Marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated, although there are exceptions. In geology, the term marble refers to metamorphosed limestone, but its use in stonemasonry more broadly encompasses unmetamorphosed limestone.[1] Marble is commonly used for sculpture and as a building material.

Etymology

The word "marble" derives from the Ancient Greek μάρμαρον (mármaron),[2] from μάρμαρος (mármaros), "crystalline rock, shining stone",[3][4] perhaps from the verb μαρμαίρω (marmaírō), "to flash, sparkle, gleam";[5] R. S. P. Beekes has suggested that a "Pre-Greek origin is probable".[6]

This stem is also the ancestor of the English word "marmoreal", meaning "marble-like."[7] While the English term "marble" resembles the French marbre, most other European languages (with words like "marmoreal") more closely resemble the original Ancient Greek.

Physical origins

Marble is a rock resulting from metamorphism of sedimentary carbonate rocks, most commonly limestone or dolomite rock. Metamorphism causes variable recrystallization of the original carbonate mineral grains. The resulting marble rock is typically composed of an interlocking mosaic of carbonate crystals. Primary sedimentary textures and structures of the original carbonate rock (protolith) have typically been modified or destroyed.

Pure white marble is the result of metamorphism of a very pure (silicate-poor) limestone or dolomite protolith. The characteristic swirls and veins of many colored marble varieties are usually due to various mineral impurities such as clay, silt, sand, iron oxides, or chert which were originally present as grains or layers in the limestone. Green coloration is often due to serpentine resulting from originally magnesium-rich limestone or dolomite with silica impurities. These various impurities have been mobilized and recrystallized by the intense pressure and heat of the metamorphism.

Types

Examples of historically notable marble varieties and locations:

Uses

Sculpture

White marble has been prized for its use in sculptures[10] since classical times. This preference has to do with its softness, which made it easier to carve, relative isotropy and homogeneity, and a relative resistance to shattering. Also, the low index of refraction of calcite allows light to penetrate several millimeters into the stone before being scattered out, resulting in the characteristic waxy look which brings a lifelike luster to marble sculptures of any kind, which is why many sculptors preferred and still prefer marble for sculpting.

Construction marble

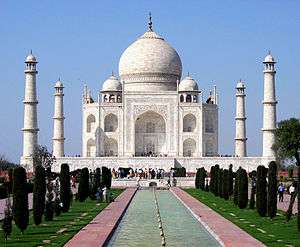

Construction marble is a stone which is composed of calcite, dolomite or serpentine that is capable of taking a polish.[11] More generally in construction, specifically the dimension stone trade, the term marble is used for any crystalline calcitic rock (and some non-calcitic rocks) useful as building stone. For example, Tennessee marble is really a dense granular fossiliferous gray to pink to maroon Ordovician limestone, that geologists call the Holston Formation.

Ashgabat, the capital city of Turkmenistan, was recorded in the 2013 Guinness Book of Records as having the world's highest concentration of white marble buildings.[12]

Production

.jpg)

22°06′16″S 015°48′48″E

According to the United States Geological Survey, U.S. domestic marble production in 2006 was 46,400 tons valued at about $18.1 million, compared to 72,300 tons valued at $18.9 million in 2005. Crushed marble production (for aggregate and industrial uses) in 2006 was 11.8 million tons valued at $116 million, of which 6.5 million tons was finely ground calcium carbonate and the rest was construction aggregate. For comparison, 2005 crushed marble production was 7.76 million tons valued at $58.7 million, of which 4.8 million tons was finely ground calcium carbonate and the rest was construction aggregate. U.S. dimension marble demand is about 1.3 million tons. The DSAN World Demand for (finished) Marble Index has shown a growth of 12% annually for the 2000–2006 period, compared to 10.5% annually for the 2000–2005 period. The largest dimension marble application is tile.

In 1998, marble production was dominated by 4 countries that accounted for almost half of world production of marble and decorative stone. Italy and China were the world leaders, each representing 16% of world production, while Spain and India produced 9% and 8%, respectively.[13]

In 2018 Turkey was the world leader in marble export, with 42% share in global marble trade, followed by Italy with 18% and Greece with 10%. The largest importer of marble in 2018 was China with a 64% market share, followed by India with 11% and Italy with 5%.[14]

Occupational safety

Dust produced by cutting marble could cause lung disease but more research needs to be carried out on whether dust filters and other safety products reduce this risk.[15]

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for marble exposure in the workplace as 15 mg/m3 total exposure and 5 mg/m3 respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 10 mg/m3 total exposure and 5 mg/m3 respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday.[16]

Degradation by acids

Acids damage marble, because the calcium carbonate in marble reacts with them, releasing carbon dioxide (technically speaking, carbonic acid, but that decomposes quickly to CO2 and H2O) :

- CaCO3(s) + 2H+(aq) → Ca2+(aq) + CO2(g) + H2O (l)

Thus, vinegar or other acidic solutions should never be used on marble. Likewise, outdoor marble statues, gravestones, or other marble structures are damaged by acid rain.

Microbial degradation

The haloalkaliphilic methylotrophic bacterium Methylophaga murata was isolated from deteriorating marble in the Kremlin.[17] Bacterial and fungal degradation was detected in four samples of marble from Milan cathedral; black Cladosporium attacked dried acrylic resin[18] using melanin.[19]

Cultural associations

As the favorite medium for Greek and Roman sculptors and architects (see classical sculpture), marble has become a cultural symbol of tradition and refined taste. Its extremely varied and colorful patterns make it a favorite decorative material, and it is often imitated in background patterns for computer displays, etc.

Places named after the stone include Marblehead, Massachusetts; Marblehead, Ohio; Marble Arch, London; the Sea of Marmara; India's Marble Rocks; and the towns of Marble, Minnesota; Marble, Colorado; Marble Falls, Texas, and Marble Hill, Manhattan, New York. The Elgin Marbles are marble sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens that are on display in the British Museum. They were brought to Britain by the Earl of Elgin.

Artificial marble

Marble dust is combined with cement or synthetic resins to make reconstituted or cultured marble. The appearance of marble can be simulated with faux marbling, a painting technique that imitates the stone's color patterns.

Gallery

The Nike of Samothrace is made of Parian marble (c. 220–190 BC)

The Nike of Samothrace is made of Parian marble (c. 220–190 BC) Laocoön and His Sons in the Vatican

Laocoön and His Sons in the Vatican- The Praetorians Relief, made from grey veined marble, c. 51–52 AD

Cleopatra by William Wetmore Story was described and admired in Nathaniel Hawthorne's romance, The Marble Faun, and is on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Cleopatra by William Wetmore Story was described and admired in Nathaniel Hawthorne's romance, The Marble Faun, and is on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Näckrosen (Water Lily), Stockholm 1892, by Swedish sculptor Per Hasselberg (1850-1894). Here a copy from 1953 in marble by Giovanni Ardini (Italy) placed in Rottneros Park near Sunne in Värmland/Sweden.

Näckrosen (Water Lily), Stockholm 1892, by Swedish sculptor Per Hasselberg (1850-1894). Here a copy from 1953 in marble by Giovanni Ardini (Italy) placed in Rottneros Park near Sunne in Värmland/Sweden. Pažaislis Monastery complex has the most marble-decorated Baroque church of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Pažaislis Monastery complex has the most marble-decorated Baroque church of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

See also

- Marble sculpture

- Paper marbling

- Marmorino

- Pietra dura, inlaying with marble and other stones

- Scagliola, imitating marble with plasterwork

- Verd antique, sometimes (erroneously) called "serpentine marble", and also known as Connemara marble

- Ruin marble, marble that contains light and dark patterns, giving the impression of a ruined cityscape

References

- Kearey, Philip (2001). Dictionary of Geology, Penguin Group, London and New York, p. 163. ISBN 978-0-14-051494-0

- μάρμαρον, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- μάρμαρος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- Marble, Compact Oxford English Dictionary. Askoxford.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-30.

- μαρμαίρω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 907.

- "Definition of MARMOREAL". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Pentelic marble, Britannica Online Encyclopaedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-30.

- "RAPORT DE ȚARĂ. Domul din Milano a fost reconstruit cu marmură de Rușchița". Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- PROCEEDINGS 4th International Congress on "Science and Technology for the Safeguard of Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean Basin" VOL. I. Angelo Ferrari. p. 371. ISBN 9788896680315.

white marble prized for use to make sculptures.

- Marble Institute of America pp. 223 Glossary

- "Turkmenistan enters record books for having the most white marble buildings | World news". theguardian.com. London. 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Strategic positioning study of the marble branch. CEPI Brief N° 6. tunisianindustry.nat.tn

- Comtrade. "Comtrade Explorer - Snapshot HS 2515 (Marble, travertine, ecaussine and other stone)". United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Foja, A.F. (1993) Marble industry: its socioeconomic, environmental and health effects among marble worker/producer households in Romblon. Philippines University Thesis. fao.org

- "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Marble". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- Doronina NV; Li TsD; Ivanova EG; Trotsenko IuA. (2005). "Methylophaga murata sp. nov.: a haloalkaliphilic aerobic methylotroph from deteriorating marble". Mikrobiologiia. 74 (4): 511–9. PMID 16211855.

- Cappitelli F; Principi P; Pedrazzani R; Toniolo L; Sorlini C (2007). "Bacterial and fungal deterioration of the Milan Cathedral marble treated with protective synthetic resins". Science of the Total Environment. 385 (1–3): 172–81. Bibcode:2007ScTEn.385..172C. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.06.022. PMID 17658586.

- Cappitelli F; Nosanchuk JD; Casadevall A; Toniolo L; Brusetti L; Florio S; Principi P; Borin S; Sorlini C (Jan 2007). "Synthetic consolidants attacked by melanin-producing fungi: case study of the biodeterioration of Milan (Italy) cathedral marble treated with acrylics". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 73 (1): 271–7. doi:10.1128/AEM.02220-06. PMC 1797126. PMID 17071788.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marble. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Marble. |

- Dimension Stone Statistics and Information – United States Geological Survey minerals information for dimension stone

- USGS 2005 Minerals Yearbook: Stone, Crushed

- USGS 2005 Minerals Yearbook: Stone, Dimension

- USGS 2006 Minerals Yearbook: Stone, Crushed

- USGS 2006 Minerals Yearbook: Stone, Dimension

- Marble Institute of America