Australia

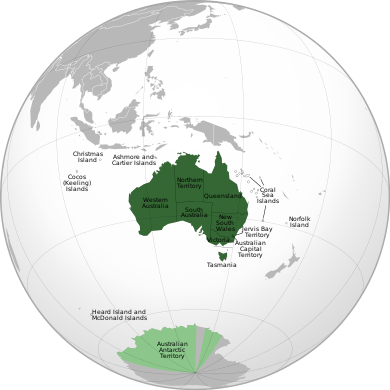

Australia, officially known as the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands.[12] It is the largest country in Oceania and the world's sixth-largest country by total area. The population of 26 million[6] is highly urbanised and heavily concentrated on the eastern seaboard.[13] Australia's capital is Canberra, and its largest city is Sydney. The country's other major metropolitan areas are Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide.

Commonwealth of Australia | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Commonwealth of Australia, including the Australian territorial claim in the Antarctic | |

| Capital | Canberra 35°18′29″S 149°07′28″E |

| Largest city | Sydney |

| National language | English[N 2] |

| Religion (2016)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| David Hurley | |

| Scott Morrison | |

| Michael McCormack | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 1 January 1901 | |

| 9 October 1942 (with effect from 3 September 1939) | |

| 3 March 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 7,692,024 km2 (2,969,907 sq mi) (6th) |

• Water (%) | 0.76 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 25,647,700[6] (54th) |

• 2016 census | 23,401,892[7] |

• Density | 3.3/km2 (8.5/sq mi) (192nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | 34.0[9] medium · 22nd |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 6th |

| Currency | Australian dollar (AUD) |

| Time zone | UTC+8; +9.5; +10 (Various[N 4]) |

| UTC+8; +9.5; +10; +10.5; +11 (Various[N 4]) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy yyyy-mm-dd[11] |

| Mains electricity | 230 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +61 |

| ISO 3166 code | AU |

| Internet TLD | .au |

Indigenous Australians inhabited the continent for about 65,000 years[14] prior to the first arrival of Dutch explorers in the early 17th century, who named it New Holland. In 1770, Australia's eastern half was claimed by Great Britain and initially settled through penal transportation to the colony of New South Wales from 26 January 1788, a date which became Australia's national day. The population grew steadily in subsequent decades, and by the time of an 1850s gold rush, most of the continent had been explored by European settlers and an additional five self-governing crown colonies established. On 1 January 1901, the six colonies federated, forming the Commonwealth of Australia. Australia has since maintained a stable liberal democratic political system that functions as a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy, comprising six states and ten territories.

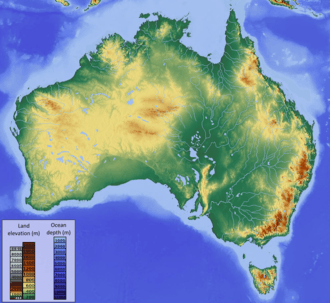

Australia is the oldest,[15] flattest,[16] and driest inhabited continent,[17][18] with the least fertile soils.[19][20] It has a landmass of 7,617,930 square kilometres (2,941,300 sq mi).[21] A megadiverse country, its size gives it a wide variety of landscapes, with deserts in the centre, tropical rainforests in the north-east, and mountain ranges in the south-east. Australia generates its income from various sources, including mining-related exports, telecommunications, banking, manufacturing, and international education.[22][23][24]

Australia is a highly developed country, with the world's 14th-largest economy. It has a high-income economy, with the world's tenth-highest per capita income.[25] It is a regional power and has the world's 13th-highest military expenditure.[26] Immigrants account for 30% of the population,[27] the highest proportion in any country with a population over 10 million.[28] Having the third-highest human development index and the eighth-highest ranked democracy globally, the country ranks highly in quality of life, health, education, economic freedom, civil liberties, and political rights,[29] with all its major cities faring well in global comparative livability surveys.[30] Australia is a member of the United Nations, G20, Commonwealth of Nations, ANZUS, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Trade Organization, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Pacific Islands Forum, and the ASEAN Plus Six mechanism.

Name

The name Australia (pronounced /əˈstreɪliə/ in Australian English[31]) is derived from the Latin Terra Australis ("southern land"), a name used for a hypothetical continent in the Southern Hemisphere since ancient times.[32] When Europeans first began visiting and mapping Australia in the 17th century, the name Terra Australis was naturally applied to the new territories.[N 5]

Until the early 19th century, Australia was best known as "New Holland", a name first applied by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1644 (as Nieuw-Holland) and subsequently anglicised. Terra Australis still saw occasional usage, such as in scientific texts.[N 6] The name Australia was popularised by the explorer Matthew Flinders, who said it was "more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth".[38] Several famous early cartographers also made use of the word Australia on maps. Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) used the phrase climata australia on his double cordiform map of the world of 1538, as did Gemma Frisius (1508–1555), who was Mercator's teacher and collaborator, on his own cordiform wall map in 1540. Australia appears in a book on astronomy by Cyriaco Jacob zum Barth published in Frankfurt-am-Main in 1545.[39]

The first time that Australia appears to have been officially used was in April 1817, when Governor Lachlan Macquarie acknowledged the receipt of Flinders' charts of Australia from Lord Bathurst.[40] In December 1817, Macquarie recommended to the Colonial Office that it be formally adopted.[41] In 1824, the Admiralty agreed that the continent should be known officially by that name.[42] The first official published use of the new name came with the publication in 1830 of The Australia Directory by the Hydrographic Office.[43]

Colloquial names for Australia include "Oz" and "the Land Down Under" (usually shortened to just "Down Under"). Other epithets include "the Great Southern Land", "the Lucky Country", "the Sunburnt Country", and "the Wide Brown Land". The latter two both derive from Dorothea Mackellar's 1908 poem "My Country".[44]

History

Prehistory

Human habitation of the Australian continent is known to have begun at least 65,000 years ago,[45][46] with the migration of people by land bridges and short sea-crossings from what is now Southeast Asia.[47] The Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem Land is recognised as the oldest site showing the presence of humans in Australia.[48] The oldest human remains found are the Lake Mungo remains, which have been dated to around 41,000 years ago.[49][50] These people were the ancestors of modern Indigenous Australians.[51] Aboriginal Australian culture is one of the oldest continual cultures on earth.[52]

At the time of first European contact, most Indigenous Australians were hunter-gatherers with complex economies and societies.[53][54] Recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 750,000 could have been sustained.[55][56] Indigenous Australians have an oral culture with spiritual values based on reverence for the land and a belief in the Dreamtime.[57] The Torres Strait Islanders, ethnically Melanesian, obtained their livelihood from seasonal horticulture and the resources of their reefs and seas.[58] The northern coasts and waters of Australia were visited sporadically by Makassan fishermen from what is now Indonesia.[59]

European arrival

The first recorded European sighting of the Australian mainland, and the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent, are attributed to the Dutch.[60] The first ship and crew to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people was the Duyfken captained by Dutch navigator, Willem Janszoon.[61] He sighted the coast of Cape York Peninsula in early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February at the Pennefather River near the modern town of Weipa on Cape York.[62] Later that year, Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through, and navigated, Torres Strait islands.[63] The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent "New Holland" during the 17th century, and although no attempt at settlement was made,[62] a number of shipwrecks left men either stranded or, as in the case of the Batavia in 1629, marooned for mutiny and murder, thus becoming the first Europeans to permanently inhabit the continent.[64] William Dampier, an English explorer and privateer, landed on the north-west coast of New Holland in 1688 (while serving as a crewman under pirate Captain John Read[65]) and again in 1699 on a return trip.[66] In 1770, James Cook sailed along and mapped the east coast, which he named New South Wales and claimed for Great Britain.[67]

With the loss of its American colonies in 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, the "First Fleet", under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, to establish a new penal colony in New South Wales. A camp was set up and the Union flag raised at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, on 26 January 1788,[68][69] a date which later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. Most early convicts were transported for petty crimes and assigned as labourers or servants upon arrival. While the majority settled into colonial society once emancipated, convict rebellions and uprisings were also staged, but invariably suppressed under martial law. The 1808 Rum Rebellion, the only successful armed takeover of government in Australia, instigated a two-year period of military rule.[70]

The indigenous population declined for 150 years following settlement, mainly due to infectious disease.[71] Thousands more died as a result of frontier conflict with settlers.[72] A government policy of "assimilation" beginning with the Aboriginal Protection Act 1869 resulted in the removal of many Aboriginal children from their families and communities—referred to as the Stolen Generations—a practice which also contributed to the decline in the indigenous population.[73] As a result of the 1967 referendum, the Federal government's power to enact special laws with respect to a particular race was extended to enable the making of laws with respect to Aboriginals.[74] Traditional ownership of land ("native title") was not recognised in law until 1992, when the High Court of Australia held in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) that the legal doctrine that Australia had been terra nullius ("land belonging to no one") did not apply to Australia at the time of British settlement.[75]

Colonial expansion

The expansion of British control over other areas of the continent began in the early 19th century, initially confined to coastal regions. A settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) in 1803, and it became a separate colony in 1825.[76] In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson and William Wentworth crossed the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, opening the interior to European settlement.[77] The British claim was extended to the whole Australian continent in 1827 when Major Edmund Lockyer established a settlement on King George Sound (modern-day Albany, Western Australia).[78] The Swan River Colony was established in 1829, evolving into the largest Australian colony by area, Western Australia.[79] In accordance with population growth, separate colonies were carved from parts of New South Wales: South Australia in 1836, New Zealand in 1841, Victoria in 1851, and Queensland in 1859.[80] The Northern Territory was excised from South Australia in 1911.[81] South Australia was founded as a "free province"—it was never a penal colony.[82] Western Australia was also founded "free" but later accepted transported convicts, the last of which arrived in 1868, decades after transportation had ceased to the other colonies.[83] By 1850, Europeans still had not entered large areas of the inland. Explorers remained ambitious to discover new lands for agriculture or answers to scientific enquiries.[84]

A series of gold rushes beginning in the early 1850s led to an influx of new migrants from China, North America and mainland Europe,[85] and also spurred outbreaks of bushranging and civil unrest. The latter peaked in 1854 when Ballarat miners launched the Eureka Rebellion against gold license fees.[86] Between 1855 and 1890, the six colonies individually gained responsible government, managing most of their own affairs while remaining part of the British Empire.[87] The Colonial Office in London retained control of some matters, notably foreign affairs,[88] defence,[89] and international shipping.

Nationhood

On 1 January 1901, federation of the colonies was achieved after a decade of planning, consultation and voting.[90] After the 1907 Imperial Conference, Australia and the other self-governing British colonies were given the status of "dominion" within the British Empire.[91][92] The Federal Capital Territory (later renamed the Australian Capital Territory) was formed in 1911 as the location for the future federal capital of Canberra. Melbourne was the temporary seat of government from 1901 to 1927 while Canberra was being constructed.[93] The Northern Territory was transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the federal parliament in 1911.[94] Australia became the colonial ruler of the Territory of Papua (which had initially been annexed by Queensland in 1888) in 1902 and of the Territory of New Guinea (formerly German New Guinea) in 1920. The two were unified as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea in 1949 and gained independence from Australia in 1975.

In 1914, Australia joined Britain in fighting World War I, with support from both the outgoing Commonwealth Liberal Party and the incoming Australian Labor Party.[95][96] Australians took part in many of the major battles fought on the Western Front.[97] Of about 416,000 who served, about 60,000 were killed and another 152,000 were wounded.[98] Many Australians regard the defeat of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) at Gallipoli as the birth of the nation—its first major military action.[99][100] The Kokoda Track campaign is regarded by many as an analogous nation-defining event during World War II.[101]

Britain's Statute of Westminster 1931 formally ended most of the constitutional links between Australia and the UK. Australia adopted it in 1942,[102] but it was backdated to 1939 to confirm the validity of legislation passed by the Australian Parliament during World War II.[103][104] The shock of Britain's defeat in Asia in 1942, followed soon after by the Japanese bombing of Darwin and attack on Sydney Harbour, led to a widespread belief in Australia that an invasion was imminent, and a shift towards the United States as a new ally and protector.[105] Since 1951, Australia has been a formal military ally of the US, under the ANZUS treaty.[106]

After World War II, Australia encouraged immigration from mainland Europe. Since the 1970s and following the abolition of the White Australia policy, immigration from Asia and elsewhere was also promoted.[107] As a result, Australia's demography, culture, and self-image were transformed.[108] The Australia Act 1986 severed the remaining constitutional ties between Australia and the UK.[109] In a 1999 referendum, 55% of voters and a majority in every state rejected a proposal to become a republic with a president appointed by a two-thirds vote in both Houses of the Australian Parliament. There has been an increasing focus in foreign policy on ties with other Pacific Rim nations, while maintaining close ties with Australia's traditional allies and trading partners.[110]

Geography and environment

General characteristics

Surrounded by the Indian and Pacific oceans,[N 7] Australia is separated from Asia by the Arafura and Timor seas, with the Coral Sea lying off the Queensland coast, and the Tasman Sea lying between Australia and New Zealand. The world's smallest continent[112] and sixth largest country by total area,[113] Australia—owing to its size and isolation—is often dubbed the "island continent"[114] and is sometimes considered the world's largest island.[115] Australia has 34,218 kilometres (21,262 mi) of coastline (excluding all offshore islands),[116] and claims an extensive Exclusive Economic Zone of 8,148,250 square kilometres (3,146,060 sq mi). This exclusive economic zone does not include the Australian Antarctic Territory.[117] Apart from Macquarie Island, Australia lies between latitudes 9° and 44°S, and longitudes 112° and 154°E.

Australia's size gives it a wide variety of landscapes, with tropical rainforests in the north-east, mountain ranges in the south-east, south-west and east, and desert in the centre.[118] The desert or semi-arid land commonly known as the outback makes up by far the largest portion of land.[119] Australia is the driest inhabited continent; its annual rainfall averaged over continental area is less than 500 mm.[120] The population density is 3.2 inhabitants per square kilometre, although a large proportion of the population lives along the temperate south-eastern coastline.[121]

The Great Barrier Reef, the world's largest coral reef,[122] lies a short distance off the north-east coast and extends for over 2,000 kilometres (1,240 mi). Mount Augustus, claimed to be the world's largest monolith,[123] is located in Western Australia. At 2,228 metres (7,310 ft), Mount Kosciuszko is the highest mountain on the Australian mainland. Even taller are Mawson Peak (at 2,745 metres or 9,006 feet), on the remote Australian external territory of Heard Island, and, in the Australian Antarctic Territory, Mount McClintock and Mount Menzies, at 3,492 metres (11,457 ft) and 3,355 metres (11,007 ft) respectively.[124]

Eastern Australia is marked by the Great Dividing Range, which runs parallel to the coast of Queensland, New South Wales and much of Victoria. The name is not strictly accurate, because parts of the range consist of low hills, and the highlands are typically no more than 1,600 metres (5,249 ft) in height.[125] The coastal uplands and a belt of Brigalow grasslands lie between the coast and the mountains, while inland of the dividing range are large areas of grassland and shrubland.[125][126] These include the western plains of New South Wales, and the Mitchell Grass Downs and Mulga Lands of inland Queensland. The northernmost point of the east coast is the tropical Cape York Peninsula.[127][128][129][130]

The landscapes of the Top End and the Gulf Country—with their tropical climate—include forest, woodland, wetland, grassland, rainforest and desert.[131][132][133] At the north-west corner of the continent are the sandstone cliffs and gorges of The Kimberley, and below that the Pilbara. The Victoria Plains tropical savanna lies south of the Kimberly and Arnhem Land savannas, forming a transition between the coastal savannas and the interior deserts.[134][135][136] At the heart of the country are the uplands of central Australia. Prominent features of the centre and south include Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock), the famous sandstone monolith, and the inland Simpson, Tirari and Sturt Stony, Gibson, Great Sandy, Tanami, and Great Victoria deserts, with the famous Nullarbor Plain on the southern coast.[137][138][139][140] The Western Australian mulga shrublands lie between the interior deserts and Mediterranean-climate Southwest Australia.[141][142]

Geology

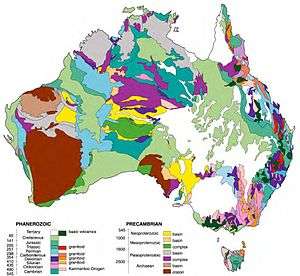

Lying on the Indo-Australian Plate, the mainland of Australia is the lowest and most primordial landmass on Earth with a relatively stable geological history.[143][144] The landmass includes virtually all known rock types and from all geological time periods spanning over 3.8 billion years of the Earth's history. The Pilbara Craton is one of only two pristine Archaean 3.6–2.7 Ga (billion years ago) crusts identified on the Earth.[145]

Having been part of all major supercontinents, the Australian continent began to form after the breakup of Gondwana in the Permian, with the separation of the continental landmass from the African continent and Indian subcontinent. It separated from Antarctica over a prolonged period beginning in the Permian and continuing through to the Cretaceous.[146] When the last glacial period ended in about 10,000 BC, rising sea levels formed Bass Strait, separating Tasmania from the mainland. Then between about 8,000 and 6,500 BC, the lowlands in the north were flooded by the sea, separating New Guinea, the Aru Islands, and the mainland of Australia.[147] The Australian continent is moving toward Eurasia at the rate of 6 to 7 centimetres a year.[148]

The Australian mainland's continental crust, excluding the thinned margins, has an average thickness of 38 km, with a range in thickness from 24 km to 59 km.[149] Australia's geology can be divided into several main sections, showcasing that the continent grew from west to east: the Archaean cratonic shields found mostly in the west, Proterozoic fold belts in the centre and Phanerozoic sedimentary basins, metamorphic and igneous rocks in the east.[150]

The Australian mainland and Tasmania are situated in the middle of the tectonic plate and have no active volcanoes,[151] but due to passing over the East Australia hotspot, recent volcanism has occurred during the Holocene, in the Newer Volcanics Province of western Victoria and southeastern South Australia. Volcanism also occurs in the island of New Guinea (considered geologically as part of the Australian continent), and in the Australian external territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands.[152] Seismic activity in the Australian mainland and Tasmania is also low, with the greatest number of fatalities having occurred in the 1989 Newcastle earthquake.[153]

Climate

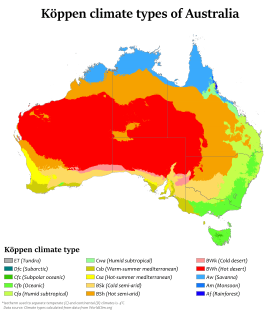

The climate of Australia is significantly influenced by ocean currents, including the Indian Ocean Dipole and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, which is correlated with periodic drought, and the seasonal tropical low-pressure system that produces cyclones in northern Australia.[155][156] These factors cause rainfall to vary markedly from year to year. Much of the northern part of the country has a tropical, predominantly summer-rainfall (monsoon).[120] The south-west corner of the country has a Mediterranean climate.[157] The south-east ranges from oceanic (Tasmania and coastal Victoria) to humid subtropical (upper half of New South Wales), with the highlands featuring alpine and subpolar oceanic climates. The interior is arid to semi-arid.[120]

According to the Bureau of Meteorology's 2011 Australian Climate Statement, Australia had lower than average temperatures in 2011 as a consequence of a La Niña weather pattern; however, "the country's 10-year average continues to demonstrate the rising trend in temperatures, with 2002–2011 likely to rank in the top two warmest 10-year periods on record for Australia, at 0.52 °C (0.94 °F) above the long-term average".[158] Furthermore, 2014 was Australia's third warmest year since national temperature observations commenced in 1910.[159][160]

Water restrictions are frequently in place in many regions and cities of Australia in response to chronic shortages due to urban population increases and localised drought.[161][162] Throughout much of the continent, major flooding regularly follows extended periods of drought, flushing out inland river systems, overflowing dams and inundating large inland flood plains, as occurred throughout Eastern Australia in 2010, 2011 and 2012 after the 2000s Australian drought.

Australia's carbon dioxide emissions per capita are among the highest in the world, lower than those of only a few other industrialised nations.[163]

January 2019 was the hottest month ever in Australia with average temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F).[164][165]

The 2019–20 Australian bushfire season was Australia's worst bushfire season on record.[166]

Biodiversity

Although most of Australia is semi-arid or desert, the continent includes a diverse range of habitats from alpine heaths to tropical rainforests. Fungi typify that diversity—an estimated 250,000 species—of which only 5% have been described—occur in Australia.[167] Because of the continent's great age, extremely variable weather patterns, and long-term geographic isolation, much of Australia's biota is unique. About 85% of flowering plants, 84% of mammals, more than 45% of birds, and 89% of in-shore, temperate-zone fish are endemic.[168] Australia has at least 755 species of reptile, more than any other country in the world.[169] Besides Antarctica, Australia is the only continent that developed without feline species. Feral cats may have been introduced in the 17th century by Dutch shipwrecks, and later in the 18th century by European settlers. They are now considered a major factor in the decline and extinction of many vulnerable and endangered native species.[170]

Australian forests are mostly made up of evergreen species, particularly eucalyptus trees in the less arid regions; wattles replace them as the dominant species in drier regions and deserts.[171] Among well-known Australian animals are the monotremes (the platypus and echidna); a host of marsupials, including the kangaroo, koala, and wombat, and birds such as the emu and the kookaburra.[171] Australia is home to many dangerous animals including some of the most venomous snakes in the world.[172] The dingo was introduced by Austronesian people who traded with Indigenous Australians around 3000 BCE.[173] Many animal and plant species became extinct soon after first human settlement,[174] including the Australian megafauna; others have disappeared since European settlement, among them the thylacine.[175][176]

Many of Australia's ecoregions, and the species within those regions, are threatened by human activities and introduced animal, chromistan, fungal and plant species.[177] All these factors have led to Australia's having the highest mammal extinction rate of any country in the world.[178] The federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 is the legal framework for the protection of threatened species.[179] Numerous protected areas have been created under the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity to protect and preserve unique ecosystems;[180][181] 65 wetlands are listed under the Ramsar Convention,[182] and 16 natural World Heritage Sites have been established.[183] Australia was ranked 21st out of 178 countries in the world on the 2018 Environmental Performance Index.[184] There are more than 1,800 animals and plants on Australia's threatened species list, including more than 500 animals.[185]

Government and politics

Australia is a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy.[186] The country has maintained a stable liberal democratic political system under its constitution, which is one of the world's oldest, since Federation in 1901. It is also one of the world's oldest federations, in which power is divided between the federal and state and territorial governments. The Australian system of government combines elements derived from the political systems of the United Kingdom (a fused executive, constitutional monarchy and strong party discipline) and the United States (federalism, a written constitution and strong bicameralism with an elected upper house), along with distinctive indigenous features.[187][188]

The federal government is separated into three branches:

- Legislature: the bicameral Parliament, comprising the monarch (represented by the governor-general), the Senate, and the House of Representatives;

- Executive: the Federal Executive Council, which in practice gives legal effect to the decisions of the cabinet, comprising the prime minister and other ministers of state appointed by the governor-general on the advice of Parliament;[189]

- Judiciary: the High Court of Australia and other federal courts, whose judges are appointed by the governor-general on advice of Parliament

Elizabeth II reigns as Queen of Australia and is represented in Australia by the governor-general at the federal level and by the governors at the state level, who by convention act on the advice of her ministers.[190][191] Thus, in practice the governor-general acts as a legal figurehead for the actions of the prime minister and the Federal Executive Council. The governor-general does have extraordinary reserve powers which may be exercised outside the prime minister's request in rare and limited circumstances, the most notable exercise of which was the dismissal of the Whitlam Government in the constitutional crisis of 1975.[192]

In the Senate (the upper house), there are 76 senators: twelve each from the states and two each from the mainland territories (the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory).[193] The House of Representatives (the lower house) has 151 members elected from single-member electoral divisions, commonly known as "electorates" or "seats", allocated to states on the basis of population,[194] with each original state guaranteed a minimum of five seats.[195] Elections for both chambers are normally held every three years simultaneously; senators have overlapping six-year terms except for those from the territories, whose terms are not fixed but are tied to the electoral cycle for the lower house; thus only 40 of the 76 places in the Senate are put to each election unless the cycle is interrupted by a double dissolution.[193]

Australia's electoral system uses preferential voting for all lower house elections with the exception of Tasmania and the ACT which, along with the Senate and most state upper houses, combine it with proportional representation in a system known as the single transferable vote. Voting is compulsory for all enrolled citizens 18 years and over in every jurisdiction,[196] as is enrolment (with the exception of South Australia).[197] The party with majority support in the House of Representatives forms the government and its leader becomes Prime Minister. In cases where no party has majority support, the Governor-General has the constitutional power to appoint the Prime Minister and, if necessary, dismiss one that has lost the confidence of Parliament.[198]

There are two major political groups that usually form government, federally and in the states: the Australian Labor Party and the Coalition which is a formal grouping of the Liberal Party and its minor partner, the National Party.[199][200] Within Australian political culture, the Coalition is considered centre-right and the Labor Party is considered centre-left.[201] Independent members and several minor parties have achieved representation in Australian parliaments, mostly in upper houses. The Australian Greens are often considered the "third force" in politics, being the third largest party by both vote and membership.[202]

The most recent federal election was held on 18 May 2019 and resulted in the Coalition, led by Prime Minister Scott Morrison, retaining government.[203]

States and territories

Australia has six states—New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (QLD), South Australia (SA), Tasmania (TAS), Victoria (VIC) and Western Australia (WA)—and two major mainland territories—the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and the Northern Territory (NT). In most respects, these two territories function as states, except that the Commonwealth Parliament has the power to modify or repeal any legislation passed by the territory parliaments.[204]

Under the constitution, the states essentially have plenary legislative power to legislate on any subject, whereas the Commonwealth (federal) Parliament may legislate only within the subject areas enumerated under section 51. For example, state parliaments have the power to legislate with respect to education, criminal law and state police, health, transport, and local government, but the Commonwealth Parliament does not have any specific power to legislate in these areas.[205] However, Commonwealth laws prevail over state laws to the extent of the inconsistency.[206] In addition, the Commonwealth has the power to levy income tax which, coupled with the power to make grants to States, has given it the financial means to incentivise States to pursue specific legislative agendas within areas over which the Commonwealth does not have legislative power.

Each state and major mainland territory has its own parliament—unicameral in the Northern Territory, the ACT and Queensland, and bicameral in the other states. The states are sovereign entities, although subject to certain powers of the Commonwealth as defined by the Constitution. The lower houses are known as the Legislative Assembly (the House of Assembly in South Australia and Tasmania); the upper houses are known as the Legislative Council. The head of the government in each state is the Premier and in each territory the Chief Minister. The Queen is represented in each state by a governor; and in the Northern Territory, the administrator.[207] In the Commonwealth, the Queen's representative is the governor-general.[208]

The Commonwealth Parliament also directly administers the external territories of Ashmore and Cartier Islands, the Australian Antarctic Territory, Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, the Coral Sea Islands, and Heard Island and McDonald Islands, as well as the internal Jervis Bay Territory, a naval base and sea port for the national capital in land that was formerly part of New South Wales.[189] The external territory of Norfolk Island previously exercised considerable autonomy under the Norfolk Island Act 1979 through its own legislative assembly and an Administrator to represent the Queen.[209] In 2015, the Commonwealth Parliament abolished self-government, integrating Norfolk Island into the Australian tax and welfare systems and replacing its legislative assembly with a council.[210] Macquarie Island is part of Tasmania,[211] and Lord Howe Island of New South Wales.[212]

Foreign relations

.jpg)

Over recent decades, Australia's foreign relations have been driven by a close association with the United States through the ANZUS pact, and by a desire to develop relationships with Asia and the Pacific, particularly through ASEAN, the Pacific Islands Forum and the Pacific Community, of which Australia is a founding member. In 2005 Australia secured an inaugural seat at the East Asia Summit following its accession to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, and in 2011 attended the Sixth East Asia Summit in Indonesia. Australia is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, in which the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings provide the main forum for co-operation.[213] Australia has pursued the cause of international trade liberalisation.[214] It led the formation of the Cairns Group and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.[215][216]

Australia is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Trade Organization,[217][218] and has pursued several major bilateral free trade agreements, most recently the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement[219] and Closer Economic Relations with New Zealand,[220] with another free trade agreement being negotiated with China—the Australia–China Free Trade Agreement—and Japan,[221] South Korea in 2011,[222][223] Australia–Chile Free Trade Agreement, and as of November 2015 has put the Trans-Pacific Partnership before parliament for ratification.[224]

Australia maintains a deeply integrated relationship with neighbouring New Zealand, with free mobility of citizens between the two countries under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement and free trade under the Australia–New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement.[225] New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom are the most favourably viewed countries in the world by Australian people,[226][227] sharing a number of close diplomatic, military and cultural ties with Australia.

Along with New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Malaysia and Singapore, Australia is party to the Five Power Defence Arrangements, a regional defence agreement. A founding member country of the United Nations, Australia is strongly committed to multilateralism[228] and maintains an international aid program under which some 60 countries receive assistance. The 2005–06 budget provides A$2.5 billion for development assistance.[229] Australia ranks fifteenth overall in the Center for Global Development's 2012 Commitment to Development Index.[230]

Military

Australia's armed forces—the Australian Defence Force (ADF)—comprise the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), the Australian Army and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), in total numbering 81,214 personnel (including 57,982 regulars and 23,232 reservists) as of November 2015. The titular role of Commander-in-Chief is vested in the Governor-General, who appoints a Chief of the Defence Force from one of the armed services on the advice of the government.[231] Day-to-day force operations are under the command of the Chief, while broader administration and the formulation of defence policy is undertaken by the Minister and Department of Defence.

In the 2016–17 budget, defence spending comprised 2% of GDP, representing the world's 12th largest defence budget.[232] Australia has been involved in UN and regional peacekeeping, disaster relief and armed conflict, including the 2003 invasion of Iraq; Australia currently has deployed about 2,241 personnel in varying capacities to 12 international operations in areas including Iraq and Afghanistan.[233]

Economy

A wealthy country, Australia has a market economy, a high GDP per capita, and a relatively low rate of poverty. In terms of average wealth, Australia ranked second in the world after Switzerland from 2013 until 2018.[235] In 2018, Australia overtook Switzerland and became the country with the highest average wealth.[235] Australia's poverty rate increased from 10.2% to 11.8%, from 2000/01 to 2013.[236][237] It was identified by the Credit Suisse Research Institute as the nation with the highest median wealth in the world and the second-highest average wealth per adult in 2013.[236]

The Australian dollar is the currency for the nation, including Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island, as well as the independent Pacific Island states of Kiribati, Nauru, and Tuvalu. With the 2006 merger of the Australian Stock Exchange and the Sydney Futures Exchange, the Australian Securities Exchange became the ninth largest in the world.[238]

Ranked fifth in the Index of Economic Freedom (2017),[239] Australia is the world's 14th largest economy and has the tenth highest per capita GDP (nominal) at US$55,692.[240] The country was ranked third in the United Nations 2017 Human Development Index.[241] Melbourne reached top spot for the fourth year in a row on The Economist's 2014 list of the world's most liveable cities,[242] followed by Adelaide, Sydney, and Perth in the fifth, seventh, and ninth places respectively. Total government debt in Australia is about A$190 billion[243]—20% of GDP in 2010.[244] Australia has among the highest house prices and some of the highest household debt levels in the world.[245]

An emphasis on exporting commodities rather than manufactured goods has underpinned a significant increase in Australia's terms of trade since the start of the 21st century, due to rising commodity prices. Australia has a balance of payments that is more than 7% of GDP negative, and has had persistently large current account deficits for more than 50 years.[246] Australia has grown at an average annual rate of 3.6% for over 15 years, in comparison to the OECD annual average of 2.5%.[246]

Australia was the only advanced economy not to experience a recession due to the global financial downturn in 2008–2009.[247] However, the economies of six of Australia's major trading partners have been in recession, which in turn has affected Australia, significantly hampering its economic growth in recent years.[248][249] From 2012 to early 2013, Australia's national economy grew, but some non-mining states and Australia's non-mining economy experienced a recession.[250][251][252]

The Hawke Government floated the Australian dollar in 1983 and partially deregulated the financial system.[253] The Howard Government followed with a partial deregulation of the labour market and the further privatisation of state-owned businesses, most notably in the telecommunications industry.[254] The indirect tax system was substantially changed in July 2000 with the introduction of a 10% Goods and Services Tax (GST).[255] In Australia's tax system, personal and company income tax are the main sources of government revenue.[256]

As of September 2018, there were 12,640,800 people employed (either full- or part-time), with an unemployment rate of 5.2%.[257] Data released in mid-November 2013 showed that the number of welfare recipients had grown by 55%. In 2007 228,621 Newstart unemployment allowance recipients were registered, a total that increased to 646,414 in March 2013.[258] According to the Graduate Careers Survey, full-time employment for newly qualified professionals from various occupations has declined since 2011 but it increases for graduates three years after graduation.[259][260]

Since 2008, inflation has typically been 2–3% and the base interest rate 5–6%. The service sector of the economy, including tourism, education, and financial services, accounts for about 70% of GDP.[261] Rich in natural resources, Australia is a major exporter of agricultural products, particularly wheat and wool, minerals such as iron-ore and gold, and energy in the forms of liquified natural gas and coal. Although agriculture and natural resources account for only 3% and 5% of GDP respectively, they contribute substantially to export performance. Australia's largest export markets are Japan, China, the United States, South Korea, and New Zealand.[262] Australia is the world's fourth largest exporter of wine, and the wine industry contributes A$5.5 billion per year to the nation's economy.[263]

Access to biocapacity in Australia is much higher than world average. In 2016, Australia had 12.3 global hectares[264] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[265] In 2016 Australia used 6.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use half as much biocapacity as Australia contains. As a result, Australia is running a biocapacity reserve.[264]

In 2020 ACOSS released a new report revealing that poverty is growing in Australia, with an estimated 3.2 million people, or 13.6% of the population, living below the internationally accepted poverty line of 50% of a country's median income. It also estimated that there are 774,000 (17.7%) children under the age of 15 that are in poverty.[266][267]

Demographics

Australia has an average population density of 3.3 persons per square kilometre of total land area, which makes it is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world. The population is heavily concentrated on the east coast, and in particular in the south-eastern region between South East Queensland to the north-east and Adelaide to the south-west.[268]

Australia is highly urbanised, with 67% of the population living in the Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (metropolitan areas of the state and mainland territorial capital cities) in 2018.[269] Metropolitan areas with more than one million inhabitants are Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide.

In common with many other developed countries, Australia is experiencing a demographic shift towards an older population, with more retirees and fewer people of working age. In 2018 the average age of the Australian population was 38.8 years.[270] In 2015, 2.15% of the Australian population lived overseas, one of the lowest proportions worldwide.[271]

Ancestry and immigration

| Country of birth (2019)[273] | |

| Birthplace[N 8] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 17,836,000 |

| England | 986,460 |

| Mainland China | 677,240 |

| India | 660,350 |

| New Zealand | 570,000 |

| Philippines | 293,770 |

| Vietnam | 262,910 |

| South Africa | 193,860 |

| Italy | 182,520 |

| Malaysia | 175,920 |

| Sri Lanka | 140,260 |

| Scotland | 133,920 |

| Nepal | 117,870 |

| South Korea | 116,030 |

| Germany | 112,420 |

| Greece | 106,660 |

| United States | 108,570 |

| Hong Kong | 101,290 |

| Total foreign-born | 7,529,570 |

Between 1788 and the Second World War, the vast majority of settlers and immigrants came from the British Isles (principally England, Ireland and Scotland), although there was significant immigration from China and Germany during the 19th century. In the decades immediately following the Second World War, Australia received a large wave of immigration from across Europe, with many more immigrants arriving from Southern and Eastern Europe than in previous decades. Since the end of the White Australia policy in 1973, Australia has pursued an official policy of multiculturalism,[274] and there has been a large and continuing wave of immigration from across the world, with Asia being the largest source of immigrants in the 21st century.[275]

Today, Australia has the world's eighth-largest immigrant population, with immigrants accounting for 30% of the population, a higher proportion than in any other nation with a population of over 10 million.[27][276] 160,323 permanent immigrants were admitted to Australia in 2018–19 (excluding refugees),[275] whilst there was a net population gain of 239,600 people from all permanent and temporary immigration in that year.[277] The majority of immigrants are skilled,[275] but the immigration program includes categories for family members and refugees.[277] In 2019 the largest foreign-born populations were those born in England (3.9%), Mainland China (2.7%), India (2.6%), New Zealand (2.2%), the Philippines (1.2%) and Vietnam (1%).[27]

In the 2016 Australian census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 9][278][279]

- English (36.1%)

- Australian (33.5%)[N 10]

- Irish (11.0%)

- Scottish (9.3%)

- Chinese (5.6%)

- Italian (4.6%)

- German (4.5%)

- Indian (2.8%)

- Indigenous (2.8%)[N 11]

- Greek (1.8%)

- Dutch (1.6%)

- Filipino (1.4%)

- Vietnamese (1.4%)

- Lebanese (1%)

At the 2016 census, 649,171 people (2.8% of the total population) identified as being Indigenous—Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.[N 12][281] Indigenous Australians experience higher than average rates of imprisonment and unemployment, lower levels of education, and life expectancies for males and females that are, respectively, 11 and 17 years lower than those of non-indigenous Australians.[262][282][283] Some remote Indigenous communities have been described as having "failed state"-like conditions.[284]

Language

Although Australia has no official language, English is the de facto national language.[2] Australian English is a major variety of the language with a distinctive accent and lexicon,[285] and differs slightly from other varieties of English in grammar and spelling.[286] General Australian serves as the standard dialect.

According to the 2016 census, English is the only language spoken in the home for 72.7% of the population. The next most common languages spoken at home are Mandarin (2.5%), Arabic (1.4%), Cantonese (1.2%), Vietnamese (1.2%) and Italian (1.2%).[278] A considerable proportion of first- and second-generation migrants are bilingual.

Over 250 Indigenous Australian languages are thought to have existed at the time of first European contact,[287] of which fewer than twenty are still in daily use by all age groups.[288][289] About 110 others are spoken exclusively by older people.[289] At the time of the 2006 census, 52,000 Indigenous Australians, representing 12% of the Indigenous population, reported that they spoke an Indigenous language at home.[290] Australia has a sign language known as Auslan, which is the main language of about 10,112 deaf people who reported that they spoke Auslan language at home in the 2016 census.[291]

Religion

Australia has no state religion; Section 116 of the Australian Constitution prohibits the federal government from making any law to establish any religion, impose any religious observance, or prohibit the free exercise of any religion.[293] In the 2016 census, 52.1% of Australians were counted as Christian, including 22.6% as Catholic and 13.3% as Anglican; 30.1% of the population reported having "no religion"; 8.2% identify with non-Christian religions, the largest of these being Islam (2.6%), followed by Buddhism (2.4%), Hinduism (1.9%), Sikhism (0.5%) and Judaism (0.4%). The remaining 9.7% of the population did not provide an adequate answer. Those who reported having no religion increased conspicuously from 19% in 2006 to 22% in 2011 to 30.1% in 2016.[292]

Before European settlement, the animist beliefs of Australia's indigenous people had been practised for many thousands of years. Mainland Aboriginal Australians' spirituality is known as the Dreamtime and it places a heavy emphasis on belonging to the land. The collection of stories that it contains shaped Aboriginal law and customs. Aboriginal art, story and dance continue to draw on these spiritual traditions. The spirituality and customs of Torres Strait Islanders, who inhabit the islands between Australia and New Guinea, reflected their Melanesian origins and dependence on the sea. The 1996 Australian census counted more than 7000 respondents as followers of a traditional Aboriginal religion.[294]

Since the arrival of the First Fleet of British ships in 1788, Christianity has become the major religion practised in Australia. Christian churches have played an integral role in the development of education, health and welfare services in Australia. For much of Australian history, the Church of England (now known as the Anglican Church of Australia) was the largest religious denomination, with a large Roman Catholic minority. However, multicultural immigration has contributed to a steep decline in its relative position since the Second World War. Similarly, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism and Judaism have all grown in Australia over the past half-century.[295]

Australia has one of the lowest levels of religious adherence in the world.[296] In 2001, only 8.8% of Australians attended church on a weekly basis.[297]

Health

Australia's life expectancy is the third highest in the world for males and the seventh highest for females.[298] Life expectancy in Australia in 2010 was 79.5 years for males and 84.0 years for females.[299] Australia has the highest rates of skin cancer in the world,[300] while cigarette smoking is the largest preventable cause of death and disease, responsible for 7.8% of the total mortality and disease. Ranked second in preventable causes is hypertension at 7.6%, with obesity third at 7.5%.[301][302] Australia ranks 35th in the world[303] and near the top of developed nations for its proportion of obese adults[304] and nearly two thirds (63%) of its adult population is either overweight or obese.[305]

Total expenditure on health (including private sector spending) is around 9.8% of GDP.[306] Australia introduced universal health care in 1975.[307] Known as Medicare, it is now nominally funded by an income tax surcharge known as the Medicare levy, currently at 2%.[308] The states manage hospitals and attached outpatient services, while the Commonwealth funds the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (subsidising the costs of medicines) and general practice.[307]

Education

School attendance, or registration for home schooling,[310] is compulsory throughout Australia. Education is the responsibility of the individual states and territories[311] so the rules vary between states, but in general children are required to attend school from the age of about 5 until about 16.[312][313] In some states (e.g., Western Australia,[314] the Northern Territory[315] and New South Wales[316][317]), children aged 16–17 are required to either attend school or participate in vocational training, such as an apprenticeship.

Australia has an adult literacy rate that was estimated to be 99% in 2003.[318] However, a 2011–12 report for the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that Tasmania has a literacy and numeracy rate of only 50%.[319] In the Programme for International Student Assessment, Australia regularly scores among the top five of thirty major developed countries (member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Catholic education accounts for the largest non-government sector.

Australia has 37 government-funded universities and two private universities, as well as a number of other specialist institutions that provide approved courses at the higher education level.[320] The OECD places Australia among the most expensive nations to attend university.[321] There is a state-based system of vocational training, known as TAFE, and many trades conduct apprenticeships for training new tradespeople.[322] About 58% of Australians aged from 25 to 64 have vocational or tertiary qualifications,[262] and the tertiary graduation rate of 49% is the highest among OECD countries. 30.9 percent of Australia's population has attained a higher education qualification, which is among the highest percentages in the world.[323][324][325]

Australia has the highest ratio of international students per head of population in the world by a large margin, with 812,000 international students enrolled in the nation's universities and vocational institutions in 2019.[326][327] Accordingly, in 2019, international students represented on average 26.7% of the student bodies of Australian universities. International education therefore represents one of the country's largest exports and has a pronounced influence on the country's demographics, with a significant proportion of international students remaining in Australia after graduation on various skill and employment visas.[328]

Culture

Since 1788, the primary influence behind Australian culture has been Anglo-Celtic Western culture, with some Indigenous influences.[330][331] The divergence and evolution that has occurred in the ensuing centuries has resulted in a distinctive Australian culture.[332][333] The culture of the United States has also been highly influential, particularly through television and cinema. Other cultural influences come from neighbouring Asian countries, and through large-scale immigration from non-English-speaking nations.[334]

Arts

Australia has over 100,000 Aboriginal rock art sites,[335] and traditional designs, patterns and stories infuse contemporary Indigenous Australian art, "the last great art movement of the 20th century" according to critic Robert Hughes;[336] its exponents include Emily Kame Kngwarreye.[337] Early colonial artists showed a fascination with the unfamiliar land.[338] The impressionistic works of Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and other members of the 19th-century Heidelberg School—the first "distinctively Australian" movement in Western art—gave expression to nationalist sentiments in the lead-up to Federation.[338] While the school remained influential into the 1900s, modernists such as Margaret Preston, and, later, Sidney Nolan and Arthur Boyd, explored new artistic trends.[338] The landscape remained a central subject matter for Fred Williams, Brett Whiteley and other post-war artists whose works, eclectic in style yet uniquely Australian, moved between the figurative and the abstract.[338][339] The national and state galleries maintain collections of local and international art.[340] Australia has one of the world's highest attendances of art galleries and museums per head of population.[341]

Australian literature grew slowly in the decades following European settlement though Indigenous oral traditions, many of which have since been recorded in writing, are much older.[343] In the 1870s, Adam Lindsay Gordon posthumously became the first Australian poet to attain a wide readership. Following in his footsteps, Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson captured the experience of the bush using a distinctive Australian vocabulary.[344] Their works are still popular; Paterson's bush poem "Waltzing Matilda" (1895) is regarded as Australia's unofficial national anthem.[345] Miles Franklin is the namesake of Australia's most prestigious literary prize, awarded annually to the best novel about Australian life.[346] Its first recipient, Patrick White, went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973.[347] Australian Booker Prize winners include Peter Carey, Thomas Keneally and Richard Flanagan.[348] Author David Malouf, playwright David Williamson and poet Les Murray are also renowned.[349][350]

Many of Australia's performing arts companies receive funding through the federal government's Australia Council.[351] There is a symphony orchestra in each state,[352] and a national opera company, Opera Australia,[353] well known for its famous soprano Joan Sutherland.[354] At the beginning of the 20th century, Nellie Melba was one of the world's leading opera singers.[355] Ballet and dance are represented by The Australian Ballet and various state companies. Each state has a publicly funded theatre company.[356]

Media

The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), the world's first feature-length narrative film, spurred a boom in Australian cinema during the silent film era.[357] After World War I, Hollywood monopolised the industry,[358] and by the 1960s Australian film production had effectively ceased.[359] With the benefit of government support, the Australian New Wave of the 1970s brought provocative and successful films, many exploring themes of national identity, such as Wake in Fright and Gallipoli,[360] while Crocodile Dundee and the Ozploitation movement's Mad Max series became international blockbusters.[361] In a film market flooded with foreign content, Australian films delivered a 7.7% share of the local box office in 2015.[362] The AACTAs are Australia's premier film and television awards, and notable Academy Award winners from Australia include Geoffrey Rush, Nicole Kidman, Cate Blanchett and Heath Ledger.[363]

Australia has two public broadcasters (the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the multicultural Special Broadcasting Service), three commercial television networks, several pay-TV services,[364] and numerous public, non-profit television and radio stations. Each major city has at least one daily newspaper,[364] and there are two national daily newspapers, The Australian and The Australian Financial Review.[364] In 2010, Reporters Without Borders placed Australia 18th on a list of 178 countries ranked by press freedom, behind New Zealand (8th) but ahead of the United Kingdom (19th) and United States (20th).[365] This relatively low ranking is primarily because of the limited diversity of commercial media ownership in Australia;[366] most print media are under the control of News Corporation and, after Fairfax Media was merged with Nine, Nine Entertainment Co.[367]

Cuisine

Most Indigenous Australian groups subsisted on a simple hunter-gatherer diet of native fauna and flora, otherwise called bush tucker.[368] The first settlers introduced British food to the continent, much of which is now considered typical Australian food, such as the Sunday roast.[369][370] Multicultural immigration transformed Australian cuisine; post-World War II European migrants, particularly from the Mediterranean, helped to build a thriving Australian coffee culture, and the influence of Asian cultures has led to Australian variants of their staple foods, such as the Chinese-inspired dim sim and Chiko Roll.[371] Vegemite, pavlova, lamingtons and meat pies are regarded as iconic Australian foods.[372] Australian wine is produced mainly in the southern, cooler parts of the country.

Australia is also known for its cafe and coffee culture in urban centres, which has influenced coffee culture abroad, including New York City.[373] Australia was responsible for the flat white coffee–purported to have originated in a Sydney cafe in the mid-1980s.[374]

Sport and recreation

Cricket and football are the predominate sports in Australia during the summer and winter months, respectively. Australia is unique in that it has professional leagues for four football codes. Originating in Melbourne in the 1850s, Australian rules football is the most popular code in all states except New South Wales and Queensland, where rugby league holds sway, followed by rugby union. Soccer, while ranked fourth in popularity and resources, has the highest overall participation rates.[376] Cricket is popular across all borders and has been regarded by many Australians as the national sport. The Australian national cricket team competed against England in the first Test match (1877) and the first One Day International (1971), and against New Zealand in the first Twenty20 International (2004), winning all three games. It has also participated in every edition of the Cricket World Cup, winning the tournament a record five times.[377]

Australia is a powerhouse in water-based sports, such as swimming and surfing.[378] The surf lifesaving movement originated in Australia, and the volunteer lifesaver is one of the country's icons.[379] Nationally, other popular sports include horse racing, basketball, and motor racing. The annual Melbourne Cup horse race and the Sydney to Hobart yacht race attract intense interest.[380] In 2016, the Australian Sports Commission revealed that swimming, cycling and soccer are the three most popular participation sports.[381][382]

Australia is one of five nations to have participated in every Summer Olympics of the modern era,[383] and has hosted the Games twice: 1956 in Melbourne and 2000 in Sydney.[384] Australia has also participated in every Commonwealth Games,[385] hosting the event in 1938, 1962, 1982, 2006 and 2018.[386] Australia made its inaugural appearance at the Pacific Games in 2015. As well as being a regular FIFA World Cup participant, Australia has won the OFC Nations Cup four times and the AFC Asian Cup once—the only country to have won championships in two different FIFA confederations.[387] In June 2020, Australia won its bid to co-host the 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup with New Zealand.[388][389] The country regularly competes among the world elite basketball teams as it is among the global top three teams in terms of qualifications to the Basketball Tournament at the Summer Olympics. Other major international events held in Australia include the Australian Open tennis grand slam tournament, international cricket matches, and the Australian Formula One Grand Prix. The highest-rating television programs include sports telecasts such as the Summer Olympics, FIFA World Cup, The Ashes, Rugby League State of Origin, and the grand finals of the National Rugby League and Australian Football League.[390] Skiing in Australia began in the 1860s and snow sports take place in the Australian Alps and parts of Tasmania.

Notes

- Australia's royal anthem is "God Save the Queen", played in the presence of a member of the Royal family when they are in Australia. In other contexts, the national anthem of Australia, "Advance Australia Fair", is played.[1]

- English does not have de jure status.[2]

- Religion was an optional question on the Census, so percentages for individual religions do not add up to 100%[3]

- There are minor variations from three basic time zones; see Time in Australia.

- The earliest recorded use of the word Australia in English was in 1625 in "A note of Australia del Espíritu Santo, written by Sir Richard Hakluyt", published by Samuel Purchas in Hakluytus Posthumus, a corruption of the original Spanish name "Austrialia del Espíritu Santo" (Southern Land of the Holy Spirit)[33][34][35] for an island in Vanuatu.[36] The Dutch adjectival form australische was used in a Dutch book in Batavia (Jakarta) in 1638, to refer to the newly discovered lands to the south.[37]

- For instance, the 1814 work A Voyage to Terra Australis.

- Australia describes the body of water south of its mainland as the Southern Ocean, rather than the Indian Ocean as defined by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). In 2000, a vote of IHO member nations defined the term "Southern Ocean" as applying only to the waters between Antarctica and 60 degrees south latitude.[111]

- In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, Mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- As a percentage of 21,769,209 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census. The Australian Census collects information on ancestry, but not on race or ethnicity.

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[280]

- Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References

- "Australian National Anthem". Archived from the original on 1 July 2007.

"16. Other matters – 16.3 Australian National Anthem". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

"National Symbols" (PDF). Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia (PDF) (29th ed.). 2005 [2002]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007. - "Pluralist Nations: Pluralist Language Policies?". 1995 Global Cultural Diversity Conference Proceedings, Sydney. Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2009. "English has no de jure status but it is so entrenched as the common language that it is de facto the official language as well as the national language."

- "Religion in Australia". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- See entry in the Macquarie Dictionary.

- Collins English Dictionary. Bishopbriggs, Glasgow: HarperCollins. 2009. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-00-786171-2.

- "Population clock". Australian Bureau of Statistics website. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 23 July 2020. The population estimate shown is automatically calculated daily at 00:00 UTC and is based on data obtained from the population clock on the date shown in the citation.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Australia". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "Australia". International Monetary Fund. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Inequality in Australia" (PDF). University of New South Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Style manual for authors, editors and printers (6 ed.). John Wiley & Sons Australia. 2002. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7016-3647-0.

- "Constitution of Australia". ComLaw. 9 July 1900. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

3. It shall be lawful for the Queen, with the advice of the Privy Council, to declare by proclamation that, on and after a day therein appointed, not being later than one year after the passing of this Act, the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania, and also, if Her Majesty is satisfied that the people of Western Australia have agreed thereto, of Western Australia, shall be united in a Federal Commonwealth under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- "Geographic Distribution of the Population". 24 May 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833.

- Korsch RJ.; et al. (2011). "Australian island arcs through time: Geodynamic implications for the Archean and Proterozoic". Gondwana Research. 19 (3): 716–734. Bibcode:2011GondR..19..716K. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.11.018.

- Macey, Richard (21 January 2005). "Map from above shows Australia is a very flat place". The Sydney Morning Herald. ISSN 0312-6315. OCLC 226369741. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- "The Australian continent". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Deserts". Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Kelly, Karina (13 September 1995). "A Chat with Tim Flannery on Population Control". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010. "Well, Australia has by far the world's least fertile soils".

- Grant, Cameron (August 2007). "Damaged Dirt" (PDF). The Advertiser. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

Australia has the oldest, most highly weathered soils on the planet.

- "Australia's Size Compared". Geoscience Australia. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- Cassen, Robert (1982). Rich Country Interests and Third World Development. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7099-1930-8.

- "Australia, wealthiest nation in the world". 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Australians the world's wealthiest". The Sydney Morning Herald. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Data refer mostly to the year 2017. World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018, International Monetary Fund. Accessed on 1 April 2019.

- "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2017" (PDF). www.sipri.org.

- "Main Features – Australia's Population by Country of Birth". 3412.0 – Migration, Australia, 2018-19. Commonwealth of Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 April 2020.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, (2015). 'International Migration' in International migrant stock 2015. Accessed from International migrant stock 2015: maps on 24 May 2017.

- "Australia: World Audit Democracy Profile". WorldAudit.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- Dyett, Kathleen (19 August 2014). "Melbourne named world's most liveable city for the fourth year running, beating Adelaide, Sydney and Perth" Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, ABC News. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Australian pronunciations: Macquarie Dictionary, Fourth Edition (2005). Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-876429-14-3

- "Australia" Archived 23 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "He named it Austrialia del Espiritu Santo and claimed it for Spain" Archived 17 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Spanish quest for Terra Australis | State Library of New South Wales Page 1.

- "A note on 'Austrialia' or 'Australia' Rupert Gerritsen – Journal of The Australian and New Zealand Map Society Inc. The Globe, Number 72, 2013 " Archived 12 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine Posesion en nombre de Su Magestad (Archivo del Museo Naval, Madrid, MS 951) p. 3.

- "The Illustrated Sydney News". Illustrated Sydney News. National Library of Australia. 26 January 1888. p. 2. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Purchas, vol. iv, pp. 1422–32, 1625.

- Scott, Ernest (2004) [1914]. The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders. Kessinger Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-4191-6948-9.

- Flinders, Matthew (1814). A Voyage to Terra Australis. G. and W. Nicol.

- Philip Clarke, "Putting 'Australia' on the map", The Conversation, 10 August 2014.

- "Who Named Australia?". The Mail (Adelaide, SA). Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 11 February 1928. p. 16. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- Weekend Australian, 30–31 December 2000, p. 16

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2007). Life in Australia (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-921446-30-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Brian J. Coman A Loose Canon: Essays on History, Modernity and Tradition, Ch. 5, "La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo: Captain Quiros and the Discovery of Australia in 1606", p. 40. Retrieved 16 February 2017

- Meanings and origins of Australian words and idioms Archived 8 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, ANU

- Nunn, Patrick (2018). The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4729-4327-9.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2018). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. Taylor & Francis. pp. 250–253. ISBN 978-1-351-75764-5.

- Oppenheimer, Stephen (2013). Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World. Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-78033-753-1.

- Gilligan, Ian (2018). Climate, Clothing, and Agriculture in Prehistory: Linking Evidence, Causes, and Effects. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-108-47008-7.

- Tuniz, Claudio; Gillespie, Richard; Jones, Cheryl (2016). The Bone Readers: Science and Politics in Human Origins Research. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-315-41888-9.

- Castillo, Alicia (2015). Archaeological Dimension of World Heritage: From Prevention to Social Implications. Springer Science. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4939-0283-5.

- "The spread of people to Australia". Australian Museum.

- "Aboriginal Australians the oldest culture on Earth". Australian Geographic. 18 May 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Williams, Elizabeth (2015). "Complex hunter-gatherers: a view from Australia". Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. 61 (232): 310–321. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00052182.

- Sáenz, Rogelio; Embrick, David G.; Rodríguez, Néstor P. (3 June 2015). The International Handbook of the Demography of Race and Ethnicity. Springer. pp. 602–. ISBN 978-90-481-8891-8.

- 1301.0 – Year Book Australia, 2002 Australian Bureau of Statistics 25 January 2002

- also see other historians including Noel Butlin (1983) Our Original Aggression George Allen and Unwin, Sydney. ISBN 0-86861-223-5

- Galván, Javier A. (2014). They Do What? A Cultural Encyclopedia of Extraordinary and Exotic Customs from around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-61069-342-4.

- Viegas, Jennifer (3 July 2008). "Early Aussie Tattoos Match Rock Art". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- MacKnight, CC (1976). The Voyage to Marege: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia. Melbourne University Press.

- Barber, Peter; Barnes, Katherine; Dr Nigel Erskine (2013). Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita To Australia. National Library of Australia. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-642-27809-8.

- Smith, Claire; Burke, Heather (2007). Digging It Up Down Under: A Practical Guide to Doing Archaeology in Australia. Springer Science. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-387-35263-3.

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, p. 233

- Brett Hilder (1980) The Voyage of Torres. University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Queensland. ISBN 0-7022-1275-X

- Davis, Russell Earls (2019). A Concise History of Western Australia. Woodslane Press. ISBN 9781925868227, pp. 3–6.

- Baer, Joel (2005). Pirates of the British Isles. Gloucestershire: Tempus. pp. 66–68. ISBN 978-0-7524-2304-3. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Marsh, Lindsay (2010). History of Australia : understanding what makes Australia the place it is today. Greenwood, W.A.: Ready-Ed Publications. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-86397-798-2.

- Goucher, Candice; Walton, Linda (2013). World History: Journeys from Past to Present. Routledge. pp. 427–28. ISBN 978-1-135-08829-3.

- "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia". Australian Government: Culture Portal. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

[The British] moved north to Port Jackson on 26 January 1788, landing at Camp Cove, known as 'cadi' to the Cadigal people. Governor Phillip carried instructions to establish the first British Colony in Australia. The First Fleet was under prepared for the task, and the soil around Sydney Cove was poor.

- Egan, Ted (2003). The Land Downunder. Grice Chapman Publishing. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-9545726-0-0.

- Matsuda, Matt K. (2012). Pacific Worlds: A History of Seas, Peoples, and Cultures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521887632, pp. 165–167.

- "Smallpox Through History". Encarta. Archived from the original on 18 June 2004.

- Attwood, Bain; Foster, Stephen Glynn (2003). Frontier Conflict: The Australian Experience. National Museum of Australia. ISBN 978-1-876944-11-7, p. 89.

- Attwood, Bain (2005). Telling the truth about Aboriginal history. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-577-9.

- Edwards, William Howell (2004). An Introduction to Aboriginal Societies. Cengage Learning Australia. pp. 132–33. ISBN 978-1-876633-89-9.

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, pp. 5–7, 402

- Davison, Hirst and Macintyre, pp. 464–65, 628–29