures were found in Provence from Massilia. According to Strabo, the Ligurians, living in proximity of numerous Celtic mountain tribes, were a different people (ἑτεροεθνεῖς), but "were similar to the Celts in their ways of life".[29]

Massalia, whose name was probably adapted from an existing Ligurian name,[30] was the first Greek settlement in France.[31] It was established within modern Marseille around 600 BC by colonists coming from Phocaea (now Foça, in modern Turkey) on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor. The connection between Massalia and the Phoceans is mentioned in Thucydides's Peloponnesian War;[32] he notes that the Phocaean project was opposed by the Carthaginians, whose fleet was defeated.[33]

The founding of Massalia has also been recorded as a legend. According to the legend, Protis, or Euxenes, a native of Phocae, while exploring for a new trading outpost or emporion to make his fortune, discovered the Mediterranean cove of the Lacydon, fed by a freshwater stream and protected by two rocky promontories.[34] Protis was invited inland to a banquet held by Nannu, the chief of the local ligurian tribe of Segobrigi, for suitors seeking the hand of his daughter Gyptis in marriage. At the end of the banquet, Gyptis presented the ceremonial cup of wine to Protis, indicating her unequivocal choice. Following their marriage, they moved to the hill just to the north of the Lacydon; and from this settlement grew Massalia.[35] Robb gives greater weight to the Gyptis story, though he notes that the tradition was to offer water, not wine, to signal the choice of a marriage partner.[36] Later, the natives would treacherously lay a plot to destroy the new colony, but the scheme was divulged and Conran, king of the natives, was killed in the ensuing battle.[37] Probably the Greeks expressed the intention to expand the territory of the colony, and this is why Conran ( the son of Nannu),tried to destroy it. However, the resistance of the Ligurians had the effect of reducing the Greek claims, which renounced territorial expansion. The massaliotes ended up concentrating on the development of trade, first with the Ligurians, and then with the Gauls, until Massalia became the most important port in Gaul.

The arrival and the fusion with the Celts

Between the 8th and 5th centuries BC, tribes of Celtic peoples, probably coming from Central Europe, also began moving into Provence. They had weapons made of iron, which allowed them to easily defeat the local tribes, who were still armed with bronze weapons.

Ligurians and newly-arrived Celts spread throughout the area, sharing the territory of modern Provence, Celts and Ligurians later started to inter-mixing between each other and form a Celto-Ligurian culture, with many tribes. Each tribe in its own alpine valley or settlement along a river, each with its own king and dynasty. Of these numerous Celto-Ligurian tribes, the Salluvi settled north of Massalia, in the area of Aix-en-Provence while Caturiges, Tricastins, and Cavares settled to the west of the Durance river.[38] They built hilltop forts and settlements, later given the Latin name oppida. Today the traces 165 oppida are found in the Var, and as many as 285 in the Alpes-Maritimes.[39]

They worshipped various aspects of nature, establishing sacred woods at Sainte-Baume and Gemenos, and healing springs at Glanum and Vernègues. Later, in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, the different tribes formed confederations; the Voconces in the area from the Isère to the Vaucluse; the Cavares in the Comtat; and the Salyens, from the Rhône river to the Var. The tribes began to trade their local products, iron, silver, alabaster, marble, gold, resin, wax, honey and cheese; with their neighbours, first by trading routes along the Rhône river, and later Etruscan traders visited the coast. Etruscan amphorae from the 7th and 6th centuries BC have been found in Marseille, Cassis, and in hilltop oppida in the region.[40]

The Corsi

Corsi were an ancient people of Sardinia and Corsica, to which they gave the name. They dwelt at the extreme north-east of Sardinia, in the region today known as Gallura, [41]

According to historian Ettore Pais and archeologist Giovanni Ugas, the Corsi probably belonged to the Ligurian people.[42][43] Similar was also the opinion of Seneca, who claimed that the Corsi from Corsica, where he had then been staying in exile, were of mixed origin, resulting from the continuous mingling of various ethnic groups of foreign origin, like the Ligures, the Greeks and the Iberians.[44] In a myth, reported by Sallust, the peopling of Corsica is traced back to Corsa, a Ligurian woman who when grazing her cattle, went to the island, which then took her name.

The Massaliotes in 565 or 562 B.C. founded the colony of Alalia, at the site of the current city of Aleria. The Greeks called the island first Kalliste and then Cyrnos, Cernealis, Corsis and Cirné.

In 535 B.C., following the Battle Alalia, they were defeated by an Etruscan-Carthaginian coalition formed on a pact specifically stipulated and that, after the conflict, in case of victory, provided for the division of the two islands on which the influence had been conquered: Sardinia to the Carthaginians, Corsica to the Etruscans. In reality, according to Herodotus, the Focei had won, but it would have been a pyrrhic victory, given that of the 60 ships employed (half of the total armoury of the opposing fleets) 40 were sunk and the remaining rendered useless. The Massaliotes then left Corsica and the Carthaginians and Etruscans were able to give substance equally to the pact of partition. The Etruscans regained control over the eastern shores of the island, which they had already consolidated with the activity of the war marinas of Pisa, Volterra, Populonia, Tarquinia and Cere.

Between Celts and Etruscans

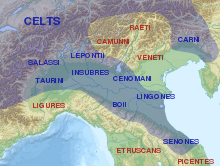

The Celto-Ligurian fusion in Western Alps and Po Valley

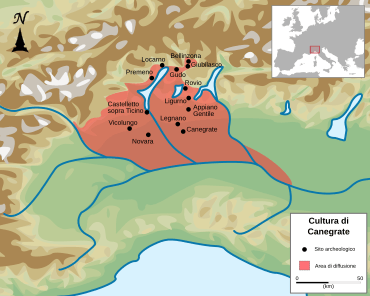

Starting from the 12th century B.C., from the union of the previous cultures of Polada and Canegrate, that is from the union of pre-existing Ligurian populations with the arrival of Celtic populations, at the same time as the birth of the Hallstatt culture in central Europe and the Villanova culture in central Italy, a new civilization developed that archaeologists call Golasecca from the name of the place where the first discoveries were found.

The People of Golasecca Culture inhabited a territory of about 20,000 km², from the Alpine watershed to the Po, from Valsesia to the Serio, gravitating around three main centers: the area of Sesto Calende, Bellinzona, but especially the protourban center of Como.

With the arrival of Gallic populations from beyond the Alps, in the 4th century B.C. this Celtic-Ligurian civilization declined and came to an end.

The Etruscan expansion in the plain of the Po and the invasion of the Gauls confined the Ligurians between the Alps and the Apennines, where they offered such resistance to Roman penetration that they gained a reputation with the ancients for primitive fierceness.

The Cultures of Canagrate, Polada and Golasecca

The Canegrate culture (13th century BC) may represent the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic[45] population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore and Lake Como (Scamozzina culture). They brought a new funerary practice—cremation—which supplanted inhumation. It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (16th-15th century BC), when North Western Italy appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artifacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture (Central Europe, 1600 BC - 1200 BC).[46] The bearers of the Canegrate culture maintained its homogeneity for only a century, after which it melded with the Ligurian aboriginal populations and with this union gave rise to a new phase called the Golasecca culture,[47][48] which is nowadays identified with the Lepontii[49][50]and other Celto-Ligurian tribes[51]

Within the Golasecca culture territory, which has become Cisalpine Gaul, now included in areas belonging to two Italian regions (West Lombardy and eastern Piedmont) and Ticino in Switzerland, it could observe that some areas that have a greater concentration of findings and that correspond broadly to the different archaeological facies attested in the Culture of Golasecca. They coincide, in a significant way, with the territories occupied by those tribal groups whose names are reported by Latin and Greek historians and geographers[46]:

- Insubri: in the area south of Lake Maggiore, in Varese and part of Novara with Golasecca, Sesto Calende, Castelletto sopra Ticino; from the fifth century BC this area remains suddenly depopulated, while the first settlement of Mediolanum (Milan) rises.

- Leponti: in the Canton of Ticino, with Bellinzona and Sopra Ceneri; in the Ossola.

- Orobi: in the area of Como and Bergamo.

- Laevi and Marici: in Lomellina (Pavia/Ticinum).

The Celts have not imposed themselves on the existing tribes, but have mixed with them. When the Etruscans and Romans arrived, north-west Italy was inhabited by a complex network of Celtic-Ligurian populations with some geographical differences: in general, to the north of the Po (named Gallia Transpadana later by Romans ), Celtic culture prevailed decisively, while to the south (Gallia Cispadana named later) the Ligurian imprint continued to leave important traces.

Looking at North-Western Italy up to the Po river, while in modern Lombardy and eastern Piedmont the Golasecca culture emerged, in the westernmost part there are 2 principal tribal groups: the Taurini in the area of Turin and the Salassi in modern Ivrea and the Aosta Valley.

The Etruscan expansion and foundation of Genua

Ligurian sepulchres of the Italian Riviera and of Provence, holding cremations, exhibit Etruscan and Celtic influences.[52]

In the seventh century BC, in addition to the Greeks, the Etruscans also began to push in the northern Tyrrhenian Sea, until what is now call the Ligurian Sea.

Although they had intense commercial exchanges, they were competitors of the Greeks, with whom they often clashed. From 540 B.C. about the Etruscan presence in the Po Valley experienced a renewed expansion in the scenario following the Battle of Alalia resulted in a progressive limitation of Etruscan movements in the Upper Tyrrhenian Sea.[53] The expansion to the north of the Apennines is characterized by that moment as aimed at identifying and controlling new trade routes

Their expansionist policy was different from that of the Greeks: their expansion was mainly by land, trying gradually to occupy the areas bordering them. Even though they were good sailors, they did not found far away colonies, but at the very least emporiums destined to support trade with the local populations. This created an ambivalence in the relations with the Ligurians; on the one hand they were excellent commercial partners for all the coastal emporiums, on the other hand, their expansionist policy led them to press on the Ligurian populations settled north of the Arno river, making them retreat into the mountain areas of the northern Apennines.

Even in this case, the Ligurian opposition prevented the Etruscans from going further; indeed, although traditionally the border between the Ligurian and Etruscan areas is considered the Magra river, it is testified that the Etruscan settlements north of the Arno (for example Pisa) were periodically attacked and plundered by the Ligurian tribes of the mountains.

As already mentioned, hostility to the borders did not prevent an intense commercial relationship, as evidenced by the large quantity of Etruscan ceramics found in the Ligurian sites. Of this period is the foundation of the oppida of Genua (nowadays Genoa, about 500 BC), the urban core of the "Castello" (perhaps an ancient Ligurian oppidum) began[54], for flourishing trade, to expand towards today's Prè (the area of meadows) and the Rivo Torbido. Some scholars believe that Genoa was an Etruscan emporium, and that only later, the local Ligurian tribe took control (or merged with the Etruscans).[55]

From the beginning of the fifth century BC, the Etruscan power began to decline: attacked in the north by the Gauls, south by the Greeks and with the revolts of controlled cities (e.g. Rome), the Etruscan presence among the Ligurians came less and less, intensifying massilian and gallic influence

From that moment on, Genoa, inhabited by the Ligurian Genuati, was considered by the Greeks, given its strong commercial character, "the emporium of the Ligurians": wood for shipbuilding, livestock, leather, honey, textiles were some of the Ligurian products of commercial exchange.

First contacts with Romans

In the third century B.C., the Romans, having been right of the Etruscans and integrated their territories, found themselves in direct contact with the Ligurians. However, Roman expansionism was directed towards the rich territories of Gaul and the Iberian Peninsula (then under Carthaginian control), and the territory of the Ligurians was on the road (they controlled the Ligurian coasts and the South-western Alps).

At the beginning the Romans had a rather condescending attitude: the Ligurian territory was considered poor, while the fame of its warriors was known (they had already met them as mercenaries), finally they were already engaged in the First Punic War and were not willing to open new fronts, so they tried first of all to make them allies. However, despite their efforts, only a few Ligurian tribes made alliance agreements with the Romans (the alliance with the Genuates is famous), the rest immediately proved hostile.

The hostilities were opened in 238 BC by a coalition of Ligurians and Gauls Boi, but the two peoples soon found themselves in disagreement and the military campaign came to a halt with the dissolution of the alliance. Meanwhile, a Roman fleet commanded by Quintus Fabius Maximus routed Ligurian ships on the coast (234-233 BC), allowing the Romans to control the coastal route to and from Gaul.

In in 222 B.C. the Insubres, during a war with Romans occupied the oppidum of Clastidium, that at that time, it was an important locality of the Anamari (or Marici), a Ligurian tribe that, probably for fear of the nearby warlike Insubres, had already accepted the alliance with Rome the year before.

For the first time the Roman army go beyond the Po, spreading Gallia Transpadana: the battle of Clastidium, in 222 B.C., earned Rome the taking of the capital of the Insubres: Mediolanum (Milan). To consolidate its dominion, Rome created the colonies of Placentia, in the territory of the Boii, and Cremona in that of the Insubri.[56]

Second Punic War

With the outbreak of the second Punic war (218 B.C.) the Ligurian tribes had different attitudes:

- a part (the tribes of the west Riviera and the Apuani) allied with the Carthaginians, providing soldiers to Hannibal's troops when he arrived in Northern Italy (they hoped that the Carthaginian general would free them from the Roman neighbor);

- another part (Genuates, Bagienni and the Taurini) took sides in support of the Romans.

The pro-carthage Ligurians took part in the Battle of the Trebia, in which the Carthaginians won. Other Ligurians enlisted in the army of Hasdrubal Barca, when he came down to Cisalpine Gaul (207 BC), in an attempt to rejoin the troops of his brother Hannibal. In the port of Savo (the present Savona), then capital of the Ligures Sabazi, the trireme ships of the Carthaginian fleet of General Mago Barca, brother of Hannibal, destined to cut the Roman trade routes in the Tyrrhenian Sea, found shelter.

To the pro-Roman Ligurians, at the beginning it did not go as well. Taurini were on the road of Hannibal to enter in Italy and in 218 BC, they were attacked by him, who had allied with their long-standing enemies: the Insubres. The Taurini chief town (Taurasia, now Turin), was captured by Hannibal's forces after a three-day siege.[57]

In 205 BC, Genua was attacked and razed to the ground by Mago.[58]

With the reversal of the fate of the Second Punic War, Mago (203 BC) is among the Ingauni, trying to block the Roman advance: suffered a serious defeat that cost him his life, in the same year was rebuilt Genua. Ligurian troops are still present, as Hannibal's chosen troop, at the battle of Zama in 202 BC, which decreed the defeat of Carthage.[59]

Roman conquest of "Cisalpine Ligurians"

In 200 B.C. Ligurians and Boii sacked and destroyed the Roman colony of Placentia, effectively controlling the most important ford of the Po Valley.[60]

During the same period the Romans were at war with the Apuani. The serious effort began in 182, when both consular armies and a proconsular army were sent against the Ligurians. The wars continued into the 150s, when victorious generals celebrated two triumphs over the Ligurians. Here also the Romans drove many natives off their land and settled colonies in their stead (e.g., Luna and Luca in the 170s).[61]

By the end of the Second Punic War, however, hostilities were not over. Ligurian tribes, Gauls and skidding Carthaginian troops, starting from the mountain territories, continued to fight with guerrilla tactics. Thus the Romans were forced into continuous military operations in northern Italy.

In 201 BC the Ingauni were forced to surrender.

Only in 197 B.C. the Romans, under the leadership of Minucius Rufus, succeeded in regaining control of the Placentia area by subduing the Celelates, the Cerdicates, the Ilvati and the Boi Gauls and occupying the oppida of Clastidium.

Genua was rebuilt by the proconsul Spurius Lucretius and in 197 BC. Defeated Carthage, Rome aimed to expand northwards, and used Genua as a support base for raids, between 191 and 154 BC, against the Ligurian tribes of the hinterland, allied for decades with Carthage.

A second phase of the conflict followed (197-155 B.C.), characterized by the fact that the Apuani Ligurians entrenched themselves on the Apennines, from where they periodically descended to plunder the surrounding territories. The Romans, for their part, organized continuous expeditions to the mountains, hoping to snide, surround and defeat the Ligurians (taking care not to be destroyed by ambushes). Throughout the war the Romans boasted 15 triumphs and at least one serious defeat.

Historically, the beginning of the campaign dates back to 193 BC on the initiative of the Ligurian conciliabula (federations), who organized a major raid going as far as the right bank of the river Arno. Roman campaigns followed (191, 188 and 187 B.C.), victorious but not decisive.

With the campaign of 186 B.C., the Romans were beaten by the Ligurians in the Magra valley. In the battle, which took place in a narrow and precipitous place, the Romans lost about 4000 soldiers, three eagle insignia of the second legion and eleven banners of the Latin allies. In addition, the consul Quintus Martius was also killed in the battle. It is thought that the place of the battle and the death of the consul gave rise to the place-name of Marciaso or that of the Canal of March on Mount Caprione in the town of Lerici and near the ruins of the city of Luni, which was later founded by the Romans. This mountain had a strategic importance because it controlled the valley of Magra and the sea.

In 185 B.C., the Ingauni and the Intimeli also rebelled and managed to resist the Roman legions until 180 B.C. The Apuani, and those of hinterland side still resisted.

Wanting to "dispose" of Liguria for their next conquest of Gaul, however, the Romans prepared a large army of almost 36,000 soldiers, under the orders of the Roman proconsuls Publius Cornelius Cethegus and Marcus Baebius Tamphilus, with the aim of putting an end to Ligurian independence.

In 180 B.C. the Romans inflicted a very serious defeat on the Apuani Ligures, and deported 40,000 of them to the regions of Samnium. This deportation was followed by another one of 7,000 Ligurians in the following year. These were one of the few cases in which the Romans deported defeated populations in such a high number. In 177 B.C. other groups of Liguri Apuani surrendered to the Roman forces, and eventually assimilated into Roman culture during the 2nd century BC[62], while the military campaign continued further north.

The surviving Ligurian tribes, now isolated and in absolute inferiority, continued to fight.

In succession: Frinatiates (175 B.C.), Statielli (172 B.C.), and the Velleiates (158 B.C.), had to surrender. The last Apuani resistance was won only in 155 B.C. by the consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus.

Subjugation of "transalpine" and "Capillati" Ligures

The subjugation of the coastal Ligures and the annexation of the Alpes Maritimae took place in 14 BC, closely following the occupation of the central Alps in 15 BC.[63]

The last Ligurian tribes (e.g. Vocontii and Salluvi) still autonomous, who occupied Provence, were subdued in 124 BC.[64]

Under Roman rule

The Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul

The Cisalpine Gaul was the part of modern Italy inhabited by Celts during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Conquered by the Roman Republic in the 220s BC, it was a Roman province from c. 81 BC until 42 BC, when it was merged into Roman Italy as indicated in Caesar's will (Acta Caesaris).[65][66] Until that time, it was considered part of Gaul, precisely that part of Gaul on the "hither side of the Alps" (from the perspective of the Romans), as opposed to Transalpine Gaul ("on the far side of the Alps").[67]

Gallia Cisalpina was further subdivided into Gallia Cispadana and Gallia Transpadana, i.e. its portions south and north of the Po River, respectively. The Roman province of the 1st century BC was bounded on the north and west by the Alps, in the south as far as Placentia by the river Po, and then by the Apennines and the river Rubicon, and in the east by the Adriatic Sea.[68] In 49 BC all inhabitants of Cisalpine Gaul received Roman citizenship[69]

The Regio IX Liguria

Around 7 BC, Augustus divided Italy into eleven regiones, as reported by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia. The ex-province of Gallia cisalpina was divided among four of the eleven regions of Italy: Regio VIII Gallia Cispadana, Regio IX Liguria, Regio X Venetia et Histria and Regio XI Gallia Transpadana.[70] One of this was The Regio IX Liguria, in 6 A.D. Genoa became the centre of this region and the Ligurian populations moved towards the definitive Romanisation.

The official historical name did not have the Liguria apposition, due to the contemporary academic use of naming the Augustan regions according to the populations they understood. Royal IX included only the Ligurian territory. This territory extended from the Maritime and Cottian Alps and the Var river (to the west) to the Trebbia and the Magra bordering Regio VIII Aemilia and Regio VII Etruria (to the east), and the Po to North.[71]

The description of the IX regio Italiae goes back to Pliny[72]: "patet ora Liguriae inter amnes Varum et Macram XXXI Milia passuum. Haec regio ex descriptione Augusti nona est".

This region was smaller than the original area occupied by the Ligurians in more ancient times: it was probably that in this province the purest Ligurian ethnicity was still preserved, while in nearbies Regio XI Transpadana (North of Po river) and in Provence the tribes were heavy celtised.

People with Ligurian names were living south of Placentia, in Italy, as late as 102 AD.[15]

In 126 A.D. the Liguria region was the birthplace of Pertinax, Roman soldier and politician who became Roman Emperor.

The Kingdom of Cottius

The area of the Alpes Cottiae province, named after Cottiust, the local king of Ligurian tribe of Segusini, who initially resisted Augustus' imperialism but eventually submitted and became the emperor's ally and personal friend. His territory, together with that of the other Alpine tribes, was annexed to the Roman empire in 15 BC - although Cottius, and his son after him, were accorded the unusual privilege of continuing to govern the region, with the title of praefectus i.e. Roman governor.[73] In 8 BC, Cottius showed his gratitude for this reprieve from dynastic oblivion by erecting a triumphal arch to Augustus in his capital, Segusio (Susa, Piedmont, Italy), which still stands. After the death of Cottius' son, the emperor Nero (ruled 54-68) appointed a regular equestrian procurator to govern the province.[74]

Ancient source

Aeschylus, in a fragment of Prometheus Unbound, represents Hercules as contending with the Ligures on the stony plains, near the mouths of the Rhone, and Herodotus speaks of Ligures inhabiting the country above Massilia (modern Marseilles, founded by the Greeks).

Thucydides also speaks of the Ligures having expelled the Sicanians, an Iberian tribe, from the banks of the river Sicanus, in Iberia.[75]

The Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax describes the Ligyes (Ligures) as living along the Mediterranean coast from Antion (Antibes) as far as the mouth of the Rhone and then intermingled with the Iberians from the Rhone to Emporion in Spain.[76]

Modern theories on origins

Traditional accounts suggested that the Ligures represented the northern branch of an ethno-linguistic layer older than, and very different from, the proto-Italic peoples. It was widely believed that a "Ligurian-Sicanian" culture occupied a wide area of southern Europe,[77] stretching from Liguria to Sicily and Iberia. However, while any such area would be broadly similar to that of the paleo-European "Tyrrhenian culture" hypothesized by later modern scholars, there are no known links between the Tyrrenians and Ligurians.

In the 19th century, the origins of the Ligures drew renewed attention from scholars. Amédée Thierry, a French historian, linked them to the Iberians,[78] while Karl Müllenhoff, professor of Germanic antiquities at the Universities of Kiel and Berlin, studying the sources of the Ora maritima by Avienus (a Latin poet who lived in the 4th century AD, but who used as a source for his own work a Phoenician Periplum of the 6th century BC),[79] held that the name 'Ligurians' generically referred to various peoples who lived in Western Europe, including the Celts, but thought the "real Ligurians" were a Pre-Indo-European population.[80]

Italian geologist and paleontologist Arturo Issel considered Ligurians to be direct descendants of the Cro-Magnon people that lived throughout Gaul from the Mesolithic period.[81]

Dominique-François-Louis Roget, Baron de Belloguet, claimed a "Gallic" origin of the Ligurians.[82] During the Iron Age the spoken language, the main divinities and the workmanship of the artifacts unearthed in the area of Liguria (such as the numerous torcs found) were similar to those of Celtic culture in both style and type.[83]

Those in favor of an Indo-European origin included Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, a 19th-century French historian, who argued in Les Premiers habitants de l'Europe that the Ligurians were the earliest Indo-European speakers of Western Europe. Jubainville's "Celto-Ligurian hypothesis", as it later became known, was significantly expanded in the second edition of his initial study. It inspired a body of contemporary philological research, as well as some archaeological work. The Celto-Ligurian hypothesis became associated with the Funnelbeaker culture and "expanded to cover much of Central Europe".[84]

Julius Pokorny adapted the Celto-Ligurian hypothesis into one linking the Ligures to the Illyrians, citing an array of similar evidence from Eastern Europe. Under this theory the "Ligures-Illyrians" became associated with the prehistoric Urnfield peoples.[85]

There are others such as Dominique Garcia, who question whether the Ligures can be considered a distinct ethnic group or culture from the surrounding cultures.[86][87]

Society

The Ligurians never formed a centralized state, they were in fact divided into independent tribes, in turn organized in small villages or castles. Rare were the oppidas, to which corresponded the federal capitals of the individual tribes or important commercial emporiums.

The territory of a tribe was almost entirely public property, only a small percentage of the land (the cultivated) was "private", in the sense that, against payment of a small tax, was given in concession. Only late in life did the concept of private, heritable or marketable property develop.

Reflecting the decentralized character of the ethnic group, the Ligurians did not have a centralized political structure. Each tribe decided for itself, even in contrast with the other tribes; as evidence of this, are the opposing alliances that over time Ligurian tribes made against Greeks, Etruscans and Romans.

Within the tribes, an egalitarian and communal spirit prevailed. If there was also a noble class, this was tempered by "tribal rallies" in which all the classes participated; there does not seem to have been any pre-organized magistracy. There were no dynastic leaders either: the Ligurian "king" was elected as leader of a tribe or a federation of tribes; only in late period did a real dynastic aristocratic class begin to emerge. Originally there was no slavery: prisoners of war were massacred or sacrificed.[88]

The stories of the foundation of Massalia, give us some interesting information:

- they had a strong sense of hospitality;

- the women chose each other's husbands, demonstrating an emancipation unknown to the eastern peoples.

Diodorus Siculus, in the first century B.C., writes that women take part in the work of toil alongside men.[89]

Clothing

Diodorus Siculus reports the use of a tunic tightened at the waist by a leather belt and closed by a clasp generally bronze; the legs were naked[90]. Other garments used were cloaks "sagum", and during the winter animal skins to shelter from the cold.[91] Characteristic element was the fibula, used to close the clothes and the cloaks, made of amber (imported from the Baltic) and glass paste, enriched with ornamental elements in bone or stone.

Physical appearance

Lucan in his Pharsalia (c. 61 AD) described Ligurian tribes as being long-haired, and their hair a shade of auburn (a reddish-brown):

...Ligurian tribes, now shorn, in ancient days

First of the long-haired nations, on whose necks

Once flowed the auburn locks in pride supreme.[92]

Warfare

Diodorus Siculus describes the Ligurians as very fearsome enemies: although not particularly impressive from the physical point of view, strength, will and tenacity makes them the most dangerous warriors than the gauls. As proof of this, the Ligurian warriors were very much in demand as mercenaries and several times the Mediterranean powers like Carthage and Syracuse, went to Liguria to recruit armies for their expeditions (for example, the elite troops of Hannibal were made up of a contingent of Ligurians).

Tactics, unit types and equipment

The armament varied according to the class and the comfort of the owner, in general however the great mass of the Ligurian warriors was substantially light infantry, armed in a poor way[91][93] The main weapon was the spear, with cusps that could exceed a cubit (about 45 cm, or one and half foot ), followed by the sword, of Gallic shape (sometimes cheap because made with soft metals), very rarely the warriors were equipped with bows and arrows.

The protection was entrusted to an oblong shield of wood,[94] always of Celtic typology (but to difference of this last one without metallic boss)[95] and a simple helmet, of Montefortino type.

The horned helmets, recovered in the Apuani tribe area, were problaby used only for ceremonial purpose and they were worn by warchief, to underline their virility and military skills. The use of armor is not known: the seated warrior from the site of Roquepertuse seems to wears a leather armor, although the statue is attributable to the 5th century A.D. and the armor maybe was used only in this period. Even if it is possible that the richer warriors used armor in organic material like the Gauls[95] or the greek linothorax .[96]

The infantry was good both close combat as skirmishes but could fight hand-to-hand when necessary.

Cavalry

Strabo and Diodorus Siculus say they fought almost on foot, because of the nature of their territory, but their phrasing implies that cavalry were not entirely unknown, and two recently discovered Ligurian graves have included harness fittings. Strabo says that the Salyes tribe located north of Massalia, have a substantial cavaly force, but, they were one of the several Celto-Ligurian tribes, and probably the cavalry reflect the Celtic element [90]

Mercenaries

The Ligures seem to have been ready to engage as mercenary troops in the service of others. Ligurian auxiliaries are mentioned in the army of the Carthaginian general Hamilcar I in 480 BC.[97] Greek leaders in Sicily continued to recruit Ligurian mercenary forces from the same quarter as late as the time of Agathocles.[75][98]

The mercenary trade was a particular form of trade and income: as the Greek and Roman sources attest, from very ancient times the Ligurians served as mercenaries in the armies of the western Mediterranean. The enlistment took place by contingents (obviously not for individual soldiers), as it was essential to have well-functioning units. Centuries of war experiences in the wars between Massaliotes, Etruscans, Carthaginians, Gauls, provided the Ligurians with war skills such as to keep the Roman armies in check for several decades.

Piracy

In ancient times, a side activity to the seafaring was piracy, and the Ligurians were no exception. If they thought it was appropriate, they attacked and plundered ships sailing along the coast. The thing is not surprising: even in ancient times the fastest way to obtain goods is to steal them. After all, the continuous raids of the Ligurian tribes in the territories of the neighbouring peoples are well documented, and constitute an important voice in their economy. The Ingauni, a tribe of sailors located around Albingaunum (nowadays Albenga) were famous to engage trade and piracy, hostiles to Rome[99], they were subdued by consul Lucius Emilius Paullus Macedonicus in 181 BC.[100]

Under Roman service

After the Roman conquest, in the 171-168 some of they combated with Romans against Macedons, by the time of Gaius Marius they became commoner in Roman army.

According to Plutarch the Battle of Pydna, the decisive battle of Third Macedonian War, started in the afternoon, for an artifice devised by Roman consul L.Emillius Paullus. In order to make the enemies move in battle first, he pushed before a horse without reins the Romans threw him against them, and the pursuit of the horse began the attack. According to another theory instead, the Thracians in Macedon service, attacked some Roman foragers getting a little too close to enemy lines, and in response there was the immediate charge of 700 Ligurian auxiliares [101].

Before Pydna the Romans used their Ligurian auxiliares with the velites for chasing off the Macedonian skimishers (the peltasts)[90]

Sallustius and Plutarch say that during the Jugurthine War (from 112 to 105 BC)[102] and the Cimbrian War (from 104 to 101 BC)[103] the Ligurians served as auxiliary troops in the Roman army. In the course of this last conflict they played an important role in the Battle of Aquae Sextae.

Ligures in its broad sense included all the Ligurian peoples of north western Italy, south eastern Gaul and the western Alps, however because Regio Liguria was annexed to Italia, the inhabitants of this region became Roman citizens, and would have been recruited into the legions. Therefore, the Alpine Ligures, who were peregrini (non-citizens) i.e. the inhabitants of the Alpes Cottiae and Alpes Maritimae, were recruited like Roman auxiliaries in the Ligurum cohorts.

Religion

Among the most important testimonies, the sacred mountain sites (Mont Bègo, Monte Beigua) and the development of megalithicism (statues-stelae of Lunigiana) are worth mentioning.

The spectacular Mont Bégo in Vallée des merveilles is the most representative site of the numerous sacred sites covered with rock carvings, and in particular with cupels, gullies and ritual basins. The latter would indicate that a fundamental part of the rites of the ancient Ligurians, provided for the use of water (or milk, blood?). The site of Mont Bégo has an extension and spectacularity comparable to the sites of Val Camonica. Another important sacred centre is Mount Beigua, but the reality is that many promontories in North-west Italy and the Alps present these types of sacred centres.

Among the more considerable Ligurian monuments are rock engravings and anthropomorphic sculptures analogous to those of southern France, found in Lunigiana and Corsica. Some of these artistic manifestations are repeated in territories farther east[104]

The other important evidence is the proliferation of megalithic events, the most spectacular and original of which is that of the stele statues in the Lunigiana. These particular oblong stones, stuck in the ground of the woods, ended with stylized human heads, and could be equipped with arms, sexual attributes and significant objects (e.g. daggers). Their real meaning has been lost in memory, today it is assumed that they represented:

- gods;

- ancestors and divinized heroes;

- the birth from the womb to symbolize the origin of their race originated directly from the womb of the earth and nature.

The heads, so represented, for the Ligurians were the seat of the soul, the center of emotions and the point of the body where all the senses were concentrated, consequently the essence of the divine and hence its cult.

In general, it is believed that the Ligurian religion was rather primitive, addressed to supernatural tutelary gods, representing the great forces of nature, and from which you could get help and protection through their divination.

The proliferation of sacred centers near the peaks, would indicate the cult of majestic celestial numes, represented by the high peaks: in fact Beg- (from which Baginus and Baginatie), Penn- (later transformed by Romanization in Iuppiter Poeninus and in the Apenninus pater) and Alb- (from which Albiorix) are indicated as tutelary numes of the Ligurian peaks.

Numbers such as Belenus and Borvo, linked to the cult of water, and the cult of Matronae (hence the sanctuary of Mons Matrona, now Montgenèvre) are also mentioned.

Among the many engravings, significant is the presence of the figure of the bull, even if only stylized through the symbol of the horns, this would indicate the cult of a deity taurine, male and fertilizer, already known to Anatolian and Semitic cultures.

Another important deity was Cicnu (the swan), which perhaps represents the divinization of a mythical ancient king or, as for many northern cultures, the totemic animal associated with the cult of the sun.

Thanks to the long contact with the Celtic populations, probably the Ligurians acquired beliefs and myths coming from that world. Surely, starting from the seventh century BC, the funerary outfits are similar to those found in populations of Celtic culture.

Economy

The Ligurian economy was based on primitive agriculture, sheep farming, hunting and the exploitation of forests. Diodorus Siculus writes about the Ligurians:

"Since their country is mountainous and full of trees, some of them use all day to cut wood, using strong and heavy dark; others, who want to cultivate the land, must deal with breaking stones, because it is so dry soil that you can not pick tools remove a sod, that with it do not rise stones. However, even if they have to fight with so many misfortunes, by means of stubborn work they go beyond nature [...] they often give themselves to hunting, and finding quantities of savage, with it they make up for the lack of bladders; and so it comes, that flowing through their snow-covered mountains, and getting used to practicing then more difficult places of the thickets, they harden their bodies, and strengthen their muscles admirably. Some of them, due to the famine of food, drink water, and live of meat of domestic and wild animals.[105]

Thanks to the contact with the bronze "metal seekers", the Ligurians also dedicated themselves to the extraction of minerals[106] and metallurgy, even if most of the metal in circulation is of central European origin.

The commercial activity is important. Already in ancient times the Ligurians were known in the Mediterranean for the trade of the precious Baltic amber. With the development of the Celtic populations, the Ligurians found themselves controlling a crucial access to the sea, becoming (sometimes in spite of themselves) custodians of an important way of communication.

Although they were not renowned navigators, they came to have a small maritime fleet, and their attitude to navigation is described as follows:

"They sail for reason of shops on the sea of Sardinia and Libya, spontaneously exposing themselves to extreme dangers; they use smaller hulls than vulgar boats for this; nor are they practical of the comfort of other ships; and what is surprising is that they are not afraid to sustain the serious risks of storms.[105]

Tribes

See also

- List of ancient Ligurian tribes

- Ancient peoples of Italy

- Mont Bègo

- Golasecca Culture

- Cisalpine Gaul

- Torrean civilization

References

- Maggiani, Adriano (2004). "Popoli e culture dell'Italia preromana. I Liguri". Il Mondo dell'Archeologia (in Italian). Rome: Treccani editore. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

Alla relativa abbondanza delle fonti letterarie circa queste popolazioni, che una parte della critica storiografica di tradizione ottocentesca voleva estese dal Magra all’Ebro, non corrisponde un panorama archeologico altrettanto ricco, che anzi, anche all’interno della Liguria storica, è ben lungi dal presentare caratteri unitari.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ligurian

- Francisco Villar, Los Indoeuropeos y los origines de Europa: lenguaje e historia, Madrid, Gredos, 1991,

- "Ligures en España" Martín Almagro Basch

- "Liguri". Enciclopedie on line. Treccani.it (in Italian). Rome: Treccani -Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. 2011.

Le documentazioni sulla lingua dei Liguri non ne permettono una classificazione linguistica certa (preindoeuropeo di tipo mediterraneo? Indoeuropeo di tipo celtico?).

- "Ligurian language". Britannica.com. 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2015-08-29.

- Baldi, Philip (2002). The Foundations of Latin. Walter de Gruyter. p. 112.

- The suffixes -asca or -asco do not appear to be related to the Celtic -brac, possibly meaning "swamp".

- "DicoLatin". DicoLatin.

- Room, "Placenames of the World," 2006

- Marie Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, Premiers Habitants de l'Europe (2nd edition 1889-1894)

- "Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^Xavier Delamarre, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Errance, 2003, p. 201.

- Montclos, Jean-Marie Pérouse de (1997). Châteaux of the Loire Valley. Könemann. ISBN 978-3-89508-598-7. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- Boardman, John (1988). The Cambridge ancient history: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean c. 525–479 BC. p. 716.

- Strabo, Geography, book 2, chapter 5, section 28.

- Bietti Sestieri 2010, p. 21.

- An Early History of Horsemanship pg.129

- ^Cfr. Rivista archeologica della provincia e antica diocesi di Como, 1908, p. 135; Emilia preromana vol. 8-10, 1980, p. 69; Istituto internazionale di studi liguri, Studi genuensi, vol. 9-15, 1991, p. 27.

- Fausto Cantarelli, I tempi alimentari del Mediterraneo: cultura ed economia nella storia alimentare dell'uomo, vol. 1, 2005, p. 172.

- Daiches, David; Anthony Thorlby (1972). Literature and western civilization (illustrated ed.). Aldus. p. 78.

- Cfr. la voce fossa in Alberto Nocentini, l'Etimologico. Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana, Firenze, Le Monnier, 2010. ISBN 978-88-0020-781-2.

- Ducato di Piazza Pontida

- "History of Brescia: the origins and the Roman Brescia". turismobrescia.it. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- "Storia del Colle Cidneo" [History of the Cidneo Hill]. bresciamusei.com (in Italian). Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- "Ducato di Piazza Pontida". www.ducatodipiazzapontida.it. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- "Le origini". www.bresciastory.it. Brescia Story. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Enciclopedia dell'arte antica , Polada- P.Palmieri(1965)

- Strabo, Geography, book 2, chapter 5, section 28.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Peregrine, Anthony (14 October 2015). "Marseille city break guide". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Duchêne & Contrucci 1998, p. 42.

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.13.6

- Duboi, Marius; Gaffarel, Paul; Samat, J.-B. (1913). Histoire de Marseille (in French). Marseille: Librairie P. Ruat.

- Duboi, Marius; Gaffarel, Paul; Samat, J.-B. (1913). Histoire de Marseille (in French). Marseille: Librairie P. Ruat.

- Robb, Graham, The Discovery of Middle Earth, p. 6

- Duboi, Marius; Gaffarel, Paul; Samat, J.-B. (1913). Histoire de Marseille (in French). Marseille: Librairie P. Ruat.

- J. R. Palanque, Ligures, Celts et Grecs, in Histoire de la Provence. Pg. 34

- J. R. Palanque, Ligures, Celts et Grecs, in Histoire de la Provence. Pg. 34.

- J. R. Palanque, Ligures, Celts et Grecs, in Histoire de la Provence. Pg. 34.

- Ptolemy's Geography online

- Mastino, Attilio(2006) Corsica e Sardegna in età antica(in Italian)

- Ugas 2005, p. 13-19.

- "Haec ipsa insula saepe iam cultores mutauit. Vt antiquiora, quae uetustas obduxit, transeam, Phocide relicta Graii qui nunc Massiliam incolunt prius in hac insula consederunt, ex qua quid eos fugauerit incertum est, utrum caeli grauitas an praepotentis Italiae conspectus an natura inportuosi maris; nam in causa non fuisse feritatem accolarum eo apparet quod maxime tunc trucibus et inconditis Galliae populis se interposuerunt. Transierunt deinde Ligures in eam, transierunt et Hispani, quod ex similitudine ritus apparet; eadem enim tegmenta capitum idemque genus calciamenti quod Cantabris est, et uerba quaedam; nam totus sermo conuersatione Graecorum Ligurumque a patrio desciuit." Seneca, Ad Helviam matrem de consolatione, VII, The Latin Library

- Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei celti. La nascita, l'affermazione e la decadenza, Newton & Compton, 2003, ISBN 88-8289-851-2, ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9

- "The Golasecca civilization is therefore the expression of the oldest Celts of Italy and included several groups that had the name of Insubres, Laevi, Lepontii, Oromobii (o Orumbovii)". (Raffaele C. De Marinis)

- ">Maps of the Golasecca culture". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- G. Frigerio, Il territorio comasco dall'età della pietra alla fine dell'età del bronzo, in Como nell'antichità, Società Archeologica Comense, Como 1987.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 52–56.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). pp. 24–37.

- "Ligurian and Celto-Ligurian tombs of the Lombard lakes region, often holding cremations, reveal a special iron culture called the culture of Golasecca" https://www.britannica.com/topic/ancient-Italic-people/Other-Italic-peoples#ref63581

- Ancient Italic people, The Ligurians, Enciclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/ancient-Italic-people/Other-Italic-peoples#ref63581

- La Battaglia del mare Sardo (540 a.C.) Archiviato il 26 febbraio 2013 in Internet Archive..

- Marco Milanese, Scavi nell'oppidum preromano di Genova, L'Erma di Bretschneider, Roma 1987 testo on-line su GoogleBooks; Piera Melli , Una città portuale del Mediterraneo tra il VII e il III secolo a.C.", Genova, Fratelli Frilli ed., 2007.

- Piera Melli , Una città portuale del Mediterraneo tra il VII e il III secolo a.C.", Genoa, Fratelli Frilli ed., 2007 (on-line text of the first chapter Archived on 28 February 2009 in the Internet Archive.). A marble funerary stele dedicated to Apollonia, found reused in the walls of the twelfth century was considered a proof of the Greek origin of the city: the stele, a work of the first half of the third century BC, must be considered rather arrived in Genoa along with many ancient artifacts in the Middle Ages.

- Demandt, p. 86

- Polybius iii. 60, 8

- Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita libri CXLII 21, 32,1 and 28, 46,7.

- Polibius, Stories, XV, 11.1

- In 200 the Gauls and Ligurians combined forces and sacked the Latin colony of Placentia in an attempt to drive the Romans out of their lands https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome/Roman-expansion-in-the-western-Mediterranean#ref298396

- During the same period the Romans were at war with the Ligurian tribes of the northern Apennines. The serious effort began in 182, when both consular armies and a proconsular army were sent against the Ligurians. The wars continued into the 150s, when victorious generals celebrated two triumphs over the Ligurians. Here also the Romans drove many natives off their land and settled colonies in their stead (e.g., Luna and Luca in the 170s). https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome/Roman-expansion-in-the-western-Mediterranean#ref298396

- Broadhead, William (2002). Internal migration and the transformation of Republican Italy (PDF) (Ph.D.). University College London. p. 15.

- Dio LIV.22.3-4

- Plinius the elder, Naturalis Historia, III, 47.

- Long, George (1866). Decline of the Roman republic: Volume 2. London.

- Snith, William George (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography: Vol.1. Boston.

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1857). A manual of ancient geography. Philadelphia.

- Cassius Dio XLI, 36.

- Brouwer, Hendrik H. J. (1989). Hiera Kala: Images of animal sacrifice in archaic and classical Greece. Utrecht.

- Strabo, Geography, V, 1,1 and 2.1.

- Plinius the Elder, Naturalis Historia, III, 49.

- CAH X 170

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica Segusio

- William Smith, ed. (1854). "Liguria". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

- Shipley, Graham (2008). "The Periplous of Pseudo-Scylax: An Interim Translation".

- Sciarretta, Antonio (2010). Toponomastica d'Italia. Nomi di luoghi, storie di popoli antichi. Milano: Mursia. pp. 174–194. ISBN 978-88-425-4017-5.

- Amédée Thierry, Histoire des Gaulois depuis les temps les plus reculés.

- Postumius Rufius Festus (qui et) Avienius, Ora maritima, 129–133 (nel quale in modo oscuro indica i Liguri come abitanti a nord delle "isole oestrymniche"; 205 (Liguri a nord della città di Ophiussa nella penisola iberica); 284–285 (il fiume Tartesso nascerebbe dalle "paludi ligustine").

- Karl Viktor Müllenhoff, Deutsche Alterthurnskunde, I volume.

- Arturo Issel Liguria geologica e preistorica, Genoa 1892, II volume, pp. 356–357.

- Dominique François Louis Roget de Belloguet, Ethnogénie gauloise, ou Mémoires critiques sur l'origine et la parenté des Cimmériens, des Cimbres, des Ombres, des Belges, des Ligures et des anciens Celtes. Troisiéme partie. Preuves intellectuelles. Le génie gaulois, Paris 1868.

- Gilberto Oneto Paesaggio e architettura delle regioni padano-alpine dalle origini alla fine del primo millennio, Priuli e Verlucc, editori 2002, pp. 34–36, 49.

- See, in particular McEvedy, Colin (1967). The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History by Colin McEvedy. p. 29.

- Henning, Andersen (2003). Language Contacts in Prehistory: Studies in Stratigraphy. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 16–17.

- Garcia, Dominique (2012). From the Pillars of Hercules to the Footsteps of the Argonauts (Colloquia Antiqua). Peeters.

- Haeussler, Ralph (2013). Becoming Roman?: Diverging Identities and Experiences in Ancient Northwest Italy. Routledge. p. 87.

- Livius mentions the fate of the population of Mutina, once it fell into the hands of the Ligures.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, V, 39, 1.

- Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars, Duncan Head, 2012 Page 296 (https://books.google.it/books?id=-7n8CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA294&lpg=PA294&dq=ligures+warrior&source=bl&ots=1gcz-CPca-&sig=ACfU3U2IWz3f6FlupTDzRSNtwjrDZQvaRg&hl=it&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjF9dWTpurlAhUDKewKHfQvA1YQ6AEwBnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=ligures%20warrior&f=false)

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, V, 39, 1-8.

- Lucan, Pharsalia, I. 496, translated by Edward Ridley (1896).

- Livius XXXIX I, 6

- Polibius XXIX 14, 4

- "AD PUGNAM PARATI: Rievocazione Storica, Spettacolo, Sperimentazione" (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- The commercial contacts with the Greeks and the militancy of Ligurian mercenaries in the ranks of the Greek and Carthaginian armies of the western Mediterranean, who effectively used this type of protection, may have led to their adoption by the Ligurians.

- Herodotus 7.165; Diodorus Siculus 11.1.

- Diodorus Siculus 21.3.

- They were on Carthaginian side during the Second Punic War also.

- "Ingauni" on Enciclopedia Treccani http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ingauni

- Plutarch, The Lives of Emilius Paul and Timoleon XVIII

- Salustio, Giugurtine War (In French)

- Plutarch, Marius, 20

- Ancient Italic people, The Ligurians, Enciclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/ancient-Italic-people/Other-Italic-peoples#ref63581

- (Diodorus Siculus, in Luca Ponte, Le genovesi)

- Examples of mining activities are witnessed in the Labiola mine.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ligures. |

- ARSLAN E. A. 2004b, LVI.14 Garlasco, in I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, Catalogo della Mostra (Genova, 23.10.2004-23.1.2005), Milano-Ginevra, pp. 429–431.

- ARSLAN E. A. 2004 c.s., Liguri e Galli in Lomellina, in I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, Saggi Mostra (Genova, 23.10.2004–23.1.2005).

- Raffaele De Marinis, Giuseppina Spadea (a cura di), Ancora sui Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo, De Ferrari editore, Genova 2007 (scheda sul volume).

- John Patterson, Sanniti,Liguri e Romani,Comune di Circello;Benevento

- Giuseppina Spadea (a cura di), I Liguri. Un antico popolo europeo tra Alpi e Mediterraneo" (catalogo mostra, Genova 2004–2005), Skira editore, Genova 2004

Further reading

- Berthelot, André. "LES LIGURES." Revue Archéologique 2 (1933): 245-303. www.jstor.org/stable/41750896.