Rugby World Cup

The Rugby World Cup is a men's rugby union tournament contested every four years between the top international teams. The tournament was first held in 1987, when the tournament was co-hosted by New Zealand and Australia.

| Current season or competition: | |

The Webb Ellis Cup is awarded to the winner of the men's Rugby World Cup | |

| Sport | Rugby union |

|---|---|

| Instituted | 1987 |

| Number of teams | 20 |

| Regions | Worldwide (World Rugby) |

| Holders | |

| Most titles | |

| Website | www |

The opening ceremony of the 2019 tournament | |

| Tournaments | |

|---|---|

The winners are awarded the Webb Ellis Cup, named after William Webb Ellis, the Rugby School pupil who, according to a popular legend, invented rugby by picking up the ball during a football game. Four countries have won the trophy; New Zealand and South Africa three times, Australia twice, and England once. South Africa are the current champions, having defeated England in the final of the 2019 tournament in Japan.

The tournament is administered by World Rugby, the sport's international governing body. Sixteen teams were invited to participate in the inaugural tournament in 1987, however since 1999 twenty teams have taken part. Japan hosted the 2019 Rugby World Cup and France will host the next in 2023.

On 21 August 2019, World Rugby announced that gender designations would be removed from the titles of the men's and women's World Cups. Accordingly, all future World Cups for men and women will officially bear the "Rugby World Cup" name. The first tournament to be affected by the new policy will be the next women's tournament to be held in New Zealand in 2021, which will officially be titled as "Rugby World Cup 2021".[1]

Format

Qualification

Qualifying tournaments were introduced for the second tournament, where eight of the sixteen places were contested in a twenty-four-nation tournament.[2] The inaugural World Cup in 1987, did not involve any qualifying process; instead, the 16 places were automatically filled by seven eligible International Rugby Football Board (IRFB, now World Rugby) member nations, and the rest by invitation.[3]

In 2003 and 2007, the qualifying format allowed for eight of the twenty available positions to be filled by automatic qualification, as the eight quarter-finalists of the previous tournament enter its successor. The remaining twelve positions were filled by continental qualifying tournaments.[4] Positions were filled by three teams from the Americas, one from Asia, one from Africa, three from Europe and two from Oceania.[4] Another two places were allocated for repechage. The first repechage place was determined by a match between the runners-up from the Africa and Europe qualifying tournaments, with that winner then playing the Americas runner-up to determine the place.[5] The second repechage position was determined between the runners-up from the Asia and Oceania qualifiers.[5]

The current format allows for 12 of the 20 available positions to be filled by automatic qualification, as the teams who finish third or better in the group (pool) stages of the previous tournament enter its successor (where they will be seeded).[6][7] The qualification system for the remaining eight places is region-based, with a total eight teams allocated for Europe, five for Oceania, three for the Americas, two for Africa, and one for Asia. The last place is determined by an intercontinental play-off.[8]

Tournament

The 2015 tournament involved twenty nations competing over six weeks.[7][9] There were two stages, a pool and a knockout. Nations were divided into four pools, A through to D, of five nations each.[9][10] The teams were seeded before the start of the tournament, with the seedings taken from the World Rankings in December 2012. The four highest-ranked teams were drawn into pools A to D. The next four highest-ranked teams were then drawn into pools A to D, followed by the next four. The remaining positions in each pool were filled by the qualifiers.[7][11]

Nations play four pool games, playing their respective pool members once each.[10] A bonus points system is used during pool play. If two or more teams are level on points, a system of criteria is used to determine the higher ranked; the sixth and final criterion decides the higher rank through the official World Rankings.[10]

The winner and runner-up of each pool enter the knockout stage. The knockout stage consists of quarter- and semi-finals, and then the final. The winner of each pool is placed against a runner-up of a different pool in a quarter-final. The winner of each quarter-final goes on to the semi-finals, and the respective winners proceed to the final. Losers of the semi-finals contest for third place, called the 'Bronze Final'. If a match in the knockout stages ends in a draw, the winner is determined through extra time. If that fails, the match goes into sudden death and the next team to score any points is the winner. As a last resort, a kicking competition is used.[10]

History

Prior to the Rugby World Cup, there was no truly global rugby union competition, but there were a number of other tournaments. One of the oldest is the annual Six Nations Championship, which started in 1883 as the Home Nations Championship, a tournament between England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. It expanded to the Five Nations in 1910, when France joined the tournament. France did not participate from 1931 to 1939, during which period it reverted to a Home Nations championship. In 2000, Italy joined the competition, which became the Six Nations.[12]

Rugby union was also played at the Summer Olympic Games, first appearing at the 1900 Paris games and subsequently at London in 1908, Antwerp in 1920, and Paris again in 1924. France won the first gold medal, then Australasia, with the last two being won by the United States. However rugby union ceased to be on Olympic program after 1924.[13][14][lower-alpha 1]

The idea of a Rugby World Cup had been suggested on numerous occasions going back to the 1950s, but met with opposition from most unions in the IRFB.[15] The idea resurfaced several times in the early 1980s, with the Australian Rugby Union (ARU; now known as Rugby Australia) in 1983, and the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU; now known as New Zealand Rugby) in 1984 independently proposing the establishment of a world cup.[16] A proposal was again put to the IRFB in 1985 and this time passed 10–6. The delegates from Australia, France, New Zealand and South Africa all voted for the proposal, and the delegates from Ireland and Scotland against; the English and Welsh delegates were split, with one from each country for and one against.[15][16]

The inaugural tournament, jointly hosted by Australia and New Zealand, was held in May and June 1987, with sixteen nations taking part.[17] New Zealand became the first-ever champions, defeating France 29–9 in the final.[18] The subsequent 1991 tournament was hosted by England, with matches played throughout Britain, Ireland and France. This tournament saw the introduction of a qualifying tournament; eight places were allocated to the quarter-finalists from 1987, and the remaining eight decided by a thirty-five nation qualifying tournament.[2] Australia won the second tournament, defeating England 12–6 in the final.[19]

In 1992, eight years after their last official series,[lower-alpha 2] South Africa hosted New Zealand in a one-off test match. The resumption of international rugby in South Africa came after the dismantling of the apartheid system, and was only done with permission of the African National Congress.[20][21] With their return to test rugby, South Africa were selected to host the 1995 Rugby World Cup.[22] After upsetting Australia in the opening match, South Africa continued to advance through the tournament until they met New Zealand in the final.[23][24] After a tense final that went into extra time, South Africa emerged 15–12 winners,[25] with then President Nelson Mandela, wearing a Springbok jersey,[24] presenting the trophy to South Africa's captain, Francois Pienaar.[26]

The tournament in 1999 was hosted by Wales with matches also being held throughout the rest of the United Kingdom, Ireland and France. The tournament included a repechage system,[27] alongside specific regional qualifying places,[28] and an increase from sixteen to twenty participating nations.[29] Australia claimed their second title, defeating France in the final.[30]

The 2003 event was hosted by Australia, although it was originally intended to be held jointly with New Zealand. England emerged as champions defeating Australia in extra time. England's win was unique in that it broke the southern hemisphere's dominance in the event. Such was the celebration of England's victory that an estimated 750,000 people gathered in central London to greet the team, making the day the largest sporting celebration of its kind ever in the United Kingdom.[31]

The 2007 competition was hosted by France, with matches also being held in Wales and Scotland. South Africa claimed their second title by defeating defending champions England 15–6. The 2011 tournament was awarded to New Zealand in November 2005, ahead of bids from Japan and South Africa. The All Blacks reclaimed their place atop the rugby world with a narrow 8–7 win over France in the 2011 final.

In the 2015 edition of tournament, hosted by England, New Zealand once again won the final, this time against established rivals, Australia. In doing so, they became the first team in World Cup history to win three titles, as well as the first to successfully defend a title. It was also New Zealand's first title victory on foreign soil.

The 2019 World Cup, hosted by Japan, saw South Africa claim their third trophy to match New Zealand for the most Rugby World Cup titles. South Africa defeated England 32–12 in the final.

Trophy

The Webb Ellis Cup is the prize presented to winners of the Rugby World Cup, named after William Webb Ellis. The trophy is also referred to simply as the Rugby World Cup. The trophy was chosen in 1987 as an appropriate cup for use in the competition, and was created in 1906 by Garrard's Crown Jewellers.[32][33] The trophy is restored after each game by fellow Royal Warrant holder Thomas Lyte.[34][35] The words 'The International Rugby Football Board' and 'The Webb Ellis Cup' are engraved on the face of the cup. It stands thirty-eight centimetres high and is silver gilded in gold, and supported by two cast scroll handles, one with the head of a satyr, and the other a head of a nymph.[36] In Australia the trophy is colloquially known as "Bill" — a reference to William Webb Ellis.

Selection of hosts

Tournaments are organised by Rugby World Cup Ltd (RWCL), which is itself owned by World Rugby. The selection of host is decided by a vote of World Rugby Council members.[37][38] The voting procedure is managed by a team of independent auditors, and the voting kept secret. The allocation of a tournament to a host nation is now made five or six years prior to the commencement of the event, for example New Zealand were awarded the 2011 event in late 2005.

The tournament has been hosted by multiple nations. For example, the 1987 tournament was co-hosted by Australia and New Zealand. World Rugby requires that the hosts must have a venue with a capacity of at least 60,000 spectators for the final.[39] Host nations sometimes construct or upgrade stadia in preparation for the World Cup, such as Millennium Stadium – purpose built for the 1999 tournament – and Eden Park, upgraded for 2011.[39][40] The first country outside of the traditional rugby nations of SANZAAR or the Six Nations to be awarded the hosting rights was 2019 host Japan. France will host the 2023 tournament.

Tournament growth

Media coverage

Organizers of the Rugby World Cup, as well as the Global Sports Impact, state that the Rugby World Cup is the third largest sporting event in the world, behind only the FIFA World Cup and the Olympics,[41][42] although other sources question whether this is accurate.[43]

Reports emanating from World Rugby and its business partners have frequently touted the tournament's media growth, with cumulative worldwide television audiences of 300 million for the inaugural 1987 tournament, 1.75 billion in 1991, 2.67 billion in 1995, 3 billion in 1999,[44] 3.5 billion in 2003,[45] and 4 billion in 2007.[46] The 4 billion figure was widely dismissed as the global audience for television is estimated to be about 4.2 billion.[47]

However, independent reviews have called into question the methodology of those growth estimates, pointing to factual inconsistencies.[48] The event's supposed drawing power outside of a handful of rugby strongholds was also downplayed significantly, with an estimated 97 percent of the 33 million average audience produced by the 2007 final coming from Australasia, South Africa, the British Isles and France.[49] Other sports have been accused of exaggerating their television reach over the years; such claims are not exclusive to the Rugby World Cup.

While the event's global popularity remains a matter of dispute, high interest in traditional rugby nations is well documented. The 2003 final, between Australia and England, became the most watched rugby union match in the history of Australian television.[50]

Attendance

| Year | Host(s) | Total attendance | Matches | Avg attendance | % change in avg att. |

Stadium capacity | Attendance as % of capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 604,500 | 32 | 20,156 | — | 1,006,350 | 60% | |

| 1991 | 1,007,760 | 32 | 31,493 | +56% | 1,212,800 | 79% | |

| 1995 | 1,100,000 | 32 | 34,375 | +9% | 1,423,850 | 77% | |

| 1999 | 1,750,000 | 41 | 42,683 | +24% | 2,104,500 | 83% | |

| 2003 | 1,837,547 | 48 | 38,282 | –10% | 2,208,529 | 83% | |

| 2007 | 2,263,223 | 48 | 47,150 | +23% | 2,470,660 | 92% | |

| 2011 | 1,477,294 | 48 | 30,777 | –35% | 1,732,000 | 85% | |

| 2015 | 2,477,805 | 48 | 51,621 | +68% | 2,600,741 | 95% | |

| 2019 | 1,698,528 | 45† | 37,745 | –27% | 1,811,866 | 90% | |

| 2023 | To be determined | 48 | To be determined | ||||

†Typhoon Hagibis caused 3 group stage matches to be cancelled. As a result, only 45 of the scheduled 48 matches were played in the 2019 Rugby World Cup.

Revenue

| Source | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate receipts (M £) | -- | -- | 15 | 55 | 81 | 147 | 131 | 250 | -- |

| Broadcasting (M £) | -- | -- | 19 | 44 | 60 | 82 | 93 | 155 | -- |

| Sponsorship (M £) | -- | -- | 8 | 18 | 16 | 28 | 29 | -- | -- |

Notes:

- The host union keeps revenue from gate receipts. World Rugby, through RWCL, receive revenue from sources including broadcasting rights, sponsorship and tournament fees.[51]

Results

Tournaments

| Year | Host(s) | Final | Bronze Final | Number of teams | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winner | Score | Runner-up | 3rd place | Score | 4th place | ||||||

| 1987 | New Zealand |

29–9 | France |

Wales |

22–21 | Australia |

16 | ||||

| 1991 | Australia |

12–6 | England |

New Zealand |

13–6 | Scotland |

16 | ||||

| 1995 | South Africa |

15–12 (aet) |

New Zealand |

France |

19–9 | England |

16 | ||||

| 1999 | Australia |

35–12 | France |

South Africa |

22–18 | New Zealand |

20 | ||||

| 2003 | England |

20–17 (aet) |

Australia |

New Zealand |

40–13 | France |

20 | ||||

| 2007 | South Africa |

15–6 | England |

Argentina |

34–10 | France |

20 | ||||

| 2011 | New Zealand |

8–7 | France |

Australia |

21–18 | Wales |

20 | ||||

| 2015 | New Zealand |

34–17 | Australia |

South Africa |

24–13 | Argentina |

20 | ||||

| 2019 | South Africa |

32–12 | England |

New Zealand |

40–17 | Wales |

20 | ||||

| 2023 | To be determined | To be determined | 20 | ||||||||

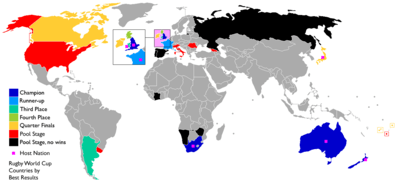

Performance of nations

Twenty-five nations have participated at the Rugby World Cup (excluding qualifying tournaments). The only nations to host and win a tournament are New Zealand (1987 and 2011) and South Africa (1995). The performance of other host nations includes England (1991 final hosts) and Australia (2003 hosts) both finishing runners-up, while France (2007 hosts) finished fourth, and Wales (1999 hosts) and Japan (2019 hosts) reached the quarter-finals. Wales became the first host nation to be eliminated at the pool stages in 1991 while England became the first solo host nation to be eliminated at the pool stages in 2015. Of the twenty-five nations that have participated in at least one tournament, eleven of them have never missed a tournament.[lower-alpha 3]

Team records

| Team | Champions | Runners-up | Third | Fourth | Quarterfinals | Appearances in top 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 (1987, 2011, 2015) | 1 (1995) | 3 (1991, 2003, 2019) | 1 (1999) | 1 (2007) | 9 | |

| 3 (1995, 2007, 2019) | – | 2 (1999, 2015) | – | 2 (2003, 2011) | 7 table footnote 1 | |

| 2 (1991, 1999) | 2 (2003, 2015) | 1 (2011) | 1 (1987) | 3 (1995, 2007, 2019) | 9 | |

| 1 (2003) | 3 (1991, 2007, 2019) | – | 1 (1995) | 3 (1987, 1999, 2011) | 8 | |

| – | 3 (1987, 1999, 2011) | 1 (1995) | 2 (2003, 2007) | 3 (1991, 2015, 2019) | 9 | |

| – | – | 1 (1987) | 2 (2011, 2019) | 3 (1999, 2003, 2015) | 6 | |

| – | – | 1 (2007) | 1 (2015) | 2 (1999, 2011) | 4 | |

| – | – | – | 1 (1991) | 6 (1987, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2015) | 7 | |

| – | – | – | – | 7 (1987, 1991, 1995, 2003, 2011, 2015, 2019) | 7 | |

| – | – | – | – | 2 (1987, 2007) | 2 | |

| – | – | – | – | 2 (1991, 1995) | 2 | |

| – | – | – | – | 1 (1991) | 1 | |

| – | – | – | – | 1 (2019) | 1 | |

1 South Africa was excluded from the first two tournaments due to a sporting boycott during the apartheid era.

Records and statistics

The record for most points overall is held by English player Jonny Wilkinson, who scored 277 during his World Cup career.[52] New Zealand All Black Grant Fox holds the record for most points in one competition, with 126 in 1987;[52] Jason Leonard of England holds the record for most World Cup matches: 22 between 1991 and 2003.[52] All Black Simon Culhane holds the record for most points in a match by one player, 45, as well as the record for most conversions in a match, 20.[53] All Black Marc Ellis holds the record for most tries in a match, six, which he scored against Japan in 1995.[54]

New Zealand All Black Jonah Lomu is the youngest player to appear in a final – aged 20 years and 43 days at the 1995 Final.[55] Lomu (playing in two tournaments) and South African Bryan Habana (playing in three tournaments) share the record for most total World Cup tournament tries, both scoring 15.[54] Lomu (in 1999) and Habana (in 2007) also share the record, along with All Black Julian Savea (in 2015), for most tries in a tournament, with 8 each.[54] South Africa's Jannie de Beer kicked five drop-goals against England in 1999 – an individual record for a single World Cup match.[55] The record for most penalties in a match is 8, held by Australian Matt Burke, Argentinian Gonzalo Quesada, Scotland's Gavin Hastings and France's Thierry Lacroix,[53] with Quesada also holding the record for most penalties in a tournament, with 31.

The most points scored in a game is 145, by the All Blacks against Japan in 1995, while the widest winning margin is 142, held by Australia in a match against Namibia in 2003.[56]

A total of 16 players have been sent off (red carded) in the tournament. Welsh lock Huw Richards was the first, while playing against New Zealand in 1987. No player has been red carded more than once.[53]

See also

- Rugby World Cup (women's)

- Rugby World Cup Sevens – men's and women's tournaments held simultaneously at a single site

- Records and statistics of the Rugby World Cup

- International rugby union team records

- International rugby union player records

References

Printed sources

- Collins, Tony (2008). "'The First Principle of Our Game': The rise and fall of amateurism: 1886–1995". In Ryan, Greg (ed.). The Changing Face of Rugby: The Union Game and Professionalism since 1995. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84718-530-3.

- Davies, Gerald (2004). The History of the Rugby World Cup Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-86074-602-0.

- Farr-Jones, Nick, (2003). Story of the Rugby World Cup, Australian Post Corporation. ISBN 0-642-36811-2.

- Harding, Grant; Williams, David (2000). The Toughest of Them All: New Zealand and South Africa: The Struggle for Rugby Supremacy. Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-029577-1.

- Martin, Gerard John (2005). The Game is not the Same – a History of Professional Rugby in New Zealand (Thesis). Auckland University of Technology.

- Peatey, Lance (2011). In Pursuit of Bill: A Complete History of the Rugby World Cup. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-74257-191-1.

- Phillpots, Kyle (2000). The Professionalisation of Rugby Union (Thesis). University of Warwick.

- Williams, Peter (2002). "Battle Lines on Three Fronts: The RFU and the Lost War Against Professionalism". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 19 (4): 114–136. doi:10.1080/714001793.

Notes

- However an exhibition tournament did take place at the 1936 Games. Rugby was reintroduced to the Olympics in 2016, but as men's and women's rugby sevens (i.e., seven-a-side rugby).[13]

- Against England in 1984.[20]

- Argentina, Australia, England, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Scotland, Wales and Canada are the nations that have never missed a tournament, playing in all nine thus far. South Africa has played in all seven in the post-apartheid era (as of 2019).

Citations

- "World Rugby announces gender neutral naming for Rugby World Cup tournaments" (Press release). World Rugby. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Peatey (2011) p. 59.

- Peatey (2011) p. 34.

- "Doin' it the Hard Way". Rugby News. 38 (9). 2007. p. 26.

- "Doin' it the Hard Way". Rugby News. 38 (9). 2007. p. 27.

- "Rankings to determine RWC pools". BBC News. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "AB boost as World Cup seedings confirmed". stuff.co.nz. NZPA. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Caribbean kick off for RWC 2011 qualifying". irb.com. 3 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "Fixtures". World Rugby. Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Tournament Rules". World Rugby. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "2015 Rugby World Cup seedings take shape". TVNZ. AAP. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012.

- "A brief history of the Six Nations rugby tournament". 6 Nations Rugby. Archived from the original on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- "History of Rugby in the Olympics". World Rugby. 9 November 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Richards, Huw (26 July 2012). "Rugby and the Olympics". ESPN. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "The History of RWC". worldcupweb.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- Collins (2008), p. 13.

- Peatey (2011) p. 31.

- Peatey (2011) p. 42.

- Peatey (2011) p. 77.

- Harding (2000), p. 137

- Peatey (2011) p. 78.

- Peatey (2011) p. 82.

- Peatey (2011) p. 87.

- Harding (2000), pp. 159–160

- Peatey (2011) p. 99.

- Harding (2000), p. 168

- "Rugby World Cup history: The Wizards from Oz in 1999". Sky Sports. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "1999 World Cup Qualifiers". CNN Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 3 May 2004. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Madden, Patrick (4 September 2015). "RWC #15: Ireland suffer play-off misery against Argentina". The Irish Times. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Kitson, Robert (8 November 1999). "Wallaby siege mentality secures Holy Grail". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "England honours World Cup stars". bbc.co.uk. 9 December 2003. Retrieved 3 May 2006.

- "Second World Cup exists, Snedden confirms". New Zealand Herald. 18 August 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Quinn, Keith (30 August 2011). "Keith Quinn: Back-history of RWC – part three". TVNZ. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014.

- "Friday Boss: Kevin Baker of silversmiths Thomas Lyte". BBC News.

- "Thomas Lyte". royalwarrant.org.

- "The History of the Webb Ellis Cup". Sky Sport New Zealand. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Official Website of the Rugby World Cup". rugbyworldcup.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- "England awarded 2015 Rugby World Cup". ABC News Australia. AFP. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "New Zealand came close to losing Rugby World Cup 2011". Rugby Week. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Millennium Stadium, Cardiff". Virtual Tourist. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- "Rugby World Cup 2015 Official Hospitality". RWC Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Olympics and World Cup are the biggest, but what comes next?". BBC Sport. 4 December 2014.

- "Rugby World Cup: Logic debunks outrageous numbers game". New Zealand Herald. 23 October 2011. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Rugby World Cup 2003". sevencorporate.com.au. Archived from the original on 15 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- "Visa International Renews Rugby World Cup Partnership". corporate.visa.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- "Potential Impact of the Rugby World Cup on a Host Nation" (PDF). Deloitte & Touche. 2008. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- "Digital Divide: Global Household Penetration Rates for Technology". VRWorld. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Nippert, Matt (2 May 2010). "Filling the Cup – cost $500m and climbing". New Zealand Herald. APN New Zealand. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Burgess, Michael (23 October 2011). "Logic debunks outrageous numbers game". New Zealand Herald. APN New Zealand. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Derriman, Phillip (1 July 2006). "Rivals must assess impact of Cup fever". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax. Retrieved 1 July 2006.

- International Rugby Board Year in Review 2012. International Rugby Board. p. 62. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Peatey (2011) p. 243.

- "All Time RWC Statistics". International Rugby Board. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Peatey (2011) p. 244.

- Peatey (2011) p. 245.

- Peatey (2011) p. 242.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rugby World Cup. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Rugby World Cup – official site

- World Rugby

.jpg)