Oscan language

Oscan is an extinct Indo-European language of southern Italy. The language is also the namesake of the language group to which it belonged. As a member of the Italic languages, Oscan is therefore a sister language to Latin and Umbrian.

| Oscan | |

|---|---|

Denarius of Marsican Confederation with Oscan legend | |

| Native to | Samnium, Campania, Lucania, Calabria and Abruzzo |

| Region | south and south-central Italy |

| Extinct | >79 CE[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Old Italic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | osc |

osc | |

| Glottolog | osca1244[2] |

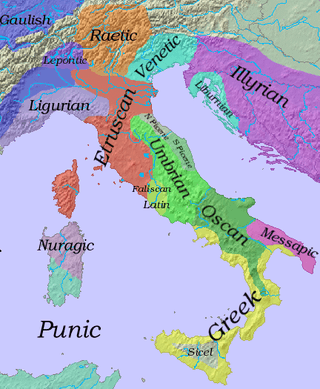

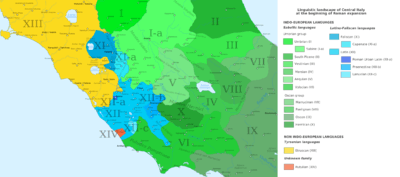

Approximate distribution of languages in Iron Age Italy in the sixth century BCE | |

Oscan was spoken by a number of tribes, including the Samnites,[3] the Aurunci (Ausones), and the Sidicini. The latter two tribes were often grouped under the name "Osci". The Oscan group is part of the Osco-Umbrian or Sabellic family, and includes the Oscan language and three variants (Hernican, Marrucinian and Paelignian) known only from inscriptions left by the Hernici, Marrucini and Paeligni, minor tribes of eastern central Italy. The language was spoken until approximately CE 100.[4]

Evidence

Oscan is known from inscriptions dating as far back as the 5th century BCE. The most important Oscan inscriptions are the Tabula Bantina, the Oscan Tablet or Tabula Osca[5], and the Cippus Abellanus. In Apulia, Oscan are also the legends of the ancient currencies (dating back to before 300 BC)[6] found at Teanum Apulum.[7] Oscan graffiti on the walls of Pompeii indicate its persistence in at least one urban environment well into the 1st century of the common era.[8]

In total, as of 2017, there were 800 Oscan texts, with a rapid expansion in recent decades.[9] Oscan was written in various scripts depending on time period and location, including the "native" Oscan script, the South Oscan script which was based on Greek, and the ultimately prevailing Roman Oscan script.[9]

Demise

In coastal zones of Southern Italy, Oscan is thought to have survived 3 centuries of bilingualism with Greek between 400 and 100 BCE, making it "an unusual case of stable societal bilingualism" wherein neither language became dominant or caused the death of the other; however, over the course of the Roman period both Oscan and Greek would be progressively effaced from Southern Italy, excepting the controversial possibility of Griko representing a continuation of ancient dialects of Greek.[9]

Oscan was likely banned from official usage after 80 BCE.[1] Its usage declined following the Social War.[10] However, graffiti in towns across the Oscan speech area indicate it remained in good health after this.[1] A very strong piece of evidence is the presence of Oscan graffiti on walls of Pompeii that were reconstructed after the earthquake of CE 62,[11][12] and must therefore have been written between CE 62 and 79.[1]

General characteristics

Oscan had much in common with Latin, though there are also many striking differences, and many common word-groups in Latin were absent or represented by entirely different forms. For example, Latin volo, velle, volui, and other such forms from the Proto-Indo-European root *wel ('to will') were represented by words derived from *gher ('to desire'): Oscan herest ('(s)he shall want, (s)he shall desire', English cognate 'yearn') as opposed to Latin vult (id.). Latin locus (place) was absent and represented by the hapax slaagid (place), which Italian linguist Alberto Manco has linked to a surviving local toponym.[13]

In phonology too, Oscan exhibited a number of clear differences from Latin: thus, Oscan 'p' in place of Latin 'qu' (Osc. pis, Lat. quis) (compare the similar P-Celtic/Q-Celtic cleavage in the Celtic languages); 'b' in place of Latin 'v'; medial 'f' in contrast to Latin 'b' or 'd' (Osc. mefiai, Lat. mediae).[14]

Oscan is considered to be the most conservative of all the known Italic languages, and among attested Indo-European languages it is rivaled only by Greek in the retention of the inherited vowel system with the diphthongs intact.[15]

Writing system

Alphabet

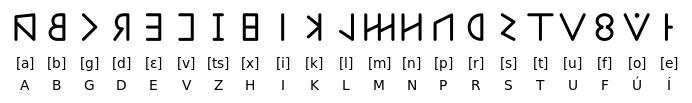

Oscan was originally written in a specific "Oscan alphabet", one of the Old Italic scripts derived from (or cognate with) the Etruscan alphabet. Later inscriptions are written in the Greek and Latin alphabets.[16]

The "Etruscan" alphabet

The Osci probably adopted the archaic Etruscan alphabet during the 7th century BCE, but a recognizably Oscan variant of the alphabet is attested only from the 5th century BCE; its sign inventory extended over the classical Etruscan alphabet by the introduction of lowered variants of I and U, transcribed as Í and Ú. Ú came to be used to represent Oscan /o/, while U was used for /u/ as well as historical long */oː/, which had undergone a sound shift in Oscan to become ~[uː].

The Z of the native alphabet is pronounced [ts].[17] The letters Ú and Í are "differentiations" of U and I, and do not appear in the oldest writings.[17] The Ú represents an o-sound,[14] and Í is a higher-mid [ẹ]. Doubling of vowels was used to denote length but a long I is written IÍ.[17]

The "Greek" alphabet

Oscan written with the Greek alphabet was identical to the standard alphabet with the addition of two letters: one for the native alphabet's H and one for its V.[14] The letters η and ω do not indicate quantity.[14] Sometimes, the clusters ηι and ωϝ denote the diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/ respectively while ει and oυ are saved to denote monophthongs /iː/ and /uː/ of the native alphabet.[14] At other times, ει and oυ are used to denote diphthongs, in which case o denotes the /uː/ sound.[14]

The "Latin" alphabet

When written in the Latin alphabet, the Oscan Z does not represent [ts] but instead [z], which is not written differently from [s] in the native alphabet.[16]

History of sounds

Vowels

Vowels are regularly lengthened before ns and nct (in the latter of which the n is lost) and possibly before nf and nx as well.[18] Anaptyxis, the development of a vowel between a liquid or nasal and another consonant, preceding or following, occurs frequently in Oscan; if the other consonant precedes, the new vowel is the same as that of the preceding vowel. If the other consonant follows, the new vowel is the same as that of the following vowel.[19]

Monophthongs

A

Short a remains in most positions.[20] Long ā remains in an initial or medial position. Final ā starts to sound similar to [ɔː] so that it is written ú or, rarely, u.[21]

E

Short e "generally remains unchanged;" before a labial in a medial syllable, it becomes u or i and before another vowel, e becomes í.[22] Long ē becomes the sound of í or íí.[23]

I

Short i becomes written í.[24] Long ī is spelt with i but when written with doubling as a mark of length with ií.[25]

O

Short o remains mostly unchanged, written ú;[26] before a final -m, o becomes more like u.[27] Long ō becomes denoted by u or uu.[28]

U

Short u generally remains unchanged; after t, d, n, the sound becomes that of iu.[29] Long ū generally remains unchanged; it may have changed to an ī sound for final syllables.[30]

Diphthongs

The sounds of diphthongs remain unchanged.[15]

Consonants

S

In Oscan, S between vowels did not undergo rhotacism as it did in Latin; but it was voiced, becoming the sound /z/. However, between vowels, the original cluster rs developed either to a simple r with lengthening on the preceding vowel, or to a long rr (as in Latin), and at the end of a word, original rs becomes r just as in Latin. Unlike in Latin, the s is not dropped from the consonant clusters sm, sn, sl.[31]

Example of an Oscan text

Taken from the Cippus Abellanus

ekkum svaí píd herieset

trííbarak avúm tereí púd liímítúm pernúm púís herekleís fíísnú mefiíst, ú ehtrad feíhúss pús herekleís fíísnam amfr et, pert víam pússtíst paí íp íst, pústin slagím senateís suveís tangi núd tríbarakavúm lí kítud. íním íúk tríba rakkiuf pam núvlanús tríbarakattuset íúk trí barakkiuf íním úíttiuf abellanúm estud. avt púst feíhúís pús físnam am fret, eíseí tereí nep abel lanús nep núvlanús pídum tríbarakattíns. avt the savrúm púd eseí tereí íst, pún patensíns, múíníkad tan ginúd patensíns, íním píd eíseí thesavreí púkkapíd eestit aíttíúm alttram alttrús herríns. avt anter slagím abellanam íním núvlanam súllad víú uruvú íst . edú eísaí víaí mefiaí teremen niú staíet.

In Latin:

Item [si quid volent]

aedificare [in territorio quod limitibus tenus [quibus] Herculis fanum medium est, extra muros, qui Herculis fanum ambiunt, trans viam positum est, quae ibi est, pro finibus senatus sui sententia, aedificare liceto. Et id aedificium quod Nolani aedificaverint, et usus Nolanorum esto. Item si quid Abellani aedificaverint, id aedificium et usus Abellanorum esto. At post muros qui fanum ambi- unt, in eo territorio neque Avel- lani neque Nolani quidquam aedificaverint. At the- saurum qui in eo territorio est, cum aperirent, communi senten- tia aperirent, et quidquid in eo thesauro quandoque extat, caperent. At inter fines Abellanos et Nolanos ubique via felxa est –, in ea via media termina

stant.

See also

- Ancient peoples of Italy

References

- Schrijver, Peter. Oscan love of Rome. Page 2.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Oscan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Davide Monaco. "Samnites The People". Sanniti.info. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- "Oscan". Ancient Scripts. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- http://www.sanniti.info/smagnony.html

- "Teano Apulo". Treccani (in Italian).

- Salvemini Biagio, Massafra Angelo. Storia della Puglia. Dalle origini al Seicento (in Italian). Laterza.

- Freeman, Philip (1999). The Survival of Etruscan. Page 82: "Oscan graffiti on the walls of Pompeii show that non-Latin languages could thrive in urban locations in Italy well into the 1st century CE."

- McDonald, K. L. (2017). "Fragmentary ancient languages as “bad data”: towards a methodology for investigating multilingualism in epigraphic sources." Pages 4–6

- Lomas, Kathryn, "The Hellenization of Italy", in Powell, Anton. The Greek World. Page 354.

- Cooley, Alison (2002)."The survival of Oscan in Roman Pompeii", in A.E. Cooley (ed.), Becoming Roman, Writing Latin? Literacy and Epigraphy in the Roman West, Portsmouth (Journal of Roman Archaeology), 77–86. Page 84

- Cooley (2014). Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook. New York – London (Routledge). Page 104.

- Alberto Manco, "Sull’osco *slagi-", AIΩN Linguistica 28, 2006.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 7-8. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 29–30. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 1432691325.

- Buck, Carl Darling (2007) [1904]. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With A Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 73–76. ISBN 1432691325.

Sources

- Buck, Carl Darling (1904). A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian with a Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Internet Archive.

- Salvucci, Claudio R (1999). A Vocabulary of Oscan Including the Oscan and Samnite Glosses. Southampton, Pennsylvania: Evolution Publishing and Manufacturing Co.

Further reading

- Buck, Carl Darling. 1979. A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian: With a Collection of Inscriptions and a Glossary. Hildesheim: Olms.

- Decorte, Robrecht. 2016. "Sine dolo malo: The Influence and Impact of Latin Legalese on the Oscan Law of the Tabula Bantina". Mnemosyne 69 (2): 276–91.

- Lejeune, Michel. "Phonologie osque et graphie grecque". In: Revue des Études Anciennes. Tome 72, 1970, n°3-4. pp. 271-316. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/rea.1970.3871] ; [www.persee.fr/doc/rea_0035-2004_1970_num_72_3_3871]

- McDonald, Katherine. 2015. Oscan in Southern Italy and Sicily: Evaluating Language Contact in a Fragmentary Corpus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salvucci, Claudio R. 1999. A Vocabulary of Oscan: Including the Oscan and Samnite Glosses. Southampton, PA: Evolution Publishing.

- Schrijver, Peter. 2016. "Oscan Love of Rome". Glotta 92 (1): 223–26.

- Zair, Nicholas. 2016. Oscan in the Greek Alphabet. New York: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Library resources about Oscan language |

- Hare, JB (2005). "Oscan". wordgumbo. Retrieved 21 August 2010.