Car

A car (or automobile) is a wheeled motor vehicle used for transportation. Most definitions of cars say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four tires, and mainly transport people rather than goods.[2][3]

| Car | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification | Vehicle |

| Industry | Various |

| Application | Transportation |

| Fuel source | Gasoline, diesel, natural gas, electric, hydrogen, solar, vegetable oil |

| Powered | Yes |

| Self-propelled | Yes |

| Wheels | 3–4 |

| Axles | 2 |

| Inventor | Karl Benz[1] |

Cars came into global use during the 20th century, and developed economies depend on them. The year 1886 is regarded as the birth year of the modern car when German inventor Karl Benz patented his Benz Patent-Motorwagen. Cars became widely available in the early 20th century. One of the first cars accessible to the masses was the 1908 Model T, an American car manufactured by the Ford Motor Company. Cars were rapidly adopted in the US, where they replaced animal-drawn carriages and carts, but took much longer to be accepted in Western Europe and other parts of the world.

Cars have controls for driving, parking, passenger comfort, and a variety of lights. Over the decades, additional features and controls have been added to vehicles, making them progressively more complex, but also more reliable and easier to operate. These include rear-reversing cameras, air conditioning, navigation systems, and in-car entertainment. Most cars in use in the 2010s are propelled by an internal combustion engine, fueled by the combustion of fossil fuels. Electric cars, which were invented early in the history of the car, became commercially available in the 2000s and are predicted to cost less to buy than gasoline cars before 2025.[4][5] The transition from fossil fuels to electric cars features prominently in most climate change mitigation scenarios.[6]

There are costs and benefits to car use. The costs to the individual include acquiring the vehicle, interest payments (if the car is financed), repairs and maintenance, fuel, depreciation, driving time, parking fees, taxes, and insurance.[7] The costs to society include maintaining roads, land use, road congestion, air pollution, public health, healthcare, and disposing of the vehicle at the end of its life. Traffic collisions are the largest cause of injury-related deaths worldwide.[8]

The personal benefits include on-demand transportation, mobility, independence, and convenience.[9] The societal benefits include economic benefits, such as job and wealth creation from the automotive industry, transportation provision, societal well-being from leisure and travel opportunities, and revenue generation from the taxes. People's ability to move flexibly from place to place has far-reaching implications for the nature of societies.[10] There are around 1 billion cars in use worldwide. The numbers are increasing rapidly, especially in China, India and other newly industrialized countries.[11]

Etymology

The English word car is believed to originate from Latin carrus/carrum "wheeled vehicle" or (via Old North French) Middle English carre "two-wheeled cart," both of which in turn derive from Gaulish karros "chariot."[12][13] It originally referred to any wheeled horse-drawn vehicle, such as a cart, carriage, or wagon.[14][15]

"Motor car," attested from 1895, is the usual formal term in British English.[3] "Autocar," a variant likewise attested from 1895 and literally meaning "self-propelled car," is now considered archaic.[16] "Horseless carriage" is attested from 1895.[17]

"Automobile," a classical compound derived from Ancient Greek autós (αὐτός) "self" and Latin mobilis "movable," entered English from French and was first adopted by the Automobile Club of Great Britain in 1897.[18] It fell out of favour in Britain and is now used chiefly in North America,[19] where the abbreviated form "auto" commonly appears as an adjective in compound formations like "auto industry" and "auto mechanic".[20][21] Both forms are still used in everyday Dutch (auto/automobiel) and German (Auto/Automobil).

History

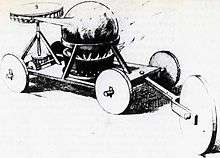

The first working steam-powered vehicle was designed — and quite possibly built — by Ferdinand Verbiest, a Flemish member of a Jesuit mission in China around 1672. It was a 65-cm-long scale-model toy for the Chinese Emperor that was unable to carry a driver or a passenger.[9][22][23] It is not known with certainty if Verbiest's model was successfully built or run.[23]

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot is widely credited with building the first full-scale, self-propelled mechanical vehicle or car in about 1769; he created a steam-powered tricycle.[24] He also constructed two steam tractors for the French Army, one of which is preserved in the French National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts.[25] His inventions were, however, handicapped by problems with water supply and maintaining steam pressure.[25] In 1801, Richard Trevithick built and demonstrated his Puffing Devil road locomotive, believed by many to be the first demonstration of a steam-powered road vehicle. It was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods and was of little practical use.

The development of external combustion engines is detailed as part of the history of the car but often treated separately from the development of true cars. A variety of steam-powered road vehicles were used during the first part of the 19th century, including steam cars, steam buses, phaetons, and steam rollers. Sentiment against them led to the Locomotive Acts of 1865.

In 1807, Nicéphore Niépce and his brother Claude created what was probably the world's first internal combustion engine (which they called a Pyréolophore), but they chose to install it in a boat on the river Saone in France.[26] Coincidentally, in 1807 the Swiss inventor François Isaac de Rivaz designed his own 'de Rivaz internal combustion engine' and used it to develop the world's first vehicle to be powered by such an engine. The Niépces' Pyréolophore was fuelled by a mixture of Lycopodium powder (dried spores of the Lycopodium plant), finely crushed coal dust and resin that were mixed with oil, whereas de Rivaz used a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen.[26] Neither design was very successful, as was the case with others, such as Samuel Brown, Samuel Morey, and Etienne Lenoir with his hippomobile, who each produced vehicles (usually adapted carriages or carts) powered by internal combustion engines.[1]

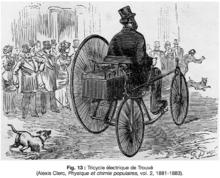

In November 1881, French inventor Gustave Trouvé demonstrated the first working (three-wheeled) car powered by electricity at the International Exposition of Electricity, Paris.[27] Although several other German engineers (including Gottlieb Daimler, Wilhelm Maybach, and Siegfried Marcus) were working on the problem at about the same time, Karl Benz generally is acknowledged as the inventor of the modern car.[1]

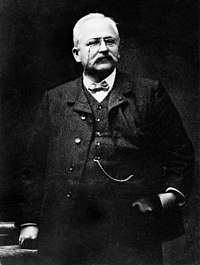

In 1879, Benz was granted a patent for his first engine, which had been designed in 1878. Many of his other inventions made the use of the internal combustion engine feasible for powering a vehicle. His first Motorwagen was built in 1885 in Mannheim, Germany. He was awarded the patent for its invention as of his application on 29 January 1886 (under the auspices of his major company, Benz & Cie., which was founded in 1883). Benz began promotion of the vehicle on 3 July 1886, and about 25 Benz vehicles were sold between 1888 and 1893, when his first four-wheeler was introduced along with a cheaper model. They also were powered with four-stroke engines of his own design. Emile Roger of France, already producing Benz engines under license, now added the Benz car to his line of products. Because France was more open to the early cars, initially more were built and sold in France through Roger than Benz sold in Germany. In August 1888 Bertha Benz, the wife of Karl Benz, undertook the first road trip by car, to prove the road-worthiness of her husband's invention.

In 1896, Benz designed and patented the first internal-combustion flat engine, called boxermotor. During the last years of the nineteenth century, Benz was the largest car company in the world with 572 units produced in 1899 and, because of its size, Benz & Cie., became a joint-stock company. The first motor car in central Europe and one of the first factory-made cars in the world, was produced by Czech company Nesselsdorfer Wagenbau (later renamed to Tatra) in 1897, the Präsident automobil.

Daimler and Maybach founded Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft (DMG) in Cannstatt in 1890, and sold their first car in 1892 under the brand name Daimler. It was a horse-drawn stagecoach built by another manufacturer, which they retrofitted with an engine of their design. By 1895 about 30 vehicles had been built by Daimler and Maybach, either at the Daimler works or in the Hotel Hermann, where they set up shop after disputes with their backers. Benz, Maybach and the Daimler team seem to have been unaware of each other's early work. They never worked together; by the time of the merger of the two companies, Daimler and Maybach were no longer part of DMG. Daimler died in 1900 and later that year, Maybach designed an engine named Daimler-Mercedes that was placed in a specially ordered model built to specifications set by Emil Jellinek. This was a production of a small number of vehicles for Jellinek to race and market in his country. Two years later, in 1902, a new model DMG car was produced and the model was named Mercedes after the Maybach engine, which generated 35 hp. Maybach quit DMG shortly thereafter and opened a business of his own. Rights to the Daimler brand name were sold to other manufacturers.

Karl Benz proposed co-operation between DMG and Benz & Cie. when economic conditions began to deteriorate in Germany following the First World War, but the directors of DMG refused to consider it initially. Negotiations between the two companies resumed several years later when these conditions worsened and, in 1924 they signed an Agreement of Mutual Interest, valid until the year 2000. Both enterprises standardized design, production, purchasing, and sales and they advertised or marketed their car models jointly, although keeping their respective brands. On 28 June 1926, Benz & Cie. and DMG finally merged as the Daimler-Benz company, baptizing all of its cars Mercedes Benz, as a brand honoring the most important model of the DMG cars, the Maybach design later referred to as the 1902 Mercedes-35 hp, along with the Benz name. Karl Benz remained a member of the board of directors of Daimler-Benz until his death in 1929, and at times, his two sons also participated in the management of the company.

In 1890, Émile Levassor and Armand Peugeot of France began producing vehicles with Daimler engines, and so laid the foundation of the automotive industry in France. In 1891, Auguste Doriot and his Peugeot colleague Louis Rigoulot completed the longest trip by a gasoline-powered vehicle when their self-designed and built Daimler powered Peugeot Type 3 completed 2,100 km (1,300 miles) from Valentigney to Paris and Brest and back again. They were attached to the first Paris–Brest–Paris bicycle race, but finished 6 days after the winning cyclist, Charles Terront.

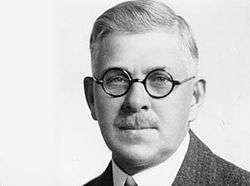

The first design for an American car with a gasoline internal combustion engine was made in 1877 by George Selden of Rochester, New York. Selden applied for a patent for a car in 1879, but the patent application expired because the vehicle was never built. After a delay of sixteen years and a series of attachments to his application, on 5 November 1895, Selden was granted a United States patent (U.S. Patent 549,160) for a two-stroke car engine, which hindered, more than encouraged, development of cars in the United States. His patent was challenged by Henry Ford and others, and overturned in 1911.

In 1893, the first running, gasoline-powered American car was built and road-tested by the Duryea brothers of Springfield, Massachusetts. The first public run of the Duryea Motor Wagon took place on 21 September 1893, on Taylor Street in Metro Center Springfield.[28][29] The Studebaker Automobile Company, subsidiary of a long-established wagon and coach manufacturer, started to build cars in 1897[30]:p.66 and commenced sales of electric vehicles in 1902 and gasoline vehicles in 1904.[31]

In Britain, there had been several attempts to build steam cars with varying degrees of success, with Thomas Rickett even attempting a production run in 1860.[32] Santler from Malvern is recognized by the Veteran Car Club of Great Britain as having made the first gasoline-powered car in the country in 1894,[33] followed by Frederick William Lanchester in 1895, but these were both one-offs.[33] The first production vehicles in Great Britain came from the Daimler Company, a company founded by Harry J. Lawson in 1896, after purchasing the right to use the name of the engines. Lawson's company made its first car in 1897, and they bore the name Daimler.[33]

In 1892, German engineer Rudolf Diesel was granted a patent for a "New Rational Combustion Engine". In 1897, he built the first diesel engine.[1] Steam-, electric-, and gasoline-powered vehicles competed for decades, with gasoline internal combustion engines achieving dominance in the 1910s. Although various pistonless rotary engine designs have attempted to compete with the conventional piston and crankshaft design, only Mazda's version of the Wankel engine has had more than very limited success.

All in all, it is estimated that over 100,000 patents created the modern automobile and motorcycle.[34]

Mass production

Large-scale, production-line manufacturing of affordable cars was started by Ransom Olds in 1901 at his Oldsmobile factory in Lansing, Michigan and based upon stationary assembly line techniques pioneered by Marc Isambard Brunel at the Portsmouth Block Mills, England, in 1802. The assembly line style of mass production and interchangeable parts had been pioneered in the U.S. by Thomas Blanchard in 1821, at the Springfield Armory in Springfield, Massachusetts.[35] This concept was greatly expanded by Henry Ford, beginning in 1913 with the world's first moving assembly line for cars at the Highland Park Ford Plant.

As a result, Ford's cars came off the line in fifteen-minute intervals, much faster than previous methods, increasing productivity eightfold, while using less manpower (from 12.5-man-hours to 1 hour 33 minutes).[36] It was so successful, paint became a bottleneck. Only Japan black would dry fast enough, forcing the company to drop the variety of colors available before 1913, until fast-drying Duco lacquer was developed in 1926. This is the source of Ford's apocryphal remark, "any color as long as it's black".[36] In 1914, an assembly line worker could buy a Model T with four months' pay.[36]

Ford's complex safety procedures—especially assigning each worker to a specific location instead of allowing them to roam about—dramatically reduced the rate of injury. The combination of high wages and high efficiency is called "Fordism," and was copied by most major industries. The efficiency gains from the assembly line also coincided with the economic rise of the United States. The assembly line forced workers to work at a certain pace with very repetitive motions which led to more output per worker while other countries were using less productive methods.

In the automotive industry, its success was dominating, and quickly spread worldwide seeing the founding of Ford France and Ford Britain in 1911, Ford Denmark 1923, Ford Germany 1925; in 1921, Citroen was the first native European manufacturer to adopt the production method. Soon, companies had to have assembly lines, or risk going broke; by 1930, 250 companies which did not, had disappeared.[36]

Development of automotive technology was rapid, due in part to the hundreds of small manufacturers competing to gain the world's attention. Key developments included electric ignition and the electric self-starter (both by Charles Kettering, for the Cadillac Motor Company in 1910–1911), independent suspension, and four-wheel brakes.

Since the 1920s, nearly all cars have been mass-produced to meet market needs, so marketing plans often have heavily influenced car design. It was Alfred P. Sloan who established the idea of different makes of cars produced by one company, called the General Motors Companion Make Program, so that buyers could "move up" as their fortunes improved.

Reflecting the rapid pace of change, makes shared parts with one another so larger production volume resulted in lower costs for each price range. For example, in the 1930s, LaSalles, sold by Cadillac, used cheaper mechanical parts made by Oldsmobile; in the 1950s, Chevrolet shared hood, doors, roof, and windows with Pontiac; by the 1990s, corporate powertrains and shared platforms (with interchangeable brakes, suspension, and other parts) were common. Even so, only major makers could afford high costs, and even companies with decades of production, such as Apperson, Cole, Dorris, Haynes, or Premier, could not manage: of some two hundred American car makers in existence in 1920, only 43 survived in 1930, and with the Great Depression, by 1940, only 17 of those were left.[36]

In Europe, much the same would happen. Morris set up its production line at Cowley in 1924, and soon outsold Ford, while beginning in 1923 to follow Ford's practice of vertical integration, buying Hotchkiss (engines), Wrigley (gearboxes), and Osberton (radiators), for instance, as well as competitors, such as Wolseley: in 1925, Morris had 41% of total British car production. Most British small-car assemblers, from Abbey to Xtra, had gone under. Citroen did the same in France, coming to cars in 1919; between them and other cheap cars in reply such as Renault's 10CV and Peugeot's 5CV, they produced 550,000 cars in 1925, and Mors, Hurtu, and others could not compete.[36] Germany's first mass-manufactured car, the Opel 4PS Laubfrosch (Tree Frog), came off the line at Russelsheim in 1924, soon making Opel the top car builder in Germany, with 37.5% of the market.[36]

In Japan, car production was very limited before World War II. Only a handful of companies were producing vehicles in limited numbers, and these were small, three-wheeled for commercial uses, like Daihatsu, or were the result of partnering with European companies, like Isuzu building the Wolseley A-9 in 1922. Mitsubishi was also partnered with Fiat and built the Mitsubishi Model A based on a Fiat vehicle. Toyota, Nissan, Suzuki, Mazda, and Honda began as companies producing non-automotive products before the war, switching to car production during the 1950s. Kiichiro Toyoda's decision to take Toyoda Loom Works into automobile manufacturing would create what would eventually become Toyota Motor Corporation, the largest automobile manufacturer in the world. Subaru, meanwhile, was formed from a conglomerate of six companies who banded together as Fuji Heavy Industries, as a result of having been broken up under keiretsu legislation.

Fuel and propulsion technologies

According to the European Environment Agency, the transport sector is a major contributor to air pollution, noise pollution and climate change.[37]

Most cars in use in the 2010s run on gasoline burnt in an internal combustion engine (ICE). The International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers says that, in countries that mandate low sulfur gasoline, gasoline-fuelled cars built to late 2010s standards (such as Euro-6) emit very little local air pollution.[38][39] Some cities ban older gasoline-fuelled cars and some countries plan to ban sales in future. However some environmental groups say this phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles must be brought forward to limit climate change. Production of gasoline fueled cars peaked in 2017.[40][41]

Other hydrocarbon fossil fuels also burnt by deflagration (rather than detonation) in ICE cars include diesel, Autogas and CNG. Removal of fossil fuel subsidies,[42][43] concerns about oil dependence, tightening environmental laws and restrictions on greenhouse gas emissions are propelling work on alternative power systems for cars. This includes hybrid vehicles, plug-in electric vehicles and hydrogen vehicles. 2.1 million light electric vehicles (of all types but mainly cars) were sold in 2018, over half in China: this was an increase of 64% on the previous year, giving a global total on the road of 5.4 million.[44] Vehicles using alternative fuels such as ethanol flexible-fuel vehicles and natural gas vehicles are also gaining popularity in some countries. Cars for racing or speed records have sometimes employed jet or rocket engines, but these are impractical for common use.

Oil consumption has increased rapidly in the 20th and 21st centuries because there are more cars; the 1985–2003 oil glut even fuelled the sales of low-economy vehicles in OECD countries. The BRIC countries are adding to this consumption.

User interface

Cars are equipped with controls used for driving, passenger comfort and safety, normally operated by a combination of the use of feet and hands, and occasionally by voice on 21st century cars. These controls include a steering wheel, pedals for operating the brakes and controlling the car's speed (and, in a manual transmission car, a clutch pedal), a shift lever or stick for changing gears, and a number of buttons and dials for turning on lights, ventilation and other functions. Modern cars' controls are now standardized, such as the location for the accelerator and brake, but this was not always the case. Controls are evolving in response to new technologies, for example the electric car and the integration of mobile communications.

Some of the original controls are no longer required. For example, all cars once had controls for the choke valve, clutch, ignition timing, and a crank instead of an electric starter. However new controls have also been added to vehicles, making them more complex. These include air conditioning, navigation systems, and in car entertainment. Another trend is the replacement of physical knobs and switches by secondary controls with touchscreen controls such as BMW's iDrive and Ford's MyFord Touch. Another change is that while early cars' pedals were physically linked to the brake mechanism and throttle, in the 2010s, cars have increasingly replaced these physical linkages with electronic controls.

Lighting

Cars are typically fitted with multiple types of lights. These include headlights, which are used to illuminate the way ahead and make the car visible to other users, so that the vehicle can be used at night; in some jurisdictions, daytime running lights; red brake lights to indicate when the brakes are applied; amber turn signal lights to indicate the turn intentions of the driver; white-colored reverse lights to illuminate the area behind the car (and indicate that the driver will be or is reversing); and on some vehicles, additional lights (e.g., side marker lights) to increase the visibility of the car. Interior lights on the ceiling of the car are usually fitted for the driver and passengers. Some vehicles also have a trunk light and, more rarely, an engine compartment light.

Weight

During the late 20th and early 21st century cars increased in weight due to batteries,[46] modern steel safety cages, anti-lock brakes, airbags, and "more-powerful—if more-efficient—engines"[47] and, as of 2019, typically weigh between 1 and 3 tonnes.[48] Heavier cars are safer for the driver from a crash perspective, but more dangerous for other vehicles and road users.[47] The weight of a car influences fuel consumption and performance, with more weight resulting in increased fuel consumption and decreased performance. The SmartFortwo, a small city car, weighs 750–795 kg (1,655–1,755 lb). Heavier cars include full-size cars, SUVs and extended-length SUVs like the Suburban.

According to research conducted by Julian Allwood of the University of Cambridge, global energy use could be greatly reduced by using lighter cars, and an average weight of 500 kg (1,100 lb) has been said to be well achievable.[49] In some competitions such as the Shell Eco Marathon, average car weights of 45 kg (99 lb) have also been achieved.[50] These cars are only single-seaters (still falling within the definition of a car, although 4-seater cars are more common), but they nevertheless demonstrate the amount by which car weights could still be reduced, and the subsequent lower fuel use (i.e. up to a fuel use of 2560 km/l).[51]

Seating and body style

Most cars are designed to carry multiple occupants, often with four or five seats. Cars with five seats typically seat two passengers in the front and three in the rear. Full-size cars and large sport utility vehicles can often carry six, seven, or more occupants depending on the arrangement of the seats. On the other hand, sports cars are most often designed with only two seats. The differing needs for passenger capacity and their luggage or cargo space has resulted in the availability of a large variety of body styles to meet individual consumer requirements that include, among others, the sedan/saloon, hatchback, station wagon/estate, and minivan.

Safety

Traffic collisions are the largest cause of injury-related deaths worldwide.[8] Mary Ward became one of the first documented car fatalities in 1869 in Parsonstown, Ireland,[52] and Henry Bliss one of the United States' first pedestrian car casualties in 1899 in New York City.[53] There are now standard tests for safety in new cars, such as the EuroNCAP and the US NCAP tests,[54] and insurance-industry-backed tests by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS).[55]

Costs and benefits

The costs of car usage, which may include the cost of: acquiring the vehicle, repairs and auto maintenance, fuel, depreciation, driving time, parking fees, taxes, and insurance,[7] are weighed against the cost of the alternatives, and the value of the benefits – perceived and real – of vehicle usage. The benefits may include on-demand transportation, mobility, independence and convenience.[9] During the 1920s, cars had another benefit: "[c]ouples finally had a way to head off on unchaperoned dates, plus they had a private space to snuggle up close at the end of the night."[57]

Similarly the costs to society of car use may include; maintaining roads, land use, air pollution, road congestion, public health, health care, and of disposing of the vehicle at the end of its life; and can be balanced against the value of the benefits to society that car use generates. Societal benefits may include: economy benefits, such as job and wealth creation, of car production and maintenance, transportation provision, society wellbeing derived from leisure and travel opportunities, and revenue generation from the tax opportunities. The ability of humans to move flexibly from place to place has far-reaching implications for the nature of societies.[10]

Environmental impact

Cars are a major cause of urban air pollution,[58] with all types of cars producing dust from brakes, tyres and road wear.[59] As of 2018 the average diesel car has a worse effect on air quality than the average gasoline car[60] But both gasoline and diesel cars pollute more than electric cars.[61] While there are different ways to power cars most rely on gasoline or diesel, and they consume almost a quarter of world oil production as of 2019.[40] In 2018 passenger road vehicles emitted 3.6 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide.[62] As of 2019, due to greenhouse gases emitted during battery production, electric cars must be driven tens of thousands of kilometers before their lifecycle carbon emissions are less than fossil fuel cars:[63] but this is expected to improve in future due to longer lasting[64] batteries being produced in larger factories,[65] and lower carbon electricity. Many governments are using fiscal policies, such as road tax, to discourage the purchase and use of more polluting cars;[66] and many cities are doing the same with low-emission zones.[67] Fuel taxes may act as an incentive for the production of more efficient, hence less polluting, car designs (e.g. hybrid vehicles) and the development of alternative fuels. High fuel taxes or cultural change may provide a strong incentive for consumers to purchase lighter, smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, or to not drive.[67]

The lifetime of a car built in the 2020s is expected to be about 16 years, or about 2 million kilometres (1.2 million miles) if driven a lot.[68] According to the International Energy Agency fuel economy improved 0.7% in 2017, but an annual improvement of 3.7% is needed to meet the Global Fuel Economy Initiative 2030 target.[69] The increase in sales of SUVs is bad for fuel economy.[40] Many cities in Europe, have banned older fossil fuel cars and all fossil fuel vehicles will be banned in Amsterdam from 2030.[70] Many Chinese cities limit licensing of fossil fuel cars,[71] and many countries plan to stop selling them between 2025 and 2050.[72]

The manufacture of vehicles is resource intensive, and many manufacturers now report on the environmental performance of their factories, including energy usage, waste and water consumption.[73] Manufacturing each kWh of battery emits a similar amount of carbon as burning through one full tank of gasoline.[74] The growth in popularity of the car allowed cities to sprawl, therefore encouraging more travel by car resulting in inactivity and obesity, which in turn can lead to increased risk of a variety of diseases.[75]

Animals and plants are often negatively impacted by cars via habitat destruction and pollution. Over the lifetime of the average car the "loss of habitat potential" may be over 50,000 m2 (540,000 sq ft) based on primary production correlations.[76] Animals are also killed every year on roads by cars, referred to as roadkill. More recent road developments are including significant environmental mitigation in their designs, such as green bridges (designed to allow wildlife crossings) and creating wildlife corridors.

Growth in the popularity of vehicles and commuting has led to traffic congestion. Moscow, Istanbul, Bogota, Mexico City and Sao Paulo were the world's most congested cities in 2018 according to INRIX, a data analytics company.[77]

Emerging car technologies

Although intensive development of conventional battery electric vehicles is continuing into the 2020s,[78] other car propulsion technologies that are under development include wheel hub motors,[79] wireless charging,[80] hydrogen cars,[81] and hydrogen/electric hybrids.[82] Research into alternative forms of power includes using ammonia instead of hydrogen in fuel cells.[83]

New materials[84] which may replace steel car bodies include duralumin, fiberglass, carbon fiber, biocomposites, and carbon nanotubes. Telematics technology is allowing more and more people to share cars, on a pay-as-you-go basis, through car share and carpool schemes. Communication is also evolving due to connected car systems.[85]

Autonomous car

Fully autonomous vehicles, also known as driverless cars, already exist in prototype (such as the Google driverless car), but have a long way to go before they are in general use.

Open source development

There have been several projects aiming to develop a car on the principles of open design, an approach to designing in which the plans for the machinery and systems are publicly shared, often without monetary compensation. The projects include OScar, Riversimple (through 40fires.org)[86] and c,mm,n.[87] None of the projects have reached significant success in terms of developing a car as a whole both from hardware and software perspective and no mass production ready open-source based design have been introduced as of late 2009. Some car hacking through on-board diagnostics (OBD) has been done so far.[88]

Car sharing

Car-share arrangements and carpooling are also increasingly popular, in the US and Europe.[89] For example, in the US, some car-sharing services have experienced double-digit growth in revenue and membership growth between 2006 and 2007. Services like car sharing offering a residents to "share" a vehicle rather than own a car in already congested neighborhoods.[90]

Industry

The automotive industry designs, develops, manufactures, markets, and sells the world's motor vehicles, more than three-quarters of which are cars. In 2018 there were 70 million cars manufactured worldwide,[91] down 2 million from the previous year.[92]

The automotive industry in China produces by far the most (24 million in 2018), followed by Japan (8 million), Germany (5 million) and India (4 million).[91] The largest market is China, followed by the USA.

Around the world there are about a billion cars on the road;[93] they burn over a trillion liters of gasoline and diesel fuel yearly, consuming about 50 EJ (nearly 300 terawatt-hours) of energy.[94] The numbers of cars are increasing rapidly in China and India.[11] In the opinion of some, urban transport systems based around the car have proved unsustainable, consuming excessive energy, affecting the health of populations, and delivering a declining level of service despite increasing investment. Many of these negative impacts fall disproportionately on those social groups who are also least likely to own and drive cars.[95][96] The sustainable transport movement focuses on solutions to these problems. The car industry is also facing increasing competition from the public transport sector, as some people re-evaluate their private vehicle usage.

Alternatives

Established alternatives for some aspects of car use include public transport such as buses, trolleybuses, trains, subways, tramways, light rail, cycling, and walking. Bicycle sharing systems have been established in China and many European cities, including Copenhagen and Amsterdam. Similar programs have been developed in large US cities.[98][99] Additional individual modes of transport, such as personal rapid transit could serve as an alternative to cars if they prove to be socially accepted.[100]

Other meanings

The term motorcar was formerly also used in the context of electrified rail systems to denote a car which functions as a small locomotive but also provides space for passengers and baggage. These locomotive cars were often used on suburban routes by both interurban and intercity railroad systems.[101]

See also

References

- Stein, Ralph (1967). The Automobile Book. Paul Hamlyn.

- Fowler, H.W.; Fowler, F.G., eds. (1976). Pocket Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198611134.

- "motor car, n." OED Online. Oxford University Press. September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "EV Price Parity Coming Soon, Claims VW Executive". CleanTechnica. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Electric V Petrol - British Gas". Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Factcheck: How electric vehicles help to tackle climate change". Carbon Brief. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- "Car Operating Costs". RACV. Archived from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- Peden, Margie; Scurfield, Richard; Sleet, David; Mohan, Dinesh; Hyder, Adnan A.; Jarawan, Eva; Mathers, Colin, eds. (2004). World report on road traffic injury prevention. World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-156260-9. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Setright, L. J. K. (2004). Drive On!: A Social History of the Motor Car. Granta Books. ISBN 1-86207-698-7.

- Jakle, John A.; Sculle, Keith A. (2004). Lots of Parking: Land Use in a Car Culture. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2266-6.

- "Automobile Industry Introduction". Plunkett Research. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- "Car". (etymology). Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Wayne State University and The Detroit Public Library Present "Changing Face of the Auto Industry"". Wayne State University. 28 June 2003. Archived from the original on 28 June 2003.

- "car, n.1". OED Online. Oxford University Press. September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "A dictionary of the Welsh language" (PDF). University of Wales. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "auto-, comb. form2". OED Online. Oxford University Press. September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Definition of horseless carriage". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Prospective Arrangements", The Times, p. 13, 4 December 1897

- "automobile, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press. September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Definition of "auto"". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Definition of auto". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "1679-1681–R P Verbiest's Steam Chariot". History of the Automobile: origin to 1900. Hergé. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- "A brief note on Ferdinand Verbiest". Curious Expeditions. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2008. – Note that the vehicle pictured is the 20th century diecast model made by Brumm, of a later vehicle, not a model based on Verbiest's plans.

- Encyclopædia Britannica "Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot".

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- speos.fr. "Niepce Museum, Other Inventions". Niepce.house.museum. Archived from the original on 20 December 2005. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Wakefield, Ernest H. (1994). History of the Electric Automobile. Society of Automotive Engineers. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-56091-299-5.

- "The First Car – A History of the Automobile". Ausbcomp.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "The Duryea Brothers – Automobile History". Inventors.about.com. 16 September 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Longstreet, Stephen. A Century on Wheels: The Story of Studebaker. New York: Henry Holt. p. 121. 1st edn., 1952.

- Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.178.

- Burgess Wise, D. (1970). Veteran and Vintage Cars. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-00283-7.

- Georgano, N. (2000). Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile. London: HMSO. ISBN 1-57958-293-1.

- Jerina, Nataša G. (May 2014). "Turin Charter ratified by FIVA". TICCIH. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Industrialization of American Society". Engr.sjsu.edu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Georgano, G. N. (2000). Vintage Cars 1886 to 1930. Sweden: AB Nordbok. ISBN 1-85501-926-4.

- "Transport greenhouse gas emissions". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "14 Countries and Territory State Move Up in Top 100 Ranking on Gasoline Sulfur Limits". Stratas Advisors. 30 July 2018.

- "'Among the worst in OECD': Australia's addiction to cheap, dirty petrol". The Guardian. 4 February 2019.

- "October: Growing preference for SUVs challenges emissions reductions in passenger car mark". www.iea.org. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Bloomberg NEF Electric Vehicle Outlook 2019". Bloomberg NEF. 15 May 2019.

- "Govt to completely lift fuel subsidies in 2020: minister". Egypt Independent. 8 January 2019.

- "Why the Rouhani administration must eliminate energy subsidies". Al-Monitor. 9 December 2018.

- "Global EV Sales for 2018 – Final Results". EV Volumes. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Used 2008 Chevrolet Suburban Features & Specs". Edmunds. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "How much do electric cars weigh? | EV Archive". Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Lowrey, Annie (27 June 2011). "Your Big Car Is Killing Me". Slate. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- Sellén, Magnus (2 August 2019). "How much does a Car Weigh? - [Weight List by Car Model & Type]". Mechanic Base. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Possible global energy reducstion". New Scientist. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Robarts, Stu (26 May 2016). "Behind the wheel of a super-efficient Shell Eco-marathon car". New Atlas. Australia. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Andy Green's 8000-mile/gallon car". Mindfully.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Mary Ward 1827–1869". Universityscience.ie. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- "CityStreets – Bliss plaque". Archived from the original on 26 August 2006.

- "SaferCar.gov – NHTSA". Archived from the original on 27 July 2004.

- "Insurance Institute for Highway Safety".

- Fran Tonkiss. Space, the city and social theory: social relations and urban forms. Polity, 2005

- Anthony, Ariana (9 May 2013). "Dating in the 1920s: Lipstick, Booze and the Origins of Slut-Shaming | HowAboutWe". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Sengupta, Somini; Popovich, Nadja (14 November 2019). "Cities Worldwide Are Reimagining Their Relationship With Cars". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Smith, Luke John (18 July 2019). "The UK air pollution problem that won't be solved with switch to electric cars". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Leggett, Theo (21 January 2018). "Reality Check: Are diesel cars always the most harmful?". Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "EEA report confirms: electric cars are better for climate and air quality". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Tracking Transport – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Estimation of CO2 Emissions of Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle and Battery Electric Vehicle Using LCA". Sustainability.

- "carbonfootprint.com - Electric Vehicles". www.carbonfootprint.com. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Tomorrow is Good: why German automobile club study is the anti-electric lobby at its finest". Innovation Origins. 3 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "A Review and Comparative Analysis of Fiscal Policies Associated with New Passenger Vehicle CO2 Emissions" (PDF). International Council on Clean Transportation. February 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Sherwood, Harriet (26 January 2020). "Brighton, Bristol, York ... city centres signal the end of the road for cars". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "Tesla supplier ready to make million-mile battery". BBC News. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Fuel economy". www.iea.org. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Boffey, Daniel (3 May 2019). "Amsterdam to ban petrol and diesel cars and motorbikes by 2030". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Lambert, Fred (6 June 2019). "China boosts electric car sales by removing license plate quotas". Electrek. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Schwanen, Tim (19 September 2019). "The five major challenges facing electric vehicles". Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Volvo's carbon-free car factory". Ends Report. October 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Group, Drax. "Drax Electric Insights". Drax Electric Insights. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Our Ailing Communities". Metropolis Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- Ball, Jeffrey (9 March 2009). "Six Products, Six Carbon Footprints". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Newman, Katelyn (12 February 2019). "Cities With the World's Worst Traffic Congestion". US News. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "EV battery research projects get £55m funding boost". Air Quality News. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Schmidt, Bridie (14 June 2019). "Turn on a penny: Hyundai developing electric cars with motors inside the wheels". The Driven. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Wireless electric car charging gets cash boost". 9 July 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "China's Hydrogen Vehicle Dream Chased With $17 Billion of Funding". 23 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Motor Mouth: Is Mazda's e-TPV the perfect electric vehicle?". Driving. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Ammonia for fuel cells". phys.org. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Vyas, Kashyap (3 October 2018). "This New Material Can Transform the Car Manufacturing Industry". Interesting Engineering. Turkey. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Inside Uniti's plan to build the iPhone of EVs". GreenMotor.co.uk. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "FortyFires: Main". 40fires.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- "open source mobility: home". c,mm,n. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- "Geek My Ride presentation at linux.conf.au 2009". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- "Global Automotive Consumer Study - exploring consumer preferences and mobility choices in Europe" (PDF). Deloitte. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Flexcar Expands to Philadelphia". Green Car Congress. 2 April 2007.

- "2018 Production Statistics". International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

- "2017 Production Statistics". International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

- "PC World Vehicles in Use" (PDF). International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Global Transportation Energy Consumption: Examination of Scenarios to 2040 using ITEDD" (PDF). Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- World Health Organisation, Europe. "Health effects of transport". Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "GLOBAL ACTION FOR HEALTHY STREETS: ANNUAL REPORT 2018" (PDF). FiA Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Larsen, Janet (25 April 2013). "Bike-Sharing Programs Hit the Streets in Over 500 Cities Worldwide". Earth Policy Institute. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- "About Bike Share Programs". Tech Bikes MIT. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Cambell, Charlie (2 April 2018). "The Trouble with Sharing: China's Bike Fever Has Reached Saturation Point". Time. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Kay, Jane Holtz (1998). Asphalt Nation: how the automobile took over America, and how we can take it back. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21620-2.

- "atchison_177". Laparks.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

Further reading

- Halberstam, David (1986). The Reckoning. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-688-04838-2.

- Kay, Jane Holtz (1997). Asphalt nation : how the automobile took over America, and how we can take it back. New York: Crown. ISBN 0-517-58702-5.

- Williams, Heathcote (1991). Autogeddon. New York: Arcade. ISBN 1-55970-176-5.

- Sachs, Wolfgang (1992). For love of the automobile: looking back into the history of our desires. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06878-5.

- Margolius, Ivan (2020). "What is an automobile?". The Automobile. 37 (11): 48–52. ISSN 0955-1328.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Automobile. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Car |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up car in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

%2C_r%C3%A9am%C3%A9nagement%2C_2012-04-05_39.jpg)