Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the Corpus Juris Civilis (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I. Roman law forms the basic framework for civil law, the most widely used legal system today, and the terms are sometimes used synonymously. The historical importance of Roman law is reflected by the continued use of Latin legal terminology in many legal systems influenced by it, including common law.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of ancient Rome |

| Periods |

|

| Roman Constitution |

| Precedent and law |

|

|

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Titles and honours |

After the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire, the Roman law remained in effect in the Eastern Roman Empire. From the 7th century onward, the legal language in the East was Greek.

Roman law also denoted the legal system applied in most of Western Europe until the end of the 18th century. In Germany, Roman law practice remained in place longer under the Holy Roman Empire (963–1806). Roman law thus served as a basis for legal practice throughout Western continental Europe, as well as in most former colonies of these European nations, including Latin America, and also in Ethiopia. English and Anglo-American common law were influenced also by Roman law, notably in their Latinate legal glossary (for example, stare decisis, culpa in contrahendo, pacta sunt servanda).[1] Eastern Europe was also influenced by the jurisprudence of the Corpus Juris Civilis, especially in countries such as medieval Romania (Wallachia, Moldavia, and some other medieval provinces/historical regions) which created a new system, a mixture of Roman and local law. Also, Eastern European law was influenced by the "Farmer's Law" of the medieval Byzantine legal system.

Development

Before the Twelve Tables (754–449 BC), private law comprised the Roman civil law (ius civile Quiritium) that applied only to Roman citizens, and was bonded to religion; undeveloped, with attributes of strict formalism, symbolism, and conservatism, e.g. the ritual practice of mancipatio (a form of sale). The jurist Sextus Pomponius said, "At the beginning of our city, the people began their first activities without any fixed law, and without any fixed rights: all things were ruled despotically, by kings".[2] It is believed that Roman Law is rooted in the Etruscan religion, emphasizing ritual.[3]

Twelve Tables

The first legal text is the Law of the Twelve Tables, dating from the mid-5th century BC. The plebeian tribune, C. Terentilius Arsa, proposed that the law should be written in order to prevent magistrates from applying the law arbitrarily.[4] After eight years of political struggle, the plebeian social class convinced the patricians to send a delegation to Athens to copy the Laws of Solon; they also dispatched delegations to other Greek cities for like reason.[4] In 451 BC, according to the traditional story (as Livy tells it), ten Roman citizens were chosen to record the laws, known as the decemviri legibus scribundis. While they were performing this task, they were given supreme political power (imperium), whereas the power of the magistrates was restricted.[4] In 450 BC, the decemviri produced the laws on ten tablets (tabulae), but these laws were regarded as unsatisfactory by the plebeians. A second decemvirate is said to have added two further tablets in 449 BC. The new Law of the Twelve Tables was approved by the people's assembly.[4]

Modern scholars tend to challenge the accuracy of Roman historians. They generally do not believe that a second decemvirate ever took place. The decemvirate of 451 is believed to have included the most controversial points of customary law, and to have assumed the leading functions in Rome.[4] Furthermore, questions concerning Greek influence on early Roman Law are still much discussed. Many scholars consider it unlikely that the patricians sent an official delegation to Greece, as the Roman historians believed. Instead, those scholars suggest, the Romans acquired Greek legislations from the Greek cities of Magna Graecia, the main portal between the Roman and Greek worlds.[4] The original text of the Twelve Tables has not been preserved. The tablets were probably destroyed when Rome was conquered and burned by the Gauls in 387 BC.[4]

The fragments which did survive show that it was not a law code in the modern sense. It did not provide a complete and coherent system of all applicable rules or give legal solutions for all possible cases. Rather, the tables contained specific provisions designed to change the then-existing customary law. Although the provisions pertain to all areas of law, the largest part is dedicated to private law and civil procedure.

Early law and jurisprudence

Many laws include Lex Canuleia (445 BC; which allowed the marriage—ius connubii—between patricians and plebeians), Leges Licinae Sextiae (367 BC; which made restrictions on possession of public lands—ager publicus—and also made sure that one of the consuls was plebeian), Lex Ogulnia (300 BC; plebeians received access to priest posts), and Lex Hortensia (287 BC; verdicts of plebeian assemblies—plebiscita—now bind all people).

Another important statute from the Republican era is the Lex Aquilia of 286 BC, which may be regarded as the root of modern tort law. However, Rome's most important contribution to European legal culture was not the enactment of well-drafted statutes, but the emergence of a class of professional jurists (prudentes, sing. prudens, or jurisprudentes) and of a legal science. This was achieved in a gradual process of applying the scientific methods of Greek philosophy to the subject of law, a subject which the Greeks themselves never treated as a science.

Traditionally, the origins of Roman legal science are connected to Gnaeus Flavius. Flavius is said to have published around the year 300 BC the formularies containing the words which had to be spoken in court to begin a legal action. Before the time of Flavius, these formularies are said to have been secret and known only to the priests. Their publication made it possible for non-priests to explore the meaning of these legal texts. Whether or not this story is credible, jurists were active and legal treatises were written in larger numbers before the 2nd century BC. Among the famous jurists of the republican period are Quintus Mucius Scaevola who wrote a voluminous treatise on all aspects of the law, which was very influential in later times, and Servius Sulpicius Rufus, a friend of Marcus Tullius Cicero. Thus, Rome had developed a very sophisticated legal system and a refined legal culture when the Roman republic was replaced by the monarchical system of the principate in 27 BC.

Pre-classical period

In the period between about 201 to 27 BC, we can see the development of more flexible laws to match the needs of the time. In addition to the old and formal ius civile a new juridical class is created: the ius honorarium, which can be defined as "The law introduced by the magistrates who had the right to promulgate edicts in order to support, supplement or correct the existing law."[5] With this new law the old formalism is being abandoned and new more flexible principles of ius gentium are used.

The adaptation of law to new needs was given over to juridical practice, to magistrates, and especially to the praetors. A praetor was not a legislator and did not technically create new law when he issued his edicts (magistratuum edicta). In fact, the results of his rulings enjoyed legal protection (actionem dare) and were in effect often the source of new legal rules. A Praetor's successor was not bound by the edicts of his predecessor; however, he did take rules from edicts of his predecessor that had proved to be useful. In this way a constant content was created that proceeded from edict to edict (edictum traslatitium).

Thus, over the course of time, parallel to the civil law and supplementing and correcting it, a new body of praetoric law emerged. In fact, praetoric law was so defined by the famous Roman jurist Papinian (142–212 AD): "Ius praetorium est quod praetores introduxerunt adiuvandi vel supplendi vel corrigendi iuris civilis gratia propter utilitatem publicam" ("praetoric law is that law introduced by praetors to supplement or correct civil law for public benefit"). Ultimately, civil law and praetoric law were fused in the Corpus Juris Civilis.

Classical Roman law

The first 250 years of the current era are the period during which Roman law and Roman legal science reached its greatest degree of sophistication. The law of this period is often referred to as the classical period of Roman law. The literary and practical achievements of the jurists of this period gave Roman law its unique shape.

The jurists worked in different functions: They gave legal opinions at the request of private parties. They advised the magistrates who were entrusted with the administration of justice, most importantly the praetors. They helped the praetors draft their edicts, in which they publicly announced at the beginning of their tenure, how they would handle their duties, and the formularies, according to which specific proceedings were conducted. Some jurists also held high judicial and administrative offices themselves.

The jurists also produced all kinds of legal punishments. Around AD 130 the jurist Salvius Iulianus drafted a standard form of the praetor's edict, which was used by all praetors from that time onwards. This edict contained detailed descriptions of all cases, in which the praetor would allow a legal action and in which he would grant a defense. The standard edict thus functioned like a comprehensive law code, even though it did not formally have the force of law. It indicated the requirements for a successful legal claim. The edict therefore became the basis for extensive legal commentaries by later classical jurists like Paulus and Ulpian. The new concepts and legal institutions developed by pre-classical and classical jurists are too numerous to mention here. Only a few examples are given here:

- Roman jurists clearly separated the legal right to use a thing (ownership) from the factual ability to use and manipulate the thing (possession). They also established the distinction between contract and tort as sources of legal obligations.

- The standard types of contract (sale, contract for work, hire, contract for services) regulated in most continental codes and the characteristics of each of these contracts were developed by Roman jurisprudence.

- The classical jurist Gaius (around 160) invented a system of private law based on the division of all material into personae (persons), res (things) and actiones (legal actions). This system was used for many centuries. It can be recognized in legal treatises like William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and enactments like the French Code civil or the German BGB.

The Roman Republic had three different branches:

The Assemblies could decide whether war or peace. The Senate had complete control over the Treasury, and the Consuls had the highest juridical power.[6]

Post-classical law

By the middle of the 3rd century, the conditions for the flourishing of a refined legal culture had become less favourable. The general political and economic situation deteriorated as the emperors assumed more direct control of all aspects of political life. The political system of the principate, which had retained some features of the republican constitution, began to transform itself into the absolute monarchy of the dominate. The existence of a legal science and of jurists who regarded law as a science, not as an instrument to achieve the political goals set by the absolute monarch, did not fit well into the new order of things. The literary production all but ended. Few jurists after the mid-3rd century are known by name. While legal science and legal education persisted to some extent in the eastern part of the Empire, most of the subtleties of classical law came to be disregarded and finally forgotten in the west. Classical law was replaced by so-called vulgar law.

Substance

Concept of laws

- ius civile, ius gentium, and ius naturale – the ius civile ("citizen law", originally ius civile Quiritium) was the body of common laws that applied to Roman citizens and the Praetores Urbani, the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens. The ius gentium ("law of peoples") was the body of common laws that applied to foreigners, and their dealings with Roman citizens. The Praetores Peregrini were the individuals who had jurisdiction over cases involving citizens and foreigners. Jus naturale was a concept the jurists developed to explain why all people seemed to obey some laws. Their answer was that a "natural law" instilled in all beings a common sense.

- ius scriptum and ius non-scriptum – meaning written and unwritten law, respectively. In practice, the two differed by the means of their creation and not necessarily whether or not they were written down. The ius scriptum was the body of statute laws made by the legislature. The laws were known as leges (lit. "laws") and plebiscita (lit. "plebiscites," originating in the Plebeian Council). Roman lawyers would also include in the ius scriptum the edicts of magistrates (magistratuum edicta), the advice of the Senate (Senatus consulta), the responses and thoughts of jurists (responsa prudentium), and the proclamations and beliefs of the emperor (principum placita). Ius non-scriptum was the body of common laws that arose from customary practice and had become binding over time.

- ius commune and ius singulare – Ius singulare (singular law) is special law for certain groups of people, things, or legal relations (because of which it is an exception from the general rules of the legal system), unlike general, ordinary, law (ius commune). An example of this is the law about wills written by people in the military during a campaign, which are exempt of the solemnities generally required for citizens when writing wills in normal circumstances.

- ius publicum and ius privatum – ius publicum means public law and ius privatum means private law, where public law is to protect the interests of the Roman state while private law should protect individuals. In the Roman law ius privatum included personal, property, civil and criminal law; judicial proceeding was private process (iudicium privatum); and crimes were private (except the most severe ones that were prosecuted by the state). Public law will only include some areas of private law close to the end of the Roman state. Ius publicum was also used to describe obligatory legal regulations (today called ius cogens—this term is applied in modern international law to indicate peremptory norms that cannot be derogated from). These are regulations that cannot be changed or excluded by party agreement. Those regulations that can be changed are called today ius dispositivum, and they are not used when party shares something and are in contrary.

Public law

The Roman Republic's constitution or mos maiorum ("custom of the ancestors") was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. Concepts that originated in the Roman constitution live on in constitutions to this day. Examples include checks and balances, the separation of powers, vetoes, filibusters, quorum requirements, term limits, impeachments, the powers of the purse, and regularly scheduled elections. Even some lesser used modern constitutional concepts, such as the block voting found in the electoral college of the United States, originate from ideas found in the Roman constitution.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was not formal or even official. Its constitution was largely unwritten, and was constantly evolving throughout the life of the Republic. Throughout the 1st century BC, the power and legitimacy of the Roman constitution was progressively eroding. Even Roman constitutionalists, such as the senator Cicero, lost a willingness to remain faithful to it towards the end of the republic. When the Roman Republic ultimately fell in the years following the Battle of Actium and Mark Antony's suicide, what was left of the Roman constitution died along with the Republic. The first Roman Emperor, Augustus, attempted to manufacture the appearance of a constitution that still governed the Empire, by utilising that constitution's institutions to lend legitimacy to the Principate, e.g. reusing prior grants of greater imperium to substantiate Augustus' greater imperium over the Imperial provinces and the prorogation of different magistracies to justify Augustus' receipt of tribunician power. The belief in a surviving constitution lasted well into the life of the Roman Empire.

Private law

Stipulatio was the basic form of contract in Roman law. It was made in the format of question and answer. The precise nature of the contract was disputed, as can be seen below.

Rei vindicatio is a legal action by which the plaintiff demands that the defendant return a thing that belongs to the plaintiff. It may only be used when plaintiff owns the thing, and the defendant is somehow impeding the plaintiff's possession of the thing. The plaintiff could also institute an actio furti (a personal action) to punish the defendant. If the thing could not be recovered, the plaintiff could claim damages from the defendant with the aid of the condictio furtiva (a personal action). With the aid of the actio legis Aquiliae (a personal action), the plaintiff could claim damages from the defendant. Rei vindicatio was derived from the ius civile, therefore was only available to Roman citizens.

Status

To describe a person's position in the legal system, Romans mostly used the expression togeus. The individual could have been a Roman citizen (status civitatis) unlike foreigners, or he could have been free (status libertatis) unlike slaves, or he could have had a certain position in a Roman family (status familiae) either as the head of the family (pater familias), or some lower member—alieni iuris—which lives by someone else's law. Two status types were senator and emperor.

Litigation

The history of Roman Law can be divided into three systems of procedure: that of legis actiones, the formulary system, and cognitio extra ordinem. The periods in which these systems were in use overlapped one another and did not have definitive breaks, but it can be stated that the legis actio system prevailed from the time of the XII Tables (c. 450 BC) until about the end of the 2nd century BC, that the formulary procedure was primarily used from the last century of the Republic until the end of the classical period (c. AD 200), and that of cognitio extra ordinem was in use in post-classical times. Again, these dates are meant as a tool to help understand the types of procedure in use, not as a rigid boundary where one system stopped and another began.[7]

During the republic and until the bureaucratization of Roman judicial procedure, the judge was usually a private person (iudex privatus). He had to be a Roman male citizen. The parties could agree on a judge, or they could appoint one from a list, called album iudicum. They went down the list until they found a judge agreeable to both parties, or if none could be found they had to take the last one on the list.

No one had a legal obligation to judge a case. The judge had great latitude in the way he conducted the litigation. He considered all the evidence and ruled in the way that seemed just. Because the judge was not a jurist or a legal technician, he often consulted a jurist about the technical aspects of the case, but he was not bound by the jurist's reply. At the end of the litigation, if things were not clear to him, he could refuse to give a judgment, by swearing that it wasn't clear. Also, there was a maximum time to issue a judgment, which depended on some technical issues (type of action, etc.).

Later on, with the bureaucratization, this procedure disappeared, and was substituted by the so-called "extra ordinem" procedure, also known as cognitory. The whole case was reviewed before a magistrate, in a single phase. The magistrate had obligation to judge and to issue a decision, and the decision could be appealed to a higher magistrate.

Legacy

German legal theorist Rudolf von Jhering famously remarked that ancient Rome had conquered the world three times: the first through its armies, the second through its religion, the third through its laws. He might have added: each time more thoroughly.

— David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years

In the East

When the centre of the Empire was moved to the Greek East in the 4th century, many legal concepts of Greek origin appeared in the official Roman legislation.[8] The influence is visible even in the law of persons or of the family, which is traditionally the part of the law that changes least. For example, Constantine started putting restrictions on the ancient Roman concept of patria potestas, the power held by the male head of a family over his descendants, by acknowledging that persons in potestate, the descendants, could have proprietary rights. He was apparently making concessions to the much stricter concept of paternal authority under Greek-Hellenistic law.[8] The Codex Theodosianus (438 AD) was a codification of Constantian laws. Later emperors went even further, until Justinian finally decreed that a child in potestate became owner of everything it acquired, except when it acquired something from its father.[8]

The codes of Justinian, particularly the Corpus Juris Civilis (529–534) continued to be the basis of legal practice in the Empire throughout its so-called Byzantine history. Leo III the Isaurian issued a new code, the Ecloga,[9] in the early 8th century. In the 9th century, the emperors Basil I and Leo VI the Wise commissioned a combined translation of the Code and the Digest, parts of Justinian's codes, into Greek, which became known as the Basilica. Roman law as preserved in the codes of Justinian and in the Basilica remained the basis of legal practice in Greece and in the courts of the Eastern Orthodox Church even after the fall of the Byzantine Empire and the conquest by the Turks, and, along with the Syro-Roman law book, also formed the basis for much of the Fetha Negest, which remained in force in Ethiopia until 1931.

In the West

In the west, Justinian's political authority never went any farther than certain portions of the Italian and Hispanic peninsulas. In Law codes were issued by the Germanic kings, however, the influence of early Eastern Roman codes on some of these is quite discernible. In many early Germanic states, Roman citizens continued to be governed by Roman laws for quite some time, even while members of the various Germanic tribes were governed by their own respective codes.

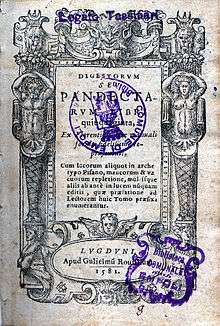

The Codex Justinianus and the Institutes of Justinian were known in Western Europe, and along with the earlier code of Theodosius II, served as models for a few of the Germanic law codes; however, the Digest portion was largely ignored for several centuries until around 1070, when a manuscript of the Digest was rediscovered in Italy. This was done mainly through the works of glossars who wrote their comments between lines (glossa interlinearis), or in the form of marginal notes (glossa marginalis). From that time, scholars began to study the ancient Roman legal texts, and to teach others what they learned from their studies. The center of these studies was Bologna. The law school there gradually developed into Europe's first university.

The students who were taught Roman law in Bologna (and later in many other places) found that many rules of Roman law were better suited to regulate complex economic transactions than were the customary rules, which were applicable throughout Europe. For this reason, Roman law, or at least some provisions borrowed from it, began to be re-introduced into legal practice, centuries after the end of the Roman empire. This process was actively supported by many kings and princes who employed university-trained jurists as counselors and court officials and sought to benefit from rules like the famous Princeps legibus solutus est ("The sovereign is not bound by the laws", a phrase initially coined by Ulpian, a Roman jurist).

There are several reasons that Roman law was favored in the Middle Ages. Roman law regulated the legal protection of property and the equality of legal subjects and their wills, and it prescribed the possibility that the legal subjects could dispose their property through testament.

By the middle of the 16th century, the rediscovered Roman law dominated the legal practice of many European countries. A legal system, in which Roman law was mixed with elements of canon law and of Germanic custom, especially feudal law, had emerged. This legal system, which was common to all of continental Europe (and Scotland) was known as Ius Commune. This Ius Commune and the legal systems based on it are usually referred to as civil law in English-speaking countries.

Only England and the Nordic countries did not take part in the wholesale reception of Roman law. One reason for this is that the English legal system was more developed than its continental counterparts by the time Roman law was rediscovered. Therefore, the practical advantages of Roman law were less obvious to English practitioners than to continental lawyers. As a result, the English system of common law developed in parallel to Roman-based civil law, with its practitioners being trained at the Inns of Court in London rather than receiving degrees in Canon or Civil Law at the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge. Elements of Romano-canon law were present in England in the ecclesiastical courts and, less directly, through the development of the equity system. In addition, some concepts from Roman law made their way into the common law. Especially in the early 19th century, English lawyers and judges were willing to borrow rules and ideas from continental jurists and directly from Roman law.

The practical application of Roman law, and the era of the European Ius Commune, came to an end when national codifications were made. In 1804, the French civil code came into force. In the course of the 19th century, many European states either adopted the French model or drafted their own codes. In Germany, the political situation made the creation of a national code of laws impossible. From the 17th century, Roman law in Germany had been heavily influenced by domestic (customary) law, and it was called usus modernus Pandectarum. In some parts of Germany, Roman law continued to be applied until the German civil code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB) went into effect in 1900.[10]

Colonial expansion spread the civil law system.[11]

Today

Today, Roman law is no longer applied in legal practice, even though the legal systems of some countries like South Africa and San Marino are still based on the old jus commune. However, even where the legal practice is based on a code, many rules deriving from Roman law apply: no code completely broke with the Roman tradition. Rather, the provisions of the Roman law were fitted into a more coherent system and expressed in the national language. For this reason, knowledge of the Roman law is indispensable to understand the legal systems of today. Thus, Roman law is often still a mandatory subject for law students in civil law jurisdictions.

As steps towards a unification of the private law in the member states of the European Union are being taken, the old jus commune, which was the common basis of legal practice everywhere in Europe, but allowed for many local variants, is seen by many as a model.

See also

- Abalienatio (legal transfer of property)

- Auctoritas (power of the sovereign)

- Basileus (akin to modern sovereign)

- Capitis deminutio

- Certiorari

- Cessio bonorum (surrender of goods to a creditor)

- Compascuus (common pasture)

- Constitution (Roman law)

- Homo sacer

- Interregnum

- Justitium (akin to modern state of exception)

- Lex Caecilia Didia

- Lex Duodecim Tabularum

- Lex Junia Licinia

- Lex Manciana

- List of Roman laws

- Res extra commercium

- Roman-Dutch law

- Stipulatio

- Ancient Greek law

References

- In Germany, Art. 311 BGB

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Jenő Szmodis: The Reality of the Law – From the Etruscan Religion to the Postmodern Theories of Law; Ed. Kairosz, Budapest, 2005.

- "A Short History of Roman Law", Olga Tellegen-Couperus pp. 19–20.

- Berger, Adolf (1953). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. The American Journal of Philology. 76. pp. 90–93. doi:10.2307/297597. ISBN 9780871694324. JSTOR 291711.

- "Consul". Livius.org. 2002. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Jolowicz, Herbert Felix; Nicholas, Barry (1967). Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 528. ISBN 9780521082532.

- Tellegen-Couperus, Olga Eveline (1993). A Short History of Roman Law. Psychology Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780415072502.

- "Ecloga". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Wolff, Hans Julius, 1902-1983. (1951). Roman law : an historical introduction. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 208. ISBN 0585116784. OCLC 44953814.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rheinstein, Max; Glendon, Mary Ann; Carozza, Paolo. "Civil law (Romano-Germanic)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

Sources

- Berger, Adolf, "Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 43, Part 2., pp. 476. Philadelphia : American Philosophical Society, 1953. (reprinted 1980, 1991, 2002). ISBN 1-58477-142-9

Further reading

- Bablitz, Leanne E. 2007. Actors and Audience in the Roman Courtroom. London: Routledge.

- Bauman, Richard A. 1989. Lawyers and Politics in the Early Roman Empire. Munich: Beck.

- Borkowski, Andrew, and Paul Du Plessis. 2005. A Textbook on Roman Law. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Buckland, William Warwick. 1963. A Textbook of Roman Law from Augustus to Justinian. Revised by P. G. Stein. 3d edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Daube, David. 1969. Roman Law: Linguistic, Social and Philosophical Aspects. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press.

- De Ligt, Luuk. 2007. "Roman Law and the Roman Economy: Three Case Studies." Latomus 66.1: 10–25.

- du Plessis, Paul. 2006. "Janus in the Roman Law of Urban Lease." Historia 55.1: 48–63.

- Gardner, Jane F. 1986. Women in Roman Law and Society. London: Croom Helm.

- Gardner, Jane F. 1998. Family and Familia in Roman Law and Life. Clarendon Press.

- Harries, Jill. 1999. Law and Empire in Late Antiquity. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nicholas, Barry. 1962. An Introduction to Roman Law. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Nicholas, Barry, and Peter Birks, eds. 1989. New Perspectives in the Roman Law of Property. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Powell, Jonathan, and Jeremy Paterson, eds. 2004. Cicero the Advocate. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Rives, James B. 2003. "Magic in Roman Law: The Reconstruction of a Crime." Classical Antiquity 22.2: 313–39.

- Schulz, Fritz. 1946. History of Roman Legal Science. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Stein, Peter. 1999. Roman Law in European History. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Tellegen-Couperus, Olga E. 1993. A Short History of Roman Law. London: Routledge.

- Wenger, Leopold. 1953. Die Quellen des römischen Rechts. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.