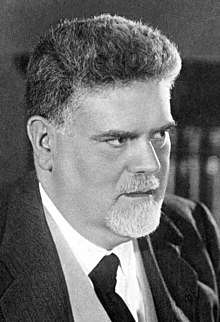

Giovanni Gentile

Giovanni Gentile (Italian: [dʒoˈvanni dʒenˈtiːle]; 30 May 1875 – 15 April 1944) was an Italian[3][4] neo-Hegelian idealist philosopher, educator, and fascist politician. The self-styled "philosopher of Fascism", he was influential in providing an intellectual foundation for Italian Fascism, and ghostwrote part of The Doctrine of Fascism (1932) with Benito Mussolini. He was involved in the resurgence of Hegelian idealism in Italian philosophy and also devised his own system of thought, which he called "actual idealism" or "actualism", which has been described as "the subjective extreme of the idealist tradition".[5][6][7]

Giovanni Gentile | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Royal Academy of Italy | |

| In office 25 July 1943 – 15 April 1944 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Luigi Federzoni |

| Succeeded by | Giotto Dainelli Dolfi |

| Minister of Public Education | |

| In office 31 October 1922 – 1 July 1924 | |

| Prime Minister | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Antonino Anile |

| Succeeded by | Alessandro Casati |

| Member of the Italian Senate | |

| In office 11 June 1921 – 5 August 1943 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 May 1875 Castelvetrano, Italy |

| Died | 15 April 1944 (aged 68) Florence, RSI |

| Resting place | Santa Croce, Florence, Italy |

| Political party | National Fascist Party (1923–1943) |

| Spouse(s) | Erminia Nudi

( m. 1901; |

| Children | 6 |

| Alma mater | Scuola Normale Superiore[1] University of Florence[1] |

| Profession | Teacher, philosopher, politician |

Philosophy career | |

Notable work | |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Hegelianism |

Main interests | Metaphysics, dialectics, pedagogy |

Notable ideas | Actual idealism, fascism, immanentism (method of immanence)[2] |

|

| Hegelianism |

|---|

| Forerunners |

| Successors |

| Principal works |

| Schools |

| Related topics |

| Related categories |

|

► Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel |

Biography

Early life and career

Giovanni Gentile was born in Castelvetrano, Sicily. He was inspired by Risorgimento-era Italian intellectuals such as Mazzini, Rosmini, Gioberti, and Spaventa from whom he borrowed the idea of autoctisi, "self-construction", but also was strongly influenced by the German idealist and materialist schools of thought – namely Karl Marx, Hegel, and Fichte, with whom he shared the ideal of creating a Wissenschaftslehre (Epistemology), a theory for a structure of knowledge that makes no assumptions. Friedrich Nietzsche, too, influenced him, as seen in an analogy between Nietzsche's Übermensch and Gentile's Uomo Fascista. In religion he presented himself as a Catholic (of sorts), and emphasised actual idealism's Christian heritage; Antonio G. Pesce insists that 'there is in fact no doubt that Gentile was a Catholic', but he occasionally identified himself as an atheist, albeit one who was still culturally a Catholic.[8][9]

He won a fierce competition to become one of four exceptional students of the prestigious Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, where he enrolled in the Faculty of Humanities.

During his academic career, Gentile served in a number of positions, including as:

- Professor of the History of Philosophy at the University of Palermo (27 March 1910);

- Professor of Theoretical Philosophy at the University of Pisa (9 August 1914);

- Professor of the History of Philosophy at the University of Rome (11 November 1917), and later as Professor of Theoretical Philosophy (1926);

- Commissioner of the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa (1928–32), and later as its Director (1932–43); and

- Vice President of Bocconi University in Milan (1934–44).

Involvement with Fascism

In 1922, Gentile was named Minister of Public Education for the government of Benito Mussolini. In this capacity he instituted the "Riforma Gentile" – a reformation of the secondary school system that had a long-lasting impact on Italian education.[10][11] His philosophical works included The Theory of Mind as Pure Act (1916) and Logic as Theory of Knowledge (1917), with which he defined actual idealism, a unified metaphysical system reinforcing his sentiments that philosophy isolated from life, and life isolated from philosophy, are but two identical modes of backward cultural bankruptcy. For Gentile, this theory indicated how philosophy could directly influence, mould, and penetrate life; or, how philosophy could govern life.

In 1925, Gentile headed two constitutional reform commissions that helped establish the corporate state of Fascism. He would go on to serve as president of the Fascist state's Grand Council of Public Education (1926–28), and even gained membership on the powerful Fascist Grand Council (1925–29).

Gentile's philosophical system – the foundation of all Fascist philosophy – viewed thought as all-embracing: no-one could actually leave his or her sphere of thought, nor exceed his or her thought. Reality was unthinkable, except in relation to the activity by means of which it becomes thinkable, positing that as a unity — held in the active subject and the discrete abstract phenomena that reality comprehends – wherein each phenomenon, when truly realised, was centered within that unity; therefore, it was innately spiritual, transcendent, and immanent, to all possible things in contact with the unity. Gentile used that philosophic frame to systematize every item of interest that now was subject to the rule of absolute self-identification – thus rendering as correct every consequence of the hypothesis. The resultant philosophy can be interpreted as an idealist foundation for Legal Naturalism.

Giovanni Gentile was described by Mussolini, and by himself, as "the philosopher of Fascism"; moreover, he was the ghostwriter of the first part of the essay The Doctrine of Fascism (1932), attributed to Mussolini.[12] It was first published in 1932, in the Italian Encyclopedia, wherein he described the traits characteristic of Italian Fascism at the time: compulsory state corporatism, Philosopher Kings, the abolition of the parliamentary system, and autarky. He also wrote the Manifesto of the Fascist Intellectuals which was signed by a number of writers and intellectuals, including Luigi Pirandello, Gabriele D'Annunzio, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Giuseppe Ungaretti.

Final years and death

Gentile became a member of the Fascist Grand Council in 1925, and remained loyal to Mussolini even after the fall of the Fascist government in 1943. He supported Mussolini's establishment of the "Republic of Salò", a puppet state of Nazi Germany, despite having criticized its anti-Jewish laws, and accepted an appointment in its government. Gentile was the last president of the Royal Academy of Italy (1943–1944).[13]

In 1944 a group of anti-fascist partisans, led by Bruno Fanciullacci, murdered the "philosopher of Fascism" as he returned from the prefecture in Florence, where he had been arguing for the release of anti-fascist intellectuals.[14] Gentile was buried in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.[15]

Philosophy

Benedetto Croce wrote that Gentile "... holds the honor of having been the most rigorous neo-Hegelian in the entire history of Western philosophy and the dishonor of having been the official philosopher of Fascism in Italy."[16] His philosophical basis for fascism was rooted in his understanding of ontology and epistemology, in which he found vindication for the rejection of individualism, and acceptance of collectivism, with the state as the ultimate location of authority and loyalty outside of which individuality had no meaning (and which in turn helped justify the totalitarian dimension of fascism).[17]

The conceptual relationship between Gentile's actual idealism and his conception of fascism is not self-evident. The supposed relationship does not appear to be based on logical deducibility. That is, actual idealism does not entail a fascist ideology in any rigorous sense. Gentile enjoyed fruitful intellectual relations with Croce from 1899 – and particularly during their joint editorship of La Critica from 1903 to 1922 – but broke philosophically and politically from Croce in the early 1920s over Gentile's embrace of fascism. (Croce assesses their philosophical disagreement in Una discussione tra filosofi amici in Conversazioni Critiche, II.)

Ultimately, Gentile foresaw a social order wherein opposites of all kinds weren't to be considered as existing independently from each other; that 'publicness' and 'privateness' as broad interpretations were currently false as imposed by all former kinds of government, including capitalism and communism; and that only the reciprocal totalitarian state of Corporatism, a fascist state, could defeat these problems which are made from reifying as an external reality that which is in fact, to Gentile, only a reality in thinking. Whereas it was common in the philosophy of the time to see the conditional subject as abstract and the object as concrete, Gentile postulated (after Hegel) the opposite, that the subject is concrete and the object a mere abstraction (or rather, that what was conventionally dubbed "subject" is in fact only conditional object, and that the true subject is the act of being or essence of the object).

Gentile was, because of his actualist system, a notable philosophical presence across Europe during his time. At its base, Gentile's brand of idealism asserted the primacy of the "pure act" of thinking. This act is foundational to all human experience – it creates the phenomenal world – and involves a process of "reflective awareness" (in Italian, "l'atto del pensiero, pensiero pensante") that is constitutive of the Absolute and revealed in education.[6] Gentile's emphasis on seeing Mind as the Absolute signaled his "revival of the idealist doctrine of the autonomy of the mind."[7] It also connected his philosophical work to his vocation as a teacher. In actual idealism, then, pedagogy is transcendental and provides the process by which the Absolute is revealed.[13] His idea of a transcending truth above positivism garnered particular attention by emphasizing that all modes of sensation only take the form of ideas within one's mind; in other words, they are mental constructs. To Gentile, for example, even the correlation of the function and location of the physical brain with the functions of the physical body was merely a consistent creation of the mind, and not of the brain (itself a creation of the mind). Observations like this have led some commentators to view Gentile's philosophy as a kind of "absolute solipsism," expressing the idea "that only the spirit or mind is real".[18]

Actual idealism also touches on ideas of concern to theology. An example of actual idealism in theology is the idea that although man may have invented the concept of God, it does not make God any less real in any possible sense, so long as God is not presupposed to exist as abstraction, and except in case qualities about what existence actually entails (i.e. being invented apart from the thinking that makes it) are presupposed. Benedetto Croce objected that Gentile's "pure act" is nothing other than Schopenhauer's will.[19]

Therefore, Gentile proposed a form of what he called "absolute Immanentism" in which the divine was the present conception of reality in the totality of one's individual thinking as an evolving, growing and dynamic process. Many times accused of solipsism, Gentile maintained his philosophy to be a Humanism that sensed the possibility of nothing beyond what was colligate in perception; the self's human thinking, in order to communicate as immanence is to be human like oneself, made a cohesive empathy of the self-same, without an external division, and therefore not modeled as objects to one's own thinking. Whereas solipsism would feel trapped in realization of its solitude, actualism rejects such a privation and is an expression of the only freedom which is possible within objective contingencies, where the transcendental Self does not even exist as an object, and the dialectical co-substantiation of others necessary to understand the empirical self are felt as true others when found to be the unrelativistic subjectivity of that whole self and essentially unified with the spirit of such higher self in actu, where others can be truly known, rather than thought as windowless monads.

Phases of his thought

A number of developments in Gentile's thought and career helped to define his philosophy, including:

- the definition of Actual Idealism in his work Theory of the Pure Act (1903);

- his support for the invasion of Libya (1911) and the entry of Italy into World War I (1915);

- his dispute with Benedetto Croce over the historic inevitability of Fascism;[20]

- his role as minister of education (1922–24);

- his belief that Fascism could be made subservient to his philosophical thought, along with his gathering of influence through the work of students like Armando Carlini (leader of the so-called "right Gentilians") and Ugo Spirito (who applied Gentile's philosophy to social problems and helped codify Fascist political theory); and

- his work on the Enciclopedia Italiana (1925–43; first edition finished in 1936).

Gentile's definition of and vision for Fascism

Gentile considered Fascism the fulfillment of the Risorgimento ideals[21], particularly those represented by Giuseppe Mazzini[22] and the Historical Right party.[23]

Gentile sought to make his philosophy the basis for Fascism.[24] However, with Gentile and with Fascism, the "problem of the party" existed by virtue of the fact that the Fascist "party", as such, arose organically rather than from a tract or pre-established socio-political doctrine. This complicated the matter for Gentile as it left no consensus to any way of thinking among Fascists, but ironically this aspect was to Gentile's view of how a state or party doctrine should live out its existence: with natural organic growth and dialectical opposition intact. The fact that Mussolini gave credence to Gentile's view points via Gentile's authorship helped with an official consideration, even though the "problem of the party" continued to exist for Mussolini as well.

Gentile placed himself within the Hegelian tradition, but also sought to distance himself from those views he considered erroneous. He criticized Hegel's dialectic (of Idea-Nature-Spirit), and instead proposed that everything is Spirit, with the dialectic residing in the pure act of thinking. Gentile believed Marx's conception of the dialectic to be the fundamental flaw of his application to system making. To the neo-Hegelian Gentile, Marx had made the dialectic into an external object, and therefore had abstracted it by making it part of a material process of historical development. The dialectic to Gentile could only be something of human precepts, something that is an active part of human thinking. It was, to Gentile, concrete subject and not abstract object. This Gentile expounded by how humans think in forms wherein one side of a dual opposite could not be thought of without its complement.

"Upward" wouldn't be known without "downward" and "heat" couldn't be known without "cold", while each are opposites they are co-dependent for either one's realization: these were creations that existed as dialectic only in human thinking and couldn't be confirmed outside of which, and especially could not be said to exist in a condition external to human thought like independent matter and a world outside of personal subjectivity or as an empirical reality when not conceived in unity and from the standpoint of the human mind.

To Gentile, Marx's externalizing of the dialectic was essentially a fetishistic mysticism. Though when viewed externally thus, it followed that Marx could then make claims to the effect of what state or condition the dialectic objectively existed in history, a posteriori of where any individual's opinion was while comporting oneself to the totalized whole of society. i.e. people themselves could by such a view be ideologically 'backwards' and left behind from the current state of the dialectic and not themselves be part of what is actively creating the dialectic as-it-is.

Gentile thought this was absurd, and that there was no 'positive' independently existing dialectical object. Rather, the dialectic was natural to the state, as-it-is. Meaning that the interests composing the state are composing the dialectic by their living organic process of holding oppositional views within that state, and unified therein. It being the mean condition of those interests as ever they exist. Even criminality is unified as a necessarily dialectic to be subsumed into the state and a creation and natural outlet of the dialectic of the positive state as ever it is.

This view (influenced by the Hegelian theory of the state) justified the corporative system, where in the individualized and particular interests of all divergent groups were to be personably incorporated into the state ("Stato etico") each to be considered a bureaucratic branch of the state itself and given official leverage. Gentile, rather than believing the private to be swallowed synthetically within the public as Marx would have it in his objective dialectic, believed that public and private were a priori identified with each other in an active and subjective dialectic: one could not be subsumed fully into the other as they already are beforehand the same. In such a manner each is the other after their own fashion and from their respective, relative, and reciprocal, position. Yet both constitute the state itself and neither are free from it, nothing ever being truly free from it, the state (as in Hegel) existing as an eternal condition and not an objective, abstract collection of atomistic values and facts of the particulars about what is positively governing the people at any given time.

Works

- On the Comedies of Antonfranceso Grazzi, "Il Lasca" (1896)

- A Criticism of Historical Materialism (1897)

- Rosmini and Gioberti (1898)

- The philosophy of Marx (1899)

- The Concept of History (1899)

- The teaching of philosophy in high schools (1900)

- The scientific concept of pedagogy (1900)

- On the Life and Writings of B. Spaventa (1900)

- Hegelian controversy (1902)

- Secondary school unit and freedom of studies (1902)

- Philosophy and empiricism (1902)

- The Rebirth of Idealism (1903)

- From Genovesi to Galluppi (1903)

- Studies on the Roman Stoicism of the 1st century BC (1904)

- High School Reforms (1905)

- The son of G. B. Vico (1905)

- The Reform of the Middle School (1906)

- The various editions of T. Campanella 's De sensu rerum (1906)

- Giordano Bruno in the History of Culture (1907)

- The first process of heresy of T. Campanella (1907)

- Vincenzo Gioberti in the first centenary of his birth (1907)

- The Concept of the History of Philosophy (1908)

- School and Philosophy (1908)

- Modernism and the Relationship between Religion and Philosophy (1909)

- Bernardino Telesio (1911)

- The Theory of Mind as Pure Act (1912)

- The Philosophical Library of Palermo (1912)

- On Current Idealism: Memories and Confessions (1913)

- The Problems of Schooling and Italian Thought (1913)

- Reform of Hegelian Dialectics (1913)

- Summary of Pedagogy as a Philosophical Science (1913)

- "The wrongs and the rights of positivism" (1914)

- "The Philosophy of War" (1914)

- Pascuale Galluppi, a Jacobine? (1914)

- Writings of life and ideas by V. Gioberti (1915)

- Donato Jaja (1915)

- The Bible of the Letters in Print by V. Gioberti (1915)

- Vichian Studies (1915)

- Pure experience and historical reality (1915)

- For the Reform of Philosophical Insights (1916)

- The concept of man in the Renaissance (1916)

- "The Foundations of the Philosophy of Law" (1916)

- General theory of the spirit as pure act (1916)

- The origins of contemporary philosophy in Italy (1917)

- System of logic as theory of knowledge (1917)

- The historical character of Italian philosophy (1918)

- Is there an Italian school? (1918)

- Marxism of Benedict Croce (1918)

- The sunset of Sicilian culture (1919)

- Mazzini (1919)

- The political realism of V. Gioberti (1919)

- War and Faith (1919)

- After the Victory (1920)

- The post-war school problem (1920)

- Reform of Education (1920)

- Discourses of Religion (1920)

- Giordano Bruno and the thought of the Renaissance (1920)

- Art and Religion (1920)

- Bertrando Spaventa (1920)

- Defense of Philosophy (1920)

- History of the Piedmontese culture of the 2nd half of the 16th century (1921)

- Fragments of Aesthetics and Literature (1921)

- Glimmers of the New Italy (1921)

- Education and the secular school (1921)

- Critical Essays (1921)

- The philosophy of Dante (1921)

- The modern concept of science and the university problem (1921)

- G. Capponi and the Tuscan culture of the 20th century (1922)

- Studies on the Renaissance (1923)

- "Dante and Manzoni, an essay on Art and Religion" (1923)

- "The Prophets of the Italian Risorgimento" (1923)

- On the Logic of the Concrete (1924)

- "Preliminaries in the Study of the Child" (1924)

- School Reform (1924)

- Fascism and Sicily (1924)

- Fascism to the Government of the School (1924)

- What is fascism (1925)

- The New Middle School (1925)

- Current Warnings (1926)

- Fragments of History of Philosophy (1926)

- Critical Essays (1926)

- The Legacy of Vittorio Alfieri (1926)

- Fascist Culture (1926)

- The religious problem in Italy (1927)

- Italian thought of the nineteenth century (1928)

- Fascism and Culture (1928)

- The Philosophy of Fascism (1928)

- "The Great Council's Law" (1928)

- Manzoni and Leopardi (1929)

- Origins and Doctrine of Fascism (1929)

- The philosophy of art (1931)

- The Reform of the School in Italy (1932)

- Introduction to Philosophy (1933)

- The Woman and the Child (1934)

- "Origins and Doctrine of Fascism" (1934)

- Economics and Ethics (1934)

- Leonardo da Vinci (Gentile was one of the contributors, 1935)

Collected works

Systematic works

- I–II. Summary of pedagogy as a philosophical science (Vol. I: General pedagogy; vol. II: Teaching).

- III. The general theory of the spirit as pure act.

- IV. The foundations of the philosophy of law.

- V–VI. The System of Logic as Theory of Knowledge (Vol. 2).

- VII. Reform of education.

- VIII. The philosophy of art.

- IX. Genesis and structure of society.

Historical works

- X. History of philosophy. From the origins to Plato.

- XI. History of Italian philosophy (up to Lorenzo Valla).

- XII. The Problems of Schooling and Italian Thinking.

- XIII. Studies on Dante.

- XIV The Italian thought of the Renaissance.

- XV. Studies on the Renaissance.

- XVI. Vichian Studies.

- XVII. The legacy of Vittorio Alfieri.

- XVIII–XIX. History of Italian philosophy from Genovesi to Galluppi (vol.2).

- XXXXI. Albori of the new Italy (vol.2).

- XXII. Vincenzo Cook. Studies and notes.

- XXIII. Gino Capponi and Tuscan culture in the decimony of the century.

- XXIV. Manzoni and Leopardi.

- XXV. Rosmini and Gioberti.

- XXVI. The prophets of the Italian Risorgimento.

- XXVII. Reform of Hegelian Dialectics.

- XXVIII. Marx's philosophy.

- XXIX. Bertrando Spaventa.

- XXX. The sunset of the Sicilian culture.

- XXXI-XXXIV. The origins of contemporary philosophy in Italy. (Vol. I: Platonists, Vol II: Positivists, Vol III and IV: Neo-Kantians and Hegelians).

- XXXV. Modernism and the relationship between religion and philosophy.

Various works

- XXXVI. Introduction to philosophy.

- XXXVII. Religious Speeches.

- XXXVIII. Defense of philosophy.

- XXXIX. Education and lay school.

- XL. The new middle school.

- XLI. School Reform in Italy.

- XLII. Preliminaries in the study of the child.

- XLIII. War and Faith.

- XLIV. After the win.

- XLV-XLVI. Politics and Culture (Vol. 2).

Letter collections

- I–II. Letter from Gentile-Jaja (Vol. 2)

- III–VII. Letters to Benedetto Croce (Vol. 5)

- VIII. Letter from Gentile-D'Ancona

- IX. Letter from Gentile-Omodeo

- X. Letter from Gentile-Maturi

- XI. Letter from Gentile-Pintor

- XII. Letter from Gentile-Chiavacci

- XIII. Letter from Gentile-Calogero

- XIV. Letter from Gentile-Donati

Notes

- Gregor, 2001, p. 1.

- Gentile's so-called method of immanence "attempted to avoid: (1) the postulate of an independently existing world or a Kantian Ding-an-sich (thing-in-itself), and (2) the tendency of neo-Hegelian philosophy to lose the particular self in an Absolute that amounts to a kind of mystical reality without distinctions" (M. E. Moss, Mussolini's Fascist Philosopher: Giovanni Gentile Reconsidered, Peter Lang, p. 7).

- "Giovanni Gentile | Italian philosopher".

- "Giovanni Gentile, un Italiano nelle intemperie".

- Gentile, Giovanni. "The Theory of Mind as Pure Act". archive.org. Translated by H. Wildon Carr. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. p. xii. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- Harris, H.S. (1967). "Gentile, Giovanni (1875-1944)". In Gale, Thomas (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy – via Encyclopedia.com.

- "Giovanni Gentile". Encyclopedia of World Biography. The Gale Group, Inc. 2004 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- James Wakefield, Giovanni Gentile and the State of Contemporary Constructivism: A Study of Actual Idealist Moral Theory, Andrews UK Limited, 2015, note 53.

- Giovanni Gentile, Le ragioni del mio ateismo e la storia del cristianesimo, Giornale critico della filosofia italiana, n. 3, 1922, pp. 325–28.

- Richard J. Wolff, Catholicism, Fascism and Italian Education from the Riforma Gentile to the Carta Della Scuola 1922–1939, History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1980, pp. 3–26.

- Riforma Gentile on Italian Wikipedia.

- "The first half of the article was the work of Giovanni Gentile; only the second half was Mussolini's own work, though the whole article appeared under his name." Adrian Lyttelton, Italian Fascisms: from Pareto to Gentile, 13.

- "Giovanni Gentile | Italian philosopher". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- Bruno Fanciullacci on Italian Wikipedia. The surname Fanciullacci translates as "bad kids" in English, a coincidental irony given Gentile's actualism proposed the identity of philosophy, political action, and paedagogy.

- "Giovanni Gentile". Italy On This Day. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- Benedetto Croce, Guide to Aesthetics, Translated by Patrick Romanell, "Translator's Introduction," The Library of Liberal Arts, The Bobbs–Merrill Co., Inc., 1965

- Mussolini – THE DOCTRINE OF FASCISM. www.worldfuturefund.org. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- Gentile, Giovanni (1 January 2008). The Theory of Mind as Pure Act. Living Time Press. ISBN 9781905820375.

- Runes, Dagobert, editor, Treasure of Philosophy, "Gentile, Giovanni"

- "Croce and Gentile," The Living Age, 19 September 1925.

- From Myth to Reality and Back Again: The Fascist and Post-Fascist Reading of Garibaldi and the Risorgimento

- M. E. Moss (2004) Mussolini's Fascist Philosopher: Giovanni Gentile Reconsidered; New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.; p. 58-60

- Italian Mathematics Between the Two World Wars.

- The Philosophical Basis of Fascism By Sir Giovanni Gentile.

References

- A. James Gregor, Giovanni Gentile: Philosopher of Fascism. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2001.

Further reading

English

- Angelo Crespi, Contemporary Thought of Italy, Williams and Norgate, Limited, 1926.

- L. Minio-Paluello, Education in Fascist Italy, Oxford University Press, 1946.

- Treasury of Philosophy, edited by Dagobert D. Runes, Philosophical Library, New York, 1955.

- David D. Roberts, Historicism and Fascism in Modern Italy, University of Toronto Press, 2007.

- Adrian Lyttleton, ed., Italian Fascisms: From Pareto to Gentile (Harper & Row, 1973).

- A. James Gregor, "Giovanni Gentile and the Philosophy of the Young Karl Marx," Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 24, No. 2 (April–June 1963).

- A. James Gregor, Origins and Doctrine of Fascism: With Selections from Other Works by Giovanni Gentile. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2004.

- A. James Gregor, Mussolini's Intellectuals: Fascist Social and Political Thought, Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Aline Lion, The Idealistic Conception of Religion; Vico, Hegel, Gentile (Oxford, The Clarendon Press, 1932).

- Gabriele Turi, "Giovanni Gentile: Oblivion, Remembrance, and Criticism," The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 70, No. 4 (December 1998).

- George de Santillana, "The Idealism of Giovanni Gentile," Isis, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Nov. 1938).

- Giovanni Gullace, "The Dante Studies of Giovanni Gentile," Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society, No. 90 (1972).

- Guido de Ruggiero, "G. Gentile: Absolute Idealism." In Modern Philosophy, Part IV, Chap. III, (George Allen & Unwin, 1921).

- H. S. Harris, The Social Philosophy of Giovanni Gentile (U. of Illinois Press, 1966).

- Irving Louis Horowitz, "On the Social Theories of Giovanni Gentile," Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Dec. 1962).

- J. A. Smith, "The Philosophy of Giovanni Gentile," Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol. 20, (1919–1920).

- M. E. Moss, Mussolini's Fascist Philosopher, Giovanni Gentile Reconsidered (Lang, 2004).

- Merle E. Brown, Neo-idealistic Aesthetics: Croce-Gentile-Collingwood (Wayne State University Press, 1966).

- Merle E. Brown, "Respice Finem: The Literary Criticism of Giovanni Gentile," Italica, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Spring, 1970).

- Merritt Moore Thompson, The Educational Philosophy of Giovanni Gentile (University of Southern California, 1934).

- Patrick Romanell, The Philosophy of Giovanni Gentile (Columbia University, 1937).

- Patrick Romanell, Croce versus Gentile (S. F. Vanni, 1946).

- Roger W. Holmes, The Idealism of Giovanni Gentile (The Macmillan Company, 1937).

- Ugo Spirito, "The Religious Feeling of Giovanni Gentile," East and West, Vol. 5, No. 2 (July 1954).

- William A. Smith, Giovanni Gentile on the Existence of God (Beatrice-Naewolaerts, 1970).

- Valmai Burwood Evans, "The Ethics of Giovanni Gentile," International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 39, No. 2 (Jan. 1929).

- Valmai Burwood Evans, "Education in the Philosophy of Giovanni Gentile," International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Jan. 1933).

In Italian

- Giovanni Gentile (Augusto del Noce, Bologna: Il Mulino, 1990)

- Giovanni Gentile filosofo europeo (Salvatore Natoli, Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1989)

- Giovanni Gentile (Antimo Negri, Florence: La Nuova Italia, 1975)

- Faremo una grande università: Girolamo Palazzina-Giovanni Gentile; Un epistolario (1930–1938), a cura di Marzio Achille Romano (Milano: Edizioni Giuridiche Economiche Aziendali dell'Università Bocconi e Giuffré editori S.p.A., 1999)

- Parlato, Giuseppe. "Giovanni Gentile: From the Risorgimento to Fascism." Trans. Stefano Maranzana. TELOS 133 (Winter 2005): pp. 75–94.

- Antonio Cammarana, Proposizioni sulla filosofia di Giovanni Gentile, prefazione del Sen. Armando Plebe, Roma, Gruppo parliamentare MSI-DN, Senato della Repubblica, 1975, 157 Pagine, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze BN 758951.

- Antonio Cammarana, Teorica della reazione dialettica : filosofia del postcomunismo, Roma, Gruppo parliamentare MSI-DN, Senato della Repubblica, 1976, 109 Pagine, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze BN 775492.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giovanni Gentile. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Giovanni Gentile |

- Castelvetrano website

- Works by Giovanni Gentile at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Giovanni Gentile at Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Giovanni Gentile in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW