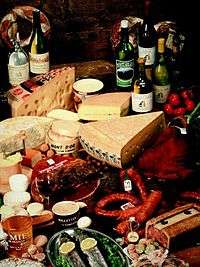

Gastronomy

Gastronomy is the study of the relationship between food and culture, the art of preparing and serving rich or delicate and appetizing food, the cooking styles of particular regions, and the science of good eating.[1] One who is well versed in gastronomy is called a gastronome, while a gastronomist is one who unites theory and practice in the study of gastronomy. Practical gastronomy is associated with the practice and study of the preparation, production, and service of the various foods and beverages, from countries around the world. Theoretical gastronomy supports practical gastronomy. It is related with a system and process approach, focused on recipes, techniques and cookery books. Food gastronomy is connected with food and beverages and their genesis. Technical gastronomy underpins practical gastronomy, introducing a rigorous approach to evaluation of gastronomic topics.[2][3]

History

Gastronomy involves discovering, tasting, experiencing, researching, understanding and writing about food preparation and the sensory qualities of human nutrition as a whole. It also studies how nutrition interfaces with the broader culture. The biological and chemical basis of cooking has become known as molecular gastronomy, while gastronomy covers a much broader, interdisciplinary ground.

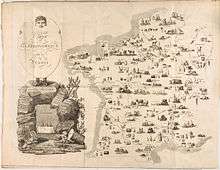

The culinary term appears for the first time in a title in a poem by Joseph Berchoux in 1801 entitled "Gastronomie"[4] Pascal Ory, a French historian, defines gastronomy as the establishment of rules of eating and drinking, an "art of the table", and distinguishes it from good cooking (bonne cuisine) or fine cooking (haute cuisine). Ory traces the origins of gastronomy back to the French reign of Louis XIV when people took interest in developing rules to discriminate between good and bad style and extended their thinking to define good culinary taste. The lavish and sophisticated cuisine and practices of the French court became the culinary model for the French. Alexandre Grimod de La Reynière wrote the gastronomic work Almanach des gourmands (1803), elevating the status of food discourse to a disciplined level based on his views of French tradition and morals. Grimod aimed to reestablish order lost after the revolution and institute gastronomy as a serious subject in France. Grimod expanded gastronomic literature to the three forms of the genre: the guidebook, the gastronomic treatise, and the gourmet periodical. The invention of gastronomic literature coincided with important cultural transformations in France that increased the relevance of the subject. The end of nobility in France changed how people consumed food; fewer wealthy households employed cooks and the new bourgeoisie class wanted to assert their status by consuming elitist food. The emergence of the restaurant satisfied these social needs and provided good food available for popular consumption. The center of culinary excellence in France shifted from Versailles to Paris, a city with a competitive and innovative culinary culture. The culinary commentary of Grimod and other gastronomes influenced the tastes and expectations of consumers in an unprecedented manner as a third party to the consumer-chef interaction.[4]

The French origins of gastronomy explain the widespread use of French terminology in gastronomic literature. Pascal Ory criticizes this literature as conceptually vague; relying heavily on anecdotal evidence; and using confusing, poorly defined terminology. Nevertheless, gastronomy has grown from a marginalized subject in France to a serious and popular interest worldwide.[4]

The derivative gourmet has come into use since the publication of Physiology of Taste (Physiologie du goût) an 1825 cooking treatise by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, a lawyer and politician who aimed to define classic French cuisine. While the work contains some flamboyant recipes, it goes into the theory of preparation of French dishes and hospitality.[5] According to Brillat-Savarin: "Gastronomy is the knowledge and understanding of all that relates to man as he eats. Its purpose is to ensure the conservation of men, using the best food possible."[5][6]

Writings on gastronomy

Many writings on gastronomy throughout the world capture the thoughts and aesthetics of a culture's cuisine during a period in their history. Some works continue to define or influence the contemporary gastronomic thought and cuisine of their respective cultures.

Some additional historical examples:

- Apicius or De re Coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking): A 1st-to-5th-century collection of ancient Roman recipes, often attributed (without clear evidence) to the gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius, it contains instructions for preparing dishes enjoyed by the elite of the time. A new English translation was published in 2009 as Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome.[7]

- Suiyuan Shidan (隨園食單, The Way of Eating, also known in English as Recipes from the Garden of Contentment): An 18th-century manual on Chinese cuisine of Qing dynasty by the poet Yuan Mei, it contains recipes from different social classes at the time along with two chapters on Chinese gastronomic and culinary theory. The first translation into English was completed in 2017.[8]

See also

- Connoisseur

- Gourmand

References

Inline citations

- Oxford Dictionary.

- Gillespie, Cailein; Cousins, John (23 May 2012). European Gastronomy into the 21st Century. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-136-40493-1.

- Cun, Crystal (13 May 2011). "What the Hell Is Gastronomy, Anyway?". Adventures of an Omnomnomnivore in NYC. self-published. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Ory, Pascal (1996). Realms of Memory: Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 445–448.

- Brillat-Savarin (2004).

- Montagné, Prosper (1988) [1938]. Harvey Lang, Jennifer (ed.). Larousse gastronomique (2nd English ("New American") ed. ed.). New York: Crown.CS1 maint: extra text (link) The translation of the Brillat-Savarin quotation is from this work.

- Apicius (2009).

- Yuan (2017).

General references

- Schlosburg, Avi (6 June 2011). "What Is Gastronomy?". Gastronomy Blog. Metropolitan College, Boston University. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Stengel, Kilien (2012). Traité de la gastronomie: Patrimoine et culture (in French). Sang de la Terre.

- Garfield, Leanna (12 February 2016). "Chemistry is bringing chefs 'a new revolution of cooking' — here's what the food of tomorrow looks like". Business Insider.

- Jez, Mojca (24 September 2015). "Molecular Gastronomy: The Food Science". Splice. BioSistemika LLC. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

External links

- Apicius, Marcus Gavius [attributed] (2009) [1st–5th C.]. Starr, Frederick (ed.). De re Coquinaria [Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome]. Translated by Vehling, Joseph Dommers. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 7 August 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) English translation; several formats available.

- Yuan, Mei (2017) [1792]. "隨園食單" [Way of the Eating]. Translated by Chen, Sean Jy-Shyang.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) English translation with original Chinese, in website form with commentaries. Also published in hardback as Recipes from the Garden of Contentment (2018) and trade paperback as The Way of Eating (2019), by the same translator.

- Brillat-Savarin, Jean Anthelme (2004) [1825]. Harris, Steve; Franks, Charles (eds.). The Physiology of Taste: Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy. Translated by Robinson, Fayette (10th ed.). Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 7 August 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) English translation; several formats available.

- Gastronomy Books Digital Collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the US Library of Congress