Women in Italy

Women in Italy refers to females who are from (or reside in) Italy. The legal and social status of Italian women has undergone rapid transformations and changes during the past decades. This includes family laws, the enactment of anti-discrimination measures, and reforms to the penal code (in particular with regard to crimes of violence against women).[3]

| |

| Gender Inequality Index-2015[1] | |

|---|---|

| Value | 0.085 |

| Rank | 16th |

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 4 |

| Women in parliament | 30.1% |

| Females over 25 with secondary education | 79.1% (M: 83.3%) |

| Women in labour force | 54% (M: 74%) |

| Global Gender Gap Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.707 (2020) |

| Rank | 76th out of 149 |

History

For the Roman period, see Women in Ancient Rome.

Women in Pre-modern Italy

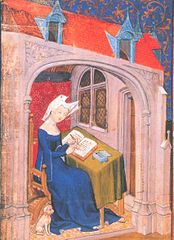

During the Middle ages, Italian women were considered to have very few social powers and resources, although some widows inherited ruling positions from their husbands (such in the case of Matilde of Canossa). Educated women could find opportunities of leadership only in religious convents (such as Clare of Assisi and Catherine of Siena).

The Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) challenged conventional customs from the Medieval period. Women were still confined to the roles of "monaca, moglie, serva, cortigiana" ("nun, wife, servant, courtesan").[4] However, literacy spread among upper-class women in Italy and a growing number of them stepped out into the secular intellectual circles. Venetian-born Christine de Pizan wrote The City of Ladies in 1404, and in it she described women's gender as having no innate inferiority to men's, although being born to serve the other sex. Some women were able to gain an education on their own, or received tutoring from their father or husband.

Lucrezia Tornabuoni in Florence; Veronica Gambara at Correggio; Veronica Franco and Moderata Fonte in Venice; and Vittoria Colonna in Rome were among the renowned women intellectuals of the time. Powerful women rulers of the Italian Renaissance, such as Isabella d'Este, Catherine de' Medici, or Lucrezia Borgia, combined political skill with cultural interests and patronage. Unlike her peers, Isabella di Morra (an important poet of the time) was kept a virtual prisoner in her own castle and her tragic life makes her a symbol of female oppression.[5]

By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Italian women intellectuals were embraced by contemporary culture as learned daughters, wives, mothers, and equal partners in their household.[6] Among them were composers Francesca Caccini and Leonora Baroni, and painter Artemisia Gentileschi. Outside the family setting, Italian women continued to find opportunities in the convent, and now increasingly also as singers in the theatre (Anna Renzi—described as the first diva in the history of opera—and Barbara Strozzi are two examples). In 1678, Elena Cornaro Piscopia was the first woman in Italy to receive an academical degree, in philosophy, from the University of Padua.

In the 18th-century, the Enlightenment offered for the first time to Italian women (such as Laura Bassi, Cristina Roccati, Anna Morandi Manzolini, and Maria Gaetana Agnesi) the possibility to engage in the fields of science and mathematics. Italian sopranos and prime donne continued to be famous all around Europe, such as Vittoria Tesi, Caterina Gabrielli, Lucrezia Aguiari, and Faustina Bordoni. Other notable women of the period include painter Rosalba Carriera and composer Maria Margherita Grimani.

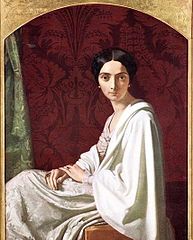

Women of the Risorgimento

The Napoleonic Age and the Italian Risorgimento offered for the first time to Italian women the opportunity to be politically engaged.[7] In 1799 in Naples, poet Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel was executed as one of the protagonists of the short-lived Parthenopean Republic. In the early 19th century, some of the most influential salons where Italian patriots, revolutionaries, and intellectuals were meeting were run by women, such as Bianca Milesi Mojon, Clara Maffei, Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso, and Antonietta De Pace. Some women even distinguished themselves in the battlefield, such as Anita Garibaldi (the wife of Giuseppe Garibaldi), Rosalia Montmasson (the only woman to have joined the Expedition of the Thousand), Giuseppina Vadalà, who along with her sister Paolina led an anti-Bourbon revolt in Messina in 1848, and Giuseppa Bolognara Calcagno, who fought as a soldier in Garibaldi's liberation of Sicily.

The Kingdom of Italy (1861–1925)

Between 1861 and 1925, women were not permitted to vote in the new Italian state. In 1864, Anna Maria Mozzoni triggered a widespread women's movement in Italy, through the publication of Woman and her social relationships on the occasion of the revision of the Italian Civil Code (La donna e i suoi rapporti sociali in occasione della revisione del codice italiano). In 1868, Alaide Gualberta Beccari began publishing the journal "Women" in Padua.

A growing percentage of young women were now employed in factories, but were excluded from political life and were particularly exploited. Under the influence of socialist leaders, such as Anna Kuliscioff, women became active in the constitution of the first Labour Unions. In 1902, the first law to protect the labour of women (and children) was approved; it forbade them working in mines and limited women to twelve hours of work per day.

By the 1880s, women were making inroads into higher education. In 1877, Ernestina Puritz Manasse-Paper was the first woman to receive a university degree in modern Italy, in medicine, and in 1907 Rina Monti was the first female professor in an Italian University.

The most famous women of the time were actresses Eleonora Duse, Lyda Borelli, and Francesca Bertini; writers Matilde Serao, Sibilla Aleramo, Carolina Invernizio, and Grazia Deledda (who won the 1926 Nobel Prize in Literature); sopranos Luisa Tetrazzini and Lina Cavalieri; and educator Maria Montessori.

Maria Montessori was the most amazing woman at this time as she was the first Italian physician, and began Montessori education which is still used today. She was part of Italy's change to further give women rights, and she was an influence to educators in Italy and around the globe.

Under the Fascist regime (1925–1945)

Even before the March on Rome, despite the difficulties of the revolutionary period (Biennio Rosso), there were still a hundred militant fascist women, while in Monza the first women's fascist group was founded on 12 May 1920.

The first point of the fascist Manifesto of Piazza Sansepolcro asked "vote and eligibility for women", the law of 22 November 1925 established in fact the female vote in local elections.

In 1938, moreover, Mussolini even tried to ensure the representation of women in the Chamber of Fasci and Corporations, but the king Vittorio Emanuele III opposed the idea. Which makes understand by which environments arrived the greatest resistances to overcoming the old social and cultural patterns. The truth is that fascism intended to offer women "a third way between the oratory and the house" . "The nationalization of all the individual destinies called each person, man or woman, to participate actively in the construction of the greatness of their country, "as Annalisa Terranova wrote in his "Camiciette Nere". Notable for that time were the rules that established the ban of the dismissal in case of pregnancy and a waiting period for maternity.

More than only this laws: challenging the prevailing moralism, fascism will bring to stadiums thousands of young girls, in an attempt of collective mobilization that basically created something from nothing — women's sports — entirely absent in Italy before 1922.

In 1935, G.A. Chiurco is even more explicit: "The fascist state can't conceive the woman locked in her house." Not always, unfortunately, this awareness came to dismantle the old pre — fascist prejudices, even though it is thanks to the regime's effort if in the Olympics of 1936 Italy conquered a historic gold medal in the 80 meters hurdles with the athlete Ondina Valla, who celebrated with a fascist salute from the top step of the podium. Valla was then received with full honors in Venice Square by Mussolini.

The young Italian women of the regime "were no longer attached to the skirt of their mothers and had managed to stop with the imprisonment of older sisters, which, at their age, came out of the house only in mom's or aunt's company," acknowledged the anti-fascist Victoria de Grazia.

And last but not least is remarkable experience of the SAF (Servizio Ausiliario Femminile): the first female army in the world wanted by Mussolini during the period of the Italian Social Republic (1943-1945).

The Italian Republic (1945–present)

After WW2, women were given the right to vote in national elections and to be elected to government positions. The new Italian Constitution of 1948 affirmed that women had equal rights. It was not however until the 1970s that women in Italy scored some major achievements with the introduction of laws regulating divorce (1970), abortion (1978), and the approval in 1975 of the new family code.

Famous women of the period include politicians Nilde Iotti, Tina Anselmi, and Emma Bonino; actresses Anna Magnani, Sofia Loren, and Gina Lollobrigida; soprano Renata Tebaldi; ballet dancer Carla Fracci; costume designer Milena Canonero; sportwomen Sara Simeoni, Deborah Compagnoni, Valentina Vezzali, and Federica Pellegrini; writers Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, Alda Merini, and Oriana Fallaci; architect Gae Aulenti; scientist and 1986 Nobel Prize winner Rita Levi-Montalcini; astrophysicist Margherita Hack; astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti; pharmacologist Elena Cattaneo; and CERN Director-General Fabiola Gianotti.

Issues in present time

Today, women have the same legal rights as men in Italy, and have mainly the same job, business, and education opportunities.[8]

Reproductive rights and health

The maternal mortality rate in Italy is 4 deaths/100,000 live births (as of 2010), one of the lowest in the world.[9] The HIV/AIDS rate is 0.3% of adults (aged 15–49)—estimates of 2009.[10]

Abortion laws were liberalized in 1978: abortion is usually legal during the first trimester of pregnancy, while at later stages of pregnancy it is permitted only for medical reasons, such as problems with the health of the mother or fetal defects.[11] However, in practice it is often difficult to obtain an abortion, due to the rising number of doctors and nurses who refuse to perform an abortion based on moral/religious opposition, which they are legally allowed to do.[3][12]

Marriage and family

Divorce in Italy was legalized in 1970. Obtaining a divorce in Italy is still a lengthy and complicated process, requiring a period of legal separation before it can be granted,[13] although the period of separation has been reduced in 2015.[14] Adultery was decriminalized in 1969, after the Constitutional Court of Italy struck down the law as unconstitutional, because it discriminated against women.[15] In 1975, Law No. 151/1975 provided for gender equality within marriage, abolishing the legal dominance of the husband.[3][16]

Unmarried cohabitation in Italy and births outside of marriage are not as common as in many other Western countries, but in recent years they have increased. In 2017, 30.9% of all births were outside of marriage, but there are significant differences by regions, with unmarried births being more common in the North than in the South.[17] Italy has a low total fertility rate, with 1.32 children born/woman (in 2017),[18] which is below the replacement rate of 2.1. Of women born in 1968, 20% stayed childless.[19] In the EU, only Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Poland, and Portugal have a lower total fertility rate than Italy.[20]

Female education

Women in Italy tend to have highly favorable results, and mainly excel in secondary and tertiary education.[8] Ever since the Italian economic miracle, the literacy rate of women as well as university enrolment has gone up dramatically in Italy.[8] The literacy rate of women is only slightly lower than that of men (as of 2011, the literacy rate was 98.7% female and 99.2% male).[21] Sixty percent of Italian university graduates are female, and women are excellently represented in all academic subjects, including mathematics, information technology, and other technological areas which are usually occupied by males.[8]

Work

Female standards at work are generally of a high quality and professional, but are not as good as in education.[8] The probability of a woman getting employed is mainly related to her qualifications, and 80% of women who graduate from university go on to seek jobs.[8] Women in Italy face a number of challenges. Although gender roles are not as strict as they have been in the past, sexual and domestic abuse is still quite prevalent in Italy. On average, women do 3.7 hours more housework than men. Men make up the majority of the parliament (women represent less than a third of the parliament).[22] Additionally, women in Italy are not adequately represented in the workforce, as Italy has one of the lowest rates of employment for women of the countries within the European Union. Women's employment rate (for ages 15–64) is 47.8% (in 2015), compared to 66.5% for men.[23] Many women are still frequently expected to stay at home and care for the house and children, as opposed to earning a salary and becoming a breadwinner, and few senior managerial positions are held by women. Furthermore, there are unequal standards and expectations for the few women who actually make it into a professional setting. For example, 9% of working Italian mothers have lost their jobs due to pregnancy. Although legislation protects pregnant women (in accordance with EU directives), the social climate still does not reflect full equality, nor does it protect against abuse. An infamous practice in Italy is that of "white resignation" (dimissione in bianco), whereby female employees are asked as condition for their employment or promotion to sign undated resignation papers, which are kept by the employer who adds a date on them when the woman is pregnant so that she "resigns" at that date.[24] Social views, particularly in Southern Italy, remain quite conservative. Italian lawmakers are working to further protect and support women as they break gender stereotypes and join the workforce, but complete cultural change is slow.[25][26][27] Nevertheless, the proportion of women in the workforce has increased in recent years: according to World Bank, in 1990 women made up 36.3% of the labour force, while by 2016 they made up 42.1%.[28]

Pay

Women holding white collar, high level, or office jobs tend to get paid the same as men, but women with blue collar or manual positions are paid 1/3 less than their male counterparts.[8]

Culture and society

Today, there is a growing acceptance of gender equality, and people (especially in the North[29]) tend to be far more liberal towards women getting jobs, going to university, and doing stereotypically male things. However, in some parts of society, women are still stereotyped as being simply housewives and mothers, also reflected in the fact of a higher-than-EU average female unemployment.[30]

Ideas about the appropriate social behaviour of women have traditionally had a very strong impact on the state institutions, and it has long been held that a woman's 'honour' is more important then her well-being. Until the 1970s, rape victims were often expected and forced to marry their rapist. In 1965, Franca Viola, a 17-year-old girl from Sicily, created a sensation when she refused to marry the man who kidnapped and raped her. In refusing this "rehabilitating marriage" to the perpetrator, she went against the traditional social norms of the time which dictated such a solution. Until 1981, the Criminal Code itself supported this practice, by exonerating the rapist who married his victim.[31] The Franca Viola incident was made into a movie called La moglie più bella.

In 2000 female toplessness was officially legalized (in a nonsexual context) in all public beaches and swimming pools throughout Italy (unless otherwise specified by region, province or municipality by-laws) in 20 March 2000, when the Supreme Court of Cassation (through sentence No. 3557) determined that the exposure of the nude female breast, after several decades, was considered a "commonly accepted behavior", and therefore, "entered into the social costume".[32]

In more recent times the media, particularly TV shows, have been accused of promoting sexist stereotypes. In 2017, one talk-show of a state-owned broadcaster was cancelled after accusations that it promoted discriminatory views of women.[33]

Violence against women

In 2020, statistics showed that 8 out of 10 female victims murders were murdered by a current or previous partner. A third of women were exposed to violence.[34] From 2000 to 2012, 2200 women were killed and 75% of those were murdered by a former or current partner. This represented about one murder every two days. A 2012 United Nations report noted that 90% of women who were raped or abused in Italy did not report the crime to police.[35]

In recent years, Italy has taken steps to address violence against women and domestic violence, including creating Law No. 38 of 23 April 2009.[16] Italy has also ratified the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence.[36]

Until the 1970s, in some regions rape victims were often expected and forced to marry their rapist. In 1965, Franca Viola, a 17-year-old girl from Sicily, created a sensation when she refused to marry the man who kidnapped and raped her. In refusing this "rehabilitating marriage" to the perpetrator, she went against the traditional social norms of the time which dictated such a solution. In 1976 in the Supreme Court of Italy ruled that "the spouse who compels the other spouse to carnal knowledge by violence or threats commits the crime of carnal violence" [meaning rape] ("commette il delitto di violenza carnale il coniuge che costringa con violenza o minaccia l’altro coniuge a congiunzione carnale").[37][38][39] As well, in 1981, Italy repealed Article 544.[40]

Traditionally, as in other Mediterranean-European areas, the concept of family honour was very important in Italy. Indeed, until 1981, the Criminal Code provided for mitigating circumstances for so-called honour killings.[41] Traditionally, honour crimes used to be more prevalent in Southern Italy.[42][43]

Gallery

Matilde di Canossa

Matilde di Canossa

_-_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg)

Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso

Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso

_-_Anna_Kuliscioff_a_Firenze_(1908).jpg)

- Francesca Saverio Cabrini

Bibliography

- Aa.Vv. Il Novecento delle Italiane. Una storia ancora da raccontare. Roma: Editori Riuniti, 2001.

- Addis Saba, Marina. Partigiane. Le donne della resistenza. Milano: Mursia, 1998.

- Bellomo, Manlio. La condizione giuridica della donna in Italia: vicende antiche e moderne. Torino: Eri, 1970.

- Boneschi, Marta. Di testa loro. Dieci italiane che hanno fatto il Novecento. Milano: Monadori, 2002.

- Bruni, Emanuela, Patrizia Foglia, Marina Messina (a cura di). La donna in Italia 1848-1914. Unite per unire. Cinisello Balsamo, Milano: Silvana, 2011.

- Craveri, Benedetta. Amanti e regine. Il potere delle donne. Milano: Adelphi, 2005.

- Dal Pozzo, Giuliana. Le donne nella storia d'Italia. Torino: Teti, 1969.

- De Giorgio, Michela. Le italiane dall'Unità a oggi: modelli cultuali e comportamenti sociali. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 1992.

- Drago, Antonietta. Donne e amori del Risorgimento. Milano: Palazzi, 1960.

- Grazia, Victoria de. How Fascism Ruled Women: Italy, 1922-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Matthews-Grieco, Sara F. (a cura di). Monaca, moglie, serva, cortigiana: vita e immagine delle donne tra Rinascimento e Controriforma. Firenze: Morgana, 2001.

- Migliucci, Debora. Breve storia delle conquiste femminili nel lavoro e nella società italiana. Milano: Camera del lavoro metropolitana, 2007.

- Roccella, Eugenia, e Lucetta Scaraffa. Italiane (3 voll.). Roma: Dipartimento per le pari opportunita', 2003.

- Rossi-Doria, Anna (a cura di). A che punto è la storia delle donne in Italia. Roma: Viella, 2003.

- Willson, Perry. Women in Twentieth-Century Italy. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

See also

- Women in Ancient Rome

References

- "Gender Inequality Index". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "The Global Gender Gap Report 2020".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sara F. Matthews-Grieco (a cura di), Monaca, moglie, serva, cortigiana: vita e immagine delle donne tra Rinascimento e Controriforma (Firenze: Morgana, 2001).

- Gaetana Marrone, Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies: A-J, Taylor & Francis, 2007, p. 1242

- Ross, Sarah Gwyneth (2010). The Birth of Feminism: woman as intellect in Renaissance Italy and England. Harvard University Press. p. 2.

- Antonietta Drago, Donne e amori del Risorgimento (Milano, Palazzi, 1960).

- "Professional Translation Services Agency — Kwintessential London". Archived from the original on 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on 2014-12-21. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- https://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/abortion/doc/italy.doc Archived 2016-03-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Torna l'aborto clandestino". Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- "Divorce Tourists Go Abroad to Quickly Dissolve Their Italian Marriages". The New York Times. 15 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "'Divorce Italian style' becomes easier, faster with new law". 23 April 2017. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017 – via Reuters.

- "Role of Traditions: Divorce in Italy — impowr.org". Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-02-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-11-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-11-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2017-02-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Eurostat - Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification". Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- OECD. "LFS by sex and age — indicators". Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- "Written question - Blank resignation letters - E-000233/2012". www.europarl.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "A Call for Aid, Not Laws, to Help Women in Italy". The New York Times. 19 August 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "BBC NEWS — Business — Why Italy's women are out of work". Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- Zampano, Giada (2 November 2013). "'Mancession' Pushes Italian Women Back Into Workforce" – via Wall Street Journal.

- "Labor force, female (% of total labor force) - Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "Sud Italia, questo non è un Paese per donne — E — il mensile online". Archived from the original on 2014-09-14. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- "BBC NEWS — Business — Why Italy's women are out of work". Archived from the original on 2008-04-13. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- "Festival del diritto". Festivaldeldiritto.it. Archived from the original on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- Corte Suprema di Cassazione (26 February 2004). "ATTI CONTRARI ALLA PUBBLICA DECENZA - ESPOSIZIONE DEL CORPO NUDO SULLA PUBBLICA SPIAGGIA - COSTITUISCE VIOLAZIONE ALL'ART. 726 C.P." www.giustizia.it (in Italian). Ministero della Giustizia. Archived from the original on 26 February 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

[...] diversamente da quella del seno nudo femminile, che ormai da vari lustri è comportamento comunemente accettato ed entrato nel costume sociale [...]

- Estatie, Lamia (20 March 2017). "Italian broadcaster cancels 'sexist' show". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Var tredje kvinna i Italien utsätts för våld: "Han tar ifrån dig allt, du vet inte längre vem du är och vad du vill"". svenska.yle.fi (in Swedish). Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- Povoledo, Elisabetta (2013-08-18). "A Call for Aid, Not Laws, to Help Women in Italy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- "Liste complète". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- "An overview of the legal and cultural issues for migrant Muslim women of the European union: A focus on domestic violence and Italy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- "Quality in Gender+ Equality Policies : European Commission Sixth Framework Programme Integrated Project" (PDF). Quing.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-07-16.

- "Sesso, matrimonio e legge". WOMAN's JOURNAL. 2011-12-08. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Van Cleave, Rachel A. “Rape and the Querela in Italy: False Protection of Victim Agency.” Michigan Journal of Gender & Law, vol. 13, 2007, pp. 273–310.

- Until 1981 the law read: Art. 587: He who causes the death of a spouse, daughter, or sister upon discovering her in illegitimate carnal relations and in the heat of passion caused by the offence to his honour or that of his family will be sentenced to three to seven years. The same sentence shall apply to whom, in the above circumstances, causes the death of the person involved in illegitimate carnal relations with his spouse, daughter, or sister. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Explainer: Why Is It So Hard To Stop 'Honor Killings'?". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "Revista de italianistica — Revista italia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

External links

- Valentina Piattelli, History of Women Emancipation in Italy

- Women in Italian universities

- Women in the Italian Resistance during WW2

- Italian women who made history

- Women in Italy, from the Unification to the present

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women of Italy. |