Fahrenheit

The Fahrenheit scale (/ˈfɑːrənhaɪt/) is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736).[1] It uses the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F) as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined his scale exist, but the original paper suggests the lower defining point, 0 °F, was established as the freezing temperature of a solution of brine made from a mixture of water, ice, and ammonium chloride (a salt).[2][3] The other limit established was his best estimate of the average human body temperature (set at 96 °F; about 2.6 °F less than the modern value due to a later redefinition of the scale).[2] However, he noted a middle point of 32 °F, to be set to the temperature of ice water.

| Fahrenheit | |

|---|---|

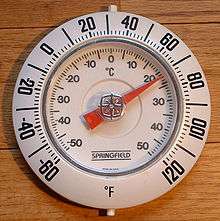

Thermometer with Fahrenheit (marked on outer bezel) and Celsius (marked on inner dial) degree units. The Fahrenheit scale was the first standardized temperature scale to be widely used. | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | Imperial/US customary |

| Unit of | Temperature |

| Symbol | °F |

| Named after | Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit |

| Conversions | |

| x °F in ... | ... is equal to ... |

| °C | 5/9(x − 32) |

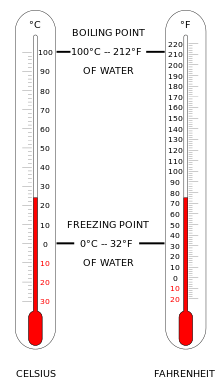

The Fahrenheit scale is now usually defined by two fixed points: the temperature at which pure water freezes into ice is defined as 32 °F and the boiling point of water is defined to be 212 °F, both at sea level and under standard atmospheric pressure (a 180 °F separation).

Fahrenheit was the first standardized temperature scale to be widely used, but its use is now limited. It is the official temperature scale in the United States (including its unincorporated territories), its freely associated states in the Western Pacific (Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands), the Cayman Islands, and Liberia. Fahrenheit is used alongside the Celsius scale in Antigua and Barbuda and other islands which use the same meteorological service, such as Saint Kitts and Nevis, the Bahamas, and Belize. A handful of British Overseas Territories still use both scales, including the British Virgin Islands, Montserrat, Anguilla, and Bermuda.[4] All other countries in the world now officially use the Celsius scale, the name given to the centigrade scale in 1948 in honor of Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius.

Definition and conversion

| from Fahrenheit | to Fahrenheit | |

|---|---|---|

| Celsius | [°C] = ([°F] − 32) × 5⁄9 | [°F] = [°C] × 9⁄5 + 32 |

| Kelvin | [K] = ([°F] + 459.67) × 5⁄9 | [°F] = [K] × 9⁄5 − 459.67 |

| Rankine | [°R] = [°F] + 459.67 | [°F] = [°R] − 459.67 |

| For temperature intervals rather than specific temperatures, 1 °F = 1 °R = 5⁄9 °C = 5⁄9 K Comparisons among various temperature scales | ||

On the Fahrenheit scale, the freezing point of water is 32 degrees Fahrenheit (°F) and the boiling point is 212 °F (at standard atmospheric pressure). This puts the boiling and freezing points of water 180 degrees apart.[5] Therefore, a degree on the Fahrenheit scale is 1⁄180 of the interval between the freezing point and the boiling point. On the Celsius scale, the freezing and boiling points of water are 100 degrees apart. A temperature interval of 1 °F is equal to an interval of 5⁄9 degrees Celsius. The Fahrenheit and Celsius scales intersect at −40° (i.e., −40 °F = −40 °C).

Absolute zero is −273.15 °C or −459.67 °F. The Rankine temperature scale uses degree intervals of the same size as those of the Fahrenheit scale, except that absolute zero is 0 °R — the same way that the Kelvin temperature scale matches the Celsius scale, except that absolute zero is 0 K.[5]

The Fahrenheit scale uses the symbol ° to denote a point on the temperature scale (as does Celsius) and the letter F to indicate the use of the Fahrenheit scale (e.g. "Gallium melts at 85.5763 °F"),[6] as well as to denote a difference between temperatures or an uncertainty in temperature (e.g. "The output of the heat exchanger experiences an increase of 72 °F" and "Our standard uncertainty is ±5 °F").[7]

For an exact conversion, the following formulas can be applied. Here, f is the value in Fahrenheit and c the value in Celsius:

- f °Fahrenheit to c °Celsius : (f − 32) °F × 5°C/9°F = (f − 32)/1.8 °C = c °C

- c °Celsius to f °Fahrenheit : (c °C × 9°F/5°C) + 32 °F = (c × 1.8) °F + 32 °F = f °F

This is also an exact conversion making use of the identity −40 °F = −40 °C. Again, f is the value in Fahrenheit and c the value in Celsius:

- f °Fahrenheit to c °Celsius : ((f + 40) ÷ 1.8) − 40 = c.

- c °Celsius to f °Fahrenheit : ((c + 40) × 1.8) − 40 = f.

History

Fahrenheit proposed his temperature scale in 1724, basing it on two reference points of temperature. In his initial scale (which is not the final Fahrenheit scale), the zero point was determined by placing the thermometer in "a mixture of ice, water, and salis Armoniaci[10] [transl. ammonium chloride] or even sea salt".[11] This combination forms a eutectic system which stabilizes its temperature automatically: 0 °F was defined to be that stable temperature. A second point, 96 degrees, was approximately the human body's temperature (sanguine hominis sani, the blood of a healthy man).[11] A third point, 32 degrees, was marked as being the temperature of ice and water "without the aforementioned salts".[11]

According to a German story, Fahrenheit actually chose the lowest air temperature measured in his hometown Danzig (Gdańsk, Poland) in winter 1708/09 as 0 °F, and only later had the need to be able to make this value reproducible using brine.[12]

According to a letter Fahrenheit wrote to his friend Herman Boerhaave,[13] his scale was built on the work of Ole Rømer, whom he had met earlier. In Rømer's scale, brine freezes at zero, water freezes and melts at 7.5 degrees, body temperature is 22.5, and water boils at 60 degrees. Fahrenheit multiplied each value by four in order to eliminate fractions and make the scale more fine-grained. He then re-calibrated his scale using the melting point of ice and normal human body temperature (which were at 30 and 90 degrees); he adjusted the scale so that the melting point of ice would be 32 degrees and body temperature 96 degrees, so that 64 intervals would separate the two, allowing him to mark degree lines on his instruments by simply bisecting the interval six times (since 64 is 2 to the sixth power).[14][15]

Fahrenheit soon after observed that water boils at about 212 degrees using this scale.[16] The use of the freezing and boiling points of water as thermometer fixed reference points became popular following the work of Anders Celsius and these fixed points were adopted by a committee of the Royal Society led by Henry Cavendish in 1776.[17] Under this system, the Fahrenheit scale is redefined slightly so that the freezing point of water is exactly 32 °F, and the boiling point is exactly 212 °F or 180 degrees higher. It is for this reason that normal human body temperature is approximately 98.6° (oral temperature) on the revised scale (whereas it was 90° on Fahrenheit's multiplication of Rømer, and 96° on his original scale).[18]

In the present-day Fahrenheit scale, 0 °F no longer corresponds to the eutectic temperature of ammonium chloride brine as described above. Instead, that eutectic is at approximately 4 °F on the final Fahrenheit scale.[19]

The Rankine temperature scale was based upon the Fahrenheit temperature scale, with its zero representing absolute zero instead.

Usage

The Fahrenheit scale was the primary temperature standard for climatic, industrial and medical purposes in English-speaking countries until the 1960s. In the late 1960s and 1970s, the Celsius scale replaced Fahrenheit in almost all of those countries—with the notable exception of the United States—typically during their general metrication process.

Fahrenheit is used in the United States, its territories and associated states (all served by the U.S. National Weather Service), as well as the Cayman Islands and Liberia for everyday applications. For example, U.S. weather forecasts, food cooking, and freezing temperatures are typically given in degrees Fahrenheit. Scientists, such as meteorologists, use degrees Celsius or kelvin in all countries.[20]

Early in the 20th century, Halsey and Dale suggested that the resistance to the use of centigrade (now Celsius) system in the U.S. included the larger size of each degree Celsius and the lower zero point in the Fahrenheit system.[21]

Canada has passed legislation favoring the International System of Units, while also maintaining legal definitions for traditional Canadian imperial units.[22] Canadian weather reports are conveyed using degrees Celsius with occasional reference to Fahrenheit especially for cross-border broadcasts. Fahrenheit is still used on virtually all Canadian ovens,[23] Thermometers, both digital and analog, sold in Canada usually employ both the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales.[24][25][26]

In the European Union, it is mandatory to use kelvins or degrees Celsius when quoting temperature for "economic, public health, public safety and administrative" purposes, though degrees Fahrenheit may be used alongside degrees Celsius as a supplementary unit.[27] For example, the laundry symbols used in the United Kingdom follow the recommendations of ISO 3758:2005 showing the temperature of the washing machine water in degrees Celsius only.[28] The equivalent label in North America uses one to six dots to denote temperature with an optional temperature in degrees Celsius.[29][30]

Within the unregulated sector, such as journalism, the use of Fahrenheit in the United Kingdom follows no fixed pattern with degrees Fahrenheit often appearing alongside degrees Celsius. The Daily Mail, on its daily weather page, quotes Celsius first, followed by Fahrenheit in brackets,[31] The Daily Telegraph does not mention Fahrenheit on its daily weather page[32] while The Times also has an all-metric daily weather page but has a Celsius-to-Fahrenheit conversion table.[33] When publishing news stories, much of the UK press have adopted a tendency of using degrees Celsius in headlines and discussion relating to low temperatures and Fahrenheit for high temperatures.[34] In February 2006, the writer of an article in The Times suggested that the rationale was one of emphasis: "−6 °C" sounds colder than "21 °F" and "94 °F" sounds more impressive than "34 °C".[35]

Unicode representation of symbol

Unicode provides the Fahrenheit symbol at code point U+2109 ℉ DEGREE FAHRENHEIT. However, this is a compatibility character encoded for roundtrip compatibility with legacy encodings. The Unicode standard explicitly discourages the use of this character: "The sequence U+00B0 ° DEGREE SIGN +U+0046 F LATIN CAPITAL LETTER F is preferred over U+2109 ℉ DEGREE FAHRENHEIT, and those two sequences should be treated as identical for searching."[36]

See also

- Comparison of temperature scales

- Degree of frost

Notes and references

- Robert T. Balmer (2010). Modern Engineering Thermodynamics. Academic Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-12-374996-3. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Fahrenheit temperature scale, Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 25 September 2015

- "Fahrenheit: Facts, History & Conversion Formulas". Live Science. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- http://metricviews.org.uk/2012/10/50-years-of-celsius-weather-forecasts-%E2%80%93-time-to-kill-off-fahrenheit-for-good/

- Walt Boyes (2009). Instrumentation Reference Book. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-7506-8308-1. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Preston–Thomas, H. (1990). "The International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90)" (PDF). Metrologia. 27 (1): 6. Bibcode:1990Metro..27....3P. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/27/1/002. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Grigull, Ulrich (1966). Fahrenheit, a Pioneer of Exact Thermometry. (The Proceedings of the 8th International Heat Transfer Conference, San Francisco, 1966, Vol. 1, pp. 9–18.)

- Grigull, Ulrich (1966). Fahrenheit, a Pioneer of Exact Thermometry. (The Proceedings of the 8th International Heat Transfer Conference, San Francisco, 1966, Vol. 1, pp. 9–18.)

- Knake, Maria (April 2011). "The Anatomy of a Liquid-in-Glass Thermometer". AASHTO re:source, formerly AMRL (aashtoresource.org). Retrieved 4 August 2018.

For decades mercury thermometers were a mainstay in many testing laboratories. If used properly and calibrated correctly, certain types of mercury thermometers can be incredibly accurate. Mercury thermometers can be used in temperatures ranging from about -38 to 350°C. The use of a mercury-thallium mixture can extend the low-temperature usability of mercury thermometers to -56°C. (...) Nevertheless, few liquids have been found to mimic the thermometric properties of mercury in repeatability and accuracy of temperature measurement. Toxic though it may be, when it comes to LiG [Liquid-in-Glass] thermometers, mercury is still hard to beat.

- "Sal Armoniac" was an impure form of ammonium chloride. The French chemist Nicolas Lémery (1645–1715) discussed it in his book Cours de Chymie (A Course of Chemistry, 1675), describing where it occurs naturally and how it can be prepared artificially. It occurs naturally in the deserts of northern Africa, where it forms from puddles of animal urine. It can be prepared artificially by boiling 5 parts of urine, 1 part of sea salt, and ½ part of chimney soot until the mixture has dried. The mixture is then heated in a sublimation pot until it sublimates ; the sublimated crystals are sal Armoniac. See:

- Nicolas Lémery, Cours de chymie … , 7th ed. (Paris, France: Estienne Michallet, 1688), Chapitre XVII: du Sel Armoniac, pp. 338–339.

- English translation: Nicolas Lémery with James Keill, trans., A Course of Chymistry … , 3rd ed. (London, England: Walter Kettilby, 1698), Chap. XVII: of Sal Armoniack, p. 383. Available on-line at: Heinrich Heine University (Düsseldorf, Germany)

- Fahrenheit, Daniele Gabr. (1724) Experimenta & observationes de congelatione aquæ in vacuo factæ a D. G. Fahrenheit, R. S. S (Experiments and observations on water freezing in the void by D. G. Fahrenheit, R. S. S.), Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 33, no. 382, page 78 (March–April 1724). Cited and translated in http://www.sizes.com:80/units/temperature_Fahrenheit.htm

- "Wetterlexikon - Lufttemperatur" (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- Ernst Cohen and W.A.T. Cohen-De Meester. Chemisch Weekblad, volume 33 (1936), pages 374–393, cited and translated in http://www.sizes.com:80/units/temperature_Fahrenheit.htm

- Frautschi, Steven C.; Richard P. Olenick; Tom M. Apostol; David L. Goodstein (14 January 2008). The mechanical universe: mechanics and heat. Cambridge University Press. p. 502. ISBN 978-0-521-71590-4.

- Cecil Adams (15 December 1989). "On the Fahrenheit scale, do 0 and 100 have any special significance?". The Straight Dope.

- Fahrenheit, Daniele Gabr. (1724) "Experimenta circa gradum caloris liquorum nonnullorum ebullientium instituta" Archived 29 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Experiments performed concerning the degree of heat of some boiling liquids), Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 33 : 1–3. For an English translation, see: Le Moyne College (Syracuse, New York)

- Hasok Chang, Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress, pp. 8–11, Oxford University Press, 2004 ISBN 0198038240.

- Elert, Glenn; Forsberg, C; Wahren, LK (2002). "Temperature of a Healthy Human (Body Temperature)". Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 16 (2): 122–8. doi:10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00069.x. PMID 12000664. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Eutectic temperature of ammonium chloride and water is listed as −15.9 °C (3.38 °F) and as −15.4 °C (4.28 °F) in (respectively)

- Peppin SS, Huppert HE, Worster MG (2008). "Steady-state solidification of aqueous ammonium chloride" (PDF). J. Fluid Mech. Cambridge University Press. 599: 472 (table 1). doi:10.1017/S0022112008000219.

- Barman N, Nayak AK, Chattopadhyay H (2014). "Solidification of a Binary Solution (NH4Cl+H2O) on an Inclined Cooling Plate: A Parametric Study" (PDF). Procedia Materials Science. 5: 456 (table 1). doi:10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.288.

- "782 - Aerodrome reports and forecasts: A user's handbook to the codes". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- Halsey, Frederick A., Dale, Samuel S. (1919). The metric fallacy (2 ed.). The American Institute of Weights and Measures. pp. 165–166, 176–177. Retrieved 19 May 2009.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Canadian Units of Measurement; Department of Justice, Weights and Measures Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. W-6)". 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Pearlstein, Steven (4 June 2000). "Did Canada go metric? Yes - and no". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "Example of analog thermometer frequently used in Canada". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "Example of digital thermometer frequently used in Canada". Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- Department of Justice (26 February 2009). "Canadian Weights and Measures Act". Federal Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Statutory Instrument 2009/3046 - Weights and Measures - The Units of Measurement Regulations 2009 (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2017,

"The Secretary of State, being a Minister designated(a) for the purposes of section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972(b) in relation to units of measurement to be used for economic, health, safety, or administrative purposes, in exercise of the powers conferred by that subsection, makes the following Regulations:

- "Home Laundering Consultative Council - What Symbols Mean". Home Laundering Consultative Council. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Guide to Common Home Laundering & Drycleaning Symbols". Textile Industry Affairs. 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Guide to Apparel and Textile Care Symbols". Office of Consumer Affairs, Government of Canada. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Weather". The Daily Mail. 3 July 2013. p. 3.

- "Weather". The Daily Telegraph. 3 July 2013. p. 31.

- "Weather". The Times. 3 July 2013. p. 55.

- Roy Greenslade (29 May 2014). "Newspapers run hot and cold over Celsius and Fahrenheit". The Guardian.

- "Measure for measure". The Times. Times Newspapers. 23 February 2006.

- "22.2". The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0 (PDF). Mountain View, CA, USA: The Unicode Consortium. August 2015. ISBN 978-1-936213-10-8. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

External links

| Look up fahrenheit in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (Polish-born Dutch physicist) – Encyclopædia Britannica

- "At Auction | One of Only Three Original Fahrenheit Thermometers" Enfilade page for 2012 Christie's sale of a Fahrenheit mercury thermometer with some nice pictures

- "SI Units - Temperature". nist.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology (US Department of Commerce). 15 November 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2020.