Architecture

Architecture (Latin architectura, from the Greek ἀρχιτέκτων arkhitekton "architect", from ἀρχι- "chief" and τέκτων "creator") is both the process and the product of planning, designing, and constructing buildings or other structures.[3] Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural symbols and as works of art. Historical civilizations are often identified with their surviving architectural achievements.[4]

_De_Cotte_2503c_%E2%80%93_Gallica_2011_(adjusted).jpg)

Definitions

Architecture can mean:

- A general term to describe buildings and other physical structures.[5]

- The art and science of designing buildings and (some) nonbuilding structures.[5]

- The style of design and method of construction of buildings and other physical structures.[5]

- A unifying or coherent form or structure.[6]

- Knowledge of art, science, technology, and humanity.[5]

- The design activity of the architect,[5] from the macro-level (urban design, landscape architecture) to the micro-level (construction details and furniture). The practice of the architect, where architecture means offering or rendering professional services in connection with the design and construction of buildings, or built environments.[7]

Theory of architecture

The philosophy of architecture is a branch of philosophy of art, dealing with aesthetic value of architecture, its semantics and relations with development of culture. Many philosophers and theoreticians from Plato to Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Robert Venturi and Ludwig Wittgenstein have concerned themselves with the nature of architecture and whether or not architecture is distinguished from building.[8]

Historic treatises

The earliest surviving written work on the subject of architecture is De architectura by the Roman architect Vitruvius in the early 1st century AD.[9] According to Vitruvius, a good building should satisfy the three principles of firmitas, utilitas, venustas,[10][11] commonly known by the original translation – firmness, commodity and delight. An equivalent in modern English would be:

- Durability – a building should stand up robustly and remain in good condition

- Utility – it should be suitable for the purposes for which it is used

- Beauty – it should be aesthetically pleasing

According to Vitruvius, the architect should strive to fulfill each of these three attributes as well as possible. Leon Battista Alberti, who elaborates on the ideas of Vitruvius in his treatise, De re aedificatoria, saw beauty primarily as a matter of proportion, although ornament also played a part. For Alberti, the rules of proportion were those that governed the idealised human figure, the Golden mean.

The most important aspect of beauty was, therefore, an inherent part of an object, rather than something applied superficially, and was based on universal, recognisable truths. The notion of style in the arts was not developed until the 16th century, with the writing of Vasari.[12] By the 18th century, his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects had been translated into Italian, French, Spanish, and English.

In the early 19th century, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin wrote Contrasts (1836) that, as the titled suggested, contrasted the modern, industrial world, which he disparaged, with an idealized image of neo-medieval world. Gothic architecture, Pugin believed, was the only "true Christian form of architecture."

The 19th-century English art critic, John Ruskin, in his Seven Lamps of Architecture, published 1849, was much narrower in his view of what constituted architecture. Architecture was the "art which so disposes and adorns the edifices raised by men ... that the sight of them" contributes "to his mental health, power, and pleasure".[13] For Ruskin, the aesthetic was of overriding significance. His work goes on to state that a building is not truly a work of architecture unless it is in some way "adorned". For Ruskin, a well-constructed, well-proportioned, functional building needed string courses or rustication, at the very least.[13]

On the difference between the ideals of architecture and mere construction, the renowned 20th-century architect Le Corbusier wrote: "You employ stone, wood, and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces: that is construction. Ingenuity is at work. But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good. I am happy and I say: This is beautiful. That is Architecture".[14]

Le Corbusier's contemporary Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said "Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins."[15]

Modern concepts

The notable 19th-century architect of skyscrapers, Louis Sullivan, promoted an overriding precept to architectural design: "Form follows function".

While the notion that structural and aesthetic considerations should be entirely subject to functionality was met with both popularity and skepticism, it had the effect of introducing the concept of "function" in place of Vitruvius' "utility". "Function" came to be seen as encompassing all criteria of the use, perception and enjoyment of a building, not only practical but also aesthetic, psychological and cultural.

Nunzia Rondanini stated, "Through its aesthetic dimension architecture goes beyond the functional aspects that it has in common with other human sciences. Through its own particular way of expressing values, architecture can stimulate and influence social life without presuming that, in and of itself, it will promote social development.'

To restrict the meaning of (architectural) formalism to art for art's sake is not only reactionary; it can also be a purposeless quest for perfection or originality which degrades form into a mere instrumentality".[16]

Among the philosophies that have influenced modern architects and their approach to building design are Rationalism, Empiricism, Structuralism, Poststructuralism, Deconstruction and Phenomenology.

In the late 20th century a new concept was added to those included in the compass of both structure and function, the consideration of sustainability, hence sustainable architecture. To satisfy the contemporary ethos a building should be constructed in a manner which is environmentally friendly in terms of the production of its materials, its impact upon the natural and built environment of its surrounding area and the demands that it makes upon non-sustainable power sources for heating, cooling, water and waste management, and lighting.

History

Origins and vernacular architecture

Building first evolved out of the dynamics between needs (shelter, security, worship, etc.) and means (available building materials and attendant skills). As human cultures developed and knowledge began to be formalized through oral traditions and practices, building became a craft, and "architecture" is the name given to the most highly formalized and respected versions of that craft. It is widely assumed that architectural success was the product of a process of trial and error, with progressively less trial and more replication as the results of the process proved increasingly satisfactory. What is termed vernacular architecture continues to be produced in many parts of the world.

Prehistoric architecture

Early human settlements were mostly rural. Expending economies resulted in the creation of urban areas which in some cases grew and evolved very rapidly, such as that of Çatal Höyük in Anatolia and Mohenjo Daro of the Indus Valley Civilization in modern-day Pakistan.

Neolithic settlements and "cities" include Göbekli Tepe and Çatalhöyük in Turkey, Jericho in the Levant, Mehrgarh in Pakistan, Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, Orkney Islands, Scotland, and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture settlements in Romania, Moldova and Ukraine.

Ancient architecture

In many ancient civilizations such as those of Egypt and Mesopotamia, architecture and urbanism reflected the constant engagement with the divine and the supernatural, and many ancient cultures resorted to monumentality in architecture to represent symbolically the political power of the ruler, the ruling elite, or the state itself.

The architecture and urbanism of the Classical civilizations such as the Greek and the Roman evolved from civic ideals rather than religious or empirical ones and new building types emerged. Architectural "style" developed in the form of the Classical orders. Roman architecture was influenced by Greek architecture as they incorporated many Greek elements into their building practices.[17]

Texts on architecture have been written since ancient time. These texts provided both general advice and specific formal prescriptions or canons. Some examples of canons are found in the writings of the 1st-century BCE Roman Architect Vitruvius. Some of the most important early examples of canonic architecture are religious.

Asian architecture

The architecture of different parts of Asia developed along different lines from that of Europe; Buddhist, Hindu and Sikh architecture each having different characteristics. Indian and Chinese architecture have had great influence on the surrounding regions, while Japanese architecture has not. Buddhist architecture, in particular, showed great regional diversity. Hindu temple architecture, which developed from around the 5th century CE, is in theory governed by concepts laid down in the Shastras, and is concerned with expressing the macrocosm and the microcosm. In many Asian countries, pantheistic religion led to architectural forms that were designed specifically to enhance the natural landscape.

In many parts of Asia, even the grandest houses were relatively lightweight structures mainly using wood until recent times, and there are few survivals of great age. Buddhism was associated with a move to stone and brick religious structures, probably beginning as rock-cut architecture, which has often survived very well.

Early Asian writings on architecture include the Kao Gong Ji of China from the 7th–5th centuries BCE; the Shilpa Shastras of ancient India; Manjusri Vasthu Vidya Sastra of Sri Lanka and Araniko of Nepal .

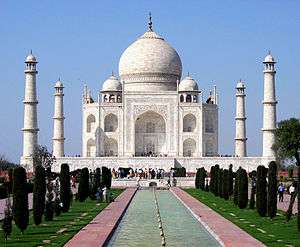

Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture began in the 7th century CE, incorporating architectural forms from the ancient Middle East and Byzantium, but also developing features to suit the religious and social needs of the society. Examples can be found throughout the Middle East, Turkey, North Africa, the Indian Sub-continent and in parts of Europe, such as Spain, Albania, and the Balkan States, as the result of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. [18][19]

Middle Ages

In Europe during the Medieval period, guilds were formed by craftsmen to organize their trades and written contracts have survived, particularly in relation to ecclesiastical buildings. The role of architect was usually one with that of master mason, or Magister lathomorum as they are sometimes described in contemporary documents.

The major architectural undertakings were the buildings of abbeys and cathedrals. From about 900 CE onward, the movements of both clerics and tradesmen carried architectural knowledge across Europe, resulting in the pan-European styles Romanesque and Gothic.

Also, a significant part of the Middle Ages architectural heritage is numerous fortifications across the continent. From Balkans to Spain, and from Malta to Estonia, these buildings represent an important part of European heritage.

Notre Dame de Paris, France.

Notre Dame de Paris, France.- The Tower of London, England.

Renaissance and the architect

In Renaissance Europe, from about 1400 onwards, there was a revival of Classical learning accompanied by the development of Renaissance humanism, which placed greater emphasis on the role of the individual in society than had been the case during the Medieval period. Buildings were ascribed to specific architects – Brunelleschi, Alberti, Michelangelo, Palladio – and the cult of the individual had begun. There was still no dividing line between artist, architect and engineer, or any of the related vocations, and the appellation was often one of regional preference.

A revival of the Classical style in architecture was accompanied by a burgeoning of science and engineering, which affected the proportions and structure of buildings. At this stage, it was still possible for an artist to design a bridge as the level of structural calculations involved was within the scope of the generalist.

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, Italy.

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, Italy. Palazzo Farnese, Rome, Italy.

Palazzo Farnese, Rome, Italy. Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy.

Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy.

Early modern and the industrial age

With the emerging knowledge in scientific fields and the rise of new materials and technology, architecture and engineering began to separate, and the architect began to concentrate on aesthetics and the humanist aspects, often at the expense of technical aspects of building design. There was also the rise of the "gentleman architect" who usually dealt with wealthy clients and concentrated predominantly on visual qualities derived usually from historical prototypes, typified by the many country houses of Great Britain that were created in the Neo Gothic or Scottish baronial styles. Formal architectural training in the 19th century, for example at École des Beaux-Arts in France, gave much emphasis to the production of beautiful drawings and little to context and feasibility.

Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution laid open the door for mass production and consumption. Aesthetics became a criterion for the middle class as ornamented products, once within the province of expensive craftsmanship, became cheaper under machine production.

Vernacular architecture became increasingly ornamental. Housebuilders could use current architectural design in their work by combining features found in pattern books and architectural journals.

Palais Garnier, Paris, France.

Palais Garnier, Paris, France.- Pont Alexandre III Paris, France.

Modernism

Around the beginning of the 20th century, general dissatisfaction with the emphasis on revivalist architecture and elaborate decoration gave rise to many new lines of thought that served as precursors to Modern architecture. Notable among these is the Deutscher Werkbund, formed in 1907 to produce better quality machine-made objects. The rise of the profession of industrial design is usually placed here. Following this lead, the Bauhaus school, founded in Weimar, Germany in 1919, redefined the architectural bounds prior set throughout history, viewing the creation of a building as the ultimate synthesis—the apex—of art, craft, and technology.

When modern architecture was first practised, it was an avant-garde movement with moral, philosophical, and aesthetic underpinnings. Immediately after World War I, pioneering modernist architects sought to develop a completely new style appropriate for a new post-war social and economic order, focused on meeting the needs of the middle and working classes. They rejected the architectural practice of the academic refinement of historical styles which served the rapidly declining aristocratic order. The approach of the Modernist architects was to reduce buildings to pure forms, removing historical references and ornament in favor of functional details. Buildings displayed their functional and structural elements, exposing steel beams and concrete surfaces instead of hiding them behind decorative forms. Architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright developed organic architecture, in which the form was defined by its environment and purpose, with an aim to promote harmony between human habitation and the natural world with prime examples being Robie House and Fallingwater.

Architects such as Mies van der Rohe, Philip Johnson and Marcel Breuer worked to create beauty based on the inherent qualities of building materials and modern construction techniques, trading traditional historic forms for simplified geometric forms, celebrating the new means and methods made possible by the Industrial Revolution, including steel-frame construction, which gave birth to high-rise superstructures. Fazlur Rahman Khan's development of the tube structure was a technological break-through in building ever higher. By mid-century, Modernism had morphed into the International Style, an aesthetic epitomized in many ways by the Twin Towers of New York's World Trade Center designed by Minoru Yamasaki.

Guggenheim Museum, New York City, United States.

Guggenheim Museum, New York City, United States.

Willis Tower, Chicago, United States

Willis Tower, Chicago, United States

Postmodernism

Many architects resisted modernism, finding it devoid of the decorative richness of historical styles. As the first generation of modernists began to die after World War II, the second generation of architects including Paul Rudolph, Marcel Breuer, and Eero Saarinen tried to expand the aesthetics of modernism with Brutalism, buildings with expressive sculptural façades made of unfinished concrete. But an even new younger postwar generation critiqued modernism and Brutalism for being too austere, standardized, monotone, and not taking into account the richness of human experience offered in historical buildings across time and in different places and cultures.

One such reaction to the cold aesthetic of modernism and Brutalism is the school of metaphoric architecture, which includes such things as biomorphism and zoomorphic architecture, both using nature as the primary source of inspiration and design. While it is considered by some to be merely an aspect of postmodernism, others consider it to be a school in its own right and a later development of expressionist architecture.[20]

Beginning in the late 1950s and 1960s, architectural phenomenology emerged as an important movement in the early reaction against modernism, with architects like Charles Moore in the United States, Christian Norberg-Schulz in Norway, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers and Vittorio Gregotti, Michele Valori, Bruno Zevi in Italy, who collectively popularized an interest in a new contemporary architecture aimed at expanding human experience using historical buildings as models and precedents.[21] Postmodernism produced a style that combined contemporary building technology and cheap materials, with the aesthetics of older pre-modern and non-modern styles, from high classical architecture to popular or vernacular regional building styles. Robert Venturi famously defined postmodern architecture as a "decorated shed" (an ordinary building which is functionally designed inside and embellished on the outside), and upheld it against modernist and brutalist "ducks" (buildings with unnecessarily expressive tectonic forms).[22]

- The Petronas Tower in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Architecture today

Since the 1980s, as the complexity of buildings began to increase (in terms of structural systems, services, energy and technologies), the field of architecture became multi-disciplinary with specializations for each project type, technological expertise or project delivery methods. Moreover, there has been an increased separation of the 'design' architect [Notes 1] from the 'project' architect who ensures that the project meets the required standards and deals with matters of liability.[Notes 2] The preparatory processes for the design of any large building have become increasingly complicated, and require preliminary studies of such matters as durability, sustainability, quality, money, and compliance with local laws. A large structure can no longer be the design of one person but must be the work of many. Modernism and Postmodernism have been criticised by some members of the architectural profession who feel that successful architecture is not a personal, philosophical, or aesthetic pursuit by individualists; rather it has to consider everyday needs of people and use technology to create liveable environments, with the design process being informed by studies of behavioral, environmental, and social sciences.

Environmental sustainability has become a mainstream issue, with a profound effect on the architectural profession. Many developers, those who support the financing of buildings, have become educated to encourage the facilitation of environmentally sustainable design, rather than solutions based primarily on immediate cost. Major examples of this can be found in passive solar building design, greener roof designs, biodegradable materials, and more attention to a structure's energy usage. This major shift in architecture has also changed architecture schools to focus more on the environment. There has been an acceleration in the number of buildings that seek to meet green building sustainable design principles. Sustainable practices that were at the core of vernacular architecture increasingly provide inspiration for environmentally and socially sustainable contemporary techniques.[23] The U.S. Green Building Council's LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating system has been instrumental in this.[24]

Concurrently, the recent movements of New Urbanism, metaphoric architecture and New Classical Architecture promote a sustainable approach towards construction that appreciates and develops smart growth, architectural tradition and classical design.[25][26] This in contrast to modernist and globally uniform architecture, as well as leaning against solitary housing estates and suburban sprawl.[27] Glass curtain walls, which were the hallmark of the ultra modern urban life in many countries surfaced even in developing countries like Nigeria where international styles had been represented since the mid 20th Century mostly because of the leanings of foreign-trained architects.[28]

Beijing National Stadium, China.

Beijing National Stadium, China. London City Hall, England.

London City Hall, England. Auditorio de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain.

Auditorio de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain.

Other types of architecture

Landscape architecture

Landscape architecture is the design of outdoor public areas, landmarks, and structures to achieve environmental, social-behavioral, or aesthetic outcomes.[29] It involves the systematic investigation of existing social, ecological, and soil conditions and processes in the landscape, and the design of interventions that will produce the desired outcome. The scope of the profession includes landscape design; site planning; stormwater management; environmental restoration; parks and recreation planning; visual resource management; green infrastructure planning and provision; and private estate and residence landscape master planning and design; all at varying scales of design, planning and management. A practitioner in the profession of landscape architecture is called a landscape architect.

Interior architecture

Interior architecture is the design of a space which has been created by structural boundaries and the human interaction within these boundaries. It can also be the initial design and plan for use, then later redesign to accommodate a changed purpose, or a significantly revised design for adaptive reuse of the building shell.[30] The latter is often part of sustainable architecture practices, conserving resources through "recycling" a structure by adaptive redesign. Generally referred to as the spatial art of environmental design, form and practice, interior architecture is the process through which the interiors of buildings are designed, concerned with all aspects of the human uses of structural spaces. Put simply, interior architecture is the design of an interior in architectural terms.

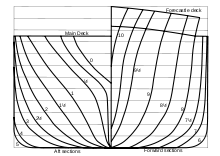

Naval architecture

Naval architecture, also known as naval engineering, is an engineering discipline dealing with the engineering design process, shipbuilding, maintenance, and operation of marine vessels and structures.[31][32] Naval architecture involves basic and applied research, design, development, design evaluation and calculations during all stages of the life of a marine vehicle. Preliminary design of the vessel, its detailed design, construction, trials, operation and maintenance, launching and dry-docking are the main activities involved. Ship design calculations are also required for ships being modified (by means of conversion, rebuilding, modernization, or repair). Naval architecture also involves the formulation of safety regulations and damage control rules and the approval and certification of ship designs to meet statutory and non-statutory requirements.

Urban design

Urban design is the process of designing and shaping the physical features of cities, towns, and villages. In contrast to architecture, which focuses on the design of individual buildings, urban design deals with the larger scale of groups of buildings, streets and public spaces, whole neighborhoods and districts, and entire cities, with the goal of making urban areas functional, attractive, and sustainable.[33]

Urban design is an interdisciplinary field that utilizes elements of many built environment professions, including landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, civil engineering and municipal engineering.[34] It is common for professionals in all these disciplines to practice urban design. In more recent times different sub-subfields of urban design have emerged such as strategic urban design, landscape urbanism, water-sensitive urban design, and sustainable urbanism.

Metaphorical "architectures"

"Architecture" is used as a metaphor for many modern techniques or fields for structuring abstractions. These include:

- Computer architecture, a set of rules and methods that describe the functionality, organization, and implementation of computer systems, with software architecture, hardware architecture and network architecture covering more specific aspects.

- Business architecture, defined as "a blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands",[35] Enterprise architecture is another term.

- Cognitive architecture theories about the structure of the human mind

- System architecture a conceptual model that defines the structure, behavior, and more views of any type of system.[36]

See also

Notes

- A design architect is one who is responsible for the design.

- A project architect is one who is responsible for ensuring the design is built correctly and who administers building contracts – in non-specialist architectural practices the project architect is also the design architect and the term refers to the differing roles the architect plays at differing stages of the process.

References

- Museo Galileo, Museum and Institute of History and Science, The Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore Archived 1 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, (accessed 30 January 2013)

- Giovanni Fanelli, Brunelleschi, Becocci, Florence (1980), Chapter: The Dome pp. 10–41.

- "architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- Pace, Anthony (2004). "Tarxien". In Daniel Cilia (ed.). Malta before History – The World’s Oldest Free Standing Stone Architecture. Miranda Publishers. ISBN 978-9990985085.

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993), Oxford, ISBN 0 19 860575 7

- Merriam–Webster's Dictionary of English Usage, ISBN 0-87779-132-5 or ISBN 978-0-87779-132-4

- "Gov.ns.ca". Gov.ns.ca. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- “It is not the line that is between two points, but the point that is at the intersection of several lines.” Deleuze, Gilles. Pourparlers Paris: Minuit, 1990 p. 219

- D. Rowland – T.N. Howe: Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-00292-3

- "Vitruvius Ten Books on Architecture, with regard to landscape and garden design". gardenvisit.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2005.

- "Vitruvius". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Françoise Choay, Alberti and Vitruvius, editor, Joseph Rykwert, Profile 21, Architectural Design, Vol. 49 No. 5–6

- John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, G. Allen (1880), reprinted Dover, (1989) ISBN 0-486-26145-X

- Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, Dover Publications(1985). ISBN 0-486-25023-7

- "Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins. - Ludwig Mies van der Rohe at BrainyQuote". BrainyQuote.

- Rondanini, Nunzia Architecture and Social Change Heresies II, Vol. 3, No. 3, New York, Neresies Collective Inc., 1981.

- "Introduction to Greek architecture". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Marika Sardar (October 2004). "Essay: The Later Ottomans and the Impact of Europe". www.metmuseum.org. The Met. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Lory, Bernard (1 January 2015). "The Ottoman Legacy in the Balkans" (html / pdf). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Three. Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Three. pp. 355–405. doi:10.1163/9789004290365_006. ISBN 9789004290365. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Fez-Barringten, Barie (2012). Architecture: The Making of Metaphors. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-3517-6.

- Otero-Pailos, Jorge (2010). Architecture's Historical Turn: Phenomenology and the Rise of the Postmodern. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816666041.

- Venturi, Robert (1966). Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

complexity and contradiction in architecture.

- OneWorld.net (31 March 2004). "Vernacular Architecture in India". El.doccentre.info. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- Other energy efficiency and green building rating systems include Energy Star, Green Globes, and CHPS (Collaborative for High Performance Schools).

- "The Charter of the New Urbanism". cnu.org. 20 April 2015.

- "Beauty, Humanism, Continuity between Past and Future". Traditional Architecture Group. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Issue Brief: Smart-Growth: Building Livable Communities. American Institute of Architects. Retrieved on 23 March 2014.

- "Architecture". Litcaf. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, Susan Jellicoe, The Landscape of Man: Shaping the Environment from Prehistory to the Present Day ISBN 9780500274316

- "Interior Architecture". RISD Interior Architecture Graduate Department.

- RINA. "Careers in Naval Architecture". www.rina.org.uk.

- Biran, Adrian; (2003). Ship hydrostatics and stability (1st Ed.) – Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-4988-7

- Boeing; et al. (2014). "LEED-ND and Livability Revisited". Berkeley Planning Journal. 27: 31–55. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., & de Jong, H. (2013). Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems. Planning Theory, 12(2), 177-198.

- OMG Business Architecture Special Interest Group "What Is Business Architecture?" at bawg.omg.org, 2008 (archive.org). Accessed 04-03-2015; Cited in: William M. Ulrich, Philip Newcomb Information Systems Transformation: Architecture-Driven Modernization Case Studies. (2010), p. 4.

- Hannu Jaakkola and Bernhard Thalheim. (2011) "Architecture-driven modelling methodologies." In: Proceedings of the 2011 conference on Information Modelling and Knowledge Bases XXII. Anneli Heimbürger et al. (eds). IOS Press. p. 98

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Architecture. |

- World Architecture Community

- Architecture.com, published by Royal Institute of British Architects

- Architectural centers and museums in the world, list of links from the UIA

- American Institute of Architects

- Glossary of Architectural Terms

- Cities and Buildings Database – Collection of digitized images of buildings and cities drawn from across time and throughout the world from the University of Washington Library

- "Architecture and Power", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Adrian Tinniswood, Gillian Darley and Gavin Stamp (In Our Time, Oct. 31, 2002)