Lithuania

Lithuania (/ˌlɪθjuˈeɪniə/ (![]()

Republic of Lithuania | |

|---|---|

Location of Lithuania (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

.svg.png) Location of Lithuania in the World | |

| Capital and largest city | Vilnius 54°41′N 25°19′E |

| Official languages | Lithuanian |

Regional | Polish, Russian |

| Ethnic groups (census 2019[1]) |

|

| Religion (2016[2]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Lithuanian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[3][4][5][6] |

| Gitanas Nausėda | |

| Saulius Skvernelis | |

| Viktoras Pranckietis | |

| Legislature | Seimas |

| Independence | |

| 9 March 1009 | |

| 1236 | |

• Coronation of King Mindaugas | 6 July 1253 |

| 2 February 1386 | |

• Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth created | 1 July 1569 |

| 24 October 1795 | |

| 16 February 1918 | |

| 15 June 1940 | |

• Nazi German occupation | 22 June 1941 |

| July 1944 | |

| 11 March 1990 | |

| 17 September 1991 | |

| 29 March 2004 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total | 65,300 km2 (25,200 sq mi) (121st) |

• Water (%) | 1.35 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | |

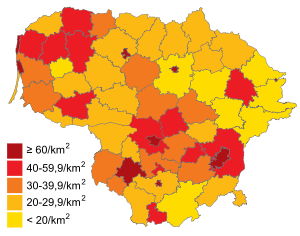

• Density | 43/km2 (111.4/sq mi) (173rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $107 billion[8] (83rd) |

• Per capita | $38,751[8] (38th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $56 billion[8] (80th) |

• Per capita | $20,355[8] (42nd) |

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 34th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Date format | yyyy-mm-dd (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +370 |

| ISO 3166 code | LT |

| Internet TLD | .lta |

Website www | |

| |

For centuries, the southeastern shores of the Baltic Sea were inhabited by various Baltic tribes. In the 1230s, the Lithuanian lands were united by Mindaugas and the Kingdom of Lithuania was created on 6 July 1253. During the 14th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the largest country in Europe;[13] present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland and Russia were the territories of the Grand Duchy. With the Lublin Union of 1569, Lithuania and Poland formed a voluntary two-state personal union, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth lasted more than two centuries, until neighbouring countries systematically dismantled it from 1772 to 1795, with the Russian Empire annexing most of Lithuania's territory.

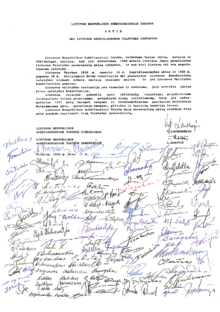

As World War I neared its end, Lithuania's Act of Independence was signed on 16 February 1918, declaring the founding of the modern Republic of Lithuania. In the midst of the Second World War, Lithuania was first occupied by the Soviet Union and then by Nazi Germany. As World War II neared its end and the Germans retreated, the Soviet Union reoccupied Lithuania. On 11 March 1990, a year before the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union, Lithuania became the first Baltic state[14] to declare itself independent, resulting in the restoration of an independent State of Lithuania.

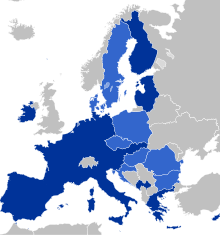

Lithuania is a developed country with an advanced, high-income economy,[15][16] a very high Human Development Index,[17] a very high standard of living and performs favourably in measurements of civil liberties, press freedom, internet freedom, democratic governance and peacefulness. Lithuania is a member of the European Union, the Council of Europe, eurozone, Schengen Agreement, NATO and OECD. It is also a member of the Nordic Investment Bank, part of Nordic-Baltic cooperation of Northern European countries, and is classified as a Northern European country by the United Nations.[18]

Etymology

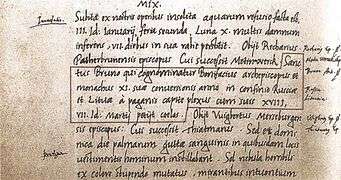

The first known record of the name of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuva) is in a 9 March 1009 story of Saint Bruno in the Quedlinburg Chronicle.[19] The Chronicle recorded a Latinized form of the name Lietuva: Litua[20] (pronounced [litua]). Due to the lack of reliable evidence, the true meaning of the name is unknown. Nowadays, scholars still debate the meaning of the word and there are a few plausible versions.

Since Lietuva has a suffix (-uva), the original word should have no suffix. A likely candidate is Lietā. Because many Baltic ethnonyms originated from hydronyms, linguists have searched for its origin among local hydronyms. Usually, such names evolved through the following process: hydronym → toponym → ethnonym.[21] Lietava, a small river not far from Kernavė, the core area of the early Lithuanian state and a possible first capital of the eventual Grand Duchy of Lithuania, is usually credited as the source of the name.[21] However, the river is very small and some find it improbable that such a small and local object could have lent its name to an entire nation. On the other hand, such naming is not unprecedented in world history.[22]

Artūras Dubonis proposed another hypothesis,[23] that Lietuva relates to the word leičiai (plural of leitis). From the middle of the 13th century, leičiai were a distinct warrior social group of the Lithuanian society subordinate to the Lithuanian ruler or the state itself. The word leičiai is used in the 14–16th century historical sources as an ethnonym for Lithuanians (but not Samogitians) and is still used, usually poetically or in historical contexts, in the Latvian language, which is closely related to Lithuanian.[24][25]

History

Prehistory

The first people settled in the territory of Lithuania after the last glacial period in the 10th millennium BC: Kunda, Neman and Narva cultures.[26] They were traveling hunters and did not form stable settlements. In the 8th millennium BC, the climate became much warmer, and forests developed. The inhabitants of what is now Lithuania then travelled less and engaged in local hunting, gathering and fresh-water fishing. Agriculture did not emerge until the 3rd millennium BC due to a harsh climate and terrain and a lack of suitable tools to cultivate the land. Crafts and trade also started to form at this time. Over a millennium, the Indo-Europeans, who arrived in the 3rd – 2nd millennium BC, mixed with the local population and formed various Baltic tribes.[27]

The Baltic tribes did not maintain close cultural or political contacts with the Roman Empire,[28] but they did maintain trade contacts (see Amber Road). Tacitus, in his study Germania, described the Aesti people, inhabitants of the south-eastern Baltic Sea shores who were probably Balts, around the year 97 AD. The Western Balts differentiated and became known to outside chroniclers first. Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD knew of the Galindians and Yotvingians, and early medieval chroniclers mentioned Old Prussians, Curonians and Semigallians.[29]

The Lithuanian language is considered to be very conservative for its close connection to Indo-European roots. It is believed to have differentiated from the Latvian language, the most closely related existing language, around the 7th century.[30] Traditional Lithuanian pagan customs and mythology, with many archaic elements, were long preserved. Rulers' bodies were cremated up until the conversion to Christianity: the descriptions of the cremation ceremonies of the grand dukes Algirdas and Kęstutis have survived.[31]

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, coastal Balts were subjected to raids by the Vikings,[33] and the kings of Denmark collected tribute at times. During the 10–11th centuries, Lithuanian territories were among the lands paying tribute to Kievan Rus', and Yaroslav the Wise was among the Ruthenian rulers who invaded Lithuania (from 1040). From the mid-12th century, it was the Lithuanians who were invading Ruthenian territories. In 1183, Polotsk and Pskov were ravaged, and even the distant and powerful Novgorod Republic was repeatedly threatened by the excursions from the emerging Lithuanian war machine toward the end of the 12th century.[34]

From the late 12th century, an organized Lithuanian military force existed; it was used for external raids, plundering and the gathering of slaves. Such military and pecuniary activities fostered social differentiation and triggered a struggle for power in Lithuania. This initiated the formation of early statehood, from which the Grand Duchy of Lithuania developed.[35]

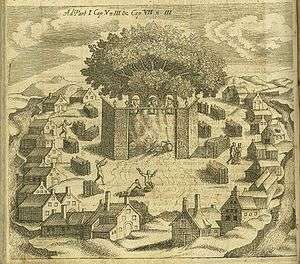

Initially inhabited by fragmented Baltic tribes, in the 1230s the Lithuanian lands were united by Mindaugas, who was crowned as King of Lithuania on 6 July 1253.[36] After his assassination in 1263, pagan Lithuania was a target of the Christian crusades of the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Order. Siege of Pilėnai is noted for the Lithuanians' defense against the intruders. Despite the devastating century-long struggle with the Orders, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania expanded rapidly, overtaking former Ruthenian principalities of Kievan Rus'.[37]

On 22 September 1236, the Battle of Saulė between Samogitians and the Livonian Brothers of the Sword took place close to Šiauliai. The Livonian Brothers were defeated during it and their further conquest of the Balts lands were stopped.[38] The battle inspired rebellions among the Curonians, Semigallians, Selonians, Oeselians, tribes previously conquered by the Sword-Brothers. Some thirty years' worth of conquests on the left bank of Daugava were lost.[39] In 2000, the Lithuanian and Latvian parliaments declared 22 September to be the Day of Baltic Unity.[40]

According to the legend, Grand Duke Gediminas was once hunting near the Vilnia River; tired after the successful hunt, he settled in for the night and dreamed of a huge Iron Wolf standing on top a hill and howling as strong and loud as a hundred wolves. Krivis (pagan priest) Lizdeika interpreted the dream that the Iron Wolf represents Vilnius Castles. Gediminas, obeying the will of gods, built the city and gave it the name Vilnius – from the stream of the Vilnia River.[41]

In 1362 or 1363, Grand Duke Algirdas achieved a decisive victory in the Battle of Blue Waters against Golden Horde and stopped its further expansion in the present-day Ukraine.[42] The victory brought the city of Kiev and a large part of present-day Ukraine, including sparsely populated Podolia and Dykra, under the control of the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[43] After taking Kiev, Lithuania became a direct neighbor and rival of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[44]

By the end of the 14th century, Lithuania was one of the largest countries in Europe and included present-day Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland and Russia.[45] The geopolitical situation between the west and the east determined the multicultural and multi-confessional character of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The ruling elite practised religious tolerance and Chancery Slavonic language was used as an auxiliary language to the Latin for official documents.[46]

In 1385, the Grand Duke Jogaila accepted Poland's offer to become its king. Jogaila embarked on gradual Christianization of Lithuania and established a personal union between Poland and Lithuania. Lithuania was one of the last pagan areas of Europe to adopt Christianity.

After two civil wars, Vytautas the Great became the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1392. During his reign, Lithuania reached the peak of its territorial expansion, centralization of the state began, and the Lithuanian nobility became increasingly prominent in state politics. In the great Battle of the Vorskla River in 1399, the combined forces of Tokhtamysh and Vytautas were defeated by the Mongols. Thanks to close cooperation, the armies of Lithuania and Poland achieved a victory over the Teutonic Knights in 1410 at the Battle of Grunwald, one of the largest battles of medieval Europe.[47][48][49]

In January 1429, at the Congress of Lutsk Vytautas received the title of King of Lithuania with the backing of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, but the envoys who were transporting the crown were stopped by Polish magnates in autumn of 1430. Another crown was sent, but Vytautas died in the Trakai Island Castle several days before it reached Lithuania. He was buried in the Cathedral of Vilnius.[50]

After the deaths of Jogaila and Vytautas, the Lithuanian nobility attempted to break the union between Poland and Lithuania, independently selecting Grand Dukes from the Jagiellon dynasty. But, at the end of the 15th century, Lithuania was forced to seek a closer alliance with Poland when the growing power of the Grand Duchy of Moscow threatened Lithuania's Russian principalities and sparked the Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars and the Livonian War.

%2C_Bitwa_pod_Orsz%C4%85.jpg)

On 8 September 1514, Battle of Orsha between Lithuanians, commanded by the Grand Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski, and Muscovites was fought. According to Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii by Sigismund von Herberstein, the primary source for information on the battle, the much smaller army of Poland–Lithuania (under 30,000 men) defeated a force of 80,000 Muscovite soldiers, capturing their camp and commander.[51] The battle destroyed a military alliance against Lithuania and Poland. Thousands of Muscovites were captured as prisoners and used as labourers in the Lithuanian manors, while Konstanty Ostrogski delivered the captured Muscovite flags to the Cathedral of Vilnius.[52][53]

The Livonian War was ceased for ten years with a Truce of Yam-Zapolsky signed on 15 January 1582 according to which the already Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth recovered Livonia, Polotsk and Velizh, but transferred Velikiye Luki to the Tsardom of Russia. The truce was extended for twenty years in 1600, when a diplomatic mission to Moscow led by Lew Sapieha concluded negotiations with Tsar Boris Godunov.[54] The truce was broken when the Poles invaded Muscovy in 1605.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

.jpg)

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was created in 1569 by the Union of Lublin. As a member of the Commonwealth, Lithuania retained its institutions, including a separate army, currency, and statutory laws – the Statute of Lithuania.[55] Eventually Polonization affected all aspects of Lithuanian life: politics, language, culture, and national identity. From the mid-16th to the mid-17th centuries, culture, arts, and education flourished, fueled by the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. From 1573, the Kings of Poland and Grand Dukes of Lithuania were elected by the nobility, who were granted ever increasing Golden Liberties. These liberties, especially the liberum veto, led to anarchy and the eventual dissolution of the state.

The Commonwealth reached its Golden Age in the early 17th century. Its powerful parliament was dominated by nobles who were reluctant to get involved in the Thirty Years' War; this neutrality spared the country from the ravages of a political-religious conflict that devastated most of contemporary Europe. The Commonwealth held its own against Sweden, the Tsardom of Russia, and vassals of the Ottoman Empire, and even launched successful expansionist offensives against its neighbours. In several invasions during the Time of Troubles, Commonwealth troops entered Russia and managed to take Moscow and hold it from 27 September 1610 to 4 November 1612, when they were driven out after a siege.[56]

In 1655, after the extinguishing battle, for the first time in history the Lithuanian capital Vilnius was taken by a foreign army.[57] The Russian army looted the city, splendid churches, and manors. Between 8,000 and 10,000 citizens were killed; the city burned for 17 days. Those who returned after the catastrophe could not recognise the city. The Russian occupation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania lasted up to 1661. Many artefacts and cultural heritage were either lost or looted, significant parts of the state archive – Lithuanian Metrica, collected since the 13th century, were lost and the rest was moved out of the country. During the Northern Wars (1655–1661), the Lithuanian territory and economy were devastated by the Swedish army. Almost all territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was occupied by Swedish and Russian armies. This period is known as Tvanas (The Deluge).

Before it could fully recover, Lithuania was ravaged during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). The war, a plague, and a famine caused the deaths of approximately 40% of the country's population.[58] Foreign powers, especially Russia, became dominant in the domestic politics of the Commonwealth. Numerous fractions among the nobility used the Golden Liberties to prevent any reforms.

The Constitution of 3 May 1791 was adopted by the Great Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth trying to save the state. The legislation was designed to redress the Commonwealth's political defects due to the system of Golden Liberties, also known as the "Nobles' Democracy," had conferred disproportionate rights on the nobility (szlachta) and over time had corrupted politics. The constitution sought to supplant the prevailing anarchy fostered by some of the country's magnates with a more democratic constitutional monarchy. It introduced elements of political equality between townspeople and nobility, and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thus mitigating the worst abuses of serfdom. It banned parliamentary institutions such as the liberum veto, which had put the Sejm at the mercy of any deputy who could revoke all the legislation that had been passed by that Sejm. It was drafted in relation to a copy of the United States Constitution.[59][60][61] Others have called it the world's second-oldest codified national governmental constitution after the 1787 U.S. Constitution.

Russian Empire

Eventually, the Commonwealth was partitioned in 1772, 1792, and 1795 by the Russian Empire, Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy.

The largest area of Lithuanian territory became part of the Russian Empire. After the unsuccessful uprisings in 1831 and 1863, the Tsarist authorities implemented a number of Russification policies. In 1840 the Third Statute of Lithuania was abolished. They banned the Lithuanian press, closed cultural and educational institutions and made Lithuania part of a new administrative region called Northwestern Krai. The Russification failed owing to an extensive network of Lithuanian book smugglers and secret Lithuanian home schooling.[62]

After the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), when German diplomats assigned what were seen as Russian spoils of war to Turkey, the relationship between Russia and the German Empire became complicated. The Russian Empire resumed the construction of fortresses at its western borders for defence against a potential invasion from Germany in the West. On 7 July 1879 the Russian Emperor Alexander II approved a proposal from the Russian military leadership to build the largest "first-class" defensive structure in the entire state – the 65 km2 (25 sq mi) Kaunas Fortress.[63] Large numbers of Lithuanians went to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine.[64]

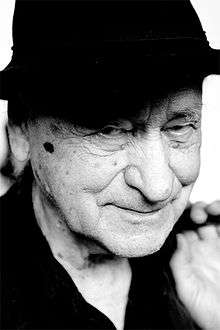

Simonas Daukantas promoted a return to Lithuania's pre-Commonwealth traditions, which he depicted as a Golden Age of Lithuania and a renewal of the native culture, based on the Lithuanian language and customs. With those ideas in mind, he wrote already in 1822 a history of Lithuania in Lithuanian – Darbai senųjų lietuvių ir žemaičių (The Deeds of Ancient Lithuanians and Samogitians), though it was not published at that time. A colleague of S. Daukantas, Teodor Narbutt wrote in Polish a voluminous Ancient History of the Lithuanian Nation (1835–1841), where he likewise expounded and expanded further on the concept of historic Lithuania, whose days of glory had ended with the Union of Lublin in 1569. Narbutt, invoking German scholarship, pointed out the relationship between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages. A Lithuanian National Revival, inspired by the ancient Lithuanian history, language and culture, laid the foundations of the modern Lithuanian nation and independent Lithuania.

20th and 21st centuries

1918–1939

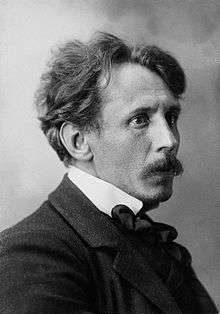

As a result of the Great Retreat during World War I, Germany occupied the entire territory of Lithuania and Courland by the end of 1915.[65] A new administrative entity, Ober Ost, was established. Lithuanians lost all political rights they had gained: personal freedom was restricted, and at the beginning, the Lithuanian press was banned.[66] However, the Lithuanian intelligentsia tried to take advantage of the existing geopolitical situation and began to look for opportunities to restore Lithuania's independence. On 18–22 September 1917, the Vilnius Conference elected the 20-member Council of Lithuania. The council adopted the Act of Independence of Lithuania on 16 February 1918 which proclaimed the restoration of the independent state of Lithuania governed by democratic principles, with Vilnius as its capital. The state of Lithuania which had been built within the framework of the Act lasted from 1918 until 1940.

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, the first Provisional Constitution of Lithuania was adopted and the first government of Prime Minister Augustinas Voldemaras was organized. At the same time, the army and other state institutions began to be organized. Lithuania fought three wars of independence: against the Bolsheviks who proclaimed the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, against the Bermontians, and against Poland.[67][68] As a result of the staged Żeligowski's Mutiny in October 1920, Poland took control of Vilnius Region and annexed it as Wilno Voivodeship in 1922.[69] Lithuania continued to claim Vilnius as its de jure capital and relations with Poland remained particularly tense and hostile for the entire interwar period. In January 1923, Lithuania staged the Klaipėda Revolt and captured Klaipėda Region (Memel territory) which was detached from East Prussia by the Treaty of Versailles. The region became an autonomous region of Lithuania.

On 15 May 1920, the first meeting of the democratically elected constituent assembly took place. The documents it adopted, i. e. the temporary (1920) and permanent (1922) constitutions of Lithuania, strove to regulate the life of the new state. Land, finance, and educational reforms started to be implemented. The currency of Lithuania, the Lithuanian litas, was introduced. The University of Lithuania was opened.[70] All major public institutions had been established. As Lithuania began to gain stability, foreign countries started to recognize it. In 1921 Lithuania was admitted to the League of Nations.[71]

On 17 December 1926, a military coup d'état took place, resulting in the replacement of the democratically elected government with a conservative authoritarian government led by Antanas Smetona. Augustinas Voldemaras was appointed to form a government. The so-called authoritarian phase had begun strengthening the influence of one party, the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, in the country. In 1927, the Seimas was dissolved.[72] A new constitution was adopted in 1928, which consolidated presidential powers. Gradually, opposition parties were banned, censorship was tightened, and the rights of national minorities were narrowed.[73][74]

On 15 July 1933, Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas, Lithuanian pilots, emigrants to the United States, made a significant flight in the history of world aviation. They flew across the Atlantic Ocean, covering a distance of 6,411 km (3,984 mi) without landing, in 37 hours and 11 minutes (172.4 km/h (107.1 mph)). In terms of comparison, as far as the distance of non-stop flights was concerned, their result ranked second only to that of Russell Boardman and John Polando.

The provisional capital Kaunas, which was nicknamed Little Paris, and the country itself had a Western standard of living with sufficiently high salaries and low prices. At the time, qualified workers there were earning very similar real wages as workers in Germany, Italy, Switzerland and France, the country also had a surprisingly high natural increase in population of 9.7 and the industrial production of Lithuania increased by 160% from 1913 to 1940.[75][76]

The situation was aggravated by the global economic crisis.[77] The purchase price of agricultural products had declined significantly. In 1935, farmers began strikes in Suvalkija and Dzūkija. In addition to economic ones, political demands were made. The government cruelly suppressed the unrest. In the spring of 1936, four peasants were sentenced to death for starting the riots.[78]

1939–1944

On 20 March 1939, after years of rising tensions, Lithuania was handed an ultimatum by Nazi Germany demanding it relinquish the Klaipėda Region. Two days later, the Lithuanian government accepted the ultimatum.[79] When Nazi Germany and Soviet Union concluded the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Lithuania was initially assigned to the German sphere of influence but was later transferred to the Soviet sphere. At the outbreak of World War II, Lithuania declared neutrality.[80]

In October 1939, Lithuania was forced to sign the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty: five Soviet military bases with 20,000 troops were established in Lithuania in exchange for Vilnius, which the Soviets had captured from Poland.[81] Delayed by the Winter War with Finland, the Soviets issued an ultimatum to Lithuania on 14 June 1940. They demanded the replacement of the Lithuanian government and that the Red Army be allowed into the country. The government decided that, with Soviet bases already in Lithuania, armed resistance was impossible and accepted the ultimatum.[82] President Smetona left the country, hoping to form a government in exile, while more than 200,000 Soviet Red Army soldiers crossed the Belarus–Lithuania border.[83] The next day, identical ultimatums were presented to Latvia and Estonia. The Baltic states were occupied. The Soviets followed semi-constitutional procedures for transforming the independent countries into soviet republics and incorporating them into the Soviet Union.

Vladimir Dekanozov was sent to supervise the formation of the puppet People's Government and the rigged election to the People's Seimas. The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on 21 July and accepted into the Soviet Union on 3 August. Lithuania was rapidly Sovietized: political parties and various organizations (except the Communist Party of Lithuania) were outlawed, some 12,000 people, including many prominent figures, were arrested and imprisoned in Gulag as "enemies of the people", larger private property was nationalized, the Lithuanian litas was replaced by the Soviet ruble, farm taxes were increased by 50–200%, the Lithuanian Army was transformed into the 29th Rifle Corps of the Red Army.[84] On 14–18 June 1941, less than a week before the Nazi invasion, some 17,000 Lithuanians were deported to Siberia, where many perished due to inhumane living conditions (see the June deportation).[85][86] The occupation was not recognized by Western powers and the Lithuanian Diplomatic Service, based on pre-war consulates and legations, continued to represent independent Lithuania until 1990.

When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Lithuanians began the anti-Soviet June Uprising, organized by the Lithuanian Activist Front. Lithuanians proclaimed independence and organized the Provisional Government of Lithuania. This government quickly self-disbanded.[87] Lithuania became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland, German civil administration.[88]

By 1 December 1941, over 120,000 Lithuanian Jews, or 91–95% of Lithuania's pre-war Jewish community, had been killed.[89]:110 Nearly 100,000 Jews, Poles, Russians and Lithuanians were murdered at Paneriai.[90] However, thousands of Lithuanian families risking their lives also protected Jews from the Holocaust.[91] Israel has recognized 893 Lithuanians (as of 1 January 2018) as Righteous Among the Nations for risking their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust.[92]

Approximately 13,000 men served in the Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions.[93] 10 of the 26 Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions working with the Nazi Einsatzkommando, were involved in the mass killings. Rogue units organised by Algirdas Klimaitis and supervised by SS Brigadeführer Walter Stahlecker started the Kaunas pogrom in and around Kaunas on 25 June 1941.[94][95] In 1941, the Lithuanian Security Police (Lietuvos saugumo policija), subordinate to Nazi Germany's Security Police and Nazi Germany's Criminal Police, was created. The Lietuvos saugumo policija targeted the communist underground.[96]

A new occupation had begun. Nationalized assets were not returned to the residents. Some of them were forced to fight for Nazi Germany or were taken to German territories as forced labourers. Jewish people were herded into ghettos and gradually killed by shooting or sending them out to concentration camps.[97][98]

1944–1990

After the retreat of the German armed forces, the Soviets reestablished their control of Lithuania in July–October 1944. The massive deportations to Siberia were resumed and lasted until the death of Stalin in 1953. Antanas Sniečkus, the leader of the Communist Party of Lithuania from 1940 to 1974,[99] supervised the arrests and deportations.[100] All Lithuanian national symbols were banned. Under the pretext of Lithuania's economic recovery, the Moscow authorities encouraged the migration of workers and other specialists to Lithuania with the intention to further integrate Lithuania into the Soviet Union and to develop the country's industry. At the same time, Lithuanians were lured to work in the USSR by promising them all the privileges of settling in a new place.

The second Soviet occupation was accompanied by the guerrilla warfare of the Lithuanian population, which took place in 1944–1953. It sought to restore an independent state of Lithuania, to consolidate democracy by destroying communism in the country, returning national values and the freedom of religion. About 50,000 Lithuanians took to the forests and fought Soviet occupants with a gun in their hands.[101][102] In the later stages of the partisan war, Lithuanians formed the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters and its leader Jonas Žemaitis (codename Vytautas) was posthumously recognized as the president of Lithuania.[103] Despite the fact that the guerrilla warfare did not achieve its goal of liberating Lithuania and that it resulted in more than 20,000 deaths, the armed resistance de facto demonstrated that Lithuania did not voluntarily join the USSR and it also legitimized the will of the people of Lithuania to be independent.[104] Lithuanian courts and the ECHR both treat the Soviets' annihilation of the Lithuanian partisans as a genocide.[105]

Even with the suppression of partisan resistance, the Soviet government failed to stop the movement for the independence of Lithuania. The underground dissident groups were active publishing the underground press and Catholic literature. The most active participants of the movement included Vincentas Sladkevičius, Sigitas Tamkevičius and Nijolė Sadūnaitė. In 1972, after Romas Kalanta's public self-immolation, the unrest in Kaunas lasted for several days.[106]

.jpg)

The Helsinki Group, which was founded in Lithuania after the international conference in Helsinki (Finland), where the post-WWII borders were acknowledged, announced a declaration for Lithuania's independence on foreign radio station.[107] The Helsinki Group informed the Western world about the situation in the Soviet Lithuania and violations of human rights. With the beginning of the increased openness and transparency in government institutions and activities (glasnost) in the Soviet Union, on 3 June 1988, the Sąjūdis was established in Lithuania. Very soon it began to seek country's independence.[108] Vytautas Landsbergis became movement's leader.[109] The supporters of Sąjūdis joined movement's groups all over Lithuania. On 23 August 1988 a big rally took place at the Vingis Park in Vilnius. It was attended by approx. 250,000 people.[110] A year later, on 23 August 1989 commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and aiming to draw the attention of the whole world to the occupation of the Baltic states, a political demonstration, the Baltic Way, was organized.[111] The event, led by Sąjūdis, was a human chain spanning about 600 kilometres (370 mi) across the three Baltic capitals—Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn. The peaceful demonstration showed the desire of the people of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to break away from the USSR.

1990–present

On 11 March 1990, the Supreme Council announced the restoration of Lithuania's independence. Lithuania became the first Soviet occupied state to announce restitution of independence. On 20 April 1990, the Soviets imposed an economic blockade by ceasing to deliver supplies of raw materials (primarily oil) to Lithuania.[113] Not only the domestic industry, but also the population started feeling the lack of fuel, essential goods, and even hot water. Although the blockade lasted for 74 days, Lithuania did not renounce the declaration of independence.

Gradually, economic relations had been restored. However, tensions had peaked again in January 1991. At that time, attempts were made to carry out a coup using the Soviet Armed Forces, the Internal Army of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the USSR Committee for State Security (KGB). Because of the poor economic situation in Lithuania, the forces in Moscow thought the coup d'état would receive strong public support.[114]

People from all over Lithuania flooded to Vilnius to defend their legitimately elected Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania and independence. The coup ended with a few casualties of peaceful civilians and caused huge material loss. Not a single person who defended Lithuanian Parliament or other state institutions used a weapon, but the Soviet Army did. Soviet soldiers killed 14 people and injured hundreds. A large part of the Lithuanian population participated in the January Events.[116][117] Shortly after, on 11 February 1991, the Icelandic parliament voted to confirm that Iceland's 1922 recognition of Lithuanian independence was still in full effect, as it never formally recognized the Soviet Union's control over Lithuania,[118] and that full diplomatic relations should be established as soon as possible.[119][120]

On 31 July 1991, Soviet paramilitaries killed seven Lithuanian border guards on the Belarusian border in what became known as the Medininkai Massacre.[121] On 17 September 1991, Lithuania was admitted to the United Nations.

On 25 October 1992 the citizens of Lithuania voted in a referendum to adopt the current constitution. On 14 February 1993, during the direct general elections, Algirdas Brazauskas became the first president after the restoration of independence of Lithuania. On 31 August 1993 the last units of the Soviet Army left the territory of Lithuania.[122] Since 29 March 2004, Lithuania has been part of the NATO. On 1 May 2004, it became a fully-fledged member of the European Union, and a member of the Schengen Agreement on 21 December 2007.

Geography

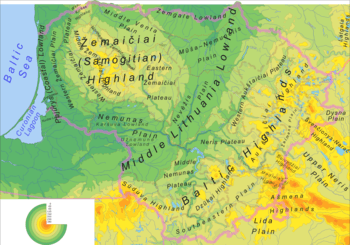

Lithuania is located in the Baltic region of EuropeNote and covers an area of 65,200 km2 (25,200 sq mi).[123] It lies between latitudes 53° and 57° N, and mostly between longitudes 21° and 27° E (part of the Curonian Spit lies west of 21°). It has around 99 kilometres (61.5 mi) of sandy coastline, only about 38 kilometres (24 mi) of which face the open Baltic Sea, less than the other two Baltic Sea countries. The rest of the coast is sheltered by the Curonian sand peninsula. Lithuania's major warm-water port, Klaipėda, lies at the narrow mouth of the Curonian Lagoon (Lithuanian: Kuršių marios), a shallow lagoon extending south to Kaliningrad. The country's main and largest river, the Nemunas River, and some of its tributaries carry international shipping.

Lithuania lies at the edge of the North European Plain. Its landscape was smoothed by the glaciers of the last ice age, and is a combination of moderate lowlands and highlands. Its highest point is Aukštojas Hill at 294 metres (965 ft) in the eastern part of the country. The terrain features numerous lakes (Lake Vištytis, for example) and wetlands, and a mixed forest zone covers over 33% of the country. Drūkšiai is the largest, Tauragnas is the deepest and Asveja is the longest lake in Lithuania.

After a re-estimation of the boundaries of the continent of Europe in 1989, Jean-George Affholder, a scientist at the Institut Géographique National (French National Geographic Institute), determined that the geographic centre of Europe was in Lithuania, at 54°54′N 25°19′E, 26 kilometres (16 mi) north of Lithuania's capital city of Vilnius.[124] Affholder accomplished this by calculating the centre of gravity of the geometrical figure of Europe.

Climate

Lithuania has a temperate climate with both maritime and continental influences. It is defined as humid continental (Dfb) under the Köppen climate classification (but is close to oceanic in a narrow coastal zone).

Average temperatures on the coast are −2.5 °C (27.5 °F) in January and 16 °C (61 °F) in July. In Vilnius the average temperatures are −6 °C (21 °F) in January and 17 °C (63 °F) in July. During the summer, 20 °C (68 °F) is common during the day while 14 °C (57 °F) is common at night; in the past, temperatures have reached as high as 30 or 35 °C (86 or 95 °F). Some winters can be very cold. −20 °C (−4 °F) occurs almost every winter. Winter extremes are −34 °C (−29 °F) in coastal areas and −43 °C (−45 °F) in the east of Lithuania.

The average annual precipitation is 800 mm (31.5 in) on the coast, 900 mm (35.4 in) in the Samogitia highlands and 600 mm (23.6 in) in the eastern part of the country. Snow occurs every year, it can snow from October to April. In some years sleet can fall in September or May. The growing season lasts 202 days in the western part of the country and 169 days in the eastern part. Severe storms are rare in the eastern part of Lithuania but common in the coastal areas.

The longest records of measured temperature in the Baltic area cover about 250 years. The data show warm periods during the latter half of the 18th century, and that the 19th century was a relatively cool period. An early 20th century warming culminated in the 1930s, followed by a smaller cooling that lasted until the 1960s. A warming trend has persisted since then.[125]

Lithuania experienced a drought in 2002, causing forest and peat bog fires.[126] The country suffered along with the rest of Northwestern Europe during a heat wave in the summer of 2006.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

35.1 (95.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −40.5 (−40.9) |

−42.9 (−45.2) |

−37.5 (−35.5) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−34.0 (−29.2) |

−42.9 (−45.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.2 (1.43) |

30.1 (1.19) |

33.9 (1.33) |

42.9 (1.69) |

52.0 (2.05) |

69.0 (2.72) |

76.9 (3.03) |

77.0 (3.03) |

60.3 (2.37) |

49.9 (1.96) |

50.4 (1.98) |

47.0 (1.85) |

625.5 (24.63) |

| Source 1: Records of Lithuanian climate[127][128] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase[129] | |||||||||||||

Environment

.jpg)

After the restoration of Lithuania's independence in 1990, the Aplinkos apsaugos įstatymas (Environmental Protection Act) was adopted already in 1992. The law provided the foundations for regulating social relations in the field of environmental protection, established the basic rights and obligations of legal and natural persons in preserving the biodiversity inherent in Lithuania, ecological systems and the landscape.[131] Lithuania agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 20% of 1990 levels by the year 2020 and by at least 40% by the year 2030, together with all European Union members. Also, by 2020 at least 20% (27% by 2030) of country's total energy consumption should be from the renewable energy sources.[132] In 2016, Lithuania introduced especially effective container deposit legislation, which resulted in collecting 92% of all packagings in 2017.[133]

Lithuania does not have high mountains and its landscape is dominated by blooming meadows, dense forests and fertile fields of cereals. However it stands out by the abundance of hillforts, which previously had castles where the ancient Lithuanians burned altars for pagan gods.[134] Lithuania is a particularly watered region with more than 3,000 lakes, mostly in the northeast. The country is also drained by numerous rivers, most notably the longest Nemunas.[134]

Forest has long been one of the most important natural resources in Lithuania. Forests occupy one third of the country's territory and timber-related industrial production accounts for almost 11% industrial production in the country.[135] Lithuania has five national parks,[136] 30 regional parks,[137] 402 nature reserves,[138] 668 state-protected natural heritage objects.[139]

Lithuania is ranked fifth, second to Sweden (first 3 places are not granted) in Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI).[140]

Biodiversity

Lithuanian ecosystems include natural and semi-natural (forests, bogs, wetlands and meadows), and anthropogenic (agrarian and urban) ecosystems. Among natural ecosystems, forests are particularly important to Lithuania, covering 33% of the country's territory. Wetlands (raised bogs, fens, transitional mires, etc.) cover 7.9% of the country, with 70% of wetlands having been lost due to drainage and peat extraction between 1960 and 1980. Changes in wetland plant communities resulted in the replacement of moss and grass communities by trees and shrubs, and fens not directly affected by land reclamation have become drier as a result of a drop in the water table. There are 29,000 rivers with a total length of 64,000 km in Lithuania, the Nemunas River basin occupying 74% of the territory of the country. Due to the construction of dams, approximately 70% of spawning sites of potential catadromous fish species have disappeared. In some cases, river and lake ecosystems continue to be impacted by anthropogenic eutrophication.[143]

Agricultural land comprises 54% of Lithuania's territory (roughly 70% of that is arable land and 30% meadows and pastures), approximately 400,000 ha of agricultural land is not farmed, and acts as an ecological niche for weeds and invasive plant species. Habitat deterioration is occurring in regions with very productive and expensive lands as crop areas are expanded. Currently, 18.9% of all plant species, including 1.87% of all known fungi species and 31% of all known species of lichens, are listed in the Lithuanian Red Data Book. The list also contains 8% of all fish species.[143]

The wildlife populations have rebounded as the hunting became more restricted and urbanization allowed replanting forests (forests already tripled in size since their lows). Currently, Lithuania has approximately 250,000 larger wild animals or 5 per each square kilometer. The most prolific large wild animal in every part of Lithuania is the roe deer, with 120,000 of them. They are followed by boars (55,000). Other ungulates are the deer (~22,000), fallow-deer (~21,000) and the largest one: moose (~7,000). Among the Lithuanian predators, foxes are the most common (~27,000). Wolves are, however, more ingrained into the mythology as there are just 800 in Lithuania. Even rarer are the lynxes (~200). The large animals mentioned above exclude the rabbit, ~200,000 of which may live in the Lithuanian forests.[144]

Politics

Government

Since Lithuania declared the restoration of its independence on 11 March 1990, it has maintained strong democratic traditions. It held its first independent general elections on 25 October 1992, in which 56.75% of voters supported the new constitution.[145] There were intense debates concerning the constitution, particularly the role of the president. A separate referendum was held on 23 May 1992 to gauge public opinion on the matter, and 41% of voters supported the restoration of the President of Lithuania.[145] Through compromise, a semi-presidential system was agreed on.[3]

President since 2019

The Lithuanian head of state is the president, directly elected for a five-year term and serving a maximum of two terms. The president oversees foreign affairs and national security, and is the commander-in-chief of the military.[146] The president also appoints the prime minister and, on the latter's nomination, the rest of the cabinet, as well as a number of other top civil servants and the judges for all courts.[146] The current Lithuanian head of state, Gitanas Nausėda was elected on 26 May 2019 by unanimously winning in all municipalities of Lithuania.[147]

The judges of the Constitutional Court (Konstitucinis Teismas) serve nine-year terms. They are appointed by the President, the Chairman of the Seimas, and the Chairman of the Supreme Court, each of whom appoint three judges. The unicameral Lithuanian parliament, the Seimas, has 141 members who are elected to four-year terms. 71 of the members of its members are elected in single-member constituencies, and the others in a nationwide vote by proportional representation. A party must receive at least 5% of the national vote to be eligible for any of the 70 national seats in the Seimas.[148]

Political parties and elections

Lithuania was one of the first countries in the world to grant women a right to vote in the elections. Lithuanian women were allowed to vote by the 1918 Constitution of Lithuania and used their newly granted right for the first time in 1919. By doing so, Lithuania allowed it earlier than such democratic countries as the United States (1920), France (1945), Greece (1952), Switzerland (1971).[149]

Lithuania exhibits a fragmented multi-party system,[150] with a number of small parties in which coalition governments are common. Ordinary elections to the Seimas take place on the second Sunday of October every four years.[148] To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 25 years old on the election day, not under allegiance to a foreign state and permanently reside in Lithuania. Persons serving or due to serve a sentence imposed by the court 65 days before the election are not eligible. Also, judges, citizens performing military service, and servicemen of professional military service and officials of statutory institutions and establishments may not stand for election.[151] Lithuanian Peasant and Greens Union won the 2016 Lithuanian parliamentary elections and gained 54 of 141 seats in the parliament.[152]

.jpg)

The President of Lithuania is the head of state of the country, elected to a five-year term in a majority vote. Elections take place on the last Sunday no more than two months before the end of current presidential term.[153] To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 40 years old on the election day and reside in Lithuania for at least three years, in addition to satisfying the eligibility criteria for a member of the parliament. Same President may serve for not more than two terms.[154] Gitanas Nausėda has won the most recent election as an independent candidate in 2019.[147]

Each municipality in Lithuania is governed by a municipal council and a mayor, who is a member of the municipal council. The number of members, elected on a four-year term, in each municipal council depends on the size of the municipality and varies from 15 (in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 residents) to 51 (in municipalities with more than 500,000 residents). 1,524 municipal council members were elected in 2015.[155] Members of the council, with the exception of the mayor, are elected using proportional representation. Starting with 2015, the mayor is elected directly by the majority of residents of the municipality.[156] Social Democratic Party of Lithuania won most of the positions in the 2015 elections (372 municipal councils seats and 16 mayors).[157]

As of 2019, the number of seats in the European Parliament allocated to Lithuania was 11.[158] Ordinary elections take place on a Sunday on the same day as in other EU countries. The vote is open to all citizens of Lithuania, as well as citizens of other EU countries that permanently reside in Lithuania, who are at least 18 years old on the election day. To be eligible for election, candidates must be at least 21 years old on the election day, citizen of Lithuania or citizen of another EU country permanently residing in Lithuania. Candidates are not allowed to stand for election in more than one country. Persons serving or due to serve a sentence imposed by the court 65 days before the election are not eligible. Also, judges, citizens performing military service, and servicemen of professional military service and officials of statutory institutions and establishments may not stand for election.[159] Six political parties and one committee representatives gained seats in the 2019 elections.[160]

Law and law enforcement

.jpg)

After regaining of independence in 1990, the largely modified Soviet legal codes were in force for about a decade. The current Constitution of Lithuania was adopted on 25 October 1992.[161] In 2001, the Civil Code of Lithuania was passed in Seimas. It was succeeded by the Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code in 2003. The approach to the criminal law is inquisitorial, as opposed to adversarial; it is generally characterised by an insistence on formality and rationalisation, as opposed to practicality and informality. Normative legal act enters into force on the next day after its publication in the Teisės aktų registras, unless it has a later entry into force date.[162]

The European Union law is an integral part of the Lithuanian legal system since 1 May 2004.[163]

Lithuania, after breaking away from the Soviet Union had a difficult crime situation, however the Lithuanian law enforcement agencies eliminated many criminals over the years, making Lithuania a reasonably safe country.[164] Crime in Lithuania has been declining rapidly.[165] Law enforcement in Lithuania is primarily the responsibility of local Lietuvos policija (Lithuanian Police) commissariats. They are supplemented by the Lietuvos policijos antiteroristinių operacijų rinktinė Aras (Anti-Terrorist Operations Team of the Lithuanian Police Aras), Lietuvos kriminalinės policijos biuras (Lithuanian Criminal Police Bureau), Lietuvos policijos kriminalistinių tyrimų centras (Lithuanian Police Forensic Research Center) and Lietuvos kelių policijos tarnyba (Lithuanian Road Police Service).[166]

In 2017, there were 63,846 crimes registered in Lithuania. Of these, thefts comprised a large part with 19,630 cases (13.2% less than in 2016). While 2,835 crimes were very hard and hard (crimes that may result in more than six years imprisonment), which is 14.5% less than in 2016. Totally, 129 homicides or attempted homicide occurred (19.9% less than in 2016), while serious bodily harm was registered 178 times (17.6% less than in 2016). Another problematic crime contraband cases also decreased by 27.2% from 2016 numbers. Meanwhile, crimes in electronic data and information technology security fields noticeably increased by 26.6%.[167] In the 2013 Special Eurobarometer, 29% of Lithuanians said that corruption affects their daily lives (EU average 26%). Moreover, 95% of Lithuanians regarded corruption as widespread in their country (EU average 76%), and 88% agreed that bribery and the use of connections is often the easiest way of obtaining certain public services (EU average 73%).[168] Though, according to local branch of Transparency International, corruption levels have been decreasing over the past decade.[169]

Capital punishment in Lithuania was suspended in 1996 and fully eliminated in 1998.[170] Lithuania has the highest number of prison inmates in the EU. According to scientist Gintautas Sakalauskas, this is not because of a high criminality rate in the country, but due to Lithuania's high repression level and the lack of trust of the convicted, who are frequently sentenced to a jail imprisonment.[171]

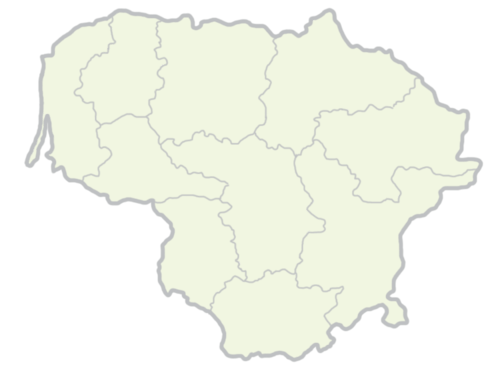

Administrative divisions

The current system of administrative division was established in 1994 and modified in 2000 to meet the requirements of the European Union. The country's 10 counties (Lithuanian: singular – apskritis, plural – apskritys) are subdivided into 60 municipalities (Lithuanian: singular – savivaldybė, plural – savivaldybės), and further divided into 500 elderships (Lithuanian: singular – seniūnija, plural – seniūnijos).

Municipalities have been the most important unit of administration in Lithuania since the system of county governorship (apskrities viršininkas) was dissolved in 2010.[172] Some municipalities are historically called "district municipalities" (often shortened to "district"), while others are called "city municipalities" (sometimes shortened to "city"). Each has its own elected government. The election of municipality councils originally occurred every three years, but now takes place every four years. The council appoints elders to govern the elderships. Mayors have been directly elected since 2015; prior to that, they were appointed by the council.[173]

Elderships, numbering over 500, are the smallest administrative units and do not play a role in national politics. They provide necessary local public services—for example, registering births and deaths in rural areas. They are most active in the social sector, identifying needy individuals or families and organizing and distributing welfare and other forms of relief.[174] Some citizens feel that elderships have no real power and receive too little attention, and that they could otherwise become a source of local initiative for addressing rural problems.[175]

| County | Area (km²) | Population (thousands) in 2018[176] | Nominal GDP billions EUR in 2018[176] | Nominal GDP per capita EUR in 2018[176] | GDP PPP per capita USD in 2018[176][177] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle and Western Lithuania | 55,569 | 1,992 | 26.4 | 13,300 | 28,600 |

| Alytus County | 5,425 | 137 | 1.3 | 9,800 | 21,100 |

| Kaunas County | 8,089 | 562 | 9.4 | 15,200 | 32,700 |

| Klaipėda County | 5,209 | 318 | 4.9 | 15,600 | 33,500 |

| Marijampolė County | 4,463 | 140 | 1.3 | 9,400 | 20,200 |

| Panevėžys County | 7,881 | 222 | 2.6 | 11,800 | 25,400 |

| Šiauliai County | 8,540 | 264 | 3.2 | 12,200 | 26,200 |

| Tauragė County | 4,411 | 95 | 0.9 | 9,100 | 19,600 |

| Telšiai County | 4,350 | 136 | 1.5 | 11,600 | 24,900 |

| Utena County | 7,201 | 128 | 1.2 | 9,300 | 20,000 |

| Capital region of Lithuania (Vilnius county) |

9,731 | 808 | 18.9 | 23,400 | 50,300 |

| Lithuania | 65,300 | 2,800 | 45.3 | 16,200 | 34,800 |

Foreign relations

Lithuania became a member of the United Nations on 18 September 1991, and is a signatory to a number of its organizations and other international agreements. It is also a member of the European Union, the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, as well as NATO and its adjunct North Atlantic Coordinating Council. Lithuania gained membership in the World Trade Organization on 31 May 2001, and joined the OECD on 5 July 2018,[178] while also seeking membership in other Western organizations.

Lithuania has established diplomatic relations with 149 countries.[179]

In 2011, Lithuania hosted the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Ministerial Council Meeting. During the second half of 2013, Lithuania assumed the role of the presidency of the European Union.

Lithuania is also active in developing cooperation among northern European countries. It has been a member of the Baltic Council since its establishment in 1993. The Baltic Council, located in Tallinn, is a permanent organisation of international cooperation that operates through the Baltic Assembly and the Baltic Council of Ministers.

Lithuania also cooperates with Nordic and the two other Baltic countries through the NB8 format. A similar format, NB6, unites Nordic and Baltic members of EU. NB6's focus is to discuss and agree on positions before presenting them to the Council of the European Union and at the meetings of EU foreign affairs ministers.

The Council of the Baltic Sea States (CBSS) was established in Copenhagen in 1992 as an informal regional political forum. Its main aim is to promote integration and to close contacts between the region's countries. The members of CBSS are Iceland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Russia, and the European Commission. Its observer states are Belarus, France, Italy, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine.

The Nordic Council of Ministers and Lithuania engage in political cooperation to attain mutual goals and to determine new trends and possibilities for joint cooperation. The Council's information office aims to disseminate Nordic concepts and to demonstrate and promote Nordic cooperation.

.jpg)

Lithuania, together with the five Nordic countries and the two other Baltic countries, is a member of the Nordic Investment Bank (NIB) and cooperates in its NORDPLUS programme, which is committed to education.

The Baltic Development Forum (BDF) is an independent nonprofit organization that unites large companies, cities, business associations and institutions in the Baltic Sea region. In 2010 the BDF's 12th summit was held in Vilnius.[180]

Poland was highly supportive of Lithuanian independence, despite Lithuania's discriminatory treatment of its Polish minority.[181][182] The former Solidarity leader and Polish President Lech Wałęsa criticised the government of Lithuania over discrimination against the Polish minority and rejected Lithuania's Order of Vytautas the Great.[183] Lithuania maintains greatly warm mutual relations with Georgia and strongly supports its European Union and NATO aspirations.[184][185][186] During the Russo-Georgian War in 2008, when the Russian troops were occupying the territory of Georgia and approaching towards the Georgian capital Tbilisi, President Valdas Adamkus, together with the Polish and Ukrainian presidents, went to Tbilisi by answering to the Georgians request of the international assistance.[187][188] Shortly, Lithuanians and the Lithuanian Catholic Church also began collecting financial support for the war victims.[189][190]

In 2004–2009, Dalia Grybauskaitė served as European Commissioner for Financial Programming and the Budget within the José Manuel Barroso-led Commission.

In 2013, Lithuania was elected to the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term,[191] becoming the first Baltic country elected to this post. During its membership, Lithuania actively supported Ukraine and often condemned Russia for the military intervention in Ukraine, immediately earning vast Ukrainians esteem.[192][193] As the War in Donbass progressed, President Dalia Grybauskaitė has compared the Russian President Vladimir Putin to Josef Stalin and to Adolf Hitler, she has also called Russia a "terrorist state".[194] In 2018 Lithuania, along with Latvia and Estonia were awarded the Peace of Westphalia Prize – for their exceptional model of democratic development and contribution to peace in the continent.[195] In 2019 Lithuania condemned the Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria.[196]

Military

The Lithuanian Armed Forces is the name for the unified armed forces of Lithuanian Land Force, Lithuanian Air Force, Lithuanian Naval Force, Lithuanian Special Operations Force and other units: Logistics Command, Training and Doctrine Command, Headquarters Battalion, Military Police. Directly subordinated to the Chief of Defence are the Special Operations Forces and Military Police. The Reserve Forces are under command of the Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces.

The Lithuanian Armed Forces consist of some 17,000 active personnel, which may be supported by reserve forces.[197] Compulsory conscription ended in 2008 but was reintroduced in 2015.[198] The Lithuanian Armed Forces currently have deployed personnel on international missions in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Mali and Somalia.[199]

In March 2004, Lithuania became a full member of the NATO. Since then, fighter jets of NATO members are deployed in Zokniai airport and provide safety for the Baltic airspace.

Since the summer of 2005 Lithuania has been part of the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan (ISAF), leading a Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in the town of Chaghcharan in the province of Ghor. The PRT includes personnel from Denmark, Iceland and USA. There are also special operation forces units in Afghanistan, placed in Kandahar Province. Since joining international operations in 1994, Lithuania has lost two soldiers: Lt. Normundas Valteris fell in Bosnia, as his patrol vehicle drove over a mine. Sgt. Arūnas Jarmalavičius was fatally wounded during an attack on the camp of his Provincial Reconstruction Team in Afghanistan.[200]

The Lithuanian National Defence Policy aims to guarantee the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of the state, the integrity of its land, territorial waters and airspace, and its constitutional order. Its main strategic goals are to defend the country's interests, and to maintain and expand the capabilities of its armed forces so they may contribute to and participate in the missions of NATO and European Union member states.[201]

The defense ministry is responsible for combat forces, search and rescue, and intelligence operations. The 5,000 border guards fall under the Interior Ministry's supervision and are responsible for border protection, passport and customs duties, and share responsibility with the navy for smuggling and drug trafficking interdiction. A special security department handles VIP protection and communications security. In 2015 National Cyber Security Centre of Lithuania was created. Paramilitary organisation Lithuanian Riflemen's Union acts as civilian self-defence institution.

According to NATO, in 2017 Lithuania allocated 1.77% of its GDP to the national defense. For a long time Lithuania lagged behind NATO allies in terms of defense spending, but in recent years it has begun to rapidly increase the funding. In 2018 Lithuania intends to allocate 2.06% of its GDP to the defense sector and reach the required funding standard for NATO.[202]

Economy

Lithuania has open and mixed economy that is classified as high-income economy by the World Bank.[203] According to data from 2016, the three largest sectors in Lithuanian economy are – services (68.3% of GDP), industry (28.5%) and agriculture (3.3%).[204] World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report ranks Lithuania 41st (of 137 ranked countries).

Lithuania joined NATO in 2004,[205] EU in 2004,[206] Schengen in 2007[207] and OECD in 2018.[178]

On 1 January 2015, euro became the national currency replacing litas at the rate of EUR 1.00 = LTL 3.45280.[208]

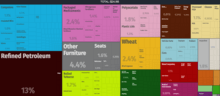

Agricultural products and food made 18.3%, chemical products and plastics – 17.8%, machinery and appliances – 15.8%, mineral products – 14.7%, wood and furniture – 12.5% of exports.[209] According to data from 2016, more than half of all Lithuanian exports go to 7 countries including Russia (14%), Latvia (9,9%), Poland (9,1%), Germany (7,7%), Estonia (5,3%), Sweden (4,8%) and United Kingdom (4,3%).[210] Exports equaled 81.31 percent of Lithuania's GDP in 2017.[211]

Lithuanian GDP experienced very high real growth rates for decade up to 2009, peaking at 11.1% in 2007. As a result, the country was often termed as a Baltic Tiger. However, in 2009 due to a global financial crisis marked experienced a drastic decline – GDP contracted by 14.9%[212] and unemployment rate reached 17.8% in 2010.[213] After the decline of 2009, Lithuanian annual economic growth has been much slower compared to pre-2009 years. According to IMF, financial conditions are conducive to growth and financial soundness indicators remain strong. The public debt ratio in 2016 fell to 40 percent of GDP, to compare with 42.7 in 2015 (before global finance crisis – 15 percent of GDP in 2008).[214]

On average, more than 95% of all foreign direct investment in Lithuania comes from European Union countries. Sweden is historically the largest investor with 20% – 30% of all FDI in Lithuania.[216] FDI into Lithuania spiked in 2017, reaching its highest ever recorded number of greenfield investment projects. In 2017, Lithuania was third country, after Ireland and Singapore by the average job value of investment projects.[217] The US was the leading source country in 2017, 24.59% of total FDI. Next up are Germany and the UK, each representing 11.48% of total project numbers.[218] Based on the Eurostat's data, in 2017, the value of Lithuanian exports recorded the most rapid growth not only in the Baltic countries, but also across Europe, which was 16.9 per cent.[219]

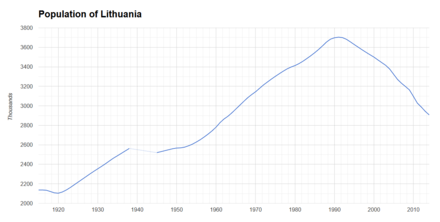

In the period between 2004 and 2016, one out of five Lithuanians left the country, mostly because of insufficient income situation[220] or seeking the new experience and studies abroad. Long term emigration and economy growth has resulted in noticeable shortages on the labour market[221] and growth in salaries being larger than growth in labour efficiency.[222] Unemployment rate in 2017 was 8.1%.[223]

As of 2019, Lithuanian mean wealth per adult is $50,254, while total national wealth is $115 billion.[225] As of 2020, the average gross (pre-tax) monthly salary in Lithuania is 1,381 euros translating to 880 euros net (after tax),[226] while average pension is around 400 euros per month.[227] Average wage adjusted for purchasing power parity, is $2,202 per month, one of the lowest in EU.[228] Although, cost of living in the country also is sufficiently less with the price level for household final consumption expenditure (HFCE) – 63, being 39% lower than EU average – 102 in 2016.[229]

Lithuania has a flat tax rate rather than a progressive scheme. According to Eurostat,[230] the personal income tax (15%) and corporate tax (15%) rates in Lithuania are among the lowest in the EU. The country has the lowest implicit rate of tax on capital (9.8%) in the EU. Corporate tax rate in Lithuania is 15% and 5% for small businesses. 7 Free Economic Zones are operating in Lithuania.[231]

Information technology production is growing in the country, reaching 1.9 billion euros in 2016.[232] In 2017 only, 35 [233] FinTech companies came to Lithuania – a result of Lithuanian government and Bank of Lithuania simplified procedures for obtaining licences for the activities of e-money and payment institutions.[234] Europe's first international Blockchain Centre launched in Vilnius in 2018.[235] Lithuania has granted a total of 39 e-money licenses, second in the EU only to the U.K. with 128 licenses. In 2018 Google set up a payment company in Lithuania.[236]

Companies

Biggest companies in Lithuania in 2018, by revenue:[237]

| Rank | Name | Headquarters | Revenue (bil. €) | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ORLEN Lietuva, AB | Mažeikiai | 4.6 | 1,381 |

| 2. | Maxima LT, UAB | Vilnius | 1.6 | 14,670 |

| 3. | Girteka logistics, UAB | Vilnius | 0.764 | 740 |

| 4. | Palink, UAB | Vilnius | 0.649 | 6,631 |

| 5. | ESO, AB | Vilnius | 0.624 | 2,383 |

| 6. | NEO Group, AB | Klaipėda | 0.541 | 223 |

| 7. | Viada LT, UAB | Vilnius | 0.520 | 1,120 |

| 8. | Sanitex, UAB | Kaunas | 0.500 | 1,299 |

| 9. | Norfos mažmena, UAB | Vilnius | 0.469 | 3,284 |

| 10. | Circle K Lietuva, UAB | Vilnius | 0.464 | 864 |

Agriculture

Agriculture in Lithuania dates to the Neolithic period, about 3,000 to 1,000 BC. It has been one of Lithuania's most important occupations for many centuries.[239] Lithuania's accession to the European Union in 2004 ushered in a new agricultural era. The EU pursues a very high standard of food safety and purity. In 1999, the Seimas (parliament) of Lithuania adopted a Law on Product Safety, and in 2000 it adopted a Law on Food.[240][241] The reform of the agricultural market has been carried out on the basis of these two laws.

In 2016, agricultural production was made for 2.29 billion euros in Lithuania. Cereal crops occupied the largest part of it (5709,7 tons), other significant types were sugar beets (933,9 tons), rapeseed (392,5 tons) and potatoes (340,2 tons). Products for 4385,2 million euros were exported from Lithuania to the foreign markets, of which products for 3165,2 million euros were Lithuanian origin. Export of agricultural and food products accounted for 19.4% of all exports of goods from the country.[242]

Organic farming is constantly becoming more popular in Lithuania. The status of organic growers and producers in the country is granted by the public body Ekoagros. In 2016, there were 2539 such farms that occupied 225541,78 hectares. Of these, 43,13% were cereals, 31,22% were perennial grasses, 13,9% were leguminous crops and 11,75% were others.[243]

Science and technology

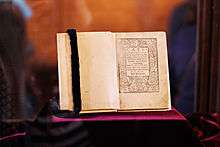

Foundation of the University of Vilnius in 1579 was a major factor of establishing local scientist community in Lithuania and making connections with other universities and scientists of Europe. Georg Forster, Jean-Emmanuel Gilibert, Johann Peter Frank and many other visiting scientists have worked at University of Vilnius. Lithuanian bajoras and Grand Duchy of Lithuania artillery expert Kazimieras Simonavičius is a pioneer of rocketry, who has published Artis Magnae Artilleriae in 1650 that for over two centuries was used in Europe as a basic artillery manual and contains a large chapter on caliber, construction, production and properties of rockets (for military and civil purposes), including multistage rockets, batteries of rockets, and rockets with delta wing stabilizers.[244][245] A botanist Jurgis Pabrėža (1771-1849), created first systematic guide of Lithuanian flora Taislius auguminis (Botany), written in Samogitian dialect, the Latin-Lithuanian dictionary of plant names, first Lithuanian textbook of geography.

During the Interwar period humanitarian and social scientists emerged such as Vosylius Sezemanas, Levas Karsavinas, Mykolas Römeris. Due to the World Wars, Lithuanian science and scientists suffered heavily from the occupants, however some of them reached a world-class achievements in their lifetime. Most notably, Antanas Gustaitis, Vytautas Graičiūnas, Marija Gimbutas, Birutė Galdikas, A. J. Kliorė, Algirdas Julius Greimas, medievalist Jurgis Baltrušaitis, Algirdas Antanas Avižienis.[246][247][248][249][250] Jonas Kubilius, long-term rector of the University of Vilnius is known for works in Probabilistic number theory, Kubilius model, Theorem of Kubilius and Turán–Kubilius inequality bear his name. Jonas Kubilius successfully resisted attempts to Russify the University of Vilnius.[251]

Nowadays, the country is among moderate innovators group in the International Innovation Index.[252] and in the European Innovation Scoreboard ranked 15th among EU countries.[253] Lasers and biotechnology are flagship fields of the Lithuanian science and high tech industry.[254][255] Lithuanian "Šviesos konversija" (Light Conversion) has developed a femtosecond laser system that has 80% marketshare worldwide, and is used in DNA research, ophthalmological surgeries, nanotech industry and science.[256][257] Vilnius University Laser Research Center has developed one of the most powerful femtosecond lasers in the world dedicated primarily to oncological diseases.[258] In 1963, Vytautas Straižys and his coworkers created Vilnius photometric system that is used in astronomy.[259] Noninvasive intracranial pressure and blood flow measuring devices were developed by KTU scientist A. Ragauskas.[260] K.Pyragas contributed to Control of chaos with his way of delayed feedback control – Pyragas method. Kavli Prize laureate Virginijus Šikšnys is known for his discoveries in CRISPR field – invention of CRISPR-Cas9.[261][262]

Lithuania has launched three satellites to space: LitSat-1, Lituanica SAT-1 and LituanicaSAT-2.[263] Lithuanian Museum of Ethnocosmology and Molėtai Astronomical Observatory is located in Kulionys.[264] 15 R&D institutions are members of Lithuanian Space Association; Lithuania is a cooperating state with European Space Agency.[265][266] Rimantas Stankevičius is the only ethnically Lithuanian astronaut.[267]

Lithuania in 2018 became Associated Member State of CERN.[268] Two CERN incubators in Vilnius and Kaunas will be hosted.[269]

Most advanced scientific research in Lithuania is being conducted at the Life Sciences Center,[270] Center For Physical Sciences and Technology.[271]

As of 2016 calculations, yearly growth of Lithuania's biotech and life science sector was 22% over the past 5 years. 16 academic institutions, 15 R&D centres (science parks and innovation valleys) and more than 370 manufacturers operate in the Lithuanian life science and biotech industry.[272]

In 2008 the Valley development programme was started aiming to upgrade Lithuanian scientific research infrastructure and encourage business and science cooperation. Five R&D Valleys were launched – Jūrinis (maritime technologies), Nemunas (agro, bioenergy, forestry), Saulėtekis (laser and light, semiconductor), Santara (biotechnology, medicine), Santaka (sustainable chemistry and pharmacy).[273] Lithuanian Innovation Center is created to provide support for innovations and research institutions.[274]

Tourism

Statistics of 2016 showed that 1.49 million tourists from foreign countries visited Lithuania and spent at least one night in the country. The largest number of tourists came from Germany (174,8 thousand), Belarus (171,9 thousand), Russia (150,6 thousand), Poland (148,4 thousand), Latvia (134,4 thousand), Ukraine (84,0 thousand), and the UK (58,2 thousand).

The total contribution of Travel & Tourism to country GDP was EUR 2,005.5mn, 5.3% of GDP in 2016, and is forecast to rise by 7.3% in 2017, and to rise by 4.2% pa to EUR 3,243.5mn, 6.7% of GDP in 2027.[275] Hot air ballooning is very popular in Lithuania, especially in Vilnius and Trakai. Bicycle tourism is growing, especially in Lithuanian Seaside Cycle Route. EuroVelo routes EV10, EV11, EV13 go through Lithuania. Total length of bicycle tracks amounts to 3769 km (of which 1988 km is asphalt pavement).[276]

Nemunas Delta Regional Park and Žuvintas biosphere reserve are known for birdwatching.[277]

Domestic tourism has been on the rise as well. Currently there are up to 1000 places of attraction in Lithuania. Most tourists visit the big cities—Vilnius, Klaipėda, and Kaunas, seaside resorts, such as Neringa, Palanga, and Spa towns – Druskininkai, Birštonas.[278]

Infrastructure

Communication

Lithuania has a well developed communications infrastructure. The country has 2,8 million citizens[279] and 5 million SIM cards.[280] The largest LTE (4G) mobile network covers 97% of Lithuania's territory.[281] Usage of fixed phone lines has been rapidly decreasing due to rapid expansion of mobile-cellular services.[282]

In 2017, Lithuania was top 30 in the world by average mobile broadband speeds and top 20 by average fixed broadband speeds.[283] Lithuania was also top 7 in 2017 in the List of countries by 4G LTE penetration. In 2016, Lithuania was ranked 17th in United Nations' e-participation index.[284][285]

There are four TIER III datacenters in Lithuania.[286] Lithuania is 44th globally ranked country on data center density according to Cloudscene.[287]

Long-term project (2005–2013) – Development of Rural Areas Broadband Network (RAIN) was started with the objective to provide residents, state and municipal authorities and businesses with fibre-optic broadband access in rural areas. RAIN infrastructure allows 51 communications operators to provide network services to their clients. The project was funded by the European Union and the Lithuanian government.[288][289] 72% of Lithuanian households have access to internet, a number which in 2017 was among EU's lowest[290] and in 2016 ranked 97th by CIA World Factbook.[291] Number of households with internet access is expected to increase and reach 77% by 2021.[292] Almost 50% of Lithuanians had smartphones in 2016, a number that is expected to increase to 65% by 2022.[293] Lithuania has the highest FTTH (Fiber to the home) penetration rate in Europe (36.8% in September 2016) according to FTTH Council Europe.[294]

Transport

.png)

Lithuania received its first railway connection in the middle of the 19th century, when the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway was constructed. It included a stretch from Daugavpils via Vilnius and Kaunas to Virbalis. The first and only still operating tunnel was completed in 1860.