Economy of Lithuania

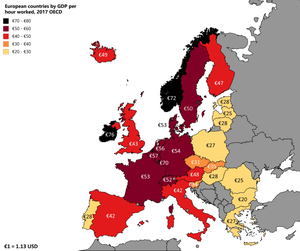

The economy of Lithuania is the largest economy among the three Baltic states. Lithuania is a member of the European Union and its GDP per capita is the highest in the Baltic states.[26] Lithuania belongs to the group of very high human development countries and is a member of WTO and OECD.

Vilnius downtown | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, WTO, OECD |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | €1,381 / $1,580 monthly (Q1, 2020) |

Average net salary | €879 / $1,006 monthly (Q1, 2020) |

Main industries | Petroleum refining, food processing, energy supplies, chemicals, furniture, wood products, textile and clothing[17] |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | Refined fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals, textiles, foodstuffs, plastics[14] |

Main export partners | |

| Imports | |

Import goods | Oil, natural gas, machinery and equipment, transport equipment, chemicals, textiles and clothing, metals[14] |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | 35.2% of GDP (2019)[19] |

| Expenses | 34.9% of GDP (2019)[19] |

| Economic aid | EU structural assistance: €8.4 billion(~$10 billion) 2014–2020[20] |

Foreign reserves | |

Lithuania was the first country to declare independence from Soviet Union in 1990 and rapidly moved from centrally planned to a market economy, implementing numerous liberal reforms. It enjoyed high growth rates after joining the European Union along with the other Baltic states, leading to the notion of a Baltic Tiger. Lithuania's economy (GDP) grew more than 500 percent since regaining independence in 1990. Half of the workforce in the Baltic states – 3.3 million live in Lithuania – 1.4 million.

GDP growth reached its peak in 2008, and is approaching the same levels again in 2018.[27] Similar to the other Baltic States, the Lithuanian economy suffered a deep recession in 2009, with GDP falling by almost 15%. After severe recession, the country's economy started to show signs of recovery already in 3rd quarter of 2009, returned to growth in 2010 with positive 1.3 outcome and with 6.6 per cent growth during the first half of 2011 country is one of the fastest growing economies in the EU.[28] GDP growth has resumed in 2010, albeit at a slower pace than before the crisis.[29][30] Success of the crisis taming is attributed to the austerity policy of the Lithuanian Government.[31]

Lithuania has a sound fiscal position. The 2017 budget resulted in a 0.5% surplus, the gross debt is stabilising at around 40% of GDP. The budget remained positive in 2017 and is expected so in 2018.[32]

Lithuania is ranked 11th in the world in the Ease of Doing Business Index prepared by the World Bank Group[33] and 16th out of 178 countries in the Index of Economic Freedom, measured by The Heritage Foundation.[34] On average, more than 95% of all foreign direct investment in Lithuania comes from European Union countries. Sweden is historically the largest investor with 20% – 30% of all FDI in Lithuania.[35] FDI into Lithuania spiked in 2017, reaching its highest ever recorded number of greenfield investment projects. In 2017, Lithuania was third country, after Ireland and Singapore by the average job value of investment projects.[36]

Based on OECD data, Lithuania is among the top 5 countries in the world by postsecondary (tertiary) education attainment.[37] Educated workforce attracted investments especially in ICT sector during the past years. The Lithuanian government and the Bank of Lithuania simplified procedures for obtaining licences for the activities of e-money and payment institutions.[38] positioning the country as one of the most attractive for the FinTech initiatives in EU.

History of economy

The history of Lithuania can be divided into seven major periods. All the periods have some interesting and important facts that affected the economic situation of the country in those times.

- Ancient times – Baltic tribes (until the 13th century)

- Kingdom of Lithuania (1251–1263)

- Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1263–1569)

- Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

- Pressure of the Russian Empire (1795–1914)

- Republic of Lithuania during the interwar period (1918–1940)

- Soviet occupied Lithuania (1944–1990)

- Republic of Lithuania (1990–)

History up to the 20th century

The first Lithuanians formed a branch of an ancient ethno-linguistic group known as the Balts. Lithuanian tribes maintained close trade contacts with the Roman Empire.[39] Amber was the main good provided to the Roman Empire from Baltic Sea coast, via a long route called the Amber Road.

Consolidation of the Lithuanian lands began in the late 12th century. King Mindaugas was the first pan-Lithuanian ruler, as the Catholic King of Lithuania in 1253. The expansion of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania reached its height in the middle of the 14th century under the Grand Duke Gediminas (reigned 1316–1341), who established a strong central government which later came to dominate the territories from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Grand Duke Gediminas issued letters to the Hanseatic league, offering free access to his domains for men of every order and profession from nobles and knights to tillers of the soil. Economic immigrants and immigrants, seeking religious freedom improved the level of handicrafts. During the reign of Duke Kęstutis (1297–1382), the first cash taxes were introduced, although most taxes were still paid in goods (e.g., wheat, cattle, horses).

In 1569 the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth formed through the union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The economy of the Commonwealth was dominated by feudal agriculture based on the exploitation of the agricultural workforce (serfs). Poland-Lithuania played a significant role in supplying 16th-century Western Europe with exports of three sorts of goods: grain (rye), cattle (oxen) and fur. These three articles amounted to nearly 90% of the country's exports to western markets by overland and maritime trade. There was even a Lithuanian trading vessel – vytinė, used for four hundred years to transport grain via Nemunas river. Statutes of Lithuania were the main collections of law statements and rules in Lithuania.

The Commonwealth was famous for Europe's first and the world's second modern codified national constitution, the so-called Constitution of 3 May, declared on 3 May 1791 (after the 1788 ratification of the United States Constitution). Economic and commercial reforms, previously shunned as unimportant by the Szlachta, were introduced, and the development of industries was encouraged.

Following the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793 and 1795, the Russian Empire controlled the majority of Lithuania. During the administration of the Lithuanian lands by the Russian Empire from 1772 to 1917, one of the most important events that affected economic relations was the emancipation reform of 1861 in Russia. The reform amounted to the liquidation of serf dependence previously suffered by peasants; it boosted the development of capitalism.

Lithuania in the 20th century

On 16 February 1918, the Council of Lithuania passed a resolution for the re-establishment of the Independent State of Lithuania. Soon, many economic reforms for sustainable economic growth were implemented. A national currency, called the Lithuanian litas, was introduced in 1922. It proved to become one of the strongest and most stable currencies in Europe during the inter-war period.[40] Lithuania had a monometalism system where one litas was covered by 0.150462 grams of gold stored by the Bank of Lithuania in foreign countries. Litas remained stable even in the period of Great Depression. During the time of its independence, 1918–1940, Lithuania made substantial progress. For example, Lithuania was the third-ranking flax producer and exporter in the world market (export of flax constituted about 30 percent of all export share[41]), being surpassed only by Soviet Russia and Poland;[42] Lithuanian farm products such as meat, dairy products, many kinds of grain, potatoes, etc. were of superior quality in the world market. Lithuanian farmers were joining into cooperative companies – e.g. Lietūkis, Pienocentras, Linas, which helped farmers to process and sell their products more efficiently and profitably.

Having taken advantage of favorable international developments, and driven by its foreign policy aims directed against Lithuanian statehood, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) occupied Lithuania in 1940.[43] Land and the most important objects for the economy were nationalized, and most of the farms collectivized. Just after one year of occupation, poverty level, uneployment increased dramatically, lack of food products appeared. Later, many inefficient factories and industry companies, highly dependent on other regions of USSR, were established in Lithuania. Despite that, in 1990, GDP per capita of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was $8,591, which was above the average for the rest of the Soviet Union of $6,871 but lagging behind developed western countries.

The Soviet era brought Lithuania intensive industrialization and economic integration into the USSR, although the level of technology and state concern for environmental, health, and labor issues lagged far behind Western standards.[44] Urbanization increased from 39% in 1959 to 68% in 1989. From 1949 to 1952 the Soviets abolished private ownership in agriculture, establishing collective and state farms. Production declined and did not reach pre-war levels until the early 1960s. The intensification of agricultural production through intense chemical use and mechanization eventually doubled production but created additional ecological problems. This changed after independence, when farm production dropped due to difficulties in restructuring the agricultural sector.[44]

The overall damage, resulted from the Soviet occupation (including the loss of gross domestic product), estimated according to the UN recognised methodologies amounted to approximately US$800 billion; direct damage (including genocide and deportations of the citizens, property looting) estimation is US$20 billion.[45]

According to a 2019 study by economic historians, Lithuania had above average economic growth from 1937 to 1973 (when compared to other economies), but below average growth from 1973 to 1990.[46]

Development since the 1990s

Reforms since the mid-1990s led to an open and rapidly growing economy. Open to global trade and investment, Lithuania now enjoys high degrees of business, fiscal, and financial freedom. Lithuania is a member of the EU and the WTO, so regulation is relatively transparent and efficient, with foreign and domestic capital subject to the same rules. The financial sector is advanced, regionally integrated, and subject to few intrusive regulations.[34]

One of Lithuania's most important reforms was the privatization of state-owned assets. The first stage of privatization was being implemented between 1991 and 1995. Citizens were given investment vouchers worth €3.1 billion in nominal value, which let them participate in assets selling.[47] By October 1995, they were used as follows: 65% for acquisition of shares; 19% for residential dwellings; 5% for agricultural properties; and 7% remained unused.[47] More than 5,700 enterprises with €2.0 billion worth of state capital in book value were sold using four initial privatization methods: share offerings; auctions; best business plans competitions; and hard currency sales.[47]

The second privatization step began in 1995 by approving a new law that ensured greater diversity of privatization methods and that enabled participation in the selling process without vouchers. Between 1996 and 1998, 526 entities were sold for more than €0.7 billion.[47] Before the reforms, the public sector totally dominated the economy, whereas the share of the private sector in GDP increased to over 70% by the 2000 and 80% in 2011.[48]

Monetary reform was undertaken in early nineties to improve the stability of the economy. Lithuania chose a currency board system controlled by the Bank of Lithuania independent of any government institution. On 25 June 1993, the Lithuanian litas was introduced as a freely convertible currency, but on 1 April 1994 it was pegged to the United States dollar at a rate of 4 to 1. The mechanism of the currency board system enabled Lithuania to stabilize inflation rates to single digits. The stable currency rate helped to establish foreign economic relations, therefore leading to a constant growth of foreign trade.[49]

By 1998, the economy had survived the early years of uncertainty and several setbacks, including a banking crisis. However, the collapse of the Russian ruble in August 1998 shocked the economy into negative growth and forced the reorientation of trade from Russia towards the West.[44]

Lithuania was invited to the Helsinki EU summit in December 1999 to begin EU accession talks in early 2000.[50]

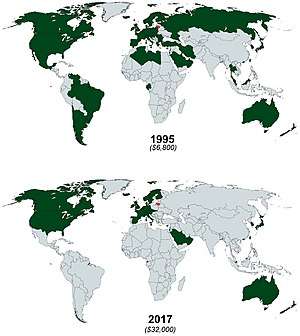

After the Russian financial crisis, the focus of Lithuania's export markets shifted from East to West. In 1997, exports to the Soviet Union's successor entity (the Commonwealth of Independent States) made up 45% of total Lithuanian exports. This share of exports dropped to 21% of the total in 2006, while exports to EU members increased to 63% of the total.[44] Exports to the United States made up 4.3% of all Lithuania's exports in 2006, and imports from the United States comprised 2% of total imports. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2005 was €0.8 billion.

On 2 February 2002 the litas was pegged to the euro at a rate of 3.4528 to 1, which remained until Lithuania adopted the euro in 2015. Lithuania was very close to introducing the euro in 2007, but the inflation level exceeded the Maastricht requirements.[51] On 1 January 2015, Lithuania became the 19th country to use the euro.[52]

The Vilnius Stock Exchange, now renamed the NASDAQ OMX Vilnius, started its activity in 1993 and was the first stock exchange in the Baltic states. In 2003, the VSE was acquired by OMX. Since 27 February 2008 the Vilnius Stock Exchange has been a member of NASDAQ OMX Group, which is the world's largest exchange company across six continents, with over 3,800 listed companies.[53] The market cap of Vilnius Stock Exchange was €3.4 billion on 27 November 2009.[54]

During the last decade (1998–2008) the structure of Lithuania's economy has changed significantly. The biggest changes were recorded in the agricultural sector as the share of total employment decreased from 19.2% in 1998 to just 7.9% in 2008. The service sector plays an increasingly important role. The share of GDP in financial intermediation and real estate sectors was 17% in 2008 compared to 11% in 1998. The share of total employment in the financial sector in 2008 has doubled compared with 1998.[55][56]

Lithuania in the 21st century

Between 2000 and 2017, the Lithuanian GDP grew by 308%.[57]

One of the most important factors contributing to Lithuania's economic growth was its accession to the WTO in 2001 and the EU in 2004, which allows free movement of labour, capital, and trade among EU member states. On the other hand, rapid growth caused some imbalances in inflation and balance of payments. The current account deficit to GDP ratio in 2006–2008 was in the double digits and reached its peak in the first quarter of 2008 at a threatening 18.8%.[58] This was mostly due to rapid loan portfolio growth as Scandinavian banks provided cheap credit under quite lax rules in Lithuania. The volume of loans to acquire lodgings has grown from 50 million LTL in 2004 up to 720 million LTL in 2007.[59] Consumption was affected by credit expansion as well. This led to high inflation of goods and services, as well as trade deficit. A housing bubble was formed.

The global credit crunch which started in 2008 affected the real estate and retail sectors. The construction sector shrank by 46.8% during the first three-quarters of 2009 and the slump in retail trade was almost 30%.[29][60] GDP plunged by 15.7% in the first nine months of 2009.[29]

Lithuania was the last among the Baltic states to be hit by recession because its GDP growth rate in 2008 was still positive, followed by a slump of more than 15% in 2009. In the third quarter of 2009, compared to the previous quarter, GDP again grew by 6.1% after five-quarters with negative numbers.[29] Austerity policy (four-fifths of the fiscal adjustment consisted of expenditure cuts)[61] introduced by the Kubilius government helped to balance the current account from −15.5 in 2007 to 1.6 in 2009.[62] Economic sentiment and confidence of all business activities have rebounded from a record low at the beginning of the year 2009.

Sectors related to domestic consumption and real estate still suffer from the economic crisis, but exporters have started making profits even with lower levels of revenue. The catalysts of growing profit margins are lower raw material prices and staff expense.

At the end of 2017, investment of Lithuania's enterprises abroad amounted to EUR 2.9 billion. The largest investment was made in Netherlands (24.1 per cent of the total direct investment abroad), Cyprus (19.8 per cent), Latvia (14.9 per cent), Poland (10.5 per cent) and Estonia (10.3 per cent). Lithuania's direct investment in the EU member states totalled EUR 2.6 billion, or 89.3 per cent of the total direct investment abroad.[63]

Based on the Eurostat's data, in 2017, the value of Lithuanian exports recorded the most rapid growth not only in the Baltic countries, but also across Europe, which was 16.9 per cent.[64] Lithuania performs well in few measures of well-being in the Better Life Index by OECD, ranking above the average in education and skills, and work-life balance. It is below the average in income and wealth, jobs and earnings, housing, health status, social connections, civic engagement, environmental quality, personal security, and subjective well-being.[65] Lithuanian people are the happiest people in the Baltic States.[66][67]

Euro adoption

On 1 January 2015, Lithuania became the 19th country to adopt the euro. Joining the euro would relieve the Bank of Lithuania of defending the value of the litas, and "it would give Lithuania a say in the decision-making of the European Central Bank (ECB), as well as access to the ECB single-resolution fund and cheaper borrowing costs".[52]

Business climate

Cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2017 was EUR 14.7 billion, or 35 per cent of GDP, EUR 5215 per capita.[68] The largest FDI flow in Lithuania was into manufacturing (EUR 73.7 million), agriculture, forestry, fishery (EUR 27.4 million), information and communication (EUR 10 million). Sweden, The Netherlands and Germany have remained the largest investors.[68]

Lithuania seeks to become an innovation hub by 2020. To reach this goal, it is putting its efforts into attracting FDI to added-value sectors, especially IT services, software development, consulting, finance, and logistics.[69] Well-known international companies such as Microsoft, IBM, Transcom, Barclays, Siemens, SEB, TeliaSonera, Paroc, Wix.com, Philip Morris, Thermo Fisher Scientific established a presence in Lithuania.

Lithuanian FEZs (Free economic zone) offer developed infrastructure, service support, and tax incentives. A company set up in an FEZ is exempt from corporate taxation for its first six years, as well as a tax on dividends and real estate tax.[70] 7 FEZ operate in Lithuania – Marijampolė Free Economic Zone, Kaunas Free Economic Zone, Klaipėda Free Economic Zone, Panevėžys Free Economic Zone, Akmenė Free Economic Zone, Šiauliai Free Economic Zone, Kėdainiai Free Economic Zone. There are nine industrial sites in Lithuania, which can also provide additional advantages by having a well-developed infrastructure, offering consultancy service and tax incentives.[71] Lithuania is ranked third among developed economies by the quantity (16) of Special Economic Zones – after USA (256) and Poland (21).[72]

Lithuanian municipalities provide special incentives to investors who create jobs or invest in infrastructure. Municipalities may tie designation criteria to additional factors, such as the number of jobs created or environmental benefits. Strategic investors' benefits could include favorable tax incentives for up to ten years. Municipalities may grant special incentives to induce investments in municipal infrastructure, manufacturing, and services.[73]

About 40 percent of surveyed investors confirmed that they carrying out Research and experimental development (R&D) or plan to do it in their Lithuanian branches.[74] In 2018 Lithuania ranked as the second most attractive location for manufacturers in the Manufacturing Risk Index 2018.[75] In 2019, Lithuania was 16th in Top 20 European FDI destination countries list, created by the Ernst & Young.[76]

Corporations

Lithuania traditionally has strong agricultural, furniture, logistics, textile, biotechnology and laser industries. Maxima is a retail chain operating in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland and Bulgaria and it is the largest Lithuanian capital company and the largest employer in the Baltic states. Girteka Logistics is a largest Europe's transport company. Biotechpharma is a biopharmaceutical research and development company with a focus on recombinant protein technology development. The BIOK Laboratory is a startup founded by biochemistry scientists which is the biggest producer of Lithuanian natural cosmetic products. UAB SANITEX is the largest wholesale, distribution and logistics company in Lithuania and Latvia, also active in Estonia and Poland. UAB SoliTek Cells – leading producer of solar cells in Northern Europe. One of the leaders of cellular IoT gateways producers in Europe – UAB Teltonika.

In the "Baltic Top 50", the biggest Baltic states companies rating created by Coface, more than half – 29 – companies are from Lithuania.[77]

Workforce

The number of the population aged 15 years and over is 1.45 million, activity rate was 60 percent in 2017.[79]

During the period of 1995–2017 average salary grew more than four times in Lithuania.[80] Despite this, labour costs in Lithuania are among the lowest in the EU. Average monthly net salary in IV quarter 2018 was EUR 800 and increased by 9.5 percent. Unemployment in Lithuania has been volatile. Since the year 2001, the unemployment rate has decreased from almost 20% to less than 4% in 2007 thanks to two main reasons. Firstly, during the time of rapid economic expansion, numerous work places were established. This caused a decrease in the unemployment rate and a rise in staff expenses. Secondly, emigration has also reduced unemployment problems since accession to the EU. However, the economic crisis of year 2008 has lowered the need for workers, so the unemployment rate increased to 13.8% and then stabilized in the third quarter of 2009. Unemployment rate in I quarter of 2018 was 6.3 percent.[81]

Lithuania is among the top 5 countries in the world by postsecondary (tertiary) education attainment.[37]As of 2016, 54.9% of the population aged 25 to 34, and 30.7% of the population aged 55 to 64 had completed tertiary education.[82] The share of tertiary-educated 25–64-year-olds in STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields in Lithuania were above the OECD average (29% and 26% respectively), similarly to business, administration and law (25% and 23% respectively).[83]

The level of labour productivity in Lithuania today is about one-third below the OECD average.[84] Lithuania is ranked 15th in Employment Flexibility Index.[85]

Income and wealth distribution

Lithuania belongs to high income group according to Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2019.[86] As of 2019, Lithuanian average wealth per adult was $50,254 (an increase of 82% from $27,507 in the year 2017) [87] Household debt is among the lowest among EU countries – 49 percent of net disposable income in 2015.[88]

Sectors of economy

Services

One of the most important sub-sectors is information and communication technologies (ICT). Around 37,000 employees work for more than 2,000 ICT companies. ICT received 9.5% of total FDI. Lithuania hosts 13 of the 20 largest IT companies in the Baltic States.[89] Lithuania exported EUR 128 million worth ICT services in II quarter of 2018.

Development of shared services and business process outsourcing are some of the most promising fields. Companies that have outsourced their business operations to Lithuania include Barclays, Danske Bank, CITCO Group, Western Union, Uber, MIRROR, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Anthill, Adform, Booking Holdings (Kayak.com, Booking.com), HomeToGo, Visma, Unity, Yara International, Nasdaq Nordic, Bentley Systems, Ernst & Young and many more.

Financial services

_(7692990530).jpg)

The financial sector concentrates mostly on the domestic market. There are nine commercial banks that hold a license from the Bank of Lithuania and eight foreign bank branches.[90] Most of the banks belong to international corporations, mainly Scandinavian. The financial sector has demonstrated incredible growth in the pre-crisis period (1998–2008). Bank assets were only €3.2 billion or 25.5% from GDP in 2000, half of which consisted of loan portfolio.[91]

By the beginning of the year 2009, bank assets grew to €26.0 billion or 80.8% to GDP, the loan portfolio reached €20.7 billion.[92] The loan-to-GDP ratio was 64%. The growth of deposits was not as fast as that of loans. At the end of 2008, the loan portfolio was almost twice as big as that of deposits. It demonstrated high dependence on external financing. Contraction in the loan portfolio has been recorded over the past year, so the loans to deposits ratio are slowly getting back to healthy levels.

FinTech

The country has increasingly sought position itself as the EU's main fintech hub, hoping to attract international firms by promising to provide European operational licences within three months, compared to a waiting period of up to a year in countries like Germany or the UK.[93] In 2017 only, 35[94] FinTech companies came to Lithuania – a result of Lithuanian government and Bank of Lithuania simplified procedures for obtaining licences for the activities of e-money and payment institutions.[38] Europe's first international Blockchain Centre launched in Vilnius in 2018.[95] The government of Lithuania also aims to attract financial institutions looking for a new location after Brexit.[96][97] Lithuania has granted a total of 39 e-money licenses, second in the EU only to the U.K. with 128 licenses. In 2018, Google set up a payment company in Lithuania,[98] Vilnius was ranked a seventh FinTech city by foreign direct investment (FDI) performance in 2019.[99]

Central Bank of Lithuania established a Regulatory sandbox[100] to test financial innovations in a live environment under the guidance and supervision of the Bank of Lithuania. Bank of Lithuania has also developed LBChain which is the world's first blockchain-based sandbox developed by a financial market regulator, combining technological and regulatory infrastructures.[101]

Moody's Corporation declared about opening its office in Vilnius.[102]

Manufacturing

Lithuania has a much larger manufacturing sector share in the economy’s structure than the other Baltic countries. In this regards Lithuania is closer to some Central European countries like Czech Republic or Germany.[103]

Manufacturing constitutes the biggest part of gross value added in Lithuania. The food processing sector constitutes 11% of total exports. Dairy products, especially cheese, are well known in neighbouring countries. Another important manufacturing activity is chemical products. The manufacturing of machinery and equipment sector in Lithuania comprises 7.1% of the country’s GDP. 80% of production is exported so chemical products constitute 12.5% of total exports. Year 2019 was exemplary – more than 10 new factories were opened in Lithuania, working in the fields in engineering, high precision instruments, furniture and medical products.

- Furniture

Furniture production employs more than 50,000 people and has seen double-digit growth over the last three years. The biggest companies in this field work in cooperation with IKEA, which owns one of the biggest wood processing companies in Lithuania. Lithuania is the fourth biggest supplier of furniture for IKEA after Poland, Italy and Germany.[104]

- Automotive industry

Continental AG in 2018 started to build a factory for high precision car electronics – biggest greenfield investment project in Lithuania so far.[105] Another German manufacturer of lighting technology Hella opened a plant in 2018 in Kaunas FEZ, which will produce sensors, actuators and control modules for automotive industry.[106] Lithuania's automotive cluster experienced significant growth during the past 5 years.

Companies in the automotive and engineering sector are relatively small but offer flexible services for small and non-standard orders at competitive prices. The sector employs about 3% of the working population and receives 5.6% of FDI.[107] Vilnius Gediminas Technical University prepares experts for the sector.

- Biotechnology and life sciences

Lithuania's life science sector is growing around 20–25% annually; with special focus on the production and research of biotechnology, pharmaceutical and medical devices.[108]

- Laser technology

Lithuanian laser companies were among the first ones in the world to transfer fundamental research into manufacturing. Lithuania's laser producers export laser technologies and devices to nearly 100 countries. Half of all picosecond lasers sold worldwide are produced by Lithuanian companies, while Lithuanian-made femtosecond parametric light amplifiers, used in generating the ultrashort laser pulses, account for as much as 80% of the world market.[109]

Tourism

Tourism in Lithuania becoming increasingly important for local economy, constituting around 5.3% of GDP in 2016.[110] Lithuania has 22,000 rivers and rivulets, 3,000 lakes, a well-developed rural tourism network, a unique coastal area of almost 100 km and four UNESCO World Heritage sites. Lithuania receives more than 1.4 million foreign tourists a year.[111] Germany, Poland, Russia, Latvia, and Belarus supply the most tourists, and a significant number arrive from the UK, Finland, and Italy as well.

Agriculture

Despite a decreased share in GDP, the agricultural sector is still important for Lithuania as it employs almost 8% of the work force and supplies materials for the food processing sector. 44.8% of the land is arable.[112] Total crop area was 1.8 million hectares in 2008.[113] Cereals, wheat, and triticale are the most popular production of farms. The number of livestock and poultry has decreased twofold compared to the 1990s. The number of cattle in Lithuania at the beginning of the year 2009 was 770,000, the number of dairy cows was 395,000, and the number of poultry was 9.1 million.[114]

Lithuanian food consumption has evolved; between 1992 and 2008, consumption of vegetables increased by 30% to 86 kg per capita, and consumption of meat and its products increased by 23% during the same period to 81 kg per capita.[115] On the other hand, consumption of milk and dairy products has decreased to 268 kg per capita by 21%, and the consumption of bread and grain products decreased to 114 kg per capita by 19% as well.[115]

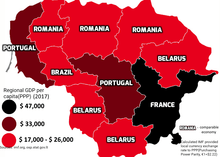

Regional situation

| County | Area (km²) | Population (thousands) in 2018[117] | Nominal GDP billions EUR in 2018[117] | Nominal GDP per capita EUR in 2018[117] | GDP PPP per capita USD in 2018[118][117] | Countries with comparable GDP PPP per capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alytus County | 5,425 | 137 | 1.3 | 9,800 | 21,100 | |

| Kaunas County | 8,089 | 562 | 9.4 | 15,200 | 32,700 | |

| Klaipėda County | 5,209 | 318 | 4.9 | 15,600 | 33,500 | |

| Marijampolė County | 4,463 | 140 | 1.3 | 9,400 | 20,200 | |

| Panevėžys County | 7,881 | 222 | 2.6 | 11,800 | 25,400 | |

| Šiauliai County | 8,540 | 264 | 3.2 | 12,200 | 26,200 | |

| Tauragė County | 4,411 | 95 | 0.9 | 9,100 | 19,600 | |

| Telšiai County | 4,350 | 136 | 1.5 | 11,600 | 24,900 | |

| Utena County | 7,201 | 128 | 1.2 | 9,300 | 20,000 | |

| Vilnius County | 9,729 | 808 | 18.9 | 23,400 | 50,300 | |

| Lithuania | 65,300 | 2,800 | 45.3 | 16,200 | 34,800 |

Lithuania is divided into ten counties. There are four cities with a population over 100,000 and four cities of over 30,000 people. The gross regional product is concentrated in the three largest counties – Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda. These three counties account for 70% of the GDP with just 60% of the population.[119] Service centers and industry are concentrated there. In five counties (those of Alytus, Marijampolė, Panevėžys, Šiauliai and Tauragė), GDP per capita is still below 80% of the national average.[119]

In order to achieve balanced regional distribution of GDP, nine public industrial parks (Akmene Industrial Park, Alytus Industrial Park, Kedainiai Industrial Park, Marijampolė Industrial Park, Pagegiai Industrial Park, Panevėžys Industrial Park, Radviliskis Industrial Park, Ramygala Industrial Park and Šiauliai Industrial Park) and three private industrial parks (Tauragė Private Industrial Park, Sitkunai Private Industrial Park, Ramučiai Private Logistic and Industrial Park) were established to provide some tax incentives and prepared physical infrastructure.[71]

Infrastructure

The transport, storage, and communication sector has increased its importance to the economy of Lithuania. In 2008, it accounted for 12.1% of GDP compared to 9.1% in 1996.[120]

Communications

Lithuania has a broadly developed radio, television, landline and mobile phone, as well as broadband internet networks.

Lithuanian National Radio and Television, the public broadcaster in Lithuania operates 3 television channels, including a satellite channel, as well as 3 radio stations. Privately owned commercial TV and Radio broadcasters operate a multitude national, regional and local channels.[121]

There are four TIER III datacenters in Lithuania.[122] Lithuania is 44th globally ranked country on data center density according to Cloudscene.[123]

The fixed landline network connects 625 thousand households and businesses (down from the record 845 thousand in 2005).[124] The decline in subscription and utilization of the landline network has been driven by increased availability of mobile phone services. The mobile telephony penetration rate in Lithuania (of 151 per 100 population in 2013) has been one of the highest in the world.[125] In 2013, there were 13 providers of mobile phone services, with the three largest ones – BITĖ Lietuva, Omnitel, and Tele2 – operating their own cellular networks.

Lithuanian retail internet sector is competitive, with more than 100 service providers. Retail internet connectivity in Lithuania was among the cheapest in Europe; however, the internet penetration rate (64% of households using internet in 2013) was lower than in other EU countries in the region – Estonia (79%), Latvia (70%) and Poland (69%). Lithuanian internet connection speeds have been claimed to be among the fastest in the world[126] based on user-initiated tests at Speedtest.net.

Energy

The utilities sector accounts for more than 3% of gross value added in Lithuania. Electricity production exceeded 12 billion kWh in 2007, and consumption exceeded 9.6 billion kWh. Surplus electricity is exported.

Lithuania operated a nuclear power plant in Visaginas, which produced 72% of electricity in Lithuania.[127] The plant was shut down on 31 December 2009 in line with the commitments made when Lithuania joined EU in 2004. New nuclear power plant in Visaginas has been proposed but the status of the project is uncertain after it was rejected by the voters in a referendum in 2012.

The supply of heating energy has been modernized during the last decade (1998–2008). Technological loss in the heat energy system has decreased significantly from 26.2% in the year 2000 to 16.7% in 2008. The amount of air pollution was reduced by one-third. The share of renewable energy resources in the total fuel balance for heat production increased to almost 20%.

In order to break down Gazprom's monopoly[128][129] in natural gas market of Lithuania, first large scale LNG import terminal (Klaipėda LNG FSRU) in the Baltic region was built in port of Klaipėda in 2014. The Klaipėda LNG terminal was called Independence, thus emphasising the aim to diversify energy market of Lithuania. Norvegian company Equinor supplies 540 million cubic metres (19 billion cubic feet) of natural gas annually from 2015 until 2020.[130] The terminal is able to meet the Lithuania's demand 100 percent, and Latvia's and Estonia's national demand 90 percent in the future.[131]

Kruonis Pumped Storage Plant operates as pumped-storage providing a spinning reserve of the power system, in order to regulate the load curve of the power system 24 hours a day. In 2015 Kruonis Industrial Park was established as a place for data centers.[132]

In 2018 synchronising the Baltic States' electricity grid with the Synchronous grid of Continental Europe has started.[133]

Transport

Lithuania forms part of the transport corridor between the East and the West. The volume of goods transported by road transport has increased fivefold since 1996. The total length of roadways is more than 80,000 km, and 90% of them are paved.[112] The government spending on road infrastructure exceeded €0.5 billion in 2008. Via Baltica highway passes through Kaunas, while membership in the Schengen Agreement allows for smooth border crossing to Poland and Latvia.

Railway transport in Lithuania provides long-distance passenger and cargo services. Railways carry approximately 50 million tons of cargo and 7 million passengers a year.[134] Direct rail routes link Lithuania with Russia, Belarus, Latvia, Poland, and Germany. Also, the main transit route between Russia and Russia's Kaliningrad Region passes through Lithuania. Lithuanian Railways AB transports about 44% of the freight carried through Lithuania.[135] This is a very high indicator compared to other EU countries, where freight transportation by rail amounts to only 10% of the total.[136]

An ice-free seaport of Klaipeda is located in the western part of Lithuania. The port is an important regional transport hub connecting the sea, land and railway routes from east and west. It handles roughly 7,000 ships and 30 million tons of cargo every year, and accepts large-tonnage vessels (dry-cargo vessels up to 70,000 DWT, tankers up to 100,000 DWT and cruise ships up to 270 meters long). The seaport of Klaipėda is able to receive Panamax-type vessels.[134] One of the fastest growing segments of sea transport is passenger traffic, which has increased fourfold since 2002. The inland river cargo port in Marvelė, linking Kaunas and Klaipėda, received first cargo in 2019.[137]

Lithuania has four international airports – Vilnius Airport (VNO), Kaunas Airport (KUN), Šiauliai Airport (SQQ) and Palanga Airport (PLQ). More than 30 domestic airports being used by aeroclubs and amateur pilots.

Storage

There are more than 600,000 m2 of modern logistics and warehousing facilities in Lithuania.[138] The biggest supply of new, modern warehousing facilities is in the capital city Vilnius (after the completion of several new projects in the third quarter of 2009, the supply of modern warehousing premises has increased by nearly 12% in Vilnius and currently reaches 334,400 m2 of the rentable area). Kaunas is in the second place (around 200,000 m2), and Klaipėda in the third (122,500 m2).[134] Since the beginning of the year 2009, prices for warehousing premises have dropped by 20–25% in Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda, and the current level of rents has reached the level of 2003.[138] The costs for renting new warehouses in Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda are similar and reach 0.75 to 1.42 EUR/m2, while the rents of old warehouses are 0.35 to 0.67 EUR/m2.

International trade

Lithuanian economy is highly open and International trade is crucial. As a result, the ratio of foreign trade to GDP for Lithuania has often exceeded 100%.

The EU is the biggest trade partner of Lithuania with a 67% of total imports and 61.3% of total exports during 2015.[139] The Commonwealth of Independent States is the second economic union that Lithuania trades the most with, with a share of imports of 25% and a share of exports of 23.9% during the same period.[139] The vast majority of commodities, including oil, gas, and metals have to be imported, mainly from Russia, however in the recent years Lithuania's energy dependence has shifted towards other countries such as Norway and the US. Mineral products constitute 25% of imports and 18% of exports, mainly driven by the presence of ORLEN Lietuva oil refinery with a refining capacity of 9 million tons a year, owned by Polish concern PKN Orlen.[140] Orlen Lietuva sold over €3.5 billion worth of products outside Lithuania,[140] compared to the total Lithuanian exports of €24 billion in 2014.

Some sectors are directed mainly at export markets. Transport and logistics export ⅔ of their products and/or services; the biotechnology industry exports 80%; plastics export 52%; laser technologies export 86%; metal processing, machinery and electric equipment export 64%; furniture and wood processing export 55%; textile and clothing export 76%; and the food industry exports 36%.[141]

| Country | Import | Country | Share of goods of Lithuanian origin in export | Export |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70.6% | 69.6% | 58.3% | ||

| 12.6% | 7.8% | 14.8% | ||

| 12.3% | 44.6% | 9.9% | ||

| 10.7% | 65.7% | 8.1% | ||

| 7.2% | 77.8% | 7.3% | ||

| 5.2% | 89.1% | 5.2% | ||

| 5.1% | 48.4% | 5.0% | ||

| 3.9% | 89.8% | 4.8% | ||

| 3.8% | 13.8% | 3.8% | ||

| 3.3% | 85.7% | 3.5% | ||

| 3.3% | 82.5% | 3.5% | ||

| 3.2% | 89.5% | 2.8% |

Natural resources

The total value of natural resources in Lithuania reached €17 billion, or half of Lithuania's GDP. The most valuable natural resource in the country is subterranean water, which constitutes more than half of the total value of natural resources.

Macro-economic

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1995–2017.[143]

| Year | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP in $ (PPP) |

24.63 Bln. | 33.66 Bln. | 54.56 Bln. | 60.40 Bln. | 68.89 Bln. | 72.08 Bln. | 61.87 Bln. | 63.65 Bln. | 68.90 Bln. | 72.85 Bln. | 76.72 Bln. | 80.75 Bln. | 83.29 Bln. | 86.33 Bln. | 91.24 Bln. |

| GDP per capita in $ (PPP) |

6,786 | 9,618 | 16,422 | 18,472 | 21,319 | 22,539 | 19,562 | 20,552 | 22,752 | 24,382 | 25,904 | 27,537 | 28,671 | 30,097 | 32,298 |

| GDP growth (real) |

... | 3.8% | 7.7% | 7.4% | 11.1% | 2.6% | −14.8% | 1.6% | 6.0% | 3.8% | 3.5% | 3.5% | 2.0% | 2.3% | 3.8% |

| Inflation (in percent) |

... | 1,0% | 2,7% | 3,8% | 5,8% | 11,2% | 4,2% | 1,2% | 4,1% | 3,2% | 1,2% | 0,2% | −0,7% | 0,7% | 3,7% |

| Unemployment rate (in percent) |

... | 16.4% | 8.3% | 5.8% | 4.2% | 5.8% | 13.8% | 17.8% | 15.4% | 13.4% | 11.8% | 10.7% | 9,1% | 7.9% | 7.1% |

| Government debt (percentage of GDP) |

... | 23% | 18% | 17% | 16% | 15% | 29% | 36% | 37% | 40% | 39% | 41% | 3% | 40% | 37% |

See also

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "The economic context of Lithuania". /www.nordeatrade.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

Agriculture contributes 3.3% to the GDP and employs 9.1% of the active workforce (CIA World Factbook 2017 estimates). Lithuania's main agricultural products are wheat, wood, barley, potatoes, sugar beets, wine and meat (beef, mutton and pork). The main industrial sectors are electronics, chemical products, machine tools, metal processing, construction material, household appliances, food processing, light industry (including textile), clothing and furniture. The country is also developing oil refineries and shipyards. The industrial sector contributes 28.5% to the GDP employing around 25% of the active population. Lastly, the services sector contributes 68.3% to the GDP and employs 65.8% of the active population. The information technology and communications sectors are the most important contributors to the GDP.

- "Compare your income - Perception of income inequality in OECD countries".

- "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Labor force, total – Lithuania". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Employment rate by sex, age group 20–64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Unemployment by sex and age – monthly average". appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Youth unemployment rate". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Pramonės produkcija, be PVM ir akcizo". Statistics Lithuania. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "Ease of Doing Business in Lithuania". Doingbusiness.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "Euro area and EU27 government deficit both at 0.6% of GDP" (PDF). ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Apie 2014–2020 m. ES fondų investicijas – Finansavimas – 2014–2020 Europos Sąjungos fondų investicijos Lietuvoje". Archived from the original on 27 April 2016.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Moody's (8 September 2017). "Rating Action: Moody's affirms Lithuania's A3 rating, outlook remains stable". moodys.com. Moody's. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Fitch Ratings Upgraded Lithuania's Credit Rating Outlook To "Positive"". 10 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Scope affirms Lithuania's credit rating at A- and revises the Outlook to Positive". 4 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Official reserve assets". lb.lt. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Level of GDP per capita and productivity". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Lithuania. GDP (current US$)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Lithuanias Year 2012 Budget Deficit Set Bellow 3 per cent GDP". bns.lt. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Statistics Lithuania". Stat.gov.lt. 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Lietuvos makroekonomikos apzvalga" (PDF). SEB Bankas. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Lithuania rules out devaluation". Retrieved 18 November 2018.

But Mr Kubilius, speaking in Brussels ahead of an EU summit, said his government would press ahead with its austerity programme and would not request a relaxation of the terms for joining the euro area that are set out under EU treaty law.

- "OECD Economic Surveys. LITHUANIA" (PDF). OECD. July 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

Lithuania’s fiscal position is sound. After revenues fell sharply in the wake of the 2008 crisis, the government started consolidating public finances on the spending side by reducing the wage bill, lowering social spending and cutting infrastructure investment. The 2016 budget resulted in a 0.3% surplus, the first for more than a decade (Figure 13). As a result, gross debt is now stabilising at around 50% of GDP (OECD National Accounts definition), which is sustainable under various simulations (Fournier and Bétin, forthcoming). The budget remained positive in 2017 and is expected so in 2018.

- "Rankings – Doing Business – The World Bank Group". Doing Business. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Lithuania information on economic freedom | Facts, data, analysis, charts and more". Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Tiesioginės užsienio investicijos Lietuvoje pagal šalį – Lietuvos bankas". 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018.

- Dencik, Jacob; Spee, Roel (July 2018). "Global Location Trends – 2018 Annual Report: Getting ready for Globalization 4.0" (PDF). IBM Institute for Business Value. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

Ireland continues to lead the world for attracting high-value investment, generating substantial inward investment with strengths in key high-value sectors such as ICT, financial and business services and life sciences. But Singapore is now a close second, with Lithuania and Switzerland right behind.

- "Population with tertiary education". data.oecd.org. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Lithuanian Institutions Enhance Focus on New Financial Technologies and Fintech Sector Development in Lithuania". finmin.lrv.lt. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- IBP, Inc. Lithuania Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Ed. Lulu.com 2015. Vol. 1. p. 175 Google Books. Lulu.com, 30 January 2015. Web. 3 March 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=-Tr_CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA175#v=onepage&q&f=false ISBN 0739779109, 9780739779101

- "Monument made of coins in central Vilnius to memorialise the litas and pay tribute to first Governor of Bank of Lithuania". lb.lt. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ""Trumpas lino žydėjimas, ilgas lino gyvenimas…"". sirvinta.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Valančius, Grigas. "The Economic Development and Foreign Trade of Lithuania". lituanus.org. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- "Lithuania – Official Gateway to Lithuania – History". Lietuva.lt. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Background Note: Lithuania". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Ziemele, Ineta (31 October 2003). Baltic Yearbook of International Law, 2003. p. 154. ISBN 978-90-04-13746-2. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Klimantas, Adomas; Zirgulis, Aras (16 July 2019). "A new estimate of Lithuanian GDP for 1937: How does interwar Lithuania compare?". Cliometrica. doi:10.1007/s11698-019-00189-8. ISSN 1863-2513.

- Eduardas Vilkas. "Privatisation in Lithuania" (PDF). euro.lt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2014.

- "Gross value added share by economic sector, year – Database of Indicators – data and statistics". Db1.stat.gov.lt. 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Foreign trade | Statistics Lithuania". Stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "General Report 1999 - Chapter V: Enlargement – Section 4: Accession negotiations (3/3)". Archived from the original on 31 December 2007.

- "Pradžia". Infolex.Lt. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Giovanna Maria Dora Dore (28 January 2015). "Hopping on a Sinking Ship?". The American Interest. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015.

- "NASDAQ OMX Baltic". NASDAQ OMX Baltic. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Turukapitalisatsioon". Aktsiad, Vabaturg, Vilniuse börs. 26 November 2009.

- Structure of gross value added by kind of economic activity and year Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Rodiklių duomenų bazė". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Lithuania. GDP (current US$)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Bank of Lithuania : Statistics". Lb.lt. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Davulis, Prof. Gediminas. "ANTI-CRISIS MEASURES OF ECONOMIC POLICY IN LITHUANIA AND IN OTHER BALTIC COUNTRIES" (PDF). eujournal.org. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

Guided by these hopes, both enterprises and households began borrowing for consumption and business ever more and all the more that the banks granted loans with engaging interests. The largest share of loans received by a household was aimed at the real estate market. This process was stimulated by state given tax privileges for lodgings loans which established conditions of forming a real estate bubble. According to the data of the Bank of Lithuania, the volume of loans to acquire lodgings has grown from 50 million Lt in 2004 up to 720 million Lt in 2007. Such an expansion of credit had a decisive influence to form a 'bubble' in the Lithuanian real estate market.

- "Statistics Lithuania". Stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- Åslund, Anders (28 November 2011). "Lithuania's remarkable recovery". euobserver.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

This year, Lithuania is one of the fastest growing economies in Europe with an annualized growth rate of 6.6 percent during the first half of the year. This high growth is driven by an exports surge of no less than 38 percent. This is an incredible achievement after a vicious financial crisis. Remember that Lithuania’s GDP slumped by 14.7 percent in 2009. The explanation is rigorous government policy. Lithuania’s attainment is often ignored or belittled because its neighbors Estonia and Latvia have carried out similar miracles, but they are all true heroes, and Lithuania’s cure looks remarkable also among this tough competition.

- "Lithuania.Current account balance (% of GDP)". data.worldbank.org. The World Bank. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Statistical yearbook of Lithuania. 2018". osp.stat.gov.lt. p. 324. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Lithuanian exports which grew most across Europe last year will beat value records this year". verslilietuva.lt. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "OECD Better Life. Lithuania". Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Are Lithuanian residents happy in their own country?". lb.lt. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "World Happiness Report" (PDF). pp. 20–21. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT FLOW DOUBLED IN 2017". The Bank of Lithuania and Statistics Lithuania. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Lithuania – one of the fastest-growing in EU Innovation area". Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Free Economic Zones With Tax Benefits And One-Stop-Shop Services". InvestLithuania.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Industrial Parks". InvestLithuania.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "WORLD INVESTMENT REPORT 2019: Special Economic Zones" (PDF). unctad.org. p. 152. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "Lithuania. BUREAU OF ECONOMIC AND BUSINESS AFFAIRS 2018. Investment Climate Statements". Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Dar 100 gamyklų per ateinančius penkerius metus". vz.lt. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Manufacturing Risk Index 2018" (PDF). Cushman & Wakefield.

- "EY Attractiveness Survey: Europe" (PDF). p. 11.

- "Coface Baltic Top 50 – 2019". Coface Central Europe. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Productivity - GDP per hour worked - OECD Data". 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018.

- "Darbo jėga ir darbo jėgos aktyvumo lygis pagal amžiaus grupes ir lytį". osp.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Average wages Total, US dollars, 1990 – 2017". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Unemployment rate". osp.stat.gov.lt. Statistics Lithuania. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Population with tertiary education". data.oecd.org. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Education at a glance 2017. Lithuania" (PDF). gpseducation.oecd.org. p. 2. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "OECD Economic Surveys LITHUANIA. 2016" (PDF). oecd.org. 24 March 2016. p. 22. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "2019 Shows Biggest Leap for Lithuania". Retrieved 26 December 2018.

The 2017 labor law reform significantly improved Lithuania’s position in the Employment Flexibility Index, moving the country from the 27th to 15th position among the EU and OECD countries, according to Employment Flexibility Index 2019 compiled by the Lithuanian Free Market Institute based on the World Bank’s Doing Business data.

- "Global Wealth Report 2019" (PDF). Credit Suisse. p. 21. Retrieved 15 December 2020. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Global Wealth Databook" (PDF). Credit Suisse. November 2017. p. 24. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Household debt". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "The rise of Lithuania as a force in IT: Why Google and Nasdaq are investing here". zdnet.com. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Bank of Lithuania". Lb.lt. 18 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Bank of Lithuania". Lb.lt. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Bank of Lithuania". Lb.lt. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "This Country Wants a Piece of London's Fintech". Bloomberg.com. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Lithuania Registered 35 New Fintech Companies in 2017". crowdfundinsider.com. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Kostaki, Irene. "Lithuania debuts as EU gateway for global blockchain industry". neweurope.eu. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

The Lithuanian capital Vilnius launched Europe’s first international Blockchain Centre on 27 January, making it the EU’s only hub for the digital ledger. The new hub will help Europe connect with partner Blockchain Centres in Australia, China, Canada, the UK, Belgium, Denmark, Georgia, Gibraltar, Ukraine, Israel, and Latvia.

- "Vilnius Aims To Attract Companies Scared of Brexit". forbes.com. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Brexit a boon for Lithuania's 'fintech' drive". businesstimes.com.sg. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Milda Šeputytė; Jeremy Kahn (21 December 2018). "Google Payment Expands With E-Money License From Lithuania". bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Google Payment, a company owned by Alphabet Inc., obtained an e-money license in Lithuania, joining a growing number of fintech firms that have secured permission from the Baltic nation to offer financial services across the European Union.

- "Fintech Locations of the Future 2019/20: London tops first ranking". fdiintelligence.com. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Regulatory sandbox". lb.lt. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "FinTech companies showed avid interest in the LBChain project". lb.lt. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Moody's to open Vilnius office". emerging-europe.com. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

"After long and careful deliberation, we chose Vilnius because of its educated and multilingual talent pool, its highly-developed IT infrastructure and its business-friendly environment", said Duncan Neilson, a Moody’s senior vice president. "Given our goals of hiring diverse talent and further developing our automation and cyber security capabilities, choosing Lithuania as our newest EU location makes good business sense".

- Rimantas Rudzkis; Natalja Titova. "Manufacturing Industry Trends in Lithuania". Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "Lithuanian furniture makers among Ikea's biggest suppliers". lrt.lt. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

Aivaras Čičelis, deputy president at SEB Bank and head of Corporate Banking Division, said that "there were fears before that Lithuanian furniture makers would be pushed out of business by the Chinese and Indians, but this sector benefited from the financial crisis, when everyone was looking for cheap furniture and turned to Ikea, which sells Lithuanian production.“

- "Continental Expands its Presence in Europe and Builds First Plant in Lithuania". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Hella officially opens its electronics plant in Lithuania". Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "lepa.lt – Domenai, domenų registravimas – UAB "Interneto vizija"" (PDF). lepa.lt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Bancroft, Dani. "What is Lithuania's role in European Biotech?". labiotech.eu. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

Nowadays, as a member of the NATO, the European Union, and Eurozone, Lithuania’s life science sector is growing around 20–25% annually; with special focus on the production and research of biotechnology, pharmaceutical and medical devices. Many of the products developed in Lithuania are geared towards international markets, with 90% of all life science products and services being exported around the world.

- "Lithuania, a leading light in laser technology". Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "Growing impact of tourism on the Lithuanian economy". tourism.lt. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "2017 TOURISM IN LITHUANIA". osp.stat.gov.lt. p. 7. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

In 2017, compared to 2016, the number foreign tourists grew by 4.4 per cent and totaled 1.6 million. The largest number of foreign tourists staying in the accommodation establishments of Lithuania came from Belarus (177 thousand), Germany (176.2 thousand), Russia (168.1 thousand), also from neighbouring countries – Poland (161.4 thousand), and Latvia (152.3 thousand). In 2017, the number of tourists increased from China (33.4 per cent), Greece (27.5 per cent), Luxembourg (24.3 per cent), Iceland (23.6 per cent), Canada (22.3 per cent), USA (21.6 per cent).

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on 4 January 2018.

- "Farm crops in the country by kind, type of farm – Database of Indicators – data and statistics". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Number of livestock and poultry by kind, period – Database of Indicators – data and statistics". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Consumption of main foodstuffs per capita by product – Database of Indicators – data and statistics". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Indicators database – Oficialiosios statistikos portalas". osp.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017.

- "BENDRASIS VIDAUS PRODUKTAS PAGAL APSKRITIS 2018 M." (in Lithuanian). Statistics Lithuania. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- "Statistics Lithuania". Stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Structure of gross value added by kind of economic activity (31), year – Database of Indicators – data and statistics". Db1.stat.gov.lt. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Communications" Archived 4 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Lithuania, World Factbook, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 13 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Uptime Institute. Country: Lithuania, Tier Level: Tier III". Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Colocation Lithuania – Data Centers". Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Lithuanian Communications Sector 2013" (PDF). Communications Regulatory Authority of the Republic of Lithuania. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "ICT Infrastructure". Invest Lithuania. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- "Nuclear energy – Visaginas Nuclear Power Plant Project". Vae.lt. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Lithuania becomes first ex-Soviet state to buy US natural gas". Financial Times (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Lithuania breaks Gazprom's monopoly by signing first LNG deal". Euractiv.com (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Klaipėda LNG terminal Factsheet" (PDF). Ministry of Energy of the Republic of Lithuania. 27 October 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Klaipėda LNG Terminal one year on – independence or responsibility?". Lrt.lt. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Lithuanian Energy plans to set up industrial park at Kruonis plant". 15min.lt. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Questions and answers on the synchronisation of the Baltic States' electricity networks with the continental European network (CEN)". 28 June 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Excellent Infrastructure". Lepa.lt. 21 December 2007. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Lietuvos geležinkeliai". Litrail.lt. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Lietuvos geležinkeliai". Litrail.lt. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Marvelės uostą pasiekė pirmasis krovinys!". klaipeda.diena.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Eksportas, importas pagal valstybes" (PDF). Statistics Lithuania. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Neegzistuoja - Serveriai.lt" (PDF). www.lda.lt.

- "In 2017, exports increased by 16.8%, imports – 15.5% in Lithuania". baltic-course.com. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 10 September 2018.

External links

- Lithuania's Department of Statistics

- Bank of Lithuania Statistics

- Non-profit organization Invest Lithuania

- Lithuania’s Economic Outlook for 2017–2020

- Main Lithuanian indicators

- Lithuania in figures 2017

![]()