Republic of Genoa

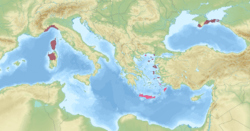

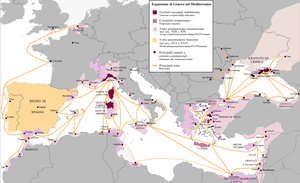

The Republic of Genoa (Italian: Repubblica di Genova; Ligurian: Repúbrica de Zêna [ɾeˈpybɾika de ˈzeːna]; Latin: Res Publica Ianuensis) was an independent state and maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast, incorporating Corsica from 1347 to 1768, and numerous other territories throughout the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Republic of Genoa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

Motto: Respublica superiorem non recognoscens (Latin for '"Republic that recognizes [lit. 'recognizing'] no superior"') | |||||||||||||

The Republic of Genoa in the early modern period | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Genoa | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ligurian Italian Latin Corsican Greek | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||

| Government | Oligarchic merchant republic | ||||||||||||

| Doge | |||||||||||||

• 1339–1345 | Simone Boccanegra (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1795–1797 | Giacomo Maria Brignole (last) | ||||||||||||

| Capitano del popolo | |||||||||||||

• 1257–1262 | Guglielmo Boccanegra (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1335–1339 | Galeotto Spinola (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||||||

• Established | 11th century | ||||||||||||

• Participation in the First Crusade | 1096–1099 | ||||||||||||

| 1261 | |||||||||||||

| 1284 | |||||||||||||

• Creation of the Dogate | 1339 | ||||||||||||

• Foundation of the Bank of Saint George | 1407 | ||||||||||||

• Andrea Doria's new constitution | 1528 | ||||||||||||

| June 14, 1797 | |||||||||||||

• Republic's revival | 1814 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1815 | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• Estimate | 600,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Lira Genovese | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Italy France Greece Tunisia Syria Turkey Ukraine Romania Russia Monaco | ||||||||||||

Known as "la Superba" ("the Superb one"), "la Dominante" ("The Dominant one"), "la Dominante dei mari" ("the Dominant of the Seas"), and "la Repubblica dei magnifici" ("the Republic of the Magnificents"), during the late Middle Ages Genoa was one of the main commercial powers of the Mediterranean Sea, while between the 16th and 17th centuries it was one of the major financial centers in Europe.

It was a celebrated maritime republic and today its coat of arms is depicted in the flag of the Italian Navy. In 1284, Genoa fought victoriously against the Republic of Pisa in the battle of Meloria for the dominance over the Tyrrhenian Sea, and it was an eternal rival of Venice for dominance in the Mediterranean Sea.

From 1339 until the state's extinction in 1797 the ruler of the republic was the Doge, originally elected for life, after 1528 was elected for terms of two years.

The republic began when Genoa became a self-governing commune in the 11th century and ended when it was conquered by the French First Republic under Napoleon and replaced with the Ligurian Republic. The Ligurian Republic was annexed by the First French Empire in 1805; its restoration was briefly proclaimed in 1814 following the defeat of Napoleon, but it was ultimately annexed by the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1815.

Name

.jpg)

It was officially known as Repubblica di Genova (Latin: Res Publica Ianuensis, Ligurian: Repúbrica de Zêna) and was nicknamed by Petrarch as La Superba, in reference to its glory and impressive landmarks. For over eight centuries the republic was also known as la Dominante (English: The Dominant one), la Dominante dei mari (English: the Dominant of the Seas), and la Repubblica dei magnifici (English: the Republic of the Magnificents).[1]

History

Backgound

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Ostrogoths occupied the city of Genoa. After the Gothic War, the Byzantines made it the seat of their vicar. When the Lombards invaded Italy in 568, Bishop Honoratus of Milan fled and held his seat in Genoa. The Lombards, under King Rothari, finally captured Genoa and other Ligurian cities in about 643. In 773 the Lombard Kingdom was annexed by the Frankish Empire; the first Carolingian count of Genoa was Ademarus, who was given the title praefectus civitatis Genuensis.[2]

In the year 958, a diploma granted by Berengar II of Italy gave full legal freedom to the city of Genoa, guaranteeing the possession of its lands in the form of landed lordships.[3] With this provision the process that will lead, at the end of the 11th century, to the constitution of the free municipality was started. A meeting of all the city's trade associations (compagnie), also comprising the noble lords of the surrounding valleys and coasts, finally signaled the birth of Genoese government. The then-born city-state was known as Compagna Communis. The local organization maintained a political and social significance for centuries, so much so that even in 1382 the members of the Grand Council were classified according to the companion they belonged to as well as according to the political faction divided between "noble" and "popular".[4]

Rise

Before 1100, Genoa emerged as an independent city-state, one of a number of Italian city-states during this period, nominally, the Holy Roman Emperor was overlord and the Bishop of Genoa was president of the city; however, actual power was wielded by a number of "consuls" annually elected by popular assembly. At that time Muslim raiders were attacking coastal cities on the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Muslims raided Pisa in 1004 and in 1015 they escalated their attacks, raiding Luni, with Mujahid al-Siqlabi, Emir of the Taifa of Denia attacking Sardinia with a fleet of 125 ships.[5] In 1016 the allied troops of Genoa and Pisa defended Sardinia. In 1066 war erupted between Genoa and Pisa – possibly over the control of Sardinia.[6]

The republic was one of the so-called "Maritime Republics" (Repubbliche Marinare), along with Venice, Pisa, Amalfi, Gaeta, Ancona and Ragusa.[7]

In 1087, Genoese and Pisan fleets led by Hugh of Pisa and accompanied by troops from Pantaleone of Amalfi, Salerno and Gaeta, attacked the North African city of Mahdia, the capital of the Fatimid Caliphate. The attack, supported by Pope Victor III, became known as the Mahdia campaign. The attackers captured the city, but couldn't hold it against Arab forces. After the burning of the Arab fleet in the city's harbor, the Genoese and Pisan troops retreated. The destruction of the Arab fleet gave control of the Western Mediterranean to Genoa, Venice, and Pisa. This enabled Western Europe to supply the troops of the First Crusade of 1096–1099 by sea.[8]

In 1092, Genoa and Pisa, in collaboration with Alfonso VI of León and Castile attacked the Muslim Taifa of Valencia. They also unsuccessfully besieged Tortosa with support from troops of Sancho Ramírez, King of Aragon.[9] In its early centuries Genoa was an important trading city and its power began to increase.

Genoa started expanding during the First Crusade. In 1097 Hugh of Châteauneuf, Bishop of Grenoble and William, Bishop of Orange, went to Genoa and preached in the church of San Siro in order to gather troops for the First Crusade. At the time the city had a population of about 10,000. Twelve galleys, one ship and 1,200 soldiers from Genoa joined the crusade. The Genoese troops, led by noblemen de Insula and Avvocato, set sail in July 1097.[10] The Genoese fleet transported and provided naval support to the crusaders, mainly during the siege of Antioch in 1098, when the Genoese fleet blockaded the city while the troops provided support during the siege.[10] In the siege of Jerusalem in 1099 Genoese crossbowmen led by Guglielmo Embriaco acted as support units against the defenders of the city.

After the capture of Antioch on May 3, 1098, Genoa forged an alliance with Bohemond of Taranto, who became the ruler of the Principality of Antioch. As a result, he granted them a headquarters, the church of San Giovanni, and 30 houses in Antioch. On May 6, 1098 a part of the Genoese army returned to Genoa with the relics of Saint John the Baptist, granted to the Republic of Genoa as part of their reward for providing military support to the First Crusade.[10] Many settlements in the Middle East were given to Genoa as well as favorable commercial treaties.[10]

Genoa later forged an alliance with King Baldwin I of Jerusalem (reigned 1100–1118). In order to secure the alliance Baldwin gave Genoa one-third of the Lordship of Arsuf, one-third of Caesarea, and one-third of Acre and its port's income.[10] Additionally the Republic of Genoa would receive 300 bezants every year, and one-third of Baldwin's conquest every time 50 or more Genoese soldiers joined his troops.[10]

The Republic's role as a maritime power in the region secured many favorable commercial treaties for Genoese merchants. They came to control a large portion of the trade of the Byzantine Empire, Tripoli (Libya), the Principality of Antioch, Cilician Armenia, and Egypt.[10] Although Genoa maintained free-trading rights in Egypt and Syria, it lost some of its territorial possessions after Saladin's campaigns in those areas in the late 12th century.[11][12]

In 1147, Genoa took part in the Siege of Almería, helping Alfonso VII of León and Castile reconquer that city from the Muslims. After the conquest the republic leased out its third of the city to one of its own citizens, Otto de Bonvillano, who swore fealty to the republic and promised to guard the city with three hundred men at all times.[13] This demonstrates how Genoa's early efforts at expanding her influence involved enfeoffing private citizens to the commune and controlling overseas territories indirectly, rather than through the republican administration. In 1148, it joined the Siege of Tortosa and helped Count Raymond Berengar IV of Barcelona take that city, for which it also received a third.

Over the course of the 11th and particularly the 12th centuries, Genoa became the dominant naval force in the Western Mediterranean, as its erstwhile rivals Pisa and Amalfi declined in importance. Genoa (along with Venice) succeeded in gaining a central position in the Mediterranean slave trade at this time. This left the Republic with only one major rival in the Mediterranean: Venice.

Genoese Crusaders brought home a green glass goblet from the Levant, which Genoese long regarded as the Holy Grail. Not all of Genoa's merchandise was so innocuous, however, as medieval Genoa became a major player in the slave trade.[14]

Thirteenth and fourteenth century

The commercial and cultural rivalry of Genoa and Venice was played out through the thirteenth century. The Republic of Venice played a significant role in the Fourth Crusade, diverting "Latin" energies to the ruin of its former patron and present trading rival, Constantinople. As a result, Venetian support of the newly established Latin Empire meant that Venetian trading rights were enforced, and Venice gained control of large portion of the commerce of the eastern Mediterranean.[11]

In order to regain control of the commerce, the Republic of Genoa allied with Michael VIII Palaiologos Emperor of Nicaea, who wanted to restore the Byzantine Empire by recapturing Constantinople. In March 1261 the treaty of the alliance was signed in Nymphaeum.[11] On July 25, 1261, Nicaean troops under Alexios Strategopoulos recaptured Constantinople.[11]

As a result, the balance of favour tipped toward Genoa, which was granted free trade rights in the Nicene Empire. Besides the control of commerce in the hands of Genoese merchants, Genoa received ports and way stations in many islands and settlements in the Aegean Sea.[11] The islands of Chios and Lesbos became commercial stations of Genoa as well as the city of Smyrna (Izmir).

Genoa and Pisa became the only states with trading rights in the Black Sea.[11] In the same century the Republic conquered many settlements in Crimea, where the Genoese colony of Caffa was established. The alliance with the restored Byzantine Empire increased the wealth and power of Genoa, and simultaneously decreased Venetian and Pisan commerce. The Byzantine Empire had granted the majority of free trading rights to Genoa. In 1282 Pisa tried to gain control of the commerce and administration of Corsica, after being called for support by the judge Sinucello who revolted against Genoa. In August 1282, part of the Genoese fleet blockaded Pisan commerce near the river Arno. During 1283 both Genoa and Pisa made war preparations. Genoa built 120 galleys, 60 of which belonged to the Republic, while the other 60 galleys were rented to individuals. More than 15,000 mercenaries were hired as rowmen and soldiers. The Pisan fleet avoided combat, and tried to wear out the Genoese fleet during 1283. On August 5, 1284, in the naval Battle of Meloria the Genoese fleet, consisting of 93 ships led by Oberto Doria and Benedetto I Zaccaria, defeated the Pisan fleet, which consisted of 72 ships and was led by Alberto Morosini and Ugolino della Gherardesca. Genoa captured 30 Pisan ships, and sank seven. About 8,000 Pisans were killed during the battle, more than half of the Pisan troops, which were about 14,000. The defeat of Pisa, which never fully recovered as a maritime competitor, resulted in gain of control of the commerce of Corsica by Genoa. The Sardinian town of Sassari, which was under Pisan control, became a commune or self-styled "free municipality" which was controlled by Genoa. Control of Sardinia, however, did not pass permanently to Genoa: the Aragonese kings of Naples disputed control and did not secure it until the fifteenth century.

Genoese merchants pressed south, to the island of Sicily, and into Muslim North Africas, where Genoese established trading posts, pursuing the gold that traveled up through the Sahara and establishing Atlantic depots as far afield as Salé and Safi.[16] In 1283 the population of the Kingdom of Sicily revolted against the Angevin rule. The revolt became known as the Sicilian Vespers. As a result, the Aragonese rule was established on the Kingdom. Genoa, which had supported the Aragonese, was granted free trading and export rights in the Kingdom of Sicily. Genoese bankers also profited from loans to the new nobility of Sicily. Corsica was formally annexed in 1347.[17]

Genoa was far more than a depot of drugs and spices from the East: an essential engine of its economy was the weaving of silk textiles, from imported thread, following the symmetrical styles of Byzantine and Sassanian silks.

As a result of the economic retrenchment in Europe in the late fourteenth century, as well as its long war with Venice, which culminated in its defeat at Chioggia (1380), Genoa went into decline. This pivotal war with Venice has come to be called the War of Chioggia because of this decisive battle which resulted in the defeat of Genoa at the hands of Venice.[18] Prior to the War of Chioggia, which lasted from 1379 until 1381, the Genoese had enjoyed a naval ascendency that was the source of their power and position within northern Italy.[19] The Genoan defeat deprived Genoa of this naval supremacy, pushed it out of eastern Mediterranean markets and began the decline of the city-state.[19] Rising Ottoman power also cut into the Genoese emporia in the Aegean, and the Black Sea trade was reduced.[20]

In 1396, in order to protect the republic from internal unrest and the provocations of the Duke of Orléans and the former Duke of Milan, the Doge of Genoa Antoniotto Adorno made Charles VI of France the difensor del comune ("defender of the municipality") of Genoa. Though the republic had previously been under partial foreign control, this marked the first time Genoa was dominated by a foreign power.[21]

Golden age of Genovese bankers

-en.svg.png)

Though not well-studied, Genoa in the 15th century seems to have been tumultuous. The city had a strong tradition of trading goods from the Levant and its financial expertise was recognised all over Europe. After a brief period of French domination from 1394 to 1409, Genoa came under the rule of the Visconti of Milan. Genoa lost Sardinia to Aragon, Corsica to internal revolt, and its Middle Eastern, Eastern European, and Asia Minor colonies to the Ottoman Empire.[21]

In the 15th century two of the earliest banks in the world were founded in Genoa: the Bank of Saint George, founded in 1407, which was the oldest state deposit bank in the world at its closure in 1805 and the Banca Carige, founded in 1483 as a mount of piety, which still exists.

Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa c. 1451, and donated one-tenth of his income from the discovery of the Americas for Spain to the Bank of Saint George in Genoa for the relief of taxation on foods.

Threatened by Alfonso V of Aragon, the Doge of Genoa in 1458 handed the Republic over to the French, making it the Duchy of Genoa under the control of John of Anjou, a French royal governor. However, with support from Milan, Genoa revolted and the Republic was restored in 1461. The Milanese then changed sides, conquering Genoa in 1464 and holding it as a fief of the French crown.[22][23][24] Between 1463–1478 and 1488–1499, Genoa was held by the Milanese House of Sforza.[21] From 1499 to 1528, the Republic reached its nadir, being under nearly continual French occupation. The Spanish, with their intramural allies, the "old nobility" entrenched in the mountain fastnesses behind Genoa, captured the city on May 30, 1522, and subjected the city to a merciless pillage. When the great admiral Andrea Doria of the powerful Doria family allied with the Emperor Charles V to oust the French and restore Genoa's independence, a renewed prospect opened: 1528 marks the first loan from Genovese banks to Charles.[25]

Under the ensuing economic recovery, many aristocratic Genoese families, such as the Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini, and Serra, amassed tremendous fortunes. According to Felipe Fernandez-Armesto and others, the practices Genoa developed in the Mediterranean (such as chattel slavery) were crucial in the exploration and exploitation of the New World.[26]

At the time of Genoa's peak in the 16th century, the city attracted many artists, including Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Dyck. The architect Galeazzo Alessi (1512–1572) designed many of the city's splendid palazzi, as did in the decades that followed by fifty years Bartolomeo Bianco (1590–1657), designer of centrepieces of University of Genoa. A number of Genoese Baroque and Rococo artists settled elsewhere and a number of local artists became prominent.

Thereafter, Genoa underwent something of a revival as a junior associate of the Spanish Empire, with Genovese bankers, in particular, financing many of the Spanish crown's foreign endeavors from their counting houses in Seville. Fernand Braudel has even called the period 1557 to 1627 the "age of the Genovese", "of a rule that was so discreet and sophisticated that historians for a long time failed to notice it" (Braudel 1984 p. 157), although the modern visitor passing brilliant Mannerist and Baroque palazzo facades along Genoa's Strada Nova (now Via Garibaldi) or via Balbi cannot fail to notice that there was conspicuous wealth, which in fact was not Genovese but concentrated in the hands of a tightly-knit circle of banker-financiers, true "venture capitalists". Genoa's trade, however, remained closely dependent on control of Mediterranean sealanes, and the loss of Chios to the Ottoman Empire (1566), struck a severe blow.[27]

The opening for the Genovese banking consortium was the state bankruptcy of Philip II in 1557, which threw the German banking houses into chaos and ended the reign of the Fuggers as Spanish financiers. The Genovese bankers provided the unwieldy Habsburg system with fluid credit and a dependably regular income. In return the less dependable shipments of American silver were rapidly transferred from Seville to Genoa, to provide capital for further ventures. The Genovese banker Ambrogio Spinola, marqués de los Balbases, for instance, himself raised and led an army that fought in the Eighty Years' War in the Netherlands in the early 17th century. The decline of Spain in the 17th century brought also the renewed decline of Genoa, and the Spanish crown's frequent bankruptcies, in particular, ruined many of Genoa's merchant houses. In 1684 the city was heavily bombarded by a French fleet as punishment for its alliance with Spain.

Decline

In May 1625 a French-Savoian army briefly laid siege to Genoa. Though it was eventually lifted with the aid of the Spanish, the French would later bombard the city in May 1684 for its support of Spain during the War of the Reunions.[28] In-between, a plague killed as many as half of the inhabitants of Genoa in 1656–57.[29] Genoa continued its slow decline well into the 18th century, losing its last Mediterranean colony, the island fortress of Tabarka, to the Bey of Tunis in 1742.[30]

The Convention of Turin of 1742, in which Austria allied with the Kingdom of Sardinia, caused some consternation in the Republic. However, when this provisional relationship was given a more durable and reliable character in the signing of the Treaty of Worms, in 1743, the fear of diplomatic isolation had caused the Genoese Republic to abandon its neutrality and to ally with the House of Bourbon in the War of the Austrian Succession. Consequently, the Republic of Genoa signed a secret treaty with the Bourbon allies of Kingdom of France, Spanish Empire and Kingdom of Naples. On 26 June 1745, the Republic of Genoa declared war on the Kingdom of Sardinia.[31] This decision would prove disastrous for Genoa, which later surrendered to the Austrians in September 1746 and was briefly occupied before a revolt liberated the city two months later. The Austrians returned in 1747 and, along with a contingent of Sardinian forces, laid siege to Genoa before being driven off by the approach of a Franco-Spanish army.

Though Genoa retained its lands in the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, it was unable to keep its hold on Corsica in its weakened state. After driving out the Genoese, the Corsican Republic was declared in 1755. Eventually relying on French intervention to quash the rebellion, Genoa was forced to cede Corsica to the French in the 1768 Treaty of Versailles.

The end of the Republic and its brief revival of 1814

Already in 1794 and 1795 the revolutionary echoes from France reached Genoa, thanks to Genoese propagandists and refugees sheltered in the nearby state of the Alps, and in 1794 a conspiracy against the aristocratic and oligarchic ruling class that, in fact, was already waiting for it in the Genoese palaces of power. However, it was in May 1797 that the intent of the Genoese jacobins and French citizens to overthrow the government of the Doge Giacomo Maria Brignole took shape, giving rise to a fratricidal war in the streets between opponents and popular supporters of the current customs system.[32]

The direct intervention of Napoleon (during the Campaigns of 1796) and his representatives in Genoa was the final act that led to the fall of the Republic in early June, who overthrew the old elites which had ruled the state for all of its history, giving birth to the Ligurian Republic in June 14, 1797, under the watchful care of Napoleonic France. After Bonaparte's seizure of power in France, a more conservative constitution was enacted, but the Ligurian Republic's life was short—in 1805 it was annexed by France, becoming the départements of Apennins, Gênes, and Montenotte.[32]

With the fall of Napoleon, and the subsequent Congress of Vienna, Genoa regained an ephemeral independence, with the name of the Repubblica genovese, which lasted less than a year. However, the congress established the annexation of the territories, and therefore of the whole of Liguria with the Oltregiogo area and the island of Capraia to the Kingdom of Sardinia, governed by the House of Savoy, contravening the principle of restoring the legitimate governments and monarchies of the old Republic.[7]

Government

The history of Genoa, of the Genoese and of the republic that held its fate for a long time, but also of the governments that gradually took turns leading the city, to reach the time of the Doges, is traceable through the work of historians who have continued the storytelling work begun at the end of the 11th century by Caffaro Di Caschifellone (historian and himself municipal consul) with the "Annales ianuenses".[33]

The Republic of Genoa's governance history is divided into five stages:

- Consul: 11th century–1191

- Podestà: 1191–1256

- Capitano del popolo: 1257–1339

- Doge (elected for life): 1339–1528

- Doge (elected for terms of two years): 1528–1797

The republic was substantially democratic in shape, while those of the Podestàs and the Captains of the people strongly restored the often conflicting relationship between the authority and the freedom. The perpetual doges, on the other hand, proclaimed themselves popular, even though sometimes crossing the oligarchy; finally the fifth republic was institutionally aristocratic. By custom, prelates in Genoa were unable to take on public office.[34]

Aristocratic families

In the first two centuries from the institution of the dogato for life in Genoa, it was above all the Adorno (seven doges elected) and Fregoso (ten doges elected) families who fought the position.[35]

After the reform of 1528, among the seventy-nine "biennial Doges" who came to power, many were elected from a small number of noble houses in the city organized into 28 "Alberghi", in particular:

- Grimaldi: eleven doges.

- Spinola: eleven doges.

- Durazzo: eight doges.

- De Franchi, Giustiniani and Lomellini families: seven doges each.

- Centurione: six doges.

- Doria: six doges.

- Cattaneo and Gentile families: five doges each.

- Brignole: four doges.

- Imperiali: four doges.

- De Mari, Invrea and Negrone families: four doges each.

- Pallavicini: three doges.

- Sauli: three doges.

- Balbi, Cambiaso, Chiavari, Lercari, Pinelli, Promontorio, Veneroso, Viale and Zoagli families: two doges each.

- Della Torre: two doges.

- Assereto, Ayroli, Canevaro, Chiavica Cibo, Clavarezza, Da Passano, De Ferrari, De Fornari, De Marini, Di Negro, Ferreti, Franzoni, Frugoni, Garbarino, Giudice Calvi, Odone, Saluzzo, Senarega, Vacca and Vivaldi: one doge each

- Della Rovere: one doge.

Other influential families of the Republic of Genoa were:

- Fieschi: counts of Lavagna, and produced two Popes: Pope Innocent IV and Pope Adrian V

- Gattilusi: lords of numerous lands in the Aegean Sea, such as Lemnos, Lesbos, Enez and Samothrace.[35]

Territories during the Middle Ages

At the time of its founding in the early 11th century the Republic of Genoa consisted of the city of Genoa and the surrounding areas. As the commerce of the city increased, so did the territory of the Republic. By 1015 all of Liguria fell under the Republic of Genoa. After the First Crusade in 1098 Genoa gained settlements in Syria. (It lost the majority of them during the campaigns of Saladin in the 12th century.) In 1261 the city of Smyrna in Asia Minor became Genoese territory.[11]

In 1255 Genoa established the colony of Caffa in Crimea.[36] In the following years the Genoese established further colonies in Crimea: Soldaia, Cherco and Cembalo.[36] In 1275 the Byzantine Empire granted the islands of Chios and Samos to Genoa.[36]

Between 1316 and 1332 Genoa established the Black Sea colonies of La Tana (present-day Azov) and Samsun in Anatolia. In 1355 the Byzantine Emperor John V Palaiologos granted Lesbos to a Genoese lord. At the end of the 14th century the colony of Samastri was established in the Black Sea and Cyprus was granted to the Republic. At that period the Republic of Genoa also controlled one quarter of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire, and Trebizond, capital of the Empire of Trebizond.[36] The Ottoman Empire conquered most of the Genoese overseas territories during the 15th century.[36]

Other territories outside mainland Italy

- Giudicato of Logudoro (island of Sardinia) 1259–1325

- North Aegean sea possessions, centered at Chios 1261–1566

- Southern Crimea possessions of Gazaria 1266–1475 (lost to Ottoman Empire, Kefe Eyalet)

- Island of Corsica 1284–1768

- City of Tabarka north west of Tunisia 1540–1742

- The cities of Calafat, Giurgiu and Galați, about the 14th century (present day Romania)

- Port of Panama (1520–1671) From about 1520 the Genoese controlled the port of Panama, the first port on the Pacific founded by the conquest of the Americas; the Genoese obtained a concession to exploit the port mainly for the slave trade of the new world on the Pacific, until the destruction of the primeval city in 1671.[37][38]

See also

References

Notes

- The Roman Catholicism was the State and predominant religion of the Republic, but the following religions were also present both in the city of Genoa and in its colonies: Eastern Orthodox, Judaism and Islam.

Citations

- "Genova "la Superba": l'origine del soprannome". GenovaToday (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- the Deacon, Paul. Historia Langobardorum. IV.45.

- "RM Strumenti - La città medievale italiana - Testimonianze, 13". www.rm.unina.it. Retrieved 2020-08-15.

- Mallone Di Novi, Cesare Cattaneo (1987). I "Politici" del Medioevo genovese: il Liber Civilitatis del 1528 (in Italian). pp. 184–193.

- Kirk, Thomas Allison (2005). Genoa and the Sea: Policy and Power in an Early Modern Maritime Republic. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-8018-8083-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kirk 2005, p. 188.

- G. Benvenuti - Le Repubbliche Marinare. Amalfi, Pisa, Genova, Venezia - Newton & Compton editori, Roma 1989; Armando Lodolini, Le repubbliche del mare, Biblioteca di storia patria, 1967, Roma.

- J. F. Fuller (1987). A Military History of the Western World, Volume I. Da Capo Press. p. 408. ISBN 0-306-80304-6.

- Joseph F. O'Callaghan (2004). Reconquest and crusade in medieval Spain. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8122-1889-2.

- Steven A. Epstein (2002). Genoa and the Genoese, 958–1528. UNC Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 0-8078-4992-8.

- Alexander A. Vasiliev (1958). History of the Byzantine Empire, 324–1453. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 537–38. ISBN 0-299-80926-9.

- Robert H. Bates (1998). Analytic Narratives. Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-691-00129-4.

- John Bryan Williams, "The Making of a Crusade: The Genoese Anti-Muslim Attacks in Spain, 1146–1148" Journal of Medieval History 23 1 (1997): 29–53.

- Steven A. Epstein, Speaking of Slavery: Color, Ethnicity, and Human Bondage in Italy (Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past.

- H. Hearder and D.P. Waley, eds, A Short History of Italy (Cambridge University Press)1963:68.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 1910, Volume 7, page 201.

- John Julius Norwich, History of Venice (Alfred A. Knopf Co.: New York, 1982) p. 256.

- Lucas, Henry S. (1960). The Renaissance and the Reformation. New York: Harper & Bros. p. 42.

- Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1953). The Story of Civilization. 5 - The Renaissance. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 189.

- Kirk, Thomas Allison (2005). Genoa and the Sea: Policy and Power in an Early Modern Maritime Republic. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8018-8083-1.

- Vincent Ilardi, The Italian League and Francesco Sforza – A Study in Diplomacy, 1450–1466 (Doctoral dissertation – unpublished: Harvard University, 1957) pp. 151–3, 161–2, 495–8, 500–5, 510–12.

- Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II), The Commentaries of Pius II, eds. Florence Alden Gragg, trans., and Leona C. Gabel (13 books; Smith College: Northampton, Massachusetts, 1936-7, 1939–40, 1947, 1951, 1957) pp. 369–70.

- Vincent Ilardi and Paul M. Kendall, eds., Dispatches of Milanese Ambassadors, 1450–1483(3 vols; Ohio University Press: Athens, Ohio, 1970, 1971, 1981) vol. III, p. xxxvii.

- "Andrea Doria | Genovese statesman". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- Before Columbus: Exploration and Colonization from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, 1229-1492.

- Philip P. Argenti, Chius Vincta or the Occupation of Chios by the Turks (1566) and Their Administration of the Island (1566–1912), Described in Contemporary Diplomatic Reports and Official Dispatches (Cambridge, 1941), Part I.

- Genoa 1684, World History at KMLA.

- Early modern Italy (16th to 18th centuries) » The 17th-century crisis Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Alberti Russell, Janice. The Italian community in Tunisia, 1861–1961: a viable minority. pag. 142.

- S. Browning, Reed. WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION. Griffin. p. 205.

- Benvenuti, Gino. Storia della Repubblica di Genova (in Italian). Ugo Mursia Editore. pp. 40–120.

- Donaver, Federico. Storia di Genova (in Italian). Nuova Editrice Genovese. p. 15.

- Donaver, Federico. LA STORIA DELLA REPUBBLICA DI GENOVA (in Italian). Libreria Editrice Moderna. p. 77.

- Battilana, Natale. Genealogie delle famiglie nobili di Genova (in Italian). Forni.

- William Miller (2009). The Latin Orient. Bibliobazaar LLC. pp. 51–54. ISBN 1-110-86390-X.

- "I Genovesi d'Oltremare i primi coloni moderni". www.giustiniani.info. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- "15. Casa de los Genoveses - Patronato Panamá Viejo". www.patronatopanamaviejo.org. Retrieved 2020-08-05.