Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino[2] (Italian: [raffaˈɛllo ˈsantsjo da urˈbiːno]; March 28 or April 6, 1483 – April 6, 1520),[3][lower-alpha 1] known as Raphael (/ˈræfeɪəl/, US: /ˈræfiəl, ˈreɪf-, ˌrɑːfaɪˈɛl, ˌrɑːfiˈɛl/), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur.[5] Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, he forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period.[6]

Raphael | |

|---|---|

Presumed portrait of Raphael[1] | |

| Born | Raffaello Santi (or Sanzio) March 28 or April 6, 1483 |

| Died | April 6, 1520 (aged 37) |

| Resting place | The Pantheon, Rome |

| Known for | |

Notable work | list |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

Raphael was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop and, despite his early death at 37, leaving a large body of work. Many of his works are found in the Vatican Palace, where the frescoed Raphael Rooms were the central, and the largest, work of his career. The best known work is The School of Athens in the Vatican Stanza della Segnatura. After his early years in Rome, much of his work was executed by his workshop from his drawings, with considerable loss of quality. He was extremely influential in his lifetime, though outside Rome his work was mostly known from his collaborative printmaking.

After his death, the influence of his great rival Michelangelo was more widespread until the 18th and 19th centuries, when Raphael's more serene and harmonious qualities were again regarded as the highest models. His career falls naturally into three phases and three styles, first described by Giorgio Vasari: his early years in Umbria, then a period of about four years (1504–1508) absorbing the artistic traditions of Florence, followed by his last hectic and triumphant twelve years in Rome, working for two Popes and their close associates.[7]

Background

Raphael was born in the small but artistically significant central Italian city of Urbino in the Marche region,[8] where his father Giovanni Santi was court painter to the Duke. The reputation of the court had been established by Federico da Montefeltro, a highly successful condottiere who had been created Duke of Urbino by Pope Sixtus IV – Urbino formed part of the Papal States – and who died the year before Raphael was born. The emphasis of Federico's court was more literary than artistic, but Giovanni Santi was a poet of sorts as well as a painter, and had written a rhymed chronicle of the life of Federico, and both wrote the texts and produced the decor for masque-like court entertainments. His poem to Federico shows him as keen to demonstrate awareness of the most advanced North Italian painters, and Early Netherlandish artists as well. In the very small court of Urbino he was probably more integrated into the central circle of the ruling family than most court painters.[9]

Federico was succeeded by his son Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, who married Elisabetta Gonzaga, daughter of the ruler of Mantua, the most brilliant of the smaller Italian courts for both music and the visual arts. Under them, the court continued as a centre for literary culture. Growing up in the circle of this small court gave Raphael the excellent manners and social skills stressed by Vasari.[10] Court life in Urbino at just after this period was to become set as the model of the virtues of the Italian humanist court through Baldassare Castiglione's depiction of it in his classic work The Book of the Courtier, published in 1528. Castiglione moved to Urbino in 1504, when Raphael was no longer based there but frequently visited, and they became good friends. Raphael became close to other regular visitors to the court: Pietro Bibbiena and Pietro Bembo, both later cardinals, were already becoming well known as writers, and would later be in Rome during Raphael's period there. Raphael mixed easily in the highest circles throughout his life, one of the factors that tended to give a misleading impression of effortlessness to his career. He did not receive a full humanistic education however; it is unclear how easily he read Latin.[11]

Early life and work

Raphael's mother Màgia died in 1491 when he was eight, followed on August 1, 1494 by his father, who had already remarried. Raphael was thus orphaned at eleven; his formal guardian became his only paternal uncle Bartolomeo, a priest, who subsequently engaged in litigation with his stepmother. He probably continued to live with his stepmother when not staying as an apprentice with a master. He had already shown talent, according to Vasari, who says that Raphael had been "a great help to his father".[12] A self-portrait drawing from his teenage years shows his precocity.[13] His father's workshop continued and, probably together with his stepmother, Raphael evidently played a part in managing it from a very early age. In Urbino, he came into contact with the works of Paolo Uccello, previously the court painter (d. 1475), and Luca Signorelli, who until 1498 was based in nearby Città di Castello.[14]

According to Vasari, his father placed him in the workshop of the Umbrian master Pietro Perugino as an apprentice "despite the tears of his mother".[lower-alpha 2] The evidence of an apprenticeship comes only from Vasari and another source,[16] and has been disputed; eight was very early for an apprenticeship to begin. An alternative theory is that he received at least some training from Timoteo Viti, who acted as court painter in Urbino from 1495.[17] Most modern historians agree that Raphael at least worked as an assistant to Perugino from around 1500; the influence of Perugino on Raphael's early work is very clear: "probably no other pupil of genius has ever absorbed so much of his master's teaching as Raphael did", according to Wölfflin.[18] Vasari wrote that it was impossible to distinguish between their hands at this period, but many modern art historians claim to do better and detect his hand in specific areas of works by Perugino or his workshop. Apart from stylistic closeness, their techniques are very similar as well, for example having paint applied thickly, using an oil varnish medium, in shadows and darker garments, but very thinly on flesh areas. An excess of resin in the varnish often causes cracking of areas of paint in the works of both masters.[19] The Perugino workshop was active in both Perugia and Florence, perhaps maintaining two permanent branches.[20] Raphael is described as a "master", that is to say fully trained, in December 1500.[21]

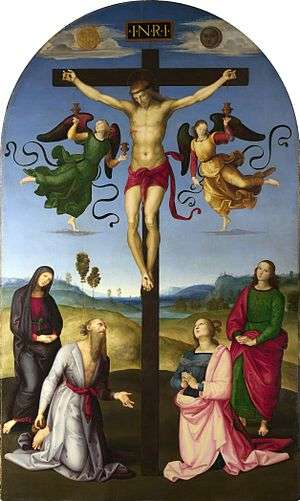

His first documented work was the Baronci altarpiece for the church of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino in Città di Castello, a town halfway between Perugia and Urbino.[22] Evangelista da Pian di Meleto, who had worked for his father, was also named in the commission. It was commissioned in 1500 and finished in 1501; now only some cut sections and a preparatory drawing remain.[23] In the following years he painted works for other churches there, including the Mond Crucifixion (about 1503) and the Brera Wedding of the Virgin (1504), and for Perugia, such as the Oddi Altarpiece. He very probably also visited Florence in this period. These are large works, some in fresco, where Raphael confidently marshals his compositions in the somewhat static style of Perugino. He also painted many small and exquisite cabinet paintings in these years, probably mostly for the connoisseurs in the Urbino court, like the Three Graces and St. Michael, and he began to paint Madonnas and portraits.[24] In 1502 he went to Siena at the invitation of another pupil of Perugino, Pinturicchio, "being a friend of Raphael and knowing him to be a draughtsman of the highest quality" to help with the cartoons, and very likely the designs, for a fresco series in the Piccolomini Library in Siena Cathedral.[25] He was evidently already much in demand even at this early stage in his career.[26]

The Coronation of the Virgin 1502–3 (Pinacoteca Vaticana)

The Coronation of the Virgin 1502–3 (Pinacoteca Vaticana) The Wedding of the Virgin, Raphael's most sophisticated altarpiece of this period (Pinacoteca di Brera)

The Wedding of the Virgin, Raphael's most sophisticated altarpiece of this period (Pinacoteca di Brera) Saint George and the Dragon, a small work (29 x 21 cm) for the court of Urbino (Louvre)

Saint George and the Dragon, a small work (29 x 21 cm) for the court of Urbino (Louvre)

Influence of Florence

Raphael led a "nomadic" life, working in various centres in Northern Italy, but spent a good deal of time in Florence, perhaps from about 1504. Although there is traditional reference to a "Florentine period" of about 1504–8, he was possibly never a continuous resident there.[27] He may have needed to visit the city to secure materials in any case. There is a letter of recommendation of Raphael, dated October 1504, from the mother of the next Duke of Urbino to the Gonfaloniere of Florence: "The bearer of this will be found to be Raphael, painter of Urbino, who, being greatly gifted in his profession has determined to spend some time in Florence to study. And because his father was most worthy and I was very attached to him, and the son is a sensible and well-mannered young man, on both accounts, I bear him great love..."[28]

As earlier with Perugino and others, Raphael was able to assimilate the influence of Florentine art, whilst keeping his own developing style. Frescos in Perugia of about 1505 show a new monumental quality in the figures which may represent the influence of Fra Bartolomeo, who Vasari says was a friend of Raphael. But the most striking influence in the work of these years is Leonardo da Vinci, who returned to the city from 1500 to 1506. Raphael's figures begin to take more dynamic and complex positions, and though as yet his painted subjects are still mostly tranquil, he made drawn studies of fighting nude men, one of the obsessions of the period in Florence. Another drawing is a portrait of a young woman that uses the three-quarter length pyramidal composition of the just-completed Mona Lisa, but still looks completely Raphaelesque. Another of Leonardo's compositional inventions, the pyramidal Holy Family, was repeated in a series of works that remain among his most famous easel paintings. There is a drawing by Raphael in the Royal Collection of Leonardo's lost Leda and the Swan, from which he adapted the contrapposto pose of his own Saint Catherine of Alexandria.[29] He also perfects his own version of Leonardo's sfumato modelling, to give subtlety to his painting of flesh, and develops the interplay of glances between his groups, which are much less enigmatic than those of Leonardo. But he keeps the soft clear light of Perugino in his paintings.[30]

Leonardo was more than thirty years older than Raphael, but Michelangelo, who was in Rome for this period, was just eight years his senior. Michelangelo already disliked Leonardo, and in Rome came to dislike Raphael even more, attributing conspiracies against him to the younger man.[31] Raphael would have been aware of his works in Florence, but in his most original work of these years, he strikes out in a different direction. His Deposition of Christ draws on classical sarcophagi to spread the figures across the front of the picture space in a complex and not wholly successful arrangement. Wöllflin detects in the kneeling figure on the right the influence of the Madonna in Michelangelo's Doni Tondo, but the rest of the composition is far removed from his style, or that of Leonardo. Though highly regarded at the time, and much later forcibly removed from Perugia by the Borghese, it stands rather alone in Raphael's work. His classicism would later take a less literal direction.[32]

The Ansidei Madonna, c. 1505, beginning to move on from Perugino

The Ansidei Madonna, c. 1505, beginning to move on from Perugino The Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1506, using Leonardo's pyramidal composition for subjects of the Holy Family.[33]

The Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1506, using Leonardo's pyramidal composition for subjects of the Holy Family.[33] Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1507, possibly echoes the pose of Leonardo's Leda

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1507, possibly echoes the pose of Leonardo's Leda Deposition of Christ, 1507, drawing from Roman sarcophagi

Deposition of Christ, 1507, drawing from Roman sarcophagi

Roman period

Vatican "Stanze"

In 1508, Raphael moved to Rome, where he resided for the rest of his life. He was invited by the new pope, Julius II, perhaps at the suggestion of his architect Donato Bramante, then engaged on St. Peter's Basilica, who came from just outside Urbino and was distantly related to Raphael.[34] Unlike Michelangelo, who had been kept lingering in Rome for several months after his first summons,[35] Raphael was immediately commissioned by Julius to fresco what was intended to become the Pope's private library at the Vatican Palace.[36] This was a much larger and more important commission than any he had received before; he had only painted one altarpiece in Florence itself. Several other artists and their teams of assistants were already at work on different rooms, many painting over recently completed paintings commissioned by Julius's loathed predecessor, Alexander VI, whose contributions, and arms, Julius was determined to efface from the palace.[37] Michelangelo, meanwhile, had been commissioned to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

.jpg)

This first of the famous "Stanze" or "Raphael Rooms" to be painted, now known as the Stanza della Segnatura after its use in Vasari's time, was to make a stunning impact on Roman art, and remains generally regarded as his greatest masterpiece, containing The School of Athens, The Parnassus and the Disputa. Raphael was then given further rooms to paint, displacing other artists including Perugino and Signorelli. He completed a sequence of three rooms, each with paintings on each wall and often the ceilings too, increasingly leaving the work of painting from his detailed drawings to the large and skilled workshop team he had acquired, who added a fourth room, probably only including some elements designed by Raphael, after his early death in 1520. The death of Julius in 1513 did not interrupt the work at all, as he was succeeded by Raphael's last Pope, the Medici Pope Leo X, with whom Raphael formed an even closer relationship, and who continued to commission him.[38] Raphael's friend Cardinal Bibbiena was also one of Leo's old tutors, and a close friend and advisor.

Raphael was clearly influenced by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling in the course of painting the room. Vasari said Bramante let him in secretly. The first section was completed in 1511 and the reaction of other artists to the daunting force of Michelangelo was the dominating question in Italian art for the following few decades. Raphael, who had already shown his gift for absorbing influences into his own personal style, rose to the challenge perhaps better than any other artist. One of the first and clearest instances was the portrait in The School of Athens of Michelangelo himself, as Heraclitus, which seems to draw clearly from the Sybils and ignudi of the Sistine ceiling. Other figures in that and later paintings in the room show the same influences, but as still cohesive with a development of Raphael's own style.[39] Michelangelo accused Raphael of plagiarism and years after Raphael's death, complained in a letter that "everything he knew about art he got from me", although other quotations show more generous reactions.[40]

These very large and complex compositions have been regarded ever since as among the supreme works of the grand manner of the High Renaissance, and the "classic art" of the post-antique West. They give a highly idealised depiction of the forms represented, and the compositions, though very carefully conceived in drawings, achieve "sprezzatura", a term invented by his friend Castiglione, who defined it as "a certain nonchalance which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless ...".[41] According to Michael Levey, "Raphael gives his [figures] a superhuman clarity and grace in a universe of Euclidian certainties".[42] The painting is nearly all of the highest quality in the first two rooms, but the later compositions in the Stanze, especially those involving dramatic action, are not entirely as successful either in conception or their execution by the workshop.

Stanza della Segnatura

Stanza della Segnatura The Mass at Bolsena, 1514, Stanza di Eliodoro

The Mass at Bolsena, 1514, Stanza di Eliodoro Deliverance of Saint Peter, 1514, Stanza di Eliodoro

Deliverance of Saint Peter, 1514, Stanza di Eliodoro The Fire in the Borgo, 1514, Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo, painted by the workshop to Raphael's design

The Fire in the Borgo, 1514, Stanza dell'incendio del Borgo, painted by the workshop to Raphael's design

Architecture

After Bramante's death in 1514, Raphael was named architect of the new St Peter's. Most of his work there was altered or demolished after his death and the acceptance of Michelangelo's design, but a few drawings have survived. It appears his designs would have made the church a good deal gloomier than the final design, with massive piers all the way down the nave, "like an alley" according to a critical posthumous analysis by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. It would perhaps have resembled the temple in the background of The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple.[43]

He designed several other buildings, and for a short time was the most important architect in Rome, working for a small circle around the Papacy. Julius had made changes to the street plan of Rome, creating several new thoroughfares, and he wanted them filled with splendid palaces.[44]

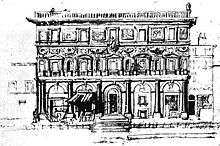

An important building, the Palazzo Branconio dell'Aquila for Leo's Papal Chamberlain Giovanni Battista Branconio, was completely destroyed to make way for Bernini's piazza for St. Peter's, but drawings of the façade and courtyard remain. The façade was an unusually richly decorated one for the period, including both painted panels on the top story (of three), and much sculpture on the middle one.[45]

The main designs for the Villa Farnesina were not by Raphael, but he did design, and decorate with mosaics, the Chigi Chapel for the same patron, Agostino Chigi, the Papal Treasurer. Another building, for Pope Leo's doctor, the Palazzo Jacopo da Brescia, was moved in the 1930s but survives; this was designed to complement a palace on the same street by Bramante, where Raphael himself lived for a time.[46]

The Villa Madama, a lavish hillside retreat for Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, later Pope Clement VII, was never finished, and his full plans have to be reconstructed speculatively. He produced a design from which the final construction plans were completed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. Even incomplete, it was the most sophisticated villa design yet seen in Italy, and greatly influenced the later development of the genre; it appears to be the only modern building in Rome of which Palladio made a measured drawing.[47]

Only some floor-plans remain for a large palace planned for himself on the new via Giulia in the rione of Regola, for which he was accumulating the land in his last years. It was on an irregular island block near the river Tiber. It seems all façades were to have a giant order of pilasters rising at least two storeys to the full height of the piano nobile, "a grandiloquent feature unprecedented in private palace design".[48]

Raphael asked Marco Fabio Calvo to translate Vitruvius's Four Books of Architecture into Italian; this he received around the end of August 1514. It is preserved at the Library in Munich with handwritten margin notes by Raphael.[49]

Antiquity

In about 1510, Raphael was asked by Bramante to judge contemporary copies of Laocoön and His Sons.[50] In 1515, he was given powers as Prefect over all antiquities unearthed within, or a mile outside the city.[51] Anyone excavating antiquities was required to inform Raphael within three days, and stonemasons were not allowed to destroy inscriptions without permission.[52] Raphael wrote a letter to Pope Leo suggesting ways of halting the destruction of ancient monuments, and proposed a visual survey of the city to record all antiquities in an organised fashion. The pope intended to continue to re-use ancient masonry in the building of St Peter's, also wanting to ensure that all ancient inscriptions were recorded, and sculpture preserved, before allowing the stones to be reused.[51]

According to Marino Sanuto the Younger's diary, in 1519 Raphael offered to transport an obelisk from the Mausoleum of August to St. Peter's Square for 90,000 ducats.[53] According to Marcantonio Michiel, Raphael's "youthful death saddened men of letters because he was not able to furnish the description and the painting of ancient Rome that he was making, which was very beautiful".[54] Raphael intended to make an archaeological map of ancient Rome but this was never executed.[55] Four archaeological drawings by the artist are preserved.[56]

Other painting projects

The Vatican projects took most of his time, although he painted several portraits, including those of his two main patrons, the popes Julius II and his successor Leo X, the former considered one of his finest. Other portraits were of his own friends, like Castiglione, or the immediate Papal circle. Other rulers pressed for work, and King Francis I of France was sent two paintings as diplomatic gifts from the Pope.[57] For Agostino Chigi, the hugely rich banker and papal treasurer, he painted the Triumph of Galatea and designed further decorative frescoes for his Villa Farnesina, a chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Pace and mosaics in the funerary chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. He also designed some of the decoration for the Villa Madama, the work in both villas being executed by his workshop.

One of his most important papal commissions was the Raphael Cartoons (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum), a series of 10 cartoons, of which seven survive, for tapestries with scenes of the lives of Saint Paul and Saint Peter, for the Sistine Chapel. The cartoons were sent to Brussels to be woven in the workshop of Pier van Aelst. It is possible that Raphael saw the finished series before his death—they were probably completed in 1520.[58] He also designed and painted the Loggie at the Vatican, a long thin gallery then open to a courtyard on one side, decorated with Roman-style grottesche.[59] He produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna. His last work, on which he was working up to his death, was a large Transfiguration, which together with Il Spasimo shows the direction his art was taking in his final years—more proto-Baroque than Mannerist.[60]

Triumph of Galatea, 1512, his only major mythology, for Chigi's villa (Villa Farnesina)

Triumph of Galatea, 1512, his only major mythology, for Chigi's villa (Villa Farnesina) Il Spasimo 1517, brings a new degree of expressiveness to his art. (Museo del Prado)

Il Spasimo 1517, brings a new degree of expressiveness to his art. (Museo del Prado) Transfiguration, 1520, unfinished at his death. (Pinacoteca Vaticana)

Transfiguration, 1520, unfinished at his death. (Pinacoteca Vaticana) The Holy Family, 1518 (Louvre)

The Holy Family, 1518 (Louvre)

Painting materials

Raphael painted several of his works on wood support (Madonna of the Pinks) but he also used canvas (Sistine Madonna) and he was known to employ drying oils such as linseed or walnut oils. His palette was rich and he used almost all of the then available pigments such as ultramarine, lead-tin-yellow, carmine, vermilion, madder lake, verdigris and ochres. In several of his paintings (Ansidei Madonna) he even employed the rare brazilwood lake, metallic powdered gold and even less known metallic powdered bismuth.[61][62]

Workshop

Vasari says that Raphael eventually had a workshop of fifty pupils and assistants, many of whom later became significant artists in their own right. This was arguably the largest workshop team assembled under any single old master painter, and much higher than the norm. They included established masters from other parts of Italy, probably working with their own teams as sub-contractors, as well as pupils and journeymen. We have very little evidence of the internal working arrangements of the workshop, apart from the works of art themselves, which are often very difficult to assign to a particular hand.[63]

The most important figures were Giulio Romano, a young pupil from Rome (only about twenty-one at Raphael's death), and Gianfrancesco Penni, already a Florentine master. They were left many of Raphael's drawings and other possessions, and to some extent continued the workshop after Raphael's death. Penni did not achieve a personal reputation equal to Giulio's, as after Raphael's death he became Giulio's less-than-equal collaborator in turn for much of his subsequent career. Perino del Vaga, already a master, and Polidoro da Caravaggio, who was supposedly promoted from a labourer carrying building materials on the site, also became notable painters in their own right. Polidoro's partner, Maturino da Firenze, has, like Penni, been overshadowed in subsequent reputation by his partner. Giovanni da Udine had a more independent status, and was responsible for the decorative stucco work and grotesques surrounding the main frescoes.[64] Most of the artists were later scattered, and some killed, by the violent Sack of Rome in 1527.[65] This did however contribute to the diffusion of versions of Raphael's style around Italy and beyond.

Vasari emphasises that Raphael ran a very harmonious and efficient workshop, and had extraordinary skill in smoothing over troubles and arguments with both patrons and his assistants—a contrast with the stormy pattern of Michelangelo's relationships with both.[66] However though both Penni and Giulio were sufficiently skilled that distinguishing between their hands and that of Raphael himself is still sometimes difficult,[67] there is no doubt that many of Raphael's later wall-paintings, and probably some of his easel paintings, are more notable for their design than their execution. Many of his portraits, if in good condition, show his brilliance in the detailed handling of paint right up to the end of his life.[68]

Other pupils or assistants include Raffaellino del Colle, Andrea Sabbatini, Bartolommeo Ramenghi, Pellegrino Aretusi, Vincenzo Tamagni, Battista Dossi, Tommaso Vincidor, Timoteo Viti (the Urbino painter), and the sculptor and architect Lorenzetto (Giulio's brother-in-law).[69] The printmakers and architects in Raphael's circle are discussed below. It has been claimed the Flemish Bernard van Orley worked for Raphael for a time, and Luca Penni, brother of Gianfrancesco and later a member of the First School of Fontainebleau, may have been a member of the team.[70]

Portraits

Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga, c. 1504

Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga, c. 1504 Portrait of Pope Julius II, c. 1512

Portrait of Pope Julius II, c. 1512 Portrait of Bindo Altoviti, c. 1514

Portrait of Bindo Altoviti, c. 1514 Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1515

Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1515

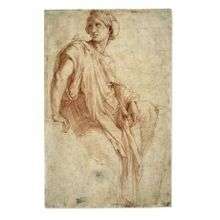

Drawings

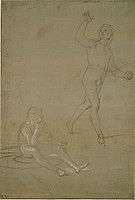

Raphael was one of the finest draftsmen in the history of Western art, and used drawings extensively to plan his compositions. According to a near-contemporary, when beginning to plan a composition, he would lay out a large number of stock drawings of his on the floor, and begin to draw "rapidly", borrowing figures from here and there.[72] Over forty sketches survive for the Disputa in the Stanze, and there may well have been many more originally; over four hundred sheets survive altogether.[73] He used different drawings to refine his poses and compositions, apparently to a greater extent than most other painters, to judge by the number of variants that survive: "... This is how Raphael himself, who was so rich in inventiveness, used to work, always coming up with four or six ways to show a narrative, each one different from the rest, and all of them full of grace and well done." wrote another writer after his death.[74] For John Shearman, Raphael's art marks "a shift of resources away from production to research and development".[75]

When a final composition was achieved, scaled-up full-size cartoons were often made, which were then pricked with a pin and "pounced" with a bag of soot to leave dotted lines on the surface as a guide. He also made unusually extensive use, on both paper and plaster, of a "blind stylus", scratching lines which leave only an indentation, but no mark. These can be seen on the wall in The School of Athens, and in the originals of many drawings.[76] The "Raphael Cartoons", as tapestry designs, were fully coloured in a glue distemper medium, as they were sent to Brussels to be followed by the weavers.

In later works painted by the workshop, the drawings are often painfully more attractive than the paintings.[77] Most Raphael drawings are rather precise—even initial sketches with naked outline figures are carefully drawn, and later working drawings often have a high degree of finish, with shading and sometimes highlights in white. They lack the freedom and energy of some of Leonardo's and Michelangelo's sketches, but are nearly always aesthetically very satisfying. He was one of the last artists to use metalpoint (literally a sharp pointed piece of silver or another metal) extensively, although he also made superb use of the freer medium of red or black chalk.[78] In his final years he was one of the first artists to use female models for preparatory drawings—male pupils ("garzoni") were normally used for studies of both sexes.[79]

Study for soldiers in this Resurrection of Christ, ca 1500.

Study for soldiers in this Resurrection of Christ, ca 1500. Red chalk study for the Villa Farnesina Three Graces

Red chalk study for the Villa Farnesina Three Graces Sheet with study for the Alba Madonna and other sketches

Sheet with study for the Alba Madonna and other sketches Developing the composition for a Madonna and Child

Developing the composition for a Madonna and Child

Printmaking

Raphael made no prints himself, but entered into a collaboration with Marcantonio Raimondi to produce engravings to Raphael's designs, which created many of the most famous Italian prints of the century, and was important in the rise of the reproductive print. His interest was unusual in such a major artist; from his contemporaries it was only shared by Titian, who had worked much less successfully with Raimondi.[80] A total of about fifty prints were made; some were copies of Raphael's paintings, but other designs were apparently created by Raphael purely to be turned into prints. Raphael made preparatory drawings, many of which survive, for Raimondi to translate into engraving.[81]

The most famous original prints to result from the collaboration were Lucretia, the Judgement of Paris and The Massacre of the Innocents (of which two virtually identical versions were engraved). Among prints of the paintings The Parnassus (with considerable differences)[82] and Galatea were also especially well known. Outside Italy, reproductive prints by Raimondi and others were the main way that Raphael's art was experienced until the twentieth century. Baviero Carocci, called "Il Baviera" by Vasari, an assistant who Raphael evidently trusted with his money,[83] ended up in control of most of the copper plates after Raphael's death, and had a successful career in the new occupation of a publisher of prints.[84]

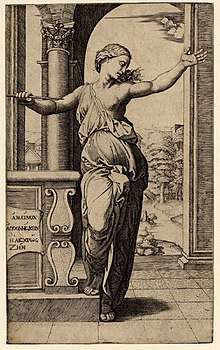

Drawing for a Sibyl in the Chigi Chapel.

Drawing for a Sibyl in the Chigi Chapel. The Massacre of the Innocents, engraving by ? Marcantonio Raimondi from a design by Raphael.[lower-alpha 3] The version "without fir tree".

The Massacre of the Innocents, engraving by ? Marcantonio Raimondi from a design by Raphael.[lower-alpha 3] The version "without fir tree". Judgement of Paris, still influencing Manet, who used the seated group in his most famous work.

Judgement of Paris, still influencing Manet, who used the seated group in his most famous work..jpg) Galatea, engraving after the fresco in the Villa Farnesina

Galatea, engraving after the fresco in the Villa Farnesina

Private life and death

From 1517 until his death, Raphael lived in the Palazzo Caprini, lying at the corner between piazza Scossacavalli and via Alessandrina in the Borgo, in rather grand style in a palace designed by Bramante.[85] He never married, but in 1514 became engaged to Maria Bibbiena, Cardinal Medici Bibbiena's niece; he seems to have been talked into this by his friend the cardinal, and his lack of enthusiasm seems to be shown by the marriage not having taken place before she died in 1520.[86] He is said to have had many affairs, but a permanent fixture in his life in Rome was "La Fornarina", Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker (fornaro) named Francesco Luti from Siena who lived at Via del Governo Vecchio.[87] He was made a "Groom of the Chamber" of the Pope, which gave him status at court and an additional income, and also a knight of the Papal Order of the Golden Spur. Vasari claims that he had toyed with the ambition of becoming a cardinal, perhaps after some encouragement from Leo, which also may account for his delaying his marriage.[86]

Raphael died on Good Friday (April 6, 1520), which was possibly his 37th birthday.[lower-alpha 4] Vasari says that Raphael had also been born on a Good Friday, which in 1483 fell on March 28,[lower-alpha 5] and that the artist died from exhaustion brought on by unceasing romantic interests while he was working on the Loggia.[89] Several other possibilities have been raised by later historians.[lower-alpha 6] In his acute illness, which lasted fifteen days, Raphael was composed enough to confess his sins, receive the last rites, and put his affairs in order. He dictated his will, in which he left sufficient funds for his mistress's care, entrusted to his loyal servant Baviera, and left most of his studio contents to Giulio Romano and Penni. At his request, Raphael was buried in the Pantheon.[90]

Raphael's funeral was extremely grand, attended by large crowds. According to a journal by Paris de Grassis,[lower-alpha 7] four cardinals dressed in purple carried his body, the hand of which was kissed by the Pope.[91] The inscription in Raphael's marble sarcophagus, an elegiac distich written by Pietro Bembo, reads: "Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was dying, feared herself to die."[lower-alpha 8]

- Self-portraits

Probable self-portrait drawing by Raphael in his teens

Probable self-portrait drawing by Raphael in his teens Self-portrait, Raphael in the background, from The School of Athens

Self-portrait, Raphael in the background, from The School of Athens Portrait of a Young Man, 1514, Lost during the Second World War. Possible self-portrait by Raphael

Portrait of a Young Man, 1514, Lost during the Second World War. Possible self-portrait by Raphael Possible Self-portrait with a friend, c. 1518

Possible Self-portrait with a friend, c. 1518

Critical reception

.jpg)

Raphael was highly admired by his contemporaries, although his influence on artistic style in his own century was less than that of Michelangelo. Mannerism, beginning at the time of his death, and later the Baroque, took art "in a direction totally opposed" to Raphael's qualities;[92] "with Raphael's death, classic art – the High Renaissance – subsided", as Walter Friedländer put it.[93] He was soon seen as the ideal model by those disliking the excesses of Mannerism:

the opinion ...was generally held in the middle of the sixteenth century that Raphael was the ideal balanced painter, universal in his talent, satisfying all the absolute standards, and obeying all the rules which were supposed to govern the arts, whereas Michelangelo was the eccentric genius, more brilliant than any other artists in his particular field, the drawing of the male nude, but unbalanced and lacking in certain qualities, such as grace and restraint, essential to the great artist. Those, like Dolce and Aretino, who held this view were usually the survivors of Renaissance Humanism, unable to follow Michelangelo as he moved on into Mannerism.[94]

Vasari himself, despite his hero remaining Michelangelo, came to see his influence as harmful in some ways, and added passages to the second edition of the Lives expressing similar views.[95]

Raphael's compositions were always admired and studied, and became the cornerstone of the training of the Academies of art. His period of greatest influence was from the late 17th to late 19th centuries, when his perfect decorum and balance were greatly admired. He was seen as the best model for the history painting, regarded as the highest in the hierarchy of genres. Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses praised his "simple, grave, and majestic dignity" and said he "stands in general foremost of the first [i.e., best] painters", especially for his frescoes (in which he included the "Raphael Cartoons"), whereas "Michael Angelo claims the next attention. He did not possess so many excellences as Raffaelle, but those he had were of the highest kind..." Echoing the sixteenth-century views above, Reynolds goes on to say of Raphael:

The excellency of this extraordinary man lay in the propriety, beauty, and majesty of his characters, his judicious contrivance of his composition, correctness of drawing, purity of taste, and the skilful accommodation of other men's conceptions to his own purpose. Nobody excelled him in that judgment, with which he united to his own observations on nature the energy of Michael Angelo, and the beauty and simplicity of the antique. To the question, therefore, which ought to hold the first rank, Raffaelle or Michael Angelo, it must be answered, that if it is to be given to him who possessed a greater combination of the higher qualities of the art than any other man, there is no doubt but Raffaelle is the first. But if, according to Longinus, the sublime, being the highest excellence that human composition can attain to, abundantly compensates the absence of every other beauty, and atones for all other deficiencies, then Michael Angelo demands the preference.[96]

Reynolds was less enthusiastic about Raphael's panel paintings, but the slight sentimentality of these made them enormously popular in the 19th century: "We have been familiar with them from childhood onwards, through a far greater mass of reproductions than any other artist in the world has ever had..." wrote Wölfflin, who was born in 1862, of Raphael's Madonnas.[97]

In Germany, Raphael had an immense influence on religious art of the Nazarene movement and Düsseldorf school of painting in the 19th century. In contrast, in England the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood explicitly reacted against his influence (and that of his admirers such as Joshua Reynolds), seeking to return to styles that pre-dated what they saw as his baneful influence. According to a critic whose ideas greatly influenced them, John Ruskin:

The doom of the arts of Europe went forth from that chamber [the Stanza della Segnatura], and it was brought about in great part by the very excellencies of the man who had thus marked the commencement of decline. The perfection of execution and the beauty of feature which were attained in his works, and in those of his great contemporaries, rendered finish of execution and beauty of form the chief objects of all artists; and thenceforward execution was looked for rather than thought, and beauty rather than veracity.

And as I told you, these are the two secondary causes of the decline of art; the first being the loss of moral purpose. Pray note them clearly. In mediæval art, thought is the first thing, execution the second; in modern art execution is the first thing, and thought the second. And again, in mediæval art, truth is first, beauty second; in modern art, beauty is first, truth second. The mediæval principles led up to Raphael, and the modern principles lead down from him.[98]

By 1900, Raphael's popularity was surpassed by Michelangelo and Leonardo, perhaps as a reaction against the etiolated Raphaelism of 19th-century academic artists such as Bouguereau.[99] Although art historian Bernard Berenson in 1952 termed Raphael the "most famous and most loved" master of the High Renaissance,[100] art historians Leopold and Helen Ettlinger say that the Raphael's lesser popularity in the 20th century is made obvious by "the contents of art library shelves ... In contrast to volume upon volume that reproduce yet again detailed photographs of the Sistine Ceiling or Leonardo's drawings, the literature on Raphael, particularly in English, is limited to only a few books".[99] They conclude, nonetheless, that "of all the great Renaissance masters, Raphael's influence is the most continuous."[101]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- He is said to have been born on Good Friday (March 28, 1483), but is stated to have been born on the same date as his death on the inscription of his tomb (he died three hours after the Ave Maria of Good Friday). Both birth dates cannot be true.[4]

- After a visit to Verrocchio's workshop, Santi recorded that both Perugino and Leonardo da Vinci were present, and seems to have viewed them as being at an equivalent skill level. After Leonardo left for Milan, Santi chose Perugino from one of two available artists to teach his son.[15]

- The bridge in the background is the Pons Fabricius.[56]

- Raphael's age at death is debated by some, with Michiel asserting that Raphael died at 34, while Pandolfo Pico and Girolamo Lippomano arguing that he died at 33.[88]

- Whereas Michiel said he died on his birthday. Art historian John Shearman addressed this apparent discrepancy: "The time of death can be calculated from the convention of counting from sundown, which Michaelis puts at 6.36 on Friday 6 April, plus half-an-hour to Ave Maria, plus three hours, that is, soon after 10.00 pm. The coincidence noted between the birth-date and death-date is usually thought in this case (since it refers to the Friday and Saturday in Holy Week, the movable feast rather than the day of the month) to fortify the argument that Raphael was also born on Good Friday, i.e., 28 March 1483. But there is a notable ambiguity in Michiel's note, not often noticed: Morse ... Venerdi Santo venendo il Sabato, giorno della sua Nativita, may also be taken to mean that his birthday was on Saturday, and in that case the awareness could as well be the date, thus producing a birth-date of 7 April 1483."[88]

- Bufarale (1915) "diagnosed pneumonia or a military fever" while Portigliotti suggested pulmonary disease. Joannides stated that "Raphael died of over-work."[88]

- Cited by Jean-M.-Vincent Audin, although there is some uncertainty as to the journal's existence.[91]

- The original (in Latin): "Ille hic est Raffael, timuit quo sospite vinci, rerum magna parens et moriente mori".

Citations

- Jones and Penny, p. 171. The portrait of Raphael is probably "a later adaptation of the one likeness which all agree on": that in The School of Athens, vouched for by Vasari.

- Variants also include Raffaello Santi, Raffaello da Urbino or Rafael Sanzio da Urbino. The surname Sanzio derives from the latinization of the Italian Santi into Santius. He normally signed documents as Raphael Urbinas – a latinized form. Gould:207

- Jones and Penny, p. 1 and 246.

- Salmi et al. 1969, pp. 585, 597.

- On Neoplatonism, see Chapter 4, "The Real and the Imaginary" Archived December 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, in Kleinbub, Christian K., Vision and the Visionary in Raphael, 2011, Penn State Press, ISBN 0271037040, 9780271037042

- See, for example Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1982). A World History of Art. London: Macmillan Reference Books. p. 357. ISBN 9780333235836. OCLC 8828368.

- Vasari, pp. 208, 230 and passim.

- Osborne, June. Urbino: The Story of a Renaissance City. p. 39 on the population, as a "few thousand" at most; even today it is only 15,000 without the students of the University.

- Jones and Penny, pp. 1–2

- Vasari:207 & passim

- Jones & Penny:204

- Vasari, at the start of the Life. Jones & Penny:5

- Ashmolean Museum "Image". z.about.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007.

- Jones and Penny: 4–5, 8 and 20

- Salmi et al. 1969, pp. 11–12.

- Simone Fornari in 1549–50, see Gould:207

- Jones & Penny:8

- contrasting him with Leonardo and Michelangelo in this respect. Wölfflin:73

- Jones and Penny:17

- Jones & Penny:2–5

- Ettlinger & Ettlinger:19

- Ettlinger & Ettlinger:20

- It was later seriously damaged during an earthquake in 1789.

- Jones and Penny:5–8

- One surviving preparatory drawing appears to be mostly by Raphael; quotation from Vasari by – Jones and Penny:20

- Ettlinger & Ettlinger:25–27

- Gould:207-8

- Jones and Penny:5

- National Gallery, London Jones & Penny:44

- Jones & Penny:21–45

- Vasari, Michelangelo:251

- Jones & Penny:44–47, and Wöllflin:79–82

- "Image". szepmuveszeti.hu. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012.

- Jones & Penny:49, differing somewhat from Gould:208 on the timing of his arrival

- Vasari:247

- Julius was no great reader—an inventory compiled after his death has a total of 220 books, large for the time, but hardly requiring such a receptacle. There was no room for bookcases on the walls, which were in cases in the middle of the floor, destroyed in the 1527 Sack of Rome. Jones & Penny:4952

- Jones & Penny:49

- Jones & Penny:49–128

- Jones & Penny:101–105

- Blunt:76, Jones & Penny:103-5

- Book of the Courtier 1:26 The whole passage Archived December 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Levey, Michael; Early Renaissance, p.197 ,1967, Penguin

- Jones & Penny:215–218

- Jones & Penny:210–211

- Jones & Penny:221–222

- Jones & Penny:219–220

- Jones and Penny:226–234; Raphael left a long letter describing his intentions to the Cardinal, reprinted in full on pp.247–8

- Jones & Penny:224(quotation)-226

- Salmi et al. 1969, pp. 572–73, 588.

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 110.

- Jones & Penny:205 The letter may date from 1519, or before his appointment

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 582.

- Salmi et al. 1969, pp. 569, 582.

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 570.

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 574.

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 579.

- One, a portrait of Joanna of Aragon, Queen consort of Naples, for which Raphael sent an assistant to Naples to make a drawing, and probably left most of the painting to the workshop. Jones & Penny:163

- Jones & Penny:133–147

- Jones & Penny:192–197

- Jones & Penny:235–246, though the relationship of Raphael to Mannerism, like the definition of Mannerism itself, is much debated. See Craig Hugh Smyth, Mannerism & Maniera, 1992, IRSA Vienna, ISBN 3-900731-33-0

- Roy, A., Spring, M., Plazzotta, C. 'Raphael's Early Work in the National Gallery: Paintings before Rome'. National Gallery Technical Bulletin Vol 25, pp 4–35

- Italian painters Archived March 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at ColourLex

- Jones and Penny:146–147, 196–197, and Pon:82–85

- Jones and Penny:147, 196

- Vasari, Life of Polidoro online in English Archived April 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Maturino for one is never heard of again

- Vasari:207 & 231

- See for example, the Raphael Cartoons

- Jones & Penny:163–167 and passim

- The direct transmission of training can be traced to some surprising figures, including Brian Eno, Tom Phillips and Frank Auerbach

- Vasari (full text in Italian) pp197-8 & passim Archived December 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine; see also Getty Union Artist Name List Archived December 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine entries

- "Lucretia". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on April 29, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Giovanni Battista Armenini (1533–1609) De vera precetti della pittura(1587), quoted Pon:115

- Jones & Penny:58 & ff; 400 from Pon:114

- Ludovico Dolce (1508–68), from his L'Aretino of 1557, quoted Pon:114

- quoted Pon:114, from lecture on The Organization of Raphael's Workshop, pub. Chicago, 1983

- Not surprisingly, photographs do not show these well, if at all. Leonardo sometimes used a blind stylus to outline his final choice from a tangle of different outlines in the same drawing. Pon:106–110.

- Lucy Whitaker, Martin Clayton, The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection; Renaissance and Baroque, p.84, Royal Collection Publications, 2007, ISBN 978-1-902163-29-1

- Pon:104

- National Galleries of Scotland Archived May 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Pon:102. See also a lengthy analysis in: Landau:118 ff

- The enigmatic relationship is discussed at length by both Landau and Pon in her Chapters 3 and 4.

- Pon:86–87 lists them

- "Il Baviera" may mean "the Bavarian"; if he was German, as many artists in Rome were, this would have been helpful during the 1527 Sack; Marcantonio had many printing-plates looted from him. Jones and Penny:82, see also Vasari

- Pon:95–136 & passim; Landau:118–160, and passim

- Gigli (1992), p. 46

- Vasari:230–231

- Art historians and doctors debate whether the right hand on the left breast in La Fornarina reveal a cancerous breast tumour detailed and disguised in a classic pose of love. "The Portrait of Breast Cancer and Raphael's La Fornarina", The Lancet, December 21, 2002/December 28, 2002.

- Shearman: 573.

- Salmi et al. 1969, p. 598.

- Vasari:231

- Salmi et al. 1969, pp. 598–99.

- Chastel André, Italian Art, p. 230, 1963, Faber

- Walter Friedländer, Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting, p.42 (Schocken 1970 edn.), 1957, Columbia UP

- Blunt:76

- See Jones & Penny:102-4

- The 1772 Discourse Online text of Reynold's Discourses Archived 2007-02-27 at the Wayback Machine The whole passage is worth reading.

- Wölfflin:82,

- John Ruskin (1853), Pre-Raphaelitism, p. 127 online at Project Gutenburg Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Ettlinger & Ettlinger:11

- Berenson, Bernard, Italian Painters of the renaissance, Vol 2 Florentine and Central Italian Schools, Phaidon 1952 (refs to 1968 ed), p.94

- Ettlinger & Ettlinger:230

References

- Blunt, Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450–1660, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- Gould, Cecil, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- Ettlinger, Leopold D., and Helen S. Ettlinger, Raphael, Oxford: Phaidon, 1987, ISBN 0714823031

- Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny, Raphael, Yale, 1983, ISBN 0-300-03061-4

- Landau, David in:David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Pon, Lisa, Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi, Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print, 2004, Yale UP, ISBN 978-0-300-09680-4

- Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company.

- Shearman, John; Raphael in Early Modern Sources 1483–1602, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09918-5

- Vasari, Life of Raphael from the Lives of the Artists, edition used: Artists of the Renaissance selected & ed Malcolm Bull, Penguin 1965 (page nos from BCA edn, 1979)

- Wölfflin, Heinrich; Classic Art; An Introduction to the Renaissance, 1952 in English (1968 edition), Phaidon, New York.

- Gigli, Laura (1992). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Borgo (II). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori. ISSN 0393-2710.

Further reading

- The standard source of biographical information is now: V. Golzio, Raffaello nei documenti nelle testimonianze dei contemporanei e nella letturatura del suo secolo, Vatican City and Westmead, 1971

- The Cambridge Companion to Raphael, Marcia B. Hall, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-80809-X,

- New catalogue raisonné in several volumes, still being published, Jürg Meyer zur Capellen, Stefan B. Polter, Arcos, 2001–2008

- Raphael. James H. Beck, Harry N. Abrams, 1976, LCCN 73-12198, ISBN 0-8109-0432-2

- Raphael, Pier Luigi De Vecchi, Abbeville Press, 2003. ISBN 0789207702

- Raphael, Bette Talvacchia, Phaidon Press, 2007. ISBN 9780714847863

- Raphael, John Pope-Hennessy, New York University Press, 1970, ISBN 0-8147-0476-X

- Raphael: From Urbino to Rome; Hugo Chapman, Tom Henry, Carol Plazzotta, Arnold Nesselrath, Nicholas Penny, National Gallery Publications Limited, 2004, ISBN 1-85709-999-0 (exhibition catalogue)

- The Raphael Trail: The Secret History of One of the World's Most Precious Works of Art; Joanna Pitman, 2006. ISBN 0091901715

- Raphael – A Critical Catalogue of his Pictures, Wall-Paintings and Tapestries, catalogue raisonné by Luitpold Dussler published in the United States by Phaidon Publishers, Inc., 1971, ISBN 0-7148-1469-5 (out of print, but there is an online version here )

- Wolk-Simon, Linda. (2006). Raphael at the Metropolitan: The Colonna Altarpiece. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588391889.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raffaello Sanzio. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Raphael |

- 120 paintings by or after Raphael at the Art UK site

- Raphael at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Raphael Research Resource from the National Gallery, London

- V&A London online feature on the Raphael Cartoons

- Ten drawings and three paintings from the Royal Collection

- Web Gallery of Art

- Most of the Raphael/Raimondi prints from the San Francisco Museums

- Raphael Project/Raffael Projekt

- Website of Teylers Museum on the provenance of the Raphael drawings in the museum's collection.

- Birthplace Museum of Raphael, Urbino, on the Artist's Studio Museum Network website

- Mobilier national (France) collection of tapestries

- Raphael Santi at ColourLex.

- Raphael at the National Gallery of Art

- Guide to the Raphael Spurious Letters undated at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center