Modern philosophy

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school (and thus should not be confused with Modernism), although there are certain assumptions common to much of it, which helps to distinguish it from earlier philosophy.[1]

| History of Western philosophy |

|---|

|

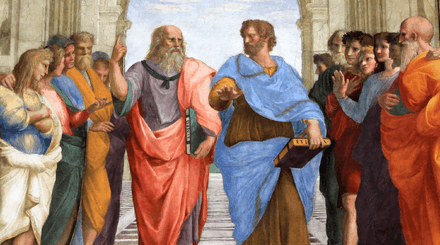

| The School of Athens fresco by Raphael |

| Western philosophy |

|

|

| See also |

The 17th and early 20th centuries roughly mark the beginning and the end of modern philosophy. How much of the Renaissance should be included is a matter for dispute; likewise modernity may or may not have ended in the twentieth century and been replaced by postmodernity. How one decides these questions will determine the scope of one's use of the term "modern philosophy."

Modern Western philosophy

How much of Renaissance intellectual history is part of modern philosophy is disputed:[2] the Early Renaissance is often considered less modern and more medieval compared to the later High Renaissance. By the 17th and 18th centuries the major figures in philosophy of mind, epistemology, and metaphysics were roughly divided into two main groups. The "Rationalists," mostly in France and Germany, argued all knowledge must begin from certain "innate ideas" in the mind. Major rationalists were Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, and Nicolas Malebranche. The "Empiricists," by contrast, held that knowledge must begin with sensory experience. Major figures in this line of thought are John Locke, George Berkeley, and David Hume (These are retrospective categories, for which Kant is largely responsible). Ethics and political philosophy are usually not subsumed under these categories, though all these philosophers worked in ethics, in their own distinctive styles. Other important figures in political philosophy include Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

In the late eighteenth century Immanuel Kant set forth a groundbreaking philosophical system which claimed to bring unity to rationalism and empiricism. Whether or not he was right, he did not entirely succeed in ending philosophical dispute. Kant sparked a storm of philosophical work in Germany in the early nineteenth century, beginning with German idealism. The characteristic theme of idealism was that the world and the mind equally must be understood according to the same categories; it culminated in the work of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who among many other things said that "The real is rational; the rational is real."

Hegel's work was carried in many directions by his followers and critics. Karl Marx appropriated both Hegel's philosophy of history and the empirical ethics dominant in Britain, transforming Hegel's ideas into a strictly materialist form, setting the grounds for the development of a science of society. Søren Kierkegaard, in contrast, dismissed all systematic philosophy as an inadequate guide to life and meaning. For Kierkegaard, life is meant to be lived, not a mystery to be solved. Arthur Schopenhauer took idealism to the conclusion that the world was nothing but the futile endless interplay of images and desires, and advocated atheism and pessimism. Schopenhauer's ideas were taken up and transformed by Nietzsche, who seized upon their various dismissals of the world to proclaim "God is dead" and to reject all systematic philosophy and all striving for a fixed truth transcending the individual. Nietzsche found in this not grounds for pessimism, but the possibility of a new kind of freedom.

19th-century British philosophy came increasingly to be dominated by strands of neo-Hegelian thought, and as a reaction against this, figures such as Bertrand Russell and George Edward Moore began moving in the direction of analytic philosophy, which was essentially an updating of traditional empiricism to accommodate the new developments in logic of the German mathematician Gottlob Frege.

Renaissance philosophy

Renaissance humanism emphasized the value of human beings (see Oration on the Dignity of Man) and opposed dogma and scholasticism. This new interest in human activities led to the development of political science with The Prince of Niccolò Machiavelli.[3] Humanists differed from Medieval scholars also because they saw the natural world as mathematically ordered and pluralistic, instead of thinking of it in terms of purposes and goals. Renaissance philosophy is perhaps best explained by two propositions made by Leonardo da Vinci in his notebooks:

- All of our knowledge has its origins in our perceptions

- There is no certainty where one can neither apply any of the mathematical sciences nor any of those which are based upon the mathematical sciences.

In a similar way, Galileo Galilei based his scientific method on experiments but also developed mathematical methods for application to problems in physics. These two ways to conceive human knowledge formed the background for the principle of Empiricism and Rationalism respectively.[4]

Renaissance philosophers

- Pico della Mirandola

- Nicolas of Cusa

- Giordano Bruno

- Galileo Galilei

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Michel de Montaigne

- Francisco Suárez

Rationalism

Modern philosophy traditionally begins with René Descartes and his dictum "I think, therefore I am". In the early seventeenth century the bulk of philosophy was dominated by Scholasticism, written by theologians and drawing upon Plato, Aristotle, and early Church writings. Descartes argued that many predominant Scholastic metaphysical doctrines were meaningless or false. In short, he proposed to begin philosophy from scratch. In his most important work, Meditations on First Philosophy, he attempts just this, over six brief essays. He tries to set aside as much as he possibly can of all his beliefs, to determine what if anything he knows for certain. He finds that he can doubt nearly everything: the reality of physical objects, God, his memories, history, science, even mathematics, but he cannot doubt that he is, in fact, doubting. He knows what he is thinking about, even if it is not true, and he knows that he is there thinking about it. From this basis he builds his knowledge back up again. He finds that some of the ideas he has could not have originated from him alone, but only from God; he proves that God exists. He then demonstrates that God would not allow him to be systematically deceived about everything; in essence, he vindicates ordinary methods of science and reasoning, as fallible but not false.

Rationalists

- Christian Wolff

- René Descartes

- Baruch Spinoza

- Gottfried Leibniz

Empiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge which opposes other theories of knowledge, such as rationalism, idealism and historicism. Empiricism asserts that knowledge comes (only or primarily) via sensory experience as opposed to rationalism, which asserts that knowledge comes (also) from pure thinking. Both empiricism and rationalism are individualist theories of knowledge, whereas historicism is a social epistemology. While historicism also acknowledges the role of experience, it differs from empiricism by assuming that sensory data cannot be understood without considering the historical and cultural circumstances in which observations are made. Empiricism should not be mixed up with empirical research because different epistemologies should be considered competing views on how best to do studies, and there is near consensus among researchers that studies should be empirical. Today empiricism should therefore be understood as one among competing ideals of getting knowledge or how to do studies. As such empiricism is first and foremost characterized by the ideal to let observational data "speak for themselves", while the competing views are opposed to this ideal. The term empiricism should thus not just be understood in relation to how this term has been used in the history of philosophy. It should also be constructed in a way which makes it possible to distinguish empiricism among other epistemological positions in contemporary science and scholarship. In other words: Empiricism as a concept has to be constructed along with other concepts, which together make it possible to make important discriminations between different ideals underlying contemporary science.

Empiricism is one of several competing views that predominate in the study of human knowledge, known as epistemology. Empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence, especially sensory perception, in the formation of ideas, over the notion of innate ideas or tradition[5] in contrast to, for example, rationalism which relies upon reason and can incorporate innate knowledge.

Empiricists

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of such topics as politics, liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority: what they are, why (or even if) they are needed, what, if anything, makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect and why, what form it should take and why, what the law is, and what duties citizens owe to a legitimate government, if any, and when it may be legitimately overthrown—if ever. In a vernacular sense, the term "political philosophy" often refers to a general view, or specific ethic, political belief or attitude, about politics that does not necessarily belong to the technical discipline of philosophy.[6]

By country

- United Kingdom

- France

- Italy

- Germany

Idealism

Idealism refers to the group of philosophies which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally a construct of the mind or otherwise immaterial. Epistemologically, idealism manifests as a skepticism about the possibility of knowing any mind-independent thing. In a sociological sense, idealism emphasizes how human ideas—especially beliefs and values—shape society.[7] As an ontological doctrine, idealism goes further, asserting that all entities are composed of mind or spirit.[8] Idealism thus rejects physicalist and dualist theories that fail to ascribe priority to the mind. An extreme version of this idealism can exist in the philosophical notion of solipsism.

Idealist philosophers

Existentialism

Existentialism is generally considered to be the philosophical and cultural movement which holds that the starting point of philosophical thinking must be the individual and the experiences of the individual. Building on that, existentialists hold that moral thinking and scientific thinking together do not suffice to understand human existence, and, therefore, a further set of categories, governed by the norm of authenticity, is necessary to understand human existence.[9][10][11]

Existential philosophers

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the study of the structure of experience. It is a broad philosophical movement founded in the early years of the 20th century by Edmund Husserl, expanded upon by a circle of his followers at the universities of Göttingen and Munich in Germany. The philosophy then spread to France, the United States, and elsewhere, often in contexts far removed from Husserl's early work.[12]

Phenomenological philosophers

Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition centered on the linking of practice and theory. It describes a process where theory is extracted from practice, and applied back to practice to form what is called intelligent practice. Important positions characteristic of pragmatism include instrumentalism, radical empiricism, verificationism, conceptual relativity, and fallibilism. There is general consensus among pragmatists that philosophy should take the methods and insights of modern science into account.[13] Charles Sanders Peirce (and his pragmatic maxim) deserves most of the credit for pragmatism,[14] along with later twentieth century contributors William James and John Dewey.[13]

Pragmatist philosophers

Analytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy came to dominate English-speaking countries in the 20th century. In the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand, the overwhelming majority of university philosophy departments identify themselves as "analytic" departments.[15] The term generally refers to a broad philosophical tradition[16][17] characterized by an emphasis on clarity and argument (often achieved via modern formal logic and analysis of language) and a respect for the natural sciences.[18][19][20]

Analytic philosophers

- Rudolf Carnap

- Gottlob Frege

- George Edward Moore

- Bertrand Russell

- Moritz Schlick

- Ludwig Wittgenstein

Modern Asian philosophy

Various philosophical movements in Asia arose in the modern period including:

- New Confucianism

- Maoism

- Buddhist modernism

- Kyoto school

- Neo-Vedanta

Notes

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- Brian Leiter (ed.), The Future for Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 44 n. 2.

- "Niccolo Machiavelli | Biography, Books, Philosophy, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- Hampton, Jean (1997). Political philosophy. p. xiii. ISBN 9780813308586. Charles Blattberg, who defines politics as "responding to conflict with dialogue," suggests that political philosophies offer philosophical accounts of that dialogue. See his "Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies". SSRN 1755117. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) in Patriotic Elaborations: Essays in Practical Philosophy, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009. - Macionis, John J. (2012). Sociology 14th Edition. Boston: Pearson. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-205-11671-3.

- Daniel Sommer Robinson, "Idealism", Encyclopædia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/281802/idealism

- Mullarkey, John, and Beth Lord (eds.). The Continuum Companion to Continental Philosophy. London, 2009, p. 309

- Stewart, Jon. Kierkegaard and Existentialism. Farnham, England, 2010, p. ix

- Crowell, Steven (October 2010). "Existentialism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

- Zahavi, Dan (2003), Husserl's Phenomenology, Stanford: Stanford University Press

- Biesta, G.J.J. & Burbules, N. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Susan Haack; Robert Edwin Lane (11 April 2006). Pragmatism, old & new: selected writings. Prometheus Books. pp. 18–67. ISBN 978-1-59102-359-3. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Without exception, the best philosophy departments in the United States are dominated by analytic philosophy, and among the leading philosophers in the United States, all but a tiny handful would be classified as analytic philosophers. Practitioners of types of philosophizing that are not in the analytic tradition—such as phenomenology, classical pragmatism, existentialism, or Marxism—feel it necessary to define their position in relation to analytic philosophy." John Searle (2003) Contemporary Philosophy in the United States in N. Bunnin and E.P. Tsui-James (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd ed., (Blackwell, 2003), p. 1.

- See, e.g., Avrum Stroll, Twentieth-Century Analytic Philosophy (Columbia University Press, 2000), p. 5: "[I]t is difficult to give a precise definition of 'analytic philosophy' since it is not so much a specific doctrine as a loose concatenation of approaches to problems." Also, see ibid., p. 7: "I think Sluga is right in saying 'it may be hopeless to try to determine the essence of analytic philosophy.' Nearly every proposed definition has been challenged by some scholar. [...] [W]e are dealing with a family resemblance concept."

- See Hans-Johann Glock, What Is Analytic Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 205: "The answer to the title question, then, is that analytic philosophy is a tradition held together both by ties of mutual influence and by family resemblances."

- Brian Leiter (2006) webpage “Analytic” and “Continental” Philosophy. Quote on the definition: "'Analytic' philosophy today names a style of doing philosophy, not a philosophical program or a set of substantive views. Analytic philosophers, crudely speaking, aim for argumentative clarity and precision; draw freely on the tools of logic; and often identify, professionally and intellectually, more closely with the sciences and mathematics, than with the humanities."

- H. Glock, "Was Wittgenstein an Analytic Philosopher?", Metaphilosophy, 35:4 (2004), pp. 419–444.

- Colin McGinn, The Making of a Philosopher: My Journey through Twentieth-Century Philosophy (HarperCollins, 2002), p. xi.: "analytical philosophy [is] too narrow a label, since [it] is not generally a matter of taking a word or concept and analyzing it (whatever exactly that might be). [...] This tradition emphasizes clarity, rigor, argument, theory, truth. It is not a tradition that aims primarily for inspiration or consolation or ideology. Nor is it particularly concerned with 'philosophy of life,' though parts of it are. This kind of philosophy is more like science than religion, more like mathematics than poetry – though it is neither science nor mathematics."

External links

- Modern philosophy at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project