Florence Cathedral

Florence Cathedral, formally the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (Italian pronunciation: [katteˈdraːle di ˈsanta maˈriːa del ˈfjoːre]; in English "Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower"), is the cathedral of Florence, Italy (Italian: Duomo di Firenze). It was begun in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was structurally completed by 1436, with the dome engineered by Filippo Brunelleschi.[1] The exterior of the basilica is faced with polychrome marble panels in various shades of green and pink, bordered by white, and has an elaborate 19th-century Gothic Revival façade by Emilio De Fabris.

| Florence Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower | |

| |

Brunelleschi's Dome, the nave, and Giotto's Campanile of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore as seen from Michelangelo Hill at night. | |

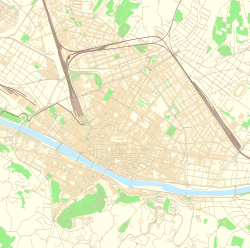

Florence Cathedral Location in Florence, Italy | |

| 43°46′23.1″N 11°15′22.4″E | |

| Location | Florence, Tuscany |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Tradition | Latin Rite |

| Website | Duomo Firenze |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral, minor basilica |

| Consecrated | 1436 |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Italian Gothic, Renaissance, Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 9 September 1296 |

| Completed | 1436 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 153 metres (502 ft) |

| Width | 90 metres (300 ft) |

| Nave width | 38 metres (125 ft) |

| Height | 114.5 metres (376 ft) |

| Floor area | 8,300 square metres (89,000 sq ft) |

| Materials | Marble, brick |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Florence |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Giuseppe Betori |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Florence |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1982 (6th session) |

| Reference no. | 174 |

| State Party | Italy |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The cathedral complex, in Piazza del Duomo, includes the Baptistery and Giotto's Campanile. These three buildings are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site covering the historic centre of Florence and are a major tourist attraction of Tuscany. The basilica is one of Italy's largest churches, and until the development of new structural materials in the modern era, the dome was the largest in the world. It remains the largest brick dome ever constructed.

The cathedral is the mother church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Florence, whose archbishop is Giuseppe Betori.

History

Santa Maria del Fiore was built on the site of Florence's second cathedral dedicated to Saint Reparata[2]; the first was the Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze, the first building of which was consecrated as a church in 393 by St. Ambrose of Milan.[3] The ancient structure, founded in the early 5th century and having undergone many repairs, was crumbling with age, according to the 14th-century Nuova Cronica of Giovanni Villani,[4] and was no longer large enough to serve the growing population of the city.[4] Other major Tuscan cities had undertaken ambitious reconstructions of their cathedrals during the Late Medieval period, such as Pisa and particularly Siena where the enormous proposed extensions were never completed.

City council approved the design of Arnolfo di Cambio for the new church in 1294.[5] Di Cambio was also architect of the church of Santa Croce and the Palazzo Vecchio.[6][7] He designed three wide naves ending under the octagonal dome, with the middle nave covering the area of Santa Reparata. The first stone was laid on 9 September 1296, by Cardinal Valeriana, the first papal legate ever sent to Florence. The building of this vast project was to last 140 years; Arnolfo's plan for the eastern end, although maintained in concept, was greatly expanded in size.

After Arnolfo died in 1302, work on the cathedral slowed for almost 50 years. When the relics of Saint Zenobius were discovered in 1330 in Santa Reparata, the project gained a new impetus. In 1331, the Arte della Lana, the guild of wool merchants, took over patronage for the construction of the cathedral and in 1334 appointed Giotto to oversee the work. Assisted by Andrea Pisano, Giotto continued di Cambio's design. His major accomplishment was the building of the campanile. When Giotto died on 8 January 1337, Andrea Pisano continued the building until work was halted due to the Black Death in 1348.

In 1349, work resumed on the cathedral under a series of architects, starting with Francesco Talenti, who finished the campanile and enlarged the overall project to include the apse and the side chapels. In 1359, Talenti was succeeded by Giovanni di Lapo Ghini (1360–1369) who divided the center nave in four square bays. Other architects were Alberto Arnoldi, Giovanni d'Ambrogio, Neri di Fioravante and Andrea Orcagna. By 1375, the old church Santa Reparata was pulled down. The nave was finished by 1380, and only the dome remained incomplete until 1418.

On 19 August 1418[8], the Arte della Lana announced an architectural design competition for erecting Neri's dome. The two main competitors were two master goldsmiths, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, the latter of whom was supported by Cosimo de Medici. Ghiberti had been the winner of a competition for a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistery in 1401 and lifelong competition between the two remained sharp. Brunelleschi won and received the commission.[9]

Ghiberti, appointed coadjutor, drew a salary equal to Brunelleschi's and, though neither was awarded the announced prize of 200 florins, was promised equal credit, although he spent most of his time on other projects. When Brunelleschi became ill, or feigned illness, the project was briefly in the hands of Ghiberti. But Ghiberti soon had to admit that the whole project was beyond him. In 1423, Brunelleschi was back in charge and took over sole responsibility.[10]

In 1420 Work on the dome was started and it was completed in 1436. The cathedral was consecrated by Pope Eugene IV on 25 March 1436, (the first day of the year according to the Florentine calendar). It was the first 'octagonal' dome in history to be built without a temporary wooden supporting frame. It was one of the most impressive projects of the Renaissance. During the consecration in 1436, Guillaume Dufay's motet Nuper rosarum flores was performed.

The decoration of the exterior of the cathedral, begun in the 14th century, was not completed until 1887, when the polychrome marble façade was completed with the design of Emilio De Fabris. The floor of the church was relaid in marble tiles in the 16th century.

The exterior walls are faced in alternate vertical and horizontal bands of polychrome marble from Carrara (white), Prato (green), Siena (red), Lavenza and a few other places. These marble bands had to repeat the already existing bands on the walls of the earlier adjacent baptistery the Battistero di San Giovanni and Giotto's Bell Tower. There are two side doors: the Doors of the Canonici (south side) and the Door of the Mandorla (north side) with sculptures by Nanni di Banco, Donatello, and Jacopo della Quercia. The six side windows, notable for their delicate tracery and ornaments, are separated by pilasters. Only the four windows closest to the transept admit light; the other two are merely ornamental. The clerestory windows are round, a common feature in Italian Gothic.

During its long history, this cathedral has been the seat of the Council of Florence (1439), heard the preachings of Girolamo Savonarola and witnessed the murder of Giuliano di Piero de' Medici on Sunday, 26 April 1478 (with Lorenzo Il Magnifico barely escaping death), in the Pazzi conspiracy.

Exterior

Plan and structure

The cathedral of Florence is built as a basilica, having a wide central nave of four square bays, with an aisle on either side. The chancel and transepts are of identical polygonal plan, separated by two smaller polygonal chapels. The whole plan forms a Latin cross. The nave and aisles are separated by wide pointed Gothic arches resting on composite piers.

The dimensions of the building are enormous: building area 8,300 square metres (89,340 square feet), length 153 metres (502 feet), width 38 metres (125 feet), width at the crossing 90 metres (300 feet). The height of the arches in the aisles is 23 metres (75 feet). The height of the dome is 114.5 metres (375.7 feet).[11] It has the third tallest dome in the world.

Planned Sculpture for the exterior

The Overseers of the Office of Works of Florence Cathedral the Arte della Lana, had plans to commission a series of twelve large Old Testament sculptures for the buttresses of the cathedral.[12] Donatello, then in his early twenties, was commissioned to carve a statue of David in 1408, to top one of the buttresses of Florence Cathedral, though it was never placed there. Nanni di Banco was commissioned to carve a marble statue of Isaiah, at the same scale, in the same year. One of the statues was lifted into place in 1409, but was found to be too small to be easily visible from the ground and was taken down; both statues then languished in the workshop of the opera for several years.[13][14][15] In 1410 Donatello made the first of the statues, a figure of Joshua in terracotta. In 1409-1411 Donatello made a statue of Saint John the Evangelist which until 1588 was in a niche of the old cathedral façade. A figure of Hercules, also in terracotta, was commissioned from the Florentine sculptor Agostino di Duccio in 1463 and was made perhaps under Donatello's direction.[16] A statue of David by Michelangelo was completed 1501-1504 although it could not be placed on the Butteresss because of its six ton weight. In 2010 a fiberglass replica of "David" was placed for one day on the Florence cathedral.

- Donatello first version of David (1408–1409). Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. Height 191 cm.

- Possible Statue of "Isaiah" by Nanni di Banco

Donatello's colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist. 1409-1411

Donatello's colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist. 1409-1411- A Fiberglass replica of Michaelangelo's David statue [seen from the north]. This was the original placement planned for the statue.

Dome

After a hundred years of construction and by the beginning of the 15th century, the structure was still missing its dome. The basic features of the dome had been designed by Arnolfo di Cambio in 1296. His brick model, 4.6 metres (15.1 feet) high, 9.2 metres (30.2 feet) long, was standing in a side aisle of the unfinished building, and had long been sacrosanct.[17] It called for an octagonal dome higher and wider than any that had ever been built, with no external buttresses to keep it from spreading and falling under its own weight.

| External video | |

|---|---|

The commitment to reject traditional Gothic buttresses had been made when Neri di Fioravanti's model was chosen over a competing one by Giovanni di Lapo Ghini.[19] That architectural choice, in 1367, was one of the first events of the Italian Renaissance, marking a break with the Medieval Gothic style and a return to the classic Mediterranean dome. Italian architects regarded Gothic flying buttresses as ugly makeshifts. Furthermore, the use of buttresses was forbidden in Florence, as the style was favored by central Italy's traditional enemies to the north.[20] Neri's model depicted a massive inner dome, open at the top to admit light, like Rome's Pantheon, partly supported by the inner dome, but enclosed in a thinner outer shell, to keep out the weather. It was to stand on an unbuttressed octagonal drum. Neri's dome would need an internal defense against spreading (hoop stress), but none had yet been designed.

The building of such a masonry dome posed many technical problems. Brunelleschi looked to the great dome of the Pantheon in Rome for solutions. The dome of the Pantheon is a single shell of concrete, the formula for which had long since been forgotten. The Pantheon had employed structural centring to support the concrete dome while it cured.[21] This could not be the solution in the case of a dome this size and would put the church out of use. For the height and breadth of the dome designed by Neri, starting 52 metres (171 ft) above the floor and spanning 44 metres (144 ft), there was not enough timber in Tuscany to build the scaffolding and forms.[22] Brunelleschi chose to follow such design and employed a double shell, made of sandstone and marble. Brunelleschi would have to build the dome out of brick, due to its light weight compared to stone and being easier to form, and with nothing under it during construction. To illustrate his proposed structural plan, he constructed a wooden and brick model with the help of Donatello and Nanni di Banco, a model which is still displayed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. The model served as a guide for the craftsmen, but was intentionally incomplete, so as to ensure Brunelleschi's control over the construction.

.jpg)

Brunelleschi's solutions were ingenious. The spreading problem was solved by a set of four internal horizontal stone and iron chains, serving as barrel hoops, embedded within the inner dome: one at the top, one at the bottom, with the remaining two evenly spaced between them. A fifth chain, made of wood, was placed between the first and second of the stone chains. Since the dome was octagonal rather than round, a simple chain, squeezing the dome like a barrel hoop, would have put all its pressure on the eight corners of the dome. The chains needed to be rigid octagons, stiff enough to hold their shape, so as not to deform the dome as they held it together.[18]

Each of Brunelleschi's stone chains was built like an octagonal railroad track with parallel rails and cross ties, all made of sandstone beams 43 centimetres (17 in) in diameter and no more than 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) long. The rails were connected end-to-end with lead-glazed iron splices. The cross ties and rails were notched together and then covered with the bricks and mortar of the inner dome. The cross ties of the bottom chain can be seen protruding from the drum at the base of the dome. The others are hidden. Each stone chain was supposed to be reinforced with a standard iron chain made of interlocking links, but a magnetic survey conducted in the 1970s failed to detect any evidence of iron chains, which if they exist are deeply embedded in the thick masonry walls. Brunelleschi also included vertical "ribs" set on the corners of the octagon, curving towards the center point. The ribs, 4 metres (13 ft) deep, are supported by 16 concealed ribs radiating from center.[23] The ribs had slits to take beams that supported platforms, thus allowing the work to progress upward without the need for scaffolding.[24]

A circular masonry dome can be built without supports, called centering, because each course of bricks is a horizontal arch that resists compression. In Florence, the octagonal inner dome was thick enough for an imaginary circle to be embedded in it at each level, a feature that would hold the dome up eventually, but could not hold the bricks in place while the mortar was still wet. Brunelleschi used a herringbone brick pattern to transfer the weight of the freshly laid bricks to the nearest vertical ribs of the non-circular dome.[25][26][27][28]

The outer dome was not thick enough to contain embedded horizontal circles, being only 60 centimetres (2 ft) thick at the base and 30 centimetres (1 ft) thick at the top. To create such circles, Brunelleschi thickened the outer dome at the inside of its corners at nine different elevations, creating nine masonry rings, which can be observed today from the space between the two domes. To counteract hoop stress, the outer dome relies entirely on its attachment to the inner dome and has no embedded chains.[29]

A modern understanding of physical laws and the mathematical tools for calculating stresses were centuries in the future. Brunelleschi, like all cathedral builders, had to rely on intuition and whatever he could learn from the large scale models he built. To lift 37,000 tons of material, including over 4 million bricks, he invented hoisting machines and lewissons for hoisting large stones. These specially designed machines and his structural innovations were Brunelleschi's chief contribution to architecture. Although he was executing an aesthetic plan made half a century earlier, it is his name, rather than Neri's, that is commonly associated with the dome.

Brunelleschi's ability to crown the dome with a lantern was questioned and he had to undergo another competition, even though there had been evidence that Brunelleschi had been working on a design for a lantern for the upper part of the dome. The evidence is shown in the curvature, which was made steeper than the original model.[30] He was declared the winner over his competitors Lorenzo Ghiberti and Antonio Ciaccheri. His design (now on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo) was for an octagonal lantern with eight radiating buttresses and eight high arched windows. Construction of the lantern was begun a few months before his death in 1446. Then, for 15 years, little progress was possible, due to alterations by several architects. The lantern was finally completed by Brunelleschi's friend Michelozzo in 1461. The conical roof was crowned with a gilt copper ball and cross, containing holy relics, by Verrocchio in 1469. This brings the total height of the dome and lantern to 114.5 metres (376 ft). This copper ball was struck by lightning on 17 July 1600 and fell down. It was replaced by an even larger one two years later.

The commission for this gilt copper ball [atop the lantern] went to the sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio, in whose workshop there was at this time a young apprentice named Leonardo da Vinci. Fascinated by Filippo's [Brunelleschi's] machines, which Verrocchio used to hoist the ball, Leonardo made a series of sketches of them and, as a result, is often given credit for their invention.[31]

Leonardo might have also participated in the design of the bronze ball, as stated in the G manuscript of Paris "Remember the way we soldered the ball of Santa Maria del Fiore".[32]

The decorations of the drum gallery by Baccio d'Agnolo were never finished after being disapproved by no one less than Michelangelo.

A huge statue of Brunelleschi now sits outside the Palazzo dei Canonici in the Piazza del Duomo, looking thoughtfully up towards his greatest achievement, the dome that would forever dominate the panorama of Florence. It is still the largest masonry dome in the world.[33]

The building of the cathedral had started in 1296 with the design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was completed in 1469 with the placing of Verrochio's copper ball atop the lantern. But the façade was still unfinished and would remain so until the 19th century.

Facade

The original façade, designed by Arnolfo di Cambio and usually attributed to Giotto, was actually begun twenty years after Giotto's death. A mid-15th-century pen-and-ink drawing of this so-called Giotto's façade is visible in the Codex Rustici, and in the drawing of Bernardino Poccetti in 1587, both on display in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo. This façade was the collective work of several artists, among them Andrea Orcagna and Taddeo Gaddi. This original façade was completed in only its lower portion and then left unfinished. It was dismantled in 1587–1588 by the Medici court architect Bernardo Buontalenti, ordered by Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici, as it appeared totally outmoded in Renaissance times. Some of the original sculptures are on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo, behind the cathedral. Others are now in the Berlin Museum and in the Louvre.

The competition for a new façade turned into a huge corruption scandal. The wooden model for the façade of Buontalenti is on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo. A few new designs had been proposed in later years, but the models (of Giovanni Antonio Dosio, Giovanni de' Medici with Alessandro Pieroni and Giambologna) were not accepted. The façade was then left bare until the 19th century.

_-_n._9537_-_Firenze_-_Porta_maggiore_della_Cattedrale%2C_prof._Augusto_Passaglia.jpg)

In 1864, a competition held to design a new façade was won by Emilio De Fabris (1808–1883) in 1871. Work began in 1876 and was completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto's bell tower and the Baptistery, but some think it is excessively decorated.

The whole façade is dedicated to the Mother of Christ.

Main Portal

The three huge bronze doors date from 1899 to 1903. They are adorned with scenes from the life of the Madonna. The mosaics in the lunettes above the doors were designed by Niccolò Barabino. They represent (from left to right): Charity among the founders of Florentine philanthropic institutions; Christ enthroned with Mary and John the Baptist; and Florentine artisans, merchants and humanists. The pediment above the central portal contains a half-relief by Tito Sarrocchi of Mary enthroned holding a flowered scepter. Giuseppe Cassioli sculpted the right-hand door.

On top of the façade is a series of niches with the twelve Apostles with, in the middle, the Madonna with Child. Between the rose window and the tympanum, there is a gallery with busts of great Florentine artists.

Interior

.jpg)

The Gothic interior is vast and gives an empty impression. The relative bareness of the church corresponds with the austerity of religious life, as preached by Girolamo Savonarola.

Many decorations in the church have been lost in the course of time, or have been transferred to the Museum Opera del Duomo, such as the magnificent cantorial pulpits (the singing galleries for the choristers) of Luca della Robbia and Donatello.

As this cathedral was built with funds from the public, some important works of art in this church honour illustrious men and military leaders of Florence:[34]

• Lorenzo Ghiberti had a large artistic impact on the cathedral. Ghiberti worked with Filippo Brunelleschi on the cathedral for eighteen years and had a large number of projects on almost the whole east end. Some of his works were the stained glass designs, the bronze shrine of Saint Zenobius and marble revetments on the outside of the cathedral.

- Dante Before the City of Florence by Domenico di Michelino (1465). This painting is especially interesting because it shows us, apart from scenes of the Divine Comedy, a view on Florence in 1465, a Florence such as Dante himself could not have seen in his time.

- Funerary Monument to Sir John Hawkwood by Paolo Uccello (1436). This almost monochrome fresco, transferred to canvas in the 19th century, is painted in terra verde, a color closest to the patina of bronze.

- Equestrian statue of Niccolò da Tolentino by Andrea del Castagno (1456). This fresco, transferred on canvas in the 19th century, in the same style as the previous one, is painted in a color resembling marble. However, it is more richly decorated and gives more the impression of movement. Both frescoes portray the condottieri as heroic figures riding triumphantly. Both painters had problems when applying in painting the new rules of perspective to foreshortening: they used two unifying points, one for the horse and one for the pedestal, instead a single unifying point.

- Busts of Giotto (by Benedetto da Maiano), Brunelleschi (by Buggiano – 1447), Marsilio Ficino, and Antonio Squarcialupi (a most famous organist). These busts all date from the 15th and the 16th centuries.

Above the main door is the colossal clock face with fresco portraits of four Prophets or Evangelists by Paolo Uccello (1443). This one-handed liturgical clock shows the 24 hours of the hora italica (Italian time), a period of time ending with sunset at 24 hours. This timetable was used until the 18th century. This is one of the few clocks from that time that still exist and are in working order.[34]

The church is particularly notable for its 44 stained glass windows, the largest undertaking of this kind in Italy in the 14th and 15th century. The windows in the aisles and in the transept depict saints from the Old and the New Testament, while the circular windows in the drum of the dome or above the entrance depict Christ and Mary. They are the work of the greatest Florentine artists of their times, such as Donatello, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Paolo Uccello and Andrea del Castagno.[34]

Christ crowning Mary as Queen, the stained-glass circular window above the clock, with a rich range of coloring, was designed by Gaddo Gaddi in the early 14th century.

Donatello designed the stained-glass window (Coronation of the Virgin) in the drum of the dome (the only one that can be seen from the nave).

The beautiful funeral monument of Antonio d'Orso (1323), bishop of Florence, was made by Tino da Camaino, the most important funeral sculptor of his time.

The monumental crucifix, behind the Bishop's Chair at the high altar, is by Benedetto da Maiano (1495–1497). The choir enclosure is the work of the famous Bartolommeo Bandinelli. The ten-paneled bronze doors of the sacristy were made by Luca della Robbia, who has also two glazed terracotta works inside the sacristy: Angel with Candlestick and Resurrection of Christ.[34]

In the back of the middle of the three apses is the altar of Saint Zanobius, first bishop of Florence. Its silver shrine, a masterpiece of Ghiberti, contains the urn with his relics. The central compartment shows us one of his miracles, the reviving of a dead child. Above this shrine is the painting Last Supper by the lesser-known Giovanni Balducci. There was also a glass-paste mosaic panel The Bust of Saint Zanobius by the 16th-century miniaturist Monte di Giovanni, but it is now on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo.[34]

Many decorations date from the 16th-century patronage of the Grand Dukes, such as the pavement in colored marble, attributed to Baccio d'Agnolo and Francesco da Sangallo (1520–26). Some pieces of marble from the façade were used, topside down, in the flooring (as was shown by the restoration of the floor after the 1966 flooding).[34]

It was suggested that the interior of the 45 metre (147 ft) wide dome should be covered with a mosaic decoration to make the most of the available light coming through the circular windows of the drum and through the lantern. Brunelleschi had proposed the vault to glimmer with resplendent gold, but his death in 1446 put an end to this project, and the walls of the dome were whitewashed. Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici decided to have the dome painted with a representation of The Last Judgment. This enormous work, 3,600 metres² (38 750 ft²) of painted surface, was started in 1568 by Giorgio Vasari and Federico Zuccari and would last till 1579. The upper portion, near the lantern, representing The 24 Elders of Apoc. 4 was finished by Vasari before his death in 1574. Federico Zuccari and a number of collaborators, such as Domenico Cresti, finished the other portions: (from top to bottom) Choirs of Angels; Christ, Mary and Saints; Virtues, Gifts of the Holy Spirit and Beatitudes; and at the bottom of the cupola: Capital Sins and Hell. These frescoes are considered Zuccari's greatest work. But the quality of the work is uneven because of the input of different artists and the different techniques. Vasari had used true fresco, while Zuccari had painted in secco. During the restoration work, which ended in 1995, the entire pictorial cycle of The Last Judgment was photographed with specially designed equipment and all the information collected in a catalogue. All the restoration information along with reconstructed images of the frescos were stored and managed in the Thesaurus Florentinus computer system.[35][36]

Crypt

The cathedral underwent difficult excavations between 1965 and 1974. The archaeological history of this huge area was reconstructed through the work of Dr. Franklin Toker: remains of Roman houses, an early Christian pavement, ruins of the former cathedral of Santa Reparata and successive enlargements of this church. Close to the entrance, in the part of the crypt open to the public, is the tomb of Brunelleschi. While its location is prominent, the actual tomb is simple and humble. That the architect was permitted such a prestigious burial place is proof of the high esteem he was given by the Florentines.

Other burials

- Zenobius of Florence

- Conrad II of Italy

- Giovanni Benelli

- Filippo Brunelleschi

- Giotto di Bondone

- Pope Nicholas II

- Pope Stephen IX

- John Hawkwood

See also

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

- List of largest domes in the world

- List of tallest domes in the world

- Santa Reparata, Florence

- Inferno, 2013 Dan Brown novel

- History of Medieval Arabic and Western European domes

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

Notes

- Ermengem, Kristiaan Van. "Duomo di Firenze, Florence". A View On Cities. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Bartlett, pp. 36–37; according to Bartlett, the people of Florence continued to call the cathedral by its former name for some time after reconstruction.

- Tarihi, Güncelleme (23 May 2018). "Michelangelo Rönesans döneminde Floransanın önde gelen Medici Ailesinin özel bir isteği üzerine hangisini yapmıştır". Haber46 (in Turkish). Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Barlett, 36.

- Haines, Margaret (1989). "Brunelleschi and Bureaucracy: The Tradition of Public Patronage at the Florentine Cathedral". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 3: 89–115. doi:10.2307/4603662. JSTOR 4603662.

- Krén, Emil; Marx, Daniel. "View of the nave and choir by ARNOLFO DI CAMBIO". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Sannio, Simone (12 January 2017). "Inside the House of Medici (Part II): Palazzo Vecchio". L'Italo-Americano. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8027-1366-7.

- Zucconi, Guido (1995). Florence: An Architectural Guide. San Giovanni Lupatoto, Vr, Italy: Arsenale Editrice srl. ISBN 978-88-7743-147-9.

- King, pp. 76–79.

- "Santa Maria Del Fiore Church (Dome) Firenze Italy". En.firenze-online.com. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Charles Seymour, Jr. "Homo Magnus et Albus: the Quattrocento Background for Michelangelo's David of 1501–04," Stil und Überlieferung in der Kunst des Abendlandes, Berlin, 1967, II, 96–105.

- Janson, pp. 3–7

- Pope-Hennessey, John (1958) Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London, pp. 6–7

- Poeschke, p. 27.

- Seymour, 100–101.

- King, p. 10

- "Brunelleschi's Dome". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- King, p. 9.

- King, p. 7.

- Lancaster, Lynne (2005) Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context, Cambridge University Press, p. 44

- PBS' The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, Birth of a Dynasty (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FFDJK8jmms at the 20:15 mark)

- Stevenson, Niel (2007) Architecture Explained. ISBN 0756628687. pp. 36–37.

- King, pp. 70–73.

- King, p. 97.

- Mueller, Tom (10 February 2014). "Mystery of Florence's Cathedral Dome May Be Solved". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- NationalGeographic.com 2014-02 Il Duomo Tom Mueller

- NationalGeographic.com 2014-02 Il Doumo Design Video

- King, pp. 105–107.

- Gartner, Peter, Filippo Brunelleschi 1377–1446, p 95.

- King, p. 69.

- Paolo Galluzzi, "Leonard de Vinci, engineer and architect", p. 50

- Figures vary. archINFORM gives a 45 m wide tambour, while Santa Maria del Fiore at Structurae gives a 43 m diameter of the cupola, others as little as 42 m.

- King, Ross (2001). Brunelleschi's Dome: The Story of the great Cathedral of Florence. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-8027-1366-1.

- As referenced in "Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore: il cantiere di restauro 1980–1995" by Cristina Acidini Luchinat and Riccardo Dalla Negra published by Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato (Roma) in 1995 (ISBN 8824039561)

- Thesaurus Florentinus project page (in Italian), Soprintendenza ai Beni Architettonici e Paesaggisitici di Firenze, Ministero dei Beni Culturali

References

- Bartlett, Kenneth R. (1992). The Civilization of the Italian Renaissance. Toronto: D.C. Heath and Company. ISBN 0-669-20900-7 (Paperback).

- King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 9781620401941.

- Jepson, Tim (2001). The National Geographic Traveler, Florence & Tuscany. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-90-215-9720-1.

- Henry A. Millon (ed.) (1994). Italian Renaissance Architecture: from Brunelleschi to Michelangelo. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27921-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Montrésor, Carlo (2000). The Opera del Duomo, Museum in Florence. Mandragora.

- Suro, Roberto (28 July 1987). "Cracks in a Great Dome in Florence May Point to Impending Disaster". New York Times. p. C3. Retrieved 26 February 2010.

- Tacconi, Marica S. Cathedral and Civic Ritual in Late Medieval and Renaissance Florence: The Service Books of Santa Maria del Fiore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-521-81704-2

- Wirtz, Rolf C. (2005). Kunst & Architektur, Florenz. Könemann. ISBN 3-8331-1576-9.

- Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore: il cantiere di restauro 1980–1995, a cura di Cristina Acidini Luchinat e Riccardo Dalla Negra. Istituto poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato (Roma). 1995. ISBN 978-88-240-3956-7. Library of Congress permalink

- Devémy, Jean-François (2013). Sur les traces de Filippo Brunelleschi, l'invention de la coupole de Santa Maria del Fiore à Florence. Suresnes: Les Editions du Net. ISBN 978-2-312-01329-9. (in line presentation)

- Gärtner, Peter J. (1998). Filippo Brunelleschi 1377-1446. Köln : Könemann. ISBN 978-3-8290-0241-7.

Further reading

- "The Great Cathedral Mystery", PBS Nova TV documentary, 12 February 2014

- Hunt, Don, "Secrets of the Duomo", Journal, Issue 2, 2014, International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers

- Mueller, Tom, "Brunelleschi’s Dome: How did a hot-tempered goldsmith with no formal architectural training create the most miraculous edifice of the Renaissance?", National Geographic magazine, February 2014

- Ricci, Massimo, Il genio di Brunelleschi e la costruzione della Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore, Livorno : Casa Editrice Sillabe S.r.l., April 2014. (The genius of Filippo Brunelleschi and the construction of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore). ISBN 978-88-8347-691-4. The book is the result of forty years of research on the secret technique with which Brunelleschi built the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Ricci makes the case for the dome being an inverted arch and uses a herringbone pattern (spina a pesce) for the dome's bricks.

- Vereycken, Karel, "The Secrets of the Florentine Dome", Schiller Institute, 2013. (Translation from the French, "Les secrets du dôme de Florence", la revue Fusion, n° 96, Mai, Juin 2003)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Maria del Fiore (Florence). |

- Official website

- L'Opera del Duomo, Firenze

- Brunelleschi's Dome – en

- "The Cathedral". The Florence Art Guide. 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- Museums in Florence – Cathedral and Giotto Belltower

- Horner, Susan; Horner, Joanna (27 December 2005). "Chapter III: The Cathedral – Exterior". Walks in Florence. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- NGM.NationalGeographic.com 2014– 02 Il Duomo 360 Panorama View Interactive

- NGM.NationalGeographic.com 2014-02 Il Duomo Cutaway Interactive

- ngm.nationalgeographic.com 2014-02 ll Duomo Piazza 360 degree panorama interactive

- ngm.nationalgeographic.com 2014-02 Il Duomo Compared to other Domes Interactive